Chinese calligraphy: Difference between revisions

Choixong di (talk | contribs) Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Fixed grammar Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

=== Regular script === |

=== Regular script === |

||

{{Main|Regular script}}'''[[Regular script]]''' ([[Traditional Chinese characters|traditional Chinese]]: 楷書; [[Simplified Chinese characters|simplified Chinese]]: 楷书; [[pinyin]]: ''kǎishū; Hong Kong and Taiwan still use traditional Chinese characters in writing, while mainland China uses simplified Chinese characters as the official script.'' ) is the newest of the Chinese script styles. The regular script first came into existence between the [[Han dynasty|Han]] and [[Cao Wei|Wei]] dynasties, even though it |

{{Main|Regular script}}'''[[Regular script]]''' ([[Traditional Chinese characters|traditional Chinese]]: 楷書; [[Simplified Chinese characters|simplified Chinese]]: 楷书; [[pinyin]]: ''kǎishū; Hong Kong and Taiwan still use traditional Chinese characters in writing, while mainland China uses simplified Chinese characters as the official script.'' ) is the newest of the Chinese script styles. The regular script first came into existence between the [[Han dynasty|Han]] and [[Cao Wei|Wei]] dynasties, even though it was not then popular. The [[regular script]] became mature stylistically around the 7th century.<ref name=":3">{{Cite book|title=Chinese writing|last1=Xigui|first1=Qiu|last2=裘錫圭.|others=Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012, Qiu, Xigui, 裘錫圭|year=2000|isbn=978-1557290717|location=Berkeley, California|pages=143|oclc=43936866}}</ref> The first master of regular script is [[Zhong You]]. Zhong You first used regular script to write some very serious pieces such as memorials to the emperor.<ref name=":3" /> |

||

=== Semi-cursive script === |

=== Semi-cursive script === |

||

Revision as of 22:44, 31 December 2021

| Chinese calligraphy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 書法 法書 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 书法 法书 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Thư pháp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 書法 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 書藝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 書道 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | しょどう (modern) しよだう (historical) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

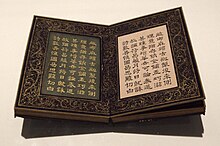

Chinese calligraphy is the writing of Chinese characters as an art form, combining purely visual art and interpretation of the literary meaning. This type of expression has been widely practiced in China and has been generally held in high esteem across East Asia. Calligraphy is considered one of the four most-sought skills and hobbies of ancient Chinese literati, along with playing stringed musical instruments, the board game "Go", and painting. There are some general standardizations of the various styles of calligraphy in this tradition. Chinese calligraphy and ink and wash painting are closely related: they are accomplished using similar tools and techniques, and have a long history of shared artistry. Distinguishing features of Chinese painting and calligraphy include an emphasis on motion charged with dynamic life. According to Stanley-Baker, "Calligraphy is sheer life experienced through energy in motion that is registered as traces on silk or paper, with time and rhythm in shifting space its main ingredients."[1] Calligraphy has also led to the development of many forms of art in China, including seal carving, ornate paperweights, and inkstones.

Characteristics

In China, calligraphy is referred to as shūfǎ or fǎshū (書法/书法, 法書/法书), literally 'way/method/law of writing';[2] shodō (書道) in Japan ('way/principle of writing'); and seoye (서예; 書藝) in Korea ('skill/criterion of writing'[3]);thư pháp (書法) in Vietnam ('handwriting art').

Chinese calligraphy appreciated more or only for its aesthetic quality has a long tradition, and is today regarded as one of the arts (Chinese 藝術/艺术 pinyin: yìshù, a relatively recent word in Chinese)[4] in the countries where it is practised. Chinese calligraphy focuses not only on methods of writing but also on cultivating one's character (人品)[5] and taught as a pursuit (-書法; pinyin: shūfǎ, rules of writing Han characters[6]).

Chinese calligraphy used to be popular in China, Taiwan, Japan , Korea , Vietnam and Hongkong. In Taiwan, students were requested to write Chinese calligraphy starting from primary school all the way to junior high school on weekly basis at least to year 1980. As young generations are "typing" more often than "writing", when PC, tablets and mobile phones became the major communication channels, Chinese calligraphy becomes purely art.

Chinese script styles

Oracle bone script

Oracle bone script was an early form of Chinese characters written on animals' bones. Written on oracle bones – animal bones or turtle plastrons – it is the earliest known form of Chinese writing. The bones were believed to have prophecies written on them. The first appearance of what we recognize unequivocally to refer as "oracle bone inscriptions" comes in the form of inscribed ox scapulae and turtle plastrons from sites near modern Anyang (安阳) on the northern border of Henan province. The vast majority were found at the Yinxu site in this region. They record pyromantic divinations of the last nine kings of the Shang dynasty, beginning with Wu Ding, whose accession is dated by different scholars at 1250 BC or 1200 BC.[7][8] Though there is no proof that the Shang dynasty was solely responsible for the origin of writing in China, neither is there evidence of recognizable Chinese writing from any earlier time or any other place.[9] The late Shang oracle bone writings constitute the earliest significant corpus of Chinese writing and it is also the oldest known member and ancestor of the Chinese family of scripts, preceding the Chinese bronze inscriptions.[10]

Chinese Bronze Inscriptions

Chinese bronze inscriptions were usually written on the Chinese ritual bronzes. These Chinese ritual bronzes include Ding (鼎), Dui (敦), Gu (觚), Guang (觥), Gui (簋), Hu (壺), Jia (斝), Jue (爵), Yi (匜), You (卣), Zun (尊), and Yi (彝).[11] Different time periods used different methods of inscription. Shang bronze inscriptions were nearly all cast at the same time as the implements on which they appear.[12] In later dynasties such as Western Zhou, Spring and Autumn Period, the inscriptions were often engraved after the bronze was cast.[13] Bronze inscriptions are one of the earliest scripts in the Chinese family of scripts, preceded by the oracle bone script.

Seal script

Seal script (Chinese: 篆書; pinyin: zhuànshū) is an ancient style of writing Chinese characters that was common throughout the latter half of the 1st millennium BC. It evolved organically out of the Zhou dynasty script. The Qin variant of seal script eventually became the standard, and was adopted as the formal script for all of China during the Qin dynasty.

Clerical script

The Clerical script (traditional Chinese: 隸書; simplified Chinese: 隶书; pinyin: lìshū) is an archaic style of Chinese calligraphy. The clerical script was first used during the Han dynasty and has lasted up to the present. The clerical script is considered a form of the modern script though it was replaced by the standard script relatively early. This occurred because the graphic forms written in a mature clerical script closely resemble those written in standard script.[12] The clerical script is still used for artistic flavor in a variety of functional applications because of its high legibility for reading.

Regular script

Regular script (traditional Chinese: 楷書; simplified Chinese: 楷书; pinyin: kǎishū; Hong Kong and Taiwan still use traditional Chinese characters in writing, while mainland China uses simplified Chinese characters as the official script. ) is the newest of the Chinese script styles. The regular script first came into existence between the Han and Wei dynasties, even though it was not then popular. The regular script became mature stylistically around the 7th century.[14] The first master of regular script is Zhong You. Zhong You first used regular script to write some very serious pieces such as memorials to the emperor.[14]

Semi-cursive script

Semi-cursive script (simplified Chinese: 行书; traditional Chinese: 行書; pinyin: Xíngshū), is a cursive style of Chinese characters. Because it is not as abbreviated as cursive, most people who can read regular script can read semi-cursive. It is highly useful and also artistic.

Cursive script (East Asia)

Cursive script (simplified Chinese: 草书; traditional Chinese: 草書; pinyin: cǎoshū) originated in China during the Han dynasty through the Jin period (link needed). The cursive script is faster to write than other styles, but difficult to read for those unfamiliar with it. The "grass" in Chinese was also used in the sense of "coarse, rough; simple and crude."[15] It would appear that cǎo in the term caoshu "grass script" was used in this same sense. The term cǎoshū has broad and narrow meanings. In the broad sense, it is non-temporal and can refer to any characters which have been hastily written. In the narrow sense, it refers to the specific handwriting style in Han dynasty.[16]

History

Ancient China

Chinese characters can be retraced to 4000 B.C. signs (Lu & Aiken 2004).

In 2003, at the site of Xiaoshuangqiao, about 20 km southeast of the ancient Zhengzhou Shang City, ceramic inscriptions dating to 1435–1412 B.C. have been found by archaeologists. These writings are made in cinnabar paint. Thus, the dates of writing in China have been confirmed for the Middle Shang period.[17]

The ceramic ritual vessel vats that bear these cinnabar inscriptions were all unearthed within the palace area of this site. They were unearthed mostly in the sacrificial pits holding cow skulls and cow horns, but also in other architectural areas. The inscriptions are written on the exterior and interior of the rim, and the exterior of the belly of the large type of vats. The characters are mostly written singly; character compounds or sentences are rarely seen.[17]

The contemporary Chinese character's set principles were clearly visible in ancient China's Jiǎgǔwén characters(甲骨文) carved on ox scapulas and tortoise plastrons around 14th - 11th century BCE (Lu & Aiken 2004). Brush-written examples decay over time and have not survived. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved (Keightley, 1978). Each archaic kingdom of current China continued to revise its set of characters.

