Dress code: Difference between revisions

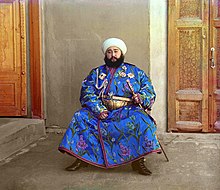

→Private dress codes: photo description |

|||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

==Private dress codes== |

==Private dress codes== |

||

[[Image:LondonClubDressCode.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''Dress code for a |

[[Image:LondonClubDressCode.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''Dress code for a private club in [[Soho]], [[London]].'']] |

||

Dress codes may be enforced by private entities, usually imposing a particular requirement for entry into a private space. "Dress code" may also refer to a social norm. |

Dress codes may be enforced by private entities, usually imposing a particular requirement for entry into a private space. "Dress code" may also refer to a social norm. |

||

Revision as of 04:04, 1 May 2006

This article needs additional citations for verification. |

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. |

Clothing, like other aspects of human physical appearance, has various social aspects.

Wearing specific types of clothing or the manner of wearing clothing can have the deliberate purpose, or the desirable or undesirable side-effect, to correctly or incorrectly be interpreted in terms of social class, income, occupation, ethnic and religious affiliation, attitude, marital status, sexual availability, and sexual orientation. This may be considered a "social message", even if it is not deliberate. If the "code of interpretation" applied by the receiver differs from the "sending code", this may give misinterpretations.

The manner of consciously constructing, assembling, and wearing clothing to convey a social message in any culture is governed by current fashion. The rate at which fashion changes varies; easily modified styles in wearing or accessorizing clothes can change in months, even days, in small groups or in media-influenced modern societies. More extensive changes, that may require more time, money, or effort to effect, may span generations. When fashion changes, messages from clothing change.

For example, wearing expensive clothes can be due to (a combination of)

- Being wealthy

- preferring to spend more money on clothing

- Managing to obtain clothing cheaper than usual

An observer can see the resultant, expensive clothes, but may be wrong about the extent to which these factors apply. See also conspicuous consumption. All factors apply inversely for wearing inexpensive clothing, and similarly for other goods.

Other messages clothing can give:

- Stating or claiming identity

- Establishing, maintaining and defying social group norms

Social status

In many societies, people of high rank reserve special items of clothing or decoration for themselves as symbols of their social status. In ancient times, only Roman senators could wear garments dyed with Tyrian purple; only high-ranking Hawaiian chiefs could wear feather cloaks and palaoa or carved whale teeth. In China before the establishment of the republic, only the emperor could wear yellow. In many cases throughout history, there have been elaborate systems of sumptuary laws regulating who could wear what. In other societies (including most modern societies), no laws prohibit lower-status people from wearing high-status garments, but the high cost of status garments effectively limits purchase and display. In current Western society, only the rich can afford haute couture. The threat of social ostracism may also limit garment choice.

Occupation

Military, police, and firefighters usually wear uniforms, as do workers in many industries. School children often wear school uniforms, while college and university students sometimes wear academic dress. Members of religious orders may wear uniforms known as habits. Sometimes a single item of clothing or a single accessory can declare one's occupation or rank within a profession — for example, the high toque or chef's hat worn by a chief cook.

See also undercover.

Ethnic, political, and religious affiliation

In many regions of the world, national costumes and styles in clothing and ornament declare membership in a certain village, caste, religion, etc. A Scotsman declares his clan with his tartan. A Sikh may display his religious affiliation by wearing a turban and other traditional clothing. A French peasant woman may identify her village with her cap or coif.

Clothes can also proclaim dissent from cultural norms and mainstream beliefs, as well as personal independence. In 19th-century Europe, artists and writers lived la vie de Bohème and dressed to shock: George Sand in men's clothing, female emancipationists in bloomers, male artists in velvet waistcoats and gaudy neckcloths. Bohemians, beatniks, hippies, Goths, Punks and Skinheads have continued the (countercultural) tradition in the 20th-century West. Now that haute couture plagiarizes street fashion within a year or so, street fashion may have lost some of its power to shock, but it still motivates millions trying to look hip and cool.

Marital status

Hindu women, once married, wear sindoor, a red powder, in the parting of their hair; if widowed, they abandon sindoor and jewelry and wear simple white clothing. Men and women of the Western world may wear wedding rings to indicate their marital status. See also Visual markers of marital status.

Sexual interest

Some clothing indicates the modesty of the wearer. For example, many Muslim women wear head or body covering (see hijab, burqa or bourqa, chador and abaya) that proclaims their status as respectable women. Other clothing may indicate flirtatious intent. For example, a Western woman might wear extreme stiletto heels, close-fitting and body-revealing black or red clothing, exaggerated make-up, flashy jewelry and perfume to show sexual interest. A man might wear a tightly-cut shirt and unbutton the top buttons.

What constitutes modesty and allurement varies radically from culture to culture, within different contexts in the same culture, and over time as different fashions rise and fall. Moreover, a person may choose to display a mixed message. For example, a Saudi Arabian woman may wear an abaya to proclaim her respectability, but choose an abaya of luxurious material cut close to the body and then accessorize with high heels and a fashionable purse. All the details proclaim sexual desirability, despite the ostensible message of respectability.

Sexual orientation

Clothing can also be used as a public signal of sexual orientation.

Gay pride-themed clothing or decorations, including symbols such as the rainbow flag, or the logo of the Human Rights Campaign, are fairly obvious choices for someone wishing to indicate that they are not straight. However, heterosexual gay rights supporters may also choose to display such symbols as a political statement, which leads to some possibility for ambiguity.

T-shirts with printed slogans or icons have also become somewhat popular for use in casual social situations, and are offered for sale at many LGBT-oriented clothing stores. They often include witty sexual innuendo, comical expressions of affection for people of a particular gender, or non-sexual use of gay slang.

Sometimes people make fashion choices for or against a particular look based on whether or not it "looks gay" (depending on what type of signal they wish to send). Stereotypically "gay" fashion choices include dressing against prevailing gender norms (for example, a trucker's hat for a lesbian, or a pink short for a gay man), and for gay men, looking "fashionable" or well-kept. While some people do exploit these stereotypes, many people either ignore them in their fashion choices, intentionally avoid them, or are unaware of them. General erosion of traditional gender norms (see for example, metrosexual) and the ambiguity and changing standards of fashion contributes to the unreliability of determining a person's sexual orientation based on these stereotypes, and some people would consider it offensive to try. Members of some local LGBT communities do seem to try to differentiate themselves as a group, but the particulars vary by location, and can be difficult to detect (especially given integration with the surrounding culture).

Clothing can also be used to express interest in a particular sexual activity or role. One trend in the 2000s is a line of T-shirts that has iconic 1950-style depictions of the baseball positions pitcher and catcher, which are intended to correspond to the top and bottom sexual positions. An older example is the handkerchief code used in the BDSM subculture.

Laws and social norms

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

In Tonga it is illegal for men to appear in public without shirt.

In New Guinea, men wear nothing but penis sheaths in public. Women wear string skirts. In Bali, women go topless. In India, women can show belly but not legs.

In the island of Bermuda there is a strict dress code, such that restaurants are designated with different dress-code levels such as "business casual" or "casual." It is also illegal to not wear a shirt or shoes on any of the public places on the island with the exception of the beach.

Private dress codes

Dress codes may be enforced by private entities, usually imposing a particular requirement for entry into a private space. "Dress code" may also refer to a social norm.

- By religious law or tradition

- For employees, pupils/students, etc. - sometimes a uniform; sometimes depending on the day, see Casual Friday; see also International standard business attire

- For customers, e.g. for a disco, nightclub, casino, shop or restaurant

- In special parties; sometimes a specific costume is requested

- As social rules in general

Dress codes function on certain social occasions and for certain jobs. A school or a military institution may require specified uniforms; if it allows the wearing of plain clothes it may place restrictions on their use. A bouncer of a disco or nightclub may judge visitors' clothing and refuse entrance to those not clad according to specified or intuited requirements.

Some dress codes specify that tattoos have to be covered.

A formal or white tie dress code typically means tail-coats for men and full-length evening dresses for women. Semi-formal has a much less precise definition but typically means an evening jacket and tie for men (known as black tie) and a dress for women. Lounge suit also known as Business casual typically means not wearing jeans or track suits, but wearing instead collared shirts, and more country trousers (not black, but more relaxed, including things such as corduroy). Casual typically just means clothing for the torso, legs and shoes.

Transparent or semi-transparent clothing can play with the boundaries of dress-codes regarding modesty, for example: in a wet T-shirt contest.

Dress codes usually set forth a lower bound on body covering. However, sometimes it can specify the opposite, for example, in UK gay jargon, dress code, means people who dress in a militaristic manner. Dress code nights in nightclubs, and elsewhere, are deemed to specifically target people who have militaristic fetishes (e.g. leather/skinhead men).

Setting a dress code can often lead to great embarrassment. One particularly famous example is that of UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, who asked the Bank of England's board to wear lounge suits to their annual dinner, a highly prestigious occasion, as an act of modernism in tune with New Labour thinking (they usually wore White Tie). However, he had not reckoned with their determination not to kow-tow, and when sat at dinner, he was the only person not dressed in White Tie.

See also shoe etiquette, mourning, sharia.

Company/Employer Dress Code Policy

Many employers mistakenly believe that discrimination laws restrict their right to determine appropriate workplace dress. In fact, employers can actually have a lot of discretion in what they can require their employees to wear to work. Generally, a carefully drafted dress code that is applied consistently should not violate discrimination laws. However, this fact will not stop employees from questioning company dress code policies. The following article examines common legal challenges to dress codes and suggests ways you can avoid problems. URL: http://www.ppspublishers.com/biz/dresscode.htm

Inverse dress codes

Inverse dress codes, sometimes referred to as "undress code", set forth an upper bound, rather than a lower bound, on body covering. An example of an undress code, is the one commonly enforced in modern communal bathing facilities. For example, in Schwaben Quellen no clothing of any kind is allowed. Other less strict undress codes are common in public pools, especially indoor pools, in which shoes and shirts are not allowed.

Places where nudism is practised may be "clothing optional", or nudity may be compulsory, with exceptions, see manners in nudism.

Gender and clothing

Various traditions suggests that certain items of clothing intrinsically suit different gender roles. In particular, the wearing of skirts and trousers has given rise to common phrases expressing implied restrictions in use and disapproval of offending behaviour. For example, ancient Greeks often considered the wearing of trousers by Persian men as a sign of effeminacy.

See also cross-dressing.

Violation of clothing taboos

Some clothing faux pas may occur intentionally for reasons of fashion or personal preference. For example, people may wear intentionally oversized clothing. For instance, the teenage boys of rap duo Kris Kross wore all of their clothes backwards and extremely baggy.

A common deliberate violation of clothing taboos is the removal of the shirt, together with pulling down the pants to show the underpants

The trend in underwear has moved toward underwear that looks less like underwear, e.g. instead of white briefs that say "Mr Brief" or "Fruit of the Loom" in large letters around the waistband, trends have shifted toward undergarments that look like bathing suits or beach shorts. However, some people are going back to the plain white underwear with bold underwearlike lettering around the waistband, i.e. familiar underwear brand names around the waistband, to enhance the violation of the taboo against showing underwear as a fashion statement. For women, deliberately showing bra straps has also become fashionable.

Mooning is the deliberate baring of the buttocks as a gesture of teasing or contempt.

Underwearing

See also underwearing.

Some people strip down to their underwear as a fashion statement, as a form of protest, or to get attention (i.e. for advertisement), in cases where one does not want to go as far as being nude. As a fashion statement, Tommy Hilfiger ran a series of large billboard advertisements showing mixed-gender groups wearing only their underwear in public. For example, groups were shown at outdoor splash areas, frolicking in nothing but their underwear. This implied a certain spontaneity, as one might find at an urban beach where people decide to strip to their underwear to cool off in a fountain on a hot summer day. Traditionally, people would need a bathing suit, but because of the popularization of underwearing, the taboo against showing underwear has been weakened, and in some ways reversed, making the showing of underwear actually fashionable.

Some groups protesting against fur have adopted the phrase "I'd rather be in my underwear than wear fur". Members may confirm their words by stripping to their underwear in public.

As a form of attention-getting, freshpair.com has created "National Underwear Day" and had large numbers of models walk through Times Square wearing nothing but their underwear. This helped to draw tremendous attention to the day and to freshpair.com.

Reversalism in the sociology of clothing

Social attitudes to clothing have brought about various rules and social conventions, such as keeping the body covered, and not showing underwear in public. The backlash against these social norms has become a traditional form of rebellion.

Nudity and contamination

During the 2001 anthrax attacks, large numbers of people stripped to their underwear in parking lots and other public places, for hosing down by fire departments, often in front of TV news crews covering the events.

On the other hand, some people are unwilling to violate their self-imposed and fully internalized social norms of body covering, even in a situation where mass stripdowns and washdowns could save their lives.