Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920): Difference between revisions

→Historical assessments: corrected minor typo: LLoyd to Lloyd |

|||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

| coordinates5 = {{coord|48.8239|2.2117}} |

| coordinates5 = {{coord|48.8239|2.2117}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The |

The Conference opened on 18 January 1919.<ref name="Erik Goldstein p49">Erik Goldstein ''The '''First''' World War Peace Settlements, 1919–1925'' p49 Routledge (2013)</ref> This date was symbolic, as it was the anniversary of the proclamation of [[William I, German Emperor|William I]] as [[German Emperor]] in 1871, in the [[Hall of Mirrors]] at the [[Palace of Versailles]], shortly before the end of the [[Siege of Paris (1870–71)|Siege of Paris]]<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-WZUAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA9|title=The First World War Peace Settlements, 1919-1925|last=Goldstein|first=Erik|date=2013-10-11|publisher=Routledge|isbn=9781317883678|language=en}}</ref> - a day itself imbued with significance in its turn in Germany as the anniversary of the establishment of the [[Kingdom of Prussia]] in 1701.<ref> |

||

{{cite book |

{{cite book |

||

| last1 = Ziolkowski |

| last1 = Ziolkowski |

||

Revision as of 16:25, 9 April 2019

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

The Paris Peace Conference, also known as Versailles Peace Conference, was the meeting of the victorious Allied Powers following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers.

Involving diplomats from 32 countries and nationalities, the major or main decisions were the creation of the League of Nations, as well as the five peace treaties with the defeated states; the awarding of German and Ottoman overseas possessions as "mandates", chiefly to Britain and France; reparations imposed on Germany; and the drawing of new national boundaries (sometimes with plebiscites) to better reflect ethnic boundaries.

The main result was the Treaty of Versailles with Germany, which in section 231 laid the guilt for the war on "the aggression of Germany and her allies". This provision proved humiliating for Germany and set the stage for the expensive reparations Germany was intended to pay (it paid only a small portion before reparations ended in 1931). The five major powers (France, Britain, Italy, Japan and the United States) controlled the Conference. The "Big Four" were French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, US President Woodrow Wilson, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando. They met together informally 145 times and made all the major decisions, which in turn were ratified by the others.[1] The conference began on 18 January 1919, and with respect to its end date Professor Michael Neiberg has noted:

Although the senior statesmen stopped working personally on the conference in June 1919, the formal peace process did not really end until July 1923, when the Treaty of Lausanne was signed".[2]

Overview and direct results

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2019) |

The Conference opened on 18 January 1919.[3] This date was symbolic, as it was the anniversary of the proclamation of William I as German Emperor in 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, shortly before the end of the Siege of Paris[4] - a day itself imbued with significance in its turn in Germany as the anniversary of the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701.[5] The Delegates from 27 nations (delegates representing 5 nationalities were for the most part ignored) were assigned to 52 commissions, which held 1,646 sessions to prepare reports, with the help of many experts, on topics ranging from prisoners of war to undersea cables, to international aviation, to responsibility for the war. Key recommendations were folded into the Treaty of Versailles with Germany, which had 15 chapters and 440 clauses, as well as treaties for the other defeated nations.

The five major powers (France, Britain, Italy, the U.S., and Japan) controlled the Conference. Amongst the "Big Five", in practice Japan only sent a former prime minister and played a small role; and the "Big Four" leaders dominated the conference.[6] The four met together informally 145 times and made all the major decisions, which in turn were ratified by other attendees.[1] The open meetings of all the delegations approved the decisions made by the Big Four. The conference came to an end on 21 January 1920 with the inaugural General Assembly of the League of Nations.[7][8]

Five major peace treaties were prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (with, in parentheses, the affected countries):

- the Treaty of Versailles, 28 June 1919, (Germany)

- the Treaty of Saint-Germain, 10 September 1919, (Austria)

- the Treaty of Neuilly, 27 November 1919, (Bulgaria)

- the Treaty of Trianon, 4 June 1920, (Hungary)

- the Treaty of Sèvres, 10 August 1920; subsequently revised by the Treaty of Lausanne, 24 July 1923, (Ottoman Empire/Republic of Turkey).

The major decisions were the establishment of the League of Nations; the five peace treaties with defeated enemies; the awarding of German and Ottoman overseas possessions as "mandates", chiefly to members of the British Empire and to France; reparations imposed on Germany, and the drawing of new national boundaries (sometimes with plebiscites) to better reflect the forces of nationalism. The main result was the Treaty of Versailles, with Germany, which in section 231 laid the guilt for the war on "the aggression of Germany and her allies". This provision proved humiliating for Germany and set the stage for very high reparations Germany was supposed to pay (it paid only a small portion before reparations ended in 1931).

As the conference's decisions were enacted unilaterally, and largely on the whims of the Big Four, for its duration Paris was effectively the center of a world government, which deliberated over and implemented the sweeping changes to the political geography of Europe. Most famously, the Treaty of Versailles itself weakened Germany's military and placed full blame for the war and costly reparations on Germany's shoulders – the humiliation and resentment in Germany is sometimes considered[by whom?] one of the causes of Nazi electoral successes and indirectly a cause of World War II. The League of Nations proved controversial in the United States as critics said it subverted the powers of Congress to declare war; the U.S. Senate did not ratify any of the peace treaties and the U.S. never joined the League – instead, the Harding administration of 1921-1923 concluded new treaties with Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Republican Germany was not invited to attend the conference at Versailles. Representatives of White Russia (but not Communist Russia) were present. Numerous other nations did send delegations in order to appeal for various unsuccessful additions to the treaties; parties lobbied for causes ranging from independence for the countries of the South Caucasus to Japan's unsuccessful demand for racial equality amongst the other Great Powers.

Mandates

A central issue of the Conference was the disposition of the overseas colonies of Germany. (Austria did not have colonies and the Ottoman Empire presented a separate issue.)[9][10]

The British dominions wanted their reward for their sacrifice. Australia wanted New Guinea, New Zealand wanted Samoa, and South Africa wanted South West Africa (modern Namibia). Wilson wanted the League of Nations to administer all the German colonies until such time as they were ready for independence. Lloyd George realized he needed to support his dominions, and he proposed a compromise that there be three types of mandates. Mandates for the Turkish provinces were one category; they would be divided up between Britain and France.

The second category, comprising New Guinea, Samoa, and South West Africa, were located so close to responsible supervisors that the mandates could hardly be given to anyone except Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Finally, the African colonies would need the careful supervision as "Class B" mandates that could only be provided by experienced colonial powers Britain, France, and Belgium; Italy and Portugal received small bits of territory. Wilson and the others finally went along with the solution.[11] The dominions received "Class C Mandates" to the colonies they wanted. Japan obtained mandates over German possessions north of the equator.[12][13][14]

Wilson wanted no mandates for the United States; his top advisor Colonel House was deeply involved in awarding the others.[15] Wilson was especially offended by Australian demands. He and Hughes had some memorable clashes, with the most famous being:

Wilson: "But after all, you speak for only five million people." Hughes: "I represent sixty thousand dead." (While the much larger United States had suffered fewer deaths – 50,000.)[16]

British approach

Maintenance of the British Empire's unity, holdings and interests were an overarching concern for the British delegates to the conference, but it entered the conference with the more specific goals of:

- Ensuring the security of France

- Removing the threat of the German High Seas Fleet

- Settling territorial contentions

- Supporting the League of Nations with that order of priority.[17]

The Racial Equality Proposal put forth by the Japanese did not directly conflict with any of these core British interests. However, as the conference progressed the full implications of the Racial Equality Proposal, regarding immigration to the British Dominions (with Australia taking particular exception), would become a major point of contention within the delegation.

Ultimately, Britain did not see the Racial Equality Proposal as being one of the fundamental aims of the conference. The delegation was therefore willing to sacrifice this proposal in order to placate the Australian delegation and thus help satisfy its overarching aim of preserving the unity of the British Empire.[18]

Although Britain reluctantly consented to the attendance of separate Dominion delegations, the British did manage to rebuff attempts by the envoys of the newly proclaimed Irish Republic to put its case to the Conference for self-determination, diplomatic recognition and membership of the proposed League of Nations. The Irish envoys' final "Demand for Recognition" in a letter to Clemenceau, the Chairman, was not answered.[19] Britain had planned to legislate for two Irish Home Rule states (without Dominion status), and did so in 1920. In 1919 Irish nationalists were unpopular with the Allies because of the Conscription Crisis of 1918[citation needed].

David Lloyd George commented that he did "not do badly" at the peace conference, "considering I was seated between Jesus Christ and Napoleon." This was a reference to the very idealistic views of Wