History of the Jews in the United States: Difference between revisions

Tag: references removed |

|||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

===Local developments=== |

===Local developments=== |

||

never mind |

|||

====Clarksburg, West Virginia==== |

|||

jews are no good laywers who are out to steal ur money |

|||

====Wichita, Kansas==== |

====Wichita, Kansas==== |

||

Revision as of 14:13, 8 November 2010

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

The History of American Jews has been part of the national fabric since colonial times. Until the 1830s the Jewish community of Charleston, South Carolina was the most numerous in North America. With the large scale immigration of Jews from Germany in the 19th century, they established themselves in many small towns and cities. A much larger immigration of Eastern European Jews, 1880–1914, brought a large, poor, traditional element to New York City. Refugees arrived from Europe after World War II, and many arrived from the Soviet Union after 1970.

In the 1940s Jews comprised 3.7% of the national population. Today the population is about 5 million—under 2% of the national total—and shrinking because of small family sizes and intermarriage. The largest population centers are the metropolitan areas of New York (2.1 million in 2000), Los Angeles (668,000), Miami (331,000), Philadelphia (285,000), Chicago (265,000) and Boston (254,000).[1]

Jewish emigration

The Jewish population of the US is the product of waves of immigration primarily from Europe; it was initially inspired by the pull of social and entrepreneurial opportunities, and later as a refuge from the push of continuing antisemitism there. Few ever returned to Europe, although committed advocates of Zionism have emigrated to Israel.[2]

America and its culture developed as an easy-to-enter "Melting Pot" for many cultures, creating a new commonality of culture and political values. This open culture allowed many minority groups, including Jews, to flourish in Christian and predominantly Protestant America. Antisemitism in the United States has always been less common than in other historic areas of Jewish population, whether in Christian Europe or in the Muslim Middle East, where most nations developed around different majority ethnicities or languages.

From a population of 1000-2000 Jewish residents in 1790, mostly Dutch Sephardic Jews, Jews from England, and British subjects, the American Jewish community grew to about 15,000 by 1840,[3] and to about 250,000 by 1880. Most of the mid-19th century Jewish immigrants to the US came from German-speaking states, as part of the larger concurrent German migration. They all initially spoke German, and settled across the nation, assimilating with their new countrymen; the Jews among them commonly engaged in trade, manufacturing, and operated dry goods (clothing) stores in many cities.

Between 1880 and the start of World War I in 1914, about two million Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews immigrated from Eastern Europe, where repeated pogroms made life unpredictable. They came from Jewish populations of Russia, the Pale of Settlement (modern Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova), and the Russian-controlled portions of Poland. The latter group clustered in New York City, created the garment industry there, which supplied the dry goods stores across the country, and were heavily engaged in the trade unions. This wave was also part of a larger migration of eastern and southern European immigrants, which was unlike the historically predominant American demographic from northern and western Europe; Records indicate between 1880 and 1920 that these new immigrants rose from less that five percent of all European immigrants to nearly 50%. This feared change caused renewed nativist sentiment, the birth of the Immigration Restriction League, and congressional studies by the Dillingham Commission from 1907 to 1911. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 established immigration restrictions specifically on these groups, and the Immigration Act of 1924 further tightened and codified these limits. With the ensuing Great Depression, and despite worsening conditions for European Jews, with the rise of Nazi Germany, these quotas remained in place with minor alterations until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Jews quickly created support networks consisting of many small synagogues and Ashkenazi Jewish Landsmannschaften (German for "Territorial Associations") for Jews from the same town or village.

Leaders of the time urged assimilation and integration into the wider American culture, and Jews quickly became part of American life. During World War II, 500,000 American Jews, about half of all Jewish males between 18 and 50, enlisted for service, and after the war, Jewish families joined the new trend of suburbanization, as they became wealthier and more mobile. The Jewish community expanded to other major cities, particularly around Los Angeles and Miami. Their young people attended secular high schools and colleges and met Christians, so that intermarriage rates soared to nearly 50%. Synagogue membership however, grew considerably, from 20% of the Jewish population in 1930 to 60% in 1960.

The earlier waves of immigration and immigration restriction were followed by the Holocaust that destroyed most of the European Jewish community by 1945; these also made the United States the home for the largest Jewish population in the world. In 1900 there were 1.5 million Americans Jews; in 2005 there were 4.9 million. See Historical Jewish population comparisons

On a theological level, American Jews are divided into a number of Jewish denominations, of which the most numerous are Orthodox Judaism, Conservative Judaism and Reform Judaism. Conservative Judaism arose in America and Reform Judaism was popularized by American Jews.

Colonial era

The first Jew to set foot on American soil was Solomon Franco, a merchant who arrived in Boston in 1649; subsequently he was given a stipend from the Puritans there, on condition he leave on the next passage back to Holland.[4] In September of 1654, shortly before the Jewish New Year, twenty-three Jews of Dutch ancestry from Recife, Brazil, arrived in New Amsterdam (New York City). Governor Peter Stuyvesant, tried to enhance his Dutch Reformed Church by discriminating against other religions, but religious pluralism was already a tradition in the Netherlands and his superiors at the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam overruled him.

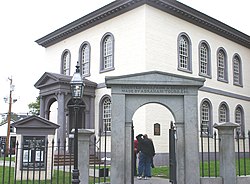

Religious tolerance was also established elsewhere in the colonies; the colony of South Carolina, for example, was originally governed under an elaborate charter drawn up in 1669 by the English philosopher John Locke. This charter granted liberty of conscience to all settlers, expressly mentioning "Jews, heathens, and dissenters."[5] As a result, Charleston, South Carolina has a particularly long history of Sephardic settlement,[6] which in 1816 numbered over 600, then the largest Jewish population of any city in the United States.[7] Sephardic Dutch Jews were also among the early settlers of Newport (where the country's oldest surviving synagogue building stands), Savannah, Philadelphia and Baltimore.[8] In New York City, Shearith Israel Congregation is the oldest continuous congregation started in 1687 having their first synagogue erected in 1728, and its current building still houses some of the original pieces of that first.[9] By the time of American Revolution, the Jewish population in America was very small, with only 1,000-2000, in a colonial population of about 2.5 million.

Revolutionary era

By 1776 and the War of Independence, around 2,000 Jews lived in America, most of them Sephardic Jews of Spanish and Portuguese origin. They played a significant role in the struggle for independence, including fighting the British, with Francis Salvador being the first Jew to die,[10] and playing a key role in financing the revolution, with the most important of the financiers being Haym Solomon.[11] Others, like David Salisbury Franksan, despite loyal service in both the Continental Army and the American diplomatic corps, suffered from his association as aide-de-camp for the traitorous general Benedict Arnold.

President George Washington remembered the Jewish contribution when he wrote to the Sephardic congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, in a letter dated August 17, 1790: "May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in the land continue to merit and enjoy the goodwill of the other inhabitants. While everyone shall sit safely under his own vine and fig-tree and there shall be none to make him afraid."

In 1790, the approximate 2,500 Jews in America faced a number of legal restrictions in various states that prevented non-Christians from holding public office and voting, but Delaware, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Georgia soon eliminated these barriers, as did the Bill of Rights in 1791 generally. Sephardic Jews became active in community affairs in the 1790s, after achieving "political equality in the five states in which they were most numerous."[12] Other barriers did not officially fall for decades in the states of Rhode Island (1842), North Carolina (1868), and New Hampshire (1877). Despite these restrictions, which were often enforced unevenly, there were really too few Jews in 17th- and 18th-century America for anti-Jewish incidents to become a significant social or political phenomenon at the time. The evolution for Jews from toleration to full civil and political equality that followed the American Revolution helped ensure that Antisemitism would never become as common as in Europe.[13]

19th century

Following traditional religious and cultural teachings about improving the lot of their brethren, Jewish residents in the United States began to organize their communities in the early 19th century. Early examples include a Jewish orphanage set up in Charleston, South Carolina in 1801, and the first Jewish school, Polonies Talmud Torah, established in New York in 1806. In 1843, the first national secular Jewish organization in the United States, the B'nai B'rith was established. See also History of Jewish education in the United States (pre-20th century).

Jewish Texans have been a part of Texas History since the first European explorers arrived in the 16th century.[14] Spanish Texas did not welcome easily identifiable Jews, but they came in any case. Jao de la Porta was with Jean Laffite at Galveston, Texas in 1816, and Maurice Henry was in Velasco in the late 1820s. Jews fought in the armies of the Texas Revolution of 1836, some with Fannin at Goliad, others at San Jacinto. Dr. Albert Levy became a surgeon to revolutionary Texan forces in 1835, participated in the capture of Béxar, and joined the Texas Navy the next year.[14]

By 1840, Jews constituted a tiny, but nonetheless stable, middle-class minority of about 15,000 out of the 17 million Americans counted by the U.S. Census. Jews intermarried rather freely with non-Jews, continuing a trend that had begun at least a century earlier. However, as immigration increased the Jewish population to 50,000 by 1848, negative stereotypes of Jews in newspapers, literature, drama, art, and popular culture grew more commonplace and physical attacks became more frequent.

During the 19th century, (especially the 1840s and 1850s), Jewish immigration was primarily of Ashkenazi Jews from Germany, bringing a liberal, educated population that had experience with the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment. It was in the United States during the 19th century that two of the major branches of Judaism were established by these German immigrants: Reform Judaism (out of German Reform Judaism) and Conservative Judaism, in reaction to the perceived liberalness of Reform Judaism.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, approximately 3,000 Jews (out of around 150,000 Jews in the United States) fought on the Confederate side and 7,000 fought on the Union side.[15] Jews also played leadership roles on both sides, with nine Jewish generals and 21 Jewish colonels participating in the War. Judah P. Benjamin, a non-observant Jew, served as Secretary of State and acting Secretary of War of the Confederacy.

By the time of the Civil War, tensions over race and immigration, as well as economic competition between Jews and non-Jews, combined to produce the worst outbreak of antisemitism to that date. Americans on both sides of the slavery issue denounced Jews as disloyal war profiteers, and accused them of driving Christians out of business and of aiding and abetting the enemy.

Major General Ulysses S. Grant was influenced by these sentiments and issued General Order No. 11 expelling Jews from areas under his control in western Tennessee:

The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled …within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.

This order was quickly rescinded by President Abraham Lincoln but not until it had been enforced in a number of towns.[16]

Grant later issued an order "that no Jews are to be permitted to travel on the road southward." His aide, Colonel John V. DuBois, ordered "all cotton speculators, Jews, and all vagabonds with no honest means of support", to leave the district. "The Israelites especially should be kept out…they are such an intolerable nuisance."

The Jews and the government

The first Jewish member of the United States House of Representatives, Lewis Charles Levin, and Senator, David Levy Yulee, were elected in 1845 (although Yulee converted to Episcopalianism the following year). Official government antisemitism continued, however, with New Hampshire only offering equality to Jews in 1871, the last state to do so. Jews also began to organize as a political group in the United States, especially in response to the United States' reaction to the 1840 Damascus Blood Libel.

- For more information, see Relationship of American Jews to the U.S. Federal Government (pre-20th century).

1880-1925

Immigration of Eastern European Jews

None of the early migratory movements assumed the significance and volume of that from Russia and neighboring countries. This emigration, mainly from Russian Poland and other areas of the Russian Empire, began as far back as 1821, but did not become especially noteworthy until after the German immigration fell off in 1870. Though nearly 50,000 Russian, Polish, Galician, and Romanian Jews went to the United States during the succeeding decade, it was not until the pogroms, anti-Jewish uprisings in Russia, of the early 1880s, that the immigration assumed extraordinary proportions. From Russia alone the emigration rose from an annual average of 4,100 in the decade 1871-80 to an annual average of 20,700 in the decade 1881-90. Additional measures of persecution in Russia in the early nineties and continuing to the present time have resulted in large increases in the emigration, England and the United States being the principal lands of refuge. The Romanian persecutions, beginning in 1900, forced large numbers of Jews to seek refuge in the US. Though most of these immigrants arrived on the Eastern seabord, many came as part of the Galveston Movement, through which Jewish immigrants settled in Texas as well as the western states and territories.[17]

By 1924, two million Jews had arrived from Eastern Europe. Growing anti-immigration feelings in the United States at this time, resulted in the National Origins Quota of 1924, which severely restricted immigration from Eastern Europe after that time. The Jewish community took the lead in opposing immigration restrictions, which remained in effect until 1965.

Local developments

never mind

Wichita, Kansas

The Jews of Wichita, Kansas, fashioned an ethnoreligious world that was distinct, vibrant, and tailored to their circumstances. They had migrated west with capital, credit, and know-how, and their family-based businesses were extensions of family businesses in the east. They distinguished themselves in educational, leadership, and civic positions. Predominantly German Jews through the 1880s, their remoteness and small numbers encouraged the practice of Reform Judaism, which in turn increased their interaction with non-Jews and hastened the erosion of their heritage. The arrival of conservative Jews from Eastern Europe after the 1880s brought tension into the Wichita Jewish community, but also stirred an ethnoreligious revival. The German Jews were well-respected in the Wichita community, which facilitated the integration of the Eastern European newcomers. The Jewish community was characterized by a "dynamic tension" between tradition and modernization.[18]

Oakland, California

The Jewish community in Oakland, California, is representative of many cities. Jews played a prominent role, and were among the pioneers of Oakland in the 1850s. In the early years, the Oakland Hebrew Benevolent Society, founded in 1862, was the religious, social, and charitable center of the community. Later, the first synagogue, founded in 1875, took over the religious and burial functions. Jews from Poland predominated in the community, and most of them worked in some aspect of the clothing industry. David Solis-Cohen, the noted author, was a leader in the Oakland Jewish community in the 1870s. In 1879 Oakland's growing Jewish community organized a second congregation, a strictly orthodox group, Poel Zedek. Women's religious organizations flourished, their charitable services extending to needy gentiles as well as Jews. Oakland Jewry was part of the greater San Francisco community, yet maintained its own character. In 1881 the First Hebrew Congregation of Oakland, elected Myer Solomon Levy as its rabbi. The London-born Levy practiced traditional Judaism. Oakland's Jews were pushed hard to excel in school, both secular and religious. Fannie Bernstein was the first Jew to graduate from the University of California at Berkeley, in 1883. First Hebrew Congregation sponsored a Sabbath school which had 75 children in 1887. Oakland Jewry was active in public affairs and charitable projects in the 1880s. Rabbi Myer S. Levy was chaplain to the state legislature in 1885. The Daughters of Israel Relief Society continued its good works both inside and outside the Jewish community. Beth Jacob, the traditional congregation of Old World Polish Jews, continued its separate religious practices while it maintained friendly relations with the members of the first Hebrew Congregation. Able social and political leadership came from David Samuel Hirshberg. Until 1886 he was an officer in the Grand Lodge of B'nai B'rith. He served as Under Sheriff of Alameda County in 1883 and was active in Democratic party affairs. In 1885 he was appointed Chief Clerk of the US Mint in San Francisco. As a politician, he had detractors who accused him of using his position in B'nai B'rith to foster his political career. When refugees from the fire-stricken, poorer Jewish quarter of San Francisco came to Oakland, the synagogue provided immediate aid. Food and clothing were given to the needy and 350 people were given a place to sleep. For about a week the synagogue fed up to 500 people three times a day. A large part of the expenses were paid by the Jewish Ladies' organization of the synagogue.[19]

Progressive movement

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

With the influx of Jews from Central and Eastern Europe many members of the Jewish community were attracted to labor and socialist movements and numerous Jewish newspapers such as Forwerts and Morgen Freiheit had a socialist orientation. Left wing organizations such as the Arbeter Ring and the Jewish People's Fraternal Order played an important part in Jewish community life until World War II.

Jewish Americans were not just involved in nearly every important social movement but in the forefront of promoting such issues as workers rights, civil rights, woman's rights, freedom of religion, peace movements, and various other progressive causes.

Americanization

Jacob Schiff played a major role as a leader of the American Jewish community in the late 19th century. As a wealthy German Jew, Schiff made important decisions regarding the arrival of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. At a time of increasing demand for immigration restriction, Schiff supported and worked for Jewish Americanization. A Reform Jew, he backed the creation of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary of America. He took a stand favoring a modified form of Zionism, reversing his earlier opposition. Above all, Schiff believed that American Jewry could live in both the Jewish and American worlds, creating a balance that made possible an enduring American Jewish community.[20]

The National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW), founded in Chicago in 1893, had the goals of philanthropy and the Americanization of Jewish immigrants. Responding to the plight of Jewish women and girls from Eastern Europe, the NCJW created its Department of Immigrant Aid to assist and protect female immigrants from the time of their arrival at Ellis Island until their settlement at their final destination. The NCJW's Americanization program included assisting immigrants with housing, health, and employment problems, leading them to organizations where women could begin to socialize, and conducting English classes while helping them maintain a strong Jewish identity. The council, pluralistic rather than conformist, continued its Americanization efforts and fought against restrictive immigration laws after World War I. At the forefront of its activities was the religious education of Jewish girls, who were ignored by the Orthodox community.[21]

Philanthropy

Since the 1820s organized philanthropy has been a core value of the Jewish community. In most cities the philanthropic organizations are the center of the Jewish community and activism is highly valued. Much of the money now goes to Israel, as well as hospitals and higher education; previously it went to poor Jews. This meant in the 1880-1930 era wealth German Reform Jews were subsidizing poor Orthodox newcomers, and helping their process of Americanization, thus helping bridge the cultural gap. This convergence brought Jews into the political debates in the 1900-1930 period over immigration restriction. Jews were the leading opponents of restrictions, but could not stop their passage in 1924 or their use to keep out most refugees from Hitler in the 1930s.[22]

Julius Rosenwald (1862–1932) moved to Chicago in the late 1880s. Purchasing a half-interest in 1895, he transformed a small mail order house Sears, Roebuck into the largest retailer in America. He used his wealth for philanthropy targeted especially at the plight of rural blacks in collaboration with Booker T. Washington. From 1917-32 the Julius Rosenwald Foundation set up 5,357 public schools for blacks. He funded numerous hospitals for blacks in the South as well as 24 YMCA's; he was a major contributor to the NAACP and the National Urban League. His major contributions to the University of Chicago and to various Jewish philanthropies were on a similar grand scale. He spent $11 million to fund the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry.[23]

World War I

As early as 1914, the American Jewish community mobilized its resources to assist the victims of the European war. Cooperating to a degree not previously seen, the various factions of the American Jewish community—native-born and immigrant, Reform, Orthodox, secular, and socialist—coalesced to form what eventually became known as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. All told, American Jews raised 63 million dollars in relief funds during the war years and became more immersed in European Jewish affairs than ever before.

Refugees from Nazi Germany

In the years before and during World War II the United States Congress, the Roosevelt Administration, and public opinion expressed concern about the fate of Jews in Europe but consistently refused to permit large-scale immigration of Jewish refugees.

In a report issued by the State Department, Undersecretary of State Stuart Eizenstat noted that the United States accepted only 21,000 refugees from Europe and did not significantly raise or even fill its restrictive quotas, accepting far fewer Jews per capita than many of the neutral European countries and fewer in absolute terms than Switzerland.

According to David Wyman, "The United States and its Allies were willing to attempt almost nothing to save the Jews."[24] +

U.S. opposition to immigration in general in the late 1930s was motivated by the grave economic pressures, the high unemployment rate, and social frustration and disillusionment. The U.S. refusal to support specifically Jewish immigration, however, stemmed from something else, namely antisemitism, which had increased in the late 1930s and continued to rise in the 1940s. It was an important ingredient in America's negative response to Jewish refugees.[25]

About 100,000 German Jews did arrive in the 1930s, escaping Hitler’s persecution.

SS St. Louis

The SS St. Louis sailed from Germany in May 1939 carrying 936 (mainly German) Jewish refugees. On 4 June 1939, it was also refused permission to unload on orders of President Roosevelt as the ship waited in the Caribbean Sea between Florida and Cuba. Initially, Roosevelt showed limited willingness to take in some of those on board. But the Immigration Act of 1924 made that illegal and public opinion was strongly opposed. The ship returned to Europe and 709 passengers survived the Holocaust.

World War II and the Holocaust

The United States’ tight immigration policies were not lifted during the Holocaust, news of which began to reach the United States in 1941 and 1942 and it has been estimated that 190 000 - 200 000 Jews could have been saved during the Second World War had it not been for bureaucratic obstacles to immigration deliberately created by Breckinridge Long and others.[26]

Rescue of the European Jewish population was not a priority for the US during the war, and the American Jewish community did not realize the severity of the Holocaust until late in the conflict.

The Holocaust

During the World War II period the American Jewish community was bitterly and deeply divided, and was unable to form a common front. Most Eastern Europeans favored Zionism, which saw a homeland as the only solution; this had the effect of diverting attention from the horrors in Nazi Germany. German Jews were alarmed at the Nazis but were disdainful of Zionism. Proponents of a Jewish state and Jewish army agitated, but many leaders were so fearful of an antisemitic backlash inside the U.S. that they demanded that all Jews keep a low public profile. One important development was the sudden conversion of most (but not all) Jewish leaders to Zionism late in the war.[27]

The Holocaust was largely ignored by America media as it was happening.[28] Why that was is illuminated by the anti-Zionist position taken by Arthur Hays Sulzberger, publisher of the New York Times, during World War II.[29] Committed to classical Reform Judaism, which defined Judaism as a religious faith and not as a people, Sulzberger insisted that as an American he saw European Jews as part of a refugee problem, not separate from it. As publisher of the nation's most influential newspaper New York Times, he permitted only a handful of editorials during the war on the extermination of the Jews. He supported the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism. Even after it became known that the Nazis had singled out the Jews for destruction, Sulzberger held that all refugees had suffered. He opposed the creation of Israel. In effect, he muted the enormous potential influence of the Times by keeping issues of concern regarding Jews off the editorial page and burying stories about Nazi atrocities against Jews in short items deep inside the paper. In time he grew increasingly out of step with the American Jewish community by his persistent refusal to recognize Jews as a people and despite obvious flaws in his view of American democracy.[30]

While the New York Times was one of the few prestige newspapers owned by Jews, they had a major presence in Hollywood and in network radio. Hollywood films and radio with few exceptions avoided questioning Nazi persecution of Europe's Jews prior to Pearl Harbor. Jewish studio executives did not want to be accused of advocating Jewish propaganda by making films with overtly antifascist themes. Indeed, they were pressured by such organizations as the Anti-Defamation League and by national Jewish leaders to avoid such themes lest American Jews suffer an antisemitic backlash.[31]

Rescue

Despite strong public and political sentiment to the contrary, however, there were some who encouraged the U.S. government to help victims of Nazi genocide. In 1943, just before Yom Kippur, 400 rabbis marched in Washington to draw attention to the plight of Holocaust victims. (See "The Day the Rabbis Marched".) A week later, Senator William Warren Barbour (R; New Jersey), one of a handful of politicians who met with the rabbis on the steps of the U.S.Capitol, proposed legislation that would have allowed as many as 100,000 victims of the Holocaust to emigrate temporarily to the United States. Barbour died six weeks after introducing the bill, and it was not passed. A parallel bill was introduced in the House of Representatives by Rep. Samuel Dickstein (D; New York). This also failed to pass.[32]

During the Holocaust, fewer than 30,000 Jews a year reached the United States, and some were turned away due to immigration policies. The US did not change its immigration policies until 1948.

Impact

The Holocaust had a profound impact on the community in the United States, especially after 1960, as Jews tried to comprehend what had happened, and especially to commemorate and grapple with it when looking to the future.[33] Abraham Joshua Heschel summarized this dilemma when he attempted to understand Auschwitz: "To try to answer is to commit a supreme blasphemy. Israel enables us to bear the agony of Auschwitz without radical despair, to sense a ray [of] God's radiance in the jungles of history."[34]

Postwar

500,000 American Jews (or half of the eligible men) fought in World War II, and after the war younger families joined the new trend of suburbanization. There, Jews became increasingly assimilated and demonstrated rising intermarriage. The suburbs facilitated the formation of new centers, as Jewish school enrollment more than doubled between the end of World War II and the mid-1950s, while synagogue affiliation jumped from 20% in 1930 to 60% in 1960; the fastest growth came in Reform and, especially, Conservative congregations.[35]

Having never been subjected to the Holocaust, the United States stood after the Second World War as the largest, richest, and healthiest center of Judaism in the world. Smaller Jewish communities turned increasingly to American Jewry for guidance and support.[36]

Immediately after the Second World War, some Jewish refugees resettled in the United States, and another wave of Jewish refugees from Arab nations settled in the US after expulsion from their home countries.

Liberal politics

While earlier Jewish elements from Germany were business oriented and voted as conservative Republicans, the wave of Eastern European Jews starting in the 1880s, were more liberal or left wing and became the political majority.[37] Many came to America with experience in the socialist and anarchist movements as well as the Labor Bund, based in Eastern Europe. Many Jews rose to leadership positions in the early 20th century American labor movement and helped to found unions in the "needle trades" (clothing industry) that played a major role in the CIO and in Democratic Party politics. Sidney Hillman of the CIO was especially powerful in the early 1940s at the national level.[37][38]

By the 1930s Jews were a major political factor in New York City, with strong support for the most liberal programs of the New Deal. Since most East European Jews were excluded from the Irish-controlled Democratic Party in New York City they worked through third parties, the American Labor Party and the Liberal Party of New York.[39] By the 1940s they were inside the Democratic Party, and helped overthrow Tammany Hall. They continued as a major element of the New Deal coalition, giving special support to the Civil Rights Movement. By the mid 1960s, however, the Black Power movement caused a growing separation between blacks and Jews, though both groups remained solidly in the Democratic camp.[40][41]

Although German Jews generally leaned Republican in the second half of the 19th century, the East European elements voted Democratic or for left parties since at least 1916, when they voted 55% for Woodrow Wilson.[42] American Jews voted 90% against the Republicans and supported Democrats Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman in the elections of 1940, 1944 and 1948,[42] despite both party platforms supporting the creation of a Jewish state in the latter two elections.[43] During the 1952 and 1956 elections, they voted 60% or more for Democrat Adlai Stevenson, while General Eisenhower garnered 40% for his reelection; the best showing to date for the Republicans since Harding's 43% in 1920.[42] In 1960, 83% voted for Democrat John F. Kennedy, a Catholic, against Richard Nixon, and in 1964, 90% of American Jews voted for Lyndon Johnson; his Republican opponent, arch-conservative Barry Goldwater, was Protestant but his paternal grandparents were Jewish.[44] Hubert Humphrey garnered 81% of the Jewish vote in the 1968 elections, in his losing bid for president against Richard Nixon, a high level of Jewish support not seen since.[42][45]

During the Nixon re-election campaign of 1972, Jewish voters were apprehensive about George McGovern and only favored the Democrat by 65%, while Nixon more than doubled Republican Jewish support to 35%. In the election of 1976, Jewish voters supported Democrat Jimmy Carter by 71% over incumbent president Gerald Ford’s 27%, but in 1980 they abandoned Carter, leaving him with only 45% support, while Republican winner, Ronald Reagan, garnered 39%, and 14% went to independent John Anderson.[42]

During the Reagan re-election campaign of 1984, the Jews returned home to the Democratic Party, giving Reagan only 31% compared to 67% for Democrat Walter Mondale. The same 2-1 pattern reappeared in 1988 as Democrat Michael Dukakis had 64%, while victorious George Bush polled 35%. Bush's Jewish support collapsed during his re-election in 1992, to just 11%, with 80% voting for Bill Clinton and 9% going to independent Ross Perot. Clinton’s re-election campaign in 1996 maintained high Jewish support at 78%, with 16% supporting Bob Dole and 3% for Perot.[42]

Exceptionalism

Historians believe American Jewish history has been characterized by an unparalleled degree of freedom, acceptance, and prosperity that has made it possible for Jews to bring together their ethnic identities with the demands of national citizenship far more effortlessly than Jews in Europe.[46] American Jewish exceptionalism differentiates Jews from other American ethnic groups by means of educational and economic attainments and, indeed, by virtue of Jewish values, including a devotion to political liberalism. As Dollinger (2002) has found, for the last century the most secular Jews have tended toward the most liberal or even leftist political views, while more religious Jews are politically more conservative. Modern Orthodox Jews have been less active in political movements that Reform Jews. They vote Republican more often than less traditional Jews. In contemporary political debate, strong Orthodox support for various school voucher initiatives undermines the exceptionalist belief that the Jewish community seeks a high and impenetrable barrier between church and state.[47]

Creation of the State of Israel

With its establishment in 1948, the State of Israel became the focal point of American Jewish life and philanthropy, as well as the symbol around which American Jews united.[36]

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War of June 1967 marked a turning point in the lives of many 1960s-era Jews. The paralyzing fear of a "second Holocaust" followed by tiny Israel's seemingly miraculous victory over the combined Arab armies arrayed to destroy it struck deep emotional chords among American Jews. Their financial support for Israel rose sharply in the war's wake, and more of them than ever before chose in those years to make Israel their permanent home.[36]

A lively internal debate commenced, following the Six-Day War. The American Jewish community was divided over whether or not they agreed with the Israeli response; the great majority came to accept the war as necessary. A tension existed especially for leftist Jews, between their liberal ideology and (rightist) Zionist backing in the midst of this conflict. This deliberation about the Six-Day War showed the depth and complexity of Jewish responses to the varied events of the 1960s.[48]

Civil rights

Jews were highly visible as leaders of movements for civil rights for all Americans, including themselves and African Americans. Seymour Siegel argues the historic struggle against prejudice faced by Jewish people led to a natural sympathy for any people confronting discrimination. This further led Jews to discuss the relationship they had with African Americans. Jewish leaders spoke at the two iconic marches of the era. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, appeared at the March on Washington on 28 August 1963, noting that "As Jews we bring to this great demonstration, in which thousands of us proudly participate, a twofold experience--one of the spirit and one of our history"[49] Two years later Abraham Joshua Heschel of the Jewish Theological Seminary marched in the front row of the Selma-to-Montgomery march.

Within Judaism, increasing involvement in the civil rights movement caused some tension. Rabbi Bernard Wienberger exemplified this point of view, warning that "northern liberal Jews" put at risk southern Jews who faced hostility from white southerners because of their northern counterparts. However, most known Jewish responses to the civil rights movement and black relations lean toward acceptance and against prejudice, as the disproportionate involvement of Jews in the movement would indicate.[48] Despite this history of participation, relations between African Americans and Jews have sometimes been strained by their close proximity and class differences, especially in New York and other urban areas.

Jewish feminism

In its modern form, the Jewish feminist movement can be traced to the early 1970s in the United States. According to Judith Plaskow, who has focused on feminism in Reform Judaism, the main issues for early Jewish feminists in these movements were the exclusion from the all-male prayer group or minyan, the exemption from positive time-bound mitzvot, and women's inability to function as witnesses and to initiate divorce.[50]

Immigration from the Soviet Union

The last large wave of immigration came from the Soviet Union after 1988, in response to heavy political pressure from the U.S. government. After the 1967 Six-Day War and the liberalization tide in Eastern Europe in 1968, Soviet policy became more restrictive. Jews were denied educational and vocational opportunities. These restrictive policies led to the emergence of a new political group - the 'refuseniks' - whose main goal was emigrating. The refuseniks (Jews who were refused exit visas) attracted the attention of the West, particularly the United States, and became an important factor influencing economic and trade relations between the United States and the Soviet Union. The 1975 Jackson Amendment to the Trade Reform Act linked granting the USSR 'most favored nation' status to liberalization of Soviet emigration laws.[51]

Beginning in 1967 the Soviet Union allowed some Jewish citizens to leave for family reunification in Israel. Due to the break in diplomatic relations between Israel and the USSR, most émigrés traveled to Vienna, Austria, or Budapest, Hungary, from where they were then flown to Israel. After 1976 the majority of émigrés who left on visas for Israel 'dropped out' in Vienna and chose to resettle in the West. Several American Jewish organizations helped them obtain visas and aided their resettlement in the United States and other countries. However Israel wanted them and tried to prevent Soviet Jewish émigrés from resettling in the United States after having committed to immigrating to Israel. Israeli officials pressured American Jewish organizations to desist from aiding Russian Jews who wanted to resettle in the United States. Initially, American Jews resisted Israeli efforts. Following Mikhail Gorbachev's decision in the late 1980s to allow free emigration for Soviet Jews, the American Jewish community agreed to a quota on Soviet Jewish refugees in the U.S., which resulted in most Soviet Jewish émigrés settling in Israel.[52]

About 2 million Soviet Jews emigrated to Israel, the U.S. and Europe combined. Some 100,000 Ashkenazi and Bukharian Jews came to America.[53]

Local Developments

Nashville Tennessee

Reform Jews, predominantly German, became Nashville's largest and most influential Jewish community in the first half of the 20th century; they enjoyed good relations with the Orthodox and Conservative congregations. Some German Jewish refugees resettled in Nashville from 1935 to 1939, helped by prominent Nashville families. Both the Orthodox and Conservative congregations had relocated their synagogues to the suburbs by 1949, and the entire Jewish community had shifted southwest by about five miles. Although subtle social discrimination existed, Nashville's Jews enjoyed the respect of the larger community. Public acceptance, however, required complicity in racial segregation. The Observer, Nashville's weekly Jewish newspaper, tried to find a middle ground between assimilation and particularism, but after years of calling for group solidarity, accepted that the Jewish community was pluralistic.[54]

Palm Springs, California

About 32,000 Jews reside in the Palm Springs area, reports the United Jewish Congress of the Desert. The world-famous desert resort community has been widely known for its Hollywood celebrities. Philadelphia publisher Walter Annenberg opened the Tamarisk Country Club in 1946, after being refused membership in the Los Angeles Lakeside country club. But his connections with Hollywood and corporations alike made his country club a success, and made it a policy to allow Jews and all people, regardless of race and religion, to have access to his facility. Many elderly American Jews from the East coast and the Los Angeles metropolitan area, come to retire in the warm climates such as the Coachella Valley, favoring in golf course and mobile home communities. By the 1990s they were a large component of demography in the desert resort. There are 12 Jewish places of worship, including a Jewish community center in Palm Desert. Palm Springs has the annual "Winter Festival of Lights" parade, which began as a separate parade to celebrate Chanukah in the 1960s. Over time, that and the Christmas-themed parade merged into the one celebrating the season's lights of menorahs, Christmas trees and the calendar new year.[55][56]

Miami

After 1945 many northeastern Jews moved to Florida, especially to Miami, Miami Beach, and nearby cities. They found familiar foods and better weather, and founded more open, less tradition-bound communities, where greater materialism and more leisure-oriented, less disciplined Judaism developed. Many relaxed their religiosity and attended services only during Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. In South Florida synagogue affiliation, Jewish community center membership, and per capita contributions to the United Jewish Appeal and the Jewish Federation are among the lowest of any Jewish community in the United States.[57]

Princeton

The development of Jewish (particularly Orthodox) student life at Princeton University improved rapidly since the end of World War II, when Jewish students were few and isolated. In 1958 Jewish students were more numerous; they protested against the Bicker system of eating club member selection. In 1961 Yavneh House was established as Princeton's first kosher kitchen. In 1971 Stevenson Hall opened as a university-managed kosher eating facility in the midst of the older private eating clubs. Jewish student initiative and Princeton administration openness deserve credit for this progress.[58]

Current situation

American Jews continued to prosper throughout the early 21st century. American Jews are disproportionately represented in business, academia and politics. Forty-five percent of the top 40 of the Forbes 400 richest Americans are Jewish. Twenty percent of professors at leading universities are Jewish. Forty percent of partners in the leading law firms in New York and Washington are Jewish. Thirty percent of American Nobel prize winners in science and 37 percent of all American Nobel winners are Jewish. An estimated thirty percent of Ivy League students are Jewish.[59]

Demographically, the population is not increasing. With their success, American Jews have become increasingly assimilated into American culture, with high intermarriage rates resulting in either a falling or steady population rate at a time when the country was booming. It has not grown appreciably since 1960, comprises a smaller percentage of America's total population than it had in 1920, and seems likely to witness an actual decline in numbers in the decades ahead.[36]

Jews also began to move to the suburbs, with major population shifts from New York and the Northeast to Florida and California. New Jewish organizations were founded to accommodate an increasing range of Jewish worship and community activities, as well as geographic dispersal.

Politically, the Jewish population remained strongly liberal. The heavily Democratic pattern continued into the 21st century. Since 1936 the great majority of Jews have been Democrats. In 2004 74% of Jews voted for Democrat John Kerry, a Catholic of partial Jewish descent, and in 2006 87% voted for Democratic candidates for the House.[60] By the 1990s Jews were becoming prominent in Congress and state governments throughout the country. Jews proved to be strong supporters of the American Civil Rights Movement.

Self identity

Social historians analyze the American population in terms of class, race, ethnicity, religion, gender, region and urbanism. Jewish scholars generally emphasize ethnicity.[61] First, it reflects the suppression of the term "Jewish race," a contested but fairly common usage right into the 1930s and its replacement by the more acceptable "ethnic" usage. Second, it reflects a post-religious evaluation of American Jewish identity, in which "Jewishness" (rather than "Judaism") is taken to be more inclusive, embracing the secularized as well as the religious experiences of Jews.[62]

Korelitz (1996) shows how American Jews during the late 19th and early 20th centuries abandoned a racial definition of Jewishness in favor of one that embraced ethnicity. The key to understanding this transition from a racial self-definition to a cultural or ethnic one can be found in the Menorah Journal between 1915 and 1925. During this time contributors to the Menorah promoted a cultural, rather than a racial, religious, or other view of Jewishness as a means to define Jews in a world that threatened to overwhelm and absorb Jewish uniqueness. The journal represented the ideals of the menorah movement established by Horace Kallen and others to promote a revival in Jewish cultural identity and combat the idea of race as a means to define or identify peoples.[63]

Siporin (1990) uses the family folklore of ethnic Jews to their collective history and its transformation into an historical art form. They tell us how Jews have survived being uprooted and transformed. Many immigrant narratives bear a theme of the arbitrary nature of fate and the reduced state of immigrants in a new culture. By contrast, ethnic family narratives tend to show the ethnic more in charge of his life, and perhaps in danger of losing his Jewishness altogether. Some stories show how a family member successfully negotiated the conflict between ethnic and American identities.[64]

After 1960 memories of the Holocaust, together with the Six-Day War in 1967 that resulted in the survival of Israel had major impacts on fashioning Jewish ethnic identity. The Shoah provided Jews with a rationale for their ethnic distinction at a time when other minorities were asserting their own.[65]

Antisemitism in the United States

Anti-Jewish sentiment started around the time of the American Civil War, when General Ulysses S. Grant issued an order (quickly rescinded by President Abraham Lincoln) of expulsion against Jews from the portions of Tennessee, Kentucky and Mississippi under his control. (See General Order No. 11)

Antisemitism continued into the first half of 20th century. Jews were discriminated against in some employment, not allowed into some social clubs and resort areas, given a quota on enrollment at colleges, and not allowed to buy certain properties.

Antisemitism in America reached its peak during the interwar period. The rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, the antisemitic works of Henry Ford, and the radio speeches of Father Coughlin in the late 1930s indicated the strength of attacks on the Jewish community.

Antisemitism in the United States has rarely turned into physical violence against Jews. Some more notable cases of such violence include the attack of Irish workers and police on the funeral procession of Rabbi Jacob Joseph in New York City in 1902, the lynching of Leo Frank in 1915, the murder of Alan Berg in 1984, and the Crown Heights riots of 1991.

Following the Second World War and the American Civil Rights Movement, anti-Jewish sentiment waned. Some members of the Black Nationalist Nation of Islam claimed that Jews were responsible for the exploitation of black labor, bringing alcohol and drugs into their communities, and unfair domination of the economy. Furthermore, according to surveys begun in 1964 by the Anti-Defamation League, a Jewish organization, African Americans are significantly more likely than white Americans to hold antisemitic beliefs, although there is a strong correlation between education level and the rejection of antisemitic stereotypes for all races. However, black Americans of all education levels are nevertheless significantly more likely than whites of the same education level to be antisemitic. In the 1998 survey, blacks (34%) were nearly four times as likely as whites (9%) to fall into the most antisemitic category (those agreeing with at least 6 of 11 statements that were potentially or clearly antisemitic). Among blacks with no college education, 43% fell into the most antisemitic group (vs. 18% for the general population), which fell to 27% among blacks with some college education, and 18% among blacks with a four-year college degree (vs. 5% for the general population).[66]

The 2005 Anti-Defamation League survey includes data on Hispanic attitudes, with 29% being most antisemitic (vs. 9% for whites and 36% for blacks); being born in the United States helped alleviate this attitude: 35% of foreign-born Hispanics, but only 19% of those born in the US.[67]

Religious tensions continued to exist in the United States, but numerous polls indicated that Jews were no longer the focus of hostility, and indeed that antisemitism is at a low point in the U.S.[citation needed] As an example of religious tension, in 2010 widespread debate erupted over building an Islamic cultural center and mosque in New York City near the World Trade Center site. The city of New York has officially endorsed the project, but public opinion nationwide has been hostile. A Time (magazine) poll in August 2010 of 1000 individuals indicated that 13 percent hold unfavorable views of Jews, compared with 43 percent who had unfavorable views of Muslims, 17 percent who felt unfavorably toward Catholics and 29 percent who viewed Mormons unfavorably.[68][69] By contrast, antisemitic attitudes are much higher in Europe and are growing.[70]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ Sarna (2004) 356-60

- ^ Hasia Diner, The Jews of the United States (2004)

- ^ Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews, p.366

- ^ See

- ^ Charleston, S.C.

- ^ [1] [2] and [3] and [4]

- ^ Charleston, S.C.

- ^ See 1, 2, etc.

- ^ "Our Story". Jews In America. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- ^ "A "portion of the People"", Nell Porter Brown, Harvard Magazine, January-February, 2003

- ^ David Salisbury Franks

- ^ Alexander DeConde, Ethnicity, Race, and American Foreign Policy: A History, p.52

- ^ Jonathan Sarna, American Judaism (2004) ch. 2 and p. 374

- ^ a b "Jewish Texans". Texancultures.utsa.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- ^ ["The Jewish Americans" Dir. David Grubin. PBS Home Video, 2008. Disc 1, Episode 1, Chapter 5, 0:30:40]

- ^ Perednik, Gustavo. "Judeophobia - History and analysis of Antisemitism, Jew-Hate and anti-"Zionism"".

- ^ Hardwick (2002), pg. 13

- ^ Hal Rothman, "’Same Horse, New Wagon’: Tradition and Assimilation among the Jews of Wichita, 1865-1930." Great Plains Quarterly 1995 15(2): 83-104. 0275-7664

- ^ William M. Kramer, "The Emergence of Oakland Jewry." Western States Jewish Historical Quarterly 1978 10 (2): 99-125, (3): 238-259, (4): 353-373; 11(1): 69-86; 1979 11(2): 173-186, (3): 265-278. 0043-4221

- ^ Evyatar Friesel, "Jacob H. Schiff and the Leadership of the American Jewish Community. Jewish Social Studies 2002 8(2-3): 61-72. 0021-6704

- ^ Seth Korelitz, "'A Magnificent Piece of Work': the Americanization Work of the National Council of Jewish Women." American Jewish History 1995 83(2): 177-203.

- ^ Diner, The Jews of the United States 135-40, 173-82

- ^ The Foundation gave away all its money and closed down in 1948. Lawrence P. Bachmann, "Julius Rosenwald," American Jewish Historical Quarterly 1976 66(1): 89-105; Peter M. Ascoli, Julius Rosenwald (2006)

- ^ David S. Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941-1945 (New York, 1984), p. 5.

- ^ Charles Stember, ed. (1966). Jews in the Mind of America. pp. 53–62.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "The American Experience.America and the Holocaust.People & Events | Breckinridge Long (1881 -1958)". PBS. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- ^ Henry L. Feingold, A Time for Searching: Entering the Mainstream, 1920–1945 (1992), pp 225–65

- ^ Deborah Lipstadt, Beyond Belief: The American Press and the Coming of the Holocaust (1993),

- ^ Laurel Leff, Buried by The Times: The Holocaust and America's Most Important Newspaper (Cambridge University Press, 2005)

- ^ Laurel Leff, "A Tragic 'Fight In The Family': The New York Times, Reform Judaism and the Holocaust." American Jewish History 2000 88(1): 3-51. 0164-0178

- ^ Felicia Herman, "Hollywood, Nazism, and the Jews, 1933–41." American Jewish History 2001 89(1): 61–89; Joyce Fine, "American Radio Coverage of the Holocaust," Simon Wiesenthal Center Annual 1988 5: 145–165. 0741-8450.

- ^ Davis S. Wyman Institute; New York Times (NYT)

- ^ Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life (2000)

- ^ Staub (2004) p.80

- ^ Sarna, American Judaism (2004) p 284-5

- ^ a b c d Jonathan D. Sarna and Jonathan Golden. "The American Jewish Experience in the Twentieth Century: Antisemitism and Assimilation".

- ^ a b Hasia Diner, The Jews of the United States. 1654 to 2000 (2004), ch 5

- ^ Steve Fraser, Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor (1993)

- ^ Ronald H. Bayor, Neighbors in Conflict: The Irish, Germans, Jews and Italians of New York City, 1929-1941, (1978)

- ^ See Murray Friedman, What Went Wrong? The Creation and Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance. (1995)

- ^ Joshua M. Zeitz, White Ethnic New York: Jews, Catholics, and the Shaping of Postwar Politics (2007).

- ^ a b c d e f "Jewish Vote In Presidential Elections". American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ^ Abba Hillel Silver

- ^ Mark R. Levy and Michael S. Kramer, The Ethnic Factor (1973) p. 103

- ^ Sandy Maisel and Ira Forman, eds. Jews in American Politics (2001)

- ^ See American Jewish Historical Society "2010 Scholars Conference"

- ^ Marc Dollinger, "American Jewish Liberalism Revisited: Two Perspectives Exceptionalism and Jewish Liberalism." American Jewish History v 30#2 2002. pp 161+. online at Questia

- ^ a b Staub (2004)

- ^ Staub (2004) p. 90

- ^ Plaskow, Judith. "Jewish Feminist Thought" in Frank, Daniel H. & Leaman, Oliver. History of Jewish Philosophy, Routledge, first published 1997; this edition 2003.

- ^ Henry L. Feingold, Silent No More': Saving the Jews of Russia, the American Jewish Effort, 1967-1989 (2007)

- ^ Fred A. Lazin, "'Freedom of Choice': Israeli Efforts to Prevent Soviet Jewish Emigres to Resettle in the United States," Review of Policy Research 2006 23(2): 387-411 in EBSCO

- ^ Annelise Orleck, The Soviet Jewish Americans (1999)

- ^ Rob Spinney, "The Jewish Community in Nashville, 1939-1949." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 1993 52(4): 225-241. 0040-3261

- ^ Christopher Ogden, Legacy: A Biography of Moses and Walter Annenberg (1999)

- ^ Amy Klein, "Seniors Opting to Go West, Build New Jewish Life," JewishJournal.com May 20, 2009

- ^ Deborah Dash Moore, To the Golden Cities: Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A. (1994); Stephen J. Whitfield, "Blood and Sand: the Jewish Community of South Florida." American Jewish History 1994 82(1-4): 73-96. 0164-0178

- ^ Marianne Sanua, "Stages in the Development of Jewish Life at Princeton University," American Jewish History 1987 76(4): 391-415. 0164-0178

- ^ David Brooks, "The Tel Aviv Cluster," New York Times January 11, 2010

- ^ From national exit polls, [5] and [6]

- ^ For a dissenting opinion, see Jonathan D. Sarna, American Judaism: A History (2004), who sees American Jewish history primarily in religious terms: "a story of people who lose their faith and a story of people who regain their faith," (p. xiv)

- ^ Eli Lederhendler, "The New Filiopietism, or toward a New History of Jewish Immigration to America," American Jewish History Volume: 93#1 2007. pp 1+. online edition

- ^ Seth Korelitz, "The Menorah Idea: From Religion to Culture, From Race to Ethnicity," American Jewish History 1997 85(1): 75–100. 0164-0178

- ^ Steve Siporin, "Immigrant and Ethnic Family Folklore," Western States Jewish History 1990 22(3): 230–242. 0749-5471

- ^ Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life (1999); Hilene Flanzbaum, ed. The Americanization of the Holocaust (1999); Monty Noam Penkower, "Shaping Holocaust Memory," American Jewish History 2000 88(1): 127–132. 0164-0178

- ^ Anti-Defamation League Survey [7].

- ^ Anti-Defamation League Survey [8].

- ^ Wednesday, Aug. 18, 2010 (2010-08-18). "Poll Results: Americans' Views on the Campaign, Religion and the Mosque Controversy". TIME. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ By Reuters. "Poll: Anti-Semitic views in the U.S. at a historic low - Haaretz Daily Newspaper | Israel News". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Kohut, Andrew (2008-10-30). "Xenophobia on the Continent - Pew Research Center". Pewresearch.org. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

Further reading

Surveys

- The Jewish People in America 5 vol 1992

- Faber, Eli. A Time for Planting: The First Migration, 1654-1820 (Volume 1) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Diner, Hasia A. A Time for Gathering: The Second Migration, 1820-1880 (Volume 2) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Sorin, Gerald. A Time for Building: The Third Migration, 1880-1920 (1992) excerpt and text search

- Feingold, Henry L. A Time for Searching: Entering the Mainstream, 1920-1945 (Volume 4) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Shapiro, Edward S. A Time for Healing: American Jewry since World War II, (Volume 5) (1992) excerpt and text search

- Diner, Hasia. Jews in America (1999) online edition

- Diner, Hasia. The Jews of the United States, 1654-2000 (2006) excerpt and text search, standard scholarly history online edition

- Diner, Hasia. A New Promised Land: A History of Jews in America (2003) excerpt and text search; online edition

- Feingold, Henry L. Zion in America: The Jewish Experience from Colonial Times to the Present (1974) online

- Glazer, Nathan. American Judaism (1957, revised 1972), classic in sociology

- Heilman, Samuel C. Portrait of American Jews: The Last Half of the 20th Century (1995) online edition

- Hyman, Paula E., and Deborah Dash Moore, eds. Jewish Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, 2 vol. (1997).

- Kaplan, Dana Evan, ed. The Cambridge Companion to American Judaism (2005)

- Norwood, Stephen H., and Eunice G. Pollack, eds. Encyclopedia of American Jewish history (2 vol ABC-CLIO, 2007), 775pp; comprehensive coverage by experts; excerpt and text search vol 1

- Sarna, Jonathan D. American Judaism: A History (2004), standard scholarly history

Specialty topics

- Abramovitch, Ilana and Galvin, Sean, eds. Jews of Brooklyn. (2002). 400 pp.

- Cutler, Irving. The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb. (1996)

- Dalin, David G. and Kolatch, Alfred J. The Presidents of the United States and the Jews. (2000)

- Diner, Hasia R. and Benderly, Beryl Lieff. Her Works Praise Her: A History of Jewish Women in America from Colonial Times to the Present. (2002). 462 pp. online edition

- Dollinger, Marc. Quest for Inclusion: Jews and Liberalism in Modern America. (2000). 296 pp. online edition

- Howe, Irving. World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made (1976) excerpt and text search, classic account; exaggerates importance of Yiddish culture and socialism; neglects role of religion

- Jick, Leon. The Americanization of the Synagogue, 1820-1870 (1976)

- Kaplan, Dana Evan. American Reform Judaism: An Introduction (2003) online edition

- Karp, Abraham, ed. The Jews in America: A Treasury of Art and Literature. Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, (1994)

- Linzer, Norman, et al. A Portrait of the American Jewish Community (1998) online edition

- Maisel, Sandy, and Ira Forman, eds. Jews in American Politics (2001), with voting statistics on p. 153

- Moore, Deborah Dash. GI Jews: How World War II Changed a Generation (2006)

- Moore, Deborah Dash. At Home in America: Second Generation New York Jews. (1981).

- Morowska, Ewa. Insecure Prosperity: Small-Town Jews in Industrial America, 1890-1940 (1996)

- Neu, Irene D. "The Jewish Businesswoman in America." American Jewish Historical Quarterly 66 (1976–1977): 137-153.

- Silverstein, Alan. Alternatives to Assimilation: The Response of Reform Judaism to American Culture, 1840-1930. (1994). 275 pp.

- Staub, Michael E. Torn at the Roots: The Crisis of Jewish Liberalism in Postwar America. (2002). 392 pp. online edition

- Whitfield, Stephen J. In Search of American Jewish Culture. (1999). 307 pp.

- Wirth-Nesher, Hana, and Michael P. Kramer. The Cambridge Companion to Jewish American Literature (2003) online edition

Primary sources

- "The Jews: Next Year in Which Jerusalem" Time April 10, 1972, online

- Salo Wittmayer Baron and Joseph L. Blau, eds. The Jews of the United States, 1790-1840: A Documentary History. 3 vol.(1963) online

- Farber, Roberta Rosenberg, and Chaim I. Waxman, eds. Jews in America: A Contemporary Reader (1999) excerpt and text search

- Gurock, Jeffrey S., ed. American Jewish History series

- The Colonial and Early National Periods, 1654-1840. , vol. 1 (1998). 486 pp.

- Central European Jews in America, 1840-1880: Migration and Advancement. vol. 2. (1998). 392 pp.

- East European Jews in America, 1880-1920: Immigration and Adaptation. vol. 3. (1998). 1295 pp.

- American Jewish Life, 1920-1990. vol. 4. (1998). 370 pp.

- Transplantations, Transformations, and Reconciliations. vol. 5. (1998). 1375 pp.

- Anti-Semitism in America. vol. 6. (1998). 909 pp.

- America, American Jews, and the Holocaust. vol. 7 (1998). 486 pp.

- American Zionism: Mission and Politics. vol. 8. (1998). 489 pp.

- Irving Howe and Kenneth Libo, eds. How We Lived, 1880-1930: A Documentary History of Immigrant Jews in America (1979) online

- Marcus, Jacob Rader, ed. The Jew in the American World: A Source Book (1996.)

- Staub, Michael E. ed. The Jewish 1960s: An American Sourcebook University Press of New England, 2004; 371 pp. ISBN 1-58465-417-1 online review

External links

- Davis S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies; "A Thanksgiving Day when Jews Mourned.", copyright 2005. accessed 7 September 2006.

- New York Times (NYT), October 15, 1943; p. 21; "Moves for Admission of 100,000 Refugees - Barbour Offers Resolution for Entry of Racial Victims"; accessed December 12, 2006 (There may be a charge for this article if accessed online.)

External links and references

- Jewish American History

- online Jewish encyclopedia

- American Jewish Historical Society - Chapters in American Jewish History

- Presidential speech (Ronald Reagan, Apr 12, 1984), reading report of (Jewish) Navy Chaplain Arnold E. Resnicoff, present at the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing: unique occasion of a U.S. President reading a rabbi's words: Text version of speech; Video version of that speech