Begging: Difference between revisions

WP Ludicer (talk | contribs) previous wording was fine |

No edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 189: | Line 189: | ||

===Romania=== |

===Romania=== |

||

Law 61 of 1991 forbids the persistent call for the mercy of the public, by a person who is able to work.<ref>{{ |

Law 61 of 1991<ref>{{Cite web |title=LEGE (A) 61 27/09/1991 - Portal Legislativ |url=https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/279788 |access-date=2024-05-30 |website=legislatie.just.ro}}</ref> forbids the persistent call for the mercy of the public, by a person who is able to work, although begging still remains widespread in the country.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Iorga |first=Mihai |date=2022-10-28 |title=E din nou plin de cerșetori pe străzi. Poliția Locală: Nu le mai dați bani! |url=https://stiridetimisoara.ro/e-din-nou-plin-de-cersetori-pe-strazi-politia-locala-nu-le-mai-dati-bani_46491.html |access-date=2024-05-30 |website=Stiri de Timisoara |language=ro-RO}}</ref> |

||

US State Department Human Rights reports note a pattern of [[Romani people|Roma]] children registered for "vagrancy and begging".<ref>{{cite web | publisher=U.S. Department of State | url=https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61641.htm | title=Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2005 (Romania) | date=2006-03-08 | author = Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor| access-date=2006-09-29 <!--DASHBot-->}}</ref> |

US State Department Human Rights reports note a pattern of [[Romani people|Roma]] children registered for "vagrancy and begging".<ref>{{cite web | publisher=U.S. Department of State | url=https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61641.htm | title=Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2005 (Romania) | date=2006-03-08 | author = Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor| access-date=2006-09-29 <!--DASHBot-->}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 05:04, 30 May 2024

Begging (also panhandling) is the practice of imploring others to grant a favor, often a gift of money, with little or no expectation of reciprocation. A person doing such is called a beggar or panhandler. Beggars may operate in public places such as transport routes, urban parks, and markets. Besides money, they may also ask for food, drink, cigarettes or other small items.

Internet begging is the modern practice of asking people to give money to others via the Internet, rather than in person. Internet begging may encompass requests for help meeting basic needs such as medical care and shelter, as well as requests for people to pay for vacations, school trips, and other things that the beggar wants but cannot comfortably afford.[1][2]

Beggars differ from religious mendicants in that some mendicants do not ask for money. Their subsistence is reciprocated by providing society with various forms of religious service, moral education, and preservation of culture.

History

Beggars have existed in human society since the dawn of recorded history. Street begging has happened in most societies around the world, though its prevalence and exact form vary.

Greece

Ancient Greeks distinguished between the pénēs (Greek: πένης, "active poor") and the ptōchós (Greek: πτωχός, "passive poor"). The pénēs was somebody with a job, only not enough to make a living, while the ptōchós depended on others entirely. The working poor were accorded a higher social status.[3] The New Testament contains several references to Jesus' status as the savior of the ptochos, usually translated as "the poor", considered the most wretched portion of society. In the Rich man and Lazarus parable, Lazarus is called 'ptochos' and presented as living in extreme poverty.

Great Britain

A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors, vulgarly called vagabonds, was first published in 1566 by Thomas Harman. From early modern England, another example is Robert Greene in his coney-catching pamphlets, the titles of which included "The Defence of Conny-catching," in which he argued there were worse crimes to be found among "reputable" people. The Beggar's Opera is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay. The Life and Adventures of Bampfylde Moore Carew was first published in 1745. There are similar writers for many European countries in the early modern period.[citation needed]

According to Jackson J. Spielvogel, "Poverty was a highly visible problem in the eighteenth century, both in cities and in the countryside... Beggars in Bologna were estimated at 25 percent of the population; in Mainz, figures indicate that 30 percent of the people were beggars or prostitutes... In France and Britain by the end of the century, an estimated 10 percent of the people depended on charity or begging for their food."[4]

The British Poor Laws, dating from the Renaissance, placed various restrictions on begging. At various times, begging was restricted to the disabled. This system developed into the workhouse, a state-operated institution where those unable to obtain other employment were forced to work in often grim conditions in exchange for a small amount of food. The welfare state of the 20th century greatly reduced the number of beggars by directly providing for the necessities of the poor from state funds.

India

Begging is an age-old social phenomenon in India. In the medieval and earlier times begging was considered to be an acceptable occupation which was embraced within the traditional social structure.[5] This system of begging and almsgiving to mendicants and the poor is still widely practiced in India, with over 500,000 beggars in 2015.[6]

In contemporary India, beggars are often stigmatized as undeserving. People often believe that beggars are not destitute and instead call them professional beggars.[vague][7][better source needed] There is a wide perception of begging scams.[8] This view is refuted by grassroots research organizations such as Aashray Adhikar Abhiyan, which claim that beggars and other homeless people are overwhelmingly destitute and vulnerable. Their studies indicate that 99 percent men and 97 percent women resort to beggary due to abject poverty, distress migration from rural villages and the unavailability of employment.[9]

China

Ming Dynasty

After the establishment of the Ming dynasty many farmers and unemployed laborers in Beijing were forced to beg to survive.[10] Begging was especially difficult during Ming times due to high taxes that limited the disposable income of most individuals.[11] Beijing's harsh winters were a difficult challenge for beggars. To avoid freezing to death, some beggars paid porters one copper coin to sleep in their warehouse for the night. Others turned to burying themselves in manure and eating arsenic to avoid the pain of the cold. Thousands of beggars died of poison and exposure to the elements every year.[10]

Begging was some people's primary occupation. A Qing dynasty source describes that "professional beggars" were not considered to be destitute, and as such were not allowed to receive government relief, such as food rations, clothing, and shelter.[12] Beggars would often perform or train animals to perform to earn coins from passerby.[11] Although beggars were of low status in Ming, they were considered to have higher social standing over prostitutes, entertainers, runners, and soldiers.[13]

Some individuals capitalized on beggars and became "Beggar Chiefs". Beggar chiefs provided security in the form of food for beggars and in return received a portion of beggars daily earnings as tribute. Beggar chiefs would often lend out their surplus income back to beggars and charge interest, furthering their subjects dependence on them to the point of near slavery. Although beggar chiefs could acquire significant wealth they were still looked upon as low class citizens. The title of beggar chief was often passed through family line and could stick with an individual through occupational changes.[13]

Religious begging

Many religions have prescribed begging as the only acceptable means of support for certain classes of adherents, including Hinduism, Sufism, Buddhism, Christianity, and typically to provide a way for certain adherents to focus exclusively on spiritual development without the possibility of becoming caught up in worldly affairs.

Religious ideals of ‘Bhiksha’ in Hinduism, ‘Charity’ in Christianity besides others promote almsgiving.[14] This obligation of making gifts to God by almsgiving explains the occurrence of generous donations outside religious sites like temples and mosques to mendicants begging in the name of God.

Tzedakah plays a central role in Judaism. The Jewish practice of maaser kesafim requires a contribution of 10% of one's income as a monetary tithe, mostly to be given to the poor.[15]

In Buddhism, monks and nuns traditionally live by begging for alms, as done by the historical Gautama Buddha himself. This is, among other reasons, so that Laity can gain religious merit by giving food, medicines, and other essential items to the monks. The monks seldom need to plead for food; in villages and towns throughout modern Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and other Buddhist countries, householders can often be found at dawn every morning streaming down the road to the local temple to give food to the monks. In East Asia, monks and nuns were expected to farm or work for returns to feed themselves.[16][17][18]

The biblical figure Jesus is said to have lived a simple life. He is said to have encouraged his disciples "to take nothing for their journey except a staff—no bread, no bag, no money in their belts—but to wear sandals and not put on two tunics."[19]

Ming China was founded by former beggar Zhu Yuanzhang. Orphaned in childhood due to famine, Zhu Yuanzhang, turned to the Huangjue temple for help. When the temple ran out of resources to support its occupants he became a mendicant monk traveling China begging for food.[20]

Legal restrictions

Begging has been restricted or prohibited at various times and for various reasons, typically revolving around a desire to preserve public order or to induce people to work rather than to beg. Various European Poor Laws prohibited or regulated begging from the Renaissance to modern times, with varying levels of effectiveness and enforcement. Similar laws were adopted by many developing countries.[citation needed]

"Aggressive panhandling" has been specifically prohibited by law in various jurisdictions in the United States and Canada, typically defined as persistent or intimidating begging.[21]

Afghanistan

Begging is banned in Afghanistan,[22] which mostly exists in Kabul, Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Australia

Each state and territory in Australia has specific laws regarding begging and panhandling. Begging for alms is illegal in Victoria, South Australia, Northern Territory, Queensland and Tasmania.[29][30]

Austria

There is no nationwide ban but it is illegal in several federal states.[31]

Belarus

It is legal to beg in Belarus.[32]

Belgium

Begging is legal in Belgium, but municipalities can restrict it.[33]

Brazil

It is legal to beg in Brazil, and receive medical care provided by law in SUS (Unique Health System)[34]

Bulgaria

Systematic begging is illegal in Bulgaria by article 329 of the penal code.[35]

Canada

The province of Ontario introduced its Safe Streets Act in 1999 to restrict specific kinds of begging, particularly certain narrowly defined cases of "aggressive" or abusive begging.[36] In 2001 this law was upheld under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[37] The law was further upheld by the Court of Appeal for Ontario in January 2007.[38]

One response to the anti-panhandling laws which were passed was the creation of the Ottawa Panhandlers Union which fights for the political rights of panhandlers. The union is a shop of the Industrial Workers of the World.[citation needed]

British Columbia enacted its own Safe Streets Act in 2004 which resembles the Ontario law. There are also critics in that province who oppose such laws.[39]

Chile

Begging in Chile has been decriminalized in the 1998.[40] Nevertheless, municipal governments from time to time attempt to reintroduce begging bans as city ordinances.

China

Begging in China is illegal if:

- Coercing, decoying or utilizing others to beg;

- Forcing others to beg, repeatedly tangling or using other means of nuisance.

Those cases are violations of the Article 41 of the Public Security Administration Punishment Law of the People's Republic of China. For the first case, offenders would receive a detention between 10 days and 15 days, with an additional fine under RMB 1,000; for the second case, it is punishable by a 5-day detention or warning.

According to Article 262(2) or the Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China, organizing disabled or children under 14 to beg is illegal and will be punished by up to 7 years in prison, and fined.[citation needed]

Denmark

Historically beggars were controlled by the Stodderkonge or 'beggar king' for a town or district. Today, begging in Denmark is illegal under section 197 of the penal code, which reads:

Whoever, despite a police warning, makes himself guilty of begging, or who allows someone under 18, who belongs to his household, to beg, is to be punished with prison up to 6 months. If there are extenuating circumstances, the punishment may be omitted. A warning in the context of this law is valid for 5 years.

- 2) The requirement for a warning does not apply when the act was taken on a pedestrian street, by a station, in or by a supermarket or in public transportation.

- 3) When determining punishment, it should be considered an aggravating circumstance if the act was taken in one of the places mentioned in 2).

[31][41] Furthermore, begging which causes insecurity in the streets (so-called utryghedsskabende tiggeri) has a harsher penalty of up to 14 days prison.[42]

England & Wales

Begging is illegal under the Vagrancy Act of 1824. However it does not carry a jail sentence and is not enforced in many cities,[43] although since the Act applies in all public places, it is enforced more frequently on public transport. Local authorities may issue public spaces protection orders for particular areas which makes begging subject to a fine.[44]

Finland

Begging has been legal in Finland since 1987 when the poor law was invalidated. In 2003, the Public Order Act replaced local government rules and decriminalized begging.[45]

France

A law against begging ended in 1994 but begging with aggressive animals or children is still outlawed.[31]

Greece

Under article 407 of the Greek Penal Code, begging was punishable by up to 6 months in jail and up to a 3000 euro fine. However, this law was repealed in October 2018, after protests from street musicians in the city of Thessaloniki.[46]

Hungary

Hungary has a nationwide ban. This may include stricter related laws in cities such as Budapest, which also prohibits picking things from rubbish bins.[31]

India

Begging is criminalized in cities such as Mumbai and Delhi as per the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, BPBA (1959).[47] Under this law, officials of the Social Welfare Department assisted by the police, conduct raids to pick up beggars who they then try in special courts called ‘beggar courts’. If convicted, they are sent to certified institutions called ‘beggar homes’ also known as ‘Sewa Kutir’ for a period ranging from one to ten years for detention, training and employment. The government of Delhi, besides criminalizing alms-seeking has also criminalized almsgiving on traffic signals to reduce the ‘nuisance’ of begging and ensure the smooth flow of traffic.

Aashray Adhikar Abhiyan and People's Union of Civil Liberties, PUCL have critiqued this Act and advocated for its repeal.[48] Section 2(1) of the BPBA broadly defines ‘beggars’ as those individuals who directly solicit alms as well as those who have no visible means of subsistence and are found wandering around as beggars. Therefore, during the implementation of this law the homeless are often mistaken as beggars.[9] Beggar homes, which are meant to provide vocational training, have been often found to have abysmal living conditions.[48]

In 2018, the Delhi High Court declared 25 provisions of Bombay Prevention of Begging Act (1959) as unconstitutional, following petitions filed by Harsh Mander and Karnika Sawhney.[49] In 2021, the Supreme Court refused to ban begging and observed that begging was a socioeconomic problem.[50]

Ireland

"Passive" begging is legal in Ireland, but begging "in an aggressive, intimidating or threatening manner" is illegal, punishable by a fine. Gardaí (police) can also direct people begging in certain areas to move on, e.g. at an ATM, night safe, vending machine or shop entrance.[51]

It is also illegal to "organise or direct someone else to beg;" under the Criminal Justice (Public Order) Act 2011, punishable by a €200,000 fine or up to 5 years in prison; this law was adopted in response to organised begging by Romani gangs.[52][53][54][55][56]

Prior to this law, begging was outlawed by the Vagrancy (Ireland) Act 1847, adopted during the Great Famine; a 2007 High Court ruling said that it was "too vague and incompatible with constitutional provisions allowing free speech and freedom to communicate."[57][58]

Italy

Begging with children or animals is forbidden, but the law is not enforced.[31]

Japan

Buddhist monks appear in public when begging for alms.[59] Although homelessness in Japan is common, such people rarely beg.[citation needed]

South Korea

Most cases of begging are illegal. Especially, if it annoys someone, or bothers the traffic, or is for a personal purpose.[citation needed]

Latvia

Begging was made illegal in the historic city center of Riga in 2012. Begging in Riga outside the historic city center requires that the beggar carries ID.[60]

Lithuania

It is illegal to beg in the capital Vilnius and it is also illegal to give money to a beggar. Both can receive a fine of up to 2000 litas (€770).[61]

Luxembourg

Begging in Luxembourg is legal, except when it is indulged in as a group or the beggar is a part of an organised effort. According to Chachipe, a Roma rights advocacy NGO, 1639 begging cases were reported by Luxembourgian law enforcement authorities. Roma beggars were arrested, handcuffed, taken to police stations and held for hours and had their money confiscated.[62]

Nepal

Although the Begging (Prohibition) Act was introduced in 1962,[63] this has not been enforced and the begging population in the capital, Kathmandu has since grown to over 5,000, according to police estimates.[64] Besides the common begging tricks such as asking for money or asking for milk which will be returned to the shop for money, there is a unique scam in Nepal which involves asking a foreigner to buy a shoe box at an inflated price. This shoe box is claimed to help provide a sustainable livelihood for the beggar but in fact, will be returned to the seller for money.[65]

Norway

Begging is banned in some counties and there were plans for a nationwide ban in 2015, however this was dropped after the Centre Party withdrew their support.[31]

Philippines

Begging is prohibited in the Philippines under the Anti-Mendicancy Law of 1978 although this is not strictly enforced.[66]

Poland

In Poland it is illegal to beg under the Code of petty offences, if they are able to hold a job or beg in public in a pressing or fraudulently (Article 58).[67] The beggar is due to a fine of €365.[68] Who tends to beg a minor or helpless person or dependant relative depending on him or dedicated under his custody, shall be punishable by detention, restriction of liberty or a fine (Article 104).

Portugal

In Portugal, panhandlers normally beg in front of Catholic churches, at traffic lights or on special places in Lisbon or Oporto downtowns. Begging is legal in Portugal. Many social and religious institutions support homeless people and panhandlers and the Portuguese Social Security normally gives them a survival monetary subsidy.[citation needed]

Qatar

Under the article 278 of the Qatari penal code, the maximum sentence for begging is one year. This sentence was increased from a maximum of three months before July 2006.[69] The alternative is housing in a specialized correctional facility. The money will be confiscated in any case.[70] This law is enforced, with a police division dedicated solely for that purpose.[71]

Romania

Law 61 of 1991[72] forbids the persistent call for the mercy of the public, by a person who is able to work, although begging still remains widespread in the country.[73]

US State Department Human Rights reports note a pattern of Roma children registered for "vagrancy and begging".[74]

United States

In parts of San Francisco, California, aggressive panhandling is prohibited.[75]

In May 2010, police in the city of Boston started cracking down on panhandling in the streets in downtown, and were conducting an educational outreach to residents advising them not to give to panhandlers. The Boston police distinguished active solicitation, or aggressive panhandling, versus passive panhandling of which an example is opening doors at a store with a cup in hand but saying nothing.[76]

U. S. Courts have repeatedly ruled that begging is protected by the First Amendment's free speech provisions. On August 14, 2013, the U. S. Court of Appeals struck down a Grand Rapids, Michigan, anti-begging law on free speech grounds.[77] An Arcata, California, law banning panhandling within twenty feet of stores was struck down on similar grounds in 2012.[78]

In Baltimore, Maryland, several non-profits have been working with the "squeegee kids" to get them off the streets instead of the police having to enforce the law and have the teens arrested.[79][80]

Use of funds

A 2002 study of 54 panhandlers in Toronto reported that of a median monthly income of $638 Canadian dollars (CAD) – those interviewed spent a median of $200 on food and $192 on alcohol, tobacco and illegal drugs.[81] The Fraser Institute criticized this study, citing problems with potential exclusion of lucrative forms of begging and the unreliability of reports from the panhandlers who were polled in the study.[82]

In North America, panhandling money is widely reported to support substance abuse and other addictions. For example, outreach workers in downtown Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, surveyed that city's panhandling community and determined that approximately three-quarters use some of the donated money to buy tobacco products, while two-thirds buy solvents[vague] or alcohol.[83]

Vouchers

Because of concerns that people begging on the street may use the money to support alcohol or drug abuse, some advise those wishing to give to beggars to give gift cards or vouchers for food or services, and not cash.[83][84][85][86][87][88] Some shelters also offer business cards with information on the shelter's location and services, which can be given in lieu of cash.[89]

In fine art

There are many depictions of beggars in fine art.[90]

-

The Singing Beggars by Russian painter Ivan Yermenyov c. 1775

-

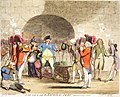

In a 1786 James Gillray caricature, the plentiful money bags handed to King George III are contrasted with the beggar whose legs and arms were amputated, in the left corner

-

Portrait of a Blind Beggar, Glamorganshire, George Orleans Delamotte, 1818

-

Beggar family at the road, by Robert Wilhelm Ekman, 1860

-

"The Man with the Twisted Lip", illustrated by Sidney Paget 1891, a beggar playing a major role in a Sherlock Holmes adventure.

-

Louis Dewis, "The Old Beggar", Bordeaux, France, 1916

Notable beggars

- Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, accepted alms from people to survive[91]

- Bampfylde Moore Carew, the self-styled "King of the Beggars"

- So Chan, a Chinese folk hero of Drunken Fist

- Diogenes of Sinope, a Greek philosopher

- Dobri Dobrev, a Bulgarian ascetic and philanthropist

- Gallicina, the mendicant Darotti is accused of murdering in Susan Palwick's novel, The Necessary Beggar (2005)

- Nicholas Jennings, characterized as a rogue, in Thomas Harman's A Caveat for Common Cursitors

- Jesus, the founder of Christianity, despised materialism and encouraged an ascetic life[92][93][94]

- Lazarus, a Biblical character described in the Gospel of Luke, in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (also called the Dives and Lazarus or Lazarus and Dives)

- "The Man with the Twisted Lip", the titular character of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's eponymous Sherlock Holmes short story

- Gavroche Thenardier, a fictional character in Victor Hugo's novel Les Misérables

- Wu Xun, was a Chinese wandering beggar and educational reformer

- Zhu Yuanzhang, the founder of the Ming Dynasty

See also

References

- ^ "GoFundMe CEO: One-Third of Site's Donations Are to Cover Medical Costs". Time. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- ^ McClanahan, Carolyn. "People Are Raising $650 Million On GoFundMe Each Year To Attack Rising Healthcare Costs". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- ^ Cavallo, Guglielmo (1997). The Byzantines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-226-09792-3.

- ^ Jackson J. Spielvogel (2008). "Western Civilization: Since 1500". Cengage Learning. p.566. ISBN 0-495-50287-1

- ^ Pande, B.B (1983). "The Administration of Beggary Prevention Laws in India: a legal aid viewpoint". 11. International Journal of the Sociology of Law: 291–304.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Over 5 Lakh Beggars in India, West Bengal Tops the List Among States".

- ^ "6 Professional Beggars In India Who Are Probably Richer Than You & I". 2015-07-25.

- ^ "India Beggars and Begging Scams: What You Should Know". Archived from the original on 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ a b AAA, Ashray Adhikar Abhiyan (2006). People Without A Nation: the destituted people; A documented outcome of the national consultation on Urban Poor: Special Focus on Beggary and Vagrancy Laws- the issue of De-custodialisation (De-criminalization). Print-O-Graph, New Delhi. p. 8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Cass, Victoria (1999). Dangerous Women: Warriors, Grannies, and Geishas of the Ming. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 7. ISBN 0-8476-9395-3.

- ^ a b Powers, Martin (2019). China and England: The Preindustrial Struggle for Justice in Word and Image. New York: Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 978-1138504035.

- ^ Liu-Hung, Huang (1984). A Complete Book Concerning Happiness and Benevolence: A Manual for Local Magistrates in Seventeenth-Century China. Translated by Djang, Chu. Arizona: The University of Arizona Press. p. 554. ISBN 0-8165-0820-8.

- ^ a b Feng, Menglong (2000). Feng. Translated by Shuhui, Yang; Yunqin, Yang. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 478–480. ISBN 0-295-97843-0.

- ^ Gopalakrishnan, A. (2002). "Poverty As Crime". Frontline Magazine. 19: 23.

- ^ "Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De'ah 249". www.sefaria.org.

- ^ "農禪vs商禪" (in Chinese). Blog.udn.com. 2009-08-19. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ "僧俗". 2007.tibetmagazine.net. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ "鐵鞋踏破心無礙 濁汗成泥意志堅 – 記山東博山正覺寺仁達法師". Hkbuddhist.org. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ "Mark 6:8 | English Standard Version :: ERF Bibleserver".

- ^ Hung, Hing Ming (2016). From the Mongols to the Ming Dynasty : How a Begging Monk Became Emperor of China, Zhu Yuan Zhang. New York: Algora Publishing. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1628941524.

- ^ Johnson, Johnny (November 3, 2008). "In tough times, panhandling may increase in Oklahoma City". The Oklahoman.

- ^ "'I Have No Choice': Cleared From The Streets, Kabul's Poorest Go Door-To-Door In Search Of Alms". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. February 23, 2023. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Authorities Begin Campaign to Round Up Beggars in Balkh". TOLOnews. April 7, 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- ^ "In Herat, population of beggars surges by 30pc". Pajhwok Afghan News. August 23, 2022. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Gathering Beggers from Streets Reach Almost 30,000 in Kabul". Bakhtar News Agency. March 6, 2023. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Kabul rounds up over 28,000 beggars". Ariana News. February 14, 2023. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Women make most of the rounded up beggars". Pajhwok Afghan News. September 22, 2022. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Committee Formed to Provide Aid to Those Begging on Kabul Streets: Baradar". TOLOnews. August 13, 2022. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ Nightingale, Tom (2016-10-18). "Welfare organisations call for begging to be decriminalised". ABC News. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- ^ "Summary Offences Act 1953 – Sect. 12". South Australian Government. Archived from the original on 2020-04-16. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ^ a b c d e f "(swedish) I Haag stoppade man tiggarna med förbud". Sveriges Television.

- ^ "As Economy Reels, Belarusian Beggars Face Cold Shoulder From Authorities". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "58 bedelaars moeten geld afgeven in Antwerpen". VRT NWS. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ "Agora é lei: Morador de rua deve ser atendido pelo SUS".

- ^ https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/bg/bg024en.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Safe Streets Act". Government of Ontario. 1999. Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- ^ "'Squeegee kids' law upheld in Ontario". CBC News. 2001-08-03. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- ^ "Squeegee panhandling washed out by Ontario Appeal Court". CBC News. 2007-01-17. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ "Police chief welcomes Safe Streets Act". CBC News. 2004-10-26. Archived from the original on 2007-05-10. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- ^ "Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional | Ley Chile".

- ^ "Straffeloven kap. 22" (in Danish). Archived from the original on 2014-11-09. Retrieved 2014-11-09.

- ^ "Vedtaget: Nu skal hjemløse 14 dage i fængsel for at tigge". TV2. 14 June 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Bunyan, Nigel (2003-08-22). "Beggar ban may spark nationwide crackdown". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ "Huge increase in Public Spaces Protection Order fines". BBC News. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ "Authorities powerless to act against beggars with children in tow". Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ "Καταργείται το άρθρο 407 του Ποινικού Κώδικα για την επαιτεία" (in Greek). 2018-10-30.

- ^ "The Bombay Prevention of Begging Act" (PDF). 1959.

- ^ a b "Criminalizing Poverty". Archived from the original on 2016-10-12.

- ^ Singh, Soibam Rocky (2018-08-08). "Delhi High Court decriminalises begging in the national capital". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "'Can't ban begging': SC issues notice to Centre, Delhi government for beggars' COVID vaccination". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "Public order offences". www.citizensinformation.ie.

- ^ "Roma begging gangs broken up". herald.

- ^ MacNamee, Garreth (15 March 2017). "'It's only getting worse': Up to 80 beggars on Dublin's city streets at any one time". TheJournal.ie.

- ^ "Gangs of beggars suspected of being trafficked into Ireland". IrishCentral.com. December 26, 2017.

- ^ "Judge hits out at 'gang of professional beggars' who fly in and out of Romania in shifts". 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Ireland's big street begging scam". IrishCentral.com. March 29, 2019.

- ^ "Begging crackdown law comes into force". independent. 2 February 2011.

- ^ Carolan, Mary. "Court challenge to begging law succeeds". The Irish Times.

- ^ "The Zen – Teaching of Mu". Japan National Tourist Organisation. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ^ "Begging in downtown Riga banned". The Baltic Times. 2012-08-01. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Lithuania Cracks Down On Beggars And Almsgivers". Salon. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Groth, Annette (2012-06-01). "The situation of Roma in Europe: movement and migration" (PDF). Council of Europe: Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ "Nepal – Begging (Prohibition) Act, 1962". ilo.org. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ "Beggar population swells as anti-begging Act gathers dust". kathmandupost.ekantipur.com. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ "21 Tourist targeted scams in Nepal". Travelscams.org. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Borromeo, Rene (16 December 2013). "Should you give to beggars? Cebu City's Anti-Mendicancy Campaign" (in Cebuano and English). Cebu: The Freeman. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Act Of 20 May 1971 The Code Of Offences

- ^ . Housing RIghts Watch https://www.housingrightswatch.org/sites/default/files/2012-12-11_RPT_POLAND_anti_soc_laws_en.pdf. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Al-Meezan 2".

- ^ "Al Meezan".

- ^ "Al-Arab News 1".

- ^ "LEGE (A) 61 27/09/1991 - Portal Legislativ". legislatie.just.ro. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ Iorga, Mihai (2022-10-28). "E din nou plin de cerșetori pe străzi. Poliția Locală: Nu le mai dați bani!". Stiri de Timisoara (in Romanian). Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2006-03-08). "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2005 (Romania)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Debate Continues Over Proposed Sit-Lie Ordinance Archived 2010-12-02 at the Wayback Machine, KTVU, 10 March 2010

- ^ Schuler, Melina, "Cops Planning to Combat Panhandling", The Boston Courant, May 14–20 issue, 2010. "Aggressive solicitation is against the law and is defined as an action that is likely to cause a reasonable person to fear harm or to intimidate him or her into compliance, Ivens said. Passive panhandling, like in front of a convenience store, is constitutionally allowed, however, it is a violation of a Boston ordinance to do it within 10 feet [3 m] of an ATM, bank, or check cashing business during hours of operation, [Boston Police Captain Paul] Ivens said."

- ^ John Agar, "Michigan's begging law violates First Amendment: federal appeals court" mlive.com

- ^ Romney, Lee (September 27, 2012). "Arcata panhandling law mostly struck down by judge: A Humboldt County judge says provisions of the ordinance banning non-aggressive panhandling within 20 feet of stores, intersections, parking lots and bus stops are unconstitutional". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ "Squeegee collaborative working to better the lives of youth squeegee workers". www.wmar2news.com. 27 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "A better way for Baltimore to help its 'squeegee kids'". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Bose, Rohit & Hwang, Stephen W. (2002-09-03). "Income and spending patterns among panhandlers". Canadian Medical Association Journal. Vol. 167, no. 5. pp. 477–479. PMC 121964.

- ^ "Begging for Data". Canstats. 3 September 2002. Archived from the original on 20 April 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- ^ a b "'Change for the Better' fact sheet" (PDF). Downtown Winnipeg Biz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- ^ Wahlstedt, Eero. "Evaluation study of the Oxford Begging Initiative". Oxford City Council. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Johnsen & Fitzpatrick, S. & S. (2010). "Revanchist Sanitisation or Coercive Care? The Use of Enforcement to Combat Begging, Street Drinking and Rough Sleeping in England". Urban Studies. 47 (8): 1703–1723. Bibcode:2010UrbSt..47.1703J. doi:10.1177/0042098009356128. S2CID 154772918.

- ^ Hermer, J. (1999). Policing compassion: 'Diverted Giving' on the Winchester High Street. Bristol: The Policy Press. ISBN 978-1861341556. Archived from the original on October 25, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ "Real Change, not Spare Change". Portland Business Alliance. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ^ Dromi, Shai M. (2012). "Penny for your Thoughts: Beggars and the Exercise of Morality in Daily Life". Sociological Forum. 27 (4): 847–871. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01359.x.

- ^ Peace Studies Program. "Homelessness Contact Cards". George Washington University. Archived from the original on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ^ Disability in Art History

- ^ "Begging Bowl - Buddhist Things". ReligionFacts. Archived from the original on 2011-12-05. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ Marshall, I. Howard (2002-04-16). "Jesus outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence by Robert E. Van Voorst (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000. xiv = 248 pp. pb. $22.00/£12.99. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9)". Evangelical Quarterly. 74 (2): 191–192. doi:10.1163/27725472-07402014. ISSN 0014-3367.

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. pp. 65-66.

- ^ "Mark 6:8 | English Standard Version :: ERF Bibleserver". www.bibleserver.com. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

Further reading

- Malanga, Steven, The Professional Panhandling Plague Archived 2008-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, City Journal, vol. 18, no. 3, Summer 2008, The Manhattan Institute, New York, NY.

- Narkewicz, David J. (October 2019). "A Downtown Northampton for Everyone: Residents, Visitors, Merchants, and People At-Risk: Mayor's Work Group on Panhandling Study Report". Northampton, Massachusetts, US. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2019-12-24. A detailed report by a city in Western Massachusetts, US.

- Sandage, Scott A., Born Losers: A History of Failure in America, Harvard University Press, 2005

External links

- Rooney, Emily, "Panhandling—Public Nuisance or Basic Right?", The Emily Rooney Show, WGBH-FM Radio, Boston, Tuesday, June 5, 2012. Guests: Vincent Flanagan, Executive Director of Homeless Empowerment Project Spare Change News; Robert Haas, Cambridge Police Commissioner; Denise Jillson, President of the Harvard Square Business Association

- Selected legal cases on panhandling in the United States, University of Albany Center for Problem Oriented Policing.