Millennium '73: Difference between revisions

prominently featured = featured, and other tweaks. |

→World Peace Corps: teddy bears? (This has been fixed before.) |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

The World Peace Corps (WPC), headed by Maharaj Ji's 19-year-old youngest brother, Raja Ji, was the DLM's security force at the event. He said its job was "to make sure that whatever is happening, happens correctly."<ref name="And It Is Divine 1973"/> The WPC members at the festival were reported to be mostly English followers.<ref name ="Goldsmith 1974"/> One of the WPC's main jobs was keeping followers away from their guru.<ref name="Levine 1974"/><ref>{{Harvnb|Rudin|Rudin|1980|p=67}}</ref> |

The World Peace Corps (WPC), headed by Maharaj Ji's 19-year-old youngest brother, Raja Ji, was the DLM's security force at the event. He said its job was "to make sure that whatever is happening, happens correctly."<ref name="And It Is Divine 1973"/> The WPC members at the festival were reported to be mostly English followers.<ref name ="Goldsmith 1974"/> One of the WPC's main jobs was keeping followers away from their guru.<ref name="Levine 1974"/><ref>{{Harvnb|Rudin|Rudin|1980|p=67}}</ref> |

||

The World Peace Corps' name was called [[doublespeak]] and compared to the [[Big Lie]].<ref name="Scheer 1974"/><ref name ="Goldsmith 1974"/> They were seen by one reporter as "threatening, cajoling and generally pushing everyone around",<ref name="Kelley February 1974"/> by another as "a Guru goon squad of tough-looking teddy |

The World Peace Corps' name was called [[doublespeak]] and compared to the [[Big Lie]].<ref name="Scheer 1974"/><ref name ="Goldsmith 1974"/> They were seen by one reporter as "threatening, cajoling and generally pushing everyone around",<ref name="Kelley February 1974"/> by another as "a Guru goon squad of tough-looking teddy boy types from Britain",<ref name ="Dreyer 1974"/> and by a member as a "corps of sweet-looking ushers and more brawny strongarms."<ref name="Collier 1978 p=188">{{harvnb|Collier|1978| p=188}}</ref> Described as dour and brutal,<ref name="Gray 1973"/><ref>{{Harvnb|Kelley|1974b|p= 150}}</ref> they were seen by one reporter as exemplifying "the inevitable violence of any millennial sect hell-bent on abstract purity and infinite happiness."<ref name="Gray 1973"/> One observer was quoted as saying, "These people were mad with a sense of divinity-authorized power. It was like descending into the ninth ring of hell."<ref>{{Harvnb|Kelley|1974b|p=150}}</ref> |

||

===''And It Is Divine'' special issue=== |

===''And It Is Divine'' special issue=== |

||

Revision as of 15:40, 30 December 2008

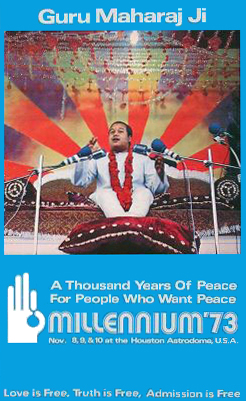

Millennium '73 was a free three-day festival held at the Houston, Texas, Astrodome in November 1973 by the Divine Light Mission (DLM). It featured Prem Rawat, then better known as Guru Maharaj Ji, who was then a 15-year-old guru and the leader of one of the fastest-growing religious movements in the West.[1] The festival was billed as ushering in "a thousand years of peace for people who want peace,"[2][3] and the dawn of a New Age.[4]

According to the official schedule, the three evening addresses by Guru Maharaj Ji were the main events.[5] The rest of the festival's program comprised big-band music, rock bands, religious songs, choral works, a dance performance and speeches by other DLM leaders. Media events included press conferences and an impromptu debate.

Millennium '73 received wide publicity. Rennie Davis, a prominent anti-war activist and member of the Chicago Seven, helped draw attention to the event as a spokesman for the DLM. A number of notable journalists attended, some of them acquaintances of Davis from the New Left. Later writers included it among the major events of 1973 and the 1970s. It was called the high point of Guru Maharaj Ji's popularity and the most important development in the American DLM's history.

Attendance was estimated at about 20,000, compared to the projected 100,000. Scholars and journalists generally depicted the event as a disappointment, and this, along with other factors, led to changes in the DLM's structure, management and message. A month after the festival, Maharaj Ji came of age and took administrative control of the US DLM.

Before the event

Background

Hans Ji Maharaj, who taught secret meditation techniques called "Knowledge" or kriyas,[6][7] founded the Divine Light Mission (DLM) in India in 1960. He died six years later, and his youngest son, then just eight years old, succeeded him as spiritual leader and Perfect Master. As he was a minor, his mother, Mata Ji, and the eldest son, Bal Bhagwan Ji, managed the DLM's affairs.[8][9] By 1971, when the 13-year-old Guru Maharaj Ji made his first tours of the UK and US, the Indian DLM claimed over five million members (known as premies). Within two years, the DLM had as many as 50,000 members in the US, thousands more in the UK and other countries, and as many as six million in India. Most of the western followers were young people from the counterculture.[10][11]

Hans Jayanti, a festival to commemorate Hans Ji Maharaj's birthday on November 9, which Guru Maharaj Ji claimed was "the most significant event in human history", was the largest of three annual festivals celebrated by the DLM.[12][13] At the Hans Jayanti of 1970, Guru Maharaj Ji delivered his "Peace Bomb" address to a gathering of 1 million people.[14][15] The 1972 Hans Jayanti was attended by over 500,000 followers, including thousands from the US and UK who had flown to India on chartered 747s.[14][3] Mata Ji and the 22-year-old Bal Bhagwan Ji decided that the 1973 Hans Jayanti would be the first to be held in the United States rather than India.[16] Organizers planned it as a media event and invited hundreds of reporters from all over the country, hoping that the media would come to see Maharaj Ji in a positive light.[17][18][19] Western media coverage of the DLM had been quite negative up to that point, and many people were antagonistic toward Maharaj Ji and his movement based on what they had read in newspapers.[20] Organizers first called the event "Soul Rush",[19] but it later became "Millennium '73".

The media suggested that the Astrodome may have been chosen as the venue after a dream supposedly had by Guru Maharaj Ji in which all of his followers were in a dome while the outside world was destroyed.[21][22][23] It may also have been chosen because it did not have a union contract, which allowed DLM members to work as volunteers.[21] Evangelist Billy Graham had set an attendance record of 66,000 a year earlier with his Jesus Exposition,[24] and DLM organizers hoped to gain similar media attention.[25]

The movement invested all of its resources in the event,[26] The sum of US$953,177 was budgeted,[27] including $75,000 to rent the Astrodome and $100,000 for the publicity.[28] The DLM also paid for many of the international charter flights that brought followers to Houston.[29] Members were under pressure to contribute money to support the event.[30][31]

Millennarian appeal

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, many people in the US, especially hippies, believed that the world was on the verge of a new era, the Age of Aquarius. This new age was expected to be characterised by peace and love, harmony and understanding.[32][33] By the late autumn of 1973 there was an "apocalyptic chill in the air",[2] as headlines dealt with the Vietnam war, the Watergate scandal, the Agnew resignation, a war in the Middle East, an energy crisis, mass murders in Houston and California, and UFO sightings across the South.

In a meeting with members, DLM President Bob Mishler denied that the event would start the millennium and said they called it "Millennium '73" because the word "millennium" evoked the "vision of one peaceful world based on spiritual values".[34]

Sociologist James V. Downton wrote that the millennarian appeal of the DLM prior to the festival sprang from a belief that Guru Maharaj Ji was the Lord, and that a new age of peace would begin under his leadership. These hopes appealed to the counterculture youth of the time, who were disillusioned with earlier attempts at political and cultural revolution and who were turning their aspirations in a spiritual direction. Downton describes these aspirations as encouraging millennial beliefs within the DLM, including the "psychological trappings of surrender and idealization." He states the guru's mother, whose satsang was "full of references to his divine nature", aided these beliefs, as did the guru himself, "for letting others cast him in the role of the Lord." Maharaj Ji's appeal to followers to give up beliefs and concepts did not prevent them "from adopting a fairly rigid set of ideas about his divinity and the coming of a new age."[35]

Promotion

Prominent anti-war activist and Chicago Seven defendant Rennie Davis, who first met Guru Maharaj Ji in February 1973,[36] quickly became the Mission's most visible member. He was appointed vice president of the organization a short time later and served as general coordinator for the Millennium festival.[37] His conversion, described as moving from chants to mantras, was the topic of numerous newspaper articles, as it reportedly shook the New Left from coast to coast.[38][39] An energetic promoter of his new guru and of Millennium '73, he traveled across the United States on a 21-city tour,[40] speaking to what he said were about a million people a day through radio and television interviews,[2] telling people that the "way out of the collision course civilization is on" was Guru Maharaj Ji.[2] He was not always well received, particularly by his former comrades in the peace movement (one Berkeley newspaper had the headline "Rennie Unites Left – Against Him"), and he was the target of heckling, tomatoes, and rotten eggs.[41][42][40] The Chicago Seven retrial was underway in the fall of 1973, and the judge gave Davis a dispensation to attend the festival.[2] Several associates of Davis from the left also attended, some as journalists.[43]

A two-week, eight-city, 500-person tour, called "Soul Rush", was organized to promote the festival.[44] At a stop in Washington D.C. premies gathered in front of the White House and invited President Richard Nixon to attend the festival and receive Knowledge.[2][45] One reporter who traveled in the tour wrote that they had little press coverage and poor attendance but showed obvious energy, and that the tour itself went remarkably smoothly with expressions of love among the members.[43] At each city, the touring group and local premies (DLM members) paraded in the morning, and a drama troupe performed in the afternoon.[46] The main event was the free evening performance by "Blue Aquarius", a 50- to 60-piece band led by Bhole Ji, Maharaj Ji's 20-year-old brother, referred to as the "Lord of Music" by Davis and others.[47][48] The band, composed of professional and amateur musicians who donated their efforts, also anchored the Houston festival. The leading member was drummer Geoff Bridgeford, formerly of the BeeGees.[2][49] One spectator, impressed by the good spirits of the marchers, donated money and said, "If this is what I see on these kids' faces, I want it."[50]

Press releases and a festival poster announced that the event would mark the beginning of "a thousand years of peace for people who want peace,"[2][3] the idea being that peace could come to the world as individuals experienced inner peace.[51] A flyer said, "Now the turning point in human civilization is here. ... The Dawn of the New Age."[52] The "Call to Millennium" said that "Guru Maharaj Ji has proved to us that an age of peace is possible, now, ... Peace is needed. And peace shall be obtained. ... [Guru Maharaj Ji] will present to the world a plan for putting peace into effect."[5]

Expectations and rumors

Official DLM literature predicted the dawn of a new age of peace, the Age of Aquarius, and some followers expected dramatic change or even the Second Coming.[53][54] In a letter to premies inviting them attend the festival, Guru Maharaj Ji said, "This is a festival not for you or me. It is for the whole world and maybe the whole universe". He urged them to support the festival, saying, "Isn't it about time you all get together and help me bring peace to this Earth?"[55] Rennie Davis promised that a practical plan for world peace would be revealed.[56]

A scholar noted that some premies made "many rather bizarre, 'cultic' predictions" which reflected their excitement about the event as well as authenticated its significance.[57] A member remarked that even normally realistic followers were swayed by the collective fantasies.[58] According to Sophia Collier, a minority of members, mostly limited to Houston, became Victims of Millennium Fever and Bal Bhagwan Ji was the fever's carrier.[59] The majority of the premies repeated Bal Bhagwan Ji's ideas out of astonishment, but some actually believed him.[60] Journalists noted that some followers perceived the predicted appearance of Comet Kohoutek as an omen, as a spaceship on its way to Houston, or as the return of the Star of Bethlehem.[2][21][61]

A frequently repeated prediction, attributed to Maharaj Ji, was that the Astrodome would levitate.[2][62][63] There were "wild rumors spread half in jest" by Davis and others, that extraterrestrials would attend.[53][61][64] When a reporter at the festival asked Bal Bhagwan Ji about the predicted aliens, he replied, "If you see any, just give them some of our literature."[21] He was also said to have predicted that earthquakes in New York and Denver, along with a dive in the stock markets, would precede the festival.[65][2]

Public predictions of attendance grew larger: from 100,000 to 144,000 (the number foretold in the Book of Revelation for the Second Coming),[61] to 200,000 and even 400,000.[66] (The capacity of the Astrodome was 66,000.)[67][51] Davis told one audience that millions would attend.[68] Downton said that there were runaway expectations about attendance.[69]

Bob Mishler later said he had tried to "put the brakes on" growing expectations. Mishler said he toured the country explaining to members that the festival would be significant because of what happened there, not because of the number of attendees. He said he only expected 20,000–25,000, but "it was like calming a team of wild horses to stop the predictions of hundreds of thousands and the Astrodome taking off into outer space ... The aim of life is not to fly off to another planet. It is to establish peace right here in our own life, right down here."[70]

Millennium '73

Rainbow Brigade

During the summer prior to the festival, 380 followers worked full-time in Houston preparing for the event.[71] Known as the "Rainbow Brigade," their motto was "Work Is Worship".[2] The total staff for the festival eventually numbered 4,000.[43] Fifteen hundred festival volunteers stayed at a former Coca Cola plant, renamed the "Peace Plant" for the occasion, where they slept on folded blankets over the concrete floor.[72][2] Another thousand stayed at the Rainbow Inn.[43] Reporters wrote that the amateur volunteers maintained a tight and professional operation,[52] and showed the egalitarian obedience of the Israeli Army or "a wall-less, coeducational monastery".[21] One reporter noted that the workers seemed to be "model human beings, perhaps even on their way to becoming the 'new evolutionary species' that they claim will establish heaven on earth."[2]

World Peace Corps

The World Peace Corps (WPC), headed by Maharaj Ji's 19-year-old youngest brother, Raja Ji, was the DLM's security force at the event. He said its job was "to make sure that whatever is happening, happens correctly."[5] The WPC members at the festival were reported to be mostly English followers.[17] One of the WPC's main jobs was keeping followers away from their guru.[2][73]

The World Peace Corps' name was called doublespeak and compared to the Big Lie.[74][17] They were seen by one reporter as "threatening, cajoling and generally pushing everyone around",[61] by another as "a Guru goon squad of tough-looking teddy boy types from Britain",[52] and by a member as a "corps of sweet-looking ushers and more brawny strongarms."[75] Described as dour and brutal,[39][76] they were seen by one reporter as exemplifying "the inevitable violence of any millennial sect hell-bent on abstract purity and infinite happiness."[39] One observer was quoted as saying, "These people were mad with a sense of divinity-authorized power. It was like descending into the ninth ring of hell."[77]

And It Is Divine special issue

The DLM's glossy magazine, And It Is Divine, published a special edition for the event. The 78-page magazine, with Maharaj Ji listed as the Editor-in-Chief, included an invitation to the event, the festival program, and a history of the festival. One article profiled the Holy Family (Guru Maharaj Ji, his mother, and three older brothers), illustrated with individual portraits and a group photograph. The festival invitation said that, "Three years ago, at the 1970 Hans Jayanti, the present Guru Maharaj Ji proclaimed he would establish world peace. This year at Millennium '73 he will set in motion his plan to bring peace on earth ... for a thousand years." An article compared the nations of the world to the Roadrunner who, blinded by the prize he is chasing, runs of the end of the cliff and falls.[5]

An unsigned article, titled "Prophets of the Millennium", referred to prophecies from the Book of Isaiah, Hindu scripture, American Indians, Edgar Cayce, Jeanne Dixon, and others. The article noted that "prophecies have a way of coming true", that "predictions the Lord will return as a child appear in almost every part of the World", and that "many prophecies say the Savior will come from the East." It asked, "Is Guru Maharaj Ji the great Savior that all people of the world are expecting?" and answered by saying that "everyone must decide for himself."[5]

Hobby Airport arrival

The first big event of the festival was the arrival of Guru Maharaj Ji and the Holy Family on Wednesday, November 7, 1973.[39] The crowd of 3,000 followers, "uniformly young, bright-eyed and clean-cut", waited for two or three hours at Hobby Airport.[2][28][43] While they waited, premies covered Maharaj Ji's emerald-green Rolls Royce with flowers. One said "What do you expect him to do, travel from LA. to Houston on a donkey? Christ came on humble; well Guru Maharaj ji comes on like a king, we want him to have the best."[21] After his late arrival, Maharaji Ji spoke for a few minutes, saying, "It's really fantastic and really beautiful to see you here, the Millennium program will start tomorrow and it'll really be fantastic, it'll be incredible ... and soon people will get together and finally understand God. ... There's so much trouble in the world, Watergate is not only in America, it exists everywhere."[61][39] He also said, "And I think it's about time people found out who God is by now at least."[79][17] A journalist described the scene as reminiscent of the Great Awakenings, and the revivalism which has been part of American history, and observed the peculiar encounter between two absolute opposite ends of the religious spectrum: India's unstructured spirituality and the despiritualized and pragmatic American religionism.[39]

The Holy Family stayed in the Astrodome's six-bedroom, $2,500 Celestial Suite.[80] Rennie Davis commented on the cosmic appropriateness of the names of the suite and of the master bedroom, and of the faucets shaped like swans (the guru's symbol).[81] He said that the Astrodome was built for the festival,[74] a sentiment which an Astrodome manager said was shared by every religious group that held an event there.[82][43]

Stage, signs, and effects

Award-winning architect and follower Larry Bernstein said he designed the stage, not for the audience in the Astrodome, but for the TV cameras.[52] The Template:Ft to m multilevel set fit easily at one end of the field under the dome's Template:Ft to m roof. The set, made of glowing white Plexiglas, was described as striking in appearance.[61] Objectively large, it was reportedly dwarfed by the vast size of the Astrodome.[21][52][83] At the highest level was the guru's throne. Lower levels held the Holy Family, the Mahatmas (sometimes described as the priests or apostles of the DLM),[84] and the Blue Aquarius band led by Bhole Ji Rawat, who wore a silver-sequined suit while conducting.[51] Red carpeting covered the Astroturf.

Projected on huge white screens above the set were rainbows and images of the turmoil of the 1960s.[28][2] The Astrolite, Astrodome's huge electronic signboard, flashed animated fireworks (the same that were shown during ballgames),[52][27] representations of Maharaj Ji,[39] and a variety of slogans, scriptural citations,[2] and announcements:

- Sugar is Sweet/So are You/Guru Maharaj Ji [52]

- The Holy Breath will fill this place/And you will be baptized in Holy Breath [52][43]

- All premies interested in doing/Propagation in Morocco please contact/Millennium Information at the Royal Coach Inn [52]

- Happiness is not in the material world. It is the property of God [49]

- Attention, Attention/Please do not run and dance/Thank you, Guru Maharaj Ji [74]

- Realize heaven on earth [2]

- You will sit in your assigned places, please [85]

Program

According to reports before the festival, the three themes of the festival were to be, "Who is Guru Maharaj Ji", "Guru Maharaj Ji is Here", and "The Messiah Has Come".[19][86] Each day's program opened and closed with the singing of Aarti, called an "ancient devotional song of praise to the Perfect Master".[5] Maharaj Ji was reported to have watched the proceedings on closed-circuit television in his suite,[30] and to have sent his bodyguard down with a can of pink foam confetti to spray the crowd on his behalf, reportedly an example of lila.[2] In addition to the main program, mahatmas were conducting initiations into Knowledge at local ashrams, and the guru and his family were offering darshan, or holy presence, to initiates.[87]

Day 1: "What is a Perfect Master?"

The first day of the festival was Thursday, November 8, 1973. The program listed the topic of the day as "What is a Perfect Master?"[5] The program started at noon with an oratorio composed for the occasion by Erika Anderson.[5] The masters of ceremony were Joan Apter, an early US convert and one of Maharaj Ji's secretaries, and Charles Cameron, one of the guru's earliest converts in the UK and editor of Who Is Guru Maharaj Ji?[39] Cameron told stories of previous Perfect Masters. After that came a pageant reenacting scenes from the life of Jesus Christ.[39][5] In the afternoon, Bal Bhagwan Ji delivered a spiritual discourse, or satsang.

Rhythm and Blues musician Eric Mercury performed during the dinner interval. Stax Records had negotiated an agreement with the DLM to make a recording of the event in exchange for showcasing Mercury, one of their new acts. They had already released an album titled "Blue Aquarius" in 1973 that was on sale at the event. Mercury, a Canadian of African ancestry and the only non-member who performed, ended up playing to an audience of 5,000 or fewer.[85] Stax recorded the performance and Mercury said at a press conference that he would give 50 percent of his royalties from the album to the DLM.[88] He later told a reporter that while he was interested in the message initially he was put off by the pressure to join for what he perceived as an effort to gain ethnic diversity.[89]

Following Mercury was a speech by Bob Mishler, the founding president of the DLM in the United States, and then an hour-long set by the Blue Aquarius orchestra.[5] The highlight of the evening was a satsang by Maharaj Ji:[90]

You want to be the richest man in the world? I can make you rich. I have the only currency that doesn't go down ... People think I'm a smuggler. You betcha I am. I smuggle peace and truth from one country to another. This currency is really rich. But if you think I'm a smuggler then Jesus Christ was a smuggler and so was Lord Krishna and Mohammed.[43][51]

Maharaj Ji said to the crowd, "Try it, you'll like it."[85][3][51] (This was the catchphrase from a popular 1971 ad campaign for Alka Seltzer.)

Day 2: "The Perfect Master is Here"

The second day of the festival, Friday, November 9, had the theme of "The Perfect Master is Here". It featured speeches by mahatmas and by Maharaj Ji's mother, Mata Ji. The Divine Light Dance Ensemble performed a dance piece, Krishna Lila, that one reporter called "beautifully choreographed and executed".[52] Music included another choral composition by Erika Anderson, another long set by Blue Aquarius, and a performance by the Apostles, a devotional rock band. Maharaj Ji wore a red Krishna robe and later put on a jeweled crown of Krishna,[43][2] the "Crown of Crowns for the King of Kings".[61][28] His satsang that night included this story:[52][27][91]

Imagine if you wanted a Superman comic real bad. And you go all over asking people if they've got one. You go to all the bookstores and to all the kids in the colleges, and all the people on the streets and no one has one anywhere. And you're real depressed and you're sitting there in the park and this little kid comes up and says "Hey man, how'd you like a Superman comic." And you say, "G'wan. You don't have one." And this kid pulls it from out of his shirt and it is a genuine; a gen-u-ine Superman comic: and you look at it and say, "Hey man; this must be very expensive," and he says, "No, take it, it's yours. It's free." And you don't believe him but then you take it. He just gives it to you. Well if you can imagine that, you can imagine what Knowledge would mean to you.[43]

Day 3: "World Assemblage to Save Humanity"

The third and last day of the festival, Saturday, November 10, was called a "World Assemblage to Save Humanity". A talk by another brother, Raja Ji, and more performances by Blue Aquarius and the Apostles filled the schedule. Plans for the Divine United Organization and the Divine City were announced. Rennie Davis gave a speech that one reporter called the oratorical high point of the festival. He said to the gathering, "All I can say is, honestly, very soon now, every single human being will know the one who was waited for by every religion of all times has actually come"[51] and "I tell you now that it is springtime on this earth!"[27] Jerry Rubin, a co-defendant in the Chicago Seven trial, said he had never heard Davis sound more dangerous.[43]

The climax of the event was the final satsang by Maharaj Ji, in which he laid out his plan for peace. According to one reporter his basic message was, "You want peace? Give me a try. Let me have a try. I'll establish peace. It's a simple deal."[27] One analogy by Maharaj Ji that several reporters noted compared the techniques of Knowledge to a fuel filter:[39][92]

The thing is that this life is a big car, and inside the car there is a big engine. And in the engine there is a carburetor, which is hooked up to a fuel line. In some cars, before the fuel line hits the carburetor, there is a thing called a filter that makes sure the fuel going into the carburetor is pure. So in this life, the filter for our minds is the Knowledge, and if we are not being filtered properly, many dirty particles enter our minds and eventually the whole engine is destroyed.[2]

Following his talk he was presented by grateful premies with a golden sculpture of a swan and a marble plaque depicting a lion and a lamb lying down together.[51] The event concluded after a short performance by the Blue Aquarius orchestra. After the program, volunteers hurried to clear the field of the stage and carpeting in time for a football game the next afternoon.[39]

Attendance

Notable members attending the event Sophia Collier, Rennie Davis, Timothy Gallwey. Journalists, writers, observers, and guests included James Downton, Marjoe Gortner, Wavy Gravy, Robert Greenfield, Paul Krassner, Bob Larson, Annie Leibowitz, Jerry Rubin, Robert Scheer, Michael Shamberg, John Sinclair, and Loudon Wainwright III.[93][94][21]

Overall attendance was most commonly estimated at 20,000, with other estimates ranging from 10,000 to 35,000.[95] Chartered planes brought followers from several dozen countries.[96][3] Seating sections were designated for attendees from France, Sweden, India, Spain, and even, as a joke, Mars.[97] In addition to the seats reserved for the ETs within the stadium, a corner of the parking lot was set aside for their ship.[74][21][98] Bal Bhagwan Ji reportedly told a follower who asked about the low attendance that there were actually 150,000 beings there.[43]

The premies were reported to be "cheerful, friendly and unruffled, and seemed nourished by their faith".[21] Unlike most youth gatherings of the era, there was no scent of marijuana or tobacco, only incense.[27][52] Though the movement's membership included former "political radicals, communards, street people, rock musicians, acid-head 'freaks,' cultural radicals, [and] drop-outs",[99] they now appeared clean-cut and neatly dressed.[2] The men wore suits and ties, and the women wore long dresses.[49][19]

When Maharaj Ji was present, his followers raised their arms towards him.[100] They chanted "Bolie Shri Satgurudev Maharaj ki jai!" ("All praise to the Perfect Master, giver of life").[100] One reporter called them "cheerleaders".[21] Four journalists compared it to scenes at the Nuremberg stadium.[61][101][102][103]

Four hundred parents of DLM members sat in a special section high above the floor of the dome. To many parents, Maharaj Ji was "a rehabilitator of prodigal sons and daughters".[21] One mother explained how her son had stopped using drugs and was happier after receiving Knowledge, and that she had been initiated, too.[100] One follower said some of the parents looked a little embarrassed.[39]

Opposition groups

Local Baptist churches took out a full-page newspaper advertisement warning of false prophets.[2] Hare Krishna, Jesus Freaks, Children of God and the Jews for Jesus protested loudly and sought converts.[85][52] Members of the Christian Information Committee drove from Berkeley, California.[27] One Christian evangelical anti-cult group,[104] Spiritual Counterfeits Project, had its origin in the event.[105]

The picketing groups fought with each other, harassed attendees, and reportedly vandalized cars owned by DLM members.[39] Organizers called the police to clear Hare Krishna protesters who were blocking the arena entrances and as many as thirty-one of them were arrested for disorderly conduct.[52][2][38] The Hare Krishnas protested that Maharaj Ji was being called an incarnation of Krishna, while the Jesus Freaks protested that Maharaj Ji was a false messiah and the antichrist.[57] In response, Maharaj Ji said at one of his satsangs, "They must be drunk. When the real antichrist comes they won't even recognize him. He'll be too professional."[2][51]

Media coverage

Between fifty and three hundred reporters covered the event.[61][106] It received extensive coverage from the print media though not from the national television news coverage that organizers expected (there had been predictions that Walter Cronkite would cover the event live).[19][39][61] The New York Times and Rolling Stone both sent two reporters each, and it was also covered by the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, the Los Angeles Free Press, the Detroit Free Press,[39] the Village Voice, The Rag of Houston, and the Houston Chronicle. Magazines covering the festival included Time, Newsweek, the New York Review of Books, Ramparts Magazine, Creem, Texas Monthly, The Realist, Crawdaddy, Playboy, Penthouse, and Oui. Four journalists, Marilyn Webb, Robert Scheer, Robert Greenfield, and Ken Kelley, had been following or even living with the DLM for weeks or months prior to the festival.

KPFT-FM, a local progressive radio station covered the event:[107] Paul Krassner, John Sinclair, Jeff Nightbyrd, and Jerry Rubin were co-anchors, and Wavy Gravy and Loudon Wainwright III made guest appearances.[52][107] The anchors reportedly mocked the festival and its attendees.[107] Not realizing this, the festival organizers piped the signal throughout the Astrodome until the nature of the coverage became apparent.[107] Wainwright said that Maharaj Ji partly inspired the song "I am the Way".[108]

Top Value Television (TVTV) chose the Millennium '73 festival as a topic for a documentary, titled "Lord of the Universe". TVTV was a documentary production company that had just received acclaim for its groundbreaking piece on the 1972 Republican National Convention. They used Portapak cameras and newly developed recording technology that allowed them to shoot handheld video of broadcast quality. Two teams followed a member and the Soul Rush tour prior to the event. Led by producer Michael Shamberg, five camera teams recorded 80 hours of video at the festival itself. Chicago Seven codefendant Abbie Hoffman, who did not attend, provided commentary. Collier noted that "it seemed that every time something weird would happen or some premie would make a dumb fanatical or ill-conceived remark–flash–on would go the TV lights and the TVTV crew would start filming."[109] PBS television stations across the US broadcast the documentary in the spring of 1974 and again in the summer. It went on to win a DuPont-Columbia Award for excellence in broadcast journalism.[110][111][112]

Reporters wrote of being kept waiting for hours on the airport tarmac in the heat and humidity in order to cover an appearance that lasted only a few minutes. Rules and passes for media access were changed daily with no apparent logic.[17] A female reporter wrote of being shoved a few times by WPC members.[39] The New York Times reporter wrote "I never saw a premie lose his temper or say an unkind word".[21] Another reporter said the DLM assigned him a "premie guide" to accompany him at all times to answer questions.[2] Robert Scheer later wrote of being told by a press agent that the Venutians were landing and he could be the first to cover them if he hurried out to the parking lot.[113] Scholars say that the reporters were angered and alienated.[114] Collier complained about the coverage in general and especially about an article by the Village Voice's Marilyn Webb that featured her: "The article went on and on as if she were being paid by the word, no matter how trivial or inaccurate, obscuring and misrepresenting my actions and beliefs. ... This was only one of many hundreds of such articles about the festival."[115] By one account, the national press "bristled with questions, concerned only with costs and the chain of organization, refusing to feel the Knowledge."[28]

According to Collier, journalists found the event a "confused jumble of inarticulately expressed ideas."[116] One reporter complained of the lack of content, saying, "They didn't have much to say, and they said it over and over again."[52] Davis told reporters that he was aware of the perceptions of the event by outsiders, and admitted that the huge stage, flashing lights, and a kid giving parables about cars did not make for a good show.[51]

The DLM's Divine Times newspaper printed an analysis of the press coverage the following June. It criticized the many articles written about the festival, saying they portrayed Maharaj Ji as "materialistic and his followers as misguided and misled". The only article it approved of was in a children's magazine. The review also admitted that the DLM had made a number of mistakes and that the press relations were improper and inept. Carole Greenberg, head of DLM Information Services, said, "We took something subtle and sacred and tried to market it to the public." She said the press had done the movement a favor by holding up a mirror that showed "the garbage we gave them." The article went on to say that the greatest botch was Guru Maharaj Ji's press conference.[106]

Maharaj Ji's press conference

Maharaj Ji's press conference, hastily arranged for the morning of Friday, November 9,[61] was noted for leaving the reporters frustrated and hostile because of what they described as flippant, manipulative, and arrogant answers, and because of an effort to pack the room with supporters.[114][106][17] According to the Divine Times some of the reporters acted like "district attorneys interrogating a hostile witness".[106] Several dozen followers, mostly foreign, jostled reporters, asked long and complimentary questions, and shouted "Boli Shri" or "Jai Satschadan" following the answers.[106][61][17]

- Question: Are you the messiah?

- Answer: Please do not presume that. I am a humble servant of God, trying to establish peace in the world.[51][2][117]

- Q: Why is there such a great contradiction between what you say about yourself and what your followers say about you?

- A: Well, why don't you do me a favor ... why don't you go to the devotees and ask their explanation about it?[2][3][39]

- Q: It's hard for some people to understand how you personally can live so luxuriously in your several homes and your Rolls-Royces

- A: That life that you call luxurious ain't luxurious at all, because if any other person gets the same life I get, he's gonna blow apart in a million pieces in a split of a second. ... People have made Rolls-Royce a heck of a car, only it's a piece of tin with a V8 engine which probably a Chevelle Concourse has.[2][3][39][118]

- Q: Why don't you sell it and give food to people?

- A: What good would it do. All that's gonna happen is they will need more and I don't have other Rolls-Royces. I will sell everything and I'll walk and still they will be hungry.[2][3][21][61][117]

- Q: Guru, what happened to the reporter in Detroit who was badly beaten by your followers? [Following the question, Maharaj Ji's press aide tried to change the subject, accusing the questioner of hogging the floor.][2][39][119]

- A: I think you ought to find out what happened to everything.[2][39][28]

A reporter from Newsweek complained that the evasive responses reminded him of a recent Watergate press conference with White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler, "I expect you to announce three weeks from now that all these statements are 'inoperative'."[61] The conference, which lasted nearly an hour,[120] ended shortly after reporters pressed for information about the Detroit incident, in which a person who had thrown a pie at Maharaj Ji a few months prior was subsequently beaten by two DLM members.[39] One observer said the conference "took on a bizarre Nixonian character" before descending into shambles.[17] As of 1976, it was Maharaj Ji's last press conference.[121]

Krassner–Davis debate

Paul Krassner repeatedly challenged Rennie Davis to a debate and Davis finally agreed. It was held in the adjoining Astrohall convention center on the third day, Saturday, November 10, and attended by 30 reporters.[122] The question was, "Resolved: That Davis has copped out to turn kids away from social responsibility to personal escape". Ken Kelley was the moderator and KPFT-FM broadcast it live.[123][52] Repeating accusations he had been making through the summer, Krassner said that the movement was part of a CIA-directed conspiracy.[21][124][2][125] He called it a neo-Fascist discipline and said Maharaj Ji was a mystic hired to seduce the youth movement into oblivion.[126] Krassner said Guru Maharaj Ji was the spiritual equivalent of Mark Spitz.[127] He asked, "Did the Maharaj Ji give Richard Nixon a secret contribution?", to which Davis replied, "Yes–he gave Richard Nixon his life."[39]

Davis said the most important point was that "the Lord is on the planet and he has the secret of life", and that Maharaj Ji would lead "the most serious revolution ever to take place in the history of the world". He said the main battleground now is "the struggle between the mind and the soul" in each person.[2] Reporters said that Davis stayed poised while Krassner heckled.[74][126][52]

Afterwards

Millennium '73 was called the youth culture event of the year by two sociologists.[128] Journalists listed it among the notable events of the 1970s.[129][130] Vishal Mangalwadi called the festival the zenith of Maharaj Ji's popularity.[131]

According to journalists and others, the festival did not live up to expectations of establishing peace or world transformation, there were no ETs, and the Astrodome did not levitate.[2][52][27][132] Journalists and scholars called the festival a dismal failure,[133] a fiasco,[134] a major setback,[13] a disastrous rally,[135] a great disappointment,[136] and a "depressing show unnoticed by most".[74] According to one scholar, James T. Richardson, the event left the movement "in dire financial straits and bereft of credibility".[137] Religious scholar Robert S. Ellwood wrote that Maharaj Ji's "meteoric career collapsed into scandal and debt" after the event.[138]

Maharaj Ji gave no public indication that he was disappointed,[3] although one reporter said he appeared to be nonplussed by the turnout.[39] He remarked privately on how perfect it was and called the event fantastic.[139] Three months after the event Davis said, "I don't feel as I suppose people think I should, which is, 'Oh boy, did I blow it!' ... Generally I said the event was significant not because of numbers but because we saw it as the changing of an age. Twelve people came to the Last Supper. How many came to the Sermon on the Mount?"[140] In an interview the following June, Mishler said that, "The positive vibration of love that engrossed all those people in the Astrodome marks the beginning of the human race. [...] People who came with expectations went away disappointed, but those who perceived ahead of time what would happen dealt with the situation that remained. Those who expected nothing in particular just went on with life and were happy to have attended."[139]

Some members expected world transformation and there were many reports of members being disappointed.[141][142][143][144][145] According to sociologists Foss and Larkin, some members saw the failure to meet expectations as another example of lila.[146] Downton, who attended the festival, said the followers tried to find nice things to say about the event but that it appeared to him they were trying to hide "ruined dreams".[147] One member said that followers could not believe they "would have to go on living in the same old world ... The excitement was over."[148] Another member, from an Orthodox Jewish background, was disenchanted and began to doubt that Maharaj Ji held all the answers.[149] Janet McDonald, an African American woman attending Vassar College, said that her "faith was brutally dashed to bits" at the festival due to its failure to meet her expectations of miracles and by her embarrassment at lining up for hours to kiss the white-socked foot of Mata Ji. She left the movement soon after.[150] Sophia Collier said that she woke up on the bottling plant floor the next morning wondering "What the hell am I doing here?", though she stayed to try to fix the movement's public image.[115]

Debt

Admission to Millennium '73 was free,[21] unlike other DLM festivals that charged sizable fees.[151] The DLM leadership had expected that a huge attendance would be followed by generous donations.[53] Despite fundraising beforehand, lower than expected attendance and mismanagement left the DLM in serious debt.[57] The organization's debt was estimated at $682,000,[152] and individual members also carried debts incurred for traveling expenses.[153]

The festival was financed with short-term credit that began coming due right after the event.[154][139] Creditors, including the Astrodome management, pursued the DLM seeking payment. Equipment and property belonging to the mission were repossessed.[155] By mid-1974, NBC reported that about $150,000 was still owed and that 25 vendors had received no payments at all.[156] Members of the DLM took on extra work in order to raise money, at Maharaj Ji's suggestion.[2][157][158] The debt forced the sale or closure of the DLM's printing and other businesses, the temporary shutdown of their newspaper and magazine,[75][159][160] the cancellation of the IBM computer lease and all but one WATS line,[161][162] the disbanding of Blue Aquarius,[106] and the shelving of new initiatives.[148] In 1976, a DLM spokesman said that the debt had been reduced to $80,000 and that the mission was on a sound financial footing.[163]

Impact

The event had a major impact on the movement. One sociologist wrote that it was the most important development in the American movement's history.[57] The movement had lost its millennial dream of world peace, according to Downton.[164] The failure to meet expectations, along with the debt and bad press, led to significant changes in the movement.[165]

Scholars describe 1973 as the peak year of the movement,[166][167] or mention a significant drop in new followers.[168] The financial crisis required retrenchment and reorganization.[57][148][169] Meanwhile, Maharaj Ji was coming of age and taking greater responsibility. A month after the festival he turned 16 and took administrative control of the DLM's US branch.[13] He received court permission to marry the following May, making him an emancipated minor. His move to take control of the US DLM and his marriage to a Westerner caused a rift within the family that resulted in the movement being split between a Western branch, led by Maharaj Ji, and an Indian branch, run by his mother and Bal Bhagwan Ji.[170] Collier, writing after the fact, speculated that Maharaj Ji had acquiesced to the grandiose plans of his eldest brother and mother for Millennium '73 in an effort to keep the peace within the family, or at least delay a confrontation until he was an adult.[171]

The failure of Millennium '73 led the Western branch to shift away from Indian influences and trappings, according to some observers.[172][173][133][168] A Sikh scholar, Kirpal Singh Khalsa, wrote that the DLM "no longer projected itself as a movement that would include all of humanity in its membership."[168] The Western DLM moved away from its ascetic, "world-rejecting" origins and adopted a "world-affirming position".[133] Beginning in 1982, Guru Maharaj Ji changed the DLM into the more loosely organized Elan Vital. He became known as Maharaji or Prem Rawat and was presented as an inspirational speaker.[133] Bal Bhagwan Ji became known as Satpal Rawat, and his branch is now known as Manav Utthan Seva Samiti.[174] Both the Western and Indian branches have celebrated Hans Jayanti again since 1973.[175][176]

Notes

- ^ Larson 1982, p. 205

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Levine 1974

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Moritz 1974

- ^ Galanter, 1999 & p21

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j And It Is Divine 1973

- ^ Melton 1992, p. 143

- ^ Rawson 1973

- ^ Downton 1979, ch. 12

- ^ Geaves 2006

- ^ Downton 1979

- ^ Melton 1992, p. 217

- ^ Galanter, 1999 & p21

- ^ a b c Melton 1986

- ^ a b Jeremy 1974

- ^ Mangalwadi 1977, p. 219

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 191

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goldsmith 1974

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 5

- ^ a b c d e Winder & Horowitz 1973

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 5–7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Morgan 1973

- ^ Kelley 1974b

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 11

- ^ Rudin & Rudin 1980, p. 65

- ^ Ponte 1973

- ^ Lewis 1998, p. 84

- ^ a b c d e f g h Snell 1974

- ^ a b c d e f Kilday 1973b

- ^ Messer 1976, p. 67

- ^ a b MacKaye 1973

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 133

- ^ Tacey 2004, p. 256

- ^ Rado & Ragni 1967

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 152

- ^ Downton 1979, pp. 199–200

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 40

- ^ Rawson 1973

- ^ a b Kent 2001

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w du Plessix Gray 1973

- ^ a b Greenfield 1975, p. 41

- ^ Rose 1973

- ^ Strand 1973

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Webb 1973

- ^ Vidville Messenger staff 1973

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 171

- ^ Collier 1978, pp. 162, 170

- ^ Top Value Television 1974

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 69

- ^ a b c Elman 1974

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 174

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Blau 1973

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Dreyer 1974

- ^ a b c Downton 1979, p. 6

- ^ Bromley & Shupe 1981

- ^ Maharaj Ji 1973a

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 176

- ^ a b c d e Pilarzyk 1978

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 188

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 154

- ^ Miller 1995

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kelley 1974a

- ^ Boyle 1985, p. 230

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 11

- ^ McCarthy 1974

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 154,162

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 159

- ^ National Park Service 2008

- ^ Pope 1974, p. 6

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 5

- ^ Mishler & Donner 1974

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 14

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 63

- ^ Rudin & Rudin 1980, p. 67

- ^ a b c d e f Scheer 1974 Cite error: The named reference "Scheer 1974" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Collier 1978, p. 188

- ^ Kelley 1974b, p. 150

- ^ Kelley 1974b, p. 150

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 145

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 56

- ^ Baxter 1974

- ^ TVTV 1974.

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 156

- ^ Cartwright 1974

- ^ Mangalwadi 1977, p. 218

- ^ a b c d Gortner 1974

- ^ Wallace 1973

- ^ McDonald 1999, p. 86

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 70

- ^ Van Ness 1973b

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 79

- ^ Levy

- ^ Maharaj Ji 1973b

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 52

- ^ Collier 1978

- ^ Attendance was estimated at 20,000 by Moritz 1974, MacKaye 1973, Larson 1982, p. 206, Rudin & Rudin 1980, p. 65, Geaves 2006, Collier 1978, p. 174, Kilday 1973a, Gray 1973, and Kelley 1974a. It was estimated by Houston Police to be 10,000, according to Baxter 1974. Foss & Larkin 1978 estimated 35,000.

- ^ Newsweek 1973

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 175

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 156

- ^ Foss & Larkin, quoted in Geaves 2004

- ^ a b c Kilday 1973a

- ^ Van Ness 1973a

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 71

- ^ Steve Haines (1973), quoted in Kent 2001

- ^ Lewis 2005, p. 90

- ^ Chryssides 1999, p. 352

- ^ a b c d e f Bass 1974

- ^ a b c d Walker 2004, p. 116

- ^ Lichtenstein 1974

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 174

- ^ Boyle 1997, p. 72

- ^ Adler 1974

- ^ O'Connor 1974

- ^ Scheer 1997

- ^ a b Downton 1979, p. 189

- ^ a b Collier 1978, p. 178

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 176

- ^ a b Greenfield 1975, p. 76

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 76

- ^ Boyle 1997, p. 80

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 77

- ^ UPI 1976

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 86

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 87

- ^ Kent 2001

- ^ Rose 1973

- ^ a b Kilday 1973c

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 87

- ^ Foss & Larkin 1978

- ^ Allen 1979

- ^ Carroll 1990, p. 248

- ^ Mangalwadi 1977, p. 219

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 176

- ^ a b c d Aldridge 2007, pp. 58–59

- ^ Lewis 1998, p. 84

- ^ Pluralism Project 2008

- ^ Chryssides 2001, p. 211

- ^ James T. Richardson in Kivisto & Swatos 1998, p. 141

- ^ Elwood 1993, p. 236

- ^ a b c Mishler & Donner 1974

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 275

- ^ Miller 1995, p. 364

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 189

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 176

- ^ McDonald 1999, pp. 85–86

- ^ Lane 2004, p. 75

- ^ Foss & Larkin 1978, p. 163

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 189

- ^ a b c Downton 1979, p. 190

- ^ Lane 2004, p. 75

- ^ McDonald 1999, pp. 85–86

- ^ Richardson 1982

- ^ Frazier 1975

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 274

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 166

- ^ Los Angeles Times staff 1975

- ^ Sims 1974

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 181

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 275

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 189

- ^ Messer 1976, p. 64

- ^ Espo 1976

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 183

- ^ UPI 1976

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 188

- ^ Rudin & Rudin 1980, p. 65

- ^ Price 1979

- ^ Aagaard 1980

- ^ a b c Khalsa 1986, p. 235

- ^ Olson 2007, p. 343

- ^ Lewis 1998, p. 301

- ^ Collier 1978, p. 160

- ^ Hunt 2003, p. 116

- ^ Downton 1979, p. 191

- ^ McKean 1996, p. 54

- ^ Manavdharam 2007

- ^ DUO staff 2000

References

- Aagaard, Johannes (1980), "Who Is Who In Guruism?", Update: A Quarterly Journal on New Religious Movements, vol. IV, no. 3, Dialogcentret, retrieved 2008-07-07

- Adler, Dick (February 23, 1974), "Videotape Explorers on the Trail of a Guru", Los Angeles Times, p. B2

- Aldridge, Alan (2007), Religion in the Contemporary World, Cambridge, UK: Polity, ISBN 0-7456-3405-2

- Allen, Henry (December 6, 1979), "Roaring Toward Apocalypse In a Decade That Almost Wasn't", Washington Post, p. C1

- "Special Millennium Issue", And It Is Divine, Denver, Colorado, November 1973

{{citation}}: Text "publisher Shri Hans Productions" ignored (help) - Bass, Jim (June 1, 1974), "Millennium Scoops The Press", Divine Times

- Baxter, Ernie (August 1974), "The multi-million dollar religion ripoff", Argosy, pp. 72, 77–81, #380

- Blau, Eleanor (November 12, 1973), "Guru's Followers Cheer 'Millennium' in Festivities in Astrodome", New York Times

- Boyle, Deirdre (Fall 1985), "Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited"" (PDF), Art Journal, pp. 228–232

- Boyle, Deirdre (1997), Subject to change: guerrilla television revisited, Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-504334-0

- Bromley, David G.; Shupe, Anson D. (1981), Strange gods: the great American cult scare, Beacon Press, ISBN 0-8070-1109-6

- Carroll, Peter N. (1990), It seemed like nothing happened: America in the 1970s, New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-1538-6

- Cartwright, Gary (April 7, 1974), "There's More Texas Than Technology in the Houston Astrodome", New York Times

- Chryssides, George D. (2001), Historical dictionary of new religious movements, Metuchen, N.J: Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-4095-2

- Collier, Sophia (1978), Soul rush: the odyssey of a young woman of the '70s, New York: William Morrow and Company, ISBN 0-688-03276-1

- Downton, James V. (1979), Sacred journeys: the conversion of young Americans to Division Light Mission, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-04198-5

- DUO staff (2000), Hans Jayanti, New Delhi: Divine United Organization, pp. 24–37

- du Plessix Gray, Francine (December 13, 1973), "Blissing out in Houston", The New York Review of Books, no. Volume 20, number 20, p. 36–43

{{citation}}:|issue=has extra text (help); External link in|title= - Eck, Diana L. (ed.), The Rush of Gurus, Columbia University Press

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|publication=ignored (help) reprinted on Pluralism Project (2008), http://www.pluralism.org/ocg/CDROM_files/hinduism/rush_of_gurus.php, retrieved 2008-08-22{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Elman, Richard (March 1974), "Godhead Hi-Jinx", Creem

- Ellwood, Robert S. (1993), Islands of the dawn: the story of alternative spirituality in New Zealand, [Honolulu]: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1487-8

- Espo, David (November 26,1976), "Followers Fewer, Church Retrenching for Maharaj Ji", The Charleston Gazette, p. 8C

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|service=ignored (|agency=suggested) (help) - Foss, Daniel A.; Larkin, Ralph W. (Summer, 1978), "Worshiping the Absurd: The Negation of Social Causality among the Followers of Guru Maharaj Ji", Sociological Analysis, 39 (2): 157–164, doi:10.2307/3710215

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Frazier, Deborah (March 1974), "Seventeen-year-old guru likes pizza and sports cars", UPI, The New Mexican

- Galanter, Marc (1999), Cults: Faith, Healing, and Coercion, Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-512369-7

- Geaves, Ron (2004), "From Divine Light Mission to Elan Vital and Beyond: an Exploration of Change and Adaptation", Nova Religio, 7: 45, doi:10.1525/nr.2004.7.3.45

- Geaves, Ron (2006), "Globalization, charisma, innovation, and tradition: An exploration of the transformations in the organisational vehicles for the transmission of the teachings of Prem Rawat (Maharaji)", Journal of Alternative Spiritualities and New Age Studies (2): 44–62

- Goldsmith, Paul (Summer 1974), "Lord of the Universe: An Eclairman In Videoland", Filmmakers Newsletter, pp. 25–27

- Gortner, Marjoe (May 1974), "Who Was Maharaj Ji? The world's most overweight midget. Forget him.", Oui

- Greenfield, Robert (1975), The Spiritual Supermarket, New York: Saturday Review Press/E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc., ISBN 978-1582340340

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Hunt, Stephen J. (2003), Alternative religions: a sociological introduction, Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-3410-8

- Jeremy, Kathleen (February, 1974), "Jet Set God", Pageant, pp. 30–34, Volume 20, number 20

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Khalsa, Kirpal Singh (1986), "New Religious Movements Turn to Worldly Success", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 25 (2): 233–247, ISSN 0021-8294

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Kelley, Ken (February 1974), "Over the hill at 16", Ramparts Magazine, pp. 40–44, #12

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kelley, Ken (July 1974), "I See The Light: In which a young journalist pushes a cream pie into the face of His Divine Fatness and gets his skull cracked open by two disciples", Penthouse, pp. 98–100, 137–138, 146, 148, 150–151

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kent, Stephen A. (2001), From slogans to mantras: social protest and religious conversion in the late Vietnam War era, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, ISBN 0-8156-2948-6

- Kilday, Gregg (November 9, 1973), "Astrodome Loses Beer Odor to Mystic Incense: 20,000 Devotees of 15-Year-Old Guru Assemble in Houston for 3-Day Festival", Los Angeles Times, p. A4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kilday, Gregg (November 13, 1973), "Under the Astrodome - Maharaj Ji: The Selling of a Guru, 1973", Los Angeles Times, p. D1

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kilday, Gregg (November 25, 1973), "Houston's Version of Peace in Our Time", Los Angeles Times, p. S18

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kivisto, Peter; Swatos, William H. (1998), Encyclopedia of religion and society, Walnut Creek, Calif: AltaMira Press, ISBN 0-7619-8956-0

- Lane, Lonnie (2004), Because They Never Asked, Xulon Press, ISBN 1-59467-466-3

- Larson, Bob (1982), Larson's book of cults, Wheaton, Ill: Tyndale House Publishers, ISBN 0-8423-2104-7

- Levine, Richard (March 14, 1974), "Rock me Maharaji - The Little Guru Without A Prayer", Rolling Stone Magazine, pp. 36–50 Also in Dahl, Shawn; Kahn, Ashley; George-Warren, Holly (1998), Rolling stone: the seventies, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 102–105, ISBN 0-316-75914-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Levy, Phil, "An Expressway over Bliss Mountain", East West Journal, p. 29

- Lewis, James P. (1998), Cults in America: a reference handbook, Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-57607-031-X

- Lewis, James P. (2005), Cults: A Reference Handbook, Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1851096183

- Lichtenstein, Grace (February 3, 1974), "They Won't Boo Loudon Any Longer", New York Times

- Los Angeles Times staff (March 23, 1975), "Newsmakers", Los Angeles Times, p. 2

- MacKaye, William R. (November 9, 1973), "Following the Guru To the Astrodome", Washington Post, p. 1

- McDonald, Janet (1999), Project girl, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-23757-3

- Maharaj Ji (November 1973), "A Letter From Guru Maharaj Ji, Bonn, Germany September 31, 1973", And It Is Divine, p. 2, Special Millennium '73 Edition

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Maharaj Ji (November 10, 1973), A Very Big Little Mystery, Houston, Texas

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Manavdharam (2007), Hans Jayanti, Ramlila Ground, New Delhi (16, 17 & 18 November 2007), Manav Utthan Sewa Samiti, retrieved 2008-08-15

- Mangalwadi, Vishal (1977), World of Gurus, Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd, India, ISBN 0-7069-0523-7

- Mangalwadi, Vishal; Hoeksema, Kurt (1992), The World of Gurus, Cornerstone Pr Chicago, ISBN 0-940895-03-X

- McCarthy, Colman (February 2, 1974), "Odd Couple In Religious Conversion", Winnipeg Free Press

- Melton, J. Gordon (1986), Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America, New York: Garland, ISBN 0-8240-9036-5

- Melton, J. Gordon (1992), Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America: Revised and Updated Edition, New York: Garland, ISBN 0-8153-1140-0

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|isbn2=ignored (help) - Melton, J. Gordon, Project Director; Lewis, James R., Senior Research Associate (1993), Religious Requirements and Practices of Certain Selected Groups: A Handbook for Chaplains by The Institute for the Study of American Religion, Institute for the Study of American Religion

{{citation}}:|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Messer, Jeanne. (1976) "Guru Maharaj Ji and the Divine Light Mission", in Bellah, Robert Neelly; Glock, Charles Y. (1976), The New Religious Consciousness, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-03472-4

- Miller, Timothy (1995), America's alternative religions, Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-2398-0

- Mishler, Bob; Donner, Michael, (June 1, 1974), "You Can't Imitate Devotion (interview)", Divine Times

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Morgan, Ted (December 9, 1973), "Oz in the Astrodome", New York Times

- Moritz, Charles (Editor) (1974), Current Biography Yearbook, New York: H. W. Wilson Company, ISBN 0824205510

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help) - National Park Service, Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record: Astrodome, retrieved 2008-08-22

- Newsweek staff (November 19, 1973), "'You're a Perfect Master'", Newsweek, pp. 157–158

- O'Connor, John J. (February 25, 1974), "TV: Meditating on Young Guru and His Followers", The New York Times, The New York Times Company

- Olson, Carl R. (2007), The Many Colors of Hinduism: A Thematic-Historical Introduction, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-4068-2

- Pilarzyk, Thomas (1978), "The Origin, Development, and Decline of a Youth Culture Religion: An Application of Sectarianization Theory", Review of Religious Research, 20 (1): 23–43

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ponte, Lowell (November 21,1973), "Turned On and Blissed Out: Setting of the Guru, 1973", Oakland Tribune

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Pope, Harrison (1974), The road East: America's new discovery of eastern wisdom, [Malaysia?]: Beacon Press, ISBN 0-8070-1126-6

- Price, Maeve (1979), "The Divine Light Mission as a social organization", The Sociological Review, 27: 279–296

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - Rado, James; Ragni, Gerome (1967), "Aquarius", Hair

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|Location=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Rawson, Jonathon (November 17, 1973), "God in Houston: The Cult of Guru Maharaji Ji", The New Republic, p. 17

- Richardson, James T. (1982), "The Divine Light Mission as a social organization", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 21 (3): 255–268

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - Rose, Frank (September–October 1973), "GURU", Fusion, #90

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Rudin, Marcia R.; Rudin, A. James (1980), Prison or paradise?: The new religious cults, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, ISBN 0-8006-0637-X

- Scheer, Robert (June 1974), "Death Of The Salesman", Playboy

- Scheer, Robert (April 1, 1997), "How I Was Stood Up by the Venusians: Even a brief encounter with a cult's absurdity reveals its power to attract", Los Angeles Times, p. 7

- Sims, Patsy (July 15, 1974), "Teen guru--God to some, a 'bunch of bunk' to others", Chicago Tribune, p. 1

- Snell, David (February 9, 1974), "Goom Rodgie's Razzle-Dazzle Soul Rush", Saturday Review World, pp. 18–21, 51

- Strand, Robert (November 4, 1973), "the Revival of Faith", UPI, Stars and Stripes, p. A4

- Syracuse Post-Standard staff (March 10, 1973), "15-Year-Old Guru Teaches 'Perfectness'", Syracuse Post-Standard, p. 3

- Tacey, David J. (2004), The Spirituality Revolution, Psychology Press, p. 16, ISBN 1583918744, 9781583918746

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Top Value Television (1974), "The Lord of the Universe", Electronic Arts Intermix, 1997-2007 Electronic Arts Intermix, retrieved 2008-04-04

- UPI (April 15, 1976), "Guru Maharaj Ji To Launch World Tour To Aid Mission", Playground Daily News, p. 3E

- UPI (November 25, 1978), ""Maharaj Ji has Jones-like traits"", Chronicle-Telegram, Elyria, p. A-3

- Van Ness, Chris (November 16, 1973), "Guru Maharaj Ji: Spiritual Fascism Part 1", Los Angeles Free Press

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Van Ness, Chris (November 23, 1973), "Guru Maharaj Ji: Spiritual Fascism Part 2", Los Angeles Free Press

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Vidville Messenger staff (October 25, 1973), "Round and About", The Vidville Messenger, Valparaiso, Indiana, pp. 1–5

- Walker, Jesse (2004), Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-9382-7

- Wallace, Andrew (August 3, 1973), "Thousands Bow At Guru Throne", Daily Mail

- Webb, Marilyn (November 22, 1973), "God's in his astrodome", Village Voice

- Winder, Gail; Horowitz, Carol (December 1973), "What's Behind the 15-Year-Old Guru Maharaj Ji?", The Realist, pp. 1–5, #97-C

External links

- Clayton, Lewis (October 29, 1973), "Singing Along With the Guru", The Harvard Crimson