Toxoplasmosis: Difference between revisions

Lulurascal (talk | contribs) →Psychiatric disorders: this section was getting very long, moved info to separate page. Although jocular, this association is being colloquially termed Crazy Cat Lady Syndrome. Until more medical term is coined, will use this |

|||

| Line 169: | Line 169: | ||

Most infected cats will shed oocysts only once in their lifetimes, for a period of about one to two weeks.<ref name=Elmore2010 /> Although this period of shedding is quite transient, millions of oocysts can be shed, with each oocyst capable of spreading and surviving for months.<ref name=Elmore2010 /> An estimated 1% of cats at any given time are actively shedding oocysts.<ref name=Dubey2008 /> |

Most infected cats will shed oocysts only once in their lifetimes, for a period of about one to two weeks.<ref name=Elmore2010 /> Although this period of shedding is quite transient, millions of oocysts can be shed, with each oocyst capable of spreading and surviving for months.<ref name=Elmore2010 /> An estimated 1% of cats at any given time are actively shedding oocysts.<ref name=Dubey2008 /> |

||

=== Marine mammals === |

=== Marine mammals === |

||

Revision as of 09:38, 23 August 2013

| Toxoplasmosis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases, obstetrics and gynaecology |

Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii.[1] The parasite infects most genera of warm-blooded animals, including humans, but the primary host is the felid (cat) family. Animals are infected by eating infected meat, by ingestion of feces of a cat that has itself recently been infected, and by transmission from mother to fetus. Cats are the primary source of infection to human hosts, although contact with raw meat, especially pork, is a more significant source of human infections in some countries. Fecal contamination of hands is a significant risk factor.[2]

Nicolle and Manceaux first described the organism in 1908, after they observed the parasites in the blood, spleen, and liver of a North African rodent, Ctenodactylus gondii. The parasite was named Toxoplasma (arclike form) gondii (after the rodent) in 1909. In 1923, Janku reported parasitic cysts in the retina of an infant who had hydrocephalus, seizures, and unilateral microphthalmia. Wolf, Cowan, and Paige (1937–1939) determined these findings represented the syndrome of severe congenital T. gondii infection.[2]

Up to a third of the world's human population is estimated to carry a Toxoplasma infection.[3][4] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes the overall seroprevalence in the United States as determined with specimens collected by the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999 and 2004 was found to be 10.8%, with seroprevalence among women of childbearing age (15 to 44 years) 11%.[5] Another study placed seroprevalence in the US at 22.5%.[4] The same study claimed a seroprevalence of 75% in El Salvador.[4] Official assessment in Great Britain places the number of infections at about 350,000 a year.[6]

During the first few weeks after exposure, the infection typically causes a mild, flu-like illness or no illness. However, those with weakened immune systems, such as those with AIDS and pregnant women, may become seriously ill, and it can occasionally be fatal.[citation needed] The parasite can cause encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and neurologic diseases, and can affect the heart, liver, inner ears, and eyes (chorioretinitis).[citation needed] Recent research has also linked toxoplasmosis with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia.[7] Numerous studies found a positive correlation between latent toxoplasmosis and suicidal behavior in humans.[8][9][10]

Signs and symptoms

Infection has two stages:

Acute toxoplasmosis

During acute toxoplasmosis, symptoms are often influenza-like: swollen lymph nodes, or muscle aches and pains that last for a month or more. Rarely will a human with a fully functioning immune system develop severe symptoms following infection. Young children and immunocompromised people, such as those with HIV/AIDS, those taking certain types of chemotherapy, or those who have recently received an organ transplant, may develop severe toxoplasmosis. This can cause damage to the brain (encephalitis) or the eyes (necrotizing retinochoroiditis). Infants infected via placental transmission may be born with either of these problems, or with nasal malformations, although these complications are rare in newborns. The toxoplasmic trophozoites causing acute toxoplasmosis are referred to as Tachyzoites, and are typically found in bodily fluids.

Swollen lymph nodes are commonly found in the neck or under the chin, followed by the axillae (armpits) and the groin. Swelling may occur at different times after the initial infection, persist, and/or recur for various times independently of antiparasitic treatment.[11] It is usually found at single sites in adults, but in children, multiple sites may be more common. Enlarged lymph nodes will resolve within one to two months in 60% of cases. However, a quarter of those affected take two to four months to return to normal, and 8% take four to six months. A substantial number (6%) do not return to normal until much later.[12]

Latent toxoplasmosis

It is easy for a host to become infected with Toxoplasma gondii and develop toxoplasmosis without knowing it. In most immunocompetent people, the infection enters a latent phase, during which only bradyzoites are present, forming cysts in nervous and muscle tissue. Most infants who are infected while in the womb have no symptoms at birth, but may develop symptoms later in life.[13]

Cutaneous toxoplasmosis

While rare, skin lesions may occur in the acquired form of the disease, including roseola and erythema multiforme-like eruptions, prurigo-like nodules, urticaria, and maculopapular lesions. Newborns may have punctate macules, ecchymoses, or “blueberry muffin” lesions. Diagnosis of cutaneous toxoplasmosis is based on the tachyzoite form of T. gondii being found in the epidermis. It is found in all levels of the epidermis, is about 6 μm by 2 μm and bow-shaped, with the nucleus being one-third of its size. It can be identified by electron microscopy or by Giemsa staining tissue where the cytoplasm shows blue, the nucleus red.[14]

Crazy Cat Lady Syndrome

Studies have shown the toxoplasmosis parasite may affect behavior and may present as or be a causative or contributory factor in various psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia.[15][16][17] This association is often jocularly termed Crazy Cat Lady Syndrome.[18]

Contrary evidence

Toxoplasma gondii is beneficial to mice with Alzheimer's disease. [19] Murine analogues to the Comt, DRD4 and DAT1 human genes also exist, and these genes are related to Alzheimer's disease.[20] DAT1, for example, encodes the neural membranes through which dopamine returns to the cell. DAT1 gene mutations are responsible for too rapid dopamine uptake, which results in deficiency in extracellular dopamine. Since T. gondii produces dopamine, it has a potential to overcome these gene-related disorders also in humans, mainly because the mechanisms encoded by Comt, DRD4, and DAT1 are both murine and human. Too fast DAT1 dopamine uptake is related to other neurological disorders [21][22] which can potentially benefit from T. gondii dopamine synthesis. It is an interesting open question whether mammals with DAT1 polymorphisms are genetically better adapted to T. gondii infection.

Examples of genetic factors in Parkinson's disease are LRRK2 mutations Gly2019Ser, I2020T, and others. Some evidence indicates exposure to pesticides causes Parkinson's disease[23] The disease presents when 80% of the neurons that produce dopamine in the substantia nigra die. This shortage of dopamine could be compensated by T. gondii, which is known to produce dopamine.

Diagnosis

Toxoplasmosis can be difficult to distinguish from primary central nervous system lymphoma, and as a result, the diagnosis is made by a trial of therapy (pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid (USAN: leucovorin)), followed by a brain biopsy if the drugs produce no effect clinically and no improvement on repeat imaging.

Detection of T. gondii in human blood samples may also be achieved by using the polymerase chain reaction.[24] Inactive cysts may exist in a host which would evade detection.

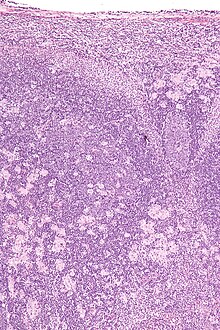

Toxoplasmosis cannot be detected with immunostaining. Lymph nodes affected by Toxoplasma have characteristic changes, including poorly demarcated reactive germinal centers, clusters of monocytoid B cells, and scattered epithelioid histiocytes.

