Little Ice Age: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Rv to WMC: please don't try to assert that this is IPCC POV, its not, its the refs therein. Remove "still-to-glob": this is implicit in the less-clear. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The '''Little Ice Age''' (LIA) was a period of cooling lasting approximately from the mid-[[14th century|14th]] to the mid-[[19th century|19th]] centuries. This cooling brought an end to an unusually warm era known as the [[Medieval climate optimum]]. There were three maxima, beginning about [[1650]], about [[1770]], and [[1850]], each separated by slight warming intervals [http://eobglossary.gsfc.nasa.gov/Library/glossary.php3?xref=Little%20Ice%20Age]. |

The '''Little Ice Age''' (LIA) was a period of cooling lasting approximately from the mid-[[14th century|14th]] to the mid-[[19th century|19th]] centuries. This cooling brought an end to an unusually warm era known as the [[Medieval climate optimum]]. There were three maxima, beginning about [[1650]], about [[1770]], and [[1850]], each separated by slight warming intervals [http://eobglossary.gsfc.nasa.gov/Library/glossary.php3?xref=Little%20Ice%20Age]. |

||

It was initially believed that the LIA was a global phenomenon; |

It was initially believed that the LIA was a global phenomenon; it is now less clear that this is true. See [[Medieval climate optimum]] for more on this. |

||

The [http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/070.htm IPCC], based on Bradley and Jones, 1993; Hughes and Diaz, 1994; Crowley and Lowery, 2000 describes the LIA as ''a modest cooling of the Northern Hemisphere during this period of less than 1°C'', and says ''current evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this timeframe, and the conventional terms of "Little Ice Age" and "Medieval Warm Period" appear to have limited utility in describing trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries''. |

The [http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/070.htm IPCC], based on Bradley and Jones, 1993; Hughes and Diaz, 1994; Crowley and Lowery, 2000 describes the LIA as ''a modest cooling of the Northern Hemisphere during this period of less than 1°C'', and says ''current evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this timeframe, and the conventional terms of "Little Ice Age" and "Medieval Warm Period" appear to have limited utility in describing trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries''. |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

* [http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/paleo/pubs/hendy2002/hendy2002.html Abrupt Decrease in Tropical Pacific Sea Surface Salinity at End of Little Ice Age ] ("indicates that sea surface temperature and salinity were higher in the 18th century than in the 20th century") |

* [http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/paleo/pubs/hendy2002/hendy2002.html Abrupt Decrease in Tropical Pacific Sea Surface Salinity at End of Little Ice Age ] ("indicates that sea surface temperature and salinity were higher in the 18th century than in the 20th century") |

||

* [http://members.lycos.nl/ErrenWijlens/co2/cycles.htm Dansgaard cycles and the Little Ice Age (LIA) ] (it is not easy to see a LIA in the graphs) |

* [http://members.lycos.nl/ErrenWijlens/co2/cycles.htm Dansgaard cycles and the Little Ice Age (LIA) ] (it is not easy to see a LIA in the graphs) |

||

* [http://www.enn.com/news/enn-stories/2000/03/03012000/core_10591.asp Little ice age holds big climate clues ] |

|||

* [http://www-user.zfn.uni-bremen.de/~gheiss/Personal/Abstracts/SAJS2000_Abstr.html The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warming in South Africa ] |

* [http://www-user.zfn.uni-bremen.de/~gheiss/Personal/Abstracts/SAJS2000_Abstr.html The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warming in South Africa ] |

||

* [http://calspace.ucsd.edu/virtualmuseum/climatechange2/04_3.shtml The Riddle of the Little Ice Age ] |

* [http://calspace.ucsd.edu/virtualmuseum/climatechange2/04_3.shtml The Riddle of the Little Ice Age ] |

||

Revision as of 13:45, 18 July 2005

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of cooling lasting approximately from the mid-14th to the mid-19th centuries. This cooling brought an end to an unusually warm era known as the Medieval climate optimum. There were three maxima, beginning about 1650, about 1770, and 1850, each separated by slight warming intervals [1].

It was initially believed that the LIA was a global phenomenon; it is now less clear that this is true. See Medieval climate optimum for more on this.

The IPCC, based on Bradley and Jones, 1993; Hughes and Diaz, 1994; Crowley and Lowery, 2000 describes the LIA as a modest cooling of the Northern Hemisphere during this period of less than 1°C, and says current evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this timeframe, and the conventional terms of "Little Ice Age" and "Medieval Warm Period" appear to have limited utility in describing trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries.

Northern Hemisphere

The Little Ice Age brought bitterly cold winters to many parts of the world, but is most thoroughly documented in Europe and North America. In the mid-17th century, glaciers in the Swiss Alps advanced, gradually engulfing farms and crushing entire villages. The River Thames and the canals and rivers of the Netherlands often froze over during the winter, and people skated and even held frost fairs on the ice. In the winter of 1780, New York Harbor froze, allowing people to walk from Manhattan to Staten Island. Sea ice surrounding Iceland extended for miles in every direction, closing that island's harbors to shipping. The Arctic pack ice extended so far south that there are six records of Eskimos landing their kayaks in Scotland [2].

The severe winters affected human life in ways large and small. The population of Iceland fell by half, and the Viking colonies in Greenland died out. In North America, Native Americans formed leagues in response to food shortages [3].

In many years, snowfall was much heavier than recorded before or since, and the snow lay on the ground for many months longer than it does today. Many springs and summers were outstandingly cold and wet, although there was great variability between years and groups of years. Crop practices throughout Europe had to be altered to adapt to the shortened, less reliable growing season, and there were many years of dearth and famine. Violent storms caused massive flooding and loss of life. Some of these resulted in permanent losses of large tracts of land from the Danish, German, and Dutch coasts [4].

The extent of mountain glaciers had been mapped by the late 1800s. In both the north and the south temperate zones of our planet, snowlines (the boundaries separating zones of net accumulation from those of net ablation) were about 100 m lower than they were in 1975 [5]. In Glacier National Park, the last episode of glacier advance came in the late 18th and early 19th century [6]. In Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, large temperature excursions during the Little Ice Age (~1400-1900 AD) and the Medieval Warm Period (~800-1300 AD) possibly related to changes in the strength of North Atlantic thermohaline circulation [7].

In Ethiopia and Mauritania, permanent snow was reported on mountain peaks at levels where it does not occur today. Timbuktu, an important city on the trans-Saharan caravan route, was flooded at least 13 times by the Niger River; there are no records of similar flooding before or since. In China, warm weather crops, such as oranges, were abandoned in Kiangsi Province, where they had been grown for centuries. In North America, the early European settlers also reported exceptionally severe winters. For example, in 1607-8 ice persisted on Lake Superior until June [8].

The Little Ice Age can be seen in the art of the time; for example, snow dominates many village-scapes by the Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Younger, who lived from 1564 to 1638.

Another famous person to live during the LIA was Antonio Stradivari, a violin maker. The colder climates of the time caused the wood from the trees he used to be denser; the superb tone of Stradivari's creations has been partially attributed to this.

Depictions of winter in European painting

Burroughs (Weather, 1981) analyses the depiction of winter in paintings. He notes that these occurred almost entirely from 1565 to 1665, and was associated with the climatic decline from 1550 onwards. He notes that prior to this there are almost no depictions of winter in art, and hypothesises that the unusually harsh winter of 1565 insipired great artists to depict highly original images, and the decline in such paintings was a combination of the "theme" having been fully explored, and mild winters interrupting the flow of painting.

The famous winter paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (e.g. Hunters in the Snow) appear to all have been painted in 1565. Burroughs states that Pieter Brueghel the Younger "slavishly copied his fathers designs. The derivative nature of so much of this work makes it difficult to draw any definite conclusions about the influence of the winters between 1570 and 1600...". Dutch painting of the theme appears to begin with Avercamp after the winter of 1608. There is then an interruption of the theme between 1627 and 1640, with a sudden return thereafter; this hints at a milder interlude in the 1630's. The 1640's to the 1660's covers the major period of Dutch winter painting, which fits with the known proportion of cold winters then.

The final decline in winter painting, around 1660, does not coincide with an amelioration of the climate; Burroughs therefore cautions against trying to read too much into artisitic output, since fashion plays a part. He notes that winter painting recurs around 1780's and 1810's, which again marked a colder period.

Southern Hemisphere

An ice core from the eastern Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula clearly identifies events of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period [9]. These events cover approximately the last 300 years, ie 1700 onwards, and show non-cold conditions applying during much of the period conventionally labelled "little ice age", including the time of the "frost fair" type pictures shown above. This illustrates the non-globality of the LIA.

Ice cores from the Upper Fremont Glacier in North America and the Quelccaya Ice Cap (Peruvian Andes, South America) show similar changes during the LIA [10].

The Siple Dome has a climate event with an onset time that is coincident with that of the LIA in the North Atlantic based on a correlation with the GISP2 record. This event is the most dramatic climate event seen in the SD Holocene glaciochemical record [11]. Siple Dome ice core also contained its highest rate of melt layers (up to 8%) between 300 and 450 years ago, most likely due to warm summers. [12]

Law Dome ice cores show lower levels of CO2 mixing ratios during 1550-1800 A.D., probably as a result of colder global climate [13].

Sediment cores (Gebra-1 and Gebra-2) in Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula, have neoglacial indicators by diatom and sea-ice taxa variations during the period of the LIA [14].

Tropical Pacific coral records indicate the most frequent, intense ENSO activity occurred in the mid-17th century, during the Little Ice Age [15].

Climate patterns

In the North Atlantic, sediments accumulated since the end of the last ice age nearly 12,000 years ago show regular increases in the amount of coarse sediment grains deposited from icebergs melting in the now open ocean, indicating a series of 1-2ºC (2-4°F) cooling events recurring every 1,500 years or so. The most recent of these cooling events was the Little Ice Age. These same cooling events are detected in sediments accumulating off Africa, but the cooling events appear to be larger, ranging between 3-8ºC (6-14°F) [16].

Causes

Scientists have identified two causes of the Little Ice Age from outside the ocean/atmosphere/land systems: decreased solar activity and increased volcanic activity. Research is ongoing on more ambiguous influences such as internal variability of the climate system, and anthropogenic influence (Ruddiman). Some have also speculated that depopulation of Europe during the Black Death, and the resulting decrease in agricultural output, may have prolonged the Little Ice Age.

Solar activity

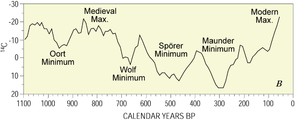

During the period 1645–1715, right in the middle of the Little Ice Age, solar activity as seen in sunspots was extremely low, with some years having no sunspots at all. This period of low sunspot activity is known as the Maunder Minimum. The precise link between low sunspot activity and cooling temperatures has not been established. But the coincidence of the Maunder Minimum with the deepest trough of the Little Ice Age is suggestive of such a connection [17]. Other indicators of low solar activity during this period are levels of carbon-14 and beryllium-10 [18].

Volcanic activity

Throughout the Little Ice Age the world also experienced heightened volcanic activity. When a volcano erupts, its ash reaches high into the atmosphere and can spread to cover the whole earth. This ash cloud blocks out some of the incoming solar radiation, leading to world-wide cooling that can last up to two years after an eruption. Also emitted by eruptions is sulfur in the form of SO2 gas. When this gas reaches the stratosphere it turns into sulfuric acid particles, which reflect the sun's rays, further reducing the amount of radiation reaching the earth's surface. The 1815 eruption of Tambora in Indonesia blanketed the atmosphere with ash; the following year, 1816, came to be known as the Year Without A Summer, when frost and snow were reported in June and July in both New England and Northern Europe.

End of Little Ice Age

Beginning around 1850, the world's climate began warming again and the Little Ice Age may be said to have come to an end at that time. Some scientists believe that the Earth's climate is still recovering from the Little Ice Age and that this situation contributes to concerns over human-caused climate change.

See also

External links

- Little Ice Age a global event and Annotated Bibliography

- IPCC on Was there a Little Ice Age and a Medieval Warm Period?

- Huascaran (Peru) Ice Core Data from the NOAA/NGDC Paleoclimatology Program

- Abrupt Decrease in Tropical Pacific Sea Surface Salinity at End of Little Ice Age ("indicates that sea surface temperature and salinity were higher in the 18th century than in the 20th century")

- Dansgaard cycles and the Little Ice Age (LIA) (it is not easy to see a LIA in the graphs)

- Little ice age holds big climate clues

- The Little Ice Age and Medieval Warming in South Africa

- The Riddle of the Little Ice Age

- What the Little Ice Age reveals about the South American monsoon system, and vice versa.

- Was El Niño unaffected by the Little Ice Age?

- Evidence for the Little Ice Age in Spain

- On LIA