2016 New York and New Jersey bombings: Difference between revisions

Parsley Man (talk | contribs) |

Three different citations pointing to the same article have been merged into one (See Talk page) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

The [[Federal Bureau of Investigation]] (FBI), the [[Joint Terrorism Task Force]] (JTTF), [[United States Department of Homeland Security|Homeland Security]], and the [[Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives]] (ATF) responded to the scene of the Chelsea bombing and were involved in the investigation, in addition to the [[New York City Fire Department]] (FDNY) and the NYPD. Initially, the Seaside Park and Manhattan bombings were investigated as separate incidents, but over a period of two days, the investigation yielded similarities between the two incidents, leading the investigators to determine that they were connected, and therefore that it was to be investigated as one overall composite terrorist act or endeavor, committed by the same party.<ref name="NYT" /><ref name=NBC.Intentional>{{cite web|url=http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/29-hurt-manhattan-explosion-called-intentional-act-n650041|title='An Act of Terrorism': Investigators Hunting for Clues in NYC Bomb That Injured 29|work=NBC News|date=September 18, 2016|accessdate=September 18, 2016|first1=Jonathan|last1=Dienst|first2=Tom|last2=Winter|first3=Richard|last3=Esposito|first4=Emmanuelle|last4=Saliba|first5=Phil|last5=Helsel|first6=Elisha|last6=Fieldstadt}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/live/2016/sep/18/manhattan-explosion-several-injured-in-blast-rolling-report|title=New York explosion: Cuomo says 'no evidence of international terrorism' – as it happened|first1=Elle|last1=Hunt|first2=Alan|last2=Yuhas|date=September 18, 2016|accessdate=September 18, 2016|publisher=The Guardian}}</ref> |

The [[Federal Bureau of Investigation]] (FBI), the [[Joint Terrorism Task Force]] (JTTF), [[United States Department of Homeland Security|Homeland Security]], and the [[Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives]] (ATF) responded to the scene of the Chelsea bombing and were involved in the investigation, in addition to the [[New York City Fire Department]] (FDNY) and the NYPD. Initially, the Seaside Park and Manhattan bombings were investigated as separate incidents, but over a period of two days, the investigation yielded similarities between the two incidents, leading the investigators to determine that they were connected, and therefore that it was to be investigated as one overall composite terrorist act or endeavor, committed by the same party.<ref name="NYT" /><ref name=NBC.Intentional>{{cite web|url=http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/29-hurt-manhattan-explosion-called-intentional-act-n650041|title='An Act of Terrorism': Investigators Hunting for Clues in NYC Bomb That Injured 29|work=NBC News|date=September 18, 2016|accessdate=September 18, 2016|first1=Jonathan|last1=Dienst|first2=Tom|last2=Winter|first3=Richard|last3=Esposito|first4=Emmanuelle|last4=Saliba|first5=Phil|last5=Helsel|first6=Elisha|last6=Fieldstadt}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/live/2016/sep/18/manhattan-explosion-several-injured-in-blast-rolling-report|title=New York explosion: Cuomo says 'no evidence of international terrorism' – as it happened|first1=Elle|last1=Hunt|first2=Alan|last2=Yuhas|date=September 18, 2016|accessdate=September 18, 2016|publisher=The Guardian}}</ref> |

||

Within hours after the attack, officials [[:File:Loud-explosion-reported-manhattan-chelsea-neighborhood.webm|determined]] that the explosion was intentional, and ruled out the possibility of a [[Gas explosion|natural gas explosion]].<ref name="NYT"/><ref name="usa today">{{cite web|first1=Melanie|last1=Eversley|first2=Kevin|last2=McCoy|title=Big blast, 29 injuries in NYC; pressure cooker device removed nearby|url=http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/09/17/explosion-new-york-chelsea-neighborhood/90605526/|newspaper=USA Today|date=September 17, 2016|accessdate=September 17, 2016}}</ref> Investigators did not immediately find evidence of a [[terrorism]] link,<ref name="NYT"/><ref name="CNN"/> initially leaving open the possibility of [[arson]] or [[vandalism]] at the time.<ref>{{cite news|last1=David|first1=Javier E.|title=NYC Mayor DeBlasio: Chelsea explosion 'intentional', but no immediate terror link|url=http://www.cnbc.com/2016/09/17/explosion-injuries-reported-in-nycs-chelsea-section.html|work=CNBC|date=September 17, 2016|accessdate=September 17, 2016}}</ref> A link to terrorism was discovered in the following days.<ref name="HuntforRahami" /><ref name=" |

Within hours after the attack, officials [[:File:Loud-explosion-reported-manhattan-chelsea-neighborhood.webm|determined]] that the explosion was intentional, and ruled out the possibility of a [[Gas explosion|natural gas explosion]].<ref name="NYT"/><ref name="usa today">{{cite web|first1=Melanie|last1=Eversley|first2=Kevin|last2=McCoy|title=Big blast, 29 injuries in NYC; pressure cooker device removed nearby|url=http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/09/17/explosion-new-york-chelsea-neighborhood/90605526/|newspaper=USA Today|date=September 17, 2016|accessdate=September 17, 2016}}</ref> Investigators did not immediately find evidence of a [[terrorism]] link,<ref name="NYT"/><ref name="CNN"/> initially leaving open the possibility of [[arson]] or [[vandalism]] at the time.<ref>{{cite news|last1=David|first1=Javier E.|title=NYC Mayor DeBlasio: Chelsea explosion 'intentional', but no immediate terror link|url=http://www.cnbc.com/2016/09/17/explosion-injuries-reported-in-nycs-chelsea-section.html|work=CNBC|date=September 17, 2016|accessdate=September 17, 2016}}</ref> A link to terrorism was discovered in the following days.<ref name="HuntforRahami" /><ref name="FBI"/> |

||

Both of the Manhattan bombs—the one that exploded and the second that was disabled—were of the same design, using pressure cookers filled with bearings or metal BBs that were rigged with [[Flip (form)|flip]] [[mobile phone|phone]]s and [[Christmas lights]] that set off a small charge of [[hexamethylene triperoxide diamine]] (HMTD), which served as a [[detonator]] for a larger charge of a [[secondary explosive]] similar to [[Tannerite]].<ref name="HuntforRahami" /><ref>{{cite news|last1=Greenemeier|first1=Larry|title=Chemicals Could Be a Key in Investigating the New York and New Jersey Bombings|url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/chemicals-could-be-a-key-in-investigating-the-new-york-and-new-jersey-bombings/|accessdate=September 28, 2016|publisher=Scientific American|date=September 19, 2016}}</ref> |

Both of the Manhattan bombs—the one that exploded and the second that was disabled—were of the same design, using pressure cookers filled with bearings or metal BBs that were rigged with [[Flip (form)|flip]] [[mobile phone|phone]]s and [[Christmas lights]] that set off a small charge of [[hexamethylene triperoxide diamine]] (HMTD), which served as a [[detonator]] for a larger charge of a [[secondary explosive]] similar to [[Tannerite]].<ref name="HuntforRahami" /><ref>{{cite news|last1=Greenemeier|first1=Larry|title=Chemicals Could Be a Key in Investigating the New York and New Jersey Bombings|url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/chemicals-could-be-a-key-in-investigating-the-new-york-and-new-jersey-bombings/|accessdate=September 28, 2016|publisher=Scientific American|date=September 19, 2016}}</ref> |

||

The FBI examined fingerprints from the undetonated West 27th Street pressure cooker bomb and its attached mobile phone.<ref name="CapturedCNN" /> [[DNA evidence]] was also recovered.<ref name=" |

The FBI examined fingerprints from the undetonated West 27th Street pressure cooker bomb and its attached mobile phone.<ref name="CapturedCNN" /> [[DNA evidence]] was also recovered.<ref name="FBI"/> On September 19, the FBI traced the prints, as well as some pictures on the mobile phone, to Ahmad Khan Rahami (see [[#Suspect|below]]).<ref name="Weiss Rizzi Kapp Gardiner 2016" /><ref name="HuntforRahami" /> |

||

Though the explosives in all four incidents were of three different designs, the [[United States Department of Homeland Security|Department of Homeland Security]] found that the bomb-maker followed guidelines featured in ''[[Inspire (magazine)|Inspire]]'', an online magazine published by [[al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/ahmad-rahami-al-qaeda-magazine-bomb-making-article-1.2805807|title=Ahmad Rahami may have followed bomb-making tips from Al Qaeda magazine, memo shows|work=The New York Daily News|date=September 25, 2016|accessdate=September 28, 2016|first=Jason|last=Silverstein}}</ref> |

