Chogha Zanbil: Difference between revisions

Reverted good faith edits by 109.228.140.177 (talk): Unreferenced and poss WP:BLP; is Robert Gishman still alive? (TW) |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Choghazanbil enterrior excavations were carbon-dated and placed its building around 2300 to 2360 BCE. by the time non of Mesopotamian Ziggurats were not yet built. |

|||

Another important aspect is the inclusion of one hole city around this building that Prof. Gishman missed it totally. |

|||

More over the enterrance to the Ziggurat is unique and has no resembllence to those of later built in Iraq. |

|||

The City of Sousa and Andamaska were very much in trade with the kingdom of Awan and Choghazanbil. |

|||

The pro-biblical historians of mesopotamia never liked to see that their theories and their documents were not 100 % right so as an unwritten rule they kept playing done the impact of much older kingdoms on Sumerians and Babylonians. |

|||

Choga Zambil means 'basket mound.'<ref>Rohl, D: ''Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation'', page 82. Century, 1998.</ref> It was built about 1250 BC by the king [[Untash-Napirisha]], mainly to honor the great god [[Inshushinak]]. Its original name was ''Dur Untash'', which means 'town of Untash', but it is unlikely that many people, besides priests and servants, ever lived there. The complex is protected by three concentric walls which define the main areas of the 'town'. The inner area is wholly taken up with a great ziggurat dedicated to the main god, which was built over an earlier square temple with storage rooms also built by Untash-Napirisha. |

Choga Zambil means 'basket mound.'<ref>Rohl, D: ''Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation'', page 82. Century, 1998.</ref> It was built about 1250 BC by the king [[Untash-Napirisha]], mainly to honor the great god [[Inshushinak]]. Its original name was ''Dur Untash'', which means 'town of Untash', but it is unlikely that many people, besides priests and servants, ever lived there. The complex is protected by three concentric walls which define the main areas of the 'town'. The inner area is wholly taken up with a great ziggurat dedicated to the main god, which was built over an earlier square temple with storage rooms also built by Untash-Napirisha. |

||

<ref>R Ghirshman, The Ziggurat of Tchoga-Zanbil, Scientific American, vol. 204, pp. 69-76, 1961</ref> |

<ref>R Ghirshman, The Ziggurat of Tchoga-Zanbil, Scientific American, vol. 204, pp. 69-76, 1961</ref> |

||

Revision as of 10:13, 2 June 2012

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv |

| Reference | 113 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

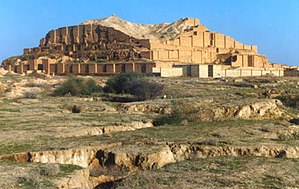

Chogha Zanbil (Persian: چغازنبيل); Elamite: Dur Untash) is an ancient Elamite complex in the Khuzestan province of Iran. Chogha in Bakhtiari means hill. It is one of the few existent ziggurats outside of Mesopotamia. It lies approximately 42 kilometeres south-southwest of Dezfoul, 30 kilometres west of Susa and 80 kilometres north of Ahvaz.

History

Choga Zambil means 'basket mound.'[1] It was built about 1250 BC by the king Untash-Napirisha, mainly to honor the great god Inshushinak. Its original name was Dur Untash, which means 'town of Untash', but it is unlikely that many people, besides priests and servants, ever lived there. The complex is protected by three concentric walls which define the main areas of the 'town'. The inner area is wholly taken up with a great ziggurat dedicated to the main god, which was built over an earlier square temple with storage rooms also built by Untash-Napirisha. [2] The middle area holds eleven temples for lesser gods. It is believed that twenty-two temples were originally planned, but the king died before they could be finished, and his successors discontinued the building work. In the outer area are royal palaces, a funerary palace containing five subterranean royal tombs.

Although construction in the city abruptly ended after Untash-Napirisha's death, the site was not abandoned, but continued to be occupied until it was destroyed by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 640 BC. Some scholars speculate, based on the large number of temples and sanctuaries at Chogha Zanbil, that Untash-Napirisha attempted to create a new religious center (possibly intended to replace Susa) which would unite the gods of both highland and lowland Elam at one site.

The ziggurat is considered to be the best preserved example in the world. In 1979, Chogha Zanbil became the first Iranian site to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Archaeology

Choga Zanbil was excavated in six seasons between 1951 and 1961 by Roman Ghirshman. [3] [4] [5] [6][7]

Threats

Petroleum exploration in the region threatens the very foundations of the site, as various seismic tests have been undertaken to explore for reserves of petroleum. Digging for oil has been undertaken as close as 300 meters away from the ziggurat.[8]

See also

- Step pyramid

- Iranian architecture

- List of Iranian castles, citadels, and fortifications

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

Notes

- ^ Rohl, D: Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation, page 82. Century, 1998.

- ^ R Ghirshman, The Ziggurat of Tchoga-Zanbil, Scientific American, vol. 204, pp. 69-76, 1961

- ^ Roman Ghirshman, Travaux de la mission archéologique en Susiane en hiver 1952-1953, Syria, T. 30, Fasc. 3/4, pp. 222-233, 1953

- ^ Roman Ghirshman, Tchoga Zanbil (Dur-Untash). Vol. I: La Ziggurat, Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique en Iran, vol. 39, Geuthner, 1966

- ^ R. Ghirshman, Tchoga Zanbil (Dur-Untash) Volume II: Temenos, Temples, Palais, Tombes, Memoires de la Delegation Archeologique en Iran, vol. 40 Geuthner, 1968

- ^ M.J. Steve, Tchoga Zanbil (Dur-Untash) 3: Textes Élamites et Accadiens, Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique en Iran, vol. 41, Geuthner, 1967

- ^ Edith Porada, Tchoga Zanbil (Dur-Untash). Vol. IV (only): La Glyptique, Memoires de la Delegation Archeologique en Iran, vol. 42, Geuthner, 1970

- ^ Soudabeh Sadigh (November 29, 2006). "Seismographic Tests to be performed on Tchogha Zanbil". Cultural Heritage News Agency.

References

- D. T. Potts, The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-56496-4

- Roman Ghirshman, La ziggourat de Tchoga-Zanbil (Susiane), Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 98 lien Issue 2, pp. 233-238, 1954

- Roman Ghirshman, Campagne de fouilles à Tchoga-Zanbil, près de Suse, Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 99, iss. 1, pp. 112-113, 1955

- Roman Ghirshman, Cinquième campagne de fouilles à Tchoga-Zanbil, près Suse, rapport préliminaire (1955-1956), Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 100, iss. 3, pp. 335-345, 1956

- Roman Ghirshman, Les fouilles de Tchoga-Zanbil, près de Suse (1956), Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 100, iss. 2, pp. 137-138, 1956

- Roman Ghirshman, VIe campagne de fouilles à Tchoga-Zanbil près de Suse (1956-1957), rapport préliminaire, Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 101, iss. 3, pp. 231-241, 1957

- Roman Ghirshman, FouiIles de Tchoga-Zanbil près de Suse, complexe de quatre temples, Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 103, iss. 1, pp. 74-76, 1959

- Roman Ghirshman, VIIe campagne de fouilles à Tchoga-Zanbil, près de Suse (1958-1959), rapport préliminaire, Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 103, iss. 2, pp. 287-297, 1959

- P. Amiet, Marlik et Tchoga Zanbil, Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 44-47, 1990

External links

- 6,000-Year-Old Ziggurat Found Near Chogha Zanbil In Iran - 2004

- Chogha Zanbil

- World Heritage profile

- Hamid-Reza Hosseini, Shush at the foot of Louvre (Shush dar dāman-e Louvre), in Persian, Jadid Online, 10 March 2009, [1].

Audio slideshow: [2] (6 min 31 sec). - "Struggling to Preserve Tchogha Zanbil". Iranmania.com. November 7, 2005.