Harakiri (1962 film): Difference between revisions

Marc Kupper (talk | contribs) m →Plot: wlink |

→Themes: mark as possible OR |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

==Themes== |

==Themes== |

||

{{original research|section}} |

|||

The film presents a negative view of the emerging feudal system at the beginning of the 17th century, depicting the [[hypocrisy]] in the flimsy pretext of honor exhibited by the ''[[daimyo]]''. At the time, ''seppuku'' was seen as a means to retain one's honor after a disgrace.{{citation needed|date=February 2013}} The vanity of the feudal lord's counsellor Saitō is also shown: the outward appearance of honour is shown to be more important to him than real honour. He orders the retainers disgraced by Hanshirō to perform ''seppuku'', and makes sure that those who were slain or had their topknots cut off by Hanshirō are written off as casualties to illness so that his house would not appear weak. An ironic commentary appears when Hanshirō is able to fight off a great many retainers with a sword, yet is helpless against three guns; a foreshadow of the [[Meiji Restoration]], wherein sword-bearing samurai were defeated by the "new" Japanese military. |

The film presents a negative view of the emerging feudal system at the beginning of the 17th century, depicting the [[hypocrisy]] in the flimsy pretext of honor exhibited by the ''[[daimyo]]''. At the time, ''seppuku'' was seen as a means to retain one's honor after a disgrace.{{citation needed|date=February 2013}} The vanity of the feudal lord's counsellor Saitō is also shown: the outward appearance of honour is shown to be more important to him than real honour. He orders the retainers disgraced by Hanshirō to perform ''seppuku'', and makes sure that those who were slain or had their topknots cut off by Hanshirō are written off as casualties to illness so that his house would not appear weak. An ironic commentary appears when Hanshirō is able to fight off a great many retainers with a sword, yet is helpless against three guns; a foreshadow of the [[Meiji Restoration]], wherein sword-bearing samurai were defeated by the "new" Japanese military. |

||

Revision as of 08:26, 5 August 2013

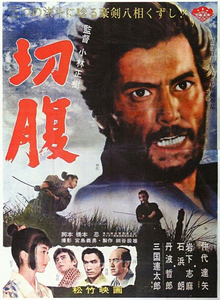

| Harakiri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Masaki Kobayashi |

| Written by | Shinobu Hashimoto Yasuhiko Takiguchi |

| Produced by | Tatsuo Hosoya |

| Starring | Tatsuya Nakadai Rentarō Mikuni Shima Iwashita Akira Ishihama |

| Music by | Tōru Takemitsu |

| Distributed by | Shochiku |

Release date | September 16, 1962 (Japan) |

Running time | 133 min. |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Harakiri (切腹, Seppuku, 1962) is a Japanese jidaigeki (period-drama) film directed by Masaki Kobayashi. The story takes place between 1619 and 1630 during the Edo period and the reign of the Tokugawa shogunate. It tells the story of Hanshirō Tsugumo, a rōnin or warrior without a lord.

Plot

On May 16, 1630, Tsugumo Hanshirō arrives at the estate of the Ii clan, looking for a suitable place to perform seppuku. At the time, it is told, it was fairly common for disgraced samurai to make the same request, or threat, in the hope of receiving alms from the lord of the house. To deter him Saitō Kageyu (Rentarō Mikuni), counselor of the clan, tells Hanshirō a warning story wherein another rōnin, Chijiiwa Motome – formerly of the same clan as Hanshirō – had made the same request and the samurai retainers of the house forced him to complete the ceremony and kill himself. When Motome's sword is revealed to be a fake made of bamboo, they refuse to give him a blade and insist that he disembowel himself with the bamboo sword, so that Motome's death is agonizingly painful. Despite this warning, Hanshirō maintains his request to commit suicide.

While preparing for the ritual, Hanshirō recounts to Saitō and the retainers that his lord's house was considered a threat and toppled by the shogunate, whereupon his friend, another samurai, performed seppuku and left Hanshirō to look after his son, Chijiiwa Motome. Required to protect Motome and support his own daughter Miho, Hanshirō lived in poverty and worked menial jobs to support his family. In later years Motome and Miho were married and had a son, Kingo, but continued to live in poverty. When Miho and Kingo became ill and could not afford to pay a physician, Motome threatened seppuku at a lord's house. Soon after his seppuku, Miho and Kingo died from their illnesses.

Hanshirō then reveals that before coming to the Ii house, he tracked down two retainers of the house, Yazaki Hayato and Kawabe Umenosuke, whom he defeated easily and disgraced by cutting off their topknots. A third retainer, Omodaka Hikokuro, comes to Hanshirō's home and challenges him to a ritual duel. Hanshirō and Hikokuro climatically duel in a brief but tense sword fight, where Hanshirō breaks Hikokuro's sword. Instead of honorably surrendering, Hikokuro continues to fight and his topknot is taken as well.

When Hanshirō finishes his account, Saitō angrily orders the retainers to kill him; whereupon Tsugumo kills four and wounds eight while slowly succumbing to his wounds. When a new group of retainers arrive armed with guns, Hanshirō begins seppuku but is shot. Kawabe and Yazaki are ordered to perform seppuku, while Hikokuro is reported to have done so already; their deaths, and the four inflicted by Hanshirō, are to be reported as from "illness," lest word be spread that the Ii house has lost face to a rōnin.

Main cast

- Tatsuya Nakadai - Tsugumo Hanshirō

- Rentarō Mikuni - Saitō Kageyu

- Shima Iwashita - Tsugumo Miho

- Akira Ishihama - Chijiiwa Motome

- Tetsurō Tamba - Omodaka Hikokuro

- Ichiro Nakaya - Yazaki Hayato

- Yoshio Aoki - Kawabe Umenosuke

Themes

This section possibly contains original research. |

The film presents a negative view of the emerging feudal system at the beginning of the 17th century, depicting the hypocrisy in the flimsy pretext of honor exhibited by the daimyo. At the time, seppuku was seen as a means to retain one's honor after a disgrace.[citation needed] The vanity of the feudal lord's counsellor Saitō is also shown: the outward appearance of honour is shown to be more important to him than real honour. He orders the retainers disgraced by Hanshirō to perform seppuku, and makes sure that those who were slain or had their topknots cut off by Hanshirō are written off as casualties to illness so that his house would not appear weak. An ironic commentary appears when Hanshirō is able to fight off a great many retainers with a sword, yet is helpless against three guns; a foreshadow of the Meiji Restoration, wherein sword-bearing samurai were defeated by the "new" Japanese military.

Reception

On February 23, 2012, Roger Ebert added 'Harakiri' to his list of "Great Movies". He writes "Samurai films, like westerns, need not be familiar genre stories. They can expand to contain stories of ethical challenges and human tragedy. Harakiri, one of the best of them, is about an older wandering samurai who takes his time to create an unanswerable dilemma for the elder of a powerful clan. By playing strictly within the rules of Bushido Code which governs the conduct of all samurai, he lures the powerful leader into a situation where sheer naked logic leaves him humiliated before his retainers."[1]

Awards

The film was entered in the competition category at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival. It lost the Palme d'Or to The Leopard, but received the Special Jury Award.[2]

Remakes

The movie was remade by Japanese director Takashi Miike as a 3D movie named Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai in 2011. It premiered at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.

Notes

References

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 23, 2012). "Honor, morality, and ritual suicide". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Harakiri". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

External links

- Harakiri at IMDb

- Harakiri at AllMovie

- Criterion Collection essay by Joan Mellen

- "切腹 (Seppuku)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-07-16.