Though the explosives in all four incidents were of three different designs, the [[United States Department of Homeland Security|Department of Homeland Security]] found that the bomb-maker followed guidelines featured in ''[[Inspire (magazine)|Inspire]]'', an online magazine published by [[al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/ahmad-rahami-al-qaeda-magazine-bomb-making-article-1.2805807|title=Ahmad Rahami may have followed bomb-making tips from Al Qaeda magazine, memo shows|work=The New York Daily News|date=September 25, 2016|accessdate=September 28, 2016|first=Jason|last=Silverstein}}</ref> |

||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

[[File:Video report by Zlatica Hoke, 2016 New York Bombing.webm|thumb|right|thumbtime=1|[[Voice of America]] video report]] |

[[File:Video report by Zlatica Hoke, 2016 New York Bombing.webm|thumb|right|thumbtime=1|[[Voice of America]] video report]] |

||

A note found on the pressure cooker bomb left on West 27th Street referred to [[Anwar al-Awlaki]] (the Muslim cleric who became a senior member of [[al-Qaeda]] and was then killed by a U.S. drone strike), the Boston Marathon bombings, and the [[2009 Fort Hood shooting]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://kwqc.com/2016/09/20/note-on-pressure-cooker-found-in-manhattan-mentioned-boston-bombing-sources-say/|title=Note on Pressure Cooker Found in Manhattan Mentioned Boston Bombing, Sources Say|first=Pete|last=Williams|date=September 20, 2016|publisher=KWQC-TV|accessdate=September 20, 2016}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{cite web|url=http://kutv.com/news/nation-world/investigators-suspect-wrote-about-boston-bombers-anwar-al-awlaki|title=Investigators: Suspect wrote about Boston bombers, Anwar al-Awlaki|publisher=Sinclair Broadcast Group|accessdate=September 20, 2016|date=September 20, 2016|website=KUTV}}</ref><ref name=" |

A note found on the pressure cooker bomb left on West 27th Street referred to [[Anwar al-Awlaki]] (the Muslim cleric who became a senior member of [[al-Qaeda]] and was then killed by a U.S. drone strike), the Boston Marathon bombings, and the [[2009 Fort Hood shooting]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://kwqc.com/2016/09/20/note-on-pressure-cooker-found-in-manhattan-mentioned-boston-bombing-sources-say/|title=Note on Pressure Cooker Found in Manhattan Mentioned Boston Bombing, Sources Say|first=Pete|last=Williams|date=September 20, 2016|publisher=KWQC-TV|accessdate=September 20, 2016}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{cite web|url=http://kutv.com/news/nation-world/investigators-suspect-wrote-about-boston-bombers-anwar-al-awlaki|title=Investigators: Suspect wrote about Boston bombers, Anwar al-Awlaki|publisher=Sinclair Broadcast Group|accessdate=September 20, 2016|date=September 20, 2016|website=KUTV}}</ref><ref name="FBI"/> |

||

On September 20, investigators said that when Rahami was arrested, he had a notebook in his possession in which he had written about Anwar al-Awlaki and about the Boston Marathon bombers.<ref name="InspiredBinLaden"/><ref name=" |

On September 20, investigators said that when Rahami was arrested, he had a notebook in his possession in which he had written about Anwar al-Awlaki and about the Boston Marathon bombers.<ref name="InspiredBinLaden"/><ref name="FBI"/> The notebook had bullet holes and blood stains. In the notebook, Rahami wrote of "killing the [[Kafir|kuffar]]," an Arabic term for unbelievers.<ref name="InspiredBinLaden" /> |

||

According to authorities, Rahami was not part of a [[terrorist cell]], but was motivated and inspired by the [[Jihadism|extremist Islamic ideology]] espoused by [[al-Qaeda]] founder [[Osama bin Laden]] and al-Qaeda chief propagandist [[Anwar al-Awlaki]].<ref name="InspiredBinLaden"/> The criminal complaint filed against Rahami states that Rahami had a YouTube account in which he listed two jihadist propaganda videos as "favorites" alongside other, unrelated materials.<ref>{{cite web|first=Christopher|last=Mele|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/21/nyregion/ahmad-khan-rahamis-youtube-account-included-jihad-videos-complaint-says.html|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami's YouTube Account Listed Jihad Videos, Complaint Says|work=The New York Times|date=September 20, 2016|accessdate=September 20, 2016}}</ref> |

According to authorities, Rahami was not part of a [[terrorist cell]], but was motivated and inspired by the [[Jihadism|extremist Islamic ideology]] espoused by [[al-Qaeda]] founder [[Osama bin Laden]] and al-Qaeda chief propagandist [[Anwar al-Awlaki]].<ref name="InspiredBinLaden"/> The criminal complaint filed against Rahami states that Rahami had a YouTube account in which he listed two jihadist propaganda videos as "favorites" alongside other, unrelated materials.<ref>{{cite web|first=Christopher|last=Mele|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/21/nyregion/ahmad-khan-rahamis-youtube-account-included-jihad-videos-complaint-says.html|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami's YouTube Account Listed Jihad Videos, Complaint Says|work=The New York Times|date=September 20, 2016|accessdate=September 20, 2016}}</ref> |

||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

| employer = First American Fried Chicken |

| employer = First American Fried Chicken |

||

| known_for = |

| known_for = |

||

| height = {{height|ft=5|in=6}}<ref name="FBI"/> |

|||

| height = {{height|ft=5|in=6}}<ref name="WaPoCharges">{{cite web|first1=Ellen|last1=Nakashima|first2=Matt|last2=Zapotosky|first3=Mark|last3=Berman|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/09/19/bombing-suspect-charged-with-attempted-murder-of-a-law-enforcement-officer-with-further-charges-expected|title=The FBI looked into suspected bomber Ahmad Rahami in 2014 and found no 'ties to terrorism'|date=September 12, 2016|newspaper=Washington Post|access-date=September 28, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

| weight = {{convert|200|lb|kg}}<ref name=" |

| weight = {{convert|200|lb|kg}}<ref name="FBI"/> |

||

| religion = <!-- Religion should be supported with a citation from a reliable source; do not add a religious denomination here --> |

| religion = <!-- Religion should be supported with a citation from a reliable source; do not add a religious denomination here --> |

||

| denomination = <!-- Denomination should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> |

| denomination = <!-- Denomination should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> |

||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

At one time, Rahami was licensed to carry firearms. In August 2014, he, at that time living in [[Perth Amboy, New Jersey]], was charged with [[aggravated assault]] and [[unlawful possession of a weapon]] in [[Union County, New Jersey|Union County]]. The charges arose from allegations that Rahami had stabbed his brother in the leg, after the victim and another brother attempted to stop Rahami from assaulting their mother and sister "for no apparent reason". Rahami was reported by two of his siblings the next day and spent three months in the Union County Jail, but was reported to have [[bail]]ed. A [[grand jury]] declined to make an [[indictment]], and the charges were dropped on September 22.<ref name="KleinfieldFixture" /><ref name="ArkinSiemaszko" /><ref name=NJ.Violence>{{cite web|url=http://www.nj.com/union/index.ssf/2016/09/hold_ahmad_rahami_attacked_sister_stabbed_brother.html|title=Details emerge of Ahmad Khan Rahami's alleged history of violence toward family|work=NJ.com|date=September 28, 2016|accessdate=September 28, 2016|first=Tom|last=Haydon}}</ref> A "high-ranking law enforcement official with knowledge of the investigation" said Rahami had spent two additional days in jail, one in February 2012 for allegedly violating a [[restraining order]], and another in October 2008 for failure to pay traffic tickets.<ref name="KleinfieldFixture" /> Rahami's father Mohammad had tried to contact the FBI about his son around August 2014, but two months later, Rahami was cleared by the FBI. One reason cited was that Mohammad had stated that he was angry about the August domestic incident when he reported his son, so he had denied his previous statement.<ref name="InspiredBinLaden"/><ref name=NJ.Violence/> |

