Hyperinflation: Difference between revisions

m which -> that |

|||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

None of these actions address the root causes of inflation, and in fact, if discovered, tend to further undermine trust in the currency, causing further increases in inflation. |

None of these actions address the root causes of inflation, and in fact, if discovered, tend to further undermine trust in the currency, causing further increases in inflation. |

||

== Excess Money Supply: good intentions causing the Great Robbery == |

|||

Money can only maintain its buying power when an increase in the money supply is matched by an equavalent increase of the supply of real goods and services. Central Banks often set interest rates at artificially low levels supposedly to stimulate growth. These low interest rates cause demand for loans to increase excessively and the money supply to expand at a faster rate than the real economy. This results in fast growing amounts of money chasing slowly growing quantities of goods causing the price levels to rise. |

|||

Inflationary money such as bankers create from thin air obviously does not increase the real buying power of a country, as their increase of the money supply is not accompanied by an increase of real goods or services. The nominal buying power such money provides to borowers is merely diluted buying power, deluted from the real buying power of someone else. It is indeed buying power stealthy robbed from people having earned theirs through hard labour or in exchange for the delivery of real goods and services. Obviously the stealthly devaluation of peoples' labour and savings progressively discourages producers of real wealth. Eventually they tend to reduce their productive contribution, resulting in slowdown of real growth; just the opposit easy money was supposed to do. So contrary to popular belief excessive money supply can never cause real growth, but merely creates a nominal illusion of progress. |

|||

In the end real wealth can only be increased through increasing the availability over real goods and services. And the only way to increase production is by working more or by producing more efficiently. And efficiency can only be increased to any substantial extend through investment in better machines, better techniques or improved infrastructure. Any policy aiming real growth must therefor promote investment and saving, and certainly should never stimulate consumption. Easy money does exactly the opposite: it de-motivates saving, investment and productive contribution, in the long run all slowing down real growth exactly the opposit it was set up to do. |

|||

Artificially low intests merely provide artificial borrowing margins creating an illusion of wealth. This easy access to loans is incouraging borrowers to engage in insustainable debt. It temporarily produces an artificial excess of demand over supply, temporarily making everything saleable; from the most obsolete consumer goods to industrial projects whose life-cycle has since long gone by. Artificially low interest rates consequently also tend to immobilise resources in outdated and low-return projects ultimately slowing down productivity gains. |

|||

The most devestating effect of easy-money however is that by penalising saving, it stimulates over-consumption, and slows down capital formation; ultimately the indispensable means of all technological progress. |

|||

* see: [http://workforall.net/the_path_to_sustainable_growth.html '''The Path to sustainable Growth. '''] - Lessons from 20 years Growth Differentials in Europe - 2006 - ''Free Institure for Economic Research.'' |

|||

==Hyperinflation around the world== |

==Hyperinflation around the world== |

||

Revision as of 13:15, 29 September 2006

This article or section appears to contradict itself. |

- Certain figures in this article use scientific notation for readability.

In economics, hyperinflation is inflation that is "out of control", a condition in which prices increase rapidly as a currency loses its value. No precise definition of hyperinflation is universally accepted. One simple definition requires a monthly inflation rate of 50% or more. In informal usage the term is often applied to much lower rates. The definition used by most economists is "an inflationary cycle without any tendency toward equilibrium." A vicious circle is created in which more and more inflation is created with each iteration of the cycle. Although there is a great deal of debate about the root causes of hyperinflation, it becomes visible when there is an unchecked increase in the money supply or drastic debasement of coinage, and is often associated with wars (or their aftermath), economic depressions, and political or social upheavals.

Characteristics

In 1956, Phillip Cagan wrote "Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation", generally regarded as the first serious study of hyperinflation and its effects. In it he defined hyperinflation as a monthly inflation rate of at least 50% (prices doubling every 51 days).

International Accounting Standard 29 describes four signs that an economy may be in hyperinflation:

- The general population prefers to keep its wealth in non-monetary assets or in a relatively stable foreign currency. Amounts of local currency held are immediately invested to maintain purchasing power.

- The general population regards monetary amounts not in terms of the local currency but in terms of a relatively stable foreign currency. Prices may be quoted in that currency. According to a Newsweek magazine article, in Turkey in the late 1990s, people used the United States dollar as a reference although that country suffered only chronic inflation.

- Sales and purchases on credit take place at prices that compensate for the expected loss of purchasing power during the credit period, even if the period is short.

- Interest rates, wages and prices are linked to a price index and the cumulative inflation rate over three years approaches, or exceeds, 100%.

Rates of inflation of several hundred percent per month are often seen. Extreme examples include Germany in the early 1920s when the rate of inflation hit 3.25 × 106 percent per month (prices double every 49 hours) and Greece during its occupation by German troops (1941-1944) with 8.55 × 109 percent per month (prices double every 28 hours). The most severe known incident of inflation was in Hungary after the end of World War II at 4.19 × 1016 percent per month (prices double every 15 hours). More recently, Yugoslavia suffered 5 × 1015 percent inflation per month (prices double every 16 hours) between 1 October 1993 and 24 January 1994. Other more moderate examples include other Eastern European countries such as Ukraine in the period of economic transition in the early 1990s, in Latin American countries such as Bolivia and Peru in 1985 and 1988-1990, in Mexico from 1982 to 1988, in Argentina in 1989, in Brazil in the early 1990s, and in the African nation of Zimbabwe in 2006. Hyperinflation in Mexico eventually forced prices so high that in 1993 Carlos Salinas de Gortari had to replace the peso ($) with the nuevo peso (N$). The parity was N$1 for $1000 – in short, he stripped three zeroes from the peso.

Root causes of hyperinflation

Hyperinflation is generally associated with paper money because the means to increasing the money supply with paper money is the simplest: add more zeroes to the plates and print, or even stamp old notes with new numbers. It also is the most dramatic. There have been numerous episodes of hyperinflation, followed by a return to "hard money". Older economies would revert to hard currency and barter when the circulating medium became excessively devalued, generally following a "run" on the store of value.

Unlike inflation, which is widely considered to be normal in a healthy economy, hyperinflation is always regarded as destructive. It effectively wipes out the purchasing power of private and public savings, distorts the economy in favor of extreme consumption and hoarding of real assets, causes the monetary base whether specie or hard currency to flee the country, and makes the afflicted area anathema to investment. Hyperinflation is met with drastic remedies, whether by imposing a shock therapy of slashing government expenditures or by altering the currency basis. An example of the latter is placing the nation in question under a currency board as Bosnia-Herzegovina has now in 2005, which allows the central bank to print only as much money as it has in foreign reserves. Another example is dollarization as Ecuador officially initiated in September 2000 in response to a massive 75% loss of value of the Sucre currency in early January 2000. Dollarization is the use of a foreign currency (not necessarily the U.S. dollar) as a national unit of currency.

The aftermath of hyperinflation is equally complex. As hyperinflation has always been a traumatic experience for the area which suffers it, the next policy regime almost always enacts policies to prevent its recurrence. Often this means making the central bank very aggressive about maintaining price stability as is the case with the German Bundesbank, or moving to some hard basis of currency such as a currency board. Many governments have enacted extremely stiff wage and price controls in the wake of hyperinflation, which is, in effect, a form of forced savings: goods become unavailable, and hence people hoard cash, as was the case in the People's Republic of China under "Great Leap Forward" and "Cultural Revolution".

For a variety of reasons, governments have occasionally resorted to printing money to meet their expenses. During hyperinflation, the monetary authority can't even do that as it becomes a net loss. Those holding government debt, directly or indirectly, have less buying power. Theories of hyperinflation generally look for a relationship between seignorage and the inflation tax. In both Cagan's model and the neo-classical models, a crucial point is when the increase in money supply or the drop in basic money stock makes it impossible for a government to improve its financial position. That is, when fiat money is printed government obligations that are not denominated in money increase in cost by more than the value of the money created.

From this, it might be wondered why any state would engage in actions that cause or continue hyperinflation. One reason is that often the alternative to hyperinflation is depression. In late 2001, the Argentine peso collapsed in value. Rather than printing sufficient cash for the public to carry, which they feared would start a run on the banks, the government took the peso off its dollar peg. Many international economists predicted that they would have to get a new loan from the IMF and impose shock therapy in order to avoid hyperinflation. Currency controls were imposed, tariffs were instituted, and the economy was allowed to fall into a severe recession during which unemployment hit 25%, homelessness and crime spiraled upwards, and the poverty rate peaked at over 50%.

The root cause is a matter of more dispute. In both classical economics and monetarism, it is always the result of the monetary authority irresponsibly borrowing money to pay all its expenses. These models focus on the unrestrained seignorage of the monetary authority, and the gains from the inflation tax. In Neoliberalism, hyperinflation is considered to be the result of a crisis of confidence. The monetary base of the country flees, producing widespread fear that individuals will not be able to convert local currency to some more transportable form, such as gold or an internationally recognized hard currency. This is a quantity theory of hyper-inflation.

