Apollo 11: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{NPOV}} |

||

{{for|the six-time race-winning horse|Apollo Eleven}} |

{{for|the six-time race-winning horse|Apollo Eleven}} |

||

Revision as of 00:30, 18 June 2009

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

| COSPAR ID | 1969-059A |

|---|---|

| SATCAT no. | 04039 |

| Mission duration | 8 d 03 h 18 m 35 s |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | July 16, 1969 13:32:00 UTC |

| |

The Apollo 11 mission was the first manned mission to land on the Moon. It was the fifth human spaceflight of Project Apollo and the third human voyage to the Moon. It was also the second all-veteran crew in manned spaceflight history. Launched on July 16, 1969, it carried Mission Commander Neil Alden Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin Eugene 'Buzz' Aldrin, Jr. On July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin became the first humans to land on the Moon, while Collins orbited above.

The mission fulfilled President John F. Kennedy's goal of reaching the moon by the end of the 1960s, which he expressed during a speech given before a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961:[2]

"I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth."

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Neil Armstrong Second spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot | Michael Collins Second spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. Second spaceflight | |

Each crewmember had made a spaceflight before this mission. Collins was originally slated to be the Command Module Pilot (CMP) on Apollo 8 but was removed when he required surgery on his back and was replaced by Jim Lovell, his backup for that flight. After Collins was medically cleared he took what would have been Lovell's spot on Apollo 11.

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | James A. Lovell, Jr | |

| Command Module Pilot | William A. Anders | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Fred W. Haise, Jr | |

In the spring of 1969 Bill Anders accepted a job with the National Space Council effective in August 1969 and had announced his retirement as an astronaut. At that point Ken Mattingly was moved from the support crew into parallel training with Anders as backup Command Module Pilot in case Apollo 11 was delayed past its intended July launch (at which point Anders would be unavailable if needed) and would later join Lovell's crew and ultimately be assigned as the original Apollo 13 CMP.[3]

Support crew

- Charles Moss Duke, Jr., Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM)

- Ronald Evans, CAPCOM

- Owen K. Garriott, CAPCOM

- Don L. Lind, CAPCOM

- Ken Mattingly, CAPCOM

- Bruce McCandless II, CAPCOM

- Harrison Schmitt, CAPCOM

- Bill Pogue

- Jack Swigert

Flight directors

- Cliff Charlesworth, launch and EVA

- Gene Kranz, lunar landing

- Glynn Lunney, lunar ascent

Nomenclature

The lunar module was named Eagle after the bald eagle depicted on the insignia; the bald eagle is the national bird of the United States. The command module was named Columbia, from the traditional feminine name Columbia used for the United States in song and poetry. The name may also have been chosen in reference to the columbiad cannon used to launch the moonships in Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon. Some internal NASA planning documents referred to the call signs as Snowcone and Haystack,[4] but these were quietly changed before being announced to the press.

Mission highlights

Launch and lunar landing

In addition to throngs of people crowding highways and beaches near the launch site, millions watched the event on television, with NASA Chief of Public Information Jack King providing commentary. President Richard Nixon viewed the proceedings from the Oval Office of the White House.

A Saturn V launched Apollo 11 from the Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969 at 13:32 UTC (9:32 a.m. local time). It entered orbit 12 minutes later.[1] After one and a half orbits, the S-IVB third-stage engine pushed the spacecraft onto its trajectory toward the Moon with the Trans Lunar Injection burn. About 30 minutes later the command/service module pair separated from this last remaining Saturn V stage and docked with the lunar module still nestled in the Lunar Module Adaptor.

On July 19 Apollo 11 passed behind the Moon and fired its service propulsion engine to enter lunar orbit. In the thirty orbits[5] that followed, the crew saw passing views of their landing site in the southern Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tranquillitatis) about 20 kilometers (12 mi) southwest of the crater Sabine D (0.67408N, 23.47297E). The landing site was selected in part because it had been characterized as relatively flat and smooth by the automated Ranger 8 and Surveyor 5 landers along with the Lunar Orbiter mapping spacecraft and unlikely to present major landing or extra-vehicular activity (EVA) challenges.[6]

On July 20, 1969 the lunar module (LM) Eagle separated from the command module Columbia. Collins, alone aboard Columbia, inspected Eagle as it pirouetted before him to ensure the craft was not damaged.

As the descent began, Armstrong and Aldrin found that they were passing landmarks on the surface 4 seconds early and reported they were "long". They would land miles west of their target point. The LM navigation and guidance computer distracted the crew with several unusual program alarms. Inside Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, computer engineer Jack Garman told guidance officer Steve Bales it was safe to continue the descent and this was relayed to the crew. When Armstrong again looked outside, he saw that the computer's landing target was in a boulder strewn area just north and east of a 400 meter diameter crater (later determined to be "West crater", named for its location in the western part of the originally planned landing ellipse). Armstrong took semi-automatic control[7] and with Aldrin calling out altitude and velocity data, landed at 20:17 UTC on July 20 with about 25 seconds of fuel left.[8]

The program alarms were called executive overflows, during which the computer could not process all of its tasks in real time and had to postpone some of them.[9] This was neither a computer error nor an astronaut error, but stemmed from a mistake in how the astronauts had been trained. Although unneeded for the landing, the rendezvous radar was intentionally turned on to make ready for a fast abort. Ground simulation setups had not foreseen that a fast stream of spurious interrupts from this radar could happen, depending upon how the hardware randomly powered up before the LM then began nearing the lunar surface: Hence the computer had to deal with data from two radars, not the landing radar alone, which led to the overload.[10][11][12]

Although Apollo 11 landed with less fuel than other missions, they also encountered a premature low fuel warning. It was later found to be caused by the lunar gravity permitting greater propellant 'slosh' which had uncovered a fuel sensor. On future missions extra baffles were added to the tanks.[8]

Buzz Aldrin spoke the first words (albeit technical jargon) from the LM on the lunar surface. Throughout the descent Aldrin had called out navigation data to Armstrong, who was busy piloting the LM. As Eagle landed Aldrin said, "Contact light! Okay, engine stop. ACA - out of detent." Armstrong acknowledged "Out of detent" and Aldrin continued, "Mode control - both auto. Descent engine command override off. Engine arm - off. 413 is in."

Then Armstrong said the famous words, "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." Armstrong's abrupt change of call sign from "Eagle" to "Tranquility Base" caused momentary confusion at Mission Control. Charles Duke, acting as CAPCOM during the landing phase, acknowledged their landing, expressing the relief of Mission Control after the unexpectedly drawn-out descent.[8]

Shortly after landing, before preparations began for the EVA, Aldrin broadcast that:

This is the LM pilot. I'd like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.[13]

He then took Communion privately. At this time NASA was still fighting a lawsuit brought by atheist Madalyn Murray O'Hair (who had objected to the Apollo 8 crew reading from the Book of Genesis) which demanded that their astronauts refrain from religious activities while in space. As such, Aldrin chose to refrain from directly mentioning this. He had kept the plan quiet (not even mentioning it to his wife) and did not reveal it publicly for several years. Buzz Aldrin was an elder at Webster Presbyterian Church in Webster, TX. His communion kit was prepared by the pastor of the church, the Rev. Dean Woodruff. Aldrin described communion on the moon and the involvement of his church and pastor in the October, 1970 edition of Guideposts magazine and in his book "Return to Earth." Webster Presbyterian possesses the chalice used on the moon, and commemorates the Lunar Communion each year on the Sunday closest to July 20.[14]

Lunar surface operations

- See also: Neil Armstrong — First Moon walk

At 02:56 UTC on July 21 (10:56pm EDT, July 20), 1969, Armstrong made his descent to the Moon's surface and spoke his famous line "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind"[15][16][17][18][19] exactly six and a half hours after landing.[1] Aldrin joined him, describing the view as "Magnificent desolation."[20]

They planned placement of the Early Apollo Scientific Experiment Package (EASEP) and the U.S. flag by studying their landing site through Eagle's twin triangular windows, which gave them a 60° field of view. Preparation required longer than the two hours scheduled. Armstrong initially had some difficulties squeezing through the hatch with his Portable Life Support System (PLSS). According to veteran moonwalker John Young, a redesign of the LM to incorporate a smaller hatch was not followed by a redesign of the PLSS backpack, so some of the highest heart rates recorded from Apollo astronauts occurred during LM egress and ingress.[21][22]

The Remote Control Unit controls on Armstrong's chest kept him from seeing his feet. Climbing down the nine-rung ladder, Armstrong pulled a D-ring to deploy the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA) folded against Eagle's side and activate the TV camera.[23] The first landing used Slow-scan television incompatible with commercial TV, so it was displayed on a special monitor and a conventional TV camera viewed this monitor, significantly losing quality in the process.[24] The signal was received at Goldstone in the USA but with better fidelity by Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station in Australia. Minutes later the feed was switched to the more sensitive Parkes radio telescope in Australia. Despite some technical and weather difficulties, ghostly black and white images of the first lunar EVA were received and broadcast to at least 600 million people on Earth.[25] These original recordings are now missing.

After describing the surface dust ("fine and almost like a powder"[23]), Armstrong stepped off Eagle's footpad and into history as the first human to set foot on another world, famously describing it as "one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."[26] He said that moving in the Moon's gravity, one-sixth of Earth's, was "even perhaps easier than the simulations... It's absolutely no trouble to walk around".[23]

In addition to fulfilling President John F. Kennedy's mandate to land a man on the Moon before the end of the 1960s,[27] Apollo 11 was an engineering test of the Apollo system; therefore, Armstrong snapped photos of the LM so engineers would be able to judge its post-landing condition. He then collected a contingency soil sample using a sample bag on a stick. He folded the bag and tucked it into a pocket on his right thigh. He removed the TV camera from the MESA, made a panoramic sweep, and mounted it on a tripod 12 m (40 ft) from the LM. The TV camera cable remained partly coiled and presented a tripping hazard throughout the EVA.

Aldrin joined him on the surface and tested methods for moving around, including two-footed kangaroo hops. The PLSS backpack created a tendency to tip backwards, but neither astronaut had serious problems maintaining balance. Loping became the preferred method of movement. The astronauts reported that they needed to plan their movements six or seven steps ahead. The fine soil was quite slippery. Aldrin remarked that moving from sunlight into Eagle's shadow produced no temperature change inside the suit, though the helmet was warmer in sunlight, so he felt cooler in shadow.[23]

After the astronauts planted a U.S. flag on the lunar surface, they spoke with President Richard Nixon through a telephone-radio transmission which Nixon called "the most historic phone call ever made from the White House."[28] Nixon originally had a long speech prepared to read during the phone call, but Frank Borman, who was at the White House as a NASA liaison during Apollo 11, convinced Nixon to keep his words brief, out of respect of the lunar landing being Kennedy's legacy.[29]

The MESA failed to provide a stable work platform and was in shadow, slowing work somewhat. As they worked, the moonwalkers kicked up gray dust which soiled the outer part of their suits, the integrated thermal meteoroid garment.

They deployed the EASEP, which included a passive seismograph and a laser ranging retroreflector. Then Armstrong loped about 120 m (400 ft) from the LM to snap photos at the rim of East Crater while Aldrin collected two core tubes. He used the geological hammer to pound in the tubes - the only time the hammer was used on Apollo 11. The astronauts then collected rock samples using scoops and tongs on extension handles. Many of the surface activities took longer than expected, so they had to stop documented sample collection halfway through the allotted 34 min.

During this period Mission Control used a coded phrase to warn Armstrong that his metabolic rates were high and that he should slow down. He was moving rapidly from task to task as time ran out. Rates remained generally lower than expected for both astronauts throughout the walk, however, so Mission Control granted the astronauts a 15-minute extension.[30]

Lunar ascent and return

Aldrin entered Eagle first. With some difficulty the astronauts lifted film and two sample boxes containing more than 22 kg (48 lb) of lunar surface material to the LM hatch using a flat cable pulley device called the Lunar Equipment Conveyor. Armstrong reminded Aldrin of a bag of memorial items in his suit pocket sleeve, and Aldrin tossed the bag down; Armstrong then jumped to the ladder's third rung and climbed into the LM. After transferring to LM life support, the explorers lightened the ascent stage for return to lunar orbit by tossing out their PLSS backpacks, lunar overshoes, one Hasselblad camera, and other equipment. They then repressurised the LM, and settled down to sleep.[31]

While moving in the cabin Aldrin accidentally broke the circuit breaker that armed the main engine for lift off from the moon. There was initial concern this would prevent firing the engine, which would strand them on the moon. Fortunately a felt-tip pen was sufficient to activate the switch.[31] Had this not worked, the Lunar Module circuitry could have been reconfigured to allow firing the ascent engine.[32]

After about seven hours of rest, they were awakened by Houston to prepare for the return flight. Two and a half hours later, at 17:54 UTC, they lifted off in Eagle's ascent stage, carrying 21.5 kilograms of lunar samples with them, to rejoin CMP Michael Collins aboard Columbia in lunar orbit.[1]

After more than 2½ hours on the lunar surface, they had left behind scientific instruments which included a retroreflector array used for the Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment and a Passive Seismic Experiment used to measure moonquakes. They also left an American flag, an Apollo 1 mission patch, and a plaque (mounted on the LM Descent Stage ladder) bearing two drawings of Earth (of the Western and Eastern Hemispheres), an inscription, and signatures of the astronauts and Richard Nixon. The inscription read Here Men From The Planet Earth First Set Foot Upon the Moon, July 1969 A.D. We Came in Peace For All Mankind. They also left behind a memorial bag containing a gold replica of an olive branch as a traditional symbol of peace, the Apollo 1 patch, and a silicon message disk. The disk carries the goodwill statements by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon and messages from leaders of 73 countries around the world. The disc also carries a listing of the leadership of the US Congress, a listing of members of the four committees of the House and Senate responsible for the NASA legislation, and the names of NASA's past and present top management. NASA News Release No. 69-83F (July 13, 1969). (In his 1989 book, Men from Earth, Aldrin says that the items included Soviet medals commemorating Cosmonauts Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin.) Also, according to Deke Slayton's book 'Moonshot', Armstrong carried with him a special diamond-studded Astronaut pin from Deke.

Film taken from the LM Ascent Stage upon liftoff from the moon reveals the American flag, planted some 25 feet (8 m) from the descent stage, whipping violently in the exhaust of the ascent stage engine. Buzz Aldrin witnessed it topple: "The ascent stage of the LM separated ...I was concentrating on the computers, and Neil was studying the attitude indicator, but I looked up long enough to see the flag fall over."[33] Subsequent Apollo missions usually planted the American flags at least 100 feet (30 m) from the LM to avoid being blown over by the ascent engine exhaust.

After rendezvous with Columbia, Eagle's ascent stage was jettisoned into lunar orbit at July 21, 1969 at 23:41 UT (7:41 PM EDT). Just before the Apollo 12 flight, it was noted that Eagle was still likely to be orbiting the moon. Later NASA reports mentioned that Eagle's orbit had decayed resulting in it impacting in an "uncertain location" on the lunar surface.[34] The location is uncertain because the Eagle ascent stage was not tracked after it was jettisoned and the lunar gravity field is sufficiently uncertain to make the orbit of the spacecraft virtually unpredictable after a short time. NASA estimated that the orbit had decayed within months and would have impacted on the Moon.

On July 23, the three astronauts made a television broadcast on the last night before splashdown. Collins commented, "... The Saturn V rocket which put us in orbit is an incredibly complicated piece of machinery, every piece of which worked flawlessly ... We have always had confidence that this equipment will work properly. All this is possible only through the blood, sweat, and tears of a number of a people ...All you see is the three of us, but beneath the surface are thousands and thousands of others, and to all of those, I would like to say, 'Thank you very much.'" Aldrin said, "... This has been far more than three men on a mission to the Moon; more, still, than the efforts of a government and industry team; more, even, than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown ... Personally, in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms comes to mind. 'When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained; What is man that Thou art mindful of him?'" Armstrong concluded, "The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort; next with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; next with four administrations and their Congresses, for implementing that will; and then, with the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft, the Saturn, the Columbia, the Eagle, and the little EMU, the spacesuit and backpack that was our small spacecraft out on the lunar surface. We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft. To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11."[35]

On July 24, the astronauts returned home and were immediately put in quarantine. The splashdown point was 13°19′N 169°9′W / 13.317°N 169.150°W, in the Pacific Ocean 2,660 km (1,440 nm) east of Wake Island, or 380 km (210 nm) south of Johnston Atoll, and 24 km (15 mi) from the recovery ship, USS Hornet. After recovery by helicopter approximately one hour after splashdown,[1] the astronauts were placed in an Airstream trailer that had been designed as a temporary quarantine facility for their transport back to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory. President Richard Nixon was aboard the recovery vessel to personally welcome the astronauts back to Earth.

The astronauts were placed in quarantine after their landing on the moon due to fears that the moon might contain undiscovered pathogens, and that the astronauts may have been exposed to them during their moon walks (this was in accordance with the recently passed Extra-Terrestrial Exposure Law). However, after almost three weeks in confinement (first in their trailer and later in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at the Manned Spacecraft Center), the astronauts were given a clean bill of health.[36] On August 13, 1969, the astronauts exited quarantine to the cheers of the American public. Parades were held in their honor in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles on the same day. A few weeks later, they were invited by Mexico for a parade honoring them in Mexico City.

That evening in Los Angeles there was an official State Dinner to celebrate Apollo 11, attended by Members of Congress, 44 Governors, the Chief Justice, and ambassadors from 83 nations at the Century Plaza Hotel. President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro T. Agnew honored each astronaut with a presentation of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This celebration was the beginning of a 45-day "Giant Leap" tour that brought the astronauts to 25 foreign countries and included visits with prominent leaders such as Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom. Many nations would honor the first manned moon landing by issuing Apollo 11 commemorative postage stamps or coins.[37] Also, a few POWs held in Vietnam received letters from home a few months after the landings with those stamps to covertly let the POWs know that the United States had landed men on the moon.

At the 27th World Science Fiction Convention in St. Louis, Missouri, the three astronauts received a special Hugo award for "the Best Moon Landing Ever."[38]

On September 16, 1969, the three astronauts spoke before a joint session of Congress on Capitol Hill. They presented two U.S. flags, one to the House of Representatives and the other to the Senate, that had been carried to the surface of the moon with them.

Spacecraft location

The command module is displayed at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.. It is placed in the central exhibition hall in front of the Jefferson Drive entrance, and shares the main hall with other pioneering flight vehicles such as the Spirit of St. Louis, the Bell X-1, the North American X-15, Mercury spacecraft Friendship 7, and Gemini 4. The quarantine trailer, the flotation collar, and the righting spheres are displayed at the Smithsonian's Udvar-Hazy Center annex near Washington Dulles International Airport in Virginia.

Mission insignia

The patch of Apollo 11 was designed by Collins, who wanted a symbol for "peaceful lunar landing by the United States". He picked an eagle as the symbol, put an olive branch in its beak, and drew a moon background with the earth in the distance. NASA officials said the talons of the eagle looked too "warlike" and after some discussion, the olive branch was moved to the claws. The crew decided the Roman numeral XI would not be understood in some nations and went with Apollo 11; they decided not to put their names on the patch, so it would "be representative of everyone who had worked toward a lunar landing."[39] All colors are natural, with blue and gold borders around the patch. The LM was named Eagle to match the insignia. When the Eisenhower dollar coin was revived a few years later, the patch design provided the eagle for the back of the coin. The design was kept for the smaller Susan B. Anthony dollar, which was unveiled in 1979, the 10th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission.