At one time, Rahami was licensed to carry firearms. In August 2014, he, at that time living in [[Perth Amboy, New Jersey]], was charged with [[aggravated assault]] and [[unlawful possession of a weapon]] in [[Union County, New Jersey|Union County]]. The charges arose from allegations that Rahami had stabbed his brother in the leg, after the victim and another brother attempted to stop Rahami from assaulting their mother and sister "for no apparent reason". Rahami was reported by two of his siblings the next day and spent three months in the Union County Jail, but was reported to have [[bail]]ed. A [[grand jury]] declined to make an [[indictment]], and the charges were dropped on September 22.<ref name="KleinfieldFixture" /><ref name="ArkinSiemaszko" /><ref name=NJ.Violence>{{cite web|url=http://www.nj.com/union/index.ssf/2016/09/hold_ahmad_rahami_attacked_sister_stabbed_brother.html|title=Details emerge of Ahmad Khan Rahami's alleged history of violence toward family|work=NJ.com|date=September 28, 2016|accessdate=September 28, 2016|first=Tom|last=Haydon}}</ref> A "high-ranking law enforcement official with knowledge of the investigation" said Rahami had spent two additional days in jail, one in February 2012 for allegedly violating a [[restraining order]], and another in October 2008 for failure to pay traffic tickets.<ref name="KleinfieldFixture" /> Rahami's father Mohammad had tried to contact the FBI about his son around August 2014, but two months later, Rahami was cleared by the FBI. One reason cited was that Mohammad had stated that he was angry about the August domestic incident when he reported his son, so he had denied his previous statement.<ref name="InspiredBinLaden"/><ref name=NJ.Violence/> |

||

Rahami, reportedly, went back to Afghanistan several times (including for an extended period starting in 2012), and "showed signs of [[radicalization]]" afterwards.<ref name="CapturedCNN" /><ref name="HuntforRahami" /><ref name="KleinfieldFixture"/> Rahami and members of his family also made several trips to [[Pakistan]], where they had Afghan relatives living as refugees.<ref name="ArkinSiemaszko" /><ref name=":1">{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/live/2016/sep/19/us-authorities-investigating-new-jersey-explosive-devices-live-updates|title=New York bombings: Ahmad Khan Rahami charged with attempted murder – as it happened|work=The Guardian|date=September 20, 2016|accessdate=September 20, 2016|first1=Haroon|last1=Siddique|first2=Martin|last2=Pengelly|first3=Alan|last3=Yuhas}}</ref> He spent several weeks in the cities of [[Quetta]] and nearby [[Kuchlak]],<ref name=TalibanSeminary>{{cite news|last1=Boone|first1=Jon|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami spent time at Pakistan seminary tied to Taliban|url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/23/ahmad-khan-rahami-pakistan-taliban-new-york-bombing-terrorism|accessdate=September 24, 2016|agency=The Guardian|date=September 23, 2016}}</ref> as well as [[Kandahar, Afghanistan]]. At Quetta, which is home to a large population of [[Afghans in Pakistan|Afghan immigrants]] and some Taliban members-in-exile,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/ahmad-khan-rahami-bombing-suspect-visits-to-pakistan-and-afghanistan-a7317546.html|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami: Bombing suspect's 'personality changed after visits to Pakistan and Afghanistan'|work=The Independent|date=September 20, 2016|accessdate=September 20, 2016|first=Andrew|last=Buncombe}}</ref> he married a Pakistani woman<ref name="WhoIsRahami"/> in July 2011. In Kuchlak, he attended an Afghan-run [[naqshbandi]] [[madrasa|religious seminary]] closely associated with the Taliban movement, where he took lectures in Islamic education for three weeks.<ref name=TalibanSeminary/> Rahami remained in Pakistan from April 2013 to March 2014, and traveled to Afghanistan during the period.<ref name=TalibanSeminary/> Following his near-year-long stay in the region, he underwent additional screening. On both occasions, he stated that he visited family members and was cleared by [[U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement|immigration and customs officials]].<ref name="WhoIsRahami" /><ref name="FBI">{{cite news|title=The FBI looked into suspected bomber Ahmad Rahami in 2014 and found no ‘ties to terrorism’|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/09/19/bombing-suspect-charged-with-attempted-murder-of-a-law-enforcement-officer-with-further-charges-expected/ |

Rahami, reportedly, went back to Afghanistan several times (including for an extended period starting in 2012), and "showed signs of [[radicalization]]" afterwards.<ref name="CapturedCNN" /><ref name="HuntforRahami" /><ref name="KleinfieldFixture"/> Rahami and members of his family also made several trips to [[Pakistan]], where they had Afghan relatives living as refugees.<ref name="ArkinSiemaszko" /><ref name=":1">{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/live/2016/sep/19/us-authorities-investigating-new-jersey-explosive-devices-live-updates|title=New York bombings: Ahmad Khan Rahami charged with attempted murder – as it happened|work=The Guardian|date=September 20, 2016|accessdate=September 20, 2016|first1=Haroon|last1=Siddique|first2=Martin|last2=Pengelly|first3=Alan|last3=Yuhas}}</ref> He spent several weeks in the cities of [[Quetta]] and nearby [[Kuchlak]],<ref name=TalibanSeminary>{{cite news|last1=Boone|first1=Jon|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami spent time at Pakistan seminary tied to Taliban|url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/23/ahmad-khan-rahami-pakistan-taliban-new-york-bombing-terrorism|accessdate=September 24, 2016|agency=The Guardian|date=September 23, 2016}}</ref> as well as [[Kandahar, Afghanistan]]. At Quetta, which is home to a large population of [[Afghans in Pakistan|Afghan immigrants]] and some Taliban members-in-exile,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/ahmad-khan-rahami-bombing-suspect-visits-to-pakistan-and-afghanistan-a7317546.html|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami: Bombing suspect's 'personality changed after visits to Pakistan and Afghanistan'|work=The Independent|date=September 20, 2016|accessdate=September 20, 2016|first=Andrew|last=Buncombe}}</ref> he married a Pakistani woman<ref name="WhoIsRahami"/> in July 2011. In Kuchlak, he attended an Afghan-run [[naqshbandi]] [[madrasa|religious seminary]] closely associated with the Taliban movement, where he took lectures in Islamic education for three weeks.<ref name=TalibanSeminary/> Rahami remained in Pakistan from April 2013 to March 2014, and traveled to Afghanistan during the period.<ref name=TalibanSeminary/> Following his near-year-long stay in the region, he underwent additional screening. On both occasions, he stated that he visited family members and was cleared by [[U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement|immigration and customs officials]].<ref name="WhoIsRahami" /><ref name="FBI">{{cite news|title=The FBI looked into suspected bomber Ahmad Rahami in 2014 and found no ‘ties to terrorism’|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/09/19/bombing-suspect-charged-with-attempted-murder-of-a-law-enforcement-officer-with-further-charges-expected/|accessdate=29 September 2016|publisher=The Washington Post|date=September 20, 2016|first1=Ellen|last1=Nakashima|first2=Matt|last2=Zapotosky|first3=Mark|last3=Berman}}</ref> The FBI did not find any signs of ties to terrorism during background checks.<ref name="FBI"/> |

||

According to a childhood friend, Rahami grew a beard, started wearing more religious clothing following his trips to Afghanistan, and began praying in the back of his family's restaurant.<ref name=Yahoo.Recalls/><ref name=Reuters.Clashed/> When the mobile phone from West 27th Street was examined, investigators found that Rahami had posted [[Jihadism|jihadist]] writings on various websites,<ref name="Weiss Rizzi Kapp Gardiner 2016" /> but it was "not known whether he had any links to an overseas terror organization, or whether he had been inspired by such organizations and their propaganda efforts, as others have been."<ref name="HuntforRahami" /> One intelligence source said Rahami may have self-radicalized.<ref name="FBI"/> |