Imperial China

For more than 2,000 years, China's literati—Confucian scholars and literary men who also served the government as officials—have been connoisseurs and practitioners of this art.[18] In Imperial China, the graphs on old steles — some dating from 200 BC, and in Xiǎozhuàn style (small seal script) — are still accessible.

Scribes in China and Mongolia practiced the art of calligraphy to copying Buddhist texts. Since these text were so venerated, the act of copying them down (and the beautiful calligraphy employed, was supposed to have a purifying effect on the soul. "The Act of copying them [Buddihist texts] could bring a scribe closer to perfection and earn him merit."[19]

In about 220 BC, the emperor Qin Shi Huang(秦始皇, 259–210 BC), the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them Li Si's (李斯, 246 BC - 208 BC) character unification, which created a set of 3300 standardized Xiǎozhuàn characters.[20] Despite the fact that the main writing implement of the time was already the brush, little paper survives from this period, and the main examples of this style are on steles.

The Lìshū style (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, were also authorised under Qin Shi Huang.[21][self-published source?] While it is a common mistake to believe that Lishu was created by Cheng Miao alone during Qing Shi Huang's regime, Lishu was developed from pre-Qin era to the Han dynasty (202 BC-220 AD).

During the fourth century AD, calligraphy came to full maturity.[18] The Kǎishū style (traditional regular script) — still in use today — and attributed to Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303 CE-361 AD) and his followers, is even more regularized.[21] reached its peak in the Tang Dynasty, when famous calligraphers like Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan produced most of the fine works in Kaishu. Its spread was encouraged by Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang (926 CE -933 AD), who ordered the printing of the classics using new wooden blocks in Kaishu. Printing technologies here allowed shapes to stabilize. The Kaishu shape of characters 1000 years ago was mostly similar to that at the end of Imperial China.[21] But small changes have been made, for example in the shape of 广 which is not absolutely the same in the Kangxi Dictionary of 1716 as in modern books. The Kangxi and current shapes have tiny differences, while stroke order is still the same, according to old style.[22]

Cursive styles such as Xíngshū (semi-cursive or running script) and Cǎoshū (cursive or sloppy script) are less constrained and faster, where more movements made by the writing implement are visible. These styles' stroke orders vary more, sometimes creating radically different forms. They are descended from Clerical script, at the same time as Regular script (Han Dynasty 202 BC-220 AD), but Xíngshū and Cǎoshū were used for personal notes only and were never used as a standard. Caoshu style was highly appreciated during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (140 BC−87 BC).[21]

Styles which did not survive include Bāfēnshū, a mix of 80% Xiaozhuan style and 20% Lishu.[21] Some Variant Chinese characters were unorthodox or locally used for centuries. They were generally understood but always rejected in official texts. Some of these unorthodox variants, in addition to some newly created characters, were incorporated in the Simplified Chinese character set.

Hard-pen calligraphy

This way of writing started to develop in the 1900s when fountain pens were imported into China from the west. Writing with fountain pens remained a convenience until the 1980s. With the Reform and Open, public focused on practicing hard-pen calligraphy. People usually use Chinese simplified characters in semi-cursive or regular style.[12]

Printed and computer styles

Examples of modern printed styles are Song from the Song Dynasty's printing press, and sans-serif. These are not considered traditional styles, and are normally not written.

Gallery along history

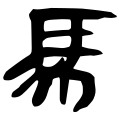

Different scripts of 馬 / 马 (horse) along history:

-

Regular script (traditional)

-

Regular script (simplified)

Materials and tools

The ink brush, ink, paper, and inkstone are essential implements of Chinese calligraphy. They are known together as the Four Treasures of the Study. In addition to these four tools, a water-dropper, desk pads and paperweights are also used by calligraphers.

Brush

A brush is the traditional writing instrument for Chinese calligraphy. The body of the brush is commonly made from bamboo or other materials such as wood, porcelain, or horn. The head of the brush is typically made from animal hair, such as weasel, rabbit, deer, goat, pig, tiger, wolf, etc. There is also a tradition in both China and Japan of making a brush using the hair of a newborn child, as a once-in-a-lifetime souvenir. This practice is associated with the legend of an ancient Chinese scholar who scored first in the imperial examinations by using such a personalized brush.[citation needed] Calligraphy brushes are widely considered an extension of the calligrapher's arm.

Today, calligraphy may also be done using a pen.

Paper

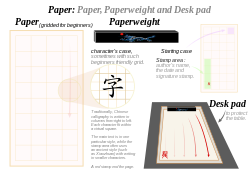

Paper is frequently sold together with a paperweight and desk pad.

Some people insist that Chinese calligraphy should use special papers, such as Xuan paper, Maobian paper, Lianshi paper etc. Any modern papers can be used for brush writing. Because of the long-term uses, Xuan paper became well known by most of Chinese calligraphers.

In China, Xuanzhi (宣紙), traditionally made in Anhui province, is the preferred type of paper. It is made from the Tatar wingceltis (Pteroceltis tatarianovii), as well as other materials including rice, the paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), bamboo, hemp, etc. In Japan, washi is made from the kozo (paper mulberry), ganpi (Wikstroemia sikokiana), and mitsumata (Edgeworthia papyrifera), as well as other materials such as bamboo, rice, and wheat.

Paperweights

Paperweights are used to hold down paper. A paperweight is often placed at the top of all but the largest pages to prevent slipping; for smaller pieces the left hand is also placed at the bottom of the page for support. Paperweights come in several types: some are oblong wooden blocks carved with calligraphic or pictorial designs; others are essentially small sculptures of people or animals. Like ink stones, paperweights are collectible works of art on their own right.

Desk pads

The desk pad (Chinese T: 畫氈, S: 画毡, Pinyin: huàzhān; Japanese: 下敷 shitajiki) is a pad made of felt. Some are printed with grids on both sides, so that when it is placed under the translucent paper, it can be used as a guide to ensure correct placement and size of characters. However, these printed pads are used only by students. Both desk pads and the printed grids come in a variety of sizes.

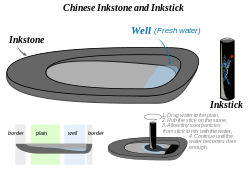

Ink and inkstick

Ink is made from lampblack (soot) and binders, and comes in inksticks which must be rubbed with water on an inkstone until the right consistency is achieved. Much cheaper, pre-mixed bottled inks are now available, but these are used primarily for practice as stick inks are considered higher quality and chemical inks are more prone to bleeding over time, making them less suitable for use in hanging scrolls. Learning to rub the ink is an essential part of calligraphy study. Traditionally, Chinese calligraphy is written only in black ink, but modern calligraphers sometimes use other colors. Calligraphy teachers use a bright orange or red ink with which they write practice characters on which students trace, or to correct students' work.

Inkstone

Commonly made from stone, ceramic, or clay, an inkstone is used to grind the solid inkstick into liquid ink and to contain the ink once it is liquid. Chinese inkstones are highly prized as art objects and an extensive bibliography is dedicated to their history and appreciation, especially in China.

Seal and seal paste

Calligraphic works are usually completed by the calligrapher applying one or more seals in red ink. The seal can serve the function of a signature.

Technique

The shape, size, stretch, and type of hair in the brush, the color and density of the ink, as well as the absorptive speed and surface texture of the paper are the main physical parameters influencing the final result. The calligrapher also influences the result by the quantity of ink/water he lets the brush take up, then by the pressure, inclination, and direction he gives to the brush, producing thinner or bolder strokes, and smooth or toothed borders. Eventually, the speed, acceleration and deceleration of the writer's moves and turns, and the stroke order give "spirit" to the characters by influencing greatly their final shape. The "spirit" is referred to yi in Chinese calligraphy. Yi means "intention or idea" in Chinese. The more practice a calligrapher has, his or her technique will transfer from youyi (intentionally making a piece of work) to wuyi (creating art with unintentional moves). Wuyi is considered a higher stage for calligraphers, which require the calligrapher to have perfect control over the brush and wrist and following his or her heart.[24]

Study

Traditionally, the bulk of the study of calligraphy is composed of copying strictly exemplary works from the apprentice's master or from reputed calligraphers, thus learning them by rote. The master showing the 'right way' to draw items, which the apprentice have to copy strictly, continuously, until the move becomes instinctive and the copy perfect. Deviation from the model is seen as a failure.[1] Competency in a particular style often requires many years of practice. Correct strokes, stroke order, character structure, balance, and rhythm are essential in calligraphy. A student would also develop their skills in traditional Chinese arts, as familiarity and ability in the arts contributes to their calligraphy.

Since the development of regular script, nearly all calligraphers have started their study by imitating exemplary models of regular script. A beginning student may practice writing the character 永 (Chinese: yǒng, eternal) for its abundance of different kinds of strokes and difficulty in construction. The Eight Principles of Yong refers to the eight different strokes in the character, which some argue summarizes the different strokes in regular script.

How the brush is held depends on the calligrapher and which calligraphic genre is practiced. Commonly, the brush is held vertically straight gripped between the thumb and middle finger. The index finger lightly touches the upper part of the shaft of the brush (stabilizing it) while the ring and little fingers tuck under the bottom of the shaft, leaving a space inside the palm. Alternatively, the brush is held in the right hand between the thumb and the index finger, very much like a Western pen. A calligrapher may change his or her grip depending on the style and script. For example, a calligrapher may grip higher for cursive and lower for regular script.

In Japan, smaller pieces of Japanese calligraphy are traditionally written while in seiza. In modern times, however, writers frequently practice calligraphy seated on a chair at a table. Larger pieces may be written while standing; in this case the paper is usually placed directly on the floor, but some calligraphers use an easel.

Basic calligraphy instruction is part of the regular school curriculum in both China and Japan and specialized programs of study exist at the higher education level in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. In contemporary times, debate emerged on the limits of this copyist tradition within the modern art scenes, where innovation is the rule, while changing lifestyles, tools, and colors are also influencing new waves of masters.[1][25]

Chinese calligraphy is being promoted in Chinese schools to counter Character amnesia brought on by technology usage.[26]

In recent study, Chinese calligraphy writing have been used as cognitive intervention strategy among older adults or people with mild cognitive impairment. For example, in a recent randomized control trial experiment, calligraphy writing enhanced both working memory and attention control compared to controlled groups.[27]

In contemporary China, a small but significant number of practitioners have made calligraphy their profession, and provincial and national professional societies exist, membership in which conferring considerable prestige.[28] By tradition, the price of a particular artist's work is priced in terms of the length of paper on which it is written. Works by well-regarded contemporary calligraphers may fetch thousands to tens of thousands of yuan (renminbi) per chi (a unit of length, roughly equal to a foot) of artwork. As with other artwork, the economic value of calligraphy has increased in recent years as the newly-rich in China search for safe investments for their wealth.[29]

Rules of Modern Calligraphy

While appreciating calligraphy will depend on individual preferences, there are established traditional rules and those who repeatedly violate them are not considered legitimate calligraphers.[4] The famous modern Chinese calligrapher Tian Yunzhang, member of the Chinese Calligrapher Association, summarized rules of modern calligraphy. The following citation are from the video collection Mei ri yi ti mei ri yi zi (每日一题,每日一字) [zh] regarded as great reference for calligraphy learners, in which Tian made deep analysis of different characters. Among these rules are:

- The characters must be written correctly.[4] A correctly written character is composed in a way that is accepted as correct by legitimate calligraphers. Calligraphic works often use variant Chinese characters, which are deemed correct or incorrect case-by-case, but in general, more popular variants are more likely to be correct. Correct characters are written in the traditional stroke order and not a modern standard.

- The characters must be legible.[4] As calligraphy is the method of writing well, a calligraphic work must be recognizable as script, and furthermore be easily legible to those familiar with the script style, although it may be illegible to those unfamiliar with the script style. For example, many people cannot read cursive, but a calligraphic work in cursive can still be considered good if those familiar with cursive can read it.

- The characters must be concise.[4] This is in contrast to Western calligraphy where flourishes are acceptable and often desirable. Good Chinese calligraphy must be unadorned script. It must also be in black ink unless there is a reason to write in other ink.

- The characters must fit their context.[4] All reputable calligraphers in China were well educated and well read. In addition to calligraphy, they were skilled in other areas, most likely painting, poetry, music, opera, martial arts, and Go. Therefore, their abundant education contributed to their calligraphy. A calligrapher practicing another calligrapher's characters would always know what the text means, when it was created, and in what circumstances. When they write, their characters' shape and weight agrees with the rhythm of the phrases, especially in less constrained styles such as semi-cursive and cursive. One who does not know the meaning of the characters they write, but varies their shape and weight on a whim, does not produce good calligraphy.

- The characters must be aesthetically pleasing.[4] Generally, characters that are written correctly, legibly, concisely, and in the correct context are also aesthetically pleasing to some degree. Characters that violate the above rules are often less aesthetically pleasing. An experienced calligrapher will consider the quality of the line, the structure of each character which the lines are placed, the compositional organization of groups of characters. Throughout the work, the brush line of light or dark, dry or wet should record the process of the artist creating the work vividly.[30]

Influences

Calligraphy in Japan, Korea and Vietnam

The Japanese and Koreans have developed their own specific sensibilities and styles of calligraphy while incorporating Chinese influences, as well as applying to specific scripts. Japanese calligraphy extends beyond Han characters to also include local scripts such as hiragana and katakana.

