Bonsai: Difference between revisions

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Notably, container-grown trees were popularized in Japan during China's [[Song Dynasty]], a period of cultural growth when the Japanese experienced and adopted their own versions of many mainland practices. At this time, the term for dwarf potted trees was {{nihongo|"the bowl's tree"|鉢の木|hachi-no-ki<ref>http://www.phoenixbonsai.com/Terms/Hachinoki.html</ref>}}, denoting the use of a deep pot. The c.1300 [[rhymed prose]] essay, ''Rhymeprose on a Miniature Landscape Garden'', by the Japanese Zen monk [[Kokan Shiren]], outlines aesthetic principles for bonsai, [[bonseki]] and garden architecture itself. At first, the Japanese used miniaturized trees grown in containers to decorate their homes and gardens.<ref>[http://www.arboretum.harvard.edu/plants/bonsai/intro.html "Early American Bonsai: The Larz Anderson Collection of the Arnold Arboretum" by Peter Del Tredici, published in ''Arnoldia'' (Summer 1989) by Harvard University]</ref> |

Notably, container-grown trees were popularized in Japan during China's [[Song Dynasty]], a period of cultural growth when the Japanese experienced and adopted their own versions of many mainland practices. At this time, the term for dwarf potted trees was {{nihongo|"the bowl's tree"|鉢の木|hachi-no-ki<ref>http://www.phoenixbonsai.com/Terms/Hachinoki.html</ref>}}, denoting the use of a deep pot. The c.1300 [[rhymed prose]] essay, ''Rhymeprose on a Miniature Landscape Garden'', by the Japanese Zen monk [[Kokan Shiren]], outlines aesthetic principles for bonsai, [[bonseki]] and garden architecture itself. At first, the Japanese used miniaturized trees grown in containers to decorate their homes and gardens.<ref>[http://www.arboretum.harvard.edu/plants/bonsai/intro.html "Early American Bonsai: The Larz Anderson Collection of the Arnold Arboretum" by Peter Del Tredici, published in ''Arnoldia'' (Summer 1989) by Harvard University]</ref> |

||

During the [[Tokugawa period]], landscape gardening attained new importance. Cultivation of plants such as [[azaleas|azalea]] and [[maple]]s became a pastime of the wealthy. Growing dwarf plants in containers was also popular. Around 1800, the Japanese changed the term they used for this art to their pronunciation of the Chinese ''penzai'' with its connotation of a shallower container in which the Japanese could now more successfully style small trees.{{Fact|date=February 2009}} However, Chinese |

During the [[Tokugawa period]], landscape gardening attained new importance. Cultivation of plants such as [[azaleas|azalea]] and [[maple]]s became a pastime of the wealthy. Growing dwarf plants in containers was also popular. Around 1800, the Japanese changed the term they used for this art to their pronunciation of the Chinese ''penzai'' with its connotation of a shallower container in which the Japanese could now more successfully style small trees.{{Fact|date=February 2009}} However, Chinese [[penzai]] is generally referred as [[penjing]], which stands for tray scenery, a term to describe the overall picture associated with the small trees. |

||

The oldest known living bonsai trees are in the collection at Happo-en (a private garden and exclusive restaurant) in Tokyo, Japan, where bonsai are between 400 to 800 years old.{{Fact|date=February 2009}} |

The oldest known living bonsai trees are in the collection at Happo-en (a private garden and exclusive restaurant) in Tokyo, Japan, where bonsai are between 400 to 800 years old.{{Fact|date=February 2009}} |

||

Revision as of 12:30, 17 February 2009

Bonsai (Japanese: 盆栽, (literally "bon planted", where a 'bon' is a tray-like pot typically used in bonsai culture [2] [unreliable source?] ) is the art of aesthetic miniaturization of trees, or of developing woody or semi-woody plants shaped as trees, by growing them in containers. Cultivation includes techniques for shaping, watering, and repotting in various styles of containers.

'Bonsai' is a Japanese pronunciation of the earlier Chinese term penzai (盆栽). The word bonsai is used in the West as an umbrella term for all miniature trees in containers or pots.

History

Container-grown plants, including trees as well as other plants, have a history stretching back at least to the early times of Egyptian culture. [3] Pictorial records from around 4000 BC show trees growing in containers cut into rock. Pharaoh Ramesses III donated gardens consisting of potted olives, date palms, and other plants to hundreds of temples. Pre-Common-Era India used container-grown trees for medicine and food.

The word penzai first appeared in writing in China during the Jin Dynasty, in the period 265AD – 420AD. [4] Over time, the practice developed into new forms in various parts of China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam.

Notably, container-grown trees were popularized in Japan during China's Song Dynasty, a period of cultural growth when the Japanese experienced and adopted their own versions of many mainland practices. At this time, the term for dwarf potted trees was "the bowl's tree" (鉢の木, hachi-no-ki[5]), denoting the use of a deep pot. The c.1300 rhymed prose essay, Rhymeprose on a Miniature Landscape Garden, by the Japanese Zen monk Kokan Shiren, outlines aesthetic principles for bonsai, bonseki and garden architecture itself. At first, the Japanese used miniaturized trees grown in containers to decorate their homes and gardens.[6]

During the Tokugawa period, landscape gardening attained new importance. Cultivation of plants such as azalea and maples became a pastime of the wealthy. Growing dwarf plants in containers was also popular. Around 1800, the Japanese changed the term they used for this art to their pronunciation of the Chinese penzai with its connotation of a shallower container in which the Japanese could now more successfully style small trees.[citation needed] However, Chinese penzai is generally referred as penjing, which stands for tray scenery, a term to describe the overall picture associated with the small trees.

The oldest known living bonsai trees are in the collection at Happo-en (a private garden and exclusive restaurant) in Tokyo, Japan, where bonsai are between 400 to 800 years old.[citation needed]

Cultivation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2009) |

Bonsai are not necessarily genetically dwarfed plants. They can be created from nearly any perennial woody-stemmed tree or shrub species which produces true branches and remains small through pot confinement with crown and root pruning. Some species are more sought after for use as bonsai material, because they have characteristics, such as small leaves or needles, that make them appropriate for the smaller design scope of bonsai. The purposes of bonsai are primarily contemplation (for the viewer) and the pleasant exercise of effort and ingenuity (for the grower). By contrast with other plant-related practices, bonsai is not intended for production of food (although some fruit trees can be used as bonsai bearing limited amounts of seasonal fruit), for medicine (although some woody herbs can be made into bonsai), or for creating yard-sized or park-sized landscapes. As a result, the scope of bonsai practice is narrow and focused on the successful long-term cultivation and shaping of one or more small trees in a single pot.

Techniques

The practice of bonsai incorporates a number of techniques either unique to bonsai or, if used in other forms of cultivation, applied in unusual ways that are particularly suitable to the bonsai domain.

Leaf trimming: This technique involves the selective removal of leaves (for most varieties of deciduous tree) or needles (for coniferous trees and some others) from a bonsai's trunk and branches. A common esthetic technique in bonsai design is to expose the tree's branches below groups of leaves or needles (sometimes called "pads"). In many species, particularly coniferous ones, this means that leaves or needles projecting below their branches must be trimmed off. For some coniferous varieties, such as spruce, branches carry needles from the trunk to the tip and many of these needles may be trimmed to expose the branch shape and bark. Needle and bud trimming can also be used in coniferous trees to force back-budding or budding on old wood, which may not occur naturally in many conifers.[7] Along with pruning, leaf trimming is the most common activity used for bonsai development and maintenance, and the one that occurs most frequently during the year.

Pruning: The small size of the tree and some dwarfing of foliage result from pruning the trunk, branches, and roots. Improper pruning can weaken or kill trees.[8] Careful pruning throughout the tree's life is necessary, however, to maintain a bonsai's basic design, which can otherwise disappear behind the uncontrolled natural growth of branches and leaves.

Wiring: Wrapping copper or aluminium wire around branches and trunks allows the bonsai designer to create the desired general form and make detailed branch and leaf placements. When wire is used on new branches or shoots, it holds the branches in place until they lignify (convert into wood), usually 6–9 months or one growing season. Wires are also used to connect a branch to another object (e.g., another branch, the pot itself) so that tightening the wire applies force to the branch. Some species do not lignify strongly, and some specimens' branches are too stiff or brittle to be bent easily. These cases are not conducive to wiring, and shaping them is accomplished primarily through pruning.

Clamping: For larger specimens, or species with stiffer wood, bonsai artists also use mechanical devices for shaping trunks and branches. The most common are screw-based clamps, which can straighten or bend a part of the bonsai using much greater force than wiring can supply. To prevent damage to the tree, the clamps are tightened a little at a time and make their changes over a period of months or years.

Grafting: In this technique, new growing material (typically a bud, branch, or root) is introduced to a prepared area on the trunk or under the bark of the tree. There are two major purposes for grafting in bonsai. First, a number of favorite species do not thrive as bonsai on their natural root stock and their trunks are often grafted onto hardier root stock. Examples include Japanese red maple and Japanese black pine.[7] Second, grafting allows the bonsai artist to add branches (and sometimes roots) where they are needed to improve or complete a bonsai design.[9][10] There are many applicable grafting techniques, none unique to bonsai, including branch grafting, bud grafting, thread grafting, and others.

Defoliation: Short-term dwarfing of foliage can be accomplished in certain deciduous bonsai by partial or total defoliation of the plant partway through the growing season. Not all species can survive this technique. In defoliating a healthy tree of a suitable species, most or all of the leaves are removed by clipping partway along each leaf's petiole (the thin stem that connects a leaf to its branch). Petioles later dry up and drop off or are manually removed once dry. The tree responds by producing a fresh crop of leaves. The new leaves are generally much smaller than those from the first crop, sometimes as small as half the length and width. If the bonsai is shown at this time, the smaller leaves contribute greatly to the bonsai esthetic of dwarfing. This change in leaf size is usually not permanent, and the leaves of the following spring will often be the normal size. Defoliation weakens the tree and should not be performed in two consecutive years.[11]

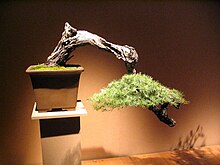

Deadwood: Bonsai growers use deadwood bonsai techniques called jin and shari to simulate age and maturity in a bonsai. Jin is the term used when the bark from an entire branch is removed to create the impression of a snag of deadwood. Shari denotes stripping bark from areas of the trunk to simulate natural scarring from a broken limb or lightning strike. In addition to stripping bark, this technique may also involve the use of tools to scar the deadwood or to raise its grain, and the application of chemicals (usually lime sulfur) to bleach and preserve the exposed deadwood.

Care

Watering

With limited space in a bonsai pot, regular attention is needed to ensure the tree is correctly watered. Sun, heat and wind exposure can dry bonsai trees to the point of drought in a short period of time. While some species can handle periods of relative dryness, others require near-constant moisture. Watering too frequently, or allowing the soil to remain soggy, promotes fungal infections and root rot. Free draining soil is used to prevent waterlogging. Deciduous trees are more at risk of dehydration and will wilt as the soil dries out. Evergreen trees, which tend to cope with dry conditions better, do not display signs of the problem until after damage has occurred.

Repotting

Bonsai are repotted and root-pruned at intervals dictated by the vigour and age of each tree. In the case of deciduous trees, this is done as the tree is leaving its dormant period, generally around springtime. Bonsai are often repotted while in development, and less often as they become more mature. This prevents them from becoming pot-bound and encourages the growth of new feeder roots, allowing the tree to absorb moisture more efficiently.

Pre-bonsai material known as potensai, are often placed in "growing boxes" which are made from scraps of fenceboard or wood slats. These large boxes allow the roots to grow more freely and increase the vigor of the tree. The second stage, after using a grow box, has been to replant the tree in a "training box;" this is often smaller and helps to create a smaller dense root mass which can be more easily moved into a final presentation pot.

Tools

Special tools are available for the maintenance of bonsai. The most common tool is the concave cutter (5th from left in picture), a tool designed to prune flush, without leaving a stub. Other tools include branch bending jacks, wire pliers and shears of different proportions for performing detail and rough shaping.

Soil and fertilization

Opinions about soil mixes and fertilization vary widely among practitioners. Some promote the use of organic fertilizers to augment an essentially inorganic soil mix, while others will use chemical fertilizers freely. Most use the general rule of little and often due to the flushing effect when watering, taking care to use the correct fertilizer at any given time in each season, depending on the tree's requirements. Bonsai soil is primarily a loose, fast-draining mix of components,[12] often a base mixture of coarse sand or gravel, fired clay pellets or expanded shale combined with an organic component such as peat or bark. In Japan, volcanic soils based on clay are preferred, such as akadama, or "red ball" soil, and kanuma, a type of yellow pumice used for azaleas and other calcifuges.

Location and overwintering

Bonsai are sometimes marketed or promoted as house plants, but few of the traditional bonsai species can thrive or even survive inside a typical house. The best guideline to identifying a suitable location for a bonsai is its native hardiness. If the bonsai grower can closely replicate the full year's temperature, humidity, and sunlight, the bonsai should do well. In practice, this means that trees from a hardiness zone closely matching the grower's location will generally be the easiest to grow, and others will require more work or will not be viable at all. [13]

Outdoors

Most bonsai species are outdoor trees and shrubs by nature, and they require temperature, humidity, and sunlight conditions approximating their native climate year round. The skill of the gardener can help plants from outside the local hardiness zone to survive and even thrive, but doing so takes careful watering, shielding of selected bonsai from excessive sunlight or wind, and possibly protection from winter conditions (e.g., through the use of cold boxes or winter greenhouses).

Traditional bonsai species (particularly those from the Japanese tradition) are temperate climate trees, and require moderate temperatures, moderate humidity, and full sun in summer with a dormancy period in winter that may need be near freezing. They do not thrive indoors, where the light is generally too dim, and humidity often too low, for them to grow properly. Only in the dormant period can they safely be brought indoors, and even then the plants require cold temperatures and lighting that approximates the number of hours the sun is visible. Raising the temperature or providing more hours of light than available from natural daylight can cause the bonsai to break dormancy, which often weakens or kills it.

Indoors

Tropical and Mediterranean species typically require consistent temperatures close to room temperature, and with correct lighting and humidity many species can be kept indoors all year. Those from cooler climates may benefit from a winter dormancy period, but temperatures need not be dropped as far as for the temperate climate plants and a north-facing windowsill or open window may provide the right conditions for a few winter months. [14]

Containers

Containers come in a variety of shapes and colors, and may be glazed or unglazed. Containers with straight sides and sharp corners are generally better suited to formally presented plants, while oval or round containers might be used for plants with informal shapes. Most evergreen bonsai are placed in unglazed pots, while deciduous trees are planted in glazed pots. The color of the pot should complement the tree, and many formal and informal rules guide the selection of pot finish and color for a particular tree. Pots are also distinguished by their size. The design of the bonsai tree, the thickness of its trunk, and its height can all be considered when determining the size of of a suitable pot.

Some pots are highly collectible, like ancient Chinese or Japanese pots made in regions with experienced pot makers such as Tokoname, Japan or Yixing, China. Today many western potters throughout Europe and the United States produce fine quality pots for Bonsai.

Unlike many common plant containers, bonsai pots have drainage holes to allow excess water to drain. The grower usually covers the holes with a plastic screen or mesh to prevent soil from escaping and pests from entering the pots from below.

Common styles

In English, the most common styles include: formal upright, slant, informal upright, cascade, semi-cascade, raft, literati, and group/forest.

- The formal upright style, or Chokkan, is characterized by a straight, upright, tapering trunk. The trunk and branches of the informal upright style, or Moyogi, may incorporate pronounced bends and curves, but the apex of the informal upright is always located directly over where the trunk begins at the soil line.

- Slant-style, or Shakan, bonsai possess straight trunks like those of bonsai grown in the formal upright style. However, the slant style trunk emerges from the soil at an angle, and the apex of the bonsai will be located to the left or right of the root base.

- Cascade-style, or Kengai, bonsai are modeled after trees which grow over water or on the sides of mountains. The apex, or tip of the tree in the Semi-cascade-style, or Han Kengai, bonsai extend just at or beneath the lip of the bonsai pot; the apex of a (full) cascade style falls below the base of the pot.

- Raft-style, or Netsuranari, bonsai mimic a natural phenomenon that occurs when a tree topples onto its side (typically due to erosion or another natural force) and branches along the exposed side of the trunk, growing as if they are a group of new trunks. Sometimes, roots will develop from buried portions of the trunk. Raft-style bonsai can have sinuous, straight-line, or slanting trunks, all giving the illusion that they are a group of separate trees -- while actually being the branches of a tree planted on its side.

- The literati style, or Bunjin-gi, bonsai is characterized by a generally bare trunk line, with branches reduced to a minimum, and typically placed higher up on a long, often contorted trunk. This style derives its name from the Chinese literati, who were often artists, and some of whom painted Chinese brush paintings, like those found in the ancient text, The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, depicting pine trees that grew in harsh climates, struggling to reach sunlight. In Japan, the literati style is known as bunjin-gi (文人木[15]). (Bunjin is a translation of the Chinese phrase wenren meaning "scholars practiced in the arts" and gi is a derivative of the Japanese word, ki, for "tree").

- The group or forest style, or Yose Ue, comprises a planting of more than one tree (typically an odd number if there are three or more trees, and essentially never 4 because of its significance in China) in a bonsai pot. The trees are usually the same species, with a variety of heights employed to add visual interest and to reflect the age differences encountered in mature forests.

- The root-over-rock style, or Sekijoju, is a style in which the roots of a tree (typically a fig tree) are wrapped around a rock. The rock is at the base of the trunk, with the roots exposed to varying degrees.

- The broom style, or Hokidachi is employed for trees with extensive, fine branching, often with species like elms. The trunk is straight and upright. It branches out in all directions about 1/3 of the way up the entire height of the tree. The branches and leaves form a ball-shaped crown which can also be very beautiful during the winter months.

- The multi-trunk style, or Ikadabuki has all the trunks growing out of one root system, and it actually is one single tree. All the trunks form one crown of leaves, in which the thickest and most developed trunk forms the top.

- The growing-in-a-rock, or Ishizuke style means the roots of the tree are growing in the cracks and holes of the rock. There is not much room for the roots to develop and take up nutrients. These trees are designed to visually represent that the tree has to struggle to survive.

Size classifications

| Class | Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm | in | |||

| tiny | Mame | Keshi-tsubu | up to 2.5 | up to 1 |

| Shito | 2.5 – 7.5 | 1–3 | ||

| small | Shohin | Gafu | 13 – 20 | 5–8 |

| Komono | up to 18 | up to 7.2 | ||

| Myabi | 15–25 | 6–10 | ||

| medium | Kifu | Katade-mochi | up to 40 | 16 |

| medium to large | Chu/Chuhin | 40–60 | 16–24 | |

| large | Dai/Daiza | Omono | up to 120 | up to 48 |

| Bonju | over 100 | over 40 | ||

Not all sources agree on exact range of size ranges. There are a number of specific techniques and styles associated with mame and shito sizes, the smallest bonsai.

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Indoor bonsai. (Discuss) |

Collecting

Bonsai may be developed from material obtained at gardening centers, or from material collected from a wild or urban landscape. Mature landscape plants which are being discarded from a site can provide excellent material for bonsai. Some regions have plant material that is known for its suitability in form - for example the California Juniper and Sierra Juniper found in the Sierra Mountains, the Ponderosa pine found in the Rocky Mountains, and the Bald Cypress found in the swamps of the Everglades.

References

- ^ William N. Valavanis, "The History of Goshin (Protector of the spirit)", North American Bonsai Federation Newsletter #1, Feature #5 (December 2002). Accessed April 1, 2008.

- ^ http://www.phoenixbonsai.com/Terms/Bonsai.html

- ^ Koreshoff, Deborah R. (1984). Bonsai: Its Art, Science, History and Philosophy. Timber Press, Inc. ISBN 0-88192-389-3.

- ^ Liang, Amy (2005). The Living Art of Bonsai: Principles and Techniques of Cultivation and Propagation. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 1-4027-1901-9.

- ^ http://www.phoenixbonsai.com/Terms/Hachinoki.html

- ^ "Early American Bonsai: The Larz Anderson Collection of the Arnold Arboretum" by Peter Del Tredici, published in Arnoldia (Summer 1989) by Harvard University

- ^ a b Adams, Peter D. (1981). The Art of Bonsai. Ward Lock Ltd. ISBN 0-7063-7116.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Lewis, Colin (2003). The Bonsai Handbook. Advanced Marketing Ltd. ISBN 1-903938-30-9.

- ^ http://www.bonsaikc.com/grafting1.htm "Grafting as a Bonsai Tool"

- ^ http://www.evergreengardenworks.com/rootgraf.htm "Root Grafts for Bonsai"

- ^ Norman, Ken (2005). Growing Bonsai: A Practical Encyclopedia. Lorenz Books. ISBN 9-780754-815723.

- ^ It's All In The Soil by Mike Smith, published in Norfolk Bonsai (Spring 2007) by Norfolk Bonsai Association

- ^ Pike, Dave (1989). Indoor Bonsai. The Crowood Press. ISBN 9-781852-232542.

- ^ Lesniewicz, Paul (1996). Bonsai in Your Home. Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8069-0781-9.

- ^ http://www.phoenixbonsai.com/Terms/bunjingi.html

See also

- Bonsai aesthetics

- Penjing — Chinese precursor to bonsai

- Saikei — gardens using bonsai

- Niwaki — Japanese art of tree pruning

- Mambonsai — pop culture twist on bonsai

- Indoor bonsai

- Topiary — western art of tree pruning

- List of organic gardening and farming topics

- List of species used in bonsai

- List of bonsai on stamps

- Deadwood Bonsai Techniques

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA