Medea: Difference between revisions

m minor grammar |

m →Medea in popular culture: Woody Allen had his character, Alvy Singer in the movie "Annie Hall," use the Medea reference in revealing his jealousy of Annie. |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

* "Medea--One Foot In Hell" is the final track on [[The Showdown]]'s album [[Back Breaker]]. |

* "Medea--One Foot In Hell" is the final track on [[The Showdown]]'s album [[Back Breaker]]. |

||

* In James Owen's novel "The Search for the Red Dragon," Medea is a woman that lives on only as a reflection in a mirror. She spends most of her time in the novel talking to [[Peter Pan]] in a cave guarded by children dressed in animal furs. |

* In James Owen's novel "The Search for the Red Dragon," Medea is a woman that lives on only as a reflection in a mirror. She spends most of her time in the novel talking to [[Peter Pan]] in a cave guarded by children dressed in animal furs. |

||

* In the Woody Allen Movie "Annie Hall", the character played by him, Alvy Singer, is lamenting Annie moving to Hollywood. Leaving a theater in an impromtu conversation with an older lady he meets on the street, she asks him, "Don't tell me you're jealous?" Alvy replies, "Yeah. Jealous? A little bit. Like Medea." |

|||

====Primary sources==== |

====Primary sources==== |

||

Revision as of 19:53, 5 June 2009

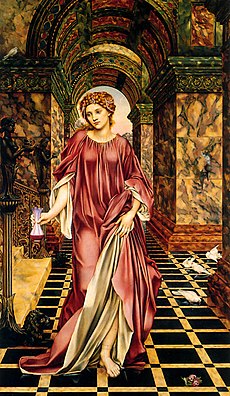

Medea (Greek: Μήδεια, Mēdeia) is a woman in Greek mythology. She was the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, niece of Circe, granddaughter of the sun god Helios, and later wife to the hero Jason, with whom she had two children: Mermeros and Pheres. In Euripides' play Medea, Jason leaves Medea when Creon, king of Corinth, offers him his daughter, Creusa or Glauce. The play tells of how Medea gets her revenge on her husband for this betrayal.

The myths involving Jason also involve Medea. These have been interpreted by specialists, principally in the past, as part of a class of myths that tell how the Hellenes of the distant heroic age, before the Trojan War, faced the challenges of the pre-Greek "Pelasgian" cultures of mainland Greece, the Aegean and Anatolia. Jason, Perseus, Theseus, and above all Heracles, are all "liminal" figures, poised on the threshold between the old world of shamans, chthonic earth deities, and the new Bronze Age Greek ways.

Medea figures in the myth of Jason and the Argonauts, a myth known best from a late literary version worked up by Apollonius of Rhodes in the 3rd century B.C. and called the Argonautica. But for all its self-consciousness and researched archaic vocabulary, the late epic was based on very old, scattered materials.

Medea is known in most stories as an enchantress and is often depicted as being a priestess of the goddess Hecate or a witch. The myth of Jason and Medea is very old, originally written around the time Hesiod wrote the Theogony. It was known to the composer of the Little Iliad, part of the Epic Cycle.

The myth of Jason and Medea

Medea's role began after Jason arrived from Iolcus to Colchis to claim his inheritance and throne by retrieving the Golden Fleece. Medea fell in love with him and promised to help him, but only on the condition that if he succeeded, he would take her with him and marry her. Jason agreed. In a familiar mythic motif, Aeëtes promised to give him the fleece, but only if he could perform certain tasks. First, Jason had to plough a field with fire-breathing oxen that he had to yoke himself. Medea gave him a potion to protect him from the bulls' fiery breath. Then, Jason had to sow the teeth of a dragon in the ploughed field (compare the myth of Cadmus). The teeth sprouted into an army of warriors. Jason was forewarned by Medea, however, and knew to throw a rock into the crowd. Unable to determine where the rock had come from, the soldiers attacked and defeated each other. Finally, Aeëtes made Jason fight and kill the sleepless dragon that guarded the fleece. Medea put the beast to sleep with her narcotic herbs. Jason then took the fleece and sailed away with Medea, as he had promised. (Some accounts say that Medea only helped Jason in the first place because Hera had convinced Aphrodite or Eros to cause Medea to fall in love with him.) Medea distracted her father as they fled by killing her brother Absyrtus. In some versions, Medea is said to have dismembered his body and scattered his parts on an island, knowing her father would stop to retrieve them for proper burial; in other versions, it is Absyrtus himself who pursued them, and was killed by Jason. During the fight, Atalanta was seriously wounded, but Medea healed her.

According to some versions, Medea and Jason stopped on her aunt Circe's island so that she could be cleansed after the murder of her brother, relieving her of blame for the deed.

On the way back to Thessaly, Medea prophesied that Euphemus, the Argo's helmsman, would one day rule over all Libya. This came true through Battus, a descendant of Euphemus.

The Argo then reached the island of Crete, guarded by the bronze man, Talos (Talus). Talos had one vein which went from his neck to his ankle, bound shut by a single bronze nail. According to Apollodorus, Talos was slain either when Medea drove him mad with drugs, deceived him that she would make him immortal by removing the nail, or was killed by Poeas's arrow (Apollodorus 1.140). In the Argonautica, Medea hypnotized him from the Argo, driving him mad so that he dislodged the nail, ichor flowed from the wound, and he bled to death (Argonautica 4.1638). After Talos died, the Argo landed.

While Jason searched for the Golden Fleece, Hera, who was still angry at Pelias, conspired to make him fall in love with Medea, who she hoped would kill Pelias. When Jason and Medea returned to Iolcus, Pelias still refused to give up his throne. Medea conspired to have Pelias' own daughters kill him. She told them she could turn an old ram into a young ram by cutting up the old ram and boiling it (alternatively, she did this with Aeson, Jason's father). During the demonstration, a live, young ram jumped out of the pot. Excited, the girls cut their father into pieces and threw them into a pot. Having killed Pelias, Jason and Medea fled to Corinth.

Many endings

In Corinth, Jason left Medea for the king's daughter. Medea took her revenge by sending Glauce a dress and golden coronet, covered in poison. This resulted in the deaths of both the princess and the king, Creon, when he went to save her. Then Medea stabbed to death the two sons she bore Jason. Afterward, she left Corinth and flew to Athens in a golden chariot driven by dragons sent by her grandfather Helios, god of the sun.

The tragic situation of Medea, abandoned in Corinth by Jason, was the subject matter transformed by Euripides in his tragedy Medea, first performed in 431 BC. In this telling, Medea resorted to filicide before her flight to Athens. Euripides was revolutionary in his retelling of Medea's myth because he was the first one to show that she hadn't killed her children because she was mad or a barbarian, but because she was extremely distressed and furious at Jason for leaving her to marry a princess.[citation needed] Fueled by a need for revenge, she sent Glauce a poisoned dress and crown that burned her to death. Creon found her corpse and clutched it in mourning, crying, "Let me die as well." The dress was poisoned so as to kill anyone who touched the girl. It killed him as well. After some hesitation and self-debate, Medea then killed her two sons, Mermeros and Pheres, to protect them from the King's guards, who would have murdered them in a more painful and torturous fashion.

Fleeing from Jason, Medea made her way to Thebes where she healed Heracles (the former Argonaut) for the murder of Iphitus. In return, Heracles gave her a place to stay in Thebes until the Thebans drove her out in anger, despite Heracles' protests.

She then fled to Athens where she met and married Aegeus. They had one son, Medus, although Hesiod makes Medus the son of Jason[1]. Her domestic bliss was once again shattered by the arrival of Aegeus' long-lost son, Theseus. Determined to preserve her own son's inheritance, Medea convinced her husband that Theseus was a threat and that he should be disposed of. As Medea handed Theseus a cup of poison, Aegeus recognized the young man's sword as his own, which he had left behind many years previous for his newborn son, to be given to him when he came of age. Knocking the cup from Medea's hand, Aegeus embraced Theseus as his own.

Medea then returned to Colchis and, finding that Aeëtes had been deposed by his brother, promptly killed her uncle, and restored the kingdom to her father. Herodotus reports another version, in which Medea and her son Medus fled from Athens to the Iranian plateau and lived among the Aryans, who then changed their name to the Medes.[2]

Personae of Medea

Confusion and frustration may arise if modern readers attempt to shoehorn the disparate mythic elements connected with the persona of Medea into a single, self-consistent historicized narrative, in order to produce a "biography" in the hagiographic manner familiar to Christians. Though the early literary presentations of Medea are lost,[3] Apollonius of Rhodes, in a redefinition of epic formulas, and Euripides, in a dramatic version for a specifically Athenian audience, each employed the figure of Medea; Seneca offered yet another tragic Medea, of witchcraft and potions, and Ovid rendered her portrait three times for a sophisticated and sceptical audience in Imperial Rome. The far-from-static evolution undergone by the figure of Medea was the subject of a recent set of essays published in 1997.[4] Other, non-literary traditions guided the vase-painters,[5] and a localized, chthonic presence of Medea was propitiated with unrecorded emotional overtones at Corinth, at the sanctuary devoted to her slain children,[6] or locally venerated elsewhere as a foundress of cities.[7]

Music

- Francesco Cavalli Giasone (opera, 1649)

- Antonio Caldara "Medea in Corinto" (cantata for alto, 2 violins and basso continuo, 1711) An excerpt can be listened to at http://www.earlymusic.net/jaycarter/audiovideo.htm

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier Médée (tragédie en musique,1693)

- Georg Anton Benda composed the melodrama Medea in 1775 on a text by Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter.

- Luigi Cherubini composed the opera Médée in 1797 and it is Cherubini's best-known work, but better known by its Italian title, Medea.

- Saverio Mercadante composed his opera Medea in 1851 to a libretto by Salvatore Cammarano.

- Darius Milhaud composed the opera Médée in 1939 to a text by Madeleine Milhaud (his wife and cousin).

- American composer Samuel Barber wrote his Medea ballet (later re-named The Cave of the Heart) in 1947 for Martha Graham and derived from that Medea's Meditation & Dance of Vengeance Op. 23a in 1955. The musical Blast! uses an arrangement of Barber's Medea as their end to Act I.

- Star of Indiana—the drum and bugle corps that Blast! formed out of—used Parados, Kantikos Agonias, and Dance of Vengeance in their 1993 production (with Bartok's Allegro from Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste), between Kantikos and Vengeance.

- In 1993 Chamber Made produced an opera Medea composed by Gordon Kerry, with text by Justin Macdonnell after Seneca.

- Michael John LaChiusa scored "Marie Christine," a Broadway musical with heavy opera influence based on the story of Medea. The production premiered at the Vivian Beaumont Theater in December 1999 for a limited run under Lincoln Center Theatre. LaChuisa's score and book were nominated for a Tony Award in 2000, as was a tour-de-force performance by three-time Tony winner Audra McDonald.

- In 1991, the world premiere was held in the Teatro Arriaga, Bilbao of the opera Medea by Mikis Theodorakis. This was the first in Theodorakis' trilogy of lyrical tragedies, the others being Electra and Antigone.

- Rockettothesky medea 2008

- instrumental chamber music piece Medea by Dietmar Bonnen 2008

Cinema and television

- In the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts, Medea was portrayed by Nancy Kovack.

- In the 2000 Hallmark presentation Jason and the Argonauts, Medea was portrayed by Jolene Blalock.

- In 1970, the Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini directed a film adaptation of Medea featuring the opera singer Maria Callas in the title role.

- In 1978, the film A Dream of Passion in which Melina Mercouri as an actress portraying Medea seeks out Ellen Burstyn a mother who recently murdered her children.

- In 1987, director Lars von Trier filmed his pre-Dogma 95 Medea for Danish television, using a preexisting script by film maker Carl Theodor Dreyer. Cast included Udo Kier, Kirsten Olesen, Henning Jensen, Mette Munk Plum.

- In 2007, director Tonino De Bernardi filmed a modern version of the myth, set in Paris and starring Isabelle Huppert as Medea, called Médée Miracle. The character of Medea lives in Paris with Jason, who leaves her.

Medea in popular culture

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (September 2008) |

- A "Medea complex" is sometimes used to describe parents who murder or otherwise harm their children.[8]

- Born Susie Benjamin, Medea Benjamin, co-founder of both Code Pink and the international human rights organization Global Exchange, renamed herself after the Greek mythological character Medea during her freshman year at Tufts University.

- Medea is featured in the visual novel game and anime series Fate/stay night as an example of the Caster-class Servant.

- In 2006 The Abingdon Theatre Company produced a spoof on the Medea novels, "My Deah" by John Epperson.

- Playwright Christopher Durang wrote a short spoof of Medea.

- Playwright Neil LaBute wrote a scene in his play "Bash: Latter-Days Plays" called "Medea Redux", inspired by the myth of Medea.

- Medea is one of the NPC villains in the Freedom City campaign setting for the Mutants and Masterminds role-playing game. Talos, the bronze man of Crete, is also featured as an NPC villain.

- Singer/songwriter Vienna Teng wrote a song entitled My Medea.

- The genetic technique called Maternal effect dominant embryonic arrest, which favors offspring with particular genes, is named after Medea.

- In Stephen Sondheim's musical, "A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum," the opening number, "Comedy Tonight," contains the line, "Nothing that's grim; nothing that's Greek. She plays Medea later this week."

- In the PS2 game Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3, Medea is the Persona for the character Chidori. Appropriate to the "Medea complex", Medea herself tries to strangle Chidori at one point in the game.

- In the PS2 game Dragon Quest VIII: Journey of the Cursed King, Medea is the princess of a ruined kingdom, Trodain. She was put under a curse by a jester named Dhoulmagus and was transformed into a horse. She is a horse throughout most of the game.

- In the book series Cry of the Icemark, book 2, The Blade of Fire, Medea tries to kill her brother and betray her country.

- "Medea--One Foot In Hell" is the final track on The Showdown's album Back Breaker.

- In James Owen's novel "The Search for the Red Dragon," Medea is a woman that lives on only as a reflection in a mirror. She spends most of her time in the novel talking to Peter Pan in a cave guarded by children dressed in animal furs.

- In the Woody Allen Movie "Annie Hall", the character played by him, Alvy Singer, is lamenting Annie moving to Hollywood. Leaving a theater in an impromtu conversation with an older lady he meets on the street, she asks him, "Don't tell me you're jealous?" Alvy replies, "Yeah. Jealous? A little bit. Like Medea."

Primary sources

- Heroides XII

- Metamorphoses VII, 1-450

- Tristia iii.9

- Euripides, Medea

- Hyginus, Fabulae 21-26

- Pindar, Pythian Odes, IIII

- Seneca: Medea (tragedy)

- Apollodorus, Bibliotheke I, 23-28

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus Argonautica (epic)

- Herodotus, Histories VII.62i

- Hesiod, Theogony 1000-2

Translations

- G.Theodoridis. Full Text. Prose: [1]

Secondary material

- Jean Anouilh, Medea

- John Gardner (novelist), Jason and Medeia

- Robinson Jeffers, Medea

- Hans Henny Jahnn, Medea

- Percival Everett, For Her Dark Skin

- Maxwell Anderson, The Wingless Victory

- Geoffrey Chaucer The Legend of Good Women (1386)

- Michael Wood, In Search of Myths & Heroes: Jason and the Golden Fleece

- Chrysanthos Mentis Bostantzoglou (Bost), Medea (parody of Medea of Euripides)

Related Literature

- Medea (Ovid's lost tragedy - two lines are extant)[9]

- Marina Carr, By the Bog of Cats

- A. R. Gurney, The Golden Fleece

- Pierre Corneille Médée (tragedy, 1635)

- Heiner Muller, Medeamaterial and Medeaplay

- William Morris Life and Death of Jason (epic poem, 1867)

- Franz Grillparzer, Das goldene Vliess (The Golden Fleece) (play, 1822)

- Christa Wolf, Medea (a novel) (published in German 1993, translated to English 1998)

- Cherrie Moraga, The Hungry Woman: A Mexican Medea (combines classical Greek myth Medea with Mexicana/o legend of La Llorona and Aztec myth of lunar deity Coyolxauhqui)

- The Medea of the modern times

- Cicero, Pro Caelio (political speech) Cicero refers to Clodia as the Clodia Medea

References

- ^ Hesiod Theogony 1000-2

- ^ Herodotus Histories VII.62i

- ^ The lost Corinthiaca of Naupactos and the Building of the Argo, by Epimenides of Crete, for instances.

- ^ Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy, and Art, James Joseph Clauss and Sarah Iles Johnston, eds., (Princeton University Press) 1997. Includes a bibliography of works focused on Medea.

- ^ As on the bell krater at the Cleveland Museum of Art (91.1) discussed in detail by Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood, "Medea at a Shifting Distance: Images and Euripidean tragedy", in Clauss and Johnston 1997, pp 253-96.

- ^ Edouard Will, Corinth 1955. "By identifying Medea, Ino and Melikertes, Bellerophon, and Hellotis as pre-Olympianprecursors of Hera, Poseidon, and Athena, he could give to Corinth a religious antiquity it did not otherwise possess," wrote Nancy Bookidis, "The Sanctuaries of Corinth", Corinth 20 (2003)

- ^ "Pindar shows her prophesying the foundation of Cyrene; Herodotus makes her the legendary eponymous founder of the Medes; Callimachus and Apollonius describe colonies founded by Colchians originally sent out in pursuit of her" observes Nita Krevans, "Medea as foundation heroine", in Clauss and Johnston 1997 pp 71-82 (p. 71).

- ^ Lucire, Yolande. Medea: Perspectives on a Multicide [online]. Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, The; Volume 25, Issue 2; Dec 1993; 74-82. Availability: <http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=783875560798854;res=E-LIBRARY> ISSN: 0045-0618.

- ^ Fragments are printed and discussed by Theodor Heinze, Der XII. Heroidenbrief: Medea an Jason Mit einer Beilage: Die Fragmente der Tragödie Medea P. Ovidius Naso. (in series Mnemosyne, Supplements, 170. 1997