Barsoom: Difference between revisions

dab Soyuz |

hello bias |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{npov}} |

|||

[[File:Princess of Mars large.jpg|thumb|right|''A Princess of Mars'' by [[Edgar Rice Burroughs]], [[A. C. McClurg|McClurg]], 1917]] |

[[File:Princess of Mars large.jpg|thumb|right|''A Princess of Mars'' by [[Edgar Rice Burroughs]], [[A. C. McClurg|McClurg]], 1917]] |

||

Revision as of 00:28, 12 April 2012

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Barsoom is a fictional representation of the planet Mars created by American pulp fiction author Edgar Rice Burroughs. The first Barsoom tale was serialized as Under the Moons of Mars in 1912, and published as a novel as A Princess of Mars in 1917. Ten sequels followed over the next three decades, further extending his vision of Barsoom and adding other characters.

The world of Barsoom is a romantic vision of a dying Mars, based on now-outdated scientific ideas made popular by Astronomer Percival Lowell in the early 20th century. While depicting many outlandish inventions, and advanced technology, it is a savage world of honor, noble sacrifice, and constant struggle, where martial prowess is paramount, and where many races fight over dwindling resources. It is filled with lost cities, heroic adventures and forgotten ancient secrets.

The series has inspired a number of well known science fiction writers in the 20th century, and also key scientists involved in both space exploration and the search for extraterrestrial life. It has informed and been adapted by many writers, in novels, short stories, comics, television and film.

Series

Burroughs began writing the Barsoom books in the second half of 1911, and produced one volume a year between 1911 and 1914; seven more were produced between 1921 and 1941.[1] The first Barsoom tale was serialized in The All-Story magazine as Under the Moons of Mars (1912), and then published in hardcover as the complete novel A Princess of Mars (1917).[2][3] The final Barsoom tale was a novella, Skeleton Men of Jupiter, published in Amazing Stories in February 1943.[4]

| Order | Title | Published as serial | Published as novel | Fictional narrator | Year in novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A Princess of Mars | February–July 1912, All-Story | October 1917, McClurg | John Carter | 1866–1876 |

| 2 | The Gods of Mars | January–May 1913, All-Story | September 1918, McClurg | John Carter | 1886 |

| 3 | The Warlord of Mars | December 1913-March 1914, All-Story | September 1919, McClurg | John Carter | 1887–1888 |

| 4 | Thuvia, Maid of Mars | April 1916, All-Story Weekly | October 1920, McClurg | third person | 1888~1898 |

| 5 | The Chessmen of Mars | February–March 1922, Argosy All-Story Weekly | November 1922, McClurg | third person | 1898~1917 |

| 6 | The Master Mind of Mars | July 15, 1927, Amazing Stories Annual | March 1928, McClurg | Ulysses Paxton | 1917 |

| 7 | A Fighting Man of Mars | April–September 1930, Blue Book | May 1931, Metropolitan | Tan Hadron | 1928 |

| 8 | Swords of Mars | November 1934-April 1935, Blue Book | February 1936, Burroughs | John Carter | 1928~1934 |

| 9 | Synthetic Men of Mars | January–February 1939, Argosy Weekly | March 1940, Burroughs | Vor Daj | 1934~1938 |

| 10 | Llana of Gathol | March–October 1941, Amazing Stories | March 1948, Burroughs | John Carter | 1938~1940 |

| 11 | John Carter of Mars: John Carter and the Giant of Mars (by John Coleman Burroughs) |

January 1941, Amazing Stories | July 1964, Canaveral | third person | 1940 |

| John Carter of Mars: Skeleton Men of Jupiter | February 1943, Amazing Stories | John Carter | 1941–1942 |

Etymology

Burroughs frequently made up words from the languages spoken by the peoples in his novels, and used these extensively in the narrative. In Thuvia, Maid of Mars he included a glossary of Barsoomian words used in the first four novels. The word "Barsoom", the native Martian word for Mars, is composed of the Martian name for planet, "soom", and the Martian word for eight, "bar". This assumes that Mars is the eighth body in the inner solar system, though to reach this figure it is necessary to count the Sun and the satellites of both the Earth and Mars itself even though they are not planets.[5]

Character focus

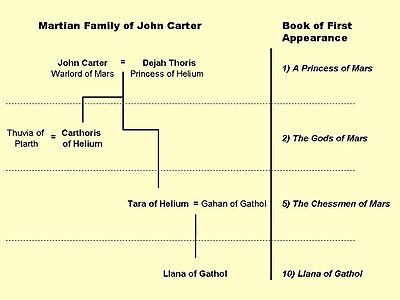

A Princess of Mars, the first novel in the Barsoom series, is a stand-alone. It connects, however, with the two novels that followed, The Gods of Mars and The Warlord of Mars, to form a trilogy (although there is a ten-year gap between the first and second novels). The trilogy focuses on Earthman John Carter and Martian princess Dejah Thoris, with Green Martian Tars Tarkas making frequent appearances. John Carter's and Dejah Thoris's son Carthoris is also introduced as a minor character in The Gods of Mars, as is Thuvia.[6]

Three other books focus on their descendants: Carthoris, in Thuvia, Maid of Mars, his sister, Tara of Helium, in The Chessmen of Mars, and Tara's daughter, Llana of Gathol, in Llana of Gathol.

Ulysses Paxton, another Earth man transported to Mars, is the focus of The Master Mind of Mars, and the rest of the books focus on John Carter's later adventures (Swords of Mars and John Carter of Mars), or native Martian characters (A Fighting Man of Mars and Synthetic Men of Mars).[7]

Form

The majority of the tales are novels, but two of the books in the series of eleven are collections of shorter works: Llana of Gathol has four linked novelettes, originally published in Amazing Stories during 1941,[8] and John Carter of Mars is composed of two novellas.

Most of the tales are first-person narratives. John Carter narrates A Princess of Mars, The Gods of Mars, The Warlord of Mars, Swords of Mars, the four novellas in Llana of Gathol and "Skeleton Men of Jupiter" in John Carter of Mars. Ulysses Paxton narrates one, The Master Mind of Mars. Martian guardsman Vor Daj narrates Synthetic Men of Mars and Martian navy officer Tan Hadron narrates A Fighting Man of Mars. Two other novels, Thuvia, Maid of Mars and The Chessmen of Mars, are written in the third person, as is "John Carter and the Giant of Mars" in John Carter of Mars.

Introductions

Beginning with A Princess of Mars, Burroughs established a practice which continued in the four sequels: introducing the novel as though it were a factual account passed on to him personally. He describes John Carter to be an avuncular figure known to his family for years, who gave him the manuscript during an earlier visit, with instructions not to publish it for twenty-one years.[5] The same device appears in several sequels: The Gods of Mars, The Chessmen of Mars, Swords of Mars, and Llana of Gathol.

Authorship

All of the Barsoom tales were published under the name of Edgar Rice Burroughs (except Under the Moons of Mars, the first publication of A Princess of Mars, which was published under the pseudonym "Norman Bean." Burroughs had actually typed "Normal Bean" (meaning not crazy in the head) on his submitted manuscript, but his publisher's typesetter thought it a typo and changed it to "Norman." The first novella in John Carter of Mars, "John Carter and the Giant of Mars", is thought to have been penned by Burroughs's son John "Jack" Coleman Burroughs, although allegedly revised by his father. It was recognized by fans, upon publication, as unlikely of being Burroughs' work, as the writing is of a juvenile quality compared to that of Burroughs' other stories.[4]

Genre

The stories are science fantasy, belonging to the subgenre planetary romance, which has strong elements of both science fiction and fantasy.[9] Planetary romance stories are similar to sword and sorcery tales, but include scientific aspects.[10] They mostly take place on the surface of an alien world, frequently include sword fighting, monsters, supernatural elements such as telepathic abilities, and civilizations similar to Earth in pre-technological eras, particularly with the inclusion of dynastic or religious social structures. Spacecraft may appear, but are not central to the story.[9]

The stories also share a number of elements with westerns in that they feature desert landscapes, women taken captive and a final confrontation with the antagonist.[11]

Burroughs' Barsoom stories are considered seminal planetary romances. While examples existed prior to the publication of his works, they are the key influence on the many works of this type that followed.[9] His style of planetary romance has ceased to be written and published in the mainstream, though his books remain in print.[12]

Plot

Like most of Burroughs' fiction, the novels in the series are mostly travelogues, feature copious action of a violent nature, and often have plots involving civilized heroes being captured by uncivilized cultures and being forced to adapt to the cruel nature of their captors to survive.[13]

While there is variation, most of the Barsoom novels follow a familiar plot structure. A hero is forced to journey to a far-off location in search of a woman he is either in love with or believes himself to be in love with. The woman has been kidnapped by an odious but powerful man, who both desires her and values her for his own political ends.[14] Female characters are frequently threatened with sexual assault;[15] Dejah Thoris (on numerous occasions), Thuvia and Tara of Helium are all subjected to this threat. Tara notably is pursued by a headless body being remotely controlled by telepathy by a Kaldane in The Chessmen of Mars.[7][16]

The hero is awkward with women and will tend to misinterpret their interest in him due to his low confidence or familiarity with the ways of women. Female characters are likely to be virtuous and fight off amorous advances and other dangers until able to connect with the hero.[14] The hero is often forced to adopt a disguise and is not recognized by the heroine.

He will have to fight both strange races and hideous creatures to claim her love. Along the way the hero will encounter kings or other powerful figures who rule over a severely repressed population, ripe for rebellion. He will be instrumental in deposing the ruler, usually with the assistance of a fresh-faced member of the same population, whom the hero will have encountered when both are in some kind of slavery or imprisonment.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Typically the novels include descriptions of aspects of the Martian world such as the architecture, and the presence of desolate landscapes punctuated by abandoned cities — whose histories are often elaborated upon, technological achievements, advanced medicine, cultural elements such as superstitious religious practices and eating habits, breeding practices and methods of population control.[17]

Many lost cities and civilizations and journeys into forgotten underworlds appear across the series, and the environment beyond the cities is populated by a variety of ferocious beasts, many roughly equivalent with Earth creatures and most with multiple sets of limbs. There are numerous examples of striking coincidences and deus ex machina events that are usually to the benefit of the protagonists; perhaps the most striking example is an invisible flying ship in A Fighting Man of Mars which is lost, only to be bumped into by accident some time later, just when needed to escape death.

Mad scientists also appear, Ras Thavas from The Master Mind of Mars and Synthetic Men of Mars being the principal example, although another plays a prominent role in A Fighting Man of Mars.[7] Incidences of the use of superstition by religious cults to control and manipulate others are also common.[18]

A Princess of Mars was possibly the first fiction of the 20th century to feature a constructed language; although Barsoomian was not particularly developed, it did add verisimilitude to the narrative.

Villains

The majority of the villains in the Barsoom series are inplacably evil, and often their appearance matches this. Typically they are rulers or despots of major empires, or little known hidden fiefdoms. They are usually hated by their subjects and possess a voracious sexual appetite, usually directed towards the heroine. The pattern is established by green martian Jeddak, Tal Hajus, in the first novel, A Princess of Mars, hated even by the bloodthirsty green martians. Further examples include the yellow martian Salensus Oll in The Warlord of Mars, Nutus of Dusar in Thuvia, Maid of Mars and Ul Vas, Jeddak of the Tarids in Swords of Mars.[19]

Appeal

The popularity of the Barsoom novels may lie in their reflection of the classic 'rags to riches' tale in a fantastic setting, which may resonate with readers who feel undervalued, and whose abilities are unrecognized. The heroes are men of talent and ability whose circumstances have so far failed to give them the opportunity to reach their proper potential. The epic scale adventures of the novels allow their inner selves to manifest, and reward them with love, companionship, freedom and success. These are action heroes who are noble, fearless and never doubt themselves in the face of adversity. They are not skilled in their dealings with women, but are chivalrous and their noble qualities and fearlessness make them attractive to the heroines. The narratives also set a rapid pace, and offer a considerable sense of escapism. They are mostly read by men, but there are female fans as well.[20]

Principal characters

Earthmen

- John Carter: Captain John Carter is an Earthman, who originated in Virginia. He fought in the American Civil war on the Confederate side.[21] After the war he moved to the southwest US to work as a prospector. In 1866 he and his prospector partner strike it rich, but the partner is killed by American Indians and Carter takes refuge in a cave where he is overcome by smoke produced by an American Indian woman and wakes up on Mars. He effectively disappeared for ten years [while on Mars], and was believed dead, but re-emerged in New York in 1876, settling on the Hudson. He appeared to die in 1886, leaving instructions for Burroughs, who refers to him as an 'uncle', to entomb him in a crypt, and leaving Burroughs with the manuscript of A Princess of Mars with instructions not to publish it for another 21 years.[22] He has no memory before the age of 30 and seems never to age. He is adept with command, horsemanship, swords and all weapons. He is 6'2" tall, with black hair and steel gray eyes.[21] He is honorable, courageous and eternally optimistic, even in the face of certain death.[23] He is transported to the planet Mars by a form of astral projection. There, he encounters both formidable alien creatures and various warring Martian races, wins the hand of martian princess Dejah Thoris, and rises to the position of Warlord of Mars. Protagonist of the first three novels. Carter also headlines the eighth, tenth and eleventh books, and is a major secondary character in the fourth and ninth novels.

- Ulysses Paxton: The central character in The Master Mind of Mars. Paxton is a soldier in the First World War who is transported to Barsoom after he is mortally wounded, and becomes the assistant of scientist Ras Thavas.

Martians

- Dejah Thoris: A Martian Princess of Helium, who is courageous, tough and always holds her resolve, despite being frequently placed in both mortal danger and the threat of being dishonored by the lustful designs of villains. The daughter of Mors Kajak, jed of Lesser Helium and granddaughter of Tardos Mors, jeddak of Helium, she is highly aristocratic and fiercely proud of her heritage.[24] She is introduced early in the first Barsoom novel, A Princess of Mars, and is the love interest of John Carter.[25] She is a central character in the first three novels, and her capture by various enemies, and subsequent pursuit by John Carter, is a constant motivating force in these tales. She is a minor character in The Chessmen of Mars and John Carter of Mars.

- Tars Tarkas: A fierce Green Martian warrior who is unusual among his savage race for his ability to love, and is therefore much affected by the loss of his lover while he is away on a raid. He befriends John Carter and fights many battles at his side. Carter helps him become Jeddak of his tribe and negotiates an alliance between them and the city-state of Helium, which results in the destruction of their enemies, the city of Zodanga, at the end of A Princess of Mars.[22] While John Carter is able to befriend him, and he shows some civilized noble qualities, Tars Tarkas remains unable to understand art or much improve his grasp of technology and still takes pleasure in cruelty and violence.[26]

- Thuvia of Ptarth: A Princess of Ptarth, who first appears in The Gods of Mars, as a slave girl, rescued by John Carter from the nefarious Therns. She is later imprisoned with Carter's wife Dejah Thoris, in a prison which can only be opened once per year and remains by her side until the conclusion of The Warlord of Mars.[27] Like many of Burroughs' Martian heroines, she is tough, courageous, and proud, and strongly identifies with her aristocratic position in Martian society. Also typically, she is abducted by evildoers who wish to use her for political gain in Thuvia, Maid of Mars, her rescue providing primary motivation for the plot of that novel.[28] She is a central character in Thuvia, Maid of Mars and love interest of John Carter and Dejah Thoris' son Carthoris.[27]

- Ras Thavas: A mad scientist who develops both brain transplant techniques and a form of cloning, a principal character in both The Master Mind of Mars and Synthetic Men of Mars.

- Tan Hadron: A young Red Martian navy officer, who is the central character of A Fighting Man of Mars.

- Vor Daj: A soldier in John Carter's guard. Principal character in Synthetic Men of Mars, who spends much of the novel with his brain transplanted into a hideous but powerful synthetic body.

- Gahan of Gathol: A prince of Gathol; love interest for Tara of Helium and father of Llana of Gathol; a principal character in The Chessmen of Mars.

Martian descendants of John Carter and Dejah Thoris

- Carthoris: Son of John Carter and Dejah Thoris who inherits his father's superior strength and ability with a sword. A minor character in The Gods of Mars. A principal character in Thuvia, Maid of Mars and love interest of Thuvia.[29]

- Tara of Helium: Impetuous daughter of John Carter and Dejah Thoris, who runs away and gets involved in various perilous situations as a principal character in The Chessmen of Mars. Love interest of Gahan of Gathol and mother of Llana of Gathol.[16]

- Llana of Gathol: Granddaughter of John Carter and Dejah Thoris and daughter of Tara of Helium and Gahan of Gathol; a principal character in the stories collected in Llana of Gathol.

Environment

While Burroughs' Barsoom tales never aspired to being anything other than exciting escapism, his vision of Mars was loosely inspired by astronomical speculation of the time, especially that of Percival Lowell, that saw the planet as a formerly Earthlike world now becoming less hospitable to life due to its advanced age.[30] Living on an aging planet, with dwindling resources, the inhabitants of Barsoom have become hardened and warlike, fighting one another to survive.[31] Once a wet world with continents and oceans, Barsoom's seas gradually dried up, leaving it a dry planet of highlands interspersed with moss covered dead sea bottoms. Abandoned cities line the former coast lands. The last remnants of the former bodies of water are the Great Toonolian Marshes and the antarctic Lost Sea of Korus.

Barsoomians distribute scarce water supplies via a worldwide system of canals, controlled by quarreling city-states which have grown up at the junctures of the canals. The idea of Martian "canals" stems from telescopic observations by 19th century astronomers who, beginning with Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877, believed they saw networks of lines on the planet. Schiaparelli called them canali ("grooves" in Italian is scanalature, whilst canale is, in fact, channel and/or canal, depending on the context) which was mistranslated in English as "canals". During the time Burroughs wrote his first Barsoom stories, the theory was put forward by a number of prominent scientists, notably Lowell, that these were huge engineering works constructed by an intelligent race. This caught the imagination of the public, resulting in a fascination with Mars which inspired much science fiction. The thinning Martian atmosphere is artificially replenished from an "atmosphere plant" on whose smooth functioning all life on the planet is dependent.[32]

The Martian year comprises 687 Martian days, each of which is 24 hours and 37 minutes long. (Burroughs presumably derived this from the figures published by Lowell, but erroneously substituted the number of 24-hour Earth days in the Martian year, rather than the number of 24.6-hour Martian days, which is only 669.) The days are hot and the nights are cold, and there appears to be little variation in climate across the planet, except at the poles.[33]

Burroughs explained his ideas about the Martian environment in an article "A Dispatch on Mars" published in the London Daily Express in 1926. He assumed that Mars was formerly identical to the Earth; therefore a similar evolutionary development of fauna would have taken place. He referenced winds, snows and marshes which had supposedly been observed by astronomers, as evidence of an atmosphere, and that the wastes of the planet had been irrigated (probably referencing Lowell's canals), which suggested that an advanced civilization existed on the planet.

Peoples and culture

All Barsoomian races resemble Homo sapiens in most respects, except for being oviparous[34] and having lifespans in excess of 1,000 years unless killed through violent means.[2] The traditional Martian lifespan of 1,000 is based on the customary pilgrimage down the River Iss, which is taken by virtually all Martians by that age, or those who feel tired of their long lives and expect to find a paradise at the end of their journey. None return from this pilgrimage, because it leads to almost certain death at the hands of ferocious creatures.[29]

While the Martian females are egg-laying, Martians have mammalian characteristics such as a navel and breasts.[35] While they have skins of various colors, and their bodies differ in some cases from traditional humans, they are very similar to varieties of Earth humans, and there is little examination of how their extraterrestrial biology might make them unusual or particularly distinct from terrestrial humans.[2] There is only one spoken language across the entire planet, but a variety of writing systems.[7]

All Martians are telepathic, among one another, and also with domestic animals. Other telepathic abilities are demonstrated across the books. The Lotharians in Thuvia, Maid of Mars, are able to project images of warfare, that can kill by suggestion.[7]

Trade and cultural relations in Barsoom, as presented by Burroughs, are contradictory. In The Warlord of Mars nations are described as being bellicose and self sufficient, but in The Gods of Mars inter-city state merchants are mentioned, and in Thuvia, Maid of Mars, towering staging posts for inter-city liners are also described.[36]

Most of the cultures are dynasties or theocracies.

Red Martians

The Red Martians are the dominant culture on Barsoom. They are organized into a system of imperial city-states including Helium, Ptarth and Zodanga, controlling the planetary canal system, as well as other, more isolated city-states in the hinterlands. The Red Martians are the interbred descendants of the ancient Yellow Martians, White Martians, and Black Martians, remnants of which exist in isolated areas of the planet, particularly the poles. The Red Martians are said in A Princess of Mars to have been bred when the seas of Barsoom began to dry up, in hopes of creating a hardy race to survive in the new environment.[7][37]

The Red Martians are highly civilized, respect the idea of private property, adhere to a code of honor and have a strong sense of fairness. Their culture is governed by law and is advanced technologically. They are capable of love and have families.[38]

Green Martians

The Green Martians are fifteen feet tall (males) and twelve feet tall (females), have four arms and eyes mounted at the side of their heads. They are nomadic, warlike and barbaric, do not form families, have little concept of friendship or love and enjoy inflicting torture upon their victims. Their social structure is highly communal — they have no concept of private property — and is rigidly hierarchical, consisting of various levels of chiefs, with the highest office occupied by an all powerful Jeddak. However, the title of Jeddak is obtained by mortal combat, rather than hereditary means. They form tribes, which war among one another constantly. They ride aggressive animals, thoats, and armed themselves with swords, lances and firearms which use 'radium' ammunition.[22][38]

The Green Men are primitive, intellectually unadvanced, do not have any kind of art and are without a written language. While they craft weapons, any advanced technology they possess, such as 'radium pistols', is stolen from raids upon the Red Martians. They inhabit the ancient ruined cities left behind by civilizations which lived on Barsoom during a more advanced and hospitable era in the planet's history.[31] They apparently arose from a biological experiment which went awry[citation needed] and as with all other Martians, they are an egg-laying species, concealing their eggs in incubators until hatching. Tars Tarkas, who befriends John Carter when he first arrives on Barsoom, is an unusual exception from the typical ruthless Green Martian, due to having known the love of his own mate and daughter.[22][38]

In the novels, the Green Martians are often referred to by the names of their hordes, which in turn take their names from the dead cities which they inhabit. Thus the followers of Tars Tarkas, based in the ruined ancient city of Thark, are known as "Tharks". Other hordes bear the names of Warhoon, Torquas and Thurd.

Okarians

Yellow Martians are supposedly extinct, but in The Warlord of Mars they are found hiding in secret domed cities at the North Pole of Mars. At the time John Carter arrives on Barsoom the Yellow Race is known only in old wives' tales and campfire stories.

The only means of entrance to the Okarians city is through The Carrion Caves, which are every bit as unpleasant as the name suggests. Air travel over the barrier is discouraged through the use of a great magnetic pillar called "The Guardian of the North," which draws fliers of all sizes inexorably into their doom as they collide with the massive structure.

Their cities are domed hothouses which keep out the cold, but outdoors they favor orluk furs and boots. Physically, they are large and strong, and then men wear bristling black beards as a rule. .[27][38]

White Martians

Orovars

The White Martians, known as 'Orovars' were rulers of Mars for 500,000 years, with an empire of sophisticated cities with advanced technology. They were white skinned, with blond or Auburn hair. They were once a seafaring race but when the oceans began to dry up, they began to cooperate with the Yellow and Black Martians to breed the Red Martians,[39] foreseeing the need for hardy stock to cope with the emerging harsher environment. They became decadent and 'overcivilized'. At the beginning of the series they are believed to be extinct, but three remaining populations, some original Orovars, Therns and Lotharians, are still living in secret and are discovered as the books progress.[7]

Lotharians

The Lotharians are a remnant population of the original White Martians, which appear only in Thuvia, Maid of Mars. There are only 1000 of them remaining, all of them male. They are skilled in telepathy, able to project images that can kill, or provide sustenance. They live a reclusive existence in a remote area of Barsoom, debating philosophy amongst themselves.[40]

Therns

Descendants of the original White Martians who live in a complex of caves and passages in the cliffs above the Valley Dor. This is the destination of the River Iss, on whose currents most Martians eventually travel, on a pilgrimage seeking final paradise, once tired of life or reaching 1000 years of age. The valley is actually populated by monsters, overlooked by the Therns, who control these creatures, and ransack, and eat the flesh of those who perish, enslaving those who survive. They consider themselves a unique creation, different from other Martians. They maintain the false Martian religion through a network of collaborators and spies across the planet. They are themselves raided by the Black Martians. They are white skinned and bald but wear blond wigs.[41]

Black Martians (First Born)

Legend suggests that the Black Martians are inhabitants of one of the moons of Mars, when in fact they live in an underground stronghold near the south pole of the planet, around the subterranean Sea of Omean, below the Lost Sea of Korus, where they keep a large aerial navy. They call themselves the 'First Born', believing themselves to be a unique creation among Martian races, and worship Issus, a woman who styles herself as the God of the Martian religion, but is no such thing. They frequently raid the White Martian Therns, who maintain the false Martian religion, carrying off people as slaves. John Carter defeats their navy in The Gods of Mars.[41]

Others

Kaldanes and Rykors

The Chessmen of Mars introduces the Kaldanes of the region Bantoom, whose form is almost all head but for six vestigial legs and a pair of Chelae, and whose racial goal is to evolve even further towards pure intellect and away from bodily existence. In order to function in the physical realm, they have bred the Rykors, a complementary species composed of a body similar to that of a perfect specimen of Red Martian but lacking a head; when the Kaldane places itself upon the shoulders of the Rykor, a bundle of tentacles connects with the Rykor's spinal cord, allowing the brain of the Kaldane to interface with the body of the Rykor. Should the Rykor become damaged or die, the Kaldane merely climbs upon another as an earthling might change a horse.[7]

Kangaroo Men

A lesser people of Barsoom are the Kangaroo Men of Gooli, so called due to their large, kangaroo-like tails, ability to hop large distances and the rearing of their eggs in pouches. They are presented as a race of boastful, cowardly individuals.[42] Their moral character is not highly developed; they are devout cowards and petty thieves, who only value (aside from their lives) a "treasure" consisting of pretty stones, sea shells, etc.

Hormads

In addition to the naturally occurring races of Barsoom, Burroughs described the Hormads, artificial men created by the scientist Ras Thavas as slaves, workers, warriors, etc. in giant vats at his laboratory in the Toonolian Marsh in Synthetic Men of Mars and "John Carter and the Giant of Mars". Although the Hormads were generally recognizable as humanoid, the process was far from perfect, and generated monstrosities ranging from the occasional misplaced nose or eyeball to "a great mass of living flesh with an eye somewhere and a single hand." [43]

Technology

When Burroughs wrote the first volume of the Barsoom series, aviation and radio technology was in its infancy and radioactivity was a fledgling science. Despite this, the series includes a range of technological developments including radium munitions, battles between fleets of aircraft, devices similar to faxes and televisions, genetic manipulation, elements of terraforming and other ideas. One notable device mentioned is the "directional compass"; this may be believed to be the precursor to the now-common "global positioning system", or GPS for short.[44]

Fliers

The Red Martians have flying machines, both civilian transports, and fleets of heavily armed war craft. These stay aloft through some form of anti-gravity, which Burroughs explains as relating to the rays of the Sun.[7] Fliers travel at approximately 166.1 earth miles per hour (450 Martian Haads per hour).[45]

In Thuvia, Maid of Mars, John Carter's son, Cathoris, invents what appears to be a partial precursor of the autopilot (several decades before this became a reality). The device, built upon existing Martian compass technology, allows the pilot to reach any programmed destination, only having to keep the craft pointed in the set direction. Upon arrival, the device automatically lowers the craft to the surface. He also includes a kind of collision detector, which uses radium rays to detect any obstacle and automatically steer the craft elsewhere, until the obstacle is no longer detected.[46] This works in principle almost identically to the backscatter radiation detector used to fire the braking rockets on the Soyuz space capsule. In Swords of Mars a flier with some kind of mechanical brain is introduced. Controlled by thought, it can be remote controlled in flight, or instructed to travel to any destination.[47]

Weapons

Firearms are common, and use 'Radium' bullets, which explode when exposed to sunlight. Some weapons are specific to races or inventors. The mysterious Yellow Martians, who live in secret glass domed cities at the poles, and appear in The Warlord of Mars have a form of magnet which allows them to attract flying craft and cause them to crash. Scientist Phor Tak, who appears in A Fighting Man of Mars, has developed a disintegrator ray, and also a paste which renders vehicles such as fliers impervious to its effects. He also develops a missile which seeks out craft protected in this fashion, and a means of rendering fliers invisible which becomes a key plot device in the novel. However, while advanced weapons are available, most martians seem to prefer melee combat — mostly with swords — and their level of skill is highly impressive.[7]

Atmosphere plant

They are many technological wonders in the novels, some colossal works of engineering. The failing air of the dying planet is maintained by an atmosphere plant, and the restoration of this is a plot component of A Princess of Mars.[7] It is described as being four miles across with walls 100 feet in depth, and telepathically operated entrance doors of 20-foot-thick (6.1 m) steel.[15]

Medicine and biology

Martian medicine is generally greatly in advance of that on Earth.[48] In The Master Mind of Mars aging genius, Ras Thavas, has perfected the means of transplanting organs, limbs and brains, which during his experiments he swaps between animals and humanoids, men and women and young and old.[7] Later, in Synthetic Men of Mars, he discovers the secret of life, and creates an army of artificial servants and warriors, which are grown in giant vats filled with organic tissue. They frequently emerge deformed, are volatile and are difficult to control, later threatening to take over the planet.[49]

Measurements

Burroughs developed a system of Martian measurements for the novels. He also drew maps for his own reference while writing, which used the Martian haad as a unit of length. Martian measurements include the following[45][50]

| Unit | Martian | Imperial | Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 sofad | 11.68+ inches | 0.2967 m | |

| 10 sofads = 1 ad | 9.75 feet | 2.97 m | |

| 200 ads = 1 haad | 1,949.05 feet | 594.07 m | |

| 100 haads = 1 karad | 36.92 English miles | 59.407 km | |

| 2.709 haads | 1 English mile | 1609 m | |

| 1.683 haads | 0.621 English miles | 1000 m |

Clothing

The Martians wear no clothing other than jewelry and leather harnesses, which are designed to hold everything from the weaponry of a warrior to pouches containing toiletries and other useful items; the only instances where Barsoomians habitually wear clothing is for need of warmth, such as for travel in the northern polar regions described in The Warlord of Mars.

This preference for near-nudity provides a stimulating subject for illustrators of the stories, though art for many mass-market editions of the books feature Carter and native Barsoomians wearing loincloths and other minimal coverings, or use strategically placed shadows and such to cover genitalia and female breasts.

Fauna

It appears that most of Burrough’s Martian creatures are roughly equivalent to those found on Earth. Though in general, most seem to have multiple legs and all are egg-laying.

“Insects”, "reptiles" and "birds"

- Sith: A giant, venomous hornet-like insect endemic to the Kaolian Forest.[51]

- Reptiles: Are described as repulsive and usually poisonous, and include

- Darseen, a chameleon-like reptile.

- Silian, an Antarctic sea-monster found in the Lost Sea of Korus.

- Birds: Burroughs tells us that Martian birds are brilliantly plumed, but the only species actually described is the enormous Malagor, native to the Great Toonolian Marshes.

“Mammals”

The martian mammalian equivalents all have fur, and both domestic and wild varieties are described by Burroughs.

Domesticated

- Sorak: A small six-legged creature, equivalent to a cat.

- Calot: A large dog-like creature with a frog-like mouth and three rows of teeth. John Carter has his own calot, named Woola, who is his faithful companion during The Warlord of Mars.

- Thoat: A Martian horse. It has four legs on each side of its body and a wide, flat tail, which is larger at the base than at the apex and which is extended while running. The Greater Thoat is used as a mount by the Green Martians and stands about ten feet high at the shoulder; the Lesser Thoat bred by the Red Martians is closer to Earth horses in size. The Thoat is described as a slate-colored animal, with a white underside and yellow lower legs and feet.

- Zitidar: A draft animal, described as being similar to mastodons.

Wild

- Apt: A large white-furred arctic creature with six limbs, four being legs, which give it rapid speed, and two being arms with hairless hands, with which it grasps prey. It has tusks growing from its lower jawbone, and large faceted, insect-like eyes. Appears in The Warlord of Mars.[51]

- Banth: A Barsoomian "lion". It hunts the hills surrounding the dead seas of Barsoom. It has a long, sleek body, with ten legs, large jaws equipped with several rows of sharp fangs in a mouth which extends back almost to small ears. It is mostly hairless, except for a thick mane around the neck. It has large, protruding green eyes.[52]

- Ulsio: A kind of Barsoomian "rat", described as a dog-sized burrower.

- White Ape: Huge and ferocious, semi-intelligent gorilla-like creatures with an extra set of arms which first appear in A Princess of Mars.

Other

- Rykors are headless but otherwise human-like creatures bred by the Kaldanes, appearing only in The Chessmen of Mars.

- Plant Men: Monsters found in the Valley Dor. They are between 10 and 12 feet in height when upright, with blue hairless bodies similar in form to humans, excepting broad flat feet which are three feet in length and a six foot tail, which tapers from a round profile to a flat blade shape at the tip. They also have short, sinuous arms similar to elephant trunks, ending with taloned hands, with mouths set in the palms. The creature uses these to feed on foliage.[53] It also attacks and feeds upon Martian Pilgrims, who travel to the Valley Dor expecting to find final paradise.[29] Their faces are without mouths, a nose like an open wound, have a single white eye, surrounded by a white band, and black hair 10 to 12 inches long, each strand similar in thickness to an earthworm. They appear in The Gods of Mars.[53]

- Orluk: An Arctic predator with a black and yellow striped coat, whose legs are not described.

Themes

American frontier

Barsoom might be seen as a kind of Martian Wild West. John Carter is himself an adventuring frontiersman. When he arrives on Barsoom he first compares it to the landscape of Arizona which he has left behind. He discovers a savage, frontier world where the civilized Red Martians are kept invigorated as a race by repelling the constant attacks of the Green Martians, a possible equivalent of Wild West ideals. Indeed, the Green Martians are a barbaric, nomadic, tribal culture with many parallels to stereotypes of American Indians. The desire to return to the frontier became common in the early 20th century America. As the United States become more urbanized, the world of the 19th century frontier America became romanticized as a lost world of freedom and noble qualities.[31]

Race

Race is a constant theme in the Barsoom novels and the world is clearly divided along racial lines. White, Yellow, Black, Red and Green races all appear across the novels, each with particular traits and qualities which seem to define the characters of almost every individual within them. In this respect, Burroughs' concept of race, as depicted in the novels, is more like a division between species. The Red and Green Martians are almost complete opposites of one another, with the Red Martians being civilized, lawful, capable of love and forming families, and the Green Martians being savage, cruel, tribal and without families or the ability to form romantic relationships.[38]

Religious deception

The Barsoom series features a number of incidences of religious deception, or the use of superstition by those in power to control and manipulate others.[18] Burroughs is particularly concerned about the hypocrisy of religious leaders.[54] This is first established in A Princess of Mars,[18] but becomes particularly apparent in the sequel, The Gods of Mars. Upon reaching 1,000 years of age almost all Martians undertake a pilgrimage on the River Iss, expecting to find a valley of mystical paradise; what they find is, in fact, a deathtrap, populated by ferocious creatures and overseen by a race of cruel, cannibal priests known as Therns, who perpetuate the Martian religion through a network of spies across the planet.[29]

John Carter's battle to track down the remnants of the Therns and their masters continues in the sequel, The Warlord of Mars.[27] More deceitful priests in a nation controlled by such appear in The Master Mind of Mars, on this occasion manipulating a temple idol to control followers.[27]

Burroughs continued this theme in his many Tarzan novels. Burroughs was not anti-religious; however, he was concerned about followers placing their trust in religions and being abused and exploited, and saw this as a common feature of organized religion.[54]

Excessive intellectualism

While Burroughs is generally seen as a writer who produced work of limited philosophical sophistication, he wrote two Barsoom novels which appear to explore or parody the limits of excessive intellectual development at the expense of bodily or physical existence. The first was Thuvia, Maid of Mars, in which Thuvia and Carthoris discover a remnant of ancient White Martian civilization, the Lotharians. The Lotharians have mostly died out, but maintain the illusion of a functioning society through powerful telepathic projections. They have formed two factions which appear to portray the excesses of pointless intellectual debate. One faction, the realists, believes in imagining meals to provide sustenance; another, the etherealists, believes in surviving without eating.

The Chessmen of Mars is the second example of this trend. The Kaldanes have sacrificed their bodies to become pure brain, but although they can interface with Rykor bodies, their ability to function, compared to normal people of integrated mind and body, is ineffectual and clumsy.[55] The Kaldanes, though highly intelligent, are ugly, ineffectual creatures when not interfaced with a Rykor body. Tara of Helium compares them to effete intellectuals from her home city, with a self-important sense of superiority; and Gahan of Gathol muses that it might be better to find a balance between the intellect and bodily passions.[28]

Paradox of "Superiority"

Some of Barsoom's peoples especially the Therns and First Born hold themselves as "superior" to the "lesser order" peoples on Barsoom. A paradox is established in that the Therns and First Born though they hold themselves in such high esteem, nonetheless are dependent on these lesser orders for their sustainance, labor, and goods as the Therns and First Born are "non-productive" peoples and do not produce anything or invent as such labor is seen as beneath them. Thus the implication is if they are so utterly dependent, then are they really "superior?" This is punctuated by the fact that the Therns and First Born are obliged to create strongholds in the southpole to insulate themselves from the otherwise red and green Martian dominated planet.

Antecedents and influences on Burroughs

Scientific inspiration

Burroughs concept of a dying Mars and the Martian canals follows the theories of Lowell and his predecessor Giovanni Schiaparelli. In 1878, Italian astronomer, Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli observed geological features on Mars which he called canali (Italian: "channels"). This was mistranslated into the English as "canals" which, being artificial watercourses, fueled the belief that there was some sort of intelligent extraterrestrial life on the planet. This further influenced American astronomer Percival Lowell.[56]

In 1895 Lowell published a book titled Mars which speculated about an arid, dying landscape, whose inhabitants had been forced to build canals thousands of miles long to bring water from the polar caps to irrigate the remaining arable land.[30] Lowell followed with Mars and Its Canals (1906) and Mars as an Abode of Life (1908). This formed prominent scientific ideas about the conditions on the red planet in the early years of the 20th century. Although Burroughs does not seem to have based his vision of Mars on precise reading of Lowell's theories, as there are a number of errors in his ideas which may suggest he got most of his information from reading newspaper articles and other popular accounts of Lowell's Mars.[57]

The concept of canals with flowing water and a world where life was possible were later proved erroneous by more accurate observation of the planet, and later landings by Russian and American probes such as the two Viking missions which found a dead world too cold for water to exist in its fluid state.[30]

Previous Mars fiction

The first science fiction to be set on Mars may be Across the Zodiac, by Percy Greg, published in 1880. It was a long-winded book concerned with a civil war on Mars. Another Mars novel, dealing with benevolent Martians coming to Earth was published in 1897 by Kurd Lasswitz, Auf Zwei Planeten. It was not translated until 1971, and was thus unlikely to have influenced Burroughs, although it did depict a Mars influenced by the ideas of Percival Lowell.[58] Other examples are Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet (1889), which took place on Mars; Gustavus W. Popes's Journey to Mars (1894); and Ellsworth Douglas's Pharaoh's Broker, in which the protagonist encounters an Egyptian civilization on Mars which, while parallel to that of the Earth, has evolved somehow independently.[9]

H.G. Wells' novel, The War of the Worlds, most definitely influenced by Lowell and published in 1898, did however create the precedent for a number of enduring Martian tropes in science fiction writing. These include Mars being an ancient world, nearing the end of its life; being the home of a superior civilization, capable of advanced feats of science and engineering; and a source of invasion forces, keen to conquer the Earth. The first two tropes were prominent in Burroughs' Barsoom series.[30] Burroughs, however, claimed never to have read any of H.G. Wells' books.[59] Lowell was probably the greater direct influence on Burroughs.[60]

Richard A. Lupoff claimed that Burroughs was influenced in writing his Martian stories by Edwin Lester Arnold's earlier novel Lieutenant Gullivar Jones: His Vacation (1905) ( later retitled Gulliver of Mars). Gullivar Jones, who travels to Mars by flying carpet rather than via astral projection, encounters a civilization with similarities to those found on Barsoom, rescues a Martian Princess, and even undertakes a voyage down a river similar to the Iss in The Gods of Mars. Lupoff also suggested that Burroughs derived characteristics of his main protagonist John Carter from Phra, hero of Arnold's The Wonderful Adventures of Phra the Phoenician (1890), who is also a swashbuckling adventurer and master swordsman, for whom death is no obstacle. Lupoff's theories were disputed by numerous scholars of Burroughs' work. Lupoff countered, claiming that many of Burroughs' stories had antecedents in previous works, and that this was not unusual for writers.[61]

Burroughs' influence

Scientists

Burroughs' Barsoom series was extremely popular with American readers and many scientists who grew up reading the novels, and helped inspire public support for the US space program. Readers included some of the first space pioneers and those involved in the search for life on other planets. Scientist Carl Sagan read the books as a young boy, and they continued to affect his imagination into his adult years.[62] He remembered Barsoom as a "world of ruined cities, planet girdling canals, immense pumping stations — a feudal technological society". For two decades, a map of the planet, as imagined by Burroughs, hung in the hallway outside of Sagan's office in Cornell University.[60]

Science fiction

Well-known early science fiction writers Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke both read, and were inspired by Burroughs' series of Barsoom books in their youth. Bradbury admired Burroughs' stimulating romantic tales, and they were an inspiration for The Martian Chronicles (1950), in which he used some similar concepts of a dying Mars. Robert A. Heinlein also wrote fiction inspired by Burroughs' Barsoom series, and for many others, the Barsoom series helped to establish Mars as an adventurous, enticing destination for the imagination.[63][64]

The John Carter books enjoyed another wave of popularity in the 1970s, with Vietnam War veterans who said they could identify with Carter, fighting in a war on another planet.[citation needed]

Novels and short stories

Numerous novels and series by others were inspired by Burroughs' Mars books: the Radio Planet trilogy of Ralph Milne Farley; the Mars and Venus novels of Otis Adelbert Kline; Almuric by Robert E. Howard; Warrior of Llarn and Thief of Llarn by Gardner Fox; Tarzan on Mars, Go-Man and Thundar, Man of Two Worlds by John Bloodstone; the Michael Kane trilogy of Michael Moorcock; The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, Through the Gates of the Silver Key by H.P. Lovecraft, the Gor series of John Norman; the Callisto series and Green Star series of Lin Carter; The Goddess of Ganymede and Pursuit on Ganymede by Mike Resnick; and the Dray Prescot series of Alan Burt Akers (Kenneth Bulmer). In addition, Leigh Brackett, Ray Bradbury, Andre Norton, Marion Zimmer Bradley, and Alan Dean Foster show Burroughs' influence in their development of alien cultures and worlds.

A. Bertram Chandler's pulp novels The Alternate Martians and The Empress of Outer Space overtly borrow a number of characters and situations from Burroughs' Barsoom series.

Robert A. Heinlein's novels Glory Road and The Number of the Beast, and Alan Moore's graphic novels of Allan and the Sundered Veil and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume II directly reference Barsoom.

In Philip José Farmer's World of Tiers series (1965–1993) Kickaha, the series' adventurer protagonist, asks his friend The Creator of Universes to create for him a Barsoom. The latter agrees only to make an empty world, since "It would go too far for me to create all these fabulous creatures only for you to amuse yourself by running your sword through them." Kickaha visits from time to time the empty Barsoom, complete with beautiful palaces in which nobody ever lived, but goes away frustrated.

L. Sprague de Camp's story "Sir Harold of Zodanga" recasts and rationalizes Barsoom as a parallel world visited by his dimension-hopping hero Harold Shea. De Camp accounts for Burroughs' departures from physics or logic by portraying both Burroughs and Carter as having a tendency to exaggerate in their storytelling, and Barsoomian technology as less advanced than usually presented.

