Caucasian Albania: Difference between revisions

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

In 1953 twelve denarii of Augustus were unearthed.<ref name="IB"/> In 1958 one denarius, coined in ca. 82 AD, was revealed in the [[Şamaxı]] trove.<ref name="IB"/> |

In 1953 twelve denarii of Augustus were unearthed.<ref name="IB"/> In 1958 one denarius, coined in ca. 82 AD, was revealed in the [[Şamaxı]] trove.<ref name="IB"/> |

||

===Parthian |

===Parthian period=== |

||

{{main|Arsacid Dynasty of Caucasian Albania}} |

{{main|Arsacid Dynasty of Caucasian Albania}} |

||

{{see|Parthians|Parthian language}} |

{{see|Parthians|Parthian language}} |

||

Revision as of 23:41, 5 October 2009

Albania (Latin Albānia, Greek Ἀλβανία Albanía [1] also referred to as Caucasian Albania for disambiguation; in Modern Armenian: Աղվանք Aġvank’, Parthian Ardhan, Middle Persian Arran)[2] is the historical name for the region of the eastern Caucasus, roughly corresponding to the territory of present-day Republic of Azerbaijan and southern Dagestan.

Name

Aghuank (Old Armenian: Աղուանք Ałuankʿ, Modern Armenian: Աղվանք Aġvank’) is the Armenian name for Caucasian Albania. Armenian authors mention that the name derived from the word “Aghu” («Աղու») meaning amiable in Armenian. The term Aghuank is polysemous and is also used in Armenian sources to denote the region between the Kur and Araxes rivers as part of Armenia[3]. In the latter case it is sometimes used in the form "Armenian Aghuank" or "Hay-Aghuank" [4][5][6].

The Armenian historian of the region, Movses Kaghankatvatsi, also explains the name Aghvank as a derivation from the word Aghu (Armenian for sweet, soft, tender), which, he said, was the nickname of Caucasian Albania's first governor Arran and referred to his lenient personality. [7] Moses of Kalankatuyk and other ancient sources explain Arran or Arhan as the name of the legendary founder of Caucasian Albania (Aghvan) or even as the Iranic tribe known as Alans (Alani), who in some versions was son of Noah's son Yafet (Japheth)[8]. James Darmesteter, translator of the Avesta, compared Arran with Airyana Vaego[9] which he also considered to have been in the Araxes-Ararat region[10], although modern theories tend to place this in the east of Iran.

The Parthian name for the region was Ardhan ( Middle Persian: Arran).[2] The Arabic was ar-Rān.[11][2]

Geography

In pre-Islamic times, Caucasian Albania/Arran was a wider concept than that of post-Islamic Arran. Ancient Arran covered all eastern Transcaucasia, which included most of the territory of modern day Azerbaijan Republic and part of the territory of Dagestan. However in post-Islamic times the geographic notion of Arran reduced to the territory between the rivers of Kura and Araks.[2]

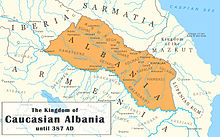

The ancient Caucasian Albania lay on the south-eastern part of the Greater Caucasus mountains. It was bounded by Caucasian Iberia (present-day Georgia) to the west, by Sarmatians of the Caucasus to the north, by the Caspian Sea to the east, and by Armenia to the west along the river Kura [12].

Albania or Arran was a triangle of land, lowland in the east and mountainous in the west, formed by the junction of Kura and Aras rivers,[2] including the highland and lowland Karabakh[2] (Artsakh[13][dubious – discuss]), Mil plain and parts of the Mughan plain, and in the pre-Islamic times, corresponded roughly to the territory of modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan[2].

The districts of Albania[clarification needed] were the following [14]:

- Kambysene

- Getaru

- Elni / Xeni

- Begh

- Shake

- Xolmaz

- Kapalak

- Hambasi

- Gelavu

- Hejeri

- Kaladasht

The kingdom's capital during antquity was Qabala (Kapalak). [15] The name "Albania" is Greek and Latin, and denotes "mountainous land";[1] the native name for the country is unknown.[16]

Classical sources are unanimous in making the Kura River (Cyros) the frontier between Armenia and Albania [14]. The original territory of Albania was approximately 23.000 km² [17]. In the late fourth century, after the partition of Armenia between Byzantium and Persia, the Albanians (with Persian connivance) acquired the Armenian lands in the south of Kura, which comprised the Armenian principalities of Artsakh, Utik, Gardman, Shakashen and Koght [14]. Thus, after 387 the territory of Caucasian Albania, sometimes referred to by scholars as "Greater Albania,"[14] grew to about 45,000 km².[17] In the fifth century the capital was transferred to Partav in Utik, reported to have been built in the mid-fifth century by the King Vache II of Albania,[18] but according to M. L. Chaumont, it existed earlier as an Armenian city.[19]

In a medieval chronicle "Ajayib-ad-Dunia", written in the 13th century by an unknown author, Arran is said to have been 30 farsakhs (200 km) in width, and 40 farsakhs (270 km) in length. All the right bank of the Kura river until it joined with the Aras was attributed to Arran (the left bank of the Kura was known as Shirvan). The boundaries of Arran have shifted throughout history, sometimes encompassing the entire territory of the present day Republic of Azerbaijan, and at other times only parts of the South Caucasus. In some instances Arran was a part of Armenia[20].

Medieval Islamic geographers gave descriptions of Arran in general, and of its towns, which included Barda, Beylagan, and Ganja, along with others.

History

Median and Achaemenid era

According to a quite reasonable hypothesis, Caucasian Albania was incorporated in the Median empire[19]. Persian penetration into this region at a very early date is connected with the need to defend the northern frontier of the Iranian empire.[19][18]. Possibly already under the Achaemenids some measures were taken to protect the Caucasian passes against the invaders however the foundation of Darband and series of gates is traditionally ascribed to the Sassanid empire.[18] Albania was incorporated in the Achaemenid empire and were under the command of the satrapy of Media[19][21] in the later period.

Hellenistic era

The Roman historian Arrian mentions (perhaps anachronistically) the Caucasian Albanians for the first time in the battle of Gaugamela, where the Albanians, Medes, Cadussi and Sacae were under the command of Atropates[19].

An Albanian kingdom was founded in the second century BC. Albanians are mentioned for the first time in 331 BC at the Battle of Gaugamela as participants from the satrapy of Media, although their mention here is "perhaps anachronistic," according to Robert Hewsen.[19]

Albania first appears in history as a vassal state in the empire of Tigranes the Great of Armenia (95-56 BC). [22] The kingdom of Albania emerged in the eastern Caucasus in 2nd or 1st century B.C. and along with the Georgians and Armenians formed one of the three nations of the Southern Caucasus.[14][23] Albania came under strong Armenian religious and cultural influence.[18][24][25][26][27]

Herodotus, Strabo, and other classical authors repeatedly mention the Caspians but do not seem to know much about them; they are grouped with other inhabitants of the southern shore of the Caspian Sea, like the Amardi, Anariacae, Cadusii, Albani (see below), and Vitii (Eratosthenes apud Strabo, 11.8.8), and their land (Caspiane) is said to be part of Albania (Theophanes Mytilenaeus apud Strabo, 11.4.5).[28]

In the 2nd century BC parts of Albania were conquered by the kingdom of Armenia, presumably from Medes [16] (although possibly it was earlier part of Orontid Armenia).[29]

The original population of the territories on the right bank of Kura before the Armenian conquest consisted of various autochthonous people. Ancient chronicles provide the names of several peoples that populated these districts, including the regions of Artsakh and Utik. These were Utians, Mycians, Caspians, Gargarians, Sakasenians, Gelians, Sodians, Lupenians, Balas[ak]anians, Parsians and Parrasians.[16] According to Robert H. Hewsen, these tribes were "certainly not of Armenian origin", and "although certain Iranian peoples must have settled here during the long period of Persian and Median rule, most of the natives were not even Indo-Europeans."[16] He also states that the several peoples of the right bank of Kura "were highly Armenicized and that many were actually Armenians per se cannot be doubted." Many of those people were still being cited as distinct ethnic entities when the right bank of Kura was acquired by the Caucasian Albanians in 387 AD. [16]

Roman Empire

There was an enduring relation of Albania with Ancient Rome. The Latin rock inscription close to Boyukdash mountain in Gobustan, which mentions Legio XII Fulminata and centurion Lucius Julius Maximus, is the world's easternmost Roman evidence known.[30] In Azerbaijan Romans reached the Caspian Sea for the first time.[30]

The Roman coins circulated in Caucasian Albania till the end of the 3rd century AD.[31] Two denarii, unearthed in the 2nd century BC layer, were minted by Clodius and Caesar.[31] The coins of Augustus are ubiquitous.[31] The Qabala treasures revealed the denarii of Otho, Vespasian, Trajan and Hadrian.

In 69-68 BC Lucullus, having beat Armenian ruler Tigranes II, approached the borders of Caucasian Albania and was succeeded by Pompey.[32]

After the 66-65 BC wintering Pompey launched the Iberian campaign. It is reported by Strabo upon the account of Theophanes of Mytilene who participated in it.[33] As testified by Kamilla Trever, Pompey reached the Albanian border at Qazakh Rayon. Igrar Aliyev showed that this region called Cambysene was inhabited mainly by stock-breeders at the time. When fording the Alazan river, he was attacked by forces of Oroezes, King of Albania, and eventually defeated them. According to Plutarch, Albanians "were led by a brother of the king, named Cosis, who as soon as the fighting was at close quarters, rushed upon Pompey himself and smote him with a javelin on the fold of his breastplate; but Pompey ran him through the body and killed him".[34] Plutarch also reported that "after the battle, Pompey set out to march to the Caspian Sea, but was turned back by a multitude of deadly reptiles when he was only three days march distant, and withdrew into Lesser Armenia".[35]. The first kings of Albania were certainly the representatives of the local tribal nobility, to which attest their non-Armenian and non-Iranian names (Oroezes, Cosis and Zober in Greek sources).[36].

According to Dio Cassius Pompey crossed the river Cambysis, which Azerbaijani scholar Seyran Veliyev upon the accounts of Plinius the Elder and Ptolemy identifies with the Pirsaat River.[37] Veliyev concedes that Albanians could palisade against Romans at the narrowest and thus the most convenient point of the Kura River - near Mingachevir. Veliyev assumes further that Pompey, having crossed Kura near Mingachevir, deepened to Abans (most likely the Sumgayit River) at the height of the summer.[38] Pompey could cross the Shirvan Steppe and at Cambysis according to Veliyev the Romans turned to the mountains. They passed through deserted Gobustan and reached one of the sources of Sumgayit River, finding themselves near the forests in native Albanian lands.[38] The Romans won an encounter with Albanians there, but Pompey was forced to bury the hatchet. According to Plutarch, he was in a three-day way far from the sea by that time.[39]

During the reign of Roman emperor Hadrian (117-138) Albania was invaded by the Alans, an Iranian nomadic group.[40]

The population of Caucasian Albania of the Roman period is believed to have belonged to either the Northeast Caucasian peoples[2] or the South Caucasian peoples[41]. According to Strabo, the Albanians were a group of 26 tribes which lived to the north of the Kura river and each of them had its own king and language.[16] Sometime before the 1st century BC they federated into one state and were ruled by one king [42].

Strabo wrote of the Caucasian Albanians in the first century BC:

At the present time, indeed, one king rules all the tribes, but formerly the several tribes were ruled separately by kings of their own according to their several languages. They have twenty-six languages, because they have no easy means of intercourse with one another [42]

In 1899 a silver plate featuring Roman toreutics was excavated near Qalagah.

The rock inscription near the south-eastern part of Boyukdash's foot (70 km from Baku) was discovered on June 2, 1948 by Azerbaijani archaeologist Ishag Jafarzadeh. The legend is IMPDOMITIANO CAESARE·AVG GERMANIC L·IVLIVS MAXIMVS> LEG XII·FVL. According to Domitian's titles in it, the related march took place between 84 and 96. The inscription was studied by Russian expert Yevgeni Pakhomov, who assumed that the associated campaign was launched to control the Derbent Gate and that the XII Fulminata has marched out either from Melitene, its permanent base, or Armenia, where it might have moved from before.[43] Pakhomov supposed that the legion proceeded to the spot continually along the Aras River. The later version, published in 1956, states that the legion was stationing in Cappadocia by that time whereas the centurion might have been in Albania with some diplomatic mission because for the talks with the Eastern rulers the Roman commanders were usually sending centurions.[44]

In 1953 twelve denarii of Augustus were unearthed.[31] In 1958 one denarius, coined in ca. 82 AD, was revealed in the Şamaxı trove.[31]

Parthian period

Under Parthian rule, Iranian political and cultural influence increased in the region.[45] Whatever the sporadic suzerainty of Rome, the country was now a part—together with Iberia (East Georgia) and (Caucasian) Albania, where other Arsacid branched reigned—of a pan-Arsacid family federation[45]. Culturally, the predominance of Hellenism, as under the Artaxiads, was now followed by a predominance of “Iranianism,” and, symptomatically, instead of Greek, as before, Parthian became the language of the educated[45]. An incursion in this era was made by the Alans who between 134 and 136 attacked Albania, Media, and Armenia, penetrating as far as Cappadocia. But Vologases persuaded them to withdraw, probably by paying them.

Sassanid period

In 252-253 AD Caucasian Albania, along with Caucasian Iberia and Greater Armenia, was conquered and annexed by the Sassanid Empire. Albania became a vassal state of the Sassanid Empire,[46] and retained its monarchy, however according to M. L. Chaumont the Albanian king had no real power and most civil, religious, and military authority lay with the Sassanid marzban (military governor) of the territory.[19]

In 297 the treaty of Nisibis stipulated the reestablishment of the Roman protectorate over Iberia, but Albania remained an integral part of the Sasanian Empire. Albania was mentioned among the Sasanian provinces listed in the trilingual inscription of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rustam.[47][48]

In the middle of the fourth century the king of Albania Urnayr arrived in Armenia and was baptized by Gregory the Illuminator, but Christianity spread in Albania only gradually, and the Albanian king remained loyal to the Sassanids. After the partition of Armenia between Byzantium and Persia (in 387 AD), Albania with Sassanid help was able to seize from Armenia all the right bank of the river Kura up to river Araxes, including Artsakh and Utik.[19]

Sasanian king Yazdegerd II passed an edict requiring all the Christians in his empire to convert to Mazdaism, fearing that Christians might ally with Roman Empire, which had recently adopted Christianity. This led to a rebellion of Albanians, along with Armenians and Iberians. In a battle that took place in 451 AD in the Avarayr field, the allied forces of the Armenian, Albanian and Iberian kings, devoted to Christianity, suffered defeat at the hands of the Sassanid army. Many of the Armenian nobility fled to the mountainous regions of Albania, particularly to Artsakh, which became a center for resistance to Sassanid Persia. The religious center of the Albanian state also moved here. However, the Albanian king Vache, a relative of Yazdegerd II, was forced to convert to the official religion of the Sasanian empire, but soon reverted back to Christianity.

In the middle of the fifth century by the order of the Persian king Peroz I Vache built in Utik the city initially called Perozabad, and later Partaw and Barda, and made it the capital of Albania.[49] Partaw was the seat of the Albanian kings and Persian marzban, and in 552 A.D. the seat of the Albanian Catholicos was also transferred to Partaw.[19][50]

After the death of Vache, Albania remained without a king for thirty years. The Sasanian Balash reestablished the Albanian monarchy by making Vachagan, son of Yazdegerd and brother of the previous king Vache, the king of Albania.

By the end of the fifth century, the ancient Arsacid royal house of Albania, a branch of the ruling dynasty of Parthia, became extinct, and in the sixth century it was replaced by princes of the Persian or Parthian Mihranid family, who claimed descent from the Sasanians. They assumed a Persian title of Arranshah (i.e.the shah of Arran, the Persian name of Albania).[2] The ruling dynasty was named after its Persian founder Mihran, who was a distant relative of the Sasanians.[51] The Mihranid dynasty survived under Muslim suzerainty until 821-2.[52]

In the late sixth – early seventh centuries the territory of Albania became an arena of wars between Sasanian Persia, Byzantium and the Khazar kaganate, the latter two very often acting as allies. In 628, during the Third Perso-Turkic War, the Khazars invaded Albania, and their leader Ziebel declared himself lord of Albania, levying a tax on merchants and the fishermen of the Kura and Araxes rivers "in accordance with the land survey of the kingdom of Persia". Most of Transcaucasia was under Khazar rule before the arrival of the Arabs.[18] The Albanian kings retained their rule by paying tribute to the regional powers. According to Peter Golden, "steady pressure from Turkic nomads was typical of the Khazar era, although there are no unambiguous references to permanent settlements",[53] while Vladimir Minorsky stated that, in Islamic times, "the town of Qabala lying between Sharvan and Shakki was a place where Khazars were probably settled".[11]

Christianization

The ancient pagan religion of Albania was centered on the worship of three divinities, designated by Interpretatio Romana as Sol, Zeus, and Luna.

Christianity started to enter Caucasian Albania at an early date - according to Movses Kaghankatvatsi, in the 1st century A.D. the first Christian church in the region was built by St. Eliseus, a disciple of Thaddeus of Edessa, at a place called Gis (believed to be the modern-day Kish).

In 498 AD (in other sources, 488 AD) in the settlement named Aluen (Aghuen) (present day Agdam region of Azerbaijan), an Albanian church council convened to adopt laws further strengthening the position of Christianity in Albania.

Albanian churchmen took part in missionary efforts in the Caucasus and Pontic regions. In 682, the catholicos, Israel, led an unsuccessful delegation to convert Alp Iluetuer, the ruler of the North Caucasian Huns, to Christianity. The Albanian Church maintained a number of monasteries in the Holy Land.[54]

Historians believe that after the Caucasian Albanians were Christianized in the 4th century, the western parts of the population were gradually assimilated by the ancestors of modern Armenians,[55], and the eastern parts of Caucasian Albania were Islamized and absorbed by Iranian[56] and subsequently Turkic peoples(modern Azerbaijanis)[16]. Small remnants of this group continued to exist on their own and be known as Udi people.[57].

It is believed that during the ancient and medieval eras parts of the population of Caucasian Albanian were assimilated and might have played a role in the ethnogenesis of the Azerbaijanis, the Armenians of the Nagorno-Karabakh, the Georgians of Kakhetia, the Laks, the Lezgins and the Tsakhurs of Daghestan.[58]

Islamic era

In the middle of the seventh century, the kingdom was overrun by the Arabs and, like all Islamic conquests at the time, incorporated into the Caliphate. The king Javanshir of Albania, the most prominent ruler of Mihranid dynasty, fought against the Arab invasion of caliph Uthman on the side of the Sasanid Iran. Facing the threat of the Arab invasion on the south and the Khazar offensive on the north, Javanshir had to recognize the Caliph’s suzerainty. The Arabs then reunited the territory with Armenia under one governor.[19]

By the eighth century, Caucasian Albania had been reduced to a strictly geographical and ecclesiastical connotation,[59] and was referred to as such by medieval Armenian historians; it existed as a number principalities, such as that of Khachen, along with various Caucasian, Iranian and Arabic principalities: the principality of Shaddadids, the principality of Shirvan, the principality of Derbent, and so on Most of the region was ruled by the Sajid Dynasty of Azerbaijan from 890 to 929.

Following the Arab invasion of Iran, the Arabs invaded the Caucasus in the 8th century and most of the former territory of Caucasian Albania was included under the name of Arran. This region was at times part of the Abbasid province of Armenia based on numismatic and historical evidence. Dynasties of Parthian or Persian descent, such as the Mihranids had come to rule the territory during Sassanian times. Its kings were given title Arranshah, and after the Arab invasions, fought against the caliphate from the late 7th to middle 8th centuries.

Early Muslim ruling dynasties of the time included Rawadids, Sajids, Salarids, Shaddadids, Shirvanshahs, and the Sheki and Tiflis emirates. The principal cities of Arran in early medieval times were Barda (Partav) and Ganja. Barda reached prominence in the 10th century, and was used to house a mint. Barda was sacked by the Rus and Norse several times in 10th century as result of the Caspian expeditions of the Rus. Barda never revived after these raids and was replaced as capital by Baylaqan, which in turn was sacked by the Mongols in 1221. After this Ganja rose to prominence and became the central city of the region. The capital of the Shaddadid dynasty, Ganja was considered the "mother city of Arran" during their reign.

The territory of Arran became a part of the Seljuk empire, followed by the Ildegizid state. It was taken briefly by the Khwarizmid dynasty and then overran by Mongol Hulagu empire in the 13th century. Later, it became a part of Chobanid, Jalayirid, Timurid, and Safavid states.

Alphabet and language

A Caucasian Albanian alphabet of fifty-two letters, some bearing a resemblance to Armenian or Georgian characters, has only survived through a few manuscripts and inscriptions[61]. It was rediscovered in 1937 by a Georgian scholar, Ilia Abuladze, in an Armenian manuscript from the 15th century. The manuscript, Matenadaran No. 7117, is a language manual, presenting different alphabets for comparison - Armenian, Greek, Latin, Syrian, Georgian, Coptic, and Caucasian Albanian among them. The alphabet was titled: "Aluanic girn e" (Armenian: Աղվանից գիրն Է, meaning, "Albanian letters").

According to Movses Kaghankatvatzi, the Caucasian Albanian alphabet was devised by Mesrob Mashdots, an Armenian monk, theologian and linguist and inventor of the Armenian alphabet.[62] A disciple of Saint Mesrob, Koriun, in The Life of Mashtots, wrote:

Then there came and visited them an elderly man, an Albanian named Benjamin. And he [Mesrop] inquired and examined the barbaric diction of the Albanian language, and then through his usual God-given keenness of mind invented an alphabet, which he, through the grace of Christ, successfully organized and put in order.[63]

The distinctive Caucasian Albanian language persisted into early Islamic times, and Muslim geographers Al-Muqaddasi, Ibn-Hawqal and Al-Istakhri recorded that the language which they called Arranian was still spoken in the capital Barda and the rest of the country in the 10th century.[2]

The Udi language, spoken by 8000 people mostly in Azerbaijan, and also Georgia, is thought to be the last remnant of the language once spoken in Caucasian Albania.[64]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b James Stuart Olson. An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. ISBN 0313274975

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bosworth, Clifford E. Arran. Encyclopedia Iranica. Cite error: The named reference "Bosworth" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ History of Armenia composed by abbot Michael vardapet Chamcheants («Պատմութիւն Հայոց, հորինեալ ի հայր Միքայել վարդապէտե Չամչեանց»), Venice, 1786, p. 131.

- ^ A. Yanovskiy, About the Ancient Caucasian Albania. (А. Яновский, О древней Кавказской Албании. Журнал МНЛ, 1864, ч. II, с. 180.)

- ^ S. V. Yushkov, On question of the boundaries of ancient Albania. Moskow, 1937, p. 137. (С. В. Юшков, К вопросу о границах древней Албании. «Исторические записки АН СССР», т. I, М., 1937, с. 137.)

- ^ Ghevond Alishan, Aghuank (Ղևոնդ Ալիշան, «Աղուանք»), Venice: "Bazmavep", 1970, N 11-12, p. 341.

- ^ The History of Aluank by Moses of Kalankatuyk. Book I, chapter IV

- ^ Moses Kalankatuatsi. History of country of Aluank. Chapter IV.

- ^ Darmesteter's translation and notes

- ^ Darmesteter, James (trans., ed.). "Vendidad." Zend Avesta I (SBE 4). Oxford University Press, 1880. p. 3, p. 5 n.2,3.

- ^ a b V. Minorsky. Caucasica IV. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 15, No. 3. (1953), p. 504

- ^ Anon. Armenian "Geography" («Աշխարհացոյց»), Sec. IV, Asia, The lands of Greater Asia.

- ^ C. J. F. Dowsett. "The Albanian Chronicle of Mxit'ar Goš", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 21, No. 1/3. (1958) p. 475: "In Albania, Xacen, part of the old province of Arcax, had preserved its independence, and we know that it was partly at the request of one of its rulers, Prince Vaxtang, that Mxit'ar composed his lawbook."

- ^ a b c d e Robert H. Hewsen, Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001, pp. 40-41. ISBN 978-0-226-33228-4

- ^ Strabo had no knowledge of any city in Albania, although in the first century AD Pliny mentions the initial capital of the kingdom - Qabala. The name of the city was pronounced in many different ways including Kabalaka, Shabala, Tabala, present-day Qabala

- ^ a b c d e f g Cite error: The named reference

Hewsenwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Template:Hy icon Yeremyan, Suren T. Armenia According to "Asxaracoic". Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1963, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e Minorsky, Vladimir. A History of Sharvan and Darband in the 10th-11th Centuries. Cambridge, 1958.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chaumont, M. L. Albania. Encyclopedia Iranica. Cite error: The named reference "Chaumont" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Abi Ali Ahmad ibn Umar ibn Rustah, al-A'laq Al-Nafisah, Tab'ah 1,Bayrut : Dar al-Kutub al-ʻIlmiyah, 1998, pg 96-98.

- ^ Bruno Jacobs, "ACHAEMENID RULE IN Caucasus" in Encyclopedia Iranica. January 9, 2006. Excerpt: "Achaemenid rule in the Caucasus region was established, at the latest, in the course of the Scythian campaign of Darius I in 513-12 BCE. The Persian domination of the cis-Caucasian area (the northern side of the range) was brief, and archeological findings indicate that the Great Caucasus formed the northern border of the empire during most, if not all, of the Achaemenid period after Darius"

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H (2001). Armenia: A Historcial Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-2263-3228-4.

- ^ Тревер К. В. Очерки по истории и культуре кавказской Албании IV в. до н. э. — VII в. н. э. М.-Л., 1959, p 144

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. Article: Azerbaijan

- ^ Walker, Christopher J. Armenia and Karabagh: The Struggle for Unity. London: Minority Rights Group Publications, 1991, p. 10.

- ^ Istorija Vostoka. V 6 t. T. 2, Vostok v srednije veka Moskva, «Vostochnaya Literatura», 2002. ISBN 5-02-017711-3

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians," in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity, Chicago: 1982

- ^ Schmitt Rüdiger.Caspians. Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H (2001). Armenia: A Historcial Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 32, 58. ISBN 0-2263-3228-4.

- ^ a b Template:Ru iconЕ.В. Федорова. "Императорский Рим в лицах". Ancientcoins.narod.ru. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ a b c d e Template:Ru iconИльяс Бабаев. "Какие монеты употребляли на рынках Азербайджана". Irs-az.com. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Template:Ru icon"Страбон о Кавказской Албании". Irs-az.com. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ К. Алиев. К вопросу об источниках Страбона в описании древней Кавказской Албании. Ж. Доклады АН Азерб. ССР, XVI, 1960, № 4, с. 420-421

- ^ Plutarch, The Parallel Lives. Pompey, 35

- ^ Plutarch, The Parallel Lives: "Pompey", 36

- ^ Тревер К. В. Очерки по истории и культуре кавказской Албании IV в. до н. э. — VII в. н. э. М.-Л., 1959, p 145

- ^ Велиев, Сейран (1987). Древний, древний Азербайджан. Гянджлик. p. 161.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Велиев, p. 162

- ^ Plut. Pomp. 36.1, challenged in Wirth G. Pompeius-Armenien-Farther. Mutmabungen zu einer Bewaltigung einer Krisensituation // Bonner Jahrbucher. 1983.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911, s.v. "Albania, Caucasus".

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon (1994). The Caucasian Knot. Zed Books. p. 54. ISBN 1856492885.

The Caucasian Albania state was established during the second to first centuries BC and, according to Strabo, was made up of 26 tribes. It seems that their language was Ibero-Caucasian.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Strabo. Geography, book 11, chapter 14.

- ^ Пахомов, Е.А. Римская надпись I в. н.э. и легион XII фульмината. "Изв. АН Азерб. ССР", 1949, №1

- ^ Всемирная история. Энциклопедия, том 2, 1956, гл. XIII

- ^ a b c Toumanoff, Cyril. The Arsacids. Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge history of Iran, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 052120092X, 9780521200929, p. 141

- ^ Gignoux. "Aneran". Encyclopaedia Iranica: "The high priest Kirder, thirty years later, gave in his inscriptions a more explicit list of the provinces of Aneran, including Armenia, Georgia, Albania, and Balasagan, together with Syria and Asia Minor."

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica: "The list of provinces given in the inscription of Ka'be-ye Zardusht defines the extent of the empire under Shapur

- ^ Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Book 1, Chapter XV

- ^ Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Book 2, Chapter VI

- ^ Moses Kalankatuatsi. History of country of Aluank. Chapter XVII. About the tribe of Mihran, hailing from the family of Khosrow the Sasanian, who became the ruler of the country of Aluank

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran. 1991. ISBN 0521200938

- ^ An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples by Peter B. Golden. Otto Harrasowitz (1992), ISBN 3-447-03274-X (retrieved 8 June 2006), p. 385–386.

- ^ Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Book 2, Chapter LII

- ^ Ronald G. Suny: What Happened in Soviet Armenia? Middle East Report, No. 153, Islam and the State. (Jul. - Aug., 1988), pp. 37-40.

- ^ История Востока. В 6 т. Т. 2. Восток в средние века.]М., «Восточная литература», 2002. ISBN 5-02-017711-3 (History of the East. In 6 volumes. Volume 2. Moscow, publishing house of the Russian Academy of sciences «East literature»): The multi-ethnic population of Albania left-bank at this time is increasingly moving to the Persian language. Mainly this applies to cities of Aran and Shirwan, as begin from 9-10 centuries named two main areas in the territory of Azerbaijan. With regard to the rural population, it would seem, mostly retained for a long time, their old languages, related to modern Daghestanian family, especially Lezgin. (Russian text: Пестрое в этническом плане население левобережнoй Албании в это время все больше переходит на персидский язык. Главным образом это относится к городам Арана и Ширвана, как стали в IX-Х вв. именоваться два главные области на территории Азербайджана. Что касается сельского населения, то оно, по-видимому, в основном сохраняло еще долгое время свои старые языки, родственные современным дагестанским, прежде всего лезгинскому.

- ^ Udis by Igor Kuznetsov

- ^ Stuart, James (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 27. ISBN 0313274975.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Chorbajian. Caucasian Knot, pp. 63-64.

- ^ Joseph L. Wieczynski, George N. Rhyne. The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History. Academic International Press, 1976. ISBN 0875690645, 9780875690643

- ^ Thomson, Robert W. (1996). Rewriting Caucasian History: The Medieval Armenian Adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198263732.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Moses Kalankatuyk, The History of Aluank, I, 27 and III, 24.

- ^ See Koriun, Ch. 16.

- ^ Caucasian Albanian Script. The Significance of Decipherment by Dr. Zaza Alexidze.

References

- Template:Ru icon Movses Kalankatuatsi. The History of Aluank. Translated from Old Armenian (Grabar) by Sh.V.Smbatian, Yerevan, 1984.

- Template:En icon Koriun, The Life of Mashtots, translated from Old Armenian (Grabar) by Bedros Norehad.

- Template:Ge icon Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of Albania. Translated by L. Davlianidze-Tatishvili, Tbilisi, 1985.

- Template:Ru icon Movses Khorenatsi The History of Armenia. Translated from Old Armenian (Grabar) by Gagik Sargsyan, Yerevan, 1990.

- Template:En icon Ilia Abuladze. About the discovery of the alphabet of the Caucasian Albanians. - "Bulletin of the Institute of Language, History and Material Culture (ENIMK)", Vol. 4, Ch. I, Tbilisi, 1938.