Transmission

Transmission may occur through:

- Ingestion of raw or partly cooked meat, especially pork, lamb, or venison containing Toxoplasma cysts: Infection prevalence in countries where undercooked meat is traditionally eaten has been related to this transmission method. Tissue cysts may also be ingested during hand-to-mouth contact after handling undercooked meat, or from using knives, utensils, or cutting boards contaminated by raw meat.[25]

- Ingestion of contaminated cat feces: This can occur through hand-to-mouth contact following gardening, cleaning a cat's litter box, contact with children's sandpits, or touching a leech; the parasite can survive in the environment for over a year.[26]

Cats excrete the pathogen in their feces for a number of weeks after contracting the disease, generally by eating an infected rodent. Even then, cat feces are not generally contagious for the first day or two after excretion, after which the cyst 'ripens' and becomes potentially pathogenic.[27]

Pregnancy precautions

Congenital toxoplasmosis is a special form in which an unborn fetus is infected via the placenta. A positive antibody titer indicates previous exposure and immunity, and largely ensures the unborn fetus' safety. A simple blood draw at the first prenatal doctor visit can determine whether or not a woman has had previous exposure and therefore whether or not she is at risk. If a woman receives her first exposure to T. gondii while pregnant, the fetus is at particular risk. A woman with no previous exposure should avoid handling raw meat, exposure to cat feces, and gardening (cat feces are common in garden soil). Most cats are not actively shedding oocysts, so are not a danger, but the risk may be reduced further by having the litter box emptied daily (oocysts require longer than a single day to become infective), and by having someone else empty the litter box. However, while risks can be minimized, they cannot be eliminated. For pregnant women with negative antibody titers, indicating no previous exposure to T. gondii, serology testing as frequent as monthly is advisable as treatment during pregnancy for those women exposed to T. gondii for the first time decreases dramatically the risk of passing the parasite to the fetus.

Despite these risks, pregnant women are not routinely screened for toxoplasmosis in most countries (Portugal,[28] France,[29] Austria,[29] Uruguay,[30] and Italy[31] being the exceptions) for reasons of cost-effectiveness and the high number of false positives generated. As invasive prenatal testing incurs some risk to the fetus (18.5 pregnancy losses per toxoplasmosis case prevented),[29] postnatal or neonatal screening is preferred. The exceptions are cases where fetal abnormalities are noted, and thus screening can be targeted.[29]

Some regional screening programmes operate in Germany, Switzerland and Belgium.[31]

Treatment is very important for recently infected pregnant women, to prevent infection of the fetus. Since a baby's immune system does not develop fully for the first year of life, and the resilient cysts that form throughout the body are very difficult to eradicate with antiprotozoans, an infection can be very serious in the young.

In 2006, a Czech research team discovered women with high levels of toxoplasmosis antibodies were significantly more likely to have baby boys than baby girls. In most populations, the birth rate is around 51% boys, but women infected with T. gondii had up to a 72% chance of a boy.[32]

Rodent behavior

Infection with T. gondii has been shown to alter the behavior of mice and rats in ways thought to increase the rodents’ chances of being preyed upon by cats.[33][34][35] Infected rodents show a reduction in their innate aversion to cat odors; while uninfected mice and rats will generally avoid areas marked with cat urine or with cat body odor, this avoidance is reduced or eliminated in infected animals.[33][35][36] Moreover, some evidence suggests this loss of aversion may be specific to feline odors: when given a choice between two predator odors (cat or mink), infected rodents show a significantly stronger preference to cat odors than do uninfected controls.[37][38]

T. gondii-infected rodents show a number of behavioral changes beyond altered responses to cat odors. Rats infected with the parasite show increased levels of activity and decreased neophobic behavior.[34][39] Similarly, infected mice show alterations in patterns of locomotion and exploratory behavior during experimental tests. These patterns include traveling greater distances, moving at higher speeds, accelerating for longer periods of time, and showing a decreased pause-time when placed in new arenas.[40] Infected rodents have also been shown to have differences in traditional measures of anxiety, such as elevated plus mazes, open field arenas, and social interaction tests.[40][41]

Treatment

Treatment is often only recommended for people with serious health problems, such as people with HIV whose CD4 counts are under 200, because the disease is most serious when one's immune system is weak. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is the drug of choice to prevent toxoplasmosis, but not for treating active disease.

Acute

The medications prescribed for acute toxoplasmosis are:

- Pyrimethamine — an antimalarial medication

- Sulfadiazine — an antibiotic used in combination with pyrimethamine to treat toxoplasmosis

- Combination therapy is usually given with folic acid supplements to reduce incidence of thrombocytopaenia.

- Combination therapy is most useful in the setting of HIV.

- Clindamycin

- Spiramycin — an antibiotic used most often for pregnant women to prevent the infection of their children

(other antibiotics, such as minocycline, have seen some use as a salvage therapy).

Latent

In people with latent toxoplasmosis, the cysts are immune to these treatments, as the antibiotics do not reach the bradyzoites in sufficient concentration.

The medications prescribed for latent toxoplasmosis are:

- Atovaquone — an antibiotic that has been used to kill Toxoplasma cysts inside AIDS patients[42]

- Clindamycin — an antibiotic which, in combination with atovaquone, seemed to optimally kill cysts in mice[43]

Epidemiology

T. gondii infections occur throughout the world, although infection rates differ significantly by country.[44] For women of childbearing age, a survey of 99 studies within 44 countries found the areas of highest prevalence are within Latin America (about 50–80%), parts of Eastern and Central Europe (about 20–60%), the Middle East (about 30-50%), parts of Southeast Asia (about 20–60%), and parts of Africa (about 20–55%).[44]

In the United States, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2004 found 9.0% of US-born persons 12–49 years of age were seropositive for IgG antibodies against T. gondii, down from 14.1% as measured in the NHANES 1988–1994.[45] In the 1999–2004 survey, 7.7% of US-born and 28.1% of foreign-born women 15–44 years of age were T. gondii seropositive.[45] A trend of decreasing seroprevalence has been observed by numerous studies in the United States and many European countries.[44]

Because the parasite poses a particular threat to fetuses when it is contracted during pregnancy,[46] much of the global epidemiological data regarding T. gondii comes from seropositivity tests in women of childbearing age. Seropositivity tests look for the presence of antibodies against T. gondii in blood, so while seropositivity guarantees one has been exposed to the parasite, it does not necessarily guarantee one is chronically infected.[47]

History

The T. gondii protozoan was first discovered by Nicolle and Manceaux, who in 1908 isolated it from the African rodent Ctenodactylus gundi, then in 1909 differentiated the organism from Leishmania and named it Toxoplasma gondii.[29] The first recorded congenital case was not until 1923, and the first adult case not until 1940.[29] In 1948, a serological dye test was created by Sabin and Feldman, which is now the standard basis for diagnostic tests.[48]

Society and culture

Notable cases

- Arthur Ashe (tennis player) developed neurological problems from toxoplasmosis (and was later found to be HIV-positive).[49]

- Merritt Butrick (actor) was HIV positive and died from toxoplasmosis as a result of his already weakened immune system.[50]

- Prince François, Count of Clermont (pretender to the throne of France); his disability caused him to be overlooked in the line of succession.

- Leslie Ash (actress) contracted toxoplasmosis in the second month of pregnancy.[51]

- Sebastian Coe (British middle distance runner)[52]

- Martina Navratilova suffered from toxoplasmosis during the 1982 US Open.[53]

- Louis Wain (artist) was famous for painting cats; he later developed schizophrenia, which some believe was due to toxoplasmosis resulting from his prolonged exposure to cats.[54]

- Jaroslav Flegr (biologist) is a proponent of the theory that toxoplasmosis affects human behavior.[55]

Other animals

Although T. gondii has the capability of infecting virtually all warm-blooded animals, susceptibility and rates of infection vary widely between different genera and species.[56] Rates of infection in populations of the same species can also vary widely due to differences in location, diet, and other factors.

Livestock

Among livestock, pigs, sheep, and goats have the highest rates of chronic T. gondii infection.[57] The prevalence of T. gondii in meat-producing animals varies widely both within and between countries,[57] and rates of infection have been shown to be dramatically influenced by varying farming and management practices.[58] For instance, animals kept outdoors or in free-ranging environments are more at risk of infection than animals raised indoors or in commercial confinement operations.[58][59]

In the United States, the percentage of pigs harboring viable parasites has been measured (via bioassay in mice or cats) to be as high as 92.7% and as low as 0%, depending on the farm or herd.[59] Surveys of seroprevalence (T. gondii antibodies in blood) are more common, and such measurements are indicative of the high relative seroprevlance in pigs across the world.[60] Along with pigs, sheep and goats are among the most commonly infected livestock of epidemiological significance for human infection.[57] Prevalence of viable T. gondii in sheep tissue has been measured (via bioassay) to be as high as 78% in the United States,[61] and a 2011 survey of goats intended for consumption in the United States found a seroprevalence of 53.4%.[62]

Due to a lack of exposure to the outdoors, chickens raised in large-scale indoor confinement operations are not commonly infected with T. gondii.[58] Free-ranging or backyard-raised chickens are much more commonly infected.[58] A survey of free-ranging chickens in the United States found its prevalence to be 17%–100%, depending on the farm.[63] Because chicken meat is generally cooked thoroughly before consumption, poultry is not generally considered to be a significant risk factor for human T. gondii infection.[64]

Although cattle and buffalo can be infected with T. gondii, the parasite is generally eliminated or reduced to undetectable levels within a few weeks following exposure.[58] Tissue cysts are rarely present in buffalo meat or beef, and meat from these animals is considered to be low-risk for harboring viable parasites.[57][59]

Horses are considered resistant to chronic T. gondii infection.[58] However, viable cells have been isolated from US horses slaughtered for export, and severe human toxoplasmosis in France has been epidemiologically linked to the consumption of horse meat.[59]

Domestic cats

The seroprevalence of T. gondii in domestic cats, worldwide, has been estimated to be around 30–40%.[65] In the United States, no official national estimate has been made, but local surveys have shown levels varied between 16% and 80%.[65] A 2012 survey of 445 purebred pet cats and 45 shelter cats in Finland found an overall seroprevalence of 48.4%.[66] A 2010 survey of feral cats from Giza, Egypt, found an overall seroprevalence of 97.4%.[67]

T. gondii infection rates in domestic cats vary widely depending on the cats' diets and lifestyles.[68] Feral cats that hunt for their food are more likely to be infected than domestic cats. The prevalence of T. gondii in cat populations depends on the availability of infected birds and small mammals,[69] but often this prey is abundant.

Most infected cats will shed oocysts only once in their lifetimes, for a period of about one to two weeks.[65] Although this period of shedding is quite transient, millions of oocysts can be shed, with each oocyst capable of spreading and surviving for months.[65] An estimated 1% of cats at any given time are actively shedding oocysts.[58]

Marine mammals

A University of California, Davis study of dead sea otters collected from 1998 to 2004 found toxoplasmosis was the cause of death for 13% of the animals.[70] Proximity to freshwater outflows into the ocean was a major risk factor. Ingestion of oocysts from cat faeces is considered to be the most likely ultimate source.[71] Surface runoff containing wild cat faeces and litter from domestic cats flushed down toilets are possible sources of oocysts.[72] The parasites have been found in dolphins and whales.[17] Researchers Black and Massie believe anchovies, which travel from estuaries into the open ocean, may be helping to spread the disease.

See also

References

- ^ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 723–7. ISBN 0838585299.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Torda A (2001). "Toxoplasmosis. Are cats really the source?". Aust Fam Physician. 30 (8): 743–7. PMID 11681144. Cite error: The named reference "Torda_2001" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The New York Times 2006/06/20

- ^ a b c Montoya J, Liesenfeld O (2004). "Toxoplasmosis". Lancet. 363 (9425): 1965–76. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. PMID 15194258.

