Race and intelligence: Difference between revisions

→History of the debate: Rm, this had a citeneeded before my rv to BlackHades' version. |

→Genetic arguments: agree with BlackHades here; this tag not indicated. |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

==Genetic arguments== |

==Genetic arguments== |

||

{{POV-section|date=February 2013}} |

|||

The American Anthropological Association in 1994 stated that intelligence is not biologically determined by race.<ref name="AAA 1994"/> The American Psychological Association in 1994, stated that there is little evidence to support environmental explanations, certainly no support for genetic interpretations, and that presently the cause of the black-white IQ gap is unknown.<ref>{{harvnb|Neisser et al.|1996}}</ref> A number of scientists, however, have concluded sufficient evidence exists to support substantial genetic contribution to explain the black-white IQ gap.<ref name="Rushton & Jensen 2005"/><ref name="Rushton & Jensen 2010"/><ref name="Gottfredson 2007"/><ref>{{harvnb|Herrnstein|Murray|1994}}</ref><ref name="Lynn 2006"/> |

The American Anthropological Association in 1994 stated that intelligence is not biologically determined by race.<ref name="AAA 1994"/> The American Psychological Association in 1994, stated that there is little evidence to support environmental explanations, certainly no support for genetic interpretations, and that presently the cause of the black-white IQ gap is unknown.<ref>{{harvnb|Neisser et al.|1996}}</ref> A number of scientists, however, have concluded sufficient evidence exists to support substantial genetic contribution to explain the black-white IQ gap.<ref name="Rushton & Jensen 2005"/><ref name="Rushton & Jensen 2010"/><ref name="Gottfredson 2007"/><ref>{{harvnb|Herrnstein|Murray|1994}}</ref><ref name="Lynn 2006"/> |

||

Revision as of 21:24, 11 April 2013

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

| Race |

|---|

| History |

| Society |

| Race and... |

| By location |

| Related topics |

The connection between race and intelligence has been a subject of debate in both popular science and academic research since the inception of intelligence quotient (IQ) testing in the early 20th century.[1] There is no widely accepted formal definition of either race or intelligence in academia, nor is there agreement on IQ's validity as a gauge of intelligence.[2] Historically, claims that races differed in intelligence were used to justify colonialism, slavery, Social Darwinism, and eugenics. After losing favor in the postwar period, the idea of racial differences in intelligence was revived by Arthur Jensen in 1969 and drew public attention following the publication of The Bell Curve in 1994. Any discussion of a connection between race and intelligence involves studies from multiple disciplines, including psychology, anthropology, biology and sociology.

Existence of differences in mean IQ scores between racial groups in the United States is well-documented and not subject to much dispute; IQ tests performed in the United States consistently demonstrate variation. These tests show the average IQ scores of East Asian Americans is higher than those of White Americans, and that the average IQ scores of White Americans is higher than those of African Americans. There is no consensus among researchers as to the cause of these group differences.

Both environmental and genetic explanations have been advanced to account for differences in test scores and educational achievement. Systemically disadvantaged minorities perform worse in education and on intelligence tests. Other environmental arguments include differences in health and nutrition (including lead exposure and iodine deficiency), educational quality and test bias.

The American Psychological Association has said that while there are differences in average IQ between racial groups, there is no conclusive evidence for environmental explanations, nor direct empirical support for a genetic interpretation, and that no adequate explanation for differences in group means of IQ scores is currently available.[3][4] The position of the American Anthropological Association is that variation in intelligence cannot be meaningfully explained by dividing a species into biologically-defined races.[5] According to a 1996 statement from the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, although heredity influences behavior in individuals, it does not affect the ability of a population to function in any social setting, all peoples "possess equal biological ability to assimilate any human culture" and "racist political doctrines find no foundation in scientific knowledge concerning modern or past human populations."[6]

History of the debate

This article should include a summary of History of the race and intelligence controversy. (March 2011) |

Claims of races having different intelligence were used to justify colonialism, slavery, social Darwinism, and racial eugenics. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, group differences in intelligence were assumed to be due to race and, apart from intelligence tests, research relied on measurements such as brain size or reaction times. The first IQ test was created between 1905 and 1908 and revised in 1916 (the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales). Alfred Binet, the developer of these tests, warned that these should not be used to measure innate intelligence or to label individuals.[7] However, at the time there was great concern in the United States about the abilities and skills of recent immigrants. Different nationalities were sometimes thought to comprise different races, such as Slavs. The tests were used to evaluate draftees for World War I, and researchers found that people of southern and eastern Europe scored lower than native-born Americans. At the time, such data was used to construct an ethnically based social hierarchy, one in which immigrants were rejected as unfit for service and mentally defective. It was not until later that researchers realized that lower language skills by new English speakers affected their scores on the tests.[8]

In the 1920s, many scientists reacted to eugenicist claims linking abilities and moral character to racial or genetic ancestry. Despite that, states like Virginia enacted laws based in eugenics, such as its 1924 Racial Integrity Act, which established the one-drop rule as law. Generally, understanding grew about the contribution of environment to test-taking and results (such as having English as a second language).[9] By the mid-1930s most US psychologists had adopted the view that environmental and cultural factors played a dominant role. In addition, psychologists were reluctant to risk being associated with the German Nazi claims of a "master race".[10]

In 1969, Arthur Jensen revived the hereditarian point of view in the article, "How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?"[11] It followed changes in public programs introduced to try to correct decades of discrimination against poor African Americans. In 1954, the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that public school segregation was unconstitutional. As part of the Great Society programs under President Lyndon Johnson, the Head Start Program was started with the goal of early intervention to help socially disadvantaged children succeed by providing remedial education. Given the effects of segregation and discrimination into the 1960s, many Head Start programs served African-American children.

Jensen's article questioned remedial education for African-American children; he suggested their poor educational performance reflected an underlying genetic cause rather than lack of stimulation at home.[12] Jensen's work, publicized by the Nobel laureate physicist William Shockley, sparked controversy amongst the academic community and student protests.[13][14]

In their 1988 book The IQ Controversy, the Media, and Public Policy, Mark Snyderman and Stanley Rothman claimed to document a liberal bias in the media coverage of scientific findings regarding IQ. The book builds on the results of a survey of more than 600 psychologists, sociologists and educationalists. 45 percent of those surveyed thought that black-white differences in IQ were the product of both genetic and environmental variation, while 15 percent believed that the differences were entirely due to environmental factors; the rest either declined to answer the question, or thought that there was insufficient evidence to give an answer.[15]

Another debate followed the appearance of The Bell Curve (1994), a book by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, who argued in favor of the hereditarian viewpoint. It provoked the publication of several interdisciplinary books representing the environmental point of view, as well as some in popular science.[16][17] They include The Bell Curve Debate (1995), Inequality by Design: Cracking the Bell Curve Myth (1996) and a second edition of The Mismeasure of Man (1996) by Steven J. Gould.[17] One book written from the hereditarian point of view at this time was The g Factor: The Science of Mental Ability (1998) by Jensen. In 1994 a group of 52 scientists, including leading hereditarians, signed the statement "Mainstream Science on Intelligence". The Bell Curve also led to a 1995 report from the American Psychological Association, "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns", acknowledging a difference between mean IQ scores of whites and blacks as well as the absence of any adequate explanation of it, either environmental or genetic.

The review article "Thirty Years of Research on Race Differences in Cognitive Ability" by Rushton and Jensen was published in 2005.[18] The article was followed by a series of responses, some in support, some critical.[10][19] Richard Nisbett, another psychologist who had also commented at the time, later included an amplified version of his critique as part of the book Intelligence and How to Get It: Why Schools and Cultures Count (2009).[20] Rushton and Jensen in 2010 made a point-for-point reply to this and again summarized the hereditarian position.[21]

Many of the leading hereditarians, mostly psychologists, have received funding from the Pioneer Fund which was headed by Rushton until his death in 2012.[13][17][22][23] The Southern Poverty Law Center lists the Pioneer Fund as a hate group, citing the fund's history, its funding of race and intelligence research, and its connections with racist individuals.[24] On the other hand, Ulrich Neisser writes that "Pioneer has sometimes sponsored useful research—research that otherwise might not have been done at all."[25] Other sources and researches have criticized the Pioneer Fund for promoting scientific racism, eugenics and white supremacy.[13][26][27][28]

Ethics of research

The 1996 report of the APA had comments on the ethics of research on race and intelligence.[1] Gray & Thompson (2004) as well as Hunt & Carlson (2007) have also discussed different possible ethical guidelines.[1][29] Nature in 2009 featured two editorials on the ethics of research in race and intelligence by Steven Rose (against) and Stephen J. Ceci and Wendy M. Williams (for).[30][31]

According to critics, research will run the risk of simply reproducing the horrendous effects of the social ideologies (such as Nazism or social Darwinism) justified in part on claimed hereditary racial differences.[5][32] Steven Rose maintains that the history of eugenics makes this field of research difficult to reconcile with current ethical standards for science.[31]

Linda Gottfredson argues that suggestion of higher ethical standards for research into group differences in intelligence is a double standard applied in order to undermine disliked results.[33] Flynn, a non-hereditarian, has argued that had there been a ban on research on possibly poorly conceived ideas, much valuable research on intelligence testing (including his own discovery of the Flynn effect) would not have occurred.[34]

Validity of "race" and "IQ"

The concept of intelligence and the degree to which it is measurable is and has been a matter of discussion. In Psychology, a psychology textbook by Schacter et al., the argument is made that while there is a general consensus within western science about how to define intelligence, the concept of intelligence as something that can be unequivocally measured by a single figure is not universally accepted.[35] A recurring criticism is that different societies value and promote different kinds of skills and that the concept of intelligence is therefore culturally variable and cannot be measured the same in different societies.[35] Consequently, some critics argue that proposed relationships to other variables are necessarily tentative.[36]

In fields such as psychology, medicine, economics, political science, criminology, and other research on group differences, intelligence is commonly measured using intelligence quotient (IQ) tests.[citation needed] The statement "Mainstream Science on Intelligence" argued that "IQ is strongly related, probably more so than any other single measurable human trait, to many important educational, occupational, economic, and social outcomes ... Whatever IQ tests measure, it is of great practical and social importance". Most of the research on intelligence differences between racial groups is based on IQ testing. These tests are highly correlated with the psychometric variable g (for general intelligence factor). Other tests that are also highly correlated with g are also seen as measures of cognitive ability and have sometimes been used in the research. US examples include the Armed Forces Qualifying Test; SAT; GRE; GMAT; and LSAT. International student assessment tests that have been used include the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, Programme for International Student Assessment, and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study.

The concept of race as a meaningful category of analysis is also hotly contested. The authors of two articles in two encyclopedias, the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity and Society, argue that today the mainstream view is that race is a social construction that is based not mainly in actual biological differences but rather on folk ideologies that construct groups based on social disparities and superficial physical characteristics.[37][38] Sternberg, Grigorenko & Kidd (2005) state that the overwhelming portion of the literature correlating race with identity has tacitly adopted folk definitions of race.[36] The American Anthropological Association in 1998 published a "Statement on 'Race'" which rejected the existence of "races" as unambiguous, clearly demarcated, biologically distinct groups.[32] Others argue that this view is restricted to certain fields, while in other fields, race is still seen as a valid biological category.[39]

Race in the studies is almost always determined using self-reports, rather than based on analyses of the genetic history of the tested individuals. According to psychologist David Rowe, self-report is the preferred method for racial classification in studies of racial differences because classification based on genetic markers alone ignore the "cultural, behavioral, sociological, psychological, and epidemiological variables" that distinguish racial groups.[40] Hunt and Carlson write that "Nevertheless, self-identification is a surprisingly reliable guide to genetic composition. Tang et al. (2005) applied mathematical clustering techniques to sort genomic markers for over 3,600 people in the United States and Taiwan into four groups. There was almost perfect agreement between cluster assignment and individuals' self-reports of racial/ethnic identification as white, black, East Asian, or Latino."[1]

The notions that cluster analysis and the correlation between self-reported race and genetic ancestry support a view of race as primarily based in biology is contradicted by most anthropologists. For example, C. Loring Brace[41] and geneticist Joseph Graves,[42] have argued that while it is certainly possible to find biological and genetic variation that corresponds roughly to the groupings normally defined as races, this is true for almost all geographically distinct populations. The cluster structure of the genetic data is dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the populations sampled. When one samples continental groups, the clusters become continental; if one had chosen other sampling patterns, the clusters would be different. Kaplan 2011 therefore concludes that while racial groups are characterized by different allele frequencies, this does not mean that racial classification is a natural taxonomy of the human species, because multiple other genetic patterns can be found in human populations that crosscut racial distinctions. In this view, racial groupings are social constructs that have also a biological reality which is largely an artifact of how the category has been constructed.

Earl Hunt agrees that racial categories are defined by social conventions, though he points out that they also correlate with clusters of both genetic traits and cultural traits. Hunt explains that, due to this, racial IQ differences are caused by these variables that correlate with race, and race itself is rarely a causal variable. Researchers who study racial disparities in test scores are studying the relationship between the scores and the many race-related factors which could potentially affect performance. These factors include health, wealth, biological differences, and education.[43]

Group differences

Earl Hunt and Jerry Carlson outlined four contemporary position on differences in IQ based on race or ethnicity. The first is that these reflect real differences in average group intelligence, which is caused by a combination of environmental factors and heritable differences in brain function. A second position is that differences in average cognitive ability between races exist and are caused entirely by social and/or environmental factors. A third position holds that differences in average cognitive ability between races do not exist, and that the differences in average test scores are the result of inappropriate use of the tests themselves. Finally, a fourth position is that either or both of the concepts of race and general intelligence are poorly constructed and therefore any comparisons between races are meaningless.[1]

US test scores

Rushton & Jensen (2005) write that, in the United States, self-identified blacks and whites have been the subjects of the greatest number of studies. They state that the black-white IQ difference is about 15 to 18 points or 1 to 1.1 standard deviations (SDs), which implies that between 11 and 16 percent of the black population have an IQ above 100 (the white mean). The black-white IQ difference is largest on those components of IQ tests that best represent the general intelligence factor g.[18] The 1996 APA report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" and the 1994 editorial statement "Mainstream Science on Intelligence" gave more or less similar estimates.[4][44] Roth et al. (2001), in a review of the results of a total of 6,246,729 participants on other tests of cognitive ability or aptitude, found a difference in mean IQ scores between blacks and whites of 1.1 SD. Consistent results were found for college and university application tests such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (N = 2.4 million) and Graduate Record Examination (N = 2.3 million), as well as for tests of job applicants in corporate sections (N = 0.5 million) and in the military (N = 0.4 million).[45]

A 2006 study by Dickens and Flynn estimated that the difference between mean scores of blacks and whites closed by about 5 or 6 IQ points between 1972 and 2002,[46] which would be a reduction of about one-third. However this was challenged by Rushton & Jensen who claim the difference remains stable.[47] In a 2006 study, Murray agreed with Dickens and Flynn that there has been a narrowing of the difference; "Dickens' and Flynn's estimate of 3–6 IQ points from a base of about 16–18 points is a useful, though provisional, starting point". But he argued that this has stalled and that there has been no further narrowing for people born after the late 1970s.[48] Murray found similar results in a 2007 study.[49]

The IQ distributions of other racial and ethnic groups in the United States are less well-studied. The Bell Curve (1994) stated that the average IQ of African Americans was 85, Latinos 89, whites 103, East Asians 106, and Jews 113. Asians score relatively higher on visuospatial than on verbal subtests. The few Amerindian populations who have been systematically tested, including Arctic Natives, tend to score worse on average than white populations but better on average than black populations.[45]

According to several studies, Ashkenazi Jews score 0.75 to 1.0 standard deviations above the general European average. This corresponds to an IQ of 112–115. Other studies have found somewhat lower values. During the 20th century, this population made up about 3% of the total US population, but won 27% of the US science Nobel Prizes and 25% of the Turing Awards. They have high verbal and mathematical scores, while their visuospatial abilities are typically somewhat lower, by about one half standard deviation, than the European average.[50] See also Ashkenazi Jewish intelligence.

The racial groups studied in the United States and Europe are not necessarily representative samples for populations in other parts of the world. Cultural differences may also factor in IQ test performance and outcomes. Therefore, results in the United States and Europe do not necessarily correlate to results in other populations.[51]

International comparisons

The validity and reliability of IQ scores obtained from outside of the United States and Europe have been questioned due to the possibility of test bias as discussed in a later section. Nevertheless, some researchers have attempted to measure IQ variation in a global context.

Flynn effect

Raw scores on IQ tests have been rising. This score increase, primarily in the lower end of the distribution, is known as the "Flynn effect," named for James R. Flynn, who did much to document it and promote awareness of its implications. In the United States, the increase has been continuous and approximately linear from the earliest years of testing to the present. For example, in the United States the average scores of blacks on some IQ tests in 1995 were the same as the scores of whites in 1945.[52]

Potential environmental causes

The following environmental factors are some of those suggested as explaining a portion of the differences in average IQ between races. These factors are not mutually exclusive with one another, and some may in fact contribute directly to others. Furthermore, the relationship between genetics and environmental factors may be complicated. For example, the differences in socioeconomic environment for a child may be due to differences in genetic IQ for the parents,[4] and the differences in average brain size between races could be the result of nutritional factors.[53]

Test bias

Studies on other groups and in other nations have argued that IQ tests may be biased against certain groups.[54][55][56][57] The validity and reliability of IQ scores obtained from outside the United States and Europe have been questioned, in part because of the inherent difficulty of comparing IQ scores between cultures.[58][59] Several researchers have argued that cultural differences limit the appropriateness of standard IQ tests in non-industrialized communities.[60][61] In the mid-1970s, for example, the Soviet psychologist Alexander Luria concluded that it was impossible to devise an IQ test to assess peasant communities in Russia because taxonomy was alien to their way of reasoning.[62]

A 1996 report by the American Psychological Association states that controlled studies show that differences in mean IQ scores were not substantially due to bias in the content or administration of the IQ tests. Furthermore, the tests are equally valid predictors of future achievement for black and white Americans.[4] This view is reinforced by Nicholas Mackintosh in his 1998 book IQ and Human Intelligence,[63] and by a 1999 literature review by Brown, Reynolds & Whitaker (1999).[64]

Stereotype threat

Stereotype threat is the fear that one's behavior will confirm an existing stereotype of a group with which one identifies or by which one is defined; this fear may in turn lead to an impairment of performance.[65] Testing situations that highlight the fact that intelligence is being measured tend to lower the scores of individuals from racial-ethnic groups who already score lower on average or are expected to score lower. Stereotype threat conditions cause larger than expected IQ differences among groups.

Socioeconomic environment

According to the report of a 1996 APA task force, socioeconomic status (SES) cannot account for all the observed racial-ethnic group differences in IQ in the US. Their first reason for this conclusion is that the difference between mean test scores of blacks and whites is not eliminated when individuals and groups are matched on SES. Second, excluding extreme conditions, nutritional and biological factors that may vary with SES have shown little effect on IQ. Third, the relationship between IQ and SES is not simply one in which SES determines IQ, but differences in intelligence, particularly parental intelligence, also cause differences in SES, making separating the two factors difficult.[4]

Health and nutrition

Environmental factors including lead exposure,[66] breast feeding,[68] and nutrition[69][70] can significantly affect cognitive development and functioning. For example, iodine deficiency causes a fall, on average, of 12 IQ points.[71] Such impairments may sometimes be permanent, sometimes be partially or wholly compensated for by later growth. The first two years of life is the critical time for malnutrition, the consequences of which are often irreversible and include poor cognitive development, educability, and future economic productivity.[72] The African American population of the United States is statistically more likely to be exposed to many detrimental environmental factors such as poorer neighborhoods, schools, nutrition, and prenatal and postnatal health care.[73][74]

The Copenhagen consensus in 2004 stated that lack of both iodine and iron has been implicated in impaired brain development, and this can affect enormous numbers of people: it is estimated that one-third of the total global population are affected by iodine deficiency. In developing countries, it is estimated that 40% of children aged four and under suffer from anaemia because of insufficient iron in their diets.[75]

Eppig, Fincher & Thornhill (2010) argue that "From an energetics standpoint, a developing human will have difficulty building a brain and fighting off infectious diseases at the same time, as both are very metabolically costly tasks" and that differences in prevalence of infectious diseases (such as malaria) may be an important explanation for differences in IQ between different regions of the world.[76] They tested other hypotheses as well, including genetic explanations, concluding that infectious disease was "the best predictor".[77] Christopher Hassall and Thomas Sherratt repeated the analysis, and concluded "that infectious disease may be the only really important predictor of average national IQ".[77]

In order to mitigate the effects of education on IQ, Eppig, Fincher & Thornhill (2010) repeated their analysis across the United States where standardized and compulsory education exists.[77] The correlation between infectious disease and average IQ was confirmed, and they concluded that the "evidence suggests that infectious disease is a primary cause of the global variation in human intelligence".[77]

Education

Several studies have proposed that a large part of the gap can be attributed to differences in quality of education.[78] Racial discrimination in education has been proposed as one possible cause of differences in educational quality between races.[79] According to a paper by Hala Elhoweris, Kagendo Mutua, Negmeldin Alsheikh and Pauline Holloway, teachers' referral decisions for students to participate in gifted and talented educational programs were influenced in part by the students' ethnicity.[80]

The Abecedarian Early Intervention Project, an intensive early childhood education project, was also able to bring about an average IQ gain of 4.4 points at age 21 in the black children who participated in it compared to controls.[68] Arthur Jensen agreed that the Abecedarian project demonstrates that education can have a significant effect on IQ, but also said that no educational program thus far has been able to reduce the black-white IQ gap by more than a third, and that differences in education are thus unlikely to be its only cause.[81]

Rushton and Jensen argue that long-term follow-up of the Head Start Program found large immediate gains for blacks and whites but that these were quickly lost for the blacks although some remained for whites. They argue that also other more intensive and prolonged educational interventions have not produced lasting effects on IQ or scholastic performance.[18] Nisbett argues that they ignore studies such as Campbell & Ramey (1994) which found that at the age 12, 87% black of infants exposed to an intervention had IQs in the normal range (above 85) compared to 56% of controls, and none of the intervention-exposed children were mildly retarded compared to 7% of controls. Other early intervention programs have shown IQ effects in the range of 4–5 points, which are sustained until at least age 8–15. Effects on academic achievement can also be substantial. Nisbett also argues that not only early age intervention can be effective, citing other successful intervention studies from infancy to college.[82]

Logographic writing system

Complex logographic writing systems have been proposed as an explanation for the higher visuospatial IQ scores of East Asians. Critics argue that the causation may be reversed with higher visuospatial ability causing the development of pictorial symbols in writing rather than alphabetic ones. Another argument is that East Asians adopted at birth also score high on IQ tests. Similar relatively higher visuospatial abilities are also found among Inuit and Native Americans, whose ancestors migrated from East Asia to the Americas.[83][84]

Caste-like minorities

A large number of studies have shown that systemically disadvantaged minorities, such as the African American minority of the United States generally perform worse in the educational system and in intelligence tests than the majority groups or less disadvantaged minorities such as immigrant or "voluntary" minorities.[4] The explanation of these findings may be that children of caste-like minorities, due to the systemic limitations of their prospects of social advancement, do not have "effort optimism", i.e. they do not have the confidence that acquiring the skills valued by majority society, such as those skills measured by IQ tests, is worthwhile. They may even deliberately reject certain behaviors seen as "acting white".[4][85][86][87]

This argument is also explored in the book Inequality by Design: Cracking the Bell Curve Myth (1996) which argues that it is not lower average intelligence that leads to the lower status of racial and ethnic minorities, it is instead their lower status that leads to their lower average intelligence test scores. One example being Jews in the early 20th century in the US who, the authors argue, scored low on IQ tests. To substantiate this claim, the book presents a table comparing social status or caste position with test scores and measures of school success in several countries around the world. Examples include Koreans, Peruvians and Brazilians in Japan, Burakumin in Japan, Australian Aborigines, Romani in Czechoslovakia, Maori in New Zealand, Afro-Brazilians, Indigenous Brazilians, Pardos and Rural Exiles (as, but not limited to, people from Northeast in Brasília, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro metropolitan areas, and including a minority of European descent) in Brazil, Afrikaners in South Africa, Catholics in North Ireland, Irish and Scottish in Great Britain, Arabs and Sephardi Jews in Israel, and Dalit, low caste, and tribal people in India. The authors note, however, that the comparisons made in the table do not represent the results of all relevant findings, that sometimes studies have shown more mixed findings, that the tests and procedures varied greatly from study to study, and that there is no simple way to compare the size of group differences. The statement regarding Arabs in Israel, for example, is based on a news report that, in 1992, 26% of Jewish high school, predominantly Ashkenazim, students passed their matriculation exam as opposed to 15% of Arab students.[88] Stephen Jay Gould in the The Mismeasure of Man also argued that Jews in the early 20th century scored low on IQ tests. Rushton as well as Cochran, Hardy & Harpending have argued that this is a misrepresentation of the studies and that also the early testing support a high average Jewish IQ.[50][89]

Murray replies that purely sociocultural factors like this cannot explain the gap, because the size of the gap on any test is dependent on that test's degree of g-loading. As an example, Murray notes that the test of reciting a string of digits backwards is much more g-loaded than reciting it forwards, and the black-white gap is around twice as large on the first test as on the second. According to Murray, there is no way that culture or motivation could systematically encourage black performance on one test while decreasing it on another, when both tests are provided by the same examiner in the same setting.[90]

Cultural traditions valuing education

Nisbett argues cultural traditions valuing education can explain the high results in the US for Ashkenazi Jews (Talmud scholarship) and East Asians (Confucianism and the Imperial examination system).[91]

Black subculture

JR Harris suggested in The Nurture Assumption that different peer group cultures may contribute to the black-white IQ gap. She cites the work of Thomas Kindermann, whose longitudinal studies find that peer groups significantly affect scholastic achievement.[92]

Genetic arguments

The American Anthropological Association in 1994 stated that intelligence is not biologically determined by race.[5] The American Psychological Association in 1994, stated that there is little evidence to support environmental explanations, certainly no support for genetic interpretations, and that presently the cause of the black-white IQ gap is unknown.[93] A number of scientists, however, have concluded sufficient evidence exists to support substantial genetic contribution to explain the black-white IQ gap.[18][21][33][94][95]

Genetics of race and intelligence

The decoding of the human genome has enabled scientists to search for sections of the genome that contribute to cognitive abilities, and there are also ways to study whether the differences in frequency of particular genetic variants between populations contribute to differences in average cognitive abilities.

Templeton has stated that an FST of at least 25%-30% is a standard criterion for the identification of a subspecies. Based on (Barbujani et al 1997), he states that most genetic diversity in humans exists as differences among individuals within populations and that only an FST of 15.6% can be used to genetically differentiate the major human “races”. Short of the required 25%-30%, he concludes human races does not exist under the traditional concept of subspecies.[96] Still, although 15.6% is a modest figure, Templeton states it can still have evolutionary and genetic significance and therefore the evolutionary significance of genetic differentiation among human populations is a legitimate issue.[97]

Intelligence is both a quantitative and polygenic trait. This means that intelligence is under the influence of several genes, possibly several thousand. The effect of most individual genetic variants on intelligence is thought to be very small, well below 1% of the variance in g. Current studies using quantitative trait loci have yielded little success in the search for genes influencing intelligence. Robert Plomin is confident that QTLs responsible for the variation in IQ scores exist, but due to their small effect sizes, more powerful tools of analysis will be required to detect them.[98] Others assert that no useful answers can be reasonably expected from such research before an understanding of the relation between DNA and human phenotypes emerges.[74]

A 2005 literature review article on the links between race and intelligence in American Psychologist stated that no gene has been shown to be linked to intelligence, "so attempts to provide a compelling genetic link of race to intelligence are not feasible at this time".[99] Several candidate genes have been proposed to have a relationship with intelligence.[100][101] However, a review of candidate genes for intelligence published in Deary, Johnson & Houlihan (2009) failed to find evidence of an association between these genes and general intelligence, stating "there is still almost no replicated evidence concerning the individual genes, which have variants that contribute to intelligence differences".[102]

Heritability within and between groups

Heritability is defined as the proportion of interindividual variance in a trait which is attributable to genotype within a defined population in a specific environment. A heritability of 1 indicates that variation correlates fully with genetic variation and a heritability of 0 indicates that there is no correlation between the trait and genes at all. There is broad agreement that individual variation in intelligence is neither fully genetic nor fully environmental, but there is little agreement on the relative contribution of genes and environment on individual intelligence.

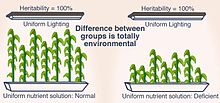

It has been argued that intelligence is substantially heritable within populations, with 30–50% of variance in IQ scores in early childhood being attributable to genetic factors in analyzed US populations, increasing to 75–80% by late adolescence.[4][102] High heritability does not imply that a trait is genetic or unchangeable, however, as environmental factors that affect all group members equally will not be measured by heritability (see the figure) and the heritability of a trait may also change over time in response to changes in the distribution of genes and environmental factors.[4] High heritability also doesn't imply that all of the heritability is genetically determined, but can also be due to environmental differences that affect only a certain genetically defined group (indirect heritability).[103]

Jensen and Rushton have argued that there may be environmental factors ("X factors") that are not measured by the heritability figure, but such factors must have the properties of not affecting whites while at the same time affecting all blacks equally, but, the hereditarians argue, no such plausible factors have been found and other statistical tests for the presence of such an influence in the US are negative.[21][104]

Dickens and Flynn argue that the conventional interpretation ignores the role of feedback between factors, such as those with a small initial IQ advantage, genetic or environmental, seeking out more stimulating environments which will gradually greatly increase their advantage, which, as one consequence in their alternative model, would mean that the "heritability" figure is only in part due to direct effects of genotype on IQ.[1][105][106]

Spearman's hypothesis

Spearman's hypothesis states that the magnitude of the black-white difference in tests of cognitive ability is entirely or mainly a function of the extent to which a test measures general mental ability, or g. The hypothesis, first formalized by Arthur Jensen in the 1980s based on Charles Spearman's earlier comments on the topic, argues that differences in g are the sole or major source of differences between blacks and whites observed in many studies of race and intelligence. Various criticisms have been advanced and the validity of the arguments remain unresolved.

Regression toward the mean

This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (December 2011) |

Jensen and Rushton argue that regression toward the mean effects observed in studies comparing blacks and whites with high and low IQs to the IQs of their close relatives provide evidence of a polygenetic basis for the black/white IQ gap.[107][108] However, other researchers have found Jensen's arguments to be unpersuasive,[109] noting that regression to the mean is merely a statistical artifact and cannot be used to isolate potential causal factors.[110]

Gradual gap appearance

Fryer & Levitt (2006) found in tests of children aged eight to twelve months only minor differences (0.06 SD) between blacks and whites that disappeared with the inclusion of a limited set of controls including social-economic status.[111] Flynn has argued that the U.S. black-white gap appears gradually which suggests environmental causes. "At just 10 months old, the average score is only one point behind; by the age of 4, it is 4.6 points behind, and by the age of 24, the gap is 16.6 points. This could be due to genes, but the steady rate after the age of 4 (about 0.6 IQ points lost every year) suggests otherwise, since genetically driven differences such as height differences between males and females tend to kick in at a certain age."[112]

Rushton and Jensen argue that the black-white IQ difference of one standard deviation is present at the age of 3 and does not change significantly afterward.[18] Murray, also a hereditarian, argues that the heritability of IQ increases with age which is reflected in the racial IQ gaps gradually increasing.[90]

Adoption studies

Several studies have been done on the effect of similar rearing conditions on children from different races.

The Minnesota Transracial Adoption Study (1976) examined the IQ test scores of 122 adopted children and 143 nonadopted children reared by advantaged white families. The children were restudied ten years later.[113][114] The study found higher IQ for whites compared to blacks, both at age 7 and age 17.[113][115]

Three other studies found opposing evidence with none finding higher intelligence in white children than in black children. However, unlike the Minnesota Transracial Adoption Study, these studies did not retest the children post-adolescence when heritability of IQ would be much higher.[18][21][116]

Moore (1986) compared black and mixed-race children adopted by either black or white middle-class families in the US. Moore observed that 23 black and interracial children raised by white parents had a significantly higher mean score than 23 age-matched children raised by black parents (117 vs 104), and argued that differences in early socialization explained these differences.

Eyferth (1961) studied the out-of-wedlock children of black and white soldiers stationed in Germany after World War 2 and then raised by white German mothers and found no significant differences.

Tizard et al. (1972) studied black (African and West Indian), white, and mixed-race children raised in British long-stay residential nurseries. Three out of four tests found no significant differences. One test found higher scores for non-whites.[117]

The data is summarized below:

| Biological parents | Number of children | Average IQ | Raised by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota Transracial Adoption Study (1976) United States | |||

| Black | 21 | 95/89 | White non-biological couple |

| Black-white | 55 | 110/99 | White non-biological couple |

| White | 16 | 118/106 | White non-biological couple |

| Asian or Amerindian | 12 | 101/99 | White non-biological couple |

| White | 104 | 116/109 | White biological couple |

| Moore (1986) United States | |||

| Black | 17 | 102.9 | Black non-biological couple |

| Black-white | 6 | 105.7 | Black non-biological couple |

| Black | 9 | 118.0 | White non-biological couple |

| Black-white | 14 | 116.5 | White non-biological couple |

| Eyferth (1961) Germany | |||

| Black-white | 98 | 96.5 | White biological single mother |

| White | 83 | 97.2 | White biological single mother |

| Tizard et al. (1972) United Kingdom | |||

| Black | 15 | 105.7 | Long-stay residential nurseries |

| Black-white | 15 | 109.8 | Long-stay residential nurseries |

| White | 25 | 101.3 | Long-stay residential nurseries |

Studies on Korean infants adopted by European families have consistently shown a higher IQ than the European average.[18][95][118][119]

Frydman and Lynn (1989) showed a mean IQ of 119 for Korean infants adopted by Belgium families. After correcting for the Flynn effect, the IQ of the adopted Korean children was still 10 points higher than the indigenous Belgian children.[18][95][118]

Stams et al. (2000) showed a mean IQ of 115 for Korean infants adopted in the Netherlands.[119]

Lindblad et al. (2009) studied school performance of adoptees in Sweden relative to intelligence tests in Sweden's military. The study showed that Korean adoptees had a higher grade point average and higher intelligence test score than Sweden's national average. While non-Korean adoptees had a lower grade point average and lower intelligence test score than Sweden's national average.[120]

| Biological parents | Number of children | Average IQ | Raised by | Nutritional status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winick, Meyer, and Harris (1975) United States | ||||

| Korean | 37 | 102 | White non-biological couple | Severely malnourished |

| Korean | 38 | 106 | White non-biological couple | Poorly nourished |

| Korean | 37 | 112 | White non-biological couple | Well nourished |

| Frydman and Lynn (1989) harvtxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFrydman_and_Lynn1989 (help) Belgium | ||||

| Korean | 19 | 119 | White non-biological couple | |

| Stams et al. (2000) Netherlands | ||||

| Korean | 36 | 115 | White non-biological couple | |

Racial admixture studies

Many people have an ancestry from different geographic regions. For example, African Americans typically have ancestors from both Africa and Europe, with, on average, 20% of their genome inherited from European ancestors.[121] If racial IQ gaps have a partially genetic basis, blacks with a higher degree of European ancestry should on average have higher IQ, because the genes inherited from European ancestors would likely include some genes with a positive effect on IQ.[122]

Witty and Jenkins (1936) compared a group of 63 black students all with an IQ of 125 and above and compared their white ancestry level to Herskovits (1930) national sample of blacks and concluded no significant difference in the level of white ancestry between their sample of gifted students and the national sample of Herskovits (1930).[123][124]

This study has been criticized as the study's control sample of Herskovitz (1930) was not considered representative. 50% of the Herskovitz (1930) sample were composed of Howard University undergraduates and “well to do” professions with higher than average SES.[125] Blacks in both the control sample of Herskovitz (1930) and the test sample by Witty and Jenkins (1936) had higher percentage of white ancestry (approximately 30%) than the national average.[126]

Shuey (1966) summarized 18 black-white admixture studies and concluded 16 out of 18 studies showed a positive correlation between lighter skin color and higher IQ with correlation ranging from 0.12 to 0.30.[127][128][129] Nisbett and Jensen have both argued that skin color is a highly imprecise measure of racial ancestry.[130]

The frequency of different blood types vary with ancestry. Correlations between degree of European blood types and IQ have varied between 0.05 and -0.38 in two studies from 1973 and 1977. Nisbett writes that one problem with these studies is that white blood genes are very weakly associated with one another in the black population, so they are not a reliable method of estimating ancestry.[131] T. Edward Reed, an expert on blood groups, argues that the methodology used in these studies would have been unable to detect any difference, regardless of whether or not the hereditarian hypothesis is correct.[132]

Some authors have suggested that new studies of the relationship ancestry and IQ should be performed using modern DNA-based ancestry estimations, which would provide a more reliable measure of ancestry than is possible based on skin tone or blood groups.[40][133]

Mental chronometry

Mental chronometry is an area of research which measures the elapsed time between the presentation of a sensory stimulus and the subsequent behavioral response by the participant. This time is known as reaction time (RT), and is considered a measure of the speed and efficiency with which the brain processes information.[134] Scores on most types of RT tasks tend to correlate with scores on standard IQ tests as well as with g, and no relationship has been found between RT and any other psychometric factors independent of g.[134] The strength of the correlation with IQ varies from one RT test to another, but Hans Eysenck gives 0.40 as a typical correlation under favorable conditions.[135] According to Jensen individual differences in RT have a substantial genetic component, and heritability is higher for performance on tests that correlate more strongly with IQ.[104] Nisbett argues that some studies have found correlations closer to 0.2, and that the correlation is not always found.[136]

Several studies have found differences between races in average reaction times. These studies have generally found that reaction times among black, Asian and white children follow the same pattern as IQ scores.[137][138][139] Rushton and Jensen have argued that reaction time is independent of culture and that the existence of race differences in average reaction time is evidence that the cause of racial IQ gaps is partially genetic instead of entirely cultural.[18] Responding to this argument in Intelligence and How to Get It, Nisbett has pointed to the Jensen & Whang (1993) study in which a group of Chinese Americans had longer reaction times than a group of European Americans, despite having higher IQs. Nisbett also mentions findings in Flynn (1991) and Deary (2001) suggesting that movement time (the measure of how long it takes a person to move a finger after making the decision to do so) correlates with IQ just as strongly as reaction time does, and that average movement time is faster for blacks than for whites.[140]

Policy relevance

Jensen and Rushton argue that the existence of biological group differences does not rule out, but raises questions about the worthiness of policies such as affirmative action or placing a premium on diversity. They also argue for the importance of teaching people not to overgeneralize or stereotype individuals based on average group differences, because of the significant overlap of people with varying intelligence between different races.[18]

The environmentalist viewpoint argues for increased interventions in order to close the gaps.[citation needed] Nisbett argues that schools can be greatly improved and that many interventions at every age level are possible.[141] Flynn, arguing for the importance of the black subculture, writes that "America will have to address all the aspects of black experience that are disadvantageous, beginning with the regeneration of inner city neighbourhoods and their schools. A resident police office and teacher in every apartment block would be a good start."[112] Researchers from both sides agree that interventions should be better researched.[136][21]

Especially in developing nations society has been urged to take on the prevention of cognitive impairment in children as of the highest priority. Possible preventable causes include malnutrition, infectious diseases such as meningitis, parasites, and cerebral malaria, in utero drug and alcohol exposure, newborn asphyxia, low birth weight, head injuries, and endocrine disorders.[142]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Hunt & Carlson 2007

- ^ Sternberg, Robert J. (2011). The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. p. 295. ISBN 9780521518062.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schacter, Gilbert & Wegner 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Neisser et al. 1996 "The differential between the mean intelligence test scores of blacks and whites (about one standard deviation, although it may be diminishing) does not result from any obvious biases in test construction and administration, nor does it simply reflect differences in socio-economic status. Explanations based on factors of caste and culture may be appropriate, but so far have little direct empirical support. There is certainly no such support for a genetic interpretation. At present, no one knows what causes this differential." Cite error: The named reference "Neisser et al. 1996" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c AAA 1994 Cite error: The named reference "AAA 1994" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ AAPA 1996

- ^ Plotnik & Kouyoumdjian 2011

- ^ Gould 1981

- ^ Pickren & Rutherford 2010, p. 163

- ^ a b Ludy 2006

- ^ Jensen 1969, p. 82

- ^ Alland 2002, pp. 79–80

- ^ a b c Tucker 2002

- ^ Wooldridge 1995

- ^ Snyderman & Rothman 1987, pp. 137–144

- ^ Mackintosh 1998

- ^ a b c Maltby, Day & Macaskill 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rushton & Jensen 2005

- ^ Rouvroy 2008, p. 86

- ^ Nisbett 2009, pp. 209–36

- ^ a b c d e f Rushton & Jensen 2010

- ^ Graves 2002a

- ^ Grossman & Kaufman 2001

- ^ Berlet 2003

- ^ Neisser 2004

- ^ Pioneer Fund Board

- ^ Falk 2008, p. 18

- ^ Wroe 2008, p. 81

- ^ Gray & Thompson 2004

- ^ Ceci & Williams 2009

- ^ a b Rose 2009, pp. 786–88

- ^ a b AAA 1998

- ^ a b Gottfredson 2007

- ^ Flynn 2009

- ^ a b Schacter, Gilbert & Wegner 2007, pp. 350–1

- ^ a b Sternberg, Grigorenko & Kidd 2005

- ^ Britannica 2012

- ^ Schaefer 2008

- ^ Kaszycka, Štrkalj & Strzałko 2009

- ^ a b Rowe 2005

- ^ Brace 2005

- ^ Graves 2001

- ^ Hunt 2010, pp. 408–10

- ^ Gottfredson 1997

- ^ a b Roth et al. 2001

- ^ Dickens & Flynn 2006

- ^ Rushton & Jensen 2006

- ^ Murray 2006

- ^ Murray 2007

- ^ a b Cochran, Hardy & Harpending 2006

- ^ Niu & Brass 2011

- ^ Mackintosh 1998, p. 162

- ^ Neisser 1997

- ^ Cronshaw et al. 2006, p. 278

- ^ Verney et al. 2005

- ^ Borsboom 2006

- ^ Shuttleworth-Edwards et al. 2004

- ^ Richardson 2004

- ^ Hunt & Wittmann 2008

- ^ Irvine 1983

- ^ Irvine & Berry 1988 a collection of articles by several authors discussing the limits of assessment by intelligence tests in different communities in the world. In particular, Reuning (1988) describes the difficulties in devising and administering tests for Kalahari bushmen.

- ^ Mackintosh 1998, pp. 180–2

- ^ Mackintosh 1998, p. 174: "Despite widespread belief to the contrary, however, there is ample evidence, both in Britain and the USA, that IQ tests predict educational attaintment just about as well in ethnic minorities as in the white majority."

- ^ Brown, Reynolds & Whitaker 1999

- ^ Aronson, Wilson & Akert 2005

- ^ a b Bellinger, Stiles & Needleman 1992

- ^ MMWR 2005

- ^ a b Campbell et al. 2002

- ^ Ivanovic et al. 2004

- ^ Saloojee & Pettifor 2001

- ^ Qian et al. 2005

- ^ The Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Undernutrition, 2008.

- ^ Nisbett 2009, p. 101

- ^ a b Cooper 2005

- ^ Behrman, Alderman & Hoddinott 2004

- ^ Eppig, Fincher & Thornhill 2010

- ^ a b c d Eppig 2011

- ^ Manly et al. 2002 and Manly et al. 2004

- ^ Mickelson 2003

- ^ Elhoweris et al. 2005

- ^ Miele 2002, p. 133

- ^ Nisbett 2005, pp. 303–4

- ^ Demetriou et al. 2005

- ^ Bower 2005

- ^ Ogbu 1978

- ^ Ogbu 1994

- ^ Goleman 1988

- ^ Fischer et al. 1996, pp. 191–2

- ^ Rushton 1997b, pp. 169–80

- ^ a b Murray 2005

- ^ Nisbett 2009, pp. 158–9

- ^ Kindermann 1993

- ^ Neisser et al. 1996

- ^ Herrnstein & Murray 1994

- ^ a b c Lynn, Richard (2006) Race Differences in Intelligence

- ^ Templeton, Alan R. (1999). "Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 100 (3): 632–650.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Templeton, Alan R. (2003). "Human Races in the Context of Recent Human Evolution: A Molecular Genetic Perspective". In Goodman, Alan H.; Heath, Deborah; Lindee, M. Susan (eds.). Genetic nature/culture: anthropology and science beyond the two-culture divide. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 234–257. ISBN 0-520-23792-7. “These modest genetic differences can still have evolutionary and genetic significance. Therefore, the evolutionary significance of genetic differentiation among human populations (not races, since none exist) is a legitimate issue.” pg 248

- ^ Plomin, Kennedy & Craig 2005, p. 513

- ^ Sternberg, Grigorenko & Kidd 2005, p. 46

- ^ Zinkstok et al. 2007

- ^ Dick et al. 2007

- ^ a b Deary, Johnson & Houlihan 2009

- ^ a b Block 2002

- ^ a b Jensen 1998

- ^ Nisbett 2009, p. 212

- ^ Dickens & Flynn 2001

- ^ Jensen 1973, pp. 107–9

- ^ Rushton 2003

- ^ Flynn 2010, pp. 363–6

- ^ See:

- ^ Fryer & Levitt 2006

- ^ a b Flynn 2008

- ^ a b Weinberg, Scarr & Waldman 1992

- ^ Loehlin 2000, p. 185

- ^ Scarr, S., & Weinberg, R. A. (1976). IQ test performance of black children adopted by White families. American Psychologist, 31, 726-739.

- ^ Nyborg, Helmuth (2003). The Scientific Study of General Intelligence: Tribute to Arthur Jensen. Elsevier Science. pp. 402–406. ISBN 978-0080437934.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Tizard et al. 1972

- ^ a b Frydman and Lynn (1989). "The intelligence of Korean children adopted in Belgium". Personality and Individual Differences. 10 (12): 1323–1325.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Stams, Juffer, Rispens, Hoksbergen (2000). "The development and adjustment of 7-year-old children adopted in infancy". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 41 (8): 1025–1037.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lindblad; et al. (2009). "School performance of international adoptees better than expected from cognitive test results" (PDF). "European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 18 (5): 301–308.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bryc et al. 2009

- ^ Loehlin 2000

- ^ Witty and Jenkins (1936). "A Socio-Psychological Study of Negro Children of Superior Intelligene". Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 1: 179–192.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Jenkins (1936). "Intra-race testing and negro intelligence" (PDF). Journal of Negro Education. 5 (2): 175–190.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Mackenzie, Brian (1984). "Explaining Race Differences in IQ" (PDF). American Psychologist. 39 (11): 1214–1233.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Loehlin, John (1975). Race Differences in Intelligence. W H Freeman & Co. ISBN 978-0716707530.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Shuey, Audrey (1966). The testing of Negro intelligence. Social Science Press. pp. 456–463. ISBN 9780911396003.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Jensen, Arthur (2012). Educability and Group Differences. Routledge. pp. 222–224. ISBN 9780415678568.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Nyborg, Helmuth (2003). The Scientific Study of General Intelligence: Tribute to Arthur Jensen. Elsevier Science. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0080437934.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Nisbett 2009, p. 227

- ^ Nisbett 2009, p. 228

- ^ Reed 1997, pp. 77–8

- ^ Lee 2010

- ^ a b Jensen 2006

- ^ Eysenck 1987

- ^ a b Nisbett 2009

- ^ Lynn & Vanhanen 2002

- ^ Jensen & Whang 1993

- ^ Pesta & Poznanski 2008

- ^ Nisbett 2009, pp. 221–2

- ^ Nisbett 2009

- ^ Olness 2003

Bibliography

- Alland, Alexander, Jr (2002). Race in Mind. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 79–80.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "American Anthropological Association Statement on 'Race' and Intelligence". American Anthropological Association. December 1994.

- "American Anthropological Association Statement on 'Race'". American Anthropological Association. 17 May 1998.

- "AAPA Statement on Biological Aspects of Race". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 101: 569–570. 1996.

- Aronson, E; Wilson, TD; Akert, AM (2005). Social Psychology (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-178686-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bartholomew, David J (2004). Measuring Intelligence: Facts and Fallacies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54478-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beals, KL; Smith, CL; Dodd, SM (June 1984). "Brain size, cranial morphology, climate, and time machines". Current Anthropology. 25 (3): 301–30. doi:10.1086/203138.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Behrman, JR; Alderman, H; Hoddinott, J (2004). "Hunger and Malnutrition" (PDF). Copenhagen Consensus.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bellinger, David C; Stiles, Karen M; Needleman, Herbert L (December 1992). "Low-Level Lead Exposure, Intelligence and Academic Achievement: A Long-term Follow-up Study". Pediatrics. 90 (6): 855–61. PMID 1437425.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berlet, Chip (Summer 2003). "Into the Mainstream". Intelligence Report (110). Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Byrd, Desiree A; Touradji, Pegah; Tang, Ming-Xin; Manly, Jennifer J (2004). "Cancellation test performance in African American, Hispanic, and white elderly". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 10 (3): 401–11. doi:10.1017/S1355617704103081.

- Block, Ned (2002). "How heritability misleads about race". In Fish, Jefferson (ed.). Race and Intelligence: Separating Science from Myth. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Borsboom, Denny (September 2006). "The attack of the psychometricians". Psychometricka. 71 (3): 425–40. doi:10.1007/s11336-006-1447-6. PMC 2779444. PMID 19946599.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bower,, B (12 February 2005). "Asian kids' IQ lift: reading system may boost Chinese scores". Science News.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Brace, C Loring (1999). "An Anthropological Perspective on 'Race' and Intelligence: The non-clinal nature of human cognitive capabilities". Journal of Anthropological Research. 55 (2): 245–64. JSTOR 3631210.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brace, C. Loring (2005). Race is a four letter word. Oxford University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-19-517351-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "race". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2012.

- Brown, Robert T; Reynolds, Cecil R; Whitaker, Jean S (1999). "Bias in Mental Testing since "Bias in Mental Testing"". School Psychology Quarterly. 14 (3): 208–38. doi:10.1037/h0089007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bryc, Katarzyna; Autona, Adam; Nelsonb, Matthew R.; Oksenberg, Jorge R.; Hauser, Stephen L.; Williams, Scott; Froment, Alain; Bodof, Jean-Marie; Wambebeg, Charles (2009). "Genome-wide patterns of population structure and admixture in West Africans and African Americans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (2): 786–91. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909559107. PMC 2818934. PMID 20080753.

- Campbell, FA; Ramey, CT (1994). "Effects of early intervention on intellectual and academic achievement: A follow-up study of children from low-income families". Child Development. 65: 684–698.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Frances A; Ramey, Craig T; Pungello, Elizabeth; Sparling, Joseph; Miller-Johnson, Shari (2002). "Early Childhood Education: Young Adult Outcomes From the Abecedarian Project". Applied Developmental Science. 6: 42–57.

- Caspi, A; Williams, B; Kim-Cohen, J; Craig, Ian W; Milne, Barry J; Poulton, Richie; Schalkwyk, Leonard C; Taylor, Alan; Werts, Helen (2007). "Moderation of breastfeeding effects on the IQ by genetic variation in fatty acid metabolism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (47): 18860. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10418860C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704292104. PMC 2141867. PMID 17984066.

- Ceci, SJ; Williams, WM (2009). "Darwin 200: Should scientists study race and IQ? Yes: the scientific truth must be pursued". Nature. 457 (7231): 788. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..788C. doi:10.1038/457788a. PMID 19212385.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cochran, G; Hardy, J; Harpending, H (2006). "Natural History of Ashkenazi Intelligence" (PDF). Journal of Biosocial Science. 38 (5): 659–93.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cooper, Richard (2005). "Race and IQ: Molecular Genetics as Deus ex Machina". American Psychologist. 60 (1): 71–6.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Controversial Nobel winner resigns". CNN. 25 October 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Cronshaw, Steven F; Hamilton, Leah K; Onyura, Betty R; Winston, Andrew S (September 2006). "Case for Non-Biased Intelligence Testing Against Black Africans Has Not Been Made: A Comment on Rushton, Skuy, and Bons". International Journal of Selection and Assessment. 14 (3): 278. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00346.x.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - Deary, Ian J (2001). Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-289321-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Deary, IJ; Johnson, W; Houlihan, LM (2009). "Genetic foundations of human intelligence". Human Genetics. 126 (1): 215–32. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0655-4. PMID 19294424.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Demetriou, Andreas; Kui, Zhang Xiang; Spanoudis, George; Christou, Constantinos; Kyriakides, Leonidas; Platsidou, Maria (March–April 2005). "The architecture, dynamics, and development of mental processing: Greek, Chinese, or Universal?". Intelligence. 33 (2): 109–41. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2004.10.003.

- Dick, DM; Aliev, F; Kramer, J; Wang, JC; Hinrichs, A; Bertelsen, S; Kuperman, S; Schuckit, M; Nurnberger, J, Jr (2007). "Association of CHRM2 with IQ: converging evidence for a gene influencing intelligence". Behavioral Genetics. 37 (2): 265–72. doi:10.1007/s10519-006-9131-2. PMID 17160701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dickens, James R; Flynn (2001). "Heritability estimates versus large environmental effects: The IQ paradox resolved". Psychological Review. 108 (2): 346–69. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.346. PMID 11381833.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dickens, James R; Flynn (2006). "Black Americans Reduce the Racial IQ Gap: Evidence from Standardization Samples" (PDF). Psychological Science. 16 (10): 913–20.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Elhoweris, Hala; Mutua, Kagendo; Alsheikh, Negmeldin; Holloway, Pauline (2005). "Effect of Children's Ethnicity on Teachers' Referral and Recommendation Decisions in Gifted and Talented Programs". Remedial and Special Education. 26. PRO-ED, Inc.

- Eppig, Christopher; Fincher, Corey L; Thornhill, Randy (2010). "Parasite prevalence and the worldwide distribution of cognitive ability". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1701): 3801–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0973. PMC 2992705. PMID 20591860.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eppig, Christopher (2011). "Why Is Average IQ Higher in Some Places?". Scientific American.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eyferth, K (1961). "Leistungern verscheidener Gruppen von Besatzungskindern Hamburg-Wechsler Intelligenztest für Kinder (HAWIK)". Archiv für die gesamte Psychologie (in German). 113: 222–41.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eysenck, Hans J (1987). "Intelligence and Reaction Time: The Contribution of Arthur Jensen". In Modgil, S; Modgil, C (eds.). Arthur Jensen: Consensus and controversy. New York, NY: Falmer.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Falk, Avner (2008). Anti-semitism: a history and psychoanalysis of contemporary hatred. Praeger. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-313-35385-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fischer, Claude S; Hout, Michael; Sánchez Jankowski, Martín; Lucas, Samuel R; Swidler and, Ann; Vos, Kim (1996). Inequality by Design: Cracking the Bell Curve Myth. Princeton University Press. pp. 191–2.

- Fish, Jefferson M (2002). "Folk Heredity". In Fish, Jefferson M (ed.). Race and Intelligence: Separating Myth from Reality. Laurence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 95, 113. ISBN 0-8058-3757-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flynn, James R (1991). "Reaction times show that both Chinese and British children are more intelligent than one another". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 72: 544–6.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flynn, James R (3 September 2008). "Perspectives: Still a question of black vs white?". New Scientist (2672) (magazine issue ed.).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flynn, James R (2009). "Would you wish the research undone?" (PDF). Nature. 458 (7235): 146. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..146F. doi:10.1038/458146a.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flynn, James R (2010). "The spectacles through which I see the race and IQ debate" (PDF). Intelligence (4): 363–6. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2010.05.001.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fryer, Roland G, Jr; Levitt, Steven D (March 2006). "Testing for Racial Differences in the Mental Ability of Young Children" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER Working Paper No. W12066 ed.).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gale, CR; O'Callaghan, FJ; Bredow, M; Martyn, CN; Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team (2006). "The Influence of Head Growth in Fetal Life, Infancy, and Childhood on Intelligence at the Ages of 4 and 8 Years". Pediatrics. 118 (4): 1486–92. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2629. PMID 17015539.

- Goleman, Daniel (10 April 1988). "An Emerging Theory on Blacks' I.Q. Scores". New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Gottfredson, Linda S (1997). "Mainstream Science on Intelligence (editorial)" (PDF). Intelligence. 24: 13–23. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(97)90011-8.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gottfredson, Linda S (2007). "Applying Double Standards to 'Divisive' Ideas: Commentary on Hunt and Carlson". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2 (2): 216–220.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gould, Stephen Jay (1981). The Mismeasure of Man. New York, London: Norton. ISBN 0-393-30056-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graves, Joseph L. (2001). The Emperor's New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium (Kindle ed.). Rutgers University Press. ASIN B000SARS70.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graves, Joseph L (2002a). "The Misuse of Life History Theory: JP Rushton and the Pseudoscience of Racial Hierarchy". In Fish, Jefferson M (ed.). Race and Intelligence: Separating Myth from Reality. Laurence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 57–94. ISBN 0-8058-3757-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graves, Joseph L, Jr (2002b). "What a tangled web he weaves: Race, reproductive strategies and Rushton's life history theory". Anthropological Theory. 2 (2): 131–54. doi:10.1177/1469962002002002627.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gray, Jeremy R; Thompson, Paul M (2004). "Neurobiology of intelligence: science and ethics" (PDF). Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 5 (6): 471–82. doi:10.1038/nrn1405. PMID 15152197.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grossman, James B; Kaufman (2001). "Evolutionary Psychology: Promise and Perils". In Sternberg, Robert J; Kaufman, James C (eds.). The evolution of intelligence. Routledge. ISBN 0-8058-3267-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help) - Herrnstein, Richard J; Murray, Charles (1994). The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-914673-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ho, KC; Roessmann, U; Straumfjord, JV; Monroe, G (1980a). "Analysis of brain weight: I. Adult brain weight in relation to sex, race, and age". Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 104 (12): 635–40. PMID 6893659.

- Ho, KC; Roessmann, U; Straumfjord, JV; Monroe, G (1980b). "Analysis of brain weight: I. Adult brain weight in relation to body height, weight and surface area". Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 104 (12): 640–5. PMID 6893660.

- Horn, John (1989). "Models of intelligence". In Linn, Robert L (ed.). Intelligence: measurement, theory, and public policy : proceedings of a symposium in honor of Lloyd G. Humphreys. University of Illinois Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-252-01535-9.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hothersall, David (2003). "History of Psychology" (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill: 440–1. ISBN 0-07-284965-7.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hunt, Earl (2010). Human Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-70781-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hunt, Earl; Carlson, Jerry (2007). "Considerations relating to the study of group differences in intelligence". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2 (2): 194–213. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00037.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hunt, Earl; Wittmann, Werner (January–February 2008). "National intelligence and national prosperity". Intelligence. 36 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.11.002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Irvine, SH (1983). "Where intelligence tests fail". Nature. 302 (5907): 371. Bibcode:1983Natur.302..371I. doi:10.1038/302371b0.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Irvine, SH; Berry, JW, eds. (1988). "Human Abilities in Cultural Context". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34482-4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ivanovic, DM; Leiva, BP; Pérez, HT; Olivares, MG; Díaz, NS; Urrutia, MS; Almagià, AF; Toro, TD; Miller, PT (2004). "Head size and intelligence, learning, nutritional status and brain development. Head, IQ, learning, nutrition and brain". Neuropsychologia. 42 (8): 1118–31. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.11.022. PMID 15093150.

- Jensen, Arthur R (1969). "How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?". Harvard Educational Review. 39: 1–123.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jensen, Arthur R (1973). Educability and Group Differences. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-06-012194-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jensen, Arthur R; Whang, PA (1993). "Reaction times and intelligence: a comparison of Chinese-American and Anglo-American children". Journal of Biosocial Science. 25 (3): 397–410. PMID 8360233.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jensen, Arthur R (1998). The g factor: The science of mental ability. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96103-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jensen, AR (2006). Clocking the mind: Mental chronometry and individual differences. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044939-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jensen; Johnson, Arthur R (May–June 1994). "Race and sex differences in head size and IQ". Intelligence. 18 (3): 309–33. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(94)90032-9.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaplan, Jonathan Michael (January 2011). "'Race': What Biology Can Tell Us about a Social Construct". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (ELS). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0005857.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Kaszycka, Katarzyna A.; Štrkalj, Goran; Strzałko, Jan (2009). "Current Views of European Anthropologists on Race: Influence of Educational and Ideological Background". American Anthropologist. 111 (1). American Anthropological Association: 43–56. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01076.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kindermann, Thomas A (1993). "Natural peer groups as contexts for individual development: The case of children's motivation in school". Developmental Psychology. 29 (6): 970–7. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.29.6.970.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lee, James J (2010). "Review of intelligence and how to get It: why schools and culture count". Personality and Individual Differences. 48 (2): 247–55. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.09.015.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lieberman, Leonard (February 2001). "How 'Caucasoids' Got Such Big Crania and Why They Shrank: From Morton to Rushton" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 42: 69–95. doi:10.1086/318434. PMID 14992214.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loehlin, John C (2000). "Group Differences in Intelligence". In Sternberg, Robert J (ed.). The Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.