Gotse Delchev: Difference between revisions

m Rv not an improvement - NPOV, WP:NOTEVERYTHING, WP:NOTNEWS, WP:RELEVANCE. |

→During the Cold war: Trimmed information irrelevant for this subject, c/e, tagged unsourced and potentially irrelevant content. |

||

| Line 276: | Line 276: | ||

=== During the Cold war === |

=== During the Cold war === |

||

{{undue weight section|date=August 2020}} |

{{undue weight section|date=August 2020}} |

||

In 1934 [[Resolution of the Comintern on the Macedonian Question|the Comintern gave its support]] to the idea that the [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonian]] [[Slavs]] constituted a separate [[nation]].<ref name="dawisha&parrott">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bNvbHCUs3tUC&pg=PA229 |title=Politics, power, and the struggle for democracy in South-East Europe, Volume 2 of Authoritarianism and Democratization and authoritarianism in postcommunist societies, Karen Dawisha, Bruce Parrott, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 229–230 |isbn=0521597331 |access-date=20 November 2011|last1=Dawisha |first1=Karen |last2=Parrott |first2=Bruce |date=13 June 1997}}</ref> Prior to the [[Second World War]], this view on the Macedonian issue had been of little practical importance. However, during the war these ideas were supported by the pro-Yugoslav [[People's Liberation Army of Macedonia|Macedonian communist partisans]], who strengthened their positions in 1943, referring to the ideals of Gotse Delchev.{{cn|date=February 2023}} After the [[Red Army]] entered the [[Balkans]] in late 1944, new communist regimes came into power in [[Kingdom of Bulgaria|Bulgaria]] and [[Yugoslavia]]. In this way their policy on the [[Macedonian Question]] was committed to the [[Comintern]] policy of supporting the development of a distinct ethnic Macedonian consciousness.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bNvbHCUs3tUC&pg=PA229 |title=Politics, power, and the struggle for democracy in South-East Europe, Volume 2 of Authoritarianism and Democratization and authoritarianism in postcommunist societies, Karen Dawisha, Bruce Parrott, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 229–230 |isbn=0521597331 |access-date=20 November 2011|last1=Dawisha |first1=Karen |last2=Parrott |first2=Bruce |date=13 June 1997}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/booksid=hafLHZgZtt4C&pg=PA808 |title=Europe since 1945. Encyclopedia |author=Bernard Anthony Cook |isbn=978 0815340584 |page=808 |date=21 April 2009 |access-date=20 November 2011}}</ref> The region of [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonia]] was proclaimed as the connecting link for the establishment of a future [[Balkan Communist Federation]]. The newly established [[Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia|Yugoslav]] [[People's Republic of Macedonia]], was characterized as the natural result of Delchev's aspirations for autonomous Macedonia.<ref name="lampe&mazower">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gE1c4wK-ASAC&pg=PA110 |title=Ideologies and national identities: the case of twentieth-century Southeastern Europe, John R. Lampe, Mark Mazower, Central European University Press, 2004 |pages=112–115 |isbn=9639241822 |access-date=20 November 2011|last1=Lampe |first1=John |last2=Mazower |first2=Mark |date=January 2004}}</ref> |

|||

In 1934 [[Resolution of the Comintern on the Macedonian Question|the Comintern gave its support]] to the idea that the [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonian]] [[Slavs]] constituted a separate [[nation]].<ref>Duncan Perry, "The Republic of Macedonia: finding its way" in Karen Dawisha and Bruce Parrot (eds.), Politics, power and the struggle for Democracy in South-Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 228-229. |

|||

</ref> Prior to the [[Second World War]], this view on the Macedonian issue had been of little practical importance. However, during the War these ideas were supported by the pro-Yugoslav [[People's Liberation Army of Macedonia|Macedonian communist partisans]], who strengthened their positions in 1943, referring to the ideals of Gotse Delchev. After the [[Red Army]] entered the [[Balkans]] in the late 1944, new communist regimes came into power in [[Kingdom of Bulgaria|Bulgaria]] and [[Yugoslavia]]. In this way their policy on the [[Macedonian Question]] was committed to the [[Comintern]] policy of supporting the development of a distinct ethnic Macedonian consciousness.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bNvbHCUs3tUC&pg=PA229 |

|||

|title=Politics, power, and the struggle for democracy in South-East Europe, Volume 2 of Authoritarianism and Democratization and authoritarianism in postcommunist societies, Karen Dawisha, Bruce Parrott, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 229–230 |

|||

|isbn=0521597331 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011|last1=Dawisha |

|||

|first1=Karen |

|||

|last2=Parrott |

|||

|first2=Bruce |

|||

|date=13 June 1997 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hafLHZgZtt4C&pg=PA808 |

|||

|title=Europe since 1945. Encyclopedia |

|||

|author=Bernard Anthony Cook |

|||

|isbn=978-0815340584 |

|||

|page=808 |

|||

|date=21 April 2009 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011}} |

|||

</ref> The region of [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonia]] was proclaimed as the connecting link for the establishment of a future [[Balkan Communist Federation]].<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hafLHZgZtt4C&pg=PA808 |

|||

|title=Europe since 1945. Encyclopedia by Bernard Anthony Cook. pg. 808 |

|||

|isbn=978-0815340584 |

|||

|date=21 April 2009 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011|last1=Cook |

|||

|first1=Bernard A. |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> The newly established [[Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia|Yugoslav]] [[People's Republic of Macedonia]], was characterized as natural result of Delchev's aspirations for autonomous Macedonia.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gE1c4wK-ASAC&pg=PA110 |

|||

|title=Ideologies and national identities: the case of twentieth-century Southeastern Europe, John R. Lampe, Mark Mazower, Central European University Press, 2004, pp. 112–113 |

|||

|isbn=9639241822 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011|last1=Lampe |

|||

|first1=John |

|||

|last2=Mazower |

|||

|first2=Mark |

|||

|date=January 2004 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

However, initially, he was proclaimed by its Communist leader [[Lazar Koliševski]] as: "''...one Bulgarian of no significance for the liberation struggles...''".<ref>Мичев. Д. Македонският въпрос и българо-югославските отношения – 9 септември 1944–1949, Издателство: СУ Св. Кл. Охридски, 1992, стр. 91.</ref> But at the beginning of 1946, a conference of the Macedonian Communists was held, at which [[Vasil Ivanovski]] presented a report entitled "Current Issues in Macedonia". The report claimed that Gotse may have considered himself and the Macedonian Slavs Bulgarians, but he was not clear about the ethnic character of the Macedonians.<ref>Ivanovski, Vasil. Current Issues in Macedonia, Published by the Popular Front of the Yugoslavs in Bulgaria, Sofia, 1946.</ref> As a result on 7 October 1946, under pressure from [[Moscow]],<ref name="liotta">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h_LBmnBl99QC&pg=PA292 |title=Dismembering the state: the death of Yugoslavia and why it matters |author=P. H. Liotta |year=2001 |isbn=0739102125 |page=292 |publisher=Lexington Books |access-date=20 November 2011}}</ref> as part of the policy to foster the development of Macedonian national consciousness, Delchev's remains were transported to [[Skopje]].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZmesOn_HhfEC&pg=PA68 |title=The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world |author=Loring M. Danforth |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=1997 |isbn=0691043566 |page=68 |access-date=20 November 2011}}</ref> On the occasion of sending the remains, the [[regent]] and a member of the [[Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and Arts]], [[Todor Pavlov]] presented a [[s:en:A speech by Todor Pavlov on the departure of Gotse Delchev's remains for Skopje - 1946|speech]] on a solemn assembly held in the [[Ivan Vazov National Theatre|National Theater in Sofia]].<ref>[http://www.promacedonia.org/mm/mm_1946_1_1.htm сп. Македонска мисъл, кн. 1-2, год. 2, 1946, Тодор Павлов, Гоце Делчев.]</ref>{{Relevance inline|date=February 2023}} On 10 October, the bones were enshrined in a marble sarcophagus in the yard of the church [[Church of the Holy Salvation, Skopje|"Sveti Spas"]], where they have remained since.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h_LBmnBl99QC&pg=PA292 |title=Dismembering the state: the death of Yugoslavia and why it matters |author=P. H. Liotta |year=2001 |isbn=0739102125 |page=292 |publisher=Lexington Books |access-date=20 November 2011}}</ref> Delchev's name became part of the anthem of [[SR Macedonia]] - ''[[Denes nad Makedonija|Today over Macedonia]]''.<ref>{{cite book |author=Pål Kolstø |title=Strategies of Symbolic Nation-building in South Eastern Europe |date=2016 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781317049364 |page=187}}</ref> After the [[Tito–Stalin split]] in 1948, the then Macedonian communist elite discussed the idea to scrap the name of Delchev from the anthem of the country, as he was suspected again of being [[Bulgarophile]] element, but this idea was finally abandoned.<ref>Последното интервју на Мише Карев: Колишевски и Страхил Гигов сакале да ги прогласат Гоце, Даме и Никола за Бугари! [https://denesen.mk/poslednoto-intervju-na-mishe-karev-kolishevski-i-strahil-gigov-sakale-da-gi-proglasat-goce-dame-i-nikola-za-bugari/ Денешен весник, 01.07.2019].</ref> |

|||

However, initially he was proclaimed by its Communist leader [[Lazar Koliševski]] as: "''...one Bulgarian of no significance for the liberation struggles...''".<ref>Мичев. Д. Македонският въпрос и българо-югославските отношения – 9 септември 1944–1949, Издателство: СУ Св. Кл. Охридски, 1992, стр. 91. |

|||

</ref> But at the beginning of 1946, a conference of the Macedonian Communists was held, at which [[Vasil Ivanovski]] presented a report entitled "Current Issues in Macedonia". The report claimed that Gotse may have considered himself and the Macedonian Slavs Bulgarians, but he was not clear about the ethnic character of the Macedonians.<ref>Ivanovski, Vasil. Current Issues in Macedonia, Published by the Popular Front of the Yugoslavs in Bulgaria, Sofia, 1946.</ref> As result on 7 October 1946, under pressure from [[Moscow]],<ref>P. H. Liotta, Dismembering the State: The Death of Yugoslavia and why it Matters. G - Reference, Lexington Books, 2001, {{ISBN|0739102125}}, p. 292.</ref> as part of the policy to foster the development of Macedonian national consciousness, Delchev's remains were transported to [[Skopje]].<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZmesOn_HhfEC&pg=PA68 |

|||

|title=The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world |

|||

| author=Loring M. Danforth |

|||

| publisher=Princeton University Press |

|||

|year=1997 |

|||

|isbn=0691043566 |

|||

|page=68 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011}} |

|||

</ref> On the occasion of sending the remains, the [[regent]] and a member of the [[Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and Arts]], [[Todor Pavlov]] presented a [[s:en:A speech by Todor Pavlov on the departure of Gotse Delchev's remains for Skopje - 1946|speech]] on a solemn assembly held in the [[Ivan Vazov National Theatre|National Theater in Sofia]].<ref>[http://www.promacedonia.org/mm/mm_1946_1_1.htm сп. Македонска мисъл, кн. 1-2, год. 2, 1946, Тодор Павлов, Гоце Делчев.]</ref> On 10 October, the bones were enshrined in a marble sarcophagus in the yard of the church [[Church of the Holy Salvation, Skopje|"Sveti Spas"]], where they have remained since.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h_LBmnBl99QC&pg=PA292 |

|||

|title=Dismembering the state: the death of Yugoslavia and why it matters |

|||

|author=P. H. Liotta |

|||

|year=2001 |

|||

|isbn=0739102125 |

|||

|page=292 |

|||

|publisher=Lexington Books |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011}} |

|||

</ref> At the time of the [[Tito–Stalin split]] in 1948, [[People's Republic of Bulgaria|Bulgaria]] broke its relationship with [[SFR Yugoslavia|Yugoslavia]] because "nationalist elements" had "managed to reach a dominant position in the leadership" of the [[CPY]]. The then Macedonian communist elite discussed the idea to scrap the name of Gotse Delchev from the [[Denes nad Makedonija|anthem of the country]], as he was suspected again of being [[Bulgarophile]] element, but this idea was finally abandoned.<ref>Последното интервју на Мише Карев: Колишевски и Страхил Гигов сакале да ги прогласат Гоце, Даме и Никола за Бугари! [https://denesen.mk/poslednoto-intervju-na-mishe-karev-kolishevski-i-strahil-gigov-sakale-da-gi-proglasat-goce-dame-i-nikola-za-bugari/ Денешен весник, 01.07.2019].</ref> Afterwards Bulgaria gradually shifted to its previous view, that Macedonian Slavs are in fact [[Bulgarians]].<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZmesOn_HhfEC&pg=PA68 |

|||

|title=The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World |

|||

| author=Loring M. Danforth |

|||

| publisher=Princeton University Press |

|||

| year=1997 |

|||

| isbn=0691043566 |

|||

|page=68 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011}} |

|||

</ref> Yugoslav authorities, after realizing that the Balkan collective memory had already accepted as Bulgarians the heroes of the Macedonian revolutionary movement, exerted efforts to claim Delchev for the Macedonian national cause.<ref>Livanios, Dimitris. ''The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939–1949''. Oxford Historical Monographs, Oxford University Press US, 2008, {{ISBN|0199237689}}, p. 202. |

|||

</ref> They started measures that would overcome the pro-Bulgarian feeling among parts of its population.<ref name="Djokic">{{cite book |

|||

| last =Djokić |

|||

| first =Dejan |

|||

| title =Yugoslavism: Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918–1992 |

|||

| publisher =C. Hurst & Co. |

|||

| year =2003 |

|||

| page =122 |

|||

| isbn =1850656630 }} |

|||

</ref> The new Communist authorities persecuted systematically and exterminated the right-wing nationalists with the charges of "great-Bulgarian chauvinism".<ref>Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Chris Kostov , Peter Lang, 2010, {{ISBN|3034301960}}, p. 84.</ref> The next task was persecution of older left-wing politicians, who were at some degree pro-Bulgarian oriented. They were purged from their positions, arrested and imprisoned.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=1jSg3lxgSy8C&pg=PA16&lpg=PA16&dq=the+second+session+asnom+lazar&source=bl&ots=wUpBqNDmW3&sig=9YdE95VMyj9BWM39iDLrWcN-xz8&hl=bg#v=onepage&q=second%20session%20asnom&f=false Historical dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia], Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, {{ISBN|0-8108-5565-8}}, pp. 15-16.</ref> |

|||

After realizing that the Balkan collective memory had already accepted the heroes of the Macedonian revolutionary movement as Bulgarians, Yugoslav authorities exerted efforts to claim Delchev for the Macedonian national cause.<ref>Livanios, Dimitris. ''The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939–1949''. Oxford Historical Monographs, Oxford University Press US, 2008, {{ISBN|0199237689}}, p. 202. |

|||

As a consequence, ''Bulgarophobia'' increased in [[Vardar Macedonia]] to the level of [[state ideology]].<ref>{{cite web |

|||

</ref> Aiming to enforce the belief that Delchev was an ethnic [[Macedonians (ethnic group)|Macedonian]], all documents written by him in standard [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] were translated into standard [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]], and presented as originals.<ref>{{cite book |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P-1m1FLtrvsC&pg=PA95 |chapter=Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996 |title=Nationalisms Across the Globe |author1=Chris Kostov |author2=Peter Lang |year=2010 |isbn=978-3034301961 |page=95 |access-date=20 November 2011}}</ref> As a result, Delchev was declared an ethnic Macedonian hero, and Macedonian school textbooks began even to hint at [[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] complicity in his death.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=http://www.newbalkanpolitics.org.mk/OldSite/Issue_6/editorial.eng.asp |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ppbuavUZKEwC&pg=PA117 |title=Who are the Macedonians? |author=Hugh Poulton |year=2000 |isbn=1850655340 |page=117 |publisher=C. Hurst & Co. |access-date=20 November 2011}}</ref> In the [[People's Republic of Bulgaria]], before 1960, Delchev was given mostly regional recognition in [[Pirin Macedonia]]. Afterwards, orders from the highest political level were given to reincorporate the Macedonian revolutionary movement as part of the Bulgarian historiography and to prove the Bulgarian credentials of its historical leaders. Since 1960, there have been long unproductive debates between the ruling Communist parties in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia about the ethnic affiliation of Delchev. Delchev was described in SR Macedonia not only as an anti-Ottoman freedom fighter, but also as a hero, who had opposed the aggressive aspirations of the pro-Bulgarian factions in the liberation movement.<ref>From recognition to repudiation: Bulgarian attitudes on the Macedonian question, articles, speeches, documents. Vanǵa Čašule, Kultura, 1972, p. 96.</ref> The claims on Delchev's [[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] self-identification, thus were portrayed as a recent Bulgarian chauvinist attitude of long provenance.<ref>The historiography of Yugoslavia, 1965-1976, Savez društava istoričara Jugoslavije, Dragoslav Janković, The Association of Yugoslav Historical Societies, 1976, pp. 307–310.</ref> Nonetheless, the Bulgarian side made in 1978 for the first time the proposal that some historical personalities (e.g. Gotse Delchev) could be regarded as belonging to the shared historical heritage of the two peoples, but that proposal did not appeal to the [[SFR Yugoslavia|Yugoslavs]].<ref>Yugoslav — Bulgarian Relations from 1955 to 1980 by Evangelos Kofos from J. Koliopoulos and J. Hassiotis (editors), Modern and Contemporary Macedonia: History, Economy, Society, Culture, vol. 2, (Athens-Thessaloniki, 1992), pp. 277–280.</ref> |

|||

|title=With the eyes of the "others" – about Macedonian-Bulgarian relations and the Macedonian national identity. |

|||

|editor=Mirjana Maleska |

|||

|work=New Balkan Politics – Journal of Politics. Issue 6 |

|||

|publisher=Newbalkanpolitics.org.mk |

|||

|date=3 February 2002 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011 |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070924172406/http://www.newbalkanpolitics.org.mk/OldSite/Issue_6/editorial.eng.asp |

|||

|archive-date=24 September 2007 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> Aiming to enforce the belief Delchev was an ethnic [[Macedonians (ethnic group)|Macedonian]], all documents written by him in standard [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] were translated into standardized in 1945 [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]], and presented as originals.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P-1m1FLtrvsC&pg=PA95 |

|||

|chapter=Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996 |

|||

|title=Nationalisms Across the Globe |

|||

|author1=Chris Kostov |author2=Peter Lang |year=2010 |

|||

|isbn=978-3034301961 |

|||

|page=95 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011}} |

|||

</ref> The new rendition of history reappraised the 1903 [[Ilinden Uprising]] as an anti-Bulgarian revolt.<ref>Gold, Gerald L. ''Minorities and mother country imagery'', Memorial University of Newfoundland. Institute of Social and Economic Research, 1984, {{ISBN|0919666434}}, p. 74. |

|||

</ref> The past was systematically falsified to conceal the truth, that most of the well-known [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonians]] had felt themselves to be Bulgarians.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iw9PHRR1oe4C&q=history+of+the+macedonian+language&pg=PA89 |

|||

|title=Yugoslavia: a concise history, Leslie Benson, Palgrave Macmillan, 2001, p. 89 |

|||

|isbn=0333792416 |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011|last1=Benson |

|||

|first1=Leslie |

|||

|date=10 October 2001 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> As result, Delchev was declared an ethnic Macedonian hero, and Macedonian school textbooks began even to hint at [[Principality of Bulgaria|Bulgarian]] complicity in his death.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ppbuavUZKEwC&pg=PA117 |

|||

|title=Who are the Macedonians? |

|||

|author=Hugh Poulton |

|||

|year=2000 |

|||

|isbn=1850655340 |

|||

|page=117 |

|||

|publisher=C. Hurst & Co. |

|||

|access-date=20 November 2011}} |

|||

</ref> This new ''Delchev myth'' was largely the creation of the Yugoslav communists, hence it would hardly have been in the interests of the pre-WWII Yugoslav authorities to promote it. To Yugoslav communists he was the ideal hero around which to build the Macedonian nation.<ref>Will Myer, People of the Storm God: Travels in Macedonia, Lost and found series, Signal Books, 2005, {{ISBN|1902669924}}, p. 106.</ref> In the [[People's Republic of Bulgaria]], the situation was more complex, and before 1960 Delchev was given mostly regional recognition in [[Pirin Macedonia]]. Afterwards, orders from the highest political level were given to reincorporate the Macedonian revolutionary movement as part of the Bulgarian historiography, and to prove the Bulgarian credentials of its historical leaders. SInce 1960, there have been long-going unproductive debates between the ruling Communist parties in Bulgaria and the Yugoslavia about the ethnic affiliation of Delchev. Delchev was described in [[SR Macedonia]] not only as an anti-Ottoman freedom fighter, but also as a hero, who had opposed the aggressive aspirations of the pro-Bulgarian factions in the liberation movement.<ref>From recognition to repudiation: Bulgarian attitudes on the Macedonian question, articles, speeches, documents. Vanǵa Čašule, Kultura, 1972, p. 96. |

|||

</ref> The claims on Delchev's [[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] self-identification, thus were portrayed as recent Bulgarian chauvinist attitude of long provenance.<ref>The historiography of Yugoslavia, 1965-1976, Savez društava istoričara Jugoslavije, Dragoslav Janković, The Association of Yugoslav Historical Societies, 1976, pp. 307–310.</ref> Nonetheless, the Bulgarian side made in 1978 for the first time the proposal that some historical personalities (e.g. Gotse Delchev) could be regarded as belonging to the shared historical heritage of the two peoples, but that proposal did not appeal to the [[SFR Yugoslavia|Yugoslavs]].<ref>Yugoslav — Bulgarian Relations from 1955 to 1980 by Evangelos Kofos from J. Koliopoulos and J. Hassiotis (editors), Modern and Contemporary Macedonia: History, Economy, Society, Culture, vol. 2, (Athens-Thessaloniki, 1992), pp. 277–280.</ref> |

|||

=== After the Fall of communism === |

=== After the Fall of communism === |

||

Revision as of 22:45, 6 February 2023

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (August 2020) |

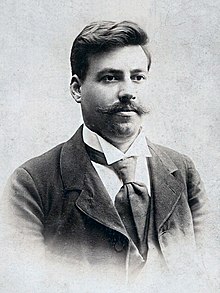

Voivode Gotse Delchev | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Gotse Delchev in Sofia c. 1900 | |

| Native name | Гоце Делчев |

| Birth name | Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Георги Николов Делчев) |

| Born | 4 February 1872 Kukush,[1] Salonica Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (now Kilkis, Greece) |

| Died | 4 May 1903 (aged 31) Banitsa, Salonika Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (now Greece) |

| Buried | Banitsa (1903-1913) Xanthi (1913-1919) Plovdiv (1919-1923) Sofia (1923-1946) Church of the Ascension of Jesus, Skopje (since 1946) |

| Service | Bulgarian army[2] Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (later SMARO, IMARO, IMRO) Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee |

| Alma mater | Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki Military School of His Princely Highness |

| Other work | Teacher |

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Bulgarian/Macedonian: Георги/Ѓорѓи Николов Делчев; 4 February 1872 – 4 May 1903), known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev (Гоце Делчев, originally spelled in older Bulgarian orthography as Гоце Дѣлчевъ),[3] was an important Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji),[note 1][note 2][note 3][note 4] active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions at the turn of the 20th century.[4][5][6] He was the most prominent leader of what is known today as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a secret revolutionary society[7] that was active in Ottoman territories in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.[8] Delchev was its representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria.[9] As such, he was also elected a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC),[10][11] participating in the work of its governing body.[12] He was killed in a battle with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Born into a Bulgarian family in Kilkis,[13][14] then in the Salonika Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire, in his youth he was inspired by the ideals of earlier Bulgarian revolutionaries such as Vasil Levski and Hristo Botev,[15] who envisioned the creation of a Bulgarian republic of ethnic and religious equality, as part of an imagined Balkan Federation.[16] Delchev completed his secondary education in the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki and entered the Military School of His Princely Highness in Sofia, but he was dismissed from there, only a month before his graduation, because of his leftist political persuasions. Then he returned to Ottoman Macedonia as a Bulgarian teacher,[17] and immediately became an activist of the newly-found revolutionary movement in 1894.[18]

Although considering himself to be an inheritor of the Bulgarian revolutionary traditions,[19] as a committed republican Delchev was disillusioned by the reality in the post-liberation Bulgarian monarchy.[20] Also by him, as by many Macedonian Bulgarians, originating from an area with mixed population,[21] the idea of being ‘Macedonian’ acquired the importance of a certain native loyalty, that constructed a specific spirit of "local patriotism"[22][23] and "multi-ethnic regionalism".[24][25] He maintained the slogan promoted by William Ewart Gladstone, "Macedonia for the Macedonians", including all different nationalities inhabiting the area.[26][27] In this way, his outlook included a wide range of such disparate ideas as Bulgarian patriotism, Macedonian regionalism, anti-nationalism, and incipient socialism.[28] As a result, his political agenda became the establishment through revolution of an autonomous Macedono-Adrianople supranational state into the framework of the Ottoman Empire,[29] as a prelude to its incorporation within a future Balkan Federation.[30] Despite he had been educated in the spirit of Bulgarian nationalism, he revised the Organization's statute, where the membership was restricted only for Bulgarians.[31] In this way he emphasized the importance of the cooperation among all ethnic groups in the territories concerned in order to obtain political autonomy.[32]

Today Gotse Delchev is considered as a national hero in Bulgaria,[33] as well as in North Macedonia, where it is claimed that he was among the founders of the Macedonian national movement.[34] Macedonian historians insist that the historical myth of Delchev there is so significant that it is more important than all the historical researches and documents,[35] and therefore his (Bulgarian) ethnic identification[36] should not be discussed.[37] Despite such controversial[38][39] Macedonian historical interpretations,[40][41] Delchev had clear Bulgarian ethnic identity[42][43] and viewed his compatriots as Bulgarians.[44] Some leading modern Macedonian historians, public intellectuals and politicians have recognized this begrudgingly[45][46] or even openly acknowledged that fact.[47] The designation Macedonian according to the then used ethnic terminology was an umbrella term, used for the local nationalities,[48][49] and when applied to the local Slavs, it meant a regional Bulgarian identity.[50][51] Opposite to the Macedonian claims, at that time even some IMRO revolutionaries natives from Bulgaria, as Delchev's friend Peyo Yavorov,[52] espoused Macedonian political identity.[53] However, his autonomist ideas of a separate Macedonian (and Adrianopolitan) political entity, have stimulated the subsequent development of Macedonian nationalism.[54] Nevertheless, some researchers doubt, that behind the IMRO idea of autonomy was hidden a reserve plan for eventual incorporation into Bulgaria,[55][56][57] backed by Delchev himself.[58] However, other researchers find the identity of Delchev and other major figures to be "open to different interpretations", [59] that are incompatible to the views of modern Balkan nationalisms.[60]

Biography

Early life

He was born to a large family on 4 February 1872 (23 January according to the Julian calendar) in Kılkış (Kukush), then in the Ottoman Empire (today in Greece). By the mid-19th century, Kılkış was populated predominantly with Macedonian Bulgarians[61][62][63][64] and became one of the centres of the Bulgarian national revival.[65][66] During the 1860s and 1870s it was under the jurisdiction of the Bulgarian Uniate Church,[67][68] but after 1884 most of its population gradually joined the Bulgarian Exarchate.[69][70] As a student, Delchev studied first at the Bulgarian Uniate primary school and then at the Bulgarian Exarchate junior high school.[71] He also read widely in the town's chitalishte, where he was impressed with revolutionary books, and was especially imbued with thoughts of the liberation of Bulgaria.[72] In 1888 his family sent him to the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki, where he organized and led a secret revolutionary brotherhood.[73] Delchev also distributed revolutionary literature, which he acquired from the school's graduates who studied in Bulgaria. Graduation from high school was faced with few career prospects and Delchev decided to follow the path of his former school-mate Boris Sarafov, entering the military school in Sofia in 1891. He at first encountered the newly independent Bulgaria full of idealism and dedication, but he later became disappointed with the commercialized life of the society and with the authoritarian politics of the prime minister Stefan Stambolov, accused of being a dictator.[74]

Gotsе spent his leaves in the company of emigrants from Macedonia. Most of them belonged to the Young Macedonian Literary Society. One of his friends was Vasil Glavinov, a leader of the Macedonian-Adrianople faction of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers Party. Through Glavinov and his comrades, he came into contact with different people, who offered a new forms of social struggle. In June 1892, Delchev and the journalist Kosta Shahov, a chairman of the Young Macedonian Literary Society, met in Sofia with the bookseller from Thessaloniki, Ivan Hadzhinikolov. Hadzhinikolov disclosed on this meeting his plans to create a revolutionary organization in Ottoman Macedonia. They discussed together its basic principles and agreed fully on all scores. Delchev explained, he has no intention of remaining an officer and promised after graduating from the Military School, he will return to Macedonia to join the organization.[76] In September 1894, only a month before graduation, he was expelled because of his political activity as a member of an illegal socialist circle.[77] He was given a possibility to enter the Army again through re-applying for a commission, but he refused. Afterwards he returned to European Turkey to work there as a Bulgarian teacher, aiming to get involved into the new liberation movement. At that time IMRO was in its early stages of development, forming its committees around the Bulgarian Exarchate schools.[78]

Teacher and revolutionary

Meanwhile, in Ottoman Thessaloniki a revolutionary organization was founded in 1893, by a small band of anti-Ottoman Macedono-Bulgarian revolutionaries, including Hadzhinikolov. At this time the name of the organization was Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC), in 1902 changed to Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (SMARO).[80][81] It was decided at a meeting in Resen in August 1894 to preferably recruit teachers from the Bulgarian schools as committee members.[82] In the autumn of 1894 Delchev became teacher in an Exarchate school in Štip, where he met another teacher: Dame Gruev, who was also a leader of the newly established local committee of BMARC.[83] As a result of the close friendship between the two, Delchev joined the organization immediately, and gradually became one of its main leaders. After this, both Gruev and Delchev worked together in Štip and its environs. At the same time, the Organization developed quickly and had managed to begin establishing a network of local organizations across Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet, usually centered around the schools of the Bulgarian Exarchate.[84] The expansion of the BMARC at the time was considerable, particularly after Gruev settled in Thessaloniki during the years 1895–1897, in the quality of a Bulgarian school inspector. Under his direction, Delchev travelled during the vacations throughout Macedonia and established and organized committees in villages and cities. Delchev also established contacts with some of the leaders of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC). Its official declaration was a struggle for autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace.[85] However, as a rule, most of SMAC's leaders were officers with stronger connections with the governments, waging terrorist struggle against the Ottomans in the hope of provoking a war and thus Bulgarian annexation of both areas. He arrived illegally in Bulgaria's capital and tried to get support from the SMAC's leadership. Delchev had a number of meetings with Danail Nikolaev, Yosif Kovachev, Toma Karayovov, Andrey Lyapchev and others, but he was often frustrated of their views. As a whole, Delchev had a negative attitude towards their activities. After spending the next school year (1895/1896) as a teacher in the town of Bansko, in May 1896 he was arrested by the Ottoman authorities as person suspected in revolutianary activity and spent about a month in jail. Later Delchev participated in the Thessaloniki Congress of BMARC in the Summer. Afterwards, Delchev gave his resignation as teacher and, in the Autumn of 1896, he moved back to Bulgaria, where he, together with Gyorche Petrov, served as a foreign representatives of the organization in Sofia.[86] At that time the organization was largely dependent on the Bulgarian state and army assistance, that was mediated by the foreign representatives.

Revolutionary activity as part of the leadership of the Organization

Delchev's involvement in BMARC was an important moment in the history of the Macedonian-Adrianople liberation movement.[87] The years between the end of 1896, when he left the Exarchate's educational system and 1903 when he died, represented the final and most effective revolutionary phase of his short life. In the period 1897–1902 he was a representative of the Foreign Committee of the BMARC in Sofia. Again in Sofia, negotiating with suspicious politicians and arms merchants, Delchev saw more of the unpleasant face of the Principality, and became even more disillusioned with its political system. In 1897 he, along with Gyorche Petrov, wrote the new organization's statute, which divided Macedonia and Adrianople areas into seven regions, each with a regional structure and secret police, following the Internal Revolutionary Organization's example. Below the regional committees were districts.[88] The Central committee was placed in Thessaloniki. In 1898 Delchev decided to be created a permanent acting armed bands (chetas) in every district. From 1902 till his death he was the leader of the chetas, i.e. the military institute of the Organization because, he had considerable knowledge in the area of military skills.[89] Delchev ensured the functioning of the underground border crossings of the organization and the arms depots added to them, alongside the then Bulgarian-Ottoman border.

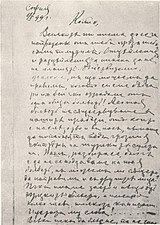

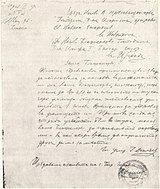

His correspondence with other BMARC/SMARO members covers extensive data on supplies, transport and storage of weapons and ammunition in Macedonia. Delchev envisioned independent production of weapons, and traveled in 1897 to Odessa, where he met with Armenian revolutionaries Stepan Zorian and Christapor Mikaelian to exchange terrorist skills and especially bomb-making.[90] That resulted in the establishment of a bomb manufacturing plant in the village of Sabler near Kyustendil in Bulgaria. The bombs were later smuggled across the Ottoman border into Macedonia.[91] Gotse Delchev was the first to organize and lead a band into Macedonia with the purpose of robbing or kidnapping rich Turks. His experiences demonstrate the weaknesses and difficulties which the Organization faced in its early years.[92] Later he was one of the organizers of the Miss Stone Affair. He made two short visits to the Adrianople area of Thrace in 1896 and 1898.[93] In the winter of 1900 he resided for a while in Burgas, where Delchev organized another bomb manufacturing plant, which dynamite was used later by the Thessaloniki bombings.[94] In 1900 he inspected also the BMARC's detachments in Eastern Thrace again, aiming better coordination between Macedonian and Thracian revolutionary committees. After the assassination in July of the Romanian newspaper editor Ștefan Mihăileanu, who had published unflattering remarks about the Macedonian affairs, Bulgaria and Romania were brought to the brink of war. At that time Delchev was preparing to organize a detachment which, in a possible war to support the Bulgarian army by its actions in Northern Dobruja, where compact Bulgarian population was available.[95][96] Since the Autumn of 1901 till the early Spring of 1902, he made an important inspection in Macedonia, touring all revolutionary districts there. He led also the congress of the Adrianople revolutionary district held in Plovdiv in April 1902. Afterwards Delchev inspected the BMARC's structures in the Central Rhodopes. The inclusion of the rural areas into the organizational districts contributed to the expansion of the organization and the increase in its membership, while providing the essential prerequisites for the formation of the military power of the organization, at the same time having Delchev as its military advisor (inspector) and chief of all internal revolutionary bands.[97]

After 1897 there was a rapid growth of secret Officer's brotherhoods, whose members by 1900 numbered about a thousand.[98] Much of the Brotherhoods' activists were involved in the revolutionary activity of the BMARC.[99] Among the main supporters of their activities was Gotse Delchev.[100] Delchev aimed also better coordination between BMARC and the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee. For a short time in the late 1890s lieutenant Boris Sarafov, who was former school-mate of Delchev became its leader. At that period the foreign representatives Delchev and Petrov became by rights members of the leadership of the Supreme Committee and so BMARC even managed to gain de facto control of the SMAC.[101] Nevertheless, it soon split into two factions: one loyal to the BMARC and one led by some officers close to the Bulgarian prince. Delchev opposed this officers' insistent attempts to gain control over the activity of BMARC.[102] Sometimes SMAC even clashed militarily with local SMARO bands as in the autumn of 1902. Then the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee organized a failed uprising in Pirin Macedonia (Gorna Dzhumaya), which merely served to provoke Ottoman repressions and hampered the work of the underground network of SMARO.

The primary question regarding the timing of the uprising in Macedonia and Thrace implicated an apparent discordance not only among the SMAC and the SMARO, but also among the SMARO's leadership. At the Thessaloniki Congress of January 1903, where Delchev did not participate, an early uprising was debated and it was decided to stage one in the Spring of 1903. This led to fierce debates among the representatives at the Sofia SMARO's Conference in March 1903. By that time two strong tendencies had crystallized within the SMARO. The right-wing majority was convinced that if the Organization would unleash a general uprising, Bulgaria would be provoked to declare war of the Ottomans and after the subsequent intervention of the Great Powers the Empire would collapse.[103]

Delchev also launched the establishment of a secret revolutionary network, that would prepare the population for an armed uprising against the Ottoman rule.[104] Delchev opposed the IMRO Central Committee's plan for a mass uprising in the summer of 1903, favoring terrorist and guerilla tactics. Deltchev, who was under the influence of the leading Bulgarian anarchists as Mihail Gerdzhikov and Varban Kilifarski personally opposed the IMRO Central Committee's plan for a mass uprising in the summer of 1903, instead supporting the tactics of terrorist and guerilla tactics such as the Thessaloniki bombings of 1903.[105][106] Finally, he had no choice but agree to that course of action at least managing to delay its start from May to August. Delchev also convinced the SMARO leadership to transform its idea of a mass rising involving the civil population into a rising based on guerrilla warfare. Towards the end of March 1903 Gotse with his detachment destroyed the railway bridge over the Angista river, aiming to test the new guerrilla tactics. Following that he set out for Thessaloniki to meet with Dame Gruev after his release from prison in March 1903. Dame Gruev met with Delchev in the late April and they discussed the decision of starting the uprising. Afterwards they negotiated with some of the Thessaloniki bombers to ask them to give up the attacks as dangerous to the liberation movement, or at least to wait for the impending uprising.[107] Subsequently, Delchev met also with Ivan Garvanov, who was at that time the leader of the SMARO.[108] After this meetings Delchev headed for Mount Ali Botush where he was expected to meet with representatives from the Serres Revolutionary District detachments and to check their military preparation. But he never arrived.

Death and aftermath

Meanwhile, on 28 April, members of the Gemidzii circle started terrorist attacks in Thessaloniki. As a consequence martial law was declared in the city and many Turkish soldiers and "bashibozouks" were concentrated in the Salonica Vilayet. This led eventually to the tracking of Delchev's cheta and his subsequent death.[110] He died on 4 May 1903, in a skirmish with the Turkish police near the village of Banitsa, probably after betrayal by local villagers, as rumours asserted, while preparing the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising.[111] Thus the liberation movement lost its most important organizer, at the eve of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising. After being identified by the local authorities in Serres, the bodies of Delchev and his comrade, Dimitar Gushtanov, were buried in a common grave in Banitsa. Soon afterwards SMARO, aided by SMAC organized the uprising against the Ottomans, which after initial successes, was crushed with much loss of life.[112] Two of his brothers, Mitso Delchev and Milan Delchev were also killed fighting against the Ottomans as militants in the SMARO chetas of the Bulgarian voivodas Hristo Chernopeev and Krstjo Asenov in 1901 and 1903, respectively. In 1914, by a royal decree of Tsar Ferdinand I, a pension for life was granted to their father Nikola Delchev, because of the contribution of his sons to the freedom of Macedonia.[113] During the Second Balkan War of 1913, Kilkis, which had been annexed by Bulgaria in the First Balkan War, was taken by the Greeks. Virtually all of its pre-war 7,000 Bulgarian inhabitants, including Delchev's family, were expelled to Bulgaria by the Greek Army.[114] The same happened to the population of Banitsa, the village where Delchev was buried.[115] During Balkan Wars, when Bulgaria was temporarily in control of the area, Delchev's remains were transferred to Xanthi, then in Bulgaria. After Western Thrace was ceded to Greece in 1919, the relic was brought to Plovdiv and in 1923 to Sofia, where it rested until after World War II.[116] During World War II, the area was taken by the Bulgarians again and Delchev's grave near Banitsa was restored.[117] In May 1943, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of his death, a memorial plaque was set in Banitsa, in the presence of his sisters and other public figures.[118][119] Until the end of the WWII Delchev was considered one of the greatest Bulgarians in the region of Macedonia.[120]

The first biographical book about Delchev was issued in 1904 by his friend and comrade in arms, the Bulgarian poet Peyo Yavorov.[121] The most detailed biography of Delchev in English is written by Mercia MacDermott: "Freedom or Death: The Life of Gotse Delchev".[122]

Controversy

During the Cold war

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (August 2020) |

In 1934 the Comintern gave its support to the idea that the Macedonian Slavs constituted a separate nation.[123] Prior to the Second World War, this view on the Macedonian issue had been of little practical importance. However, during the war these ideas were supported by the pro-Yugoslav Macedonian communist partisans, who strengthened their positions in 1943, referring to the ideals of Gotse Delchev.[citation needed] After the Red Army entered the Balkans in late 1944, new communist regimes came into power in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. In this way their policy on the Macedonian Question was committed to the Comintern policy of supporting the development of a distinct ethnic Macedonian consciousness.[124][125] The region of Macedonia was proclaimed as the connecting link for the establishment of a future Balkan Communist Federation. The newly established Yugoslav People's Republic of Macedonia, was characterized as the natural result of Delchev's aspirations for autonomous Macedonia.[126]

However, initially, he was proclaimed by its Communist leader Lazar Koliševski as: "...one Bulgarian of no significance for the liberation struggles...".[127] But at the beginning of 1946, a conference of the Macedonian Communists was held, at which Vasil Ivanovski presented a report entitled "Current Issues in Macedonia". The report claimed that Gotse may have considered himself and the Macedonian Slavs Bulgarians, but he was not clear about the ethnic character of the Macedonians.[128] As a result on 7 October 1946, under pressure from Moscow,[129] as part of the policy to foster the development of Macedonian national consciousness, Delchev's remains were transported to Skopje.[130] On the occasion of sending the remains, the regent and a member of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Todor Pavlov presented a speech on a solemn assembly held in the National Theater in Sofia.[131][relevant?] On 10 October, the bones were enshrined in a marble sarcophagus in the yard of the church "Sveti Spas", where they have remained since.[132] Delchev's name became part of the anthem of SR Macedonia - Today over Macedonia.[133] After the Tito–Stalin split in 1948, the then Macedonian communist elite discussed the idea to scrap the name of Delchev from the anthem of the country, as he was suspected again of being Bulgarophile element, but this idea was finally abandoned.[134]

After realizing that the Balkan collective memory had already accepted the heroes of the Macedonian revolutionary movement as Bulgarians, Yugoslav authorities exerted efforts to claim Delchev for the Macedonian national cause.[135] Aiming to enforce the belief that Delchev was an ethnic Macedonian, all documents written by him in standard Bulgarian were translated into standard Macedonian, and presented as originals.[136] As a result, Delchev was declared an ethnic Macedonian hero, and Macedonian school textbooks began even to hint at Bulgarian complicity in his death.[137] In the People's Republic of Bulgaria, before 1960, Delchev was given mostly regional recognition in Pirin Macedonia. Afterwards, orders from the highest political level were given to reincorporate the Macedonian revolutionary movement as part of the Bulgarian historiography and to prove the Bulgarian credentials of its historical leaders. Since 1960, there have been long unproductive debates between the ruling Communist parties in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia about the ethnic affiliation of Delchev. Delchev was described in SR Macedonia not only as an anti-Ottoman freedom fighter, but also as a hero, who had opposed the aggressive aspirations of the pro-Bulgarian factions in the liberation movement.[138] The claims on Delchev's Bulgarian self-identification, thus were portrayed as a recent Bulgarian chauvinist attitude of long provenance.[139] Nonetheless, the Bulgarian side made in 1978 for the first time the proposal that some historical personalities (e.g. Gotse Delchev) could be regarded as belonging to the shared historical heritage of the two peoples, but that proposal did not appeal to the Yugoslavs.[140]

After the Fall of communism

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (August 2020) |

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia and the fall of Communism, some new attempts were made from Bulgarian officials for joint celebration with the newly established Republic of Macedonia, of the common IMRO heroes, e.g. Delchev, but they all were rejected as politically unacceptable, and as threatening the Macedonian national identity.[145][146][147]

Recently the Macedonian political elite has been interested in a debate about the national historical narrative with Bulgaria in relation with its frozen candidatures for joining the European Union and NATO membership. On 2 August 2017, the Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov and his Macedonian colleague Zoran Zaev placed wreaths at the grave of Gotse Delchev on the occasion of the 114th anniversary of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, after the previous day, both have signed a treaty for friendship and cooperation between the neighboring states.[148] On its ground a joint commission on historical issues was formed in 2018. This intergovernmental commission is a forum where controversial historical issues are raised, to resolve the problematic readings. However, the commission has made a little progress for one year, due to a Macedonian opposition and especially in the case of Delchev. The Bulgarian part of the commission pointed to Delchev's own writings, where he declared himself as a Bulgarian, and clarified the fact that Delchev had Bulgarian identity, doesn't mean that North Macedonia has no right to honour him as its own national hero, and both countries may celebrate him as a common historical figure. However the historians from Macedonian side maintained, that if they "surrender" Gotse, the Macedonian national identity would go bust.[149] Practically since its creation, the Macedonian historiography held as its central principle, that Macedonian history is distinctively different from that of Bulgaria and its primary goal was to build a separate Macedonian consciousness, based on "anti-Bulgarian" basis, and to sever any ties with Bulgarian people.[150] In fact, because in many documents from the 19th century the Macedonian Slavs were referred to as "Bulgarian", Macedonian scientists argue that they were "Macedonian", regardless of what is written in the records.[151] Macedonian member from the joint historical commission, has even stated that if Delchev would be recognized as Bulgarian, then his memory will not make sense to be honored there.[152] Another Macedonian member from the joint commission has openly claimed in a TV-interview, that there is no proof that Delchev ever identified as Bulgarian.[153]

As result on 9 June 2019 Bulgaria's Defence Minister, Krasimir Karakachanov, warned that the work of the joint history commission had "stalled" over the issue of Gotse Delchev. Subsequently, Bulgarian Foreign Minister Ekaterina Zaharieva warned North Macedonia, Bulgaria will withdraw from the joint commission, unless enough progress is made on the issue of Delchev's historical legacy. Finally, the PM Borisov declared on 20 June 2019 that anti-Bulgarian rhetoric and appropriation of Bulgaria's history as its own from North Macedonia "must stop".[154] On the same day North Macedonia's President Stevo Pendarovski warned about the tensions between the two countries over their history, and about possible Bulgarian block of North Macedonia's candidature in EU.[155] The PM Zoran Zaev replied that both countries need to mature together. Foreign Minister of North Macedonia, Nikola Dimitrov, said he expects an understanding will be reached between both countries on historical issues.[156] Thus Pendarovski publicly affirmed, that undoubtedly Delchev self-identified as a Bulgarian, compromising that: he supported the idea of an independent Macedonian state.[157] In fact, the idea about Independent Macedonia was a subsequent project from the interwar period.[158] Bulgarian politicians reacted positively to Pendarovski's statement, insisting however, that this only act is not enough and the bilateral commission must confirm the Bulgarian identity of many historical figures from 19th and first half of the 20th century.[159] According to the President Rumen Radev, Bulgaria will support North Macedonia's candidature in the EU, but it is important Skopje to end the embezzlement of Bulgarian history. The Foreign Minister Zaharieva added, that Delchev is a common hero, part of Bulgarian and Macedonian history. The fact, he was a Bulgarian, who struggled for the autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople regions, must unite both countries, not divide them. Afterwards PM Zaev has recognized that in the past Macedonia presented parts from the history of its Balkan neighbors as its own, but this process has been suspended.[160]

Surprisingly, in late September 2019, the President Pendarovski gave a new interview in which he gave up his words about Delchev. In it he implied that Delcev was pressured to falsely declare himself as a Bulgarian, while actually having an ethnic Macedonian identity. Pendarovski compared Delcev with present-day thousands of Macedonians who get Bulgarian citizenship, which allow them access to the EU, after they declare themselves as Bulgarians by origin. "I was felt sick when I saw the video", said Bulgarian MEP Andrey Kovatchev, who praised Pendarvski's former claims.[161] Bulgaria's reaction was not delayed. Its IMRO-BNM Deputy PM — Karakachanov, announced that Bulgaria must not to back the EU accession of the former Yugoslav republic: "until all falsifications of history have been cleared up".[162] As result in the early October, Bulgaria has set a lot of tough terms for North Macedonia's EU progress. The Bulgarian government accepted an ultimate "Framework Position", where has warned that Bulgaria will not allow the EU integration of North Macedonia to be accompanied by European legitimization of an anti-Bulgarian ideology, sponsored by Skopje authorities. In the list are more than 20 demands and a timetable to fulfill them, during the process of North Macedonia's accession negotiations. Among others, Bulgaria insists on the recognition of the Bulgarian character of the IMRO itself, the Ilinden uprising, all the Macedonian revolutionaries from that time, including Delchev, etc. It states that the rewriting of the history of part of the Bulgarian people after 1944 was one of the pillars of the bulgarophobic agenda of then Yugoslav communism. Bulgarian National Assembly voted on 10 October and approved this "Framework Position" put forward by the government on the EU accession of North Macedonia.[163] On November 17, 2020, Bulgaria has blocked the official start of the EU accession talks with North Macedonia,[164] because of the ongoing historical negationism there, ignoring any Bulgarian identity, culture and legacy in the region of Macedonia.[165] Meanwhile, in Skopje have growed concerns, that the negotiations with Bulgaria over the "common history", may lead to rise of extreme nationalism, political crisis, and even internal clashes.

On February 4, 2023, on the 151st anniversary of the birth of the revolutionary, both the Macedonian and Bulgarian side paid their respects at the St. Spas Church in Skopje separately, while the delegation of North Macedonia declined the offer to jointly lay wreaths proposed by the Bulgarian delegation.[166] Many Bulgarian citizens who wanted to attend the event were held for hours at the border due to the malfunction of the border system.[167][168] However, problems with the admission of the Bulgarians continued even after the processing of their documents.[169] As a result, some Bulgarian citizens and journalists were prevented from crossing. Three citizens were detained, fined and banned from entering the country for 3 years, due to attempting to physically assault policemen.[170][171] According to their lawyer, two of them were apparently beaten.[172][173] Sofia officially reacted sharply to these events.[174]

Delchev's views

The international, cosmopolitan views of Delchev could be summarized in his proverbial sentence: "I understand the world solely as a field for cultural competition among the peoples".[177] In the late 19th century the anarchists and socialists from Bulgaria linked their struggle closely with the revolutionary movements in Macedonia and Thrace.[178] Thus, as a young cadet in Sofia Delchev became a member of a left circle, where he was strongly influenced by the modern than Marxist and Bakunin's ideas.[179] His views were formed also under the influence of the ideas of earlier anti-Ottoman fighters as Levski, Botev, and Stoyanov, who were among the founders of the Bulgarian Internal Revolutionary Organization, the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee and the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee, respectively.[180] Later he participated in the Internal organization's struggle and as well educated leader, became one of its theoreticians and co-author of the BMARC's statute from 1896.[181] Developing his ideas further in 1902 he took the step, together with other left functionaries, of changing its nationalistic character, which determined that members of the organization can be only Bulgarians. The new supra-nationalistic statute renamed it to Secret Macedono-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Organization (SMARO),[182] which was to be an insurgent organization, open to all Macedonians and Thracians regardless of nationality, who wished to participate in the movement for their autonomy.[183] This scenario was partially facilitated by the Treaty of Berlin (1878), according to which Macedonia and Adrianople areas were given back from Bulgaria to the Ottomans, but especially by its unrealized 23rd. article, which promised future autonomy for unspecified territories in European Turkey, settled with Christian population.[184] In general, an autonomous status was presumed to imply a special kind of constitution of the region, a reorganization of gendarmerie, broader representation of the local Christian population in it as well as in all the administration, similarly to what happened in the short-lived Eastern Rumelia. However, there was not a clear political agenda behind IMRO's idea about autonomy and its final outcome, after the expected dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.[185] Delcev, like other left-wing activists, vaguely determined the bonds in the future common Macedonian-Adrianople autonomous region on the one hand,[186] and on the other between it, the Principality of Bulgaria, and de facto annexed Eastern Rumelia.[187] Even the possibility that Bulgaria could be absorbed into a future autonomous Macedonia, rather than the reverse, was discussed.[188] It is claimed that the personal view of the convinced republican Delchev,[189] was much more likely to see inclusion in a future Balkan Confederative Republic,[190][191] or eventually an incorporation into Bulgaria.[192][193][194] Both ideas were probably influenced by the views of the founders of the organization.[195] The ideas of a separate Macedonian nation and language were as yet promoted only by small circles of intellectuals in Delchev's time,[196] and failed to gain wide popular support.[197] As a whole the idea of autonomy was strictly political and did not imply a secession from Bulgarian ethnicity.[198] In fact, for militants such as Delchev and other leftists, that participated in the national movement retaining a political outlook, national liberation meant "radical political liberation through shaking off the social shackles".[199] There aren't any indications suggesting his doubt about the Bulgarian ethnic character of the Macedonian Slavs at that time.[200] Delchev also used the Bulgarian standard language, and he was not in any way interested in the creation of separate Macedonian language.[201] The Bulgarian ethnic self-identification of Delchev has been recognized as from leading international researchers of the Macedonian Question,[202] as well as from part of the Macedonian historical scholarship and political elite, although reluctantly.[203][204][205][206] However, despite his Bulgarian loyalty, he was against any chauvinistic propaganda and nationalism.[207] According to him, no outside force could or would help the Organization and it ought to rely only upon itself and only upon its own will and strength.[208] He thought that any intervention by Bulgaria would provoke intervention by the neighboring states as well, and could result in Macedonia and Thrace being torn apart. That is why the peoples of these two regions had to win their own freedom, within the frontiers of an autonomous Macedonian-Adrianople state.[209]

Despite the efforts of the post-1945 Macedonian historiography to represent Delchev as a Macedonian separatist rather than a Bulgarian nationalist, Delchev himself has stated: "...We are Bulgarians and all suffer from one common disease [e.g., the Ottoman rule]" and "Our task is not to shed the blood of Bulgarians, of those who belong to the same people that we serve".[210]

Legacy

Delchev is today regarded both in Bulgaria and in North Macedonia as an important national hero, and both nations see him as part of their own national history.[212] His memory is honoured especially in the Bulgarian part of Macedonia and among the descendants of Bulgarian refugees from other parts of the region, where he is regarded as the most important revolutionary from the second generation of freedom fighters.[213] His name appears also in the national anthem of North Macedonia: "Denes nad Makedonija". There are two towns named in his honour: Gotse Delchev in Bulgaria and Delčevo in North Macedonia. There are also two peaks named after Delchev: Gotsev Vrah, the summit of Slavyanka Mountain, and Delchev Vrah or Delchev Peak on Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands in Antarctica, which was named after him by the scientists from the Bulgarian Antarctic Expedition. Delchev Ridge on Livingston Island bears also his name. The Goce Delčev University of Štip in North Macedonia carries his name too. Today many artifacts related to Delchev's activity are stored in different museums across Bulgaria and North Macedonia.

During the time of SFR Yugoslavia, a street in Belgrade was named after Delchev. In 2015, Serbian nationalists covered the signs with the street's name and affixed new ones with the name of the Chetniks' activist Kosta Pecanac. They claimed that Delchev was a Bulgarian and his name has no place there.[214] Though in 2016 the street's name was changed officially by the municipal authorities to Fyodor Tolbukhin, a Russian general who led the Belgrade operation at the end of the Second World War. Their motivation was that Delchev was not an ethnic Macedonian revolutionary, but an activist of an anti-Serbian organization with pro-Bulgarian orientation.[215]

In Greece the official appeals from Bulgarian side to the authorities to install a memorial plaque on his place of death are not answered. The memorial plaques set periodically by enthusiast Bulgarians afterwards are removed. Bulgarian tourists are restrained occasionally to visit the place.[216][217][218]

Memorials

-

Monument in Gotse Delchev, Bulgaria.

-

Monument in Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria.

-

The tomb of Gotse Delchev in the church Sv. Spas in Skopje, North Macedonia

Notes

- ^ Per Julian Allan Brooks' thesis the term ‘Macedo-Bulgarian’ refers to the Exarchist population in Macedonia which is alternatively called ‘Bulgarian’ and ‘Macedonian’ in the documents. For more see: Managing Macedonia: British Statecraft, Intervention and 'Proto-peacekeeping' in Ottoman Macedonia, 1902-1905. Department of History, Simon Fraser University, 2013, p. 18. The designation ‘Macedo-Bulgarian’ is used also by M. Şükrü Hanioğlu and Ryan Gingeras. See: M. Şükrü Hanioğlu, Preparation for a Revolution: The Young Turks, 1902-1908 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 244; Ryan Gingeras, “A Break in the Storm: Reconsidering Sectarian, Violence in Ottoman Macedonia During the Young Turk Revolution” The MIT Electronic Journal of Middle East Studies 3 (Spring 2003): 1. Gingeras notes he uses the hyphenated term to refer to those who “professed an allegiance to the Bulgarian Exarch.” Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu has used in his study "Yane Sandanski as a political leader in Macedonia in the era of the Young Turks" the terms Bulgarians-Macedonians and Bulgarian Macedonians; (Cahiers balkaniques [En ligne], 40, 2012, Jeunes-Turcs en Macédoine et en Ionie).

- ^ Per Loring Danforth's article about the IMRO in Encyclopedia Britannica Online, its leaders, including Delchev, had a dual identity - Macedonian regional and Bulgarian national. According to Paul Robert Magocsi in many circumstances this might seem a normal phenomenon, such as by the residents of the pre–World War II Macedonia, who identified as a Macedonian and Bulgarian (or "Macedono-Bulgarian"). Per Bernard Lory there were two different kinds of Bulgarian identity at the early 20th century: the first kind was a vague form that grew up during the 19th century Bulgarian National Revival and united most of the Macedonian and other Slavs in the Ottoman Empire. The second kind Bulgarian identity was the more concrete and strong and promoted by the authorities in Sofia among the Bulgarian population. Per Julian Allan Brooks' thesis there were some indications to suggest the existence of inchoate Macedonian national identity then, however the evidence is rather fleeting. For more see: Paul Robert Magocsi, Carpathian Rus': Interethnic Coexistence without Violence, p. 453, in Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands with editors, Omer Bartov, Eric D. Weitz, Indiana University Press, 2013, ISBN 0253006317, pp. 449-462.

- ^ Per John Van Antwerp Fine until the late 19th century both outside observers and those Macedonian Bulgarians who had an ethnic consciousness believed that their group, which is now two separate nationalities, comprised a single people, the Bulgarians. According to Loring M. Danforth at the end of the World War I there were very few historians or ethnographers, who claimed that a separate Macedonian nation existed. It seems most likely that at this time many of the Slavs of Macedonia in rural areas, had not yet developed a firm sense of national identity at all. Of those who had developed then some sense of national identity, the majority considered themselves to be Bulgarians... The question as of whether a Macedonian nation actually existed in the 1940s when a Communist Yugoslavia decided to recognize one is difficult to answer. Some observers argue that even at this time it was doubtful whether the Slavs from Macedonia considered themselves to be a nationality separate from the Bulgarians. Per Stefan Troebst Macedonian nation, language, literature, history and church were not available in 1944, but since the creation of the Yugoslav Macedonia they were accomplished in a short time. For more, see: "The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century," University of Michigan Press, 1991, ISBN 0472081497, pp. 36–37; One Macedonia With Three Faces: Domestic Debates and Nation Concepts, in Intermarium; Columbia University; Volume 4, No. 3 (2000–2001), pp. 7-8; The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-691-04356-6, pp. 65-66.

- ^ Today, Delchev's identity is the subject of a dispute between Bulgaria and North Macedonia. According to the Bulgarian historian Stefan Dechev, who often has criticized the official Bulgarian historiography on the Macedonian issue, and this gave him a sympathy in North Macedonia, the Macedonian side wants to emphasize the work of Delchev and especially its importance from today perspective. This stems from the fundamental historical myth built on him in Communist Yugoslavia. It is about the desire to keep the nation building delusion, that in Delchev's time, there was already formed Macedonian national identity, and to preserve the image of Bulgaria as a demonized enemy. Nonetheless, there was really a regional Macedonian political identity then, and there is evidence of its opposition to the Bulgarian state sponsored nationalist propaganda. However ethnically, all the leaders and the activists of the IMRO at that time were Bulgarians. On the other side, is the unacceptable position of the Bulgarian historians, who insist that there is no need to determine exactly what complex identity Delchev really had, given that he was ethnically a Bulgarian. For more see: Стефан Дечев: Българската и македонската интерпретации на документите за Гоце Делчев са користни и непрофесионални, Marginalia, 14.09.2019; Бугарскиот историчар Дечев: Македонскиот јазик не може да биде само едноставен дијалект или регионална форма. Дек. 16, 2019, МКД.мк.

References

- ^ For example, Gotse Delcev, a schoolmaster from Kukush (present-day Kilkis)... Anastasia Karakasidou, Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990, University of Chicago Press, 2009, ISBN 0226424995, p. 282.

- ^ In 1894 Gotse Delchev reached the rank of officer cadet of the Bulgarian Army, successfully completing a full course of study at the Military School in Sofia, but leaving it without being promoted to the first officer rank of lieutenant.

- ^ Гоце Дѣлчевъ. Биография. П.К. Яворовъ, 1904.

- ^ Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 0691188432, p. 174; Bernard Lory, The Bulgarian-Macedonian Divergence, An Attempted Elucidation, INALCO, Paris in Developing Cultural Identity in the Balkans: Convergence Vs. Divergence with Raymond Detrez and Pieter Plas as ed., Peter Lang, 2005, ISBN 9052012970, pp. 165-193.

- ^ The Making of a New Europe: R.W. Seton-Watson and the Last Years of Austria-Hungary, Hugh Seton-Watson, Christopher Seton-Watson, Methuen, 1981, ISBN 0416747302, p. 71.

- ^ Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. VII.

- ^ Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, written by Loring Danforth, an article in Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

- ^ Bechev, Dimitar (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6295-1., pp. 55-56

- ^ Angelos Chotzidis, Anna Panagiōtopoulou, Vasilis Gounaris, The events of 1903 in Macedonia as presented in European diplomatic correspondence. Volume 3 of Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, 1993; ISBN 9608530334, p. 60.

- ^ What was more, “the military” (SMAC) worked in close collaboration and mutual understanding with the “civilian” leaders of the IMARO. This is shown by the fact that, at the Sixth Macedonian Congress (held May 1–5, 1899), Sarafov was nominated for president and Gotse Delchev and Gyorche Petrov, external representatives of the “secret ones,” were elected full-right members of the SMAC. For more see: Peter Kardjilov, The Cinematographic Activities of Charles Rider Noble and John Mackenzie in the Balkans (Volume One); Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020, ISBN 1527550737, p. 5.

- ^ From 1899 to 1901, the supreme committee provided subsidies to IMRO' s central committee, allowances for Delchev and Petrov in Sofia, and weapons for bands sent to the interior. Delchev and Petrov were elected full members of the supreme committee. For more see: Laura Beth Sherman, Fires on the Mountain: The Macedonian Revolutionary Movement and the Kidnapping of Ellen Stone, East European monographs, 1980, ISBN 0914710559, p. 18.

- ^ Duncan M. Perry, The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903; Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, pp. 82-83.

- ^ Susan K. Kinnell, People in World History, Volume 1; An Index to Biographies in History Journals and Dissertations Covering All Countries of the World Except Canada and the U.S, ISBN 0874365503, ABC-CLIO, 1989; p. 157.

- ^ Delchev was born into a family of Bulgarian Uniates, who later switched to Bulgarian Еxarchists. For more see: Светозар Елдъров, Униатството в съдбата на България: очерци из историята на българската католическа църква от източен обред, Абагар, 1994, ISBN 9548614014, стр. 15.

- ^ Todorova, Maria N. Bones of Contention: The Living Archive of Vasil Levski and the Making of Bulgaria's National Hero, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776246, p. 76.

- ^ Jelavich, Charles. The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804-1920, University of Washington Press, 1986, ISBN 0295803606, pp. 137-138.

- ^ In Macedonia, the education race produced the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which organized and carried out the Ilinden Uprising of 1903. Most of IMRO's founders and principal organizers were graduates of the Bulgarian Exarchate schools in Macedonia, who had become teachers and inspectors in the same system that had educated them. Frustrated with the pace of change, they organized and networked to develop their movement throughout the Bulgarian school system that employed them. The Exarchate schools were an ideal forum in which to propagate their cause, and the leading members were able to circulate to different posts, to spread the word, and to build up supplies and stores for the anticipated uprising. As it became more powerful, IMRO was able to impress upon the Exarchate its wishes for teacher and inspector appointments in Macedonia. For more see: Julian Brooks, The Education Race for Macedonia, 1878—1903 in The Journal of Modern Hellenism, Vol 31 (2015) pp. 23-58.

- ^ Raymond Detrez Detrez, Raymond. The A to Z of Bulgaria, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 0810872021, p. 135.

- ^ IMRO group modeled itself after the revolutionary organization of Vasil Levski and other noted Bulgarian revolutionaries like Hristo Botev and Georgi Benkovski, each of whom was a leader during the earlier Bulgarian revolutionary movement. Duncan M. Perry, The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893-1903, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, pp. 39-40.

- ^ Jonathan Bousfield; Dan Richardson; Richard Watkins (2002). The Rough Guide to Bulgaria. Rough Guides. pp. 449–450. ISBN 1858288827. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "The French referred to 'Macedoine' as an area of mixed races — and named a salad after it. One doubts that Gotse Delchev approved of this descriptive, but trivial approach." Johnson, Wes. Balkan inferno: betrayal, war and intervention, 1990-2005, Enigma Books, 2007, ISBN 1929631634, p. 80.

- ^ "The Bulgarian historians, such as Veselin Angelov, Nikola Achkov and Kosta Tzarnushanov continue to publish their research backed with many primary sources to prove that the term 'Macedonian' when applied to Slavs has always meant only a regional identity of the Bulgarians." Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 112.

- ^ "Gotse Delchev, may, as Macedonian historians claim, have 'objectively' served the cause of Macedonian independence, but in his letters he called himself a Bulgarian. In other words it is not clear that the sense of Slavic Macedonian identity at the time of Delchev was in general developed." Moulakis, Athanasios. "The Controversial Ethnogenesis of Macedonia", European Political Science (2010) 9, ISSN 1680-4333. p. 497.

- ^ "Slavic Macedonian intellectuals felt loyalty to Macedonia as a region or territory without claiming any specifically Macedonian ethnicity. The primary aim of this Macedonian regionalism was a multi-ethnic alliance against the Ottoman rule." Ethnologia Balkanica, vol. 10–11, Association for Balkan Anthropology, Bŭlgarska akademiia na naukite, Universität München, Lit Verlag, Alexander Maxwell, 2006, p. 133.