Furthermore, his Viagens Interplanetarias series of novels and short stories, especially those set on Krishna, one of Tau Ceti's inhabited planets, owe much to the premise of feudal co-existence alongside advanced technology pioneered within the Barsoom series.

In 1989 Larry Niven and Steven Barnes published "The Barsoom Project", where a futuristic form of live action role-playing games (LARPs) is based on the Barsoom books.

The Mars-based novels of Kim Stanley Robinson (published from 1992 to 1999) also offer several nods in Burroughs' direction.

The 2008 novel In the Courts of the Crimson Kings by S.F. writer S. M. Stirling is an alternate telling of the Princess of Mars story but this time the princess is a very powerful character indeed.

DC Comics character Adam Strange's method of transportation, the Zeta Beam, recalls the way Carter is transported to Mars.

In the Commonwealth Saga novels by Peter F. Hamilton a group of humans who undertake unprecedented and often illegal genetic modifications of their own bodies are known as the Barsoomians, in apparent reference to Burroughs' creation.

Richard Corben's Den series also appears to be inspired by the Barsoom series. It features a hero, Den, who mysteriously arrives naked on a (largely) desert planet where he becomes a great warrior and where the humanoids wear no clothes. Many of the creatures resemble the description of the white apes of the Gods of Mars. Like John Carter, he also receives great physical prowess from arriving in Neverwhere, although Carter's prowess stems from gravity, whereas Den undergoes a complete physical transformation.

In Stephen King's novel The Dark Tower II: The Drawing of the Three, Eddie Dean compares the All-World and the quest for the Dark Tower to a Barsoom novel.

The John Carter of Mars series was also felt to be one of the inspirations for the Dark Sun Dungeons & Dragons game world setting.

In A Wizard of Mars by Diane Duane, the main character Kit is a major fan of the Barsoom series and a long dormant wizard artifact recreates Barsoom as Kit imagines it to communicate with him.

Poetry

The science fiction poems in Oscar Hurtado's book La Ciudad Muerta de Korad (The Dead City of Korad, in Spanish) are full of intertextualities with the Barsoom series, as well as with the Sherlock Holmes novels by Arthur Conan Doyle, the Iliad, children folk tales, and other references.

The Dead City of Korad was published in 1964 and marks the beginning of the Science Fiction genre in Cuba.[65]

Film and television

- Avatar: In interviews, James Cameron has invoked Burroughs as one of the primary inspirations behind his 2009 space adventure.[66]

- Babylon 5: In this science fiction television series, Amanda Carter — a Martian citizen and advocate of Mars' independence from Earth — is revealed to have had a grandfather named John who was a pioneer colonist on Mars. This has been confirmed by the series creator J. Michael Straczynski as a reference made by the episode writer Larry DiTillio to John Carter of Mars.[67]

- Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers film serials of the 1930s, and the Star Wars films owe debts and offer nods to Burroughs' Barsoom novels

Adaptations

Comic strips

With the Tarzan comic strip a popular success, newspapers began a comic strip adaptation of A Princess of Mars drawn by Edgar Rice Burroughs' son, John Coleman Burroughs. Never as popular as Tarzan, it ran in only four Sunday newspapers, from December 7, 1941 to March 28, 1943.

John Carter appeared in one of the last Sunday Tarzan comic strip stories, drawn by Gray Morrow.

Comic books

- The Funnies: This comic book included a John Carter serial drawn by John Coleman Burroughs, which ran for 23 issues.

- John Carter (Dell Comics): Dell published published three comic books in 1952, adapting the first three Barsoom books, drawn by Jesse Marsh, who was the Dell Tarzan artist at the time. They were Four Color Comics #375, 437, and 488. They were later reprinted by the successor of Dell, Gold Key Comics as John Carter of Mars #1-3.

- A Princess of Mars (The Sun): This UK comic ran as a weekly serial in 1958 adapted by Robert Forrest.

- John Carter in Tarzan (DC Comics): John Carter was published as a backup feature in the Tarzan series, issues 207–209, after which it was moved to Weird Worlds, sharing main feature status alongside an adaptation of Burroughs' "Pellucidar" stories in issues #1-7; it again became a backup feature in Tarzan Family #62-64. (A non-John Carter Barsoom story also appeared in Tarzan Family issue #60.)

- John Carter, Warlord of Mars (Marvel Comics): This series began in 1977 and lasted for 28 issues (and saw three annuals published).

- Tarzan comic strip: In 1995, writer Don Kraar set a story on Barsoom featuring Tarzan, David Innes, and John Carter.

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (DC Comics): John Carter also made a notable cameo in the second volume of the series written by Alan Moore. Along with other literary Martian characters, he leads a campaign against the Martians from The War of the Worlds.

- ABC Magazine, Czechoslovakia: The first four Barsoom novels were printed as two comic-book series (51 pages altogether) from 1970-1972 (Written by Vlastislav Toman, with painters Jiří Veškrna and Milan Ressel.) They were reprinted in 2001 in the comic book Velká Kniha Komiksů I. (ISBN 80-7257-658-5)

- Warlord of Mars (Dynamite Entertainment): Starting in October 2010, Dynamite has begun publishing a twelve-issue series entitled Warlord of Mars. The first two issues served as a prelude story, issues 3-9 adapted A Princess of Mars, and issues 10-12 will be an original story.

- Warlord of Mars: Dejah Thoris (Dynamite Entertainment): Starting in March 2011, it is set 400 years before A Princess of Mars and focus on Dejah Thoris, her first suitor, and her role in the rise to power of the Kingdom of Helium.

- Warlord of Mars: Fall of Barsoom (Dynamite Entertainment): Starting in July 2011, it is be set 100,000 years before A Princess of Mars and focus on the attempt of two Orovars to save Mars as the seas dry up and the atmosphere becomes thin.

Film

Princess of Mars, was a 2009 direct-to-video film, produced by The Asylum, starring Antonio Sabato Jr. as John Carter, and Traci Lords as Dejah Thoris. This adaptation starts with John Carter as a present day sniper wounded in Afghanistan, and then teleported to another world as a part of a government experiment. This adaptation does not resemble the original work of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

John Carter, was released on March 9th, 2012, as a big budget film by The Walt Disney Company, directed by Andrew Stanton and stars Taylor Kitsch as John Carter, and Lynn Collins as Dejah Thoris.

Copyright

The American copyright of the five earliest novels has expired in the United States, and they appear on a number of free e-text sites. However, because they were separately copyrighted in Great Britain, these works remain protected under the Berne Copyright Convention in the UK and throughout much of the world. The Australian copyright of the remainder, not including John Carter of Mars (1964), has also expired and they too appear online.

See also

- Jetan, a game invented by Burroughs and described in The Chessmen of Mars

- Pellucidar

References

- ^ Clareson, Thomas D. (1971). SF: the Other Side of Realism. Popular Press. p. 229. ISBN 0879720239.

- ^ a b c Dick, Steven J. (1999). The Biological Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 239. ISBN 0195171810, 9780195171815.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Stableford, Brian (2006). Science Fact and Science Fiction. CRC Press. p. 284. ISBN 0415974607.

- ^ a b Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1990). Science Fiction, the Early Years. Kent State University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0873384164.

- ^ a b Bainbridge, Williams Sims (1986). Dimensions of Science Fiction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-674-20725-4, 9780195171815.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) Cite error: The named reference "bainbridge131" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Westfahl, Gary (2005). Greenwood encyclopedia of science fiction and fantasy: themes, works, and wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1209–10. ISBN 0313329532.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1990). Science Fiction, the Early Years. Kent State University Press. pp. 95–101. ISBN 0873384164.

- ^ Porges, Irwin (1975). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. p. 664. ISBN 4500-30482.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b c d Westfahl, Gary (2000). Space and Beyond. Greenwood Publishing Groups. p. 38. ISBN 0313308462.

- ^ Harris-Fain, Darren (2005). Understanding Contemporary American Science Fiction. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 147. ISBN 1570035857.

- ^ White, Craig (2006). Student Companion to James Fenimore Cooper. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 143. ISBN 0313334137.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2005). Greenwood encyclopedia of science fiction and fantasy: themes, works, and wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1210. ISBN 0313329532.

- ^ Sharp, Patrick B. (2007). Savage Perils. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 080613822X.

- ^ a b Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ a b Sampson, Robert (1984). Yesterday's Faces: A Study of Series Characters in the Early Pulp Magazines. Popular Press. p. 180. ISBN 0879722622.

- ^ a b Sampson, Robert (1984). Yesterday's Faces: A Study of Series Characters in the Early Pulp Magazines. Popular Press. p. 183. ISBN 0879722622.

- ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ a b c Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2005). Greenwood encyclopedia of science fiction and fantasy: themes, works, and wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1210–11. ISBN 0313329532.

- ^ a b Sampson, Robert (1984). Yesterday's Faces: A Study of Series Characters in the Early Pulp Magazines. Popular Press. p. 177. ISBN 0879722622.

- ^ a b c d Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1990). Science Fiction, the Early Years. Kent State University Press. p. 96. ISBN 0873384164.

- ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. pp. 28–9. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Sharp, Patrick B. (2007). Savage Perils. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 95. ISBN 080613822X.

- ^ a b c d e Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1990). Science Fiction, the Early Years. Kent State University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0873384164. Cite error: The named reference "bleiler7" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ a b c d Sampson, Robert (1984). Yesterday's Faces: A Study of Series Characters in the Early Pulp Magazines. Popular Press. p. 182. ISBN 0879722622.

- ^ a b c d Baxter, Stephen (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "H.G. Wells' Enduring Mythos of Mars". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 186–7. ISBN 1932100555, 9781932100556.

{{cite journal}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c Sharp, Patrick B. (2007). Savage Perils. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 94. ISBN 080613822X.

- ^ Slotkin, Richard (1998). Gunfighter Nation. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 205. ISBN 0806130318.

- ^ Clareson, Thomas D. (1971). SF: the Other Side of Realism. Popular Press. pp. 230–32. ISBN 0879720239.

- ^ Harris-Fain, Darren (2005). Understanding Contemporary American Science Fiction. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 148. ISBN 1570035857.

- ^ Clareson, Thomas D. (1971). SF: the Other Side of Realism. Popular Press. pp. 244–5. ISBN 0879720239.

- ^ Clareson, Thomas D. (1971). SF: the Other Side of Realism. Popular Press. p. 245. ISBN 0879720239.

- ^ Bainbridge, Williams Sims (1986). Dimensions of Science Fiction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-674-20725-4, 9780195171815.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c d e Slotkin, Richard (1998). Gunfighter Nation. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 203–205. ISBN 0806130318.

- ^ Prakash, Gyan; Kruse, Kevin Michael (2008). The Spaces of the Modern City. Princeton University Press. p. 72. ISBN 0691133433.

- ^ Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1990). Science Fiction, the Early Years. Kent State University Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0873384164.

- ^ a b Bleiler, Everett Franklin; Bleiler, Richard (1990). Science Fiction, the Early Years. Kent State University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0873384164.

- ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. p. 591. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Synthetic Men of Mars, Chapter VII

- ^ Hogan, James P. (2003). Introduction: Under the Moons of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs. U of Nebraska Press. p. xv. ISBN 0-8032-6208-6.

- ^ a b Porges, Irwin (1975). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. p. 170. ISBN 4500-30482.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Porges, Irwin (1975). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. p. 213. ISBN 4500-30482.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Porges, Irwin (1975). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. p. 542. ISBN 4500-30482.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. pp. 25–6. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Telotte, J.P. (1995). Replications. University of Illinois Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0252064666.

- ^ http://www.erblist.com/abg/maps.html

- ^ a b Porges, Irwin (1975). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. p. 163. ISBN 4500-30482.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Burroughs, Edgar Rice (2004). Thuvia Maid of Mars (Glossary). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 248–9. ISBN 141792330X.

- ^ a b Burroughs, Edgar Rice (2004). Thuvia Maid of Mars (Glossary). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 252–3. ISBN 141792330X.

- ^ a b Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ Scholes, Robert; Rabkin, Eric S. (1977). Science Fiction: Story.Science.Vision. Oxford University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-19-502174-6.

- ^ Seed, David (2005). A Companion to Science Fiction. Blackwell Publishing. p. 546. ISBN 1405112182, 9781405112185.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Clareson, Thomas D. (1971). SF: the Other Side of Realism. Popular Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 0879720239.

- ^ Hotakainen, Markus (2008). Mars: A Myth Turned to Landscape. Springer. p. 205. ISBN 0387765077.

- ^ Holtsmark, Erling B. (1986). Edgar Rice Burroughs. Boston: Twain Publishers. p. 38. ISBN 0-8057-7459-9.

- ^ a b Basalla, George (2006). Civilized Life in the Universe: Scientists on Intelligent Extraterrestrials. Oxford University Press US. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0195171810, 9780195171815.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Lupoff, Richard A. (2003), Introduction to: Gullivar of Mars by Edwin Lester Linden Arnold. University of Nebraska Press. vii-xvi. ISBN 0-8032-5942-5

- ^ Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, episode "Blues for a Red Planet"

- ^ Dick, Steven J. (1999). The Biological Universe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN 0195171810, 9780195171815.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Parrett, Aaron (2004), Introduction to: The Martian Tales Trilogy by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Barnes & Noble Publishing. xiii-xvi. ISBN 0-7607-5585-X

- ^ Gerardo Chávez Spínola (2002), "Mínima crónica sobre un gigante" ("Small Chronic About a Giant", in Spanish), Guaicán Literario. Retrieved 2010-05-28

- ^ Quoted in "The New Yorker" [1]. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- ^ J. Michael Straczynski, (1994), "JMS usenet posting", rec.arts.sf.tv.babylon5.moderated. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- Roy, John Flint (1976). A Guide to Barsoom. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-24722-1-175.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid prefix (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- barsoom.com site from ERB, Inc., Tarzana, CA

- Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Web Site

- Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs

- A Guide to Barsoom — the official guide to ERB's Barsoom

- Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

- A Guide to the Mars Novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Maps of Barsoom

- A Barsoom Glossary

- Panthan Press published The Barsoomian Blade newspaper and the Dateline Jasoom podcast

- Barsoom series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- A Princess of Mars at Project Gutenberg

- The Gods of Mars at Project Gutenberg

- Warlord of Mars at Project Gutenberg

- Thuvia, Maid of Mars at Project Gutenberg

- The Chessmen of Mars at Project Gutenberg

- The Master Mind of Mars (1927) Zip file Text file at Project Gutenberg Australia

- A Fighting Man of Mars (1930) Zip file Text file at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Swords of Mars (1934) Zip file Text file at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Synthetic Men of Mars (1940) Zip file Text file at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Llana of Gathol (1948) Zip file Text file at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Internet Movie Database

- unofficial fan site