In the case of Korean calligraphy, the Hangeul and the existence of the circle required the creation of a new technique.[31]

Vietnamese calligraphy is heavily influenced by Chinese calligraphy. Currently, in Vietnam, calligraphy is used for two types of characters: Hán Nôm and chữ Quốc ngữ.

Other arts

The existence of temporary calligraphy, or water calligraphy, is also to be noted. This is the practice of water-only calligraphy on the floor which dries out within minutes. This practice is especially appreciated by the new generation of retired Chinese in public parks of China.

Calligraphy has influenced ink and wash painting, which is accomplished using similar tools and techniques. Calligraphy has influenced most major art styles in East Asia, including Ink and wash painting, a style of Chinese, Japanese, Korean painting and Vietnamese based entirely on calligraphy.

Notable Chinese calligraphers

Qin Dynasty

- Li Si 李斯 (280–208BC)

Han Dynasty

Jin Dynasty

- Wei Shuo 衞鑠 (272–349)

- Lu Ji 陸機 (261–303)

- Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (303–361)

- Wang Xianzhi 王獻之 (344–386)

- Wang Xun 王珣 (349–400)

Sui Dynasty

- Zhiyong 智永 (ca. 6th century)

- Ding Daohu 丁道護 (ca. 6th century)

Tang Dynasty

- Ouyang Xun 歐陽詢 (557–641)

- Yu Shinan 虞世南 (558–638)

- Chu Suiliang 褚遂良 (597–658)

- Huairen 懷仁 (ca. 7th century)

- Emperor Taizong of Tang 唐太宗 李世民 (599–649)

- Li Yangbing 李陽冰 (721/2–785)

- Zhang Xu 張旭 (658–747)

- Yan Zhenqing 顏眞卿 (709–785)

- Huaisu 懷素 (737–799)

- Liu Gongquan 柳公權 (778–865)

- Du Mu 杜牧 (803–852)

Five Dynasties

- Yang Ningshi 楊凝式 (873–954)

Song Dynasty

- Cai Xiang 蔡襄 (1012–1067)

- Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037–1101)

- Huang Tingjian 黃庭堅 (1045–1105)

- Mi Fu 米黻 (1051–1107)

- Emperor Huizong of Song 宋徽宗 趙佶 (1082–1135)

- Emperor Gaozong of Song 宋高宗 趙構 (1107–1187)

- Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130-1200)

Yuan Dynasty

- Zhao Mengfu 趙孟頫 (1254–1322)

- Ni Zan 倪瓚 (1301–1374)

Ming Dynasty

- Tang Yin 唐寅 (1470–1524)

- Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470–1559)

- Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636)

- Huang Ruheng 黃汝亨 (1558–1626)

- Wang Duo 王鐸 (1592–1652)

Qing Dynasty

- Zhu Da 朱耷 (1626–1705)

- Zheng Xie 鄭燮 (1693–1765)

- Yang Shoujing 楊守敬 (1839–1915)

Modern Times

- Wu Changshuo 吳昌碩 (1844–1927)

- Kang Youwei 康有為 (1858–1927)

- Hong Yi 弘一法師 (1880–1942)

Gallery

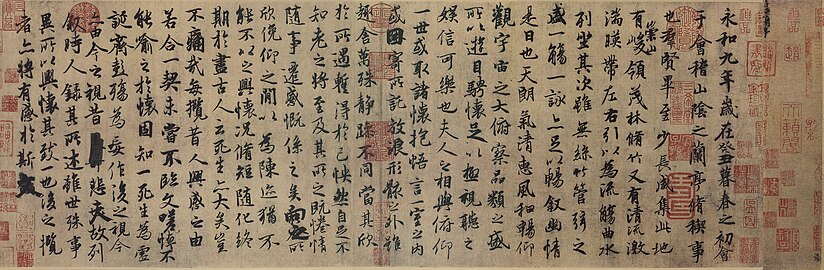

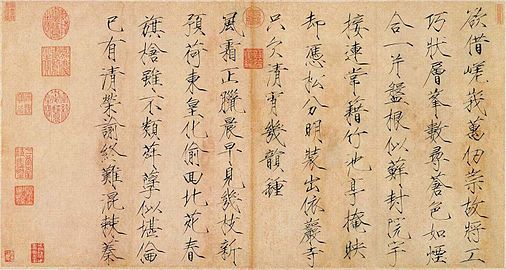

-

A copy of Wang Xizhi's Lantingji Xu, the most famous Chinese calligraphic work.

-

Part of a stone rubbing of 黄庭经 by Wang Xizhi

-

A copy of 上虞帖 by Wang Xizhi

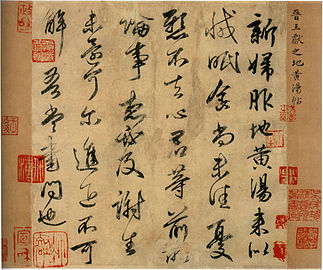

-

A Tang Dynasty copy of 新婦地黃湯帖 by Wang Xianzhi

-

Part of a stone rubbing of 九成宮醴泉銘 by Ouyang Xun

-

Part of a stone rubbing of 雁塔聖教序 by Chu Suiliang

-

Part of a stone rubbing of 顏勤禮碑 by Yan Zhenqing

-

Cry for noble Saichō by Emperor Saga

-

A work by Emperor Huizong of Song

-

Buiseonrando by Kim Jeonghui

See also

- Calligraphy

- Chinese art

- Chinese characters

- East Asian script styles

- Eight Principles of Yong

- Ink and wash painting

- Japanese art

- Korean art

- Songti

- Vietnamese art

- Three perfections - integration of calligraphy, poetry and painting

- Wonton font

References

- ^ a b c (Stanley-Baker 2010a)

- ^ 書 being here used as in 楷书/楷書, etc., and meaning 'writing style'.

- ^ Wang Li; et al. (2000). 王力古漢語字典. Beijing: 中華書局. p. 1118. ISBN 978-7101012194.

- ^ a b c d e f g 田蘊章《每日一題每日一字》 - Internet video series on Chinese calligraphy

- ^ "Shodo and Calligraphy". Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Shu Xincheng 舒新城, ed. Cihai (辭海 'Sea of Words'). 3 vols. Shanghai: Zhonghua. 1936.

- ^ Xueqin, Li (2002-06-01). "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Methodology and Results". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4 (1): 321–333. doi:10.1163/156852302322454585. ISSN 1387-6813.

- ^ N., Keightley, David (2000). The ancestral landscape : time, space, and community in late Shang China, ca. 1200-1045 B.C. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley. p. 228. ISBN 978-1557290700. OCLC 43641424.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The world's writing systems. Daniels, Peter T., Bright, William, 1928-2006. New York: Oxford University Press. 1996. ISBN 978-0195079937. OCLC 31969720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Xigui, Qiu; 裘錫圭. (2000). Chinese writing. Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012, Qiu, Xigui, 裘錫圭. Berkeley, California. p. 80. ISBN 978-1557290717. OCLC 43936866.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hui., Wang; 王輝. (2006). Shang Zhou Jin wen (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wen wu chu ban she. ISBN 978-7501014866. OCLC 66438456.

- ^ a b c Xigui, Qiu; 裘錫圭. (2000). Chinese writing. Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012, Qiu, Xigui, 裘錫圭. Berkeley, California. p. 113. ISBN 978-1557290717. OCLC 43936866.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Xigui, Qiu; 裘錫圭. (2000). Chinese writing. Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012, Qiu, Xigui, 裘錫圭. Berkeley, California. p. 73. ISBN 978-1557290717. OCLC 43936866.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Xigui, Qiu; 裘錫圭. (2000). Chinese writing. Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012, Qiu, Xigui, 裘錫圭. Berkeley, California. p. 143. ISBN 978-1557290717. OCLC 43936866.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Xigui, Qiu; 裘錫圭. (2000). Chinese writing. Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012, Qiu, Xigui, 裘錫圭. Berkeley, California. p. 130. ISBN 978-1557290717. OCLC 43936866.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Xigui, Qiu; 裘錫圭. (2000). Chinese writing. Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012, Qiu, Xigui, 裘錫圭. Berkeley, California. p. 131. ISBN 978-1557290717. OCLC 43936866.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Song Guoding (2004), The Cinnabar Inscriptions Discovered at the Xiaoshuangqiao Site, Zhengzhou. Chinese Archaeology. Volume 4, Issue 1, Pages 98–102

- ^ a b STOKSTAD, MARILYN; W. COTHREN, MICHAEL (2017). ART HISTORY Volume I. The United States of America; New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-205-87347-0.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles, USA. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-60606-083-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fazzioli, Edoardo (1987) [1987]. Chinese calligraphy : from pictograph to ideogram : the history of 214 essential Chinese/Japanese characters. calligraphy by Rebecca Hon Ko. New York: Abbeville Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-89659-774-7.

And so the first Chinese dictionary was born, the Sān Chāng, containing 3,300 characters

- ^ a b c d e Blakney, p6 : R. B. Blakney (2007). A Course in the Analysis of Chinese Characters. Lulu.com. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-897367-11-7.[self-published source]

- ^ 康熙字典 Kangxi Zidian, 1716. Scanned version available at www.kangxizidian.com. See for example the radicals 卩, 厂 or 广, p.41. The 2007 common shape for those characters does not clearly show the stroke order, but old versions, visible on the Kangxi Zidian p.41 clearly allow the stroke order to be determined.

- ^ "Chinese - Brushwasher in the Form of a Leaf". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Shi, Xiongbo (2018). "The Aesthetic Concept of Yi 意 in Chinese Calligraphic Creation". Philosophy East and West. 68 (3): 871–886. doi:10.1353/pew.2018.0076.

- ^ (Stanley-Baker 2010b, pp. 9–10)

- ^ "New calligraphy classes for China's internet generation". BBC NEWS ASIA-PACIFIC. 27 August 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ Chan, SCC (2017). "Chinese Calligraphy Writing for Augmenting Attentional Control and Working Memory of Older Adults at Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 58 (3): 735–746. doi:10.3233/JAD-170024. PMID 28482639.

- ^ For example, the China Calligraphers Association (中国书法家协会, [1]) is a national organization.

- ^ "The art market in 2017".

- ^ Barnhart, Richard (1972). "Chinese Calligraphy: The Inner World of the Brush". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 30 (5): 230–241. doi:10.2307/3258680. JSTOR 3258680.

- ^ Daikynguyen.com Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Li, Wendan (2009). Chinese writing and calligraphy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-8248-3364-0.

- Burckhardt, O. "The Rhythm of the Brush" Archived 2013-12-26 at the Wayback Machine Quadrant, Vol 53, No 6, (June 2009) pp. 124–126. A review-essay that explores the motion of the brush as the hallmark of Chinese calligraphy.

- Daniels O, Dictionary of Japanese (Sōsho) Writing Forms, Lunde Humphries, 1944 (reprinted 1947)

- Deng Sanmu 鄧散木, Shufa Xuexi Bidu 書法學習必讀. Hong Kong Taiping Book Department Publishing 香港太平書局出版: Hong Kong, 1978.

- Emmanuelle Lesbre, Jianlong Liu: La Peinture Chinoise. Hazan, Paris, 2005, ISBN 978-2-850-25922-7.

- Kwo, Da-Wei (David) (1981) [1990]. Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History Aesthetics and Techniques. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26481-5

- Liu, Shi-yee (2007). Straddling East and West: Lin Yutang, a modern literatus: the Lin Yutang family collection of Chinese painting and calligraphy. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588392701.

- Lu, W; Aiken, M (2004), "Origins and evolution of Chinese writing systems and preliminary counting relationships", Accounting History, vol. 9, pp. 25–51, doi:10.1177/103237320400900303, S2CID 153528030

- Ouyang, Zhongshi & Fong, Wen C., Eds, Chinese Calligraphy, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2008. ISBN 9780300121070

- Qiu Xigui, Chinese Writing, Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley, 2000. ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

- Stanley-Baker, Joan (May 2010a), Ink Painting Today (PDF), vol. 10, Centered on Taipei, pp. 8–11, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-17

- Stanley-Baker, Joan (June 2010b), Ink Painting Today (PDF), vol. 10, Centered on Taipei, pp. 18–21, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-21

Further reading

- Tsui, Chung-hui 崔中慧 (2020) Chinese Calligraphy and Early Buddhist Manuscripts. Oxford: Indica et Buddhica. ISBN 978-0-473-54012-8 (Open access PDF).

External links

- Chinese Calligraphy - Dao of Calligraphy in English & Mandarin Chinese

- Chinese Calligraphy at China Online Museum

- Chinese calligraphy

- Styles of Chinese calligraphy

- Models of Chinese calligraphy - Generator of Chinese calligraphy model

- History of Chinese Calligraphy

- Basic Calligraphy Styles From Taoism contains introductory comparisons of different calligraphy styles of basic characters.

- The History of Chinese Calligraphy at BeyondCalligraphy.com

- Introduction of Chinese Ground Calligraphy or Dishu - mildchina

- 名家书法 (Masters of Calligraphy). Enter a character, click, and see range of variations for that character by different calligraphic masters.