Anti-intellectualism: Difference between revisions

revert POV (and ironic bad spelling, considering the article!) |

|||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

Both O'Reilly and Limbaugh, as well as other conservative hosts such as [[Tucker Carlson]] and [[Joe Scarborough]] are frequently accused of having anti-intellectual atmospheres on their shows, evidenced by their frequent interruption of guests who try to put forward complex arguments. Scarborough once commented that, "If my guest is allowed to speak uninterrupted for more than 15 seconds, then I'm not doing my job." |

Both O'Reilly and Limbaugh, as well as other conservative hosts such as [[Tucker Carlson]] and [[Joe Scarborough]] are frequently accused of having anti-intellectual atmospheres on their shows, evidenced by their frequent interruption of guests who try to put forward complex arguments. Scarborough once commented that, "If my guest is allowed to speak uninterrupted for more than 15 seconds, then I'm not doing my job." |

||

=====Sensationalism===== |

=====[[Sensationalism]]===== |

||

Some analysts feel the lack of intellectual content is representative of the media's propensity, in the service of higher [[ratings]], to promote argument and spectacle rather than informed debate. Among those analysts, scholars such as [[Noam Chomsky]] believe that this [[soundbite]] atmosphere of the media inherently promotes pro-[[establishment]] views and aids in the [[Manufacturing Consent|manufacture of consent]]. |

Some analysts feel the lack of intellectual content is representative of the media's propensity, in the service of higher [[ratings]], to promote argument and spectacle rather than informed debate. Among those analysts, scholars such as [[Noam Chomsky]] believe that this [[soundbite]] atmosphere of the media inherently promotes pro-[[establishment]] views and aids in the [[Manufacturing Consent|manufacture of consent]]. |

||

Revision as of 00:05, 12 December 2007

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. |

Anti-intellectualism describes a sentiment of hostility towards, or mistrust of, intellectuals and intellectual pursuits. This may be expressed in various ways, such as attacks on the merits of science, education, or literature.

Anti-intellectuals often perceive themselves as champions of the ordinary people and egalitarianism against elitism, especially academic elitism. These critics argue that highly educated people form an isolated social group that tends to dominate political discourse and higher education (academia).

Anti-intellectualism can also be used as a term to criticize an educational system if it seems to place minimal emphasis on academic and intellectual accomplishment, or if a government has a tendency to formulate policies without consulting academic and scholarly study.

Expression

Anti-intellectualism will often be expressed within communities through declarations of Otherness, that is, intellectuals will be said to be 'not one of us'. Those who mistrust intellectuals will represent them as a danger to normality, insisting that they are outsiders with little empathy for the common people. This has historically resulted in intellectuals being painted as arrogant members of a different social grouping. In rural communities, for example, intellectuals may be viewed as "city slickers" who know little of the country and its ways. It is also common for communities to typecast intellectuals as foreigners or members of ethnic minorities. Along with this, intellectuals will often be said to be prone to mental instability, their critics insisting there is a medically proven connection between genius and madness. Communities where religious faith is strong may endeavor to link intellectuals with the promotion of atheism, while the sexual mores of intellectuals can be also placed in doubt in some cultures where they can be suspected of high promiscuity, bisexual or homosexual tendencies. Notably, those who disapprove of intellectuals often view them as exhibiting not one, but a combination of these character traits.

Causes

Anti-intellectual beliefs may come from a variety of sources. These include:

Religion

Although a variety of religions have rich intellectual traditions, some rely on arguments from authority that are not independently verifiable, along with a somewhat common tendency to reject secular critical traditions.

It is more common for fundamentalist wings of a religion to harbor anti-intellectual sentiments, due to a tendency to reject that which runs contrary to their religious beliefs. However, it is important to note that this is not necessarily the case with all religious groups, and that many religious groups pride themselves on their scholarly, as well as religious, traditions.

When religious doctrines include statements about natural or human history, the provenance of sacred texts (and other matters), such claims may be investigated by external scholarship. For example a claim about the age of a religious artifact may be scientifically tested, or a theodicy may be logically examined. If such an investigation is instigated, the outcome may therefore create conflict in relation to how an adherent to the doctrine perceives it as confirming or denying that their belief.

However, religious anti-intellectualism is not confined to hostility against science: When movements such as bohemianism, avant-gardism and romanticism become major factors in the fine arts, religious believers may perceive these trends to be subversive of morality and call for censorship. This has been a fairly common theme in socio-cultural trends in the Americas and Europe since the time of the Reformation. Some would argue, however, that this is just moral conservatism, which is distinct from anti-intellectualism, though the two positions are allied in many cases.

Authoritarian politics

Anti-intellectualism is often used by dictators or those seeking to establish dictatorships. Educated people as a social group have often been seen by totalitarian elements as a threat because of the tendency of intellectuals to question existing social norms and to dissent from established opinion. Thus, often violent anti-intellectual backlashes are common during the rise and rule of authoritarian political movements, such as Fascism, Stalinism and Theocratic rule. Moreover, because many intellectuals refuse to embrace nationalism, they are also commonly portrayed as unpatriotic and subversive.

The most extreme dictatorships, such as that of the Khmer Rouge, simply murdered anyone with more than a rudimentary education. Other expressions of anti-intellectualism range from the closure of public libraries and places of learning through to official declarations that intellectuals are prone to mental illness and enacting laws to have them placed under supposed psychiatric care. In addition, intellectuals in countries ruled by authoritarian governments are often subject to popular condemnation and used as scapegoats to divert the anger of the public away from those in power. Anti-intellectualism is not necessarily violent, however, and not necessarily oppressive. Anti-intellectual attitudes can be held by any group, including non-violent ones, as well as by individuals who merely disfavor intellectualism and learning in general. According to Jorge Majfud, "this contempt that arises from a power installed in the social institutions and from the inferiority complex of its actors, is not a property of 'underdeveloped' countries. In fact, it is always the critical intellectuals, writers or artists who head the top-ten lists of the most stupid of the stupid in the country." [1]

Populism

Populism can be another major strain of anti-intellectualism. In this context, intellectuals are presented as elitists and tricksters whose knowledge and rhetorical skills are feared, not because they are useless, but because they may be used to hoodwink the ordinary people, who are conceived of as the 'salt of the earth' and the source of virtue. American President George W. Bush has been accused of appealing to this type of populism. [1] Those who argue from populist ideals will often assert that knowledge needs to be regulated by the people, claiming that educators need to work in line with policies made by stakeholders such as parent groups.

In a similar vein, the curiosity and objectivity of intellectuals about foreign countries and beliefs is portrayed as a lack of patriotism or moral clarity, and intellectuals are often held to be suspect of holding dangerously foreign, possibly subversive, opinions. An extreme form was embodied by Joseph McCarthy, the fanatically anti-Communist senator from Wisconsin.

Issues within the educational system

The educational system may serve as a powerful tool for forming the culture of a nation. In the English speaking world, particularly in the United States and United Kingdom, the schools and universities have often been criticized for being overtaken by overtly 'Intellectualist' trends and hence not preparing the youth properly to be members of society who would be cultured, prepared for challenging jobs, and capable of independent thought.

In primary and secondary schools

Some commentators[2] believe that primary and secondary schools, at least in the United States, place too much emphasis on equality of outcome at the expense of individual intellectual achievement. In the view of such commentators, such emphasis leads to a Handicapper General mentality and the dumbing down of the curriculum.

The demands of youth culture

A major preserve of real, though hardly militant or even self-aware, anti-intellectualism in the contemporary world is a youth subculture often associated with those students who are more interested in social life or athletics than in their studies. Such subcultures, often marked by cliques, exist among students of all groups. Commercial youth culture also generates a dizzying variety of fads. Keeping up with the trends is difficult, and their content is frequently criticised by cultural critics of many different persuasions for being simple-minded and pandering to unsophisticated appetites. Pursuing popularity has been likened by blog writer Paul Graham to a full time job that leaves little time for intellectual interests. [2]

The Frontline Special "Merchants of Cool(2/27/2001)" (script) suggests that advertising giants are creating an anti-intellectual, commodity-obsessed generation.

In the current of anti-intellectualism among African American and Hispanic youth is the perception that focusing on school studies means "acting white". Authors associated with criticism of this view include John McWhorter, whose book Losing the Race: Self-Sabotage in Black America (Harper, 2001, ISBN 0-06-093593-6) collects narratives and criticizes the cultivation of "ebonics" as an alternative speech norm, specifically labelling this as an instance of anti-intellectualism. Conservative commentators Thomas Sowell and Dinesh D'Souza are also associated with criticism of this view. Henry Louis Gates cited an informal poll in which African-American students in the Washington, DC area were asked what constituted "acting white"; according to Gates "the top three things were: making straight A's, speaking standard English and going to the Smithsonian". [3] A study conducted by Roland G. Fryer indicated that in public schools, popularity among African-Americans and Hispanics declined as GPA increased, while among white students popularity increased with GPA. [4] While Fryer's study indicates that anti-intellectualism is far less prevalent among white students, it doubtless does occur, especially among children of the underclass and the leisure class. [citation needed]

In colleges

In the realm of higher education concerns are generally threefold:

Political bias

One type of criticism is based upon the perception that university professors and other academics have increasingly inculcated their own political ideologies into pedagogical interactions and professional research at the cost of the quality, objectivity, and appropriateness of each. This claim is more often made by those individuals on the conservative side of the American political spectrum against political liberals, as understood in a contemporary sense of the term as well as radicals and leftists. Whether this focus on the proverbial "ivory tower left" is deserved is, rather unsurprisingly, the subject of much intense debate both within the Academy and various political spheres.

Generally, these criticisms are brought up against persons working within the field of the Humanities-especially a set of the Humanities falling under the large subdivision of the Social Sciences. Among the fields most contested are Women's Studies, Cultural Studies, Ethnic Studies or Racial Studies. Whether such field-specific attention is deserved is, once again, the subject of much intense debate.

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. |

When the criticism of political bias is set in the context of American liberals vs. American conservatives, as it often is, the dialogue between the two sides can become rapidly polemical. One finds conservative critics called "anti-intellectuals" as they attempt to bring the charge of political bias against various liberals even as the accused liberals are charged with such things as "re-writing history" (Historical revisionism); the validity of each party's assertion must be recognized to vary from case to case.

Deficient programs

Another major concern centers on the perceived lack of general education in college curricula. Critics claim[who?] , for example, that college students ought to take more humanities classes, such as history or literature, along with the requirements of their major. Allegedly, there is also a deficiency of academic rigor in the university liberal arts programs that are available to students, stemming from the aforementioned political bias, which is said to lead professors to concentrate on trendy and controversial subjects to the neglect of what is considered legitimate art and literature.

Notably, the humanities requirements in American colleges are actually much greater than in many other countries, such as Russia or India where college instruction is focused almost entirely on professional, often technical, preparation. It may be argued that in these countries it is generally believed high school education has given a student sufficient exposure to general education topics.

Lack of usefulness

A third line of criticism, sometimes seeming to contradict the second, is the absence of 'real life' usefulness from the study of humanities. This has also contributed to anti-intellectualism, particularly among those who study, or have studied, technical subjects. This is sometimes considered more of a 'rival-intellectualism' rather than true anti-intellectualism, inasmuch as people who have received university-level technical training have themselves engaged in an intellectual activity of great complexity.

Anti-intellectualism in the United States

19th Century culture

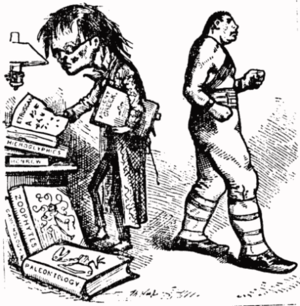

19th century popular culture is important in the history of American anti-intellectualism. At the time when the vast majority of the population led a rural life, full of manual labor and agriculture, bookish education, which at the time focused on classics, was seen to have little value. It should be noted that Americans of the era were generally very literate and, in fact, read Shakespeare much more than their present-day counterparts. However, the ideal at the time was an individual skilled and successful in his trade and a productive member of society; studies of classics and Latin in colleges were generally derided.

The 19th century predominantly valued the self-reliant and "self-made man," schooled by society and by experience, over the intellectual whose learning was acquired through books and formal study. In 1843, Bayard R. Hall wrote of frontier Indiana, that "(w)e always preferred an ignorant bad man to a talented one, and hence attempts were usually made to ruin the moral character of a smart candidate; since unhappily smartness and wickedness were supposed to be generally coupled, and incompetence and goodness." Still, there was a possibility for redemption if the "egghead" embraced common mores. A character of O. Henry noted that once a graduate of an East Coast college gets over being vain, he makes just as good a cowboy as any other young man.

The related stereotype of the slow-witted naïf with a heart of gold, which became popular in 19th century stage shows, still reappears in American culture, recently in the 1985 novel and 1994 motion picture Forrest Gump.

20th and 21st century culture

Right-wing currents

Conservative critiques of academia

William F. Buckley, Jr. once remarked that he'd rather be governed by the first hundred names in the Boston phone book than by the faculty of Harvard University, and many other conservatives have displayed similar disdain for academia. Institutions such as Harvard, Princeton, Yale, and various other prestigious colleges have been portrayed on the right as centers of a radical and anti-American leftism.

Robert Warshow has put forth the hypothesis that the Communist Party became central to American intellectual life during the 1930s:

- For most American intellectuals, the Communist movement of the 1930s was a crucial experience. In Europe, where the movement was at once more serious and more popular, it was still only one current in intellectual life; the Communists could never completely set the tone of thinking. . . . But in this country there was a time when virtually all intellectual vitality was derived in one way or another from the Communist party. If you were not somewhere within the party’s wide orbit, then you were likely to be in the opposition, which meant that much of your thought and energy had to be devoted to maintaining yourself in opposition.[5]

A more recent variant on this tendency is the so-called "academic freedom" movement, led by David Horowitz and his Center for the Study of Popular Culture, which claims the identity politics and left-wing views of certain academics are a means of indoctrinating university students with anti-American views [6]. Some even go so far as to say the work of these left-wing professors provides encouragement and ideological ammunition for America's enemies (and might cite, for example, the apparent influence of Noam Chomsky on Hugo Chavez as suggested by the latter's endorsement of Hegemony or Survival before the United Nations).[citation needed]

Religious fundamentalism

Much modern American anti-intellectualism originates from the commonly held view among conservative Christians that the current form of public education subverts religious belief. The validity of this view, in fact, was well substantiated by the spread of atheism and Deism among the educated during the Enlightenment, and was deep-rooted even before that time. Hence, for instance, the New England writer and Puritan John Cotton wrote in 1642, "The more learned and witty you bee, the more fit to act for Satan will you bee." More recently, an anti-intellectual current is claimed by some in the works of Fundamentalist Christian cartoonist Jack Chick. In his anti-evolution tract Big Daddy? for example, he depicts the academic establishment as intolerant and elitist in their rejection of young earth creationism. [7]

Some Christians, while not considering education an inherent evil, object to what they perceived as "un-Christian" elements, especially in public schools (K-12) and colleges and universities. Focal points for fundamentalist criticism are comprehensive sex education and evolution.

Left-wing currents

1960s student culture

Especially in the 1960s many student demonstrators romanticized the impoverished populations of Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta. The lack of formal education in these regions was seen as a sort of freedom from "conformist" society that allowed one to lead a more genuine and worthy life. The sanitized version of folk music that became popular on campus around this time is a related trend.

The anti-war movement also despised the highly educated and objective Washington technocrat, epitomized by Robert McNamara, who was not moved by subjective, irrational emotions. McNamara was alleged to make decisions solely on numbers and probabilities and could not see individual lives or deaths as anything but statistics. The Vietnam body count was offered as an example of this objectivity.

Theodor Adorno, himself a Marxist, sharply criticised this trend in the 60's Left, which he called "actionism," defined as the belief that actions such as protests and strikes could change the political structure by themselves without being supported by solid theory and an organized program or party.

Also, some of the extremes of the student movement at the time were heavily influenced by Maoism, which has a strong anti-intellectual component.

The intellectual as paid apologist for the status quo

Many on the left have claimed that the intellectual's status as a "professional thinker" requires the support of a member of the ruling class willing to fund them.[citation needed] Therefore, most intellectuals, in order to maintain their profession, must assume a subservient posture towards the current power structure even when their ideas are outwardly "radical." These critics point out that many a tenured professor has called for revolution, but few have ever taken concrete steps to promote one. This has the effect of discrediting the idea of social change by associating it with hypocritical academics, thereby serving the status quo.

In return for their rhetorical services, so this theory goes, intellectuals are rewarded with the power to set themselves up as the social betters of the proletariat and are given a measure of control over how normal people live their lives. In addition, when government actions go awry, intellectuals provide rulers with a convenient scapegoat - those who were paid to promote the policy can easily be blamed for creating it.

Although not a leftist thinker, Eric Hoffer is closely associated with this view of intellectuals. He compared them to the scribes that directed the construction of the pyramids - seemingly authoritative figures, who were in reality servants to the Pharaoh.

Economic factors

Although the factual evidence is at best dubious, many Americans believe that in the past five to ten years once-plentiful high-tech and skilled technical jobs have begun to disappear from America, and have been replaced with low-wage service occupations which at most require a high school diploma.[citation needed] Therefore the economic incentive to attend college, where one might be exposed to intellectual ideas and garner an appreciation for them, has lessened. There thus exists the potential for increased anti-intellectualism in the future. However, statistics indicate that currently in the United States half the adult population has at least some college experience and one-third of that population are graduates.

In American political discourse

The United States of America, more than other developed nations, has been accused of suffering from anti-intellectualism, particularly by the intellectuals in both the United States and Europe. Such accusations are particularly fueled by the political schism between the Republican and Democratic parties. The less scrupulous contenders on both sides use the accusation of anti-intellectualism as a rhetorical weapon, but most often it is Democrats that accuse Republican backers of exploiting public sentiments against the values of the intellectuals for Republicans' own economic gain.

Many Democrats and liberals claim that conservative beliefs about foreign affairs or economics stem from "ignorance," poor education, and a "lack of awareness" of the substantive issues involved, and as such are anti-intellectual. The liberal position often contends that conservative ideology has a tendency to approach issues such as morality and foreign policy in "simplistic" ways, breaking them down into easily understood confrontations between good and evil. The left views its own ideology as more sophisticated and worldly, and based on an interpretative study of human history.[citation needed]

In the media

In the US 2000 Presidential Election, the media (particularly late night comics) portrayed Candidate Al Gore as a boring "brainiac" who spoke in a monotonous voice and jabbered on about numbers and figures that no one could understand. His supposed "claim to have invented the Internet"[8] was widely ridiculed. It was the classic stereotype of a pompous, out-of-touch intellectual, and this perception arguably hurt Gore in the election. In the years since, debate between the left and right in America has often centered on the relation of the intellectual class to the public as a whole.

Conservative commentators such as Ann Coulter, Bill O'Reilly, and Rush Limbaugh commonly argue that conservative politicians, particularly Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, have been attacked by media as being "incompetent" - this can be understood as an accusation of intellectual snobbery by the media. O'Reilly in particular is well known for having a hostile attitude towards what he calls the "Ivy League Elite." The word "intellectual" itself has been used as an insult by many on the right.

Both O'Reilly and Limbaugh, as well as other conservative hosts such as Tucker Carlson and Joe Scarborough are frequently accused of having anti-intellectual atmospheres on their shows, evidenced by their frequent interruption of guests who try to put forward complex arguments. Scarborough once commented that, "If my guest is allowed to speak uninterrupted for more than 15 seconds, then I'm not doing my job."

Some analysts feel the lack of intellectual content is representative of the media's propensity, in the service of higher ratings, to promote argument and spectacle rather than informed debate. Among those analysts, scholars such as Noam Chomsky believe that this soundbite atmosphere of the media inherently promotes pro-establishment views and aids in the manufacture of consent.

There is a strong feeling on both sides of the political divide that corporate news focuses too much on soundbites and headlines, and not enough on in-depth reporting. Researchers have noticed a trend in the amount of coverage newspapers and broadcast networks devote to various subjects: World events and political coverage are receiving a declining percentage of print space and airtime, while crimes, sex scandals, and celebrity intrigue take up more and more space.[citation needed]. See also: Junk food news.

This trend is clearly visible on cable television as well. For example, The Discovery Channel and The Learning Channel have shifted from airing purely documentary and informational content to devoting a large portion of their programming to makeover specials, home-remodeling shows, and programs focused on muscle cars and motorcycles.[citation needed]. See also: Criticisms of Oprah Winfrey.

Anti-intellectualism in the Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union, within the first decade after the Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks generally scorned and suspected the educated as potential traitors to the cause of the proletariat. Whereas the core of the Communist Party was well-educated, the people who became local activists and officials in government and industry often lacked at least formal education and disdained those who had it. Lenin once called the intelligentsia, particularly those who opposed him, "rotten" and "shit".[citation needed] The boast, roughly translated as "we ain't completed no academies" ("мы академиев не кончали") became a byword for the new ruling elite.[citation needed]

Later on, the Soviet government came to see education as important and dedicated great resources to literacy on the one hand, and higher and professional education on the other. However, as a matter of social policy, the government sought to promote the working class over an intellectual elite. Accordingly, industrial workers often received greater salaries than university-trained professionals such as teachers, doctors, and engineers. Moreover, workers were covertly inculcated with the notion that only the manual labor creates real value in the economy, whereas the educated people just sit around writing papers.[citation needed]

It must be stressed, however, that the anti-intellectualism of the Soviet political elite was closely associated with the fact that the Russian academic milieu, as a part of the tzarist state apparatus, had been hostile to the 1917 Bolshevik takeover almost by definition; however, when dealing with practical issues such as economic and scientific management, the early Soviet regime had to resort to such "bourgeois experts", therefore the tense relationship between the Communist Party elite and non-Party educated people. It was only during the early 1930s that Stalin attempted to replace the old intelligentsia with a new, Party-approved group. Such favouring of partinost - that is to say, a partisan stance towards all matters intellectual - over formal scholarship, no matter how crude such partisan stance happened to be - in the end amounted to a clear anti-intellectual stance.

The Soviet treatment of science is an example of anti-intellectualism - the triumph of Lysenkoism in Soviet Russia was a result of political bullying of scientists and the punishment of dissenters rather than the normal scientific process of publishing one's findings.

Anti-intellectualism in Asia - China, Cambodia and Iran

Asian anti-intellectualism has deep roots. Even the Tao Te Ching advises rulers to keep their subjects with a "full belly and an empty mind" and that "ignorance is better than knowledge" among the people.

A number of Asian countries have experienced degrees of anti-intellectualism in the 20th century.

In Cambodia, a country where few people have access to formal education (the literacy rate is about 50% as of 2004), the Khmer Rouge regime (1975–1979) was generally disdainful of intellectuals and saw many as enemies or traitors (see also: Democratic Kampuchea). In some sectors, anyone who wore glasses was shot by Khmer guards, as glasses were seen as a mark of education and intellectualism.

The revolutionary regime in the newly established Islamic Republic of Iran also displayed a streak of anti-intellectualism in its policies. Besides the emigration of many well-educated, western-trained, intellectuals in the wake of the revolution, the government decreed in 1980 that all universities are to be closed until the curricula are "purified" from the corrupt Pahlavi legacy. The ban on secular high education persisted until 1982. Also, the repressive attitude of the regime toward Iranian intelligentsia is well known (a highly publicized case of intellectual repression was the execution of the poet Said Soltanpour in 1981). It should be noted, however, that the revolutionary reforms in high education in Iran did democratize it somewhat, opening it to wider straits of population, who couldn't afford it beforehand (40% of all seats in the universities were reserved for Iran-Iraq war veterans) or were taken aback by the extremely westernized attitude of Iranian university circles under the Pahlavis.

Anti-intellectualism in the classical world

The Roman statesman Cato the Elder's public career displayed many traits that today would be considered anti-intellectual. He vehemently opposed the introduction of Greek cultural ideals and models into the Roman republic, believing them to be subversive of traditional plainspokenness and rugged military values. He urged the Roman Senate to pass its decree against the newly imported Bacchanalian mysteries, which it did in the Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus in 186 BC. He urged the deportation of three Athenian philosophers, Carneades, Diogenes the Stoic, and Critolaus, who had been sent to Rome as ambassadors from Athens, on the grounds that he believed the opinions they expressed were dangerous. The Emperor Augustus also exiled many philosophers.

However, rulers in the ancient and classical worlds were generally intolerant of anyone who disagreed with them. Anti-intellectualism as hostility by self-identified "common" people, or those that claim to speak for them, against a perceived class of cultural elites is generally considered a modern phenomenon.

See also

- Anti-science

- Atheists in foxholes

- Appeal to emotion

- Boffin

- Burning of books and burying of scholars

- Creation-evolution controversy

- Cultural Cringe (Colonial Anti-Intellectualism)

- Frugality

- God complex

- Handicapper General (primarily associated with U.S. anti-intellectualism)

- Infidels

- Keeping up with the Joneses

- Lysenkoism

- Obscurantism

- Philistinism

- Pop philosophy

- Populism

- Propaganda

- Tall Poppy Syndrome (Australian anti-intellectualism)

- The Professors: The 101 Most Dangerous Academics in America

- Truthiness

- Dumbing down

References

- ^ Baker, Peter; "The President as Average Joe: Trying to Boost Support, Bush Brings Banter to the People"; washingtonpost.com; April 2, 2006.

- ^ John Tierney, "When Every Child Is Good Enough," The New York Times, November 21, 2004

- Anti-intellectualism in American Life, by Richard Hofstadter: ISBN 0-394-70317-0

- Anti-Intellectualism in American Media, by Dane S. Claussen: New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-8204-5721-3

- Evening Chats in Beijing: Probing China's Predicament, by Perry Link: New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991. ISBN 0393310655

- Hinton, William. Hundred Day War: The Cultural Revolution at Tsinghua University. New York: New York UP, 1972. ISBN 0-85345-281-4.

- Moynihan Commission Report, Appendix A, 7. The Cold War, footnote 103 quoted from Robert Warshow, The Legacy of the 30’s: Middle-Class Mass Culture and the Intellectuals’ Problem, Commentary Magazine (December 1947): 538.

- "Action Will be Taken" Left Anti-Intelectualism and its Discontents by Liza Featherstone, Doug Henwood, and Christian Parenti (Left Business Observer)