In neo-classical economic theory, hyperinflation is rooted in a deterioration of the monetary base, that is the confidence that there is a store of value which the currency will be able to command later. In this model, the perceived risk of holding currency rises dramatically, and sellers demand increasingly high premiums to accept the currency. This in turn leads to a greater fear that the currency will collapse, causing even higher premiums. One example of this is during periods of warfare, civil war, or intense internal conflict of other kinds: governments need to do whatever is necessary to continue fighting, since the alternative is defeat. Expenses cannot be cut significantly since the main outlay is armaments. Further, a civil war may make it difficult to raise taxes or to collect existing taxes. While in peacetime the deficit is financed by selling bonds, during a war it is typically difficult and expensive to borrow, especially if the war is going poorly for the government in question. The banking authorities, whether central or not, "monetize" the deficit, printing money to pay for the government's efforts to survive. The hyperinflation under the Chinese Nationalists from 1939-1945 is a classic example of a government printing money to pay civil war costs. By the end, currency was flown in over the Himalaya, and then old currency was flown out to be destroyed.

Hyperinflation is regarded as a complex phenonomenon and one explanation may not be applicable to all cases. However, in both of these models, whether loss of confidence comes first, or central bank sienurage, the other phase is ignited. In the case of rapid expansion of the money supply, prices rise rapidly in response to the increased demand beyond the ability of the economy to supply it, and in the case of loss of confidence, the monetary authority responds to the risk premiums it has to pay by "running the printing presses".

In the United States, hyperinflation was seen during the Revolutionary War and during the Civil War, especially on the Confederate side. Many other cases of extreme social conflict encouraging hyperinflation can be seen, as in Germany after World War I, Hungary at the end of World War II and in Yugoslavia in late 1980s just before break up of the country.

Less commonly, hyperinflation may occur when there is debasement of the coinage — wherein coins are consistently shaved of some of their silver and gold, increasing the circulating medium and reducing the value of the currency. The "shaved" specie is then often restruck into coins with lower weight of gold or silver. Historical examples include Ancient Rome and China during the Song Dynasty. When "token" coins begin circulating, it is possible for the minting authority to engage in fiat creation of currency.

Hyperinflation can also occur in the absence of a central bank. One case is when there is "free banking" but banks are allowed suspend convertibility, often in violation of explicit or implicit promises and contracts. These episodes often cause a panicked run on banks and a collapse in the money supply, leading to a depression and deflation.

The 1920s German inflation

The hyperinflation episode in the Weimar Republic in the 1920s was not the first hyperinflation, nor was it the only one in early 1920s Europe. However, as the most prominent case following the emergence of economics as a science, it drew interest in a way that previous instances had not. Many of the surreal economic behaviors now associated with hyperinflation were first documented systematically in Germany: order-of-magnitude increases in prices and interest rates, redenomination of the currency, consumer flight from cash to hard assets, and the rapid expansion of industries that produced those assets.

It is sometimes argued that Germany had to inflate its currency to pay the war reparations required under the Treaty of Versailles, but this is only part of the story. Reparations accounted for about one third of the German deficit from 1920 to 1923 (Costantino Bresciani-Turroni, The Economics of Inflation. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1937. p. 93). Nonetheless, the government found reparations a convenient scapegoat. Other scapegoats included bankers and speculators (particularly foreign or Jewish). The inflation reached its peak by November 1923, but ended when a new currency (the Rentenmark) was introduced. The government stated this new currency had a fixed value, and this was accepted.

Hyperinflation did not directly bring about the Nazi takeover of Germany; the inflation ended with the introduction of the Rentenmark and the Weimar Republic continued for a decade afterward. The inflation did, however, raise doubts about the competence of liberal institutions, especially amongst a middle class who had held cash savings and bonds. It also produced resentment of Germany's bankers and speculators, many of them Jewish, whom the government and press blamed for the inflation.

Models of hyperinflation

Since hyperinflation is visible as a monetary effect, models of hyperinflation center on the demand for money. Economists see both a rapid increase in the money supply and an increase in the velocity of money. Either one or both of these encourage inflation and hyperinflation. A dramatic increase in the velocity of money as the cause of hyperinflation is central to the "crisis of confidence" model of hyperinflation, where the risk premium that sellers demand for the paper currency over the nominal value grows rapidly. The second theory is that there is first a radical increase in the amount of circulating medium, which can be called the "monetary model" of hyperinflation. In either model, the second effect then follows from the first — either too little confidence forcing an increase in the money supply, or too much money destroying confidence.

In the confidence model, some event, or series of events, such as defeats in battle, or a run on stocks of the specie which back a currency, removes the belief that the authority issuing the money will remain solvent — whether a bank or a government. Because people do not want to hold notes which may become valueless, they want to spend them in preference to holding notes which will lose value. Sellers, realizing that there is a higher risk for the currency, demand a greater and greater premium over the original value. Under this model, the method of ending hyperinflation is to change the backing of the currency — often by issuing a completely new one. War is one commonly cited cause of crisis of confidence, particularly losing in a war, as occurred during Napoleonic Vienna, and capital flight, sometimes because of "contagion" is another. In this view, the increase in the circulating medium is the result of the government attempting to buy time without coming to terms with the root cause of the lack of confidence itself.

In the monetary model, hyperinflation is a positive feedback cycle of rapid monetary expansion. It has the same cause as all other inflation: money-issuing bodies, central or otherwise, produce currency to pay spiralling costs, often from lax fiscal policy, or the mounting costs of warfare. When businesspeople perceive that the issuer is committed to a policy of rapid currency expansion, they mark up prices to cover the expected decay in the currency's value. The issuer must then accelerate its expansion to cover these prices, which pushes the currency value down even faster than before. According to this model the issuer cannot "win" and the only solution is to abruptly stop expanding the currency. Unfortunately, the end of expansion can cause a severe financial shock to those using the currency as expectations are suddenly adjusted. This policy, combined with reductions of pensions, wages, and government outlays, formed part of the Washington consensus of the 1990s.

Whatever the cause, hyperinflation involves both the supply and velocity of money. Which comes first is a matter of debate, and there may be no universal story that applies to all cases. But once the hyperinflation is established, the pattern of increasing the money stock, by which ever agencies are allowed to do so, is universal. Because this practice increases the supply of currency without any matching increase in demand for it, the price of the currency, that is the exchange rate, naturally falls relative to other currencies. Inflation becomes hyperinflation when the increase in money supply turns specific areas of pricing power into a general frenzy of spending quickly before money becomes worthless. The purchasing power of the currency drops so rapidly that holding cash for even a day is an unacceptable loss of purchasing power. As a result, no one holds currency, which increases the velocity of money, and worsens the crisis.

That is, rapidly rising prices undermine money's role as a store of value, so that people try to spend it on real goods or services as quickly as possible. Thus, the monetary model predicts that the velocity of money will rise endogenously as a result of the excessive increase in the money supply. At the point where ordinary purchases are affected by inflation pressures, hyperinflation is out of control, in the sense that ordinary policy mechanisms, such as increasing reserve requirements, raising interest rates or cutting government spending will all be responded to by shifting away from the rapidly dwindling currency and towards other means of exchange.

During a period of hyperinflation, bank runs, loans for 24 hour periods, switching to alternate currencies, the return to use of gold or silver or even barter becomes common. Many of the people who hoard gold today expect hyperinflation, and are hedging against it by holding specie. There is, also, extensive capital flight or flight to a "hard" currency such as the U.S. dollar. These are sometimes met with capital controls, an idea which has swung from standard, to anathema, and back into semi-respectability. All of this constitutes an economy which is operating in an "abnormal" way, which may lead to decreases in real production. If so, that intensifies the hyperinflation, since it means that the amount of goods in "too much money chasing too few goods" formulation is also reduced. This is also part of the vicious circle of hyperinflation.

Once the vicious circle of hyperinflation has been ignited, dramatic policy means are almost always required, simply raising interest rates is insufficient. Bolivia, for example, underwent a period of hyperinflation in 1985, where prices increased 12,000% in the space of less than a year. The government raised the price of gasoline, which it had been selling at a huge loss to quiet popular discontent, and the hyperinflation came to a halt almost immediately, since it was able to bring in hard currency by selling its oil abroad. The crisis of confidence ended, and people returned deposits to banks. The German hyperinflation of the 1920s was ended by producing a currency based on assets loaned against by banks, called the Rentenmark. Hyperinflation often ends when a civil conflict ends with one side winning. Though sometimes used, wage and price controls to control or prevent inflation, no episode of hyperinflation has been ended by the use of price controls alone, though they have sometimes been part of the mix of policies used to halt hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation and the currency

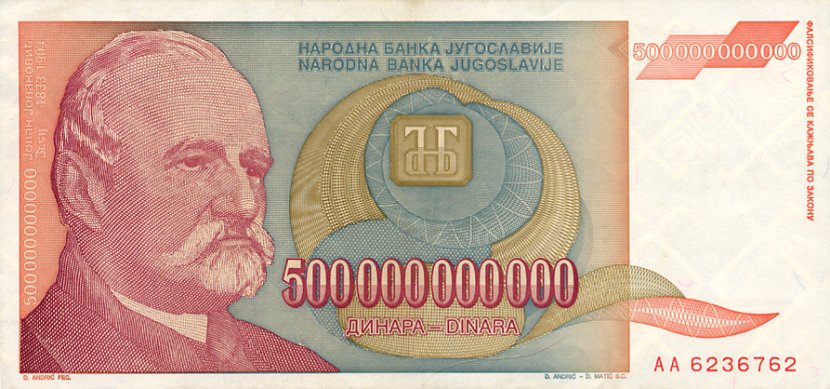

As noted, in countries experiencing hyperinflation, the central bank often prints money in larger and larger denominations as the smaller denomination notes become worthless. This can result in the production of some interesting banknotes, including those denominated in amounts of 1,000,000,000 or more.

- By late 1923, the Weimar Republic of Germany was issuing fifty-million-mark banknotes and postage stamps with a face value of fifty billion mark. The highest value banknote issued by the Weimar government's Reichsbank had a face value of 100 billion mark (100,000,000,000,000) {100 Trillion US/UK}. [1]. One of the firms printing these notes submitted an invoice for the work to the Reichsbank for 32,776,899,763,734,490,417.05 (3.28×1019, or 33 quintillion) mark.

- The largest denomination banknote ever officially issued for circulation was in 1946 by the Hungarian National Bank for the amount of 100 quintillion pengő (100,000,000,000,000,000,000, or 1020). image (There was even a banknote worth 10 times more, i.e. 1021 pengő, printed, but not issued image.) The Post-WWII hyperinflation of Hungary holds the record for the most extreme monthly inflation rate ever — 41,900,000,000,000,000% (4.19 16%) for July, 1946, amounting to prices doubling every fifteen hours.

One way to avoid the use of large numbers is by declaring a new unit of currency (so, instead of 10,000,000,000 Dollars, a bank might set 1 new dollar = 1,000,000,000 old dollars, so the new note would read "10 new dollars".) An example of this would be Turkey's revaluation of the Lira on January 1st, 2005, when the old Turkish Lira (TRL) was converted to the new Turkish Lira (YTL) at a rate of 1,000,000 old to 1 new Turkish Lira. While this does not lessen actual value of a currency, it is called revaluation and also happens over time in countries with standard inflation levels. During hyperinflation, currency inflation happens so quickly that bills reach large numbers before revaluation.

Some banknotes were stamped to indicate changes of denomination. This is because it would take too long to print new notes. By time the new notes would be printed, they would be obsolete (that is, they would be of too low a denomination to be useful).

Metallic coins were rapid casualties of hyperinflation, as the scrap value of metal enormously exceeded the face value. Massive amounts of coinage were melted down, usually illictly, and exported for hard currency.

Governments will often try to disguise the true rate of inflation through a variety of techniques. These can include the following:

- Outright lying as to official statistics such as money supply, inflation or reserves.

- Suppression of publication of money supply statistics, or inflation indices.

- Price and wage controls.

- Forced savings schemes, designed to suck up excess liquidity. These savings schemes may be described as pensions schemes, emergency funds, war funds, or similar.

- Adjusting the components of the Consumer Price Index, to remove those items whose prices are rising the fastest.

None of these actions address the root causes of inflation, and in fact, if discovered, tend to further undermine trust in the currency, causing further increases in inflation.

Excess Money Supply: good intentions causing the Great Robbery

Money can only maintain its buying power when an increase in the money supply is matched by an equavalent increase of the supply of real goods and services. Central Banks often set interest rates at artificially low levels supposedly to stimulate growth. These low interest rates cause demand for loans to increase excessively and the money supply to expand at a faster rate than the real economy. This results in fast growing amounts of money chasing slowly growing quantities of goods causing the price levels to rise.

Inflationary money such as bankers create from thin air obviously does not increase the real buying power of a country, as their increase of the money supply is not accompanied by an increase of real goods or services. The nominal buying power such money provides to borowers is merely diluted buying power, deluted from the real buying power of someone else. It is indeed buying power stealthy robbed from people having earned theirs through hard labour or in exchange for the delivery of real goods and services. Obviously the stealthly devaluation of peoples' labour and savings progressively discourages producers of real wealth. Eventually they tend to reduce their productive contribution, resulting in slowdown of real growth; just the opposit easy money was supposed to do. So contrary to popular belief excessive money supply can never cause real growth, but merely creates a nominal illusion of progress.

In the end real wealth can only be increased through increasing the availability over real goods and services. And the only way to increase production is by working more or by producing more efficiently. And efficiency can only be increased to any substantial extend through investment in better machines, better techniques or improved infrastructure. Any policy aiming real growth must therefor promote investment and saving, and certainly should never stimulate consumption. Easy money does exactly the opposite: it de-motivates saving, investment and productive contribution, in the long run all slowing down real growth exactly the opposit it was set up to do.

Artificially low intests merely provide artificial borrowing margins creating an illusion of wealth. This easy access to loans is incouraging borrowers to engage in insustainable debt. It temporarily produces an artificial excess of demand over supply, temporarily making everything saleable; from the most obsolete consumer goods to industrial projects whose life-cycle has since long gone by. Artificially low interest rates consequently also tend to immobilise resources in outdated and low-return projects ultimately slowing down productivity gains.

The most devestating effect of easy-money however is that by penalising saving, it stimulates over-consumption, and slows down capital formation; ultimately the indispensable means of all technological progress.

- see: The Path to sustainable Growth. - Lessons from 20 years Growth Differentials in Europe - 2006 - Free Institure for Economic Research.

Hyperinflation around the world

- Angola

- Angola went through the worst inflation from 1991 to 1995. In early 1991, the highest denomination was 50,000 kwanzas. By 1994, it was 500,000 kwanzas. In the 1995 currency reform, 1 kwanza reajustado was exchanged for 1,000 kwanzas. The highest denomination in 1995 was 5,000,000 kwanzas reajustados. In the 1999 currency reform, 1 new kwanza was exchanged for 1,000,000 kwanzas reajustados. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 new kwanza = 1,000,000,000 pre 1991 kwanzas.

- Argentina

- Argentina went through steady inflation from 1975 to 1991. At the beginning of 1975, the highest denomination was 1,000 pesos. In late 1976, the highest denomination was 5,000 pesos. In early 1979, the highest denomination was 10,000 pesos. By the end of 1981, the highest denomination was 1,000,000 pesos. In the 1983 currency reform, 1 Peso Argentino was exchanged for 10,000 pesos. In the 1985 currency reform, 1 austral was exchanged for 1,000 pesos argentino. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new peso was exchanged for 10,000 australes. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 new peso = 100,000,000,000 pre-1983 pesos.

- Austria

- Between 1921 and 1922, inflation in Austria reached 134%.

- Belarus

- Belarus went through steady inflation from 1994 to 2002. In 1993, the highest denomination was 5,000 rublei. By 1999, it was 5,000,000 rublei. In the 2000 currency reform, the ruble was replaced by the new ruble at an exchange rate of 1 new ruble = 2,000 old rublei. The highest denomination in 2002 was 50,000 rublei, equal to 100,000,000 pre-2000 rublei.

- Bolivia

- Bolivia went through the worst inflation between 1984 and 1986. Before 1984, the highest denomination was 1,000 pesos bolivianos. By 1985, the highest denomination was 10 Million pesos bolivianos. In the 1987 currency reform, peso boliviano was replaced by boliviano which was pegged to U. S. dollar.

- Bosnia-Herzegovina

- Bosnia-Hezegovina went through its worst inflation in 1993. In 1992, the highest denomination was 1,000 dinara. By 1993, the highest denomination was 100,000,000 dinara. In the Republika Srpska, the highest denomination was 10,000 dinara in 1992 and 10,000,000,000 dinara in 1993. 50,000,000,000 dinara notes were also printed in 1993 but never issued.

- Brazil

- From 1986 to 1994, the base currency unit was shifted three times to adjust for inflation in the final years of the República Velha era. A 1960's cruzeiro was, in 1994, worth less than one trillionth of a US cent, after adjusting for multiple devaluations and note changes. A new currency called real was adopted in 1994, and hyperinflation was eventually brought under control.

- China

- China went through the worst inflation 1948-49. In 1947, the highest denomination was 50,000 yuan. By mid-1948, the highest denomination was 180,000,000 yuan. The 1948 currency reform replaced the yuan by the gold yuan at an exchange rate of 1 gold yuan = 3,000,000 yuan. In less than 1 year, the highest denomination was 10,000,000 gold yuan. The highest denomination by a regional bank was 6,000,000,000 yuan issued by Sinkiang Provincial Bank in 1949

- Free City of Danzig

- Danzig went through the worst inflation in 1923. In 1922, the highest denomination was 1,000 mark. By 1923, the highest denomination was 10,000,000,000 mark.

- Georgia

- Georgia went through the worst inflation in 1994. In 1993, the highest denomination was 100,000 laris. By 1994, the highest denomination was 1,000,000 laris. In the 1995 currency reform, 1 new lari was exchanged for 1,000,000 laris.

- Germany

- Germany went through the worst inflation in 1923-24. In 1922, the highest denomination was 50,000 mark. By 1923, the highest denomination was 100,000,000,000,000 mark. During the worst times, one U.S. dollar was equal to 80 billion mark.

- Greece

- Greece went through its worst inflation in 1944. In 1943, the highest denomination was 25,000 drachmai. By 1944, the highest denomination was 100,000,000,000,000 drachmai. In the 1944 currency reform, 1 new drachma was exchanged for 50,000,000,000 drachmai. Another currency reform in 1953 replaced the drachma at an exchange rate of 1 new drachma = 1,000 old drachma. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1953) drachma = 50,000,000,000,000 pre 1944 drachmai. The Greek inflation rate reached 8.5 billion percent.

- Hungary

- Hungary went through the worst inflation in modern history in 1945-46. Before 1945, the highest denomination was 1,000 pengő. By the end of 1945, it was 10,000,000 pengő. The highest denomination in mid-1946 was 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 pengő. Banknotes The rate of inflation was 4.19 quintillion percent. A special currency the adópengő - or tax pengő - was created for tax and postal payments [2]. The value of the adópengő was adjusted each day, by radio announcement. On January 1, 1946 one adópengő equaled one pengő. By late July, one adópengő equaled 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or 2×1021pengő.

- One source [3] states that this hyperinflation was purposely started by trained Russian Marxists in order to destroy the Hungarian middle and upper classes. The 1946 currency reform changed the currency to forint. Previously, between 1922 and 1924 inflation in Hungary reached 98%.

- Israel

- Inflation accelerated in the 1970s, rising steadily from 13% in 1971 to 111% in 1979.From 133% in 1980, it leaped to 191% in 1983 and then to 445% in 1984, threatening to become a four-digit figure within a year or two. In 1985 Israel froze all prices by law. In 1985, inflation fell to 185% (less than half the rate in 1984). Within a few months, the authorities began to lift the price freeze on some items; in other cases it took almost a year. In 1986, inflation was down to just 19%.

- Krajina

- Krajina went through the worst inflation in 1993. In 1992, the highest denomination was 50,000 dinara. By 1993, the highest denomination was 50,000,000,000 dinara. Note that this unrecognized country was reincorporated into Croatia in 1998.

- Madagascar

- The Malagasy franc had a turbulent time in 2004, losing nearly half its value and sparking rampant inflation. On 1st January 2005 the Malagasy ariary replaced the previous currency at a rate of 0.2 ariary for one Malagasy franc. In May 2005 there were riots over rising inflation, although falling prices have since calmed the situation.

- Nicaragua

- Nicaragua went through the worst inflation from 1987 to 1990. Before 1987, the highest denomination was 1,000 cordobas. By 1987, it was 500,000 cordobas. In the 1988 currency reform, 1 new cordoba was exchanged for 1,000 old cordobas. The highest denomination in 1990 was 100,000,000 new cordobas. In the mid-1990 currency reform, 1 gold cordoba was exchanged for 5,000,000 new cordobas. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 gold cordoba = 5,000,000,000 pre 1988 cordobas.

- Peru

- Peru went through the worst inflation from 1984 to 1990. The highest denomination in 1984 was 50,000 soles de oro. By 1985, it was 500,000 soles de oro. In the 1985 currency reform, 1 inti was exchanged for 1000 soles de oro. In 1986, the highest denomination was 1,000 intis. It was 20,000,000 intis by 1991. In the 1991 currency reform, 1 nuevo sol was exchanged for 1,000,000 intis. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 nuevo sol = 1,000,000,000 pre 1985 soles de oro.

- Poland

- Poland went through the worst inflation between 1990 and 1993. The highest denomination in 1989 was 200,000 zlotych. It was 1,000,000 zlotych in 1991 and 2,000,000 zlotych in 1992. In the 1994 currency reform, 1 new zloty was exchanged for 10,000 old zlotych. Previously between 1922 and 1924, Polish inflation reached 275%.

- Romania

- Romania is still working through steady inflation. The highest denomination in 1998 was 100,000 lei. By 2000 it was 500,000 lei. In early 2005 it was 1,000,000 lei. In July 2005 the leu was replaced by the new leu at 10,000 old lei = 1 new leu. Inflation in 2005 was 9%. In 2006 the highest denomination is 500 lei (= 5,000,000 old lei).

- Russia

- Between 1921 and 1922, during the civil war, inflation in Russia reached 213%.

- In 1992, the first year of post-Soviet economic reform, inflation was 2,520%, the major cause being the decontrol of most prices in January. In 1993 the annual rate was 840%, and in 1994, 224%. The ruble devalued from about 100 r/$ in 1991 to about 30,000 r/$ in 1999.

- Taiwan

- Severe inflation existed in the late 1940s due to factors such as corruption and the 228 Incident. Increasingly higher denominations were issued on the island, up to one million yuan. Inflation was eventually controlled after the new Taiwan dollar was issued in 1949 at a ratio of 40,000-to-1 against the old Taiwan nationalist yuan.

- Turkey

- Throughout the 1990s Turkey dealt with severe inflation rates that finally crippled the economy into a recession in 2001. The highest denomination in 1995 was 1,000,000 lira. By 2000 it was 20,000,000 lira. Recently Turkey has achieved single digit inflation for the first time in decades, and in the 2005 currency reform, introduced the New Turkish Lira; 1 was exchanged for 1,000,000 old lira.

- Ukraine

- Ukraine went through the worst inflation between 1993 and 1995. Before 1993, the highest denomination was 1,000 karbovantsiv. By 1995, it was 1,000,000 karbovantsiv. In 1992, it introduced the Ukrainian karbovanets, which was exchanged from then-defunct Soviet ruble at a rate of 1 UAK = 1 SUR. In 1996, during the transition to the Hryvnya and the subsequent phase out of the karbovanets, the exchange rate was 100,000 UAK = 1 UAH. This translates to a hyperinflation rate of approximately 1400% per month.

- United States

- During The Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress authorized the printing of paper currency called continental currency. The easily counterfeited notes depreciated rapidly, giving rise to the expression "not worth a continental."

- Between January 1861 and April 1865, the Lerner Commodity Price Index of leading cities in the eastern Confederacy increased from 100 to over 9000.

- Yap

- The island of Yap in the Pacific ocean used varying sized stones as money, of which the largest weighing several tons were the most valuable. The stones had been brought by sea from the Island of Palau 210km away. The journey was very perilous given the length of the voyage and the rough seas between the islands of Palau and Yap. Many of the stones were lost at sea. The risk associated with procurement of the "money stones" initially made them highly valuable. The Yapese valued them because large stones were quite difficult to steal and were in relatively short supply. However, in 1874, an enterprising Irishman called David O’Keefe hit upon the idea of employing the Yapese to import more "money" in the form of shiploads of large stones, also from Palau. O'Keefe then traded these stones with the Yapese for other commodities such as sea cucumbers and copra. Over time, the Yapese brought thousands of new stones to the island, debasing the value of the old ones. Today they are almost worthless, except as a tourist curiosity.

- Yugoslavia

- Yugoslavia went through a period of hyperinflation and subsequent currency reforms from 1989 to 1994. The highest denomination in 1988 was 50,000 dinars. By 1989 it was 2,000,000 dinars. In the 1990 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10,000 old dinars. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10 old dinars. The highest denomination in 1992 was 50,000 dinars. By 1993, it was 10,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1993 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000 old dinars. But before the year was over, the highest denomination was 500,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1994 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000,000 old dinars. In another currency reform a month later, 1 novi dinar was exchanged for 10~13 million dinars (1 novi dinar = 1 German mark at the time of exchange). The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 novi dinar = 1 27~1.3 27 pre 1990 dinars.

- Zaire

- Zaire went through a period of inflation between 1989 and 1996. In 1988, the highest denomination was 5,000 zaires. By 1992, it was 5,000,000 zaires. In the 1993 currency reform, 1 nouveau zaire was exchanged for 3,000,000 old zaires. The highest denomination in 1996 was 1,000,000 nouveaux zaires. In 1997, Zaire was renamed the Congo Democratic Republic and changed its currency to francs. 1 franc was exchanged for 100,000 nouveaux zaires. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 franc = 3 11 pre 1989 zaires.

| Zimbabwean inflation rates since Independence | |||||||||||

| Date | Rate | Date | Rate | Date | Rate | Date | Rate | Date | Rate | Date | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 7% | 1981 | 14% | 1982 | 15% | 1983 | 19% | 1984 | 10% | 1985 | 10% |

| 1986 | 15% | 1987 | 10% | 1988 | 8% | 1989 | 14% | 1990 | 17% | 1991 | 48% |

| 1992 | 40% | 1993 | 20% | 1994 | 25% | 1995 | 28% | 1996 | 16% | 1997 | 20% |

| 1998 | 48% | 1999 | 58% | 2000 | 56% | 2001 | 132% | 2002 | 139% | 2003 | 385% |

| 2004 | 624% | 2005 | 586% | 2006 | 1205% | ||||||

- At Independence, in 1980, the Zimbabwe dollar was worth about $1.50 US. Since then, rampant inflation and the collapse of the economy have severely devalued the currency, with many organisations using the US dollar instead.

- Early in the 21st century Zimbabwe started to experience hyperinflation. Inflation reached 624% in early 2004, then fell back to low triple digits before surging to a new high of 1,193.5% in May 2006.

- On 16 February 2006, the governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, Dr Gideon Gono, announced that the government had printed ZWD 21 trillion in order to buy foreign currency to pay off IMF arrears.

- In early May 2006, Zimbabwe's government began rolling the printing presses (once again) to produce about 60 trillion Zimbabwean dollars. The additional currency was required to finance the recent 300% increase in salaries for soldiers and policemen and 200% for other civil servants. The money was not budgeted for the current fiscal year, and the government did not say where it would come from.

- In August, 2006, the Zimbabwean government issued new currency and asked citizens to turn in old notes; the new currency (issued by the central bank of Zimbabwe) had three zeroes slashed from it. Most financial analysts remained skeptical and said that the new money would not provide relief from record inflation. [4]

See also

References