- ^ Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Sanders-Lewis K, Wilson M (2007). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States, 1999–2004, decline from the prior decade". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 77 (3): 405–10. PMID 17827351.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Beware of the cat: Britain's hidden toxoplasma problem".[1]

- ^ How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy

- ^ "Toxoplasma gondii immunoglobulin G antibodies and nonfatal suicidal self-directed violence".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[2] - ^ Mortensen, Preben Bo (2012). "Toxoplasma gondii Infection and Self-directed Violence in Mothers". Archives of General Psychiatry: 1. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.668.[3]

- ^ Ling, VJ; Lester, D; Mortensen, PB; Langenberg, PW; Postolache, TT (2011). "Toxoplasma gondii Seropositivity and Suicide rates in Women". The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 199 (7): 440–444. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318221416e. PMC 3128543. PMID 21716055.[4]

- ^ Paul M (1 July 1999). "Immunoglobulin G Avidity in Diagnosis of Toxoplasmic Lymphadenopathy and Ocular Toxoplasmosis". Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6 (4): 514–8. PMC 95718. PMID 10391853.

- ^ "Lymphadenopathy". Btinternet.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2010-07-28.[dead link]

- ^ Randall Parker: Humans Get Personality Altering Infections From Cats. September 30, 2003

- ^ Klaus, Sidney N.; Shoshana Frankenburg, and A. Damian Dhar (2003). "Chapter 235: Leishmaniasis and Other Protozoan Infections". In Freedberg; et al. (eds.). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138067-1.

- ^ Kar N, Misra B.Toxoplasma seropositivity and depression: a case report. BMC Psychiatry. 2004 Feb 5;4:1.doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-1 PMID 15018628

- ^ Henriquez SA, Brett R, Alexander J, Pratt J, Roberts CW.Neuropsychiatric disease and Toxoplasma gondii infection. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(2):122-33. Epub 2009 Feb 11.doi:10.1159/000180267 PMID 19212132

- ^ a b 3 Schizophrenia Cite error: The named reference "newscientist.com" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "'Cat Lady' Conundrum - Rebecca Skloot". The New York Times. 2007-12-09.

- ^ Jung, BK (2012 March 21). Heimesaat, Markus M (ed.). "Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the Brain Inhibits Neuronal Degeneration and Learning and Memory Impairments in a Murine Model of Alzheimer's Disease". PLoS ONE 7(3): e33312. 7 (3): e33312. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033312.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ LIn, WY (2012 Jul-Sep). "Association analysis of dopaminergic gene variants (Comt, Drd4 And Dat1) with Alzheimer's disease". J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 26 (3): 401–10. PMID 23034259.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Santtila, Pekka (5 FEB 2010). "The Dopamine Transporter Gene (DAT1) Polymorphism is Associated with Premature Ejaculation". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7 (4pt1): 1538–1546. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01696.x.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cornish, K M (5 April 2005). "Association of the dopamine transporter (DAT1) 10/10-repeat genotype with ADHD symptoms and response inhibition in a general population sample". Molecular Psychiatry. (2005) 10 (7): 686–698. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001641.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fitzmaurice, Arthur G. (2012 December 24). "Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibition as a pathogenic mechanism in Parkinson disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Science Of the United States of America. doi:10.1073/pnas.1220399110.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ho-Yen DO, Joss AW, Balfour AH, Smyth ET, Baird D, Chatterton JM (1992). "Use of the polymerase chain reaction to detect Toxoplasma gondii in human blood samples". J. Clin. Pathol. 45 (10): 910–3. doi:10.1136/jcp.45.10.910. PMC 495065. PMID 1430262.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Toxoplasmosis". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. 2004-11-22.

- ^ North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services

- ^ "Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection)". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. 2011-04-05.

- ^ Circular Normativa sobre Cuidados Pré-Concepcionais – Direcção-Geral de Saúde

- ^ a b c d e f Sukthana Y (2006). "Toxoplasmosis: beyond animals to humans". Trends Parasitol. 22 (3): 137–42. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2006.01.007. PMID 16446116.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [5][dead link]

- ^ a b M. De Paschale, C. Agrappi, P. Clerici, P. Mirri, M. T. Manco, S. Cavallari and E. F. Viganò: Seroprevalence and incidence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in the Legnano area of Italy. Clinical Microbiology and Infection Volume 14 Issue 2 (2007), Pages 186–189.

- ^ Ian Sample, science correspondent. "Pregnant women infected by cat parasite more likely to give birth to boys, say researchers | Science". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Webster, JP (2010 Jun). "Toxoplasma gondii-altered host behaviour: clues as to mechanism of action". Folia parasitologica. 57 (2): 95–104. PMID 20608471.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Webster, JP (2007 May). "The effect of Toxoplasma gondii on animal behavior: playing cat and mouse". Schizophrenia bulletin. 33 (3): 752–6. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl073. PMC 2526137. PMID 17218613.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Berdoy, M (2000 Aug 7). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proceedings. Biological sciences / the Royal Society. 267 (1452): 1591–4. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. PMC 1690701. PMID 11007336.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Vyas, A; Kim; Giacomini; Boothroyd; Sapolsky (2007 Apr 10). "Behavioral changes induced by Toxoplasma infection of rodents are highly specific to aversion of cat odors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (15): 6442–7. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6442V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608310104. PMC 1851063. PMID 17404235.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Xiao, J (2012 Mar 29). "Sex-specific changes in gene expression and behavior induced by chronic Toxoplasma infection in mice". Neuroscience. 206: 39–48. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.051. PMID 22240252.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lamberton, PH (2008 Sep). "Specificity of theToxoplasma gondii-altered behaviour to definitive versus non-definitive host predation risk". Parasitology. 135 (10): 1143–50. doi:10.1017/S0031182008004666. PMID 18620624.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McConkey, GA (2013 Jan 1). "Toxoplasma gondii infection and behaviour – location, location, location?". The Journal of experimental biology. 216 (Pt 1): 113–9. doi:10.1242/jeb.074153. PMC 3515035. PMID 23225873.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Afonso, C; Paixão; Costa (2012). Hakimi, Mohamed-Ali (ed.). "Chronic Toxoplasma infection modifies the structure and the risk of host behavior". PloS one. 7 (3): e32489. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732489A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032489. PMC 3303785. PMID 22431975.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gonzalez, LE (2007 Feb 12). "Toxoplasma gondii infection lower anxiety as measured in the plus-maze and social interaction tests in rats A behavioral analysis". Behavioural brain research. 177 (1): 70–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.012. PMID 17169442.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ [dead link]"Toxoplasmosis – treatment key research". NAM & aidsmap. 2005-11-02.

- ^

Djurković-Djaković O, Milenković V, Nikolić A, Bobić B, Grujić J (2002). "Efficacy of atovaquone combined with clindamycin against murine infection with a cystogenic (Me49) strain of Toxoplasma gondii" (PDF). J Antimicrob Chemother. 50 (6): 981–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dkf251. PMID 12461021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Pappas, G (2009 Oct). "Toxoplasmosis snapshots: global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis". International journal for parasitology. 39 (12): 1385–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.04.003. PMID 19433092.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Jones, JL (2007 Sep). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States, 1999 2004, decline from the prior decade". The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 77 (3): 405–10. PMID 17827351.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "CDC: Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) – Pregnant Women". Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Dubey, JP (1998 May). "Toxoplasmosis of rats: a review, with considerations of their value as an animal model and their possible role in epidemiology". Veterinary parasitology. 77 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(97)00227-6. PMID 9652380.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory: Laboratory Tests For The Diagnosis Of Toxoplasmosis

- ^ Arthur Ashe, Tennis Star, is Dead at 49 New York Times (02/08/93)

- ^ Merritt Butrick, A Biography Angelfire.com, accessdate Mar 18, 2011

- ^ "Pregnancy superfoods revealed". BBC News. January 10, 2001. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "Olympics bid Coes finest race". The Times. London. June 26, 2005. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "PERSONAL HEALTH". New York Times. 27 October 1982.

- ^ "Topic 33. Coccidia and Cryptosporidium spp". Biology 625: Animal Parasitology. Kent State Parasitology Lab. October 24, 2005. Retrieved 2006-10-14. Includes a list of famous victims.

- ^ "How Your Cat is Making You Crazy". The Atlantic. March 2012.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ J.P Dubey (2010)

- ^ a b c d Tenter, AM (2000 Nov). "Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans". International journal for parasitology. 30 (12–13): 1217–58. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7. PMC 3109627. PMID 11113252.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Dubey, JP (2008 Sep). "Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and animals in the United States". International journal for parasitology. 38 (11): 1257–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.03.007. PMID 18508057.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Jones, JL (2012 Sep). "Foodborne toxoplasmosis". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 55 (6): 845–51. doi:10.1093/cid/cis508. PMID 22618566.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 145-151

- ^ Dubey, JP (2008 Jul). "High prevalence and abundant atypical genotypes of Toxoplasma gondii isolated from lambs destined for human consumption in the USA". International journal for parasitology. 38 (8–9): 999–1006. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.11.012. PMID 18191859.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dubey, JP (2011 Jul). "High prevalence and genotypes ofToxoplasma gondii isolated from goats, from a retail meat store, destined for human consumption in the USA". International journal for parasitology. 41 (8): 827–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.006. PMID 21515278.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dubey, JP (2010 Feb). "Toxoplasma gondii infections in chickens (Gallus domesticus): prevalence, clinical disease, diagnosis and public health significance". Zoonoses and public health. 57 (1): 60–73. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01274.x. PMID 19744305.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 723

- ^ a b c d Elmore, SA (2010 Apr). "Toxoplasma gondii: epidemiology, feline clinical aspects, and prevention". Trends in parasitology. 26 (4): 190–6. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.009. PMID 20202907.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jokelainen, P (2012 Nov). "Feline toxoplasmosis in Finland: cross-sectional epidemiological study and case series study". Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation : official publication of the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Inc. 24 (6): 1115–24. doi:10.1177/1040638712461787. PMID 23012380.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Al-Kappany, YM (2010 Dec). "High prevalence of toxoplasmosis in cats from Egypt: isolation of viable Toxoplasma gondii, tissue distribution, and isolate designation". The Journal of parasitology. 96 (6): 1115–8. doi:10.1645/GE-2554.1. PMID 21158619.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 95

- ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 46

- ^ Conrad P, Miller M, Kreuder C, James E, Mazet J, Dabritz H, Jessup D, Gulland F, Grigg M (2005). "Transmission of Toxoplasma: clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels of Toxoplasma gondii flow into the marine environment". Int J Parasitol. 35 (11–12): 1155–68. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.002. PMID 16157341.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 17:30–22:00 "Treating Disease in the Developing World". Talk of the Nation Science Friday. National Public Radio. December 16, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Parasite in cats killing sea otters". NOAA magazine. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 21 January 2003. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- Parts of this article are taken from the public domain CDC factsheet: Toxoplasmosis

Bibliography

- Louis M Weiss; Kami Kim (28 April 2011). Toxoplasma Gondii: The Model Apicomplexan. Perspectives and Methods. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-047501-1. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- J. P. Dubey (15 April 2010). Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-9237-0. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

External links

- Toxoplasmosis at The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- Toxoplasmosis at Health Protection Agency (HPA), United Kingdom

- Pictures of Toxoplasmosis Medical Image Database

- Video-Interview with Professor Robert Sapolsky on Toxoplasmosis and its affect on human behavior. (24:27 min)