See also

- Apollo 11 in popular culture

- Apollo Guidance Computer

- Apollo Moon Landing hoax conspiracy theories

- Extra-vehicular activity

- Google Moon

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

- List of spacewalks and moonwalks

- Splashdown

Photo gallery

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

-

Apollo 11 command module "Columbia".

-

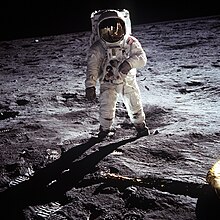

Aldrin stands next to the Passive Seismic Experiment Package with the Lunar Module in the background.

-

Aldrin inspects the LM landing gear.

-

Aldrin unpacks experiments from the LM.

-

Aldrin with the U.S. flag.

-

Panoramic Assembly showing Neil Armstrong.

-

Armstrong on lunar surface with his gold visor raised. From 16 mm film (NASA).

-

Apollo 11 crew members at the White House in 2004.

-

This boilerplate spacecraft was used for recovery training by all Apollo crews. It now displays the flotation bags and collar used during Apollo 11's recovery. Displayed at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

-

Command module, at the National Air and Space Museum

-

View of silicon disc with 73 messages, left by Buzz Aldrin

-

This is a rare early copy of the Lunar Excursion Module Familiarization Manual issued January 15, 1964

References

- ^ a b c d e Richard W. Orloff. "Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference (SP-4029)". NASA.

- ^ "Man on the moon: Kennedy speech ignited the dream" CNN.com

- ^ Donald K. Slayton, "Deke!" (New York: Forge, 1994), 237

- ^ See, e.g., NASA (1969-06-25). "Technical information summary: Apollo 11 (AS-506) Apollo Saturn V space vehicle (TM-X-62812; S/E-ASTR-S-101-69)" (PDF)., p. 8

- ^ Apollo-11 NASA

- ^ NASA (1969-07-06). "Apollo 11 Press Kit (p.1-100)" (PDF). Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Mindell, David A (2008). Digital Apollo. MIT Press. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-0-262-13497-2.

- ^ a b c Jones, Eric M. (editor). "Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal: The First Lunar Landing". NASA.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Michael Collins, in Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, NASA pub. no. SP-350 (1975), chapter 11.4

- ^ "Apollo 11 Mission Report" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ Martin, Fred H. "Apollo 11: 25 Years Later". NASA.

- ^ Don Eyles. "Tales from the Lunar Module Guidance Computer". American Astronautical Society.

- ^ Jones, Eric M. (editor). "Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal: Post-landing Activities". NASA.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Chaikin, Andrew (1998). A Man on the Moon. Penguin Group. pp. 204 & 623. ISBN 0-14-027201-1.

- ^ NASA transcript explains the "a" article was intended, whether or not it was said; without it contrast is drawn between man (the race of humans) and mankind (the race of humans) whereas the intention was to contrast a man (an individual's action) and mankind (as a race).

- ^ NASA Moon landing 35th anniversary includes the "a" article as intended.

- ^ BBC news story on reanalysis which suggests the line was said correctly (with the "a" article).

- ^ BBC news story on later reanalysis which suggests the line was said incorrectly.

- ^ Houston Chronicle coverage of the same story.

- ^ NASA transcript

- ^ Eric M. Jones (2006-04-06). "Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ J.M. Waligora, D.J. Horrigan. "METABOLISM AND HEAT DISSIPATION DURING APOLLO EVA PERIODS - Chapter 4". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Jones, Eric M. (editor). "Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal: One Small Step". NASA.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ *"One giant blunder for mankind: how NASA lost moon pictures".

- ^ "On Eagle's Wings: The [[Parkes Observatory]]'s Support of the Apollo 11 Mission" (PDF). Astronomical Society of Australia. 2001-07-01. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Chaikin, "A Man on the Moon", p. 209 Armstrong forgot to say the word "a" but intended to; according to Chaikin, he wants the phrase to appear in print form with the parenthesized "a".)

- ^ "Apollo 11: 1969 Year in Review, UPI.com"

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration, Apollo 11 and Nixon, March 1996. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ This was related by Frank Borman during the 2008 documentary When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions, part 2.

- ^ Jones, Eric M. (editor). "Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal: EASEP Deployment and Closeout". NASA.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Jones, Eric M. (editor). "Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal: Trying to Rest". NASA.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Murray, Charles & Cox, Catherine (1990). Apollo: Race to the Moon. Touchstone Books. ISBN 0-671-70625-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ National Aeronautics and Space Administration. "NASA Apollo Mission Apollo-11". Kennedy Space Center. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ NASA. "Apollo Tables". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "NASA Apollo Mission Apollo 11". Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ NASA Explores. "NASA Explores... Hirasaki, the NASA engineer quarantined with the Apollo 11 crew". Retrieved November 1, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "Lunar Hall of Fame: Apollo 11 mission".

- ^ "The Long List of Hugo Awards, 1969". New England Science Fiction Association (NESFA). Retrieved 2009-05-28.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Collins, Michael (2001). Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys. Cooper Square Press. pp. 332–333. ISBN 0-8154-1028-X.

Further reading and external links

- Men on the Moon Original reports from The Times

- Cappellari, J.O. Jr. (1972). Where on the Moon? An Apollo Systems Engineering Problem. The Bell System Technical Journal. Volume 51, Number 5.

- Barbour 1969 John Barbour (1969). Footprints on the Moon. Associated Press.

- "One Giant Leap for Mankind: 35th Anniversary of Apollo 11". NASA. 2004. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - NASA Website honoring the mission - Rahman, Tahir (2007). We Came in Peace for all Mankind- the Untold Story of the Apollo 11 Silicon Disc. Leathers Publishing. ISBN 978-1585974412.

- Silicon disc about the size of a half dollar coin etched with 73 messages, left on the moon by Buzz Aldrin.

- Apollo Anniversary: Moon Landing "Inspired World" - National Geographic News, 2004-07-16 - 35th anniversary; Steven Dick, NASA's chief historian: '...a thousand years from now, that step may be considered the crowning achievement of the 20th century.'

- First moon landing in 1969 marked an entire generation - Matt Wallace - Opinion column reminiscing about the Apollo 11 Moon landing and its cultural impact on the 30th anniversary published July 18, 1999 in the (Greensboro, NC) News & Record; "And there was the moon, which was why this was no typical child's summer."

For young readers

- Aldrin, Buzz. Reaching for the Moon. HarperCollins, 2005, 40 pages, ISBN 978-0-060-55445-3

- Thimmesh, Catherine. Team Moon: How 400,000 People Landed Apollo 11 on the Moon. Houghton Mifflin, 2006, 80 pages, ISBN 978-0-618-50757-3

NASA reports

- "Apollo Program Summary Report". NASA. 1975. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - 200+ pages - Ivan D. Ertel; et al. (August 1968-April 1975). "The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology Vol. I-IV". NASA SP-4009. NASA. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - "Apollo 11 Mission Report" (PDF). NASA. 1971. - 200+ pages

- Office of Public Affairs, NASA. "EP-72 Log of Apollo 11". NASA History Office. Retrieved 2006-01-16. - Timeline of the mission

Multimedia

- Eric M. Jones. "Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - Transcripts and audio clips of important parts of the mission - "Apollo 11 image library". NASA. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - Hundreds of high-resolution images of the mission, including assembled panoramas. Captions written by Eric M. Jones - "Apollo Mission Traverse Maps". USGS. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - Several maps showing routes of moonwalks - "Google Moon". - with lunar landing sites tagged

- Neil Armstrong's First Words on the Moon Video

- Neil Armstrong's First Words on the Moon Audio

- Cockpit Voice Recordings of the actual moon landing Audio

- Apollo Lunar Surface VR Panoramas QTVR panoramas

- Apollo Image Archive

- Apollo Video Footage

- Footage of the complete journey from takeoff to splashdown - Video

- Apollo/Saturn V Development Apollo 11 Launch ApolloTV.net Video

- Real-time audiovisual recreation of the Apollo 11 mission to coincide with the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11, from the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum