Iberian Union: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

eliminate duplicate sentence |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

To unite Iberia was one of the ambitions of medieval monarchs of the Iberian peninsula. [[Sancho III of Navarre]] and [[Alfonso VII of Castile]] both took the title ''[[Emperor|Imperator]] Totius [[Hispania|Hispaniae]]'', meaning "[[Imperator totius Hispaniae|Emperor of All Spains]]"<ref>Notice that, before the emergence of the modern country of Spain (beginning with the union of [[Crown of Castile|Castile]] and [[Aragon]] in [[1492]]), the [[Latin]] word ''[[Hispania]]'', in any of the [[Iberian Romance languages]], either in singular or plural forms (in English: Spain or Spains), was used to refer to the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, and not exclusively, as in modern usage, to the country of [[Spain]], thus excluding [[Portugal]].</ref> centuries before. The union could have been achieved earlier had [[Miguel da Paz]], [[Prince of Asturias]], become king. He died early in his childhood. |

To unite Iberia was one of the ambitions of medieval monarchs of the Iberian peninsula. [[Sancho III of Navarre]] and [[Alfonso VII of Castile]] both took the title ''[[Emperor|Imperator]] Totius [[Hispania|Hispaniae]]'', meaning "[[Imperator totius Hispaniae|Emperor of All Spains]]"<ref>Notice that, before the emergence of the modern country of Spain (beginning with the union of [[Crown of Castile|Castile]] and [[Aragon]] in [[1492]]), the [[Latin]] word ''[[Hispania]]'', in any of the [[Iberian Romance languages]], either in singular or plural forms (in English: Spain or Spains), was used to refer to the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, and not exclusively, as in modern usage, to the country of [[Spain]], thus excluding [[Portugal]].</ref> centuries before. The union could have been achieved earlier had [[Miguel da Paz]], [[Prince of Asturias]], become king. He died early in his childhood. |

||

The history of Portugal from the dynastic crisis in 1578 to the first [[Braganza Dynasty]] monarchs is a period of transition. The [[Portuguese Empire]] was near its height at the start of this period and continued to enjoy widespread influence in the world after [[Vasco da Gama]] had finally achieved the goal that emerged from the exploratory efforts inaugurated by [[Henry the Navigator]] of reaching the east by sailing around Africa in [[1497]]-[[1498]], thereby opening up an oceanic route for the immensely profitable [[spice trade|spice trade]] into Europe that bypassed the [[Middle East]]. |

|||

Throughout the [[17th century]] the increasing predations and surrounding of Portuguese trading posts in the east, by the Dutch, English and French, and their rapidly growing intrusion into the the [[Atlantic slave trade]], undermined Portugals' near monopoly on the lucrative oceanic spice and slave trades, thereby sending the kingdom into a long decline. To a lesser extent the diversion of wealth from Portugal by the Habsburg regime to help support the Catholic side of the [[Thirty Years War]] and in fighting the [[Eighty Years' War|Dutch]], also contributed to the weakening of [[Portugal]]'s financial position. However it should be noted that Spain's checking of rival powers extended the period of Iberian maritime dominance, albeit under severe challenge, well into the 17th century. These events, and those which occurred at the end of [[House of Aviz|Aviz dynasty]] and the period of [[Iberian Union]], led Portugal to a state of dependency on its colonies, first [[India]] and then Brazil. This shift from India to Brazil was a consequence of the rise of the [[Dutch Empire|Dutch]] and [[British Empire|British]] empires that grew from their trading posts in the east. A similar shift occurred after the independence of Brazil, resulting in Portugal focusing more on its possessions in [[Africa]]. |

Throughout the [[17th century]] the increasing predations and surrounding of Portuguese trading posts in the east, by the Dutch, English and French, and their rapidly growing intrusion into the the [[Atlantic slave trade]], undermined Portugals' near monopoly on the lucrative oceanic spice and slave trades, thereby sending the kingdom into a long decline. To a lesser extent the diversion of wealth from Portugal by the Habsburg regime to help support the Catholic side of the [[Thirty Years War]] and in fighting the [[Eighty Years' War|Dutch]], also contributed to the weakening of [[Portugal]]'s financial position. However it should be noted that Spain's checking of rival powers extended the period of Iberian maritime dominance, albeit under severe challenge, well into the 17th century. These events, and those which occurred at the end of [[House of Aviz|Aviz dynasty]] and the period of [[Iberian Union]], led Portugal to a state of dependency on its colonies, first [[India]] and then Brazil. This shift from India to Brazil was a consequence of the rise of the [[Dutch Empire|Dutch]] and [[British Empire|British]] empires that grew from their trading posts in the east. A similar shift occurred after the independence of Brazil, resulting in Portugal focusing more on its possessions in [[Africa]]. |

||

Revision as of 03:37, 27 May 2007

| History of Portugal |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| History of Spain |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

Iberian Union is modern day term that refers to the historical political unit that governed all of the Iberian peninsula south of the Pyrenees from 1580-1640.

This union was composed of Portugal and Spain, after the Portuguese dynastic crisis and in a personal union of the crowns, along with their respective colonial possessions.

To unite Iberia was one of the ambitions of medieval monarchs of the Iberian peninsula. Sancho III of Navarre and Alfonso VII of Castile both took the title Imperator Totius Hispaniae, meaning "Emperor of All Spains"[1] centuries before. The union could have been achieved earlier had Miguel da Paz, Prince of Asturias, become king. He died early in his childhood.

The history of Portugal from the dynastic crisis in 1578 to the first Braganza Dynasty monarchs is a period of transition. The Portuguese Empire was near its height at the start of this period and continued to enjoy widespread influence in the world after Vasco da Gama had finally achieved the goal that emerged from the exploratory efforts inaugurated by Henry the Navigator of reaching the east by sailing around Africa in 1497-1498, thereby opening up an oceanic route for the immensely profitable spice trade into Europe that bypassed the Middle East.

Throughout the 17th century the increasing predations and surrounding of Portuguese trading posts in the east, by the Dutch, English and French, and their rapidly growing intrusion into the the Atlantic slave trade, undermined Portugals' near monopoly on the lucrative oceanic spice and slave trades, thereby sending the kingdom into a long decline. To a lesser extent the diversion of wealth from Portugal by the Habsburg regime to help support the Catholic side of the Thirty Years War and in fighting the Dutch, also contributed to the weakening of Portugal's financial position. However it should be noted that Spain's checking of rival powers extended the period of Iberian maritime dominance, albeit under severe challenge, well into the 17th century. These events, and those which occurred at the end of Aviz dynasty and the period of Iberian Union, led Portugal to a state of dependency on its colonies, first India and then Brazil. This shift from India to Brazil was a consequence of the rise of the Dutch and British empires that grew from their trading posts in the east. A similar shift occurred after the independence of Brazil, resulting in Portugal focusing more on its possessions in Africa.

Establishment of the Iberian Union

The Battle of Alcazarquivir in 1578 saw both the death of the young king Sebastian and the end of the House of Aviz. Sebastian's successor, the Cardinal Henry of Portugal, was 70 years old at the time. Henry's death was followed by a dynastical crisis, with three grandchildren of Manuel I claiming the throne: Catherine, Duchess of Braganza, married to John, 6th Duke of Braganza, António, Prior of Crato and Philip II of Spain. António had been acclaimed King of Portugal by the people of Santarém on July 24, 1580 and then in many cities and towns throughout the country. Some members of the Council of Governors of Portugal, who had supported Philip, escaped to Spain and declared him to be the legal successor of Henry. Then, Philip II marched into Portugal and defeated the troops loyal to the Prior of Crato in the Battle of Alcântara. Philip II was crowned Philip I of Portugal in 1581 (recognized as official king by the Cortes of Tomar) and the Portuguese House of Habsburg (also called the Philippine Dynasty) began.

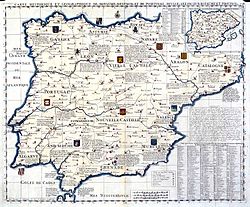

Red/Pink - Spanish Empire

Blue/Light Blue - Portuguese Empire

(Areas explored & claimed by the Spanish, but unsettled, (ie: Amazon basin) not shown.)

Portugal's status was maintained under the first two kings of the Iberian Union, Philip I and his son Philip II of Portugal and III of Spain. Both monarchs gave excellent positions to Portuguese nobles in the Spanish courts, and Portugal maintained an independent law, currency, and government. It was even proposed to move the Royal capital to Lisbon. However, the joining of the two crowns deprived Portugal of a separate foreign policy, and Spain's enemies became Portugal's. The war with England led to a deterioration of the relations with Portugal's oldest ally (since the Treaty of Windsor in 1386) and the loss of Hormuz, although the English hope in an rebellion against the kings (tried by Elisabeth I) assured the survival of the alliance. War with the Dutch led to invasions of many countries in Asia, including Ceylon (today's Sri Lanka), and commercial interests in Japan, Africa (Mina), and South America. Even though Portuguese were unable to capture the entire island of Ceylon, they were able to keep the coastal regions of Ceylon under their control for a considerable time. Brazil was partially conquered by both France and the Seventeen Provinces. The Dutch intrusion into Brazil was longer lasting and more troublesome to Portugal. The Seventeen Provinces captured a large portion of the Brazilian coast including Bahia, Salvador, Recife, Pernambuco, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará, and Sergipe, while Dutch privateers sacked Portuguese ships in both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The large area of Bahia and its city, Salvador, was recovered quickly by a Portuguese-Spanish military expedition in 1625. The other smaller, less developed areas were recovered in stages and relieved of Dutch piracy in the next two of decades by local resistance and Portuguese expeditions.

The End of the Union

When Philip II died, he was succeeded by Philip III (and IV of Spain) who had a different approach on Portuguese issues. Taxes raised affected mainly the Portuguese merchants (Carmo Reis 1987). Portuguese nobility began to lose its importance at the Spanish Cortes, and government posts in Portugal were occupied by Spaniards. Ultimately, Philip III tried to make Portugal a royally-governed province and Portuguese nobles lost all of their power.

This situation culminated in a revolution by the nobility and high bourgeoisie on December 1 1640, 60 years after the crowning of Philip I. The plot was planned by Antão Vaz de Almada, Miguel de Almeida and João Pinto Ribeiro. They, together with several associates, killed Secretary of State Miguel de Vasconcelos and imprisoned the king's cousin, the Duchess of Mantua, who had governed Portugal in his name. The moment was well chosen, as Philip's troops were at the time fighting the Thirty Years' War and also facing a revolution in Catalonia.

The support of the people became apparent almost immediately and soon John, 8th Duke of Braganza, was acclaimed King of Portugal throughout the country as John IV. By December 2 1640, John was already sending a letter as sovereign of the country to the Municipal Chamber of Évora.

War with Spain and recovery of the colonies

The subsequent Portuguese Restoration War against Philip III (Portuguese: Guerra da Restauração) consisted mainly of small skirmishes near the border. The most significant battles being the Battle of Montijo on May 26 1644, the Battle of the Lines of Elvas (1659), the Battle of Ameixial (1663), the Battle of Castelo Rodrigo (1664), and the Battle of Montes Claros (1665); the troops of John IV were victorious in all of these battles.

The victories were made possible because John IV made several decisions in order to strengthen the his forces. On December 11 1640, the Council of War was created to organize all the operations (Mattoso Vol. VIII 1993). Next, the king created the Junta of the Frontiers, to take care of the fortresses near the border, the hypothetical defense of Lisbon, and the garrisons and sea ports. In December 1641, a tenancy was created to assure upgrades on all fortresses that would be paid with regional taxes. John IV also organized the army establishing the Military Laws of King Sebastian and developed an intense diplomatic activity restoring good relations with England.

After gaining several decisive victories, John quickly tried to make peace. His demand that Philip recognized the new ruling dynasty in Portugal was not fulfilled until the reign of his son Afonso VI during the regency of Peter of Braganza (another son of John and future King Peter II of Portugal).

John IV to John V

The Portuguese Royal House of Braganza began with John IV. The Dukes of the House of Braganza were a branch of the House of Aviz created by Afonso V for his half-uncle Afonso, Count of Barcelos, illegitimate son of John I, first monarch of the House of Aviz. The Braganzas soon became one of the most powerful families of the kingdom and for the next decades would inter-marry many Portuguese royal family members. In 1565, John, 6th Duke of Braganza married Princess Catherine, granddaughter of King Manuel I. This connection with the Royal Family proved determinant in the rise of the House of Braganza to a Royal House. Catherine was one of the strongest claimants of the throne during the dynastical crisis of 1580 but lost the struggle to her cousin Philip II of Spain. Eventually Catherine's grandson became John IV of Portugal as he was held to be the legitimate heir.

John IV was a beloved monarch, a patron of fine art and music, and a proficient composer and writer on musical subjects. He collected one of the largest libraries in the world (Madeira & Aguiar, 2003). Among his writings is a defense of Palestrina and a Defense of Modern Music (Lisbon, 1649). Abroad, the Dutch took Malacca (January 1641) and the Sultan of Oman captured Muscat (1648). By 1654, however, most of Brazil was back in Portuguese hands and had effectively ceased to be a viable Dutch colony. John married his daughter Catherine of Braganza to Charles II of England, offering Tangiers and Bombay as a dowry. John IV died in 1656 and was succeeded by his son Afonso VI.

|

Notes

- ^ Notice that, before the emergence of the modern country of Spain (beginning with the union of Castile and Aragon in 1492), the Latin word Hispania, in any of the Iberian Romance languages, either in singular or plural forms (in English: Spain or Spains), was used to refer to the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, and not exclusively, as in modern usage, to the country of Spain, thus excluding Portugal.