Angevin kings of England: Difference between revisions

→top: reduce repetition / tighten wording; tweak apostrophes |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

|final ruler = [[John, King of England]] |

|final ruler = [[John, King of England]] |

||

|founding year = 1154 |

|founding year = 1154 |

||

|current head = |

|current head = Christopher Lee Gant Angevins|url=http://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/KingsandQueensofEngland/TheAngevins/TheAngevins.aspx|work=The Official Website of The British Monarchy}}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 16:35, 26 July 2014

| Angevins | |

|---|---|

Arms adopted in 1198 | |

| Parent house | House of Anjou |

| Country | England |

| Founded | 1154 |

| Founder | Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou |

| Current head | Christopher Lee Gant Angevins |

| Final ruler | John, King of England |

| Titles | |

| Website | http://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/KingsandQueensofEngland/TheAngevins/TheAngevins.aspx |

</ref>

}}

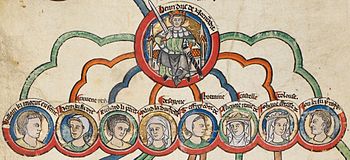

The Angevins /ændʒvɪns/("from Anjou") were a distinct English royal house in the 12th and 13th centuries comprising of three English monarchs—Henry II, Richard I and John. Descended from Ingelger, a ninth-century noble, the Angevin family was of Frankish origin and took its name from the County of Anjou, which Henry inherited on his father's death in 1151. John's son (Henry III) was the first Plantagenet king of England, although some people do not distinguish between the Angevins and the Plantagenets and therefore consider Henry II the first Plantagenet English king.[1][2][3][4][5] The chronicler Gerald of Wales borrowed elements of the Melusine legend to give the Angevins a demonic origin, and jokes existed about the story.[6]

The term Angevin is also sometimes used for the three kings' ancestors from 870 when the family first obtained the title Count of Anjou. Territorial ambitions to expand Angevin holdings brought conflict with neighbouring nobles and expansion of influence into Maine and Touraine. Fulk V, Count of Anjou, failed several times to expand his domain by marrying his daughters to heirs in Normandy and England before arranging the marriage between his son and heir, Geoffrey, to Henry I of England's daughter (and only surviving legitimate child) Matilda. This united the Angevins, the House of Normandy and the House of Wessex into the Plantagenet dynasty. Fulk the Younger, who forged valuable connections during the Second Crusade, surrendered his titles to Geoffrey and became King of Jerusalem with his 1131 marriage to Baldwin II's daughter Melisende.

Geoffrey (Fulk's eldest son) succeeded when his father left for Jerusalem, whilst Baldwin III (his eldest son with Melisende) inherited Jerusalem after Fulk's death in 1143. In 1154 Geoffrey's son, Henry II of England, won control of England and Normandy and expanded the family's holdings into what was later known as the Angevin Empire with his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. Historians consider that members of the family after 1204, when John lost Anjou and the Angevins' continental territory to the House of Capet, are known as Plantagenets (from a nickname for Geoffrey) until the reign of Richard II. The dynasty is then considered to have split into two cadet branches, the House of Lancaster and the House of York.

Origins

The Angevins descended from a ninth-century noble, Ingelger, with the family holding the title Count of Anjou beginning in 870. Although the main line of descent from Ingelger ended in 1060, cognatic kinship continued from Geoffrey II, Count of Gâtinais and Ermengarde of Anjou (daughter of Fulk III of Anjou).[7][8] The Angevins struggled successfully for regional power with neighbouring provinces such as Normandy and Brittany, extending their influence into Maine and Touraine. Although Fulk V, Count of Anjou married his daughter Alice to the heir of Henry I of England, William Adelin, to quash competition from Normandy, the prince drowned in the wreck of the White Ship.[9] Fulk then married his daughter Sibylla to William Clito, heir to Henry's older brother Robert Curthose, but Henry had the marriage annulled because of the rival claim to his throne. Finally, Fulk married his son and heir (Geoffrey) to Henry's daughter—and only surviving legitimate child—Matilda, beginning the Plantagenet dynasty.

Arrival in England

Matilda's father (Henry I of England) named her as heir to his large holdings in what are now France and England,[10] but when Henry died her cousin Stephen had himself proclaimed king.[11] Although Geoffrey had little interest in England, he supported Matilda by entering Normandy to claim her inheritance.[12] Matilda landed in England to challenge Stephen, and was declared "Lady of the English"; this resulted in the civil war known as the Anarchy. When Matilda was forced to release Stephen in a hostage exchange for her half-brother Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, Stephen was re-crowned. Matilda was never crowned, since the English conflict was inconclusive, but Geoffrey secured the Duchy of Normandy. Matilda's son, Henry II, became wealthy after acquiring the Duchy of Aquitaine by his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. After skillful negotiation with King Stephen and the war-weary English barons, Henry agreed to the Treaty of Wallingford and was recognised as Stephen's heir.[13]

When Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury died, Henry II appointed his friend Thomas Becket to the post to re-establish what Henry saw as his rights over the church in England and to reassert privileges held by his father-in-law. Henry had clashed with the church over whether bishops could excommunicate royal officials without his permission, and whether he could try clerics without their appealing to Rome. Becket opposed Henry's Constitutions of Clarendon, fleeing into exile. Relations later improved, allowing Becket's return, but soured again when Becket saw the coronation of Henry's son as coregent by the Archbishop of York as a challenge to his authority and excommunicated those who had offended him. When he heard the news, Henry said: "What miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk". Three of Henry's men murdered Becket in Canterbury Cathedral (probably by misadventure) after Becket resisted a botched arrest attempt.[14] In Christian Europe Henry was considered complicit in this crime (making him a pariah), and he was forced to walk barefoot into the cathedral and be scourged by monks as a penance.[11]

In 1155, Pope Adrian IV gave Henry a papal blessing to expand his power into Ireland to reform the Irish church.[15] This was not an urgent matter until Henry allowed Dermot of Leinster to recruit soldiers in England and Wales, including Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (known as Strongbow), for use in Ireland. The knights assumed the role of colonisers, accruing autonomous power (which concerned Henry). When Dermot died in 1171 his son-in-law Strongbow seized considerable territory, but to defuse the controversy surrounding Becket's murder Henry re-established all fiefs in Ireland.[16]

When Henry II tried to give his landless youngest son John a wedding gift of three castles, his wife and three eldest sons rebelled in the Revolt of 1173–1174. Louis VII encouraged the elder sons to destabilise his mightiest subject, hastening their inheritances. William the Lion and disgruntled subjects of Henry II also joined the revolt for their own reasons, and it took 18 months for Henry to force the rebels to submit to his authority.[17] In Le Mans in 1182, Henry II gathered his children to plan a partible inheritance in which his eldest son (also called Henry) would inherit England, Normandy and Anjou; Richard the Duchy of Aquitaine; Geoffrey Brittany, and John Ireland. This degenerated into further conflict, and the younger Henry again rebelled before he died of dysentery. Geoffrey died after an 1186 tournament accident; Henry was reluctant to have a sole heir,[18] and in 1189 Richard and Philip II of France took advantage of his failing health. Henry was forced to accept humiliating peace terms, including naming Richard as his sole heir. When he died shortly afterwards, his last words to Richard were said to be: "God grant that I may not die until I have my revenge on you".[19]

Decline

On the day of Richard's English coronation there was a mass slaughter of Jews, described by Richard of Devizes as a "holocaust".[20] After his coronation, Richard put the Angevin Empire's affairs in order before joining the Third Crusade to the Middle East in early 1190. Opinions of Richard by his contemporaries varied. He had rejected and humiliated the king of France's sister; deposed the king of Cyprus and sold the island; insulted and refused to give spoils from the Third Crusade to Leopold V, Duke of Austria, and allegedly arranged the assassination of Conrad of Montferrat. His cruelty was exemplified by the massacre of 2,600 prisoners in Acre.[21] However, Richard was respected for his military leadership and courtly manners. Despite victories in the Third Crusade he failed to capture Jerusalem, retreating from the Holy Land with a small band of followers.[22]

Richard was captured by Leopold on his return journey. He was transferred to Henry the Lion, and a 25-percent tax on goods and income was required to pay his 150,000-mark ransom.[23][24] Philip II of France had overrun Normandy, while John of England controlled much of Richard's remaining lands.[25] However, when Richard returned to England he forgave John and re-established his control.[26] Leaving England permanently in 1194, Richard fought Phillip for five years for the return of holdings seized during his incarceration.[27] On the brink of victory, he was wounded by an arrow during the siege of Château de Châlus-Chabrol and died ten days later.[28]

His failure to produce an heir caused a succession crisis. Anjou, Brittany, Maine and Touraine chose Richard's nephew Arthur as heir, while John succeeded in England and Normandy. Philip II of France again destabilised the Plantagenet territories on the European mainland, supporting his vassal Arthur's claim to the English crown. Eleanor supported her son John, who was victorious at the Battle of Mirebeau and captured the rebel leadership.[29]

Arthur was murdered (allegedly by John), and his sister Eleanor would spend the rest of her life in captivity. John's behaviour drove a number of French barons to side with Phillip, and the resulting rebellions by Norman and Angevin barons ended John's control of his continental possessions—the de facto end of the Angevin Empire, although Henry III would maintain his claim until 1259.[30]

After re-establishing his authority in England, John planned to retake Normandy and Anjou by drawing the French from Paris while another army (under Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor) attacked from the north. However, his allies were defeated at the Battle of Bouvines in one of the most decisive battles in French history.[31][32] John's nephew Otto retreated and was soon overthrown, with John agreeing to a five-year truce. Philip's victory was crucial to the political order in England and France, and the battle was instrumental in establishing absolute monarchy in France.[33]

John's French defeats weakened his position in England. The rebellion of his English vassals resulted in the Magna Carta, which limited royal power and established common law. This would form the basis of every constitutional battle of the 13th and 14th centuries.[34] The barons and the crown failed to abide by the Magna Carta, leading to the First Barons' War when rebel barons provoked an invasion by Prince Louis. John's death and William Marshall's appointment as protector of nine-year-old Henry III are considered the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty by some historians.[35] Marshall won the war with victories at Lincoln and Dover in 1217, leading to the Treaty of Lambeth in which Louis renounced his claims.[36] In victory, the Marshal Protectorate reissued the Magna Carta as the basis of future government.[37] The word "Angevin" has also become associated with later Houses of Anjou awarded the title of "count" by French kings.

Legacy

House of Plantagenet

Prince Louis's invasion is considered by some historians to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty. The outcome of the military situation was uncertain at John's death; William Marshall saved the dynasty, forcing Louis to renounce his claim with a military victory.[36] However, Philip had captured all the Angevin possessions in France except Gascony. This collapse had several causes, including long-term changes in economic power, growing cultural differences between England and Normandy and (in particular) the fragile, familial nature of Henry's empire.[38] Henry III continued his attempts to reclaim Normandy and Anjou until 1259, but John's continental losses and the consequent growth of Capetian power during the 13th century marked a "turning point in European history".[39]

Richard of York adopted "Plantagenet" as a family name for himself and his descendants during the 15th century. Plantegenest (or Plante Genest) was Geoffrey's nickname, and his emblem may have been the common broom (planta genista in medieval Latin).[40] It is uncertain why Richard chose the name, but it emphasised Richard's hierarchal status as Geoffrey's (and six English kings') patrilineal descendant during the Wars of the Roses. The retrospective use of the name for Geoffrey's male descendants was popular during the Tudor period, perhaps encouraged by the added legitimacy it gave Richard's great-grandson Henry VIII of England.[41]

Descent

Through John, descent from the Angevins (legitimate and illegitimate) is widespread and includes all subsequent monarchs of England and the United Kingdom. He had five legitimate children with Isabella:

- Henry III – king of England for most of the 13th century

- Richard – a noted European leader and King of the Romans in the Holy Roman Empire[42]

- Joan – married Alexander II of Scotland, becoming his queen consort.[43]

- Isabella – married the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II.[44]

- Eleanor – married William Marshal's son (also called William) and, later, English rebel Simon de Montfort.[45]

John also had illegitimate children with a number of mistresses, including nine sons—Richard, Oliver, John, Geoffrey, Henry, Osbert Gifford, Eudes, Bartholomew and (probably) Philip—and three daughters—Joan, Maud and (probably) Isabel.[46] Of these Joan was the best known, since she married Prince Llywelyn the Great of Wales.[47]

Contemporary opinion

Henry was an unpopular king, and few grieved his death;[48] William of Newburgh wrote during the 1190s, "In his own time he was hated by almost everyone". He was widely criticised by contemporaries, even in his own court.[49][50] Henry's son Richard's contemporary image was more nuanced, since he was the first king who was also a knight.[51] Known as a valiant, competent and generous military leader, he was criticised by chroniclers for taxing the clergy for the Crusade and his ransom; clergy were usually exempt from taxes.[52]

Chroniclers Richard of Devizes, William of Newburgh, Roger of Hoveden and Ralph de Diceto were generally unsympathetic to John's behaviour under Richard, but more tolerant of the earliest years of John's reign.[53] Accounts of the middle and later years of his reign are limited to Gervase of Canterbury and Ralph of Coggeshall, neither of whom were satisfied with John's performance as king.[54][55] His later negative reputation was established by two chroniclers writing after the king's death: Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris (the latter claiming that John attempted to convert to Islam, considered untrue by modern historians).[56]

Constitutional impact

Many of the changes Henry introduced during his rule had long-term consequences. His legal innovations are generally considered the basis for English law, with the Exchequer of Pleas a forerunner of the Common Bench at Westminster.[57] Henry's itinerant justices also influenced his contemporaries' legal reforms: Philip Augustus' creation of itinerant bailli, for example, drew on Henry's model.[58] Henry's intervention in Brittany, Wales and Scotland had a significant long-term impact on the development of their societies and governments.[59] John's reign, despite its flaws, and his signing of the Magna Carta were seen by Whig historians as positive steps in the constitutional development of England and part of a progressive and universalist course of political and economic development in medieval England.[60] Winston Churchill said, "[W]hen the long tally is added, it will be seen that the British nation and the English-speaking world owe far more to the vices of John than to the labours of virtuous sovereigns".[61] The Magna Carta was reissued by the Marshal Protectorate and later as a foundation of future government.[37]

Historiography

According to historian John Gillingham, Henry and his reign have attracted historians for many years and Richard (whose reputation has "fluctuated wildly")[62] is remembered largely because of his military exploits. Steven Runciman, in the third volume of the History of the Crusades, wrote: "He was a bad son, a bad husband, and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier."

Eighteenth-century historian David Hume wrote that the Angevins were pivotal in creating a genuinely English monarchy and, ultimately, a unified Britain.[63] Interpretations of the Magna Carta and the role of the rebel barons in 1215 have been revised; although the charter's symbolic, constitutional value for later generations is unquestionable, during John's reign most historians consider it a failed peace agreement between factions.[64] John's opposition to the papacy and his promotion of royal rights and prerogatives won favour from 16th-century Tudors. John Foxe, William Tyndale and Robert Barnes viewed John as an early Protestant hero, and Foxe included the king in his Book of Martyrs.[65] John Speed's 1632 Historie of Great Britaine praised John's "great renown" as king, blaming biased medieval chroniclers for the king's poor reputation.[66] Similarly, later Protestant historians considered Henry's role in Thomas Becket's death and his disputes with the French praiseworthy.[67] Similarly,

Increased access to contemporary records during the late Victorian era led to a recognition of Henry's contributions to the evolution of English law and the exchequer.[68] William Stubbs called Henry a "legislator king" because of his responsibility for major, long-term reforms in England; in contrast, Richard was "a bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler, and a vicious man".[68][69]

He was a bad king: his great exploits, his military skill, his splendour and extravagance, his poetical tastes, his adventurous spirit, do not serve to cloak his entire want of sympathy, or even consideration, for his people. He was no Englishman, but it does not follow that he gave to Normandy, Anjou, or Aquitaine the love or care that he denied to his kingdom. His ambition was that of a mere warrior: he would fight for anything whatever, but he would sell everything that was worth fighting for. The glory that he sought was that of victory rather than conquest.

William Stubbs, on Richard[70]

The growth of the British Empire led historian Kate Norgate to begin detailed research into Henry's continental possessions and create the term "Angevin Empire" during the 1880s.[71][72] However, 20th-century historians challenged many of these conclusions. During the 1950s, Jacques Boussard, John Jolliffe and others focused on the nature of Henry's "empire"; French scholars, in particular, analysed the mechanics of royal power during this period.[73] Anglocentric aspects of many histories of Henry's reign were challenged beginning in the 1980s, with efforts to unite British and French historical analyses of the period.[74] Detailed study of Henry's written records has cast doubt on earlier interpretations; Robert Eyton's 1878 volume (tracing Henry's itinerary by deductions from pipe rolls), for example, has been criticised for not acknowledging uncertainty.[75] Although many of Henry's royal charters have been identified, their interpretation, the financial information in the pipe rolls and broad economic data from his reign has proven more challenging than once thought.[76][77] Significant gaps in the historical analysis of Henry remain, particularly about his rule in Anjou and the south of France.[78]

Interest in the morality of historical figures and scholars waxed during the Victorian period, leading to increased criticism of Henry's behaviour and Becket’s death.[79] Historians relied on the judgement of chroniclers to focus on John's ethos. Norgate wrote that John's downfall was due not to his military failures but his "almost superhuman wickedness", and James Ramsay blamed John's family background and innate cruelty for his downfall.[80][81]

Richard's sexuality has been controversial since the 1940s, when John Harvey challenged what he saw as "the conspiracy of silence" surrounding the king's homosexuality with chronicles of Richard's behaviour, two public confessions, penances and childless marriage.[82] Opinion remains divided, with Gillingham arguing against Richard's homosexuality[82] and Jean Flori acknowledging its possibility.[82][83]

According to recent biographers Ralph Turner and Lewis Warren, although John was an unsuccessful monarch his failings were exaggerated by 12th- and 13th-century chroniclers.[84] Jim Bradbury echoes the contemporary consensus that John was a "hard-working administrator, an able man, an able general" with, as Turner suggests, "distasteful, even dangerous personality traits".[85] John Gillingham (author of a biography of Richard I) concurs, considering John a less-effective general than Turner and Warren do. Bradbury takes a middle view, suggesting that modern historians have been overly lenient in evaluating John's flaws.[86] Popular historian Frank McLynn wrote that the king's modern reputation amongst historians is "bizarre" and, as a monarch, John "fails almost all those [tests] that can be legitimately set".[87]

In popular culture

Henry II appears as a fictionalised character in several modern plays and films. The king is a central character in James Goldman's 1966 play The Lion in Winter, set in 1183 and narrating an imaginary encounter between Henry's family and Philip Augustus over Christmas at Chinon. Philip's strong character contrasts with John, an "effete weakling".[88] In the 1968 film, Henry is a sacrilegious, fiery and determined king.[89][90] Henry also appears in Jean Anouilh's play, Becket, which was (filmed in 1964).[91] The Becket conflict is the basis for T. S. Eliot's play, Murder in the Cathedral, an exploration of Becket's death and Eliot's religious interpretation of it.[92]

During the Tudor period, popular representations of John emerged.[93] He appeared as a "proto-Protestant martyr" in the anonymous play The Troublesome Reign of King John and John Bale's morality play Kynge Johan, in which John attempts to save England from the "evil agents of the Roman Church".[94] Shakespeare's anti-Catholic King John draws on The Troublesome Reign, offering a "balanced, dual view of a complex monarch as both a proto-Protestant victim of Rome's machinations and as a weak, selfishly motivated ruler".[95][96] Anthony Munday's plays The Downfall and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington demonstrate many of John's negative traits, but approve of the king's stand against the Roman Catholic Church.[97] By the mid-17th century, plays such as Robert Davenport's King John and Matilda (based largely on the Elizabethan works) transferred the role of Protestant champion to the barons and focused on John's tyranny.[98] Graham Tulloch noted that unfavourable 19th-century fictionalised depictions of John were influenced by Sir Walter Scott's historical romance, Ivanhoe. They, in turn, influenced the late-19th-century children's author Howard Pyle's The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (which cast John as the principal villain of the Robin Hood narrative). During the 20th century, John also appeared in fictional books and films with Robin Hood. Sam De Grasse's John, in the 1922 film version, commits atrocities and acts of torture.[99] Claude Rains' John, in the 1938 version with Errol Flynn, began a cinematic trend in which John was an "effeminate ... arrogant and cowardly stay-at-home".[76][100] John's character highlights King Richard's virtues and contrasts with the Sheriff of Nottingham, the "swashbuckling villain" opposing Robin. In the Disney cartoon version, John (voiced by Peter Ustinov) is a "cowardly, thumbsucking lion".[101]

In medieval folklore

During the 13th century, a folktale developed in which Richard’s minstrel Blondel roamed (singing a song known only to him and Richard) to find Richard's prison.[102] This story was the foundation of André Ernest Modeste Grétry's opera Richard Coeur-de-Lion, and inspired the opening of Richard Thorpe's film version of Ivanhoe. Sixteenth-century tales of Robin Hood began describing him as a contemporary (and supporter) of Richard the Lionheart; Robin became an outlaw during the reign of Richard's evil brother, John, while Richard was fighting in the Third Crusade.[103]

See also

- Further information on the Angevin domains – Angevin Empire

- Details on the successors of the Angevins and the wider family – House of Plantagenet

- Other dynasties called "Angevin" by some historians – Capetian House of Anjou and Valois House of Anjou

References

- ^ Blockmans & Hoppenbrouwers 2014, p. 173

- ^ Aurell 2003

- ^ Gillingham 2007, pp. 15–23 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Power 2007, pp. 85–86

- ^ Warren 1991, pp. 228–229

- ^ Warren 1978, p. 2

- ^ Davies 1997, p. 190

- ^ Vauchez 2000, p. 65

- ^ Davies 1999, p. 309

- ^ Hooper 1996, p. 50

- ^ a b Schama 2000, p. 117

- ^ Grant 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Ashley 2003, p. 73.

- ^ Schama 2000, p. 142

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 79–80

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 82–92

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 86

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 109

- ^ Ackroyd 2000, p. 54

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 128

- ^ Carlton 2003, p. 42

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 133

- ^ Davies 1999, p. 351

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 139

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 140–141

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 145

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 146

- ^ Turner 1994, pp. 100

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 161–169

- ^ Favier 1993, p. 176

- ^ Contramine 1992, p. 83

- ^ Smedley 1836, p. 72

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 217

- ^ "The official website of The British Monarchy". The Angevins. The Royal Household © Crown Copyright.

- ^ a b Jones 2012, pp. 221–222 Cite error: The named reference "Jones221" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Danziger & Gillingham 2003, p. 271 Cite error: The named reference "DanzigerGillingham" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Gillingham 1994, p. 31

- ^ Carpenter 1996, p. 270

- ^ Plant 2007

- ^ Wagner 2001, p. 206

- ^ Carpenter 1996, p. 223

- ^ Carpenter 1996, p. 277

- ^ Carpenter 2004, p. 344

- ^ Carpenter 2004, p. 306

- ^ Richardson 2004, p. 9

- ^ Carpenter 2004, p. 328

- ^ Strickland 2007, p. 187

- ^ White 2000, p. 213

- ^ Vincent 2007b, p. 330

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 484–485

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 322

- ^ Gillingham 2007, p. 2 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Warren 2000, p. 7

- ^ Gillingham 2007, p. 15 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Warren 2000, pp. 11, 14

- ^ Brand 2007, p. 216

- ^ HallamEverard 2001, p. 211

- ^ Davies 1990, pp. 22–23

- ^ Dyer 2009, p. 4

- ^ Churchill 1958, p. 190

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 484

- ^ Gillingham 2007, p. 2 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Huscroft 2005, p. 174

- ^ Bevington 2002, p. 432

- ^ Gillingham 2007, p. 4 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Gillingham 2007, p. 3 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ a b Gillingham 2007, p. 10 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ White 2000, p. 3

- ^ Stubbs 1874, pp. 550–551

- ^ Gillingham 2007, p. 16 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Aurell 2003, p. 15

- ^ Aurell 2003, p. 19

- ^ Gillingham 2007, p. 21 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Gillingham 2007, pp. 279–281 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ a b Gillingham 2007, pp. 286, 299 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Barratt 2007, pp. 248–294

- ^ Gillingham 2007, pp. 22 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Gillingham 2007, pp. 5–7 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGillingham2007 (help)

- ^ Norgate 1902, p. 286

- ^ Ramsay 1903, p. 502

- ^ a b c Gillingham 1994, pp. 119–139

- ^ Flori 1999, p. 448

- ^ Bradbury 2007, pp. 353

- ^ Turner 1994, pp. 23

- ^ Bradbury 2007, p. 361

- ^ McLynn 2007, pp. 472–473

- ^ Elliott 2011, pp. 109–110

- ^ Martinson 2007, p. 263

- ^ Palmer 2007, p. 46

- ^ Anouilh 2005, p. xxiv

- ^ Tiwawi & Tiwawi 2007, p. 90

- ^ Bevington 2002, pp. 432

- ^ Curren-Aquino 1989, pp. 19

- ^ Curren-Aquino 1989, p. 19

- ^ Bevington 2002, pp. 454

- ^ Potter 1998, p. 70

- ^ Maley 2010, p. 50

- ^ Aberth 2003, p. 166

- ^ Potter 1998, pp. 210

- ^ Potter 1998, p. 218

- ^ Flori 1999, pp. 191–192

- ^ Holt 1982, p. 170

Bibliography

- Aberth, John (2003). A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93886-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ackroyd, Peter (2000). London – A Biography. Vintage. ISBN 0-09-942258-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Anouilh, Jean (2005). Antigone. Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-69540-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ashley, Mike (2003). A Brief History of British Kings and Queens. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1104-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Aurell, Martin (2003). L'Empire de Plantagenêt, 1154–1224. Tempus. ISBN 978-2-262-02282-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)Template:Fr icon - Barratt, Nick (2007). "Finance and the Economy in the Reign of Henry II". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas (eds.). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bevington, David (2002). "Literature and the theatre". In Loewenstein, David; Mueller, Janel (eds.). The Cambridge History of Early Modern English Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521631563.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blockmans, Wim; Hoppenbrouwers, Mark (2014). Introduction to Medieval Europe, 300–1500 (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781317934257.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bradbury, Jim (2007). "Philip Augustus and King John: Personality and History". In Church, S.D. (ed.). King John: New Interpretations. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9780851157368.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brand, Paul (2007). "Henry II and the Creation of the English Common Law". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas (eds.). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carlton, Charles (2003). Royal Warriors: A Military History of the British Monarchy. Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-47265-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carpenter, David (1996). Royal Warriors: A Military History of the British Monarchy. Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-137-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carpenter, David (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Churchill, Winston (1958). A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume 1. Cassell. ISBN 978-0304363896.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Contramine, Phillipe (1992). Histoire militaire de la France (tome 1, des origines à 1715) (in French). PUF. ISBN 2-13-048957-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curren-Aquino, Deborah T (1989). "Introduction: King John Resurgent". In Curren-Aquino, Deborah T (ed.). King John: New Interpretations. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 9780874133370.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Danziger, Danny; Gillingham, John (2003). 1215: The Year of Magna Carta. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-82475-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, R. R. (1990). Domination and Conquest: The Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, 1100–1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02977-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Norman (1997). Europe – A History. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6633-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Norman (1999). The Isles – A History. MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-76370-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dyer, Christopher (2009). Making a Living in the Middle Ages: The People of Britain, 850 – 1520. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10191-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Elliott, Andrew B. R. (2011). Remaking the Middle Ages: The Methods of Cinema and History in Portraying the Medieval World. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4624-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Favier, Jean (1993). Dictionnaire de la France médiévale (in French). Fayard.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flori, Jean (1999). Richard Coeur de Lion: le roi-chevalier (in French). Biographie Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-89272-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillingham, John (2007). "Doing Homage to the King of France". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas (eds.). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillingham, John (2007). "Historians without Hindsight: Coggshall, Diceto and Howden on the Early Years of John's Reign". In Church, S.D. (ed.). King John: New Interpretations. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9780851157368.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillingham, John (1994). Richard Coeur de Lion: Kingship, Chivalry, and War in the Twelfth Century. Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-084-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grant, Lindy (2005). Architecture and Society in Normandy, 1120–1270. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10686-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hallam, Elizabeth M.; Everard, Judith A. (2001). Capetian France, 987–1328 (2nd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40428-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holt, J. C. (1982). Robin Hood. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hooper, Nicholas (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44049-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England, 1042–1217. Pearson. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Dan (2012). The Plantagenets: The Kings Who Made England. HarperPress. ISBN 0-00-745749-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maley, Willy (2010). "'And bloody England into England gone': Empire, Monarchy, and Nation in King John". In Maley, Willy; Tudeau, Margaret (eds.). This England, That Shakespeare. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754666028.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martinson, Amanda A. (2007). The Monastic Patronage of King Henry II in England, 1154–1189 (Ph.D. thesis). University of St Andrews.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McLynn, Frank (2007). John Lackland. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-7126-9417-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Norgate, Kate (1902). John Lackland. Macmillan. ISBN 9781230315256.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Palmer, R. Barton (2007). "Queering the Lion Heart: Richard I in The Lion in Winter on Stage and Screen". In Kelly, Kathleen Coyne; Pugh, Tison (eds.). Queer Movie Medievalisms. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-7592-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Plant, John S (2007). "The Tardy Adoption of the Plantagenet Surname". Nomina. 30: 57–84. ISSN 0141-6340.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Potter, Lois (1998). Playing Robin Hood: the Legend as Performance in Five Centuries. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-663-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Power, Daniel (2007). "Henry, Duke of the Normans (1149/50-1189)". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas (eds.). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ramsay, James Henry (1903). 'The Angevin Empire. Sonnenschein. ISBN 9781143823558.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richardson, Douglas (2004). Plantagenet Ancestry: a Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Genealogical Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8063-1750-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schama, Simon (2000). A History of Britain – At the edge of the world. BBC. ISBN 0-563-53483-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smedley, Edward (1836). The History of France, from the final partition of the Empire of Charlemagne to the Peace of Cambray. Baldwin and Craddock. p. 72.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Strickland, Matthew (2007). "On the Instruction of a Prince: The Upbringing of Henry, the Young King". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas (eds.). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stubbs, William (1874). The Constitutional History of England, in its Origin and Development. Clarendon Press. OCLC 2653225.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tiwawi, Subha; Tiwawi, Maneesha (2007). The Plays of T.S. Eliot. Atlantic. ISBN 978-81-269-0649-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Turner, Ralph V (1994). King John (The Medieval World). Longman Medieval World Series. ISBN 978-0-582-06726-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vauchez, Andre (2000). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Routledge. ISBN 1-57958-282-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vincent, Nicholas (2007b). "The Court of Henry II". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas (eds.). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wagner, John (2001). Encyclopedia of the Wars of the Roses. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-358-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Warren, W. L. (1991). King John. Methuen. ISBN 0-413-45520-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Warren, W. L. (2000). Henry II (Yale ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08474-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Warren, Wilfred Lewis (1978). King John, Revised Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03643-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, Graeme J. (2000). Restoration and Reform, 1153–1165: Recovery From Civil War in England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55459-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)