According to a childhood friend, Rahami grew a beard, started wearing more religious clothing following his trips to Afghanistan, and began praying in the back of his family's restaurant.<ref name=Yahoo.Recalls/><ref name=Reuters.Clashed/> When the mobile phone from West 27th Street was examined, investigators found that Rahami had posted [[Jihadism|jihadist]] writings on various websites,<ref name="Weiss Rizzi Kapp Gardiner 2016" /> but it was "not known whether he had any links to an overseas terror organization, or whether he had been inspired by such organizations and their propaganda efforts, as others have been."<ref name="HuntforRahami" /> One intelligence source said Rahami may have self-radicalized.<ref name="FBI"/> |

||

| Line 203: | Line 203: | ||

===State and federal prosecutions=== |

===State and federal prosecutions=== |

||

On the night of September 19, Rahami was charged in [[New Jersey Superior Court]] with five counts of [[attempted murder]] of a law enforcement officer in relation to the shootout in Linden. He was also charged with second-degree [[unlawful possession of a weapon]] and second-degree possession of a weapon for an unlawful purpose, both in relation to the handgun found in his possession.<ref name=" |

On the night of September 19, Rahami was charged in [[New Jersey Superior Court]] with five counts of [[attempted murder]] of a law enforcement officer in relation to the shootout in Linden. He was also charged with second-degree [[unlawful possession of a weapon]] and second-degree possession of a weapon for an unlawful purpose, both in relation to the handgun found in his possession.<ref name="FBI"/><ref name=WABC.Charged/><ref name=WashPost.Arrested/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theatlantic.com/news/archive/2016/09/explosion-chelsea-new-york/500498/|title=What We Know: The Explosions in New York and New Jersey|work=The Atlantic|date=September 19, 2016|accessdate=September 19, 2016|first1=Matt|last1=Ford|first2=Krishnadev|last2=Calamur|first3=Marina|last3=Koren|first4=Matt|last4=Vasilogambros}}</ref> |

||

Under New Jersey state law, all criminal defendants were eligible for [[bail]], before 2017.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Ford|first1=James|title=Why the $5.2M bail set for Ahmad Khan Rahami doesn’t mean he’ll walk|url=http://pix11.com/2016/09/20/bail-for-nj-ny-bombing-suspect-ahmad-khan-rahami-set-at-5-2m/|accessdate=21 September 2016|publisher=pix11.com|date=September 20, 2016}}</ref> Rahami's bail was set at $5.2 million.<ref name=Independent.Held>{{cite web|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/new-york-explosion-bomb-blast-live-2016-manhattan-chelsea-bombing-latest-news-updating-a7314361.html|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami: Suspect held on five attempted murder charges of cops and $5.2 million bail – live updates|work=The Independent|date=September 19, 2016|accessdate=September 19, 2016|first1=Adam|last1=Withnall|first2=Samuel|last2=Osborne|first3=Rachel|last3=Revesz|first4=Justin|last4=Carissimo}}</ref> |

Under New Jersey state law, all criminal defendants were eligible for [[bail]], before 2017.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Ford|first1=James|title=Why the $5.2M bail set for Ahmad Khan Rahami doesn’t mean he’ll walk|url=http://pix11.com/2016/09/20/bail-for-nj-ny-bombing-suspect-ahmad-khan-rahami-set-at-5-2m/|accessdate=21 September 2016|publisher=pix11.com|date=September 20, 2016}}</ref> Rahami's bail was set at $5.2 million.<ref name=Independent.Held>{{cite web|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/new-york-explosion-bomb-blast-live-2016-manhattan-chelsea-bombing-latest-news-updating-a7314361.html|title=Ahmad Khan Rahami: Suspect held on five attempted murder charges of cops and $5.2 million bail – live updates|work=The Independent|date=September 19, 2016|accessdate=September 19, 2016|first1=Adam|last1=Withnall|first2=Samuel|last2=Osborne|first3=Rachel|last3=Revesz|first4=Justin|last4=Carissimo}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:45, 29 September 2016

| 2016 New York and New Jersey bombings | |

|---|---|

| |

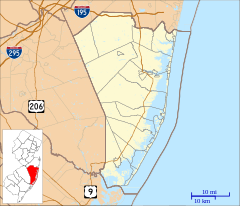

Locations of the bombings Locations of the bombings Locations of the bombings Locations of the bombings | |

| Location | Seaside Park, New Jersey, U.S. Chelsea, Manhattan, New York, U.S. Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S. Linden, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 39°55′32″N 74°04′29″W / 39.925602°N 74.074726°W (Seaside Park) 40°44′37″N 73°59′40″W / 40.743631°N 73.994308°W (Manhattan) 40°40′04″N 74°12′54″W / 40.667778°N 74.215°W (Elizabeth) |

| Date | Seaside Park bombing: September 17, 2016, 9:30 a.m. Manhattan bombing: September 17, 2016, 8:31 p.m. Elizabeth bombs discovered: September 19, 2016, c. 12:40 a.m. Linden shootout: September 19, 2016, 11:23 a.m. (All times are UTC-04:00) |

Attack type | Bombing, shootout |

| Weapons | Pressure cooker bombs, pipe bombs, handgun |

| Deaths | 0 |

| Injured | 35 total:

|

On September 17–19, 2016, there were four bombings or bombing attempts in the New York metropolitan area, specifically in Seaside Park, New Jersey; Manhattan, New York; and Elizabeth, New Jersey.

On September 17, at about 9:30 a.m., a pipe bomb exploded in a trash can along the route of a United States Marine Corps charity run in Seaside Park. No one was injured. Later that day, at about 8:30 p.m., a homemade pressure cooker bomb exploded on West 23rd Street in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. Thirty-one civilians were injured, 24 of whom were taken to the hospital. A second pressure cooker bomb, with wires and a mobile phone attached, was discovered by authorities on West 27th Street, four blocks away. Late on September 18, multiple bombs were discovered inside a suspicious package at the Elizabeth train station. One of those bombs detonated early the next day during the police investigation, and no injuries were reported.

On September 19, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) identified Ahmad Khan Rahami as a suspect in all of the incidents. He was captured hours later after a shootout in Linden, New Jersey. The shootout left Rahami and three police officers injured. Rahami was hospitalized and charged with crimes in both New Jersey state court (including attempted murder of two law enforcement officers) and federal court (including bombing and use of a destructive device).

According to authorities, Rahami was not part of a terrorist cell, but was motivated and inspired by the extremist Islamic ideology espoused by al-Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda chief propagandist Anwar al-Awlaki.

Seaside Park bombing

In the morning of September 17, 2016, in Ocean County, New Jersey, the Seaside Semper Five, a 5k run event, was expected to draw as many as 3,000 people, with many of them being veterans of the United States Armed Forces. The race was delayed after a suspicious backpack was noticed in the vicinity of the starting point.[1][2]

At about 9:30 a.m., shortly before the race was supposed to start, a pipe bomb exploded in a trash can on Ocean Avenue in Seaside Park.[1][2] Three "rudimentary" pipe bombs, all reportedly timed to go off during the race, were later found, with only one of the three having exploded. No one was hurt by this bombing, however.[3]

The race was canceled after the explosion,[3] and the beach and boardwalk in Seaside Park were evacuated. Police officials and federal agents soon went door-to-door, asking residents about information regarding the bombs or any suspicious activity they may have seen, heard, or witnessed.[4][5]

Manhattan bombing

On the same day as the Seaside Park bombing, a pressure cooker bomb filled with shrapnel, in the form of small bearings or metal BBs,[6] exploded in a crowded area on West 23rd Street, between Sixth Avenue and Seventh Avenue at 8:31 p.m.[1][6][7] The explosion occurred in front of 133 West 23rd Street[8] in the vicinity of a construction site,[9] at which materials were in place for exterior renovations of the Visions at Selis Manor facility, an apartment building for the blind, at 135 West 23rd Street.[10][11] Other nearby buildings included the Townhouse Inn of Chelsea,[11] many restaurants, and a Trader Joe's at 21st Street and 6th Avenue.[10] The Chelsea neighborhood is residential, known for its nightlife, and is not close to any significant tourist sites or government buildings.[12]

Witnesses said that the explosion "seemed to have started inside a sidewalk dumpster" in the vicinity of Sixth Avenue, and photographs of a "twisted dumpster" in the middle of West 23rd Street went viral on Twitter.[1] A law enforcement official speaking on condition of anonymity stated that the explosion "appeared to have come from a construction toolbox" in front of a building, and photographs of the area reportedly showed a twisted, crumpled black metal box.[10]

Effects

The explosion "was powerful enough to vault a heavy steel Dumpster more than 120 feet through the air ... Windows shattered 400 feet from where the explosion went off, and pieces of the bomb were recovered 650 feet away."[13] The explosion caused damage to a nearby five-story brownstone,[1] and debris was strewn in front of the St. Vincent de Paul Church.[14] The moment of the blast was captured on closed-circuit television footage from three cameras.[15]

Thirty-one civilians were injured,[13] 24 of whom were taken to four local hospitals.[14][16] Most injuries were scrapes and bruises caused by flying debris and glass.[10][15] None of the injuries were life-threatening, but one victim sustained a puncture wound and was seriously hurt.[1] Nine of the injured were taken to Bellevue Hospital,[17] including the seriously injured civilian.[14] Lenox Health Greenwich Village treated another nine victims.[9] By the following morning, all of the injured had been released.[6][8]

The explosion disrupted travel in Manhattan extensively. A significant zone (14th Street to 34th Street between Fifth Avenue and Eighth Avenue) was closed to car travel overnight. By 7:00 a.m. the following morning, "all of the streets and avenues had been reopened, except for West 23rd Street, which remained closed between Fifth and Eighth Avenues." New York City Subway service to stations along West 23rd Street was disrupted while the investigation was ongoing.[18]

Discovery of second device

Following the explosion, officers began a block-by-block search for additional unexploded bombs.[19] Several hours later, police received a 9-1-1 call from a resident of West 27th Street who had seen a suspicious-looking package near her home. The device was under a mailbox at West 27th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, four blocks away from the site of the original blast.[20] When authorities came to look, two state troopers discovered the pressure cooker bomb concealed in a plastic bag and connected with dark wiring to a mobile phone.[6][19] The bomb was filled with small bearings or metal BBs.[6] The pressure cooker bomb was described as similar to those used in the Boston Marathon bombing.[1][14][16][21][22] The New York City Police Department (NYPD) reported its find of a "possible secondary device" at 11:00 p.m.[1]

The bomb was removed by an NYPD bomb squad robot.[1][10] The robot placed the bomb in a containment chamber, and the device was driven away at around 2:25 a.m. on September 18.[19] Investigators obtained fingerprints and the mobile phone from the device.[23][24] The bomb was driven to the NYPD's Rodman's Neck firing range in the Bronx, where it was rendered safe[8] via a controlled explosion.[23] The devices were to be sent to the FBI Laboratory in Quantico, Virginia, for further inspection.[8][9]

Discovery of bombs in Elizabeth

At around 8:00 p.m. on September 18, two men took a backpack atop a municipal garbage can at the Elizabeth train station in Elizabeth, New Jersey.[24][25][26][27][28] One of the men, Lee Parker, was homeless and was looking for a backpack so he could go to a job search. His friend Ivan White had found the backpack above the garbage can.[29][30] They were about 300 feet (91 m) from a busy pub's front entrance[25] and about 500 feet (150 m) from a train trestle when they took the backpack.[23] White and Parker looked into the backpack, discovered that the item contained wires and a pipe, and called 9-1-1 at around 8:45 p.m.[26][29][30] The men, who were not held as suspects,[24][26] were hailed as heroes in Elizabeth;[29][30] a GoFundMe campaign in their name raised over $16,000 in donations.[31]

The Elizabeth Police Department was the first authority to respond to the men's 9-1-1 call.[29][30] The investigation was soon turned over to the New Jersey State Police and the FBI, which sent in two robots that confirmed the devices were pipe bombs. One of these bombs was accidentally detonated at around 12:40 a.m. as the robots sought to disarm the devices. One robot was "destroyed" by the blast, while the other robot's mechanical arm was broken.[26][28] Authorities were working to disable the other devices.[26][32] Following the bomb's accidental explosion, the station was evacuated. The surrounding area was put on lockdown, and service was suspended between the Newark Airport and Elizabeth stations for the day. New Jersey-bound trains from New York were held at Penn Station.[27][33]

Elizabeth Mayor J. Christian Bollwage said that it was unclear whether the train station was a specific target, or whether the bombs were dumped by someone looking to quickly get rid of them.[26] The Elizabeth device was "similar in appearance" to the Seaside Park device.[25] Police later theorized that the bomber, Ahmad Khan Rahami, had thrown away the bombs in Elizabeth in an effort to hide the evidence because these bombs lacked detonators.[24]

Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF), Homeland Security, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) responded to the scene of the Chelsea bombing and were involved in the investigation, in addition to the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) and the NYPD. Initially, the Seaside Park and Manhattan bombings were investigated as separate incidents, but over a period of two days, the investigation yielded similarities between the two incidents, leading the investigators to determine that they were connected, and therefore that it was to be investigated as one overall composite terrorist act or endeavor, committed by the same party.[1][17][34]

Within hours after the attack, officials determined that the explosion was intentional, and ruled out the possibility of a natural gas explosion.[1][35] Investigators did not immediately find evidence of a terrorism link,[1][16] initially leaving open the possibility of arson or vandalism at the time.[36] A link to terrorism was discovered in the following days.[37][38]

Both of the Manhattan bombs—the one that exploded and the second that was disabled—were of the same design, using pressure cookers filled with bearings or metal BBs that were rigged with flip phones and Christmas lights that set off a small charge of hexamethylene triperoxide diamine (HMTD), which served as a detonator for a larger charge of a secondary explosive similar to Tannerite.[37][39]

The FBI examined fingerprints from the undetonated West 27th Street pressure cooker bomb and its attached mobile phone.[23] DNA evidence was also recovered.[38] On September 19, the FBI traced the prints, as well as some pictures on the mobile phone, to Ahmad Khan Rahami (see below).[24][37]

Though the explosives in all four incidents were of three different designs, the Department of Homeland Security found that the bomb-maker followed guidelines featured in Inspire, an online magazine published by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[40]

Search for suspects

Investigators discovered surveillance video that showed a suspect planting a bomb, later identified as Rahami, on West 23rd Street in Manhattan, then walking to West 27th Street dragging a duffel bag. The subject left the bag at West 27th Street. Later, two individuals took the pressure cooker bomb out of the bag and left the scene.[22][41] Authorities determined that the two men who had taken the bomb out of the bag were, most likely, scavengers who had only wanted the duffel bag and did not know what they had been handling; in the process, they might have deactivated the bomb in the bag. The NYPD and FBI wished to talk with these men, who were considered possible witnesses but were not suspected in helping plant the bomb.[24][42]

Late on September 18, the day after the Manhattan explosion, the FBI announced that five men, who were later found to be relatives of Rahami, had been detained in connection with the investigation. The men were detained at about 8:45 p.m. at a traffic stop, which was being conducted by the FBI and NYPD on the Belt Parkway near the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge.[25][37][43][44][45]

Motive

An official speaking to The New York Times on condition of anonymity said, "We don't understand the target or the significance of it. It's by a pile of dumpsters on a random sidewalk."[1] At a news conference the day following the Manhattan explosion, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said that placing a bomb in a crowded city street was intrinsically a terrorist act, but that "there is no evidence of an international terrorism connection with this incident," while noting that the investigation was still in its early stages.[41] An explosives expert, speaking anonymously, said the materials used in the bomb indicated that the bomb-builder had some knowledge of how to assemble the explosive device.[6]

A note found on the pressure cooker bomb left on West 27th Street referred to Anwar al-Awlaki (the Muslim cleric who became a senior member of al-Qaeda and was then killed by a U.S. drone strike), the Boston Marathon bombings, and the 2009 Fort Hood shooting.[46][47][38]

On September 20, investigators said that when Rahami was arrested, he had a notebook in his possession in which he had written about Anwar al-Awlaki and about the Boston Marathon bombers.[13][38] The notebook had bullet holes and blood stains. In the notebook, Rahami wrote of "killing the kuffar," an Arabic term for unbelievers.[13]

According to authorities, Rahami was not part of a terrorist cell, but was motivated and inspired by the extremist Islamic ideology espoused by al-Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda chief propagandist Anwar al-Awlaki.[13] The criminal complaint filed against Rahami states that Rahami had a YouTube account in which he listed two jihadist propaganda videos as "favorites" alongside other, unrelated materials.[48]

Suspect

Ahmad Khan Rahami | |

|---|---|

احمد خان رحامی | |

Surveillance image of Ahmad Khan Rahami, who was arrested following a manhunt | |

| Born | January 23, 1988 |

| Citizenship | American |

| Education | Edison High School |

| Employer | First American Fried Chicken |

| Height | 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m)[38] |

| Criminal charges |

|

| Criminal status | In-custody |

| Children | 1[54] |

Background

Ahmad Khan Rahami (born January 23, 1988), an Afghan American,[24][37] came to the United States from Afghanistan in 2000,[55] and was naturalized in 2011. His father, Mohammad Rahami, came to the U.S. several years earlier seeking asylum.[54] According to a neighbor, Rahami's father had been part of the anti-Soviet mujahideen movement in Afghanistan, and was critical of the Taliban.[56] The younger Rahami may have as many as seven siblings.[37][55] He graduated from Edison High School in 2008.[57] From 2010 to 2012, he attended Middlesex County College in Edison, New Jersey, majoring in criminal justice. He did not graduate.[54][57]

Rahami's friends described him as a generous person who invited his friends to eat and conduct rap battles at his family's fried chicken restaurant—First American Fried Chicken in Elizabeth, 15 miles (24 km) from New York City. To some, he was known as Mad, short for Ahmad. In recent years, though, he seemed to be a "completely different person" who was more stern than before and less easygoing.[56][58] A classmate from Edison High described him as quiet, mild-mannered, well-dressed, and "not abrasive, [but] funny" whenever he spoke.[58]

The Rahami family had a history of disputes with the City of Elizabeth over the restaurant's operating hours, claiming that the city was discriminating against them because of their ethnicity and because they were Muslim.[37][54][59] They filed a lawsuit against the city in 2011, in which they alleged harassment and religious discrimination by police and officials who would force them to close early. Mayor J. Christian Bollwage said the longstanding issues were caused by a series of complaints from neighbors, who reported noise and large crowds gathering at the restaurant late at night. The city later barred all takeout restaurants, including the Rahamis', from operating past 10:00 p.m. In 2009, two members of Rahami's family were arrested for attempting to record a conversation with police, according to court papers.[60][61][62] Rahami lived above the restaurant with his family.[56]

At one time, Rahami was licensed to carry firearms. In August 2014, he, at that time living in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, was charged with aggravated assault and unlawful possession of a weapon in Union County. The charges arose from allegations that Rahami had stabbed his brother in the leg, after the victim and another brother attempted to stop Rahami from assaulting their mother and sister "for no apparent reason". Rahami was reported by two of his siblings the next day and spent three months in the Union County Jail, but was reported to have bailed. A grand jury declined to make an indictment, and the charges were dropped on September 22.[56][57][63] A "high-ranking law enforcement official with knowledge of the investigation" said Rahami had spent two additional days in jail, one in February 2012 for allegedly violating a restraining order, and another in October 2008 for failure to pay traffic tickets.[56] Rahami's father Mohammad had tried to contact the FBI about his son around August 2014, but two months later, Rahami was cleared by the FBI. One reason cited was that Mohammad had stated that he was angry about the August domestic incident when he reported his son, so he had denied his previous statement.[13][63]

Rahami, reportedly, went back to Afghanistan several times (including for an extended period starting in 2012), and "showed signs of radicalization" afterwards.[23][37][56] Rahami and members of his family also made several trips to Pakistan, where they had Afghan relatives living as refugees.[57][64] He spent several weeks in the cities of Quetta and nearby Kuchlak,[65] as well as Kandahar, Afghanistan. At Quetta, which is home to a large population of Afghan immigrants and some Taliban members-in-exile,[66] he married a Pakistani woman[54] in July 2011. In Kuchlak, he attended an Afghan-run naqshbandi religious seminary closely associated with the Taliban movement, where he took lectures in Islamic education for three weeks.[65] Rahami remained in Pakistan from April 2013 to March 2014, and traveled to Afghanistan during the period.[65] Following his near-year-long stay in the region, he underwent additional screening. On both occasions, he stated that he visited family members and was cleared by immigration and customs officials.[54][38] The FBI did not find any signs of ties to terrorism during background checks.[38]

According to a childhood friend, Rahami grew a beard, started wearing more religious clothing following his trips to Afghanistan, and began praying in the back of his family's restaurant.[58][61] When the mobile phone from West 27th Street was examined, investigators found that Rahami had posted jihadist writings on various websites,[24] but it was "not known whether he had any links to an overseas terror organization, or whether he had been inspired by such organizations and their propaganda efforts, as others have been."[37] One intelligence source said Rahami may have self-radicalized.[38]

In June 2016, Rahami's wife left for Pakistan,[67] planning to return September 21.[68] On September 19, following her husband's arrest, she was stopped by the United Arab Emirates authorities. Two days later, she returned to New York and was questioned by the investigators.[67] The wife was cooperative and not accused of wrongdoing.[69]

In July 2016, Rahami passed the required background check and legally purchased the Glock 9 mm handgun he used in the shootout, from a licensed dealer in Salem, Virginia.[70]

Manhunt, shootout, and arrest

After stopping the five men on the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge, FBI agents and Elizabeth police searched Rahami's home in the early morning of September 18.[37][54] The FBI asked for public assistance in detaining Rahami for questioning in connection with the bombings in Manhattan and Seaside Park, as well as the attempted overnight bombing in Elizabeth. The bureau considered him to be armed and dangerous.[37]

At 7:39 a.m. on September 19, the NYPD posted a "Wanted" poster of Rahami on Twitter.[71] Seventeen minutes later, the Wireless Emergency Alert system was used to send an alert message to the mobile phones of millions of people in New York City, marking the first time New York City used the emergency alert to search for a named suspect.[71][72] The alert message read, "WANTED: Ahmad Khan Rahami, 28-yr-old male. See media for pic. Call 9-1-1 if seen."[72] Mayor de Blasio said, "Anyone who sees this individual or knows anything about him or his whereabouts needs to call it in right away." Authorities stated that Rahami might be armed and dangerous.[64][71][73]

Law enforcement put Rahami on some terror watchlists to prevent him from leaving the United States.[23]

Concurrently, authorities started searching Rahami's home in Elizabeth. The New Jersey State Police released two tweets, one at 9:30 a.m. and the other at 10:56 a.m., both stating that Rahami was wanted in connection with the Seaside Park and Elizabeth bombs.[71] At around 10:30 a.m., a Linden bar owner was in a deli across the street from his bar, watching CNN, when he saw a man sleeping in the bar's doorway. He recognized the man as Rahami from news reports and called 9-1-1, saying "the guy looks a little suspicious and doesn't look good to me."[23][74] When Linden police arrived fifteen minutes later and awoke the man, the officers—who were subsequently identified as Angel Padilla, Peter Hammer, and Mark Kahana[75]—realized that the man was Rahami.[37][51]

Officer Padilla ordered Rahami to show his hands.[75] Rahami disregarded the order,[75] retrieved a Glock 9 mm handgun,[70] and shot Padilla in the abdomen, striking the bulletproof vest.[75] Officer Padilla returned fire, and Rahami fled, with police pursuing him.[37] Rahami fired back indiscriminately.[49] He encountered Officer Hammer seated in his vehicle and fired into the windshield;[13] Hammer was grazed in the head and struck by flying glass from the bullet through the windshield, then he was shot in his hand.[75] In addition, Officer Kahana experienced high blood pressure stemming from the incident.[75] None of the officers' injuries was serious.[23][49][64] During the shootout, Rahami was shot at least seven times, hit in an artery,[76] and sustained a shoulder wound.[23][37][49] He was finally arrested, shortly before noon, and transported to University Hospital by ambulance.[23][37][45][49] He underwent surgery and was in critical but stable condition.[51][77] Officer Padilla was released from the hospital that night, and Officer Hammer was released the next morning.

Following Rahami's arrest, investigators said there was "no indication" he was part of a broader terror cell,[51] nor that such a cell was "operating in the area."[62] Rahami was said to be initially uncooperative during interrogations.[23]

The day after his arrest, Rahami's estranged ex-girlfriend Maria Mena, with whom he had a daughter, filed a petition in a New Jersey state court seeking full custody of the child, citing Rahami as being a possible participant in "terrorist related activity" in New York City. She also filed to change her child's name, as well as to force the media not to contact her or her daughter. The petition for custody was granted the following day, though the request to change the daughter's name was denied, as was the request for media not to contact her, because "the court said it had no authority to grant the requests." Rahami and the mother of his child had engaged in a long-running battle, as Rahami owed Mena more than $3,000 in child support in 2015; Mena had previously gotten a restraining order against Rahami.[78][79]

State and federal prosecutions

On the night of September 19, Rahami was charged in New Jersey Superior Court with five counts of attempted murder of a law enforcement officer in relation to the shootout in Linden. He was also charged with second-degree unlawful possession of a weapon and second-degree possession of a weapon for an unlawful purpose, both in relation to the handgun found in his possession.[38][49][62][80]

Under New Jersey state law, all criminal defendants were eligible for bail, before 2017.[81] Rahami's bail was set at $5.2 million.[50]

On September 20, Rahami was charged in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in Manhattan, by criminal complaint, with four federal crimes including use of weapons of mass destruction (count one); bombing a place of public use (count two); destruction of property by means of fire or explosives (count three); and use of a destructive device during and in furtherance of a crime of violence (count four).[52] On the same day, the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey in Newark charged him with use of a weapon of mass destruction (counts one and two), bombings of a place of public use and public transportation system (count three), and attempted destruction of property by means of fire or explosive (count four).[53][82]

On September 26, Rahami's father and wife both retained the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to defend him on the federal charges. The ACLU will represent Rahami until he is given a federal public defender or other lawyer.[83]

Response

Governor Cuomo released a statement following the Chelsea blast, saying: "We are closely monitoring the situation and urge New Yorkers to, as always, remain calm and vigilant."[1] The day following the bombing, Cuomo and de Blasio toured the damage together.[6]

Hamdullah Mohib, Afghanistan's ambassador to the U.S., released a statement saying the Afghan government condemned the bombings and promising the country's cooperation with the investigation.[62]

In a statement, the Council on American-Islamic Relations welcomed the arrest of Rahami, saying, "American Muslims, like all Americans, reject extremism and violence, and seek a safe and secure nation. Our nation is most secure when we remain united and reject the fear-mongering and guilt by association often utilized following such attacks."[62]

Security was boosted across New York City's five boroughs as a precaution.[16] Cuomo said that, while there was no ongoing threat, he would deploy 1,000 additional National Guard troopers and State Police officers to major commuter hubs during the United Nations General Assembly meeting which began when the bombings were unfolding.[6][23]

In the two days following the Chelsea bombing, the NYPD received 406 phone calls reporting suspicious packages in the city. None were found to contain bombs.[84]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mele, Christopher; Baker, Al; Barbaro, Michael (September 17, 2016). "Powerful Blast Injures at Least 29 in Manhattan; Second Device Found". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Davis, Tom (September 18, 2016). "Pipe Bomb Explodes Along 5K Seaside Park Racecourse on Jersey Shore". Patch.com. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Perez, Evan; Procupecz, Simon; Newsome, John (September 18, 2016). "Blast near Marine Corps race in New Jersey probed as possible terror act". CNN. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ "Beaches reopened but lots of questions after Jersey Shore explosion". Fox29.com. September 18, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ "Seaside Park beaches reopen after pipe bomb blast". News 12 New Jersey. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Santora, Marc; Rashbaum, William K.; Baker, Al; Goldman, Adam (September 18, 2016). "Manhattan Bombs Provide Trove of Clues; F.B.I. Questions 5 People". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Zauderer, Alyssa; Mannarino, Dan (September 18, 2016). "Surveillance videos from Chelsea gym show terrifying moment bomb detonates". WPIX-TV. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Workman, Karen; Rosenberg, Eli; Mele, Christopher (September 18, 2016). "Chelsea Explosion: What We Know and Don't Know". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Bump, Philip; Berman, Mark; Wang, Amy B.; Zapotosky, Matt (September 18, 2016). "Explosion that injured 29 in New York 'obviously an act of terrorism,' governor says". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Investigation underway into NYC explosion that injured 29". Mercury News. Associated Press. September 18, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "De Blasio: Dozens injured in Manhattan explosion". Newsday. September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ "Several injured in 'intentional' New York explosion". Today. September 18, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Santora, Marc; Goldman, Adam (September 21, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami Was Inspired by Bin Laden, Charges Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Sandoval, Edgar; Hensley, Nicole; Otis, Ginger Adams; Parascandola, Rocco; Schapiro, Rich (September 18, 2016). "Explosive fireball rattles Chelsea street injuring 29, secondary pressure cooking device found blocks away". The New York Daily News. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Shallwani, Pervaiz; Vilensky, Mike (September 18, 2016). "'Intentional' Explosion in Chelsea Neighborhood of New York Injures Dozens". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Simon, Mallory; Hume, Tim (September 17, 2016). "New York explosion that injured 29 was 'intentional act,' mayor says". CNN. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Dienst, Jonathan; Winter, Tom; Esposito, Richard; Saliba, Emmanuelle; Helsel, Phil; Fieldstadt, Elisha (September 18, 2016). "'An Act of Terrorism': Investigators Hunting for Clues in NYC Bomb That Injured 29". NBC News. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Mele, Christopher (September 18, 2016). "Explosion Causes Extensive Disruptions to Travel in Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Golstein, Joseph (September 18, 2016). "How Police Found Second Bomb, and a 'Total Containment Vessel' Hauled It Away". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Hurowitz, Noah (September 19, 2016). "Woman Who Found Second Bomb in Chelsea Thought It Was a Science Experiment". DNAinfo New York. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Noah (September 17, 2016). "NYC blast believed to be 'intentional act,' mayor says". NJ.com. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Perez, Evan; Prokupecz, Shimon (September 18, 2016). "New York bombing: Investigators search for suspects, motive". CNN. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Perez, Evan; Prokupecz, Shimon; Grinberg, Emanuella; Yan, Holly (September 19, 2016). "NY, NJ bombings: Suspect charged with attempted murder of officers". CNN. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Weiss, Murray; Rizzi, Nicholas; Kapp, Trevor; Gardiner, Aidan (September 19, 2016). "Thieves Helped Crack the Chelsea Bombing Case, Sources Say". DNAinfo New York. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Almaguer, Miguel; Johnson, Alex; Winter, Tom; Dienst, Jonathan; Siemaszko, Corky (September 19, 2016). "Ahmad Rahami, Suspect in N.Y., N.J. Bombings, in Custody: Sources". NBC News. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Schweber, Nate; Bromwich, Jonah Engel (September 19, 2016). "Pipe Bombs Found Near Train Station in Elizabeth, N.J." The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Dienst, Jonathan; Siff, Andrew; Siegal, Ida; Creag, Katherine; Bordonaro, Lori (September 19, 2016). "Device Explodes Near Train Station in New Jersey as Authorities Probe Bag". NBC New York. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b "Man sought by FBI in N.J., NYC explosions worked in family eatery". NJ.com. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Homeless man, friend who found bombs in Elizabeth say they were 'just doing the right thing'". ABC7 New York. WABC. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Two Men Unlikely Heroes After Discovering Bag Of Pipe Bombs In Elizabeth". CBS New York. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Dimon, Laura; Schapiro, Rich (September 21, 2016). "Online campaign raises more than $16G for two men that discovered backpack full of bombs at N.J. train station". The New York Daily News. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Latest: Man Being Sought Lived in Apartment FBI Searched". ABC News. Associated Press. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ "The Latest: Suspicious Device Checked at NJ Train Station". ABC News. Associated Press. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Hunt, Elle; Yuhas, Alan (September 18, 2016). "New York explosion: Cuomo says 'no evidence of international terrorism' – as it happened". The Guardian. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Eversley, Melanie; McCoy, Kevin (September 17, 2016). "Big blast, 29 injuries in NYC; pressure cooker device removed nearby". USA Today. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ David, Javier E. (September 17, 2016). "NYC Mayor DeBlasio: Chelsea explosion 'intentional', but no immediate terror link". CNBC. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Santora, Marc; Rashbaum, William K.; Baker, Al; Goldman, Adam (September 18, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami Is Arrested in Manhattan and New Jersey Bombings". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nakashima, Ellen; Zapotosky, Matt; Berman, Mark (September 20, 2016). "The FBI looked into suspected bomber Ahmad Rahami in 2014 and found no 'ties to terrorism'". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Greenemeier, Larry (September 19, 2016). "Chemicals Could Be a Key in Investigating the New York and New Jersey Bombings". Scientific American. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Silverstein, Jason (September 25, 2016). "Ahmad Rahami may have followed bomb-making tips from Al Qaeda magazine, memo shows". The New York Daily News. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Parascandola, Rocco; Durkin, Erin; Otis, Ginger Adams (September 18, 2016). "Authorities hunt for terrorists who caused Chelsea explosion and planned to detonate second bomb". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Celona, Larry; Musumeci, Natalie (September 19, 2016). "Two scavengers took second bomb out of suitcase in Chelsea". New York Post. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Katersky, Aaron; Crudele, Mark; Levine, Mike; Caplan, David (September 18, 2016). "Sources: Up to 5 People in FBI Custody in Connection With NY Bombing, After Traffic Stop". Yahoo! GMA. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Celona, Larry (September 18, 2016). "FBI detains 5 in connection to Chelsea bombing". The New York Post. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Sandoval, Edgar; Marcius, Chelsia Rose; Rayman, Graham (September 19, 2016). "Cops arrest New Jersey resident Ahmad Khan Rahami, wanted for NYC and N.J. bombings, after he shoots police officer". The New York Daily News. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Williams, Pete (September 20, 2016). "Note on Pressure Cooker Found in Manhattan Mentioned Boston Bombing, Sources Say". KWQC-TV. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ "Investigators: Suspect wrote about Boston bombers, Anwar al-Awlaki". KUTV. Sinclair Broadcast Group. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ Mele, Christopher (September 20, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami's YouTube Account Listed Jihad Videos, Complaint Says". The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bombing Suspect Ahmad Khan Rahami Captured in Linden, Charged With 5 Counts Attempted Murder". WABC-TV. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Withnall, Adam; Osborne, Samuel; Revesz, Rachel; Carissimo, Justin (September 19, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami: Suspect held on five attempted murder charges of cops and $5.2 million bail – live updates". The Independent. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Suspect In Chelsea, Seaside Park Explosions Ordered Held; Investigators Say 'No Indication' Of Broader Cell". CBS Local. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b "Criminal Complaint". United States v. Ahmad Khan Rahami. United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Criminal Complaint". United States v. Ahmad Khan Rahami. United States District Court for the District of New Jersey. September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shoichet, Catherine E. (September 19, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami: What we know about the bombing suspect". CNN. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Ross, Brian; Schwartz, Rhonda; Levine, Mike; Wash, Stephanie; Hayden, Michael Edison; Gallagher, JJ; Shapiro, Emily (September 19, 2016). "Details Emerge About NYC Bomb Suspect Ahmad Khan Rahami". ABC News. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Kleinfield, N. R. (September 19, 2016). "Ahmad Rahami: Fixture in Family's Business and, Lately, a 'Completely Different Person'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Arkin, William; Johnson, Alex; Siemaszko, Corky; Connor, Tracy; Bailey, Chelsea; Bratu, Becky (September 19, 2016). "Ahmad Rahami: What We Know About N.Y., N.J. Bombings Suspect". NBC News. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c Dickson, Caitlin (September 19, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami high school classmate recalls bomb suspect as 'funny'; calls allegations 'shocking'". Yahoo! News. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Sandoval, Edgar; Silverstein, Jason (September 19, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami's family claimed anti-Muslim harassment over their fast food restaurant". The New York Daily News. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Stirling, Stephen (September 19, 2016). "Bombing suspect Ahmad Khan Rahami's family sued Elizabeth for anti-Muslim harassment". NJ.com. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Ingram, David; Ax, Joseph (September 19, 2016). "New York bomb suspect's family clashed with New Jersey city over restaurant". Yahoo! News. Reuters. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Merle, Renae; Zapotosky, Matt; Wang, Amy B.; Berman, Mark; Nakashima, Ellen (September 19, 2016). "Suspect in N.Y., N.J. bombings arrested after shootout; FBI says 'no indication' of terror cell". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Haydon, Tom (September 28, 2016). "Details emerge of Ahmad Khan Rahami's alleged history of violence toward family". NJ.com. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c Siddique, Haroon; Pengelly, Martin; Yuhas, Alan (September 20, 2016). "New York bombings: Ahmad Khan Rahami charged with attempted murder – as it happened". The Guardian. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Boone, Jon (September 23, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami spent time at Pakistan seminary tied to Taliban". The Guardian. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew (September 20, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami: Bombing suspect's 'personality changed after visits to Pakistan and Afghanistan'". The Independent. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Remo, Jessica (September 22, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami's wife is back in U.S. for questioning". NJ.com. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ^ Perez, Evan; Prokupecz, Shimon (September 22, 2016). "Investigators: Ahmad Rahami went to family home after Chelsea bombing". CNN. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Shoichet, Catherine E.; Prokupecz, Shimon; Perez, Evan (September 20, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami's wife left US before bombings". CNN. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Nakashima, Ellen; Berman, Mark; Wan, William (September 21, 2016). "Ahmad Rahami, suspected New York bomber, cited al-Qaeda and ISIS, officials say". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Willingham, AJ (September 19, 2016). "The amazingly quick capture of Ahmad Rahami". CNN. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Goodman, J. David; Gelles, David (September 19, 2016). "Cellphone Alerts Used in New York to Search for Bombing Suspect". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ "New York bombing suspect named as Ahmad Khan Rahami". BBC News. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Richmond, Kait (September 20, 2016). "Sikh man who found bombing suspect: 'I did what every American would have done'". CNN. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "'We caught a terrorist' says proud new Linden chief". nj.com. September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ McCarthy, Craig (September 23, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami shot at least 7 times in Linden arrest, authorities say". nj.com. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ "New York bombing: Investigators seek 2 witnesses". CNN. September 21, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ^ Connor, Tracy (September 20, 2016). "Bomb suspect Ahmad Rahami's ex-girlfriend awarded custody of their child". NBC News. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Pillets, Jeff (September 21, 2016). "Edison woman awarded custody of child with accused bomber". NorthJersey.com. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Ford, Matt; Calamur, Krishnadev; Koren, Marina; Vasilogambros, Matt (September 19, 2016). "What We Know: The Explosions in New York and New Jersey". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Ford, James (September 20, 2016). "Why the $5.2M bail set for Ahmad Khan Rahami doesn't mean he'll walk". pix11.com. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Zauderer, Alyssa; Choudhury, Narmeen (September 20, 2016). "Federal charges filed against Chelsea, NJ bombing suspect Ahmad Khan Rahami". PIX11. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ Weiser, Benjamin; Rosenberg, Eli (September 27, 2016). "Ahmad Khan Rahami's Father and Wife Retain A.C.L.U. to Defend Him". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "The Latest: Injured New Jersey Policeman to Visit School". ABC News. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

External links

Media related to 2016 Manhattan explosion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 2016 Manhattan explosion at Wikimedia Commons

- 2016 crimes in the United States

- 2016 in New Jersey

- 2016 in New York City

- 21st century in Manhattan

- Attacks in the United States in 2016

- Chelsea, Manhattan

- Crimes in New Jersey

- Crimes in New York City

- Elizabeth, New Jersey

- Improvised explosive device bombings in the United States

- Linden, New Jersey

- Seaside Park, New Jersey

- September 2016 crimes

- September 2016 events in the United States

- Terrorist incidents in New Jersey

- Terrorist incidents in New York City

- Terrorist incidents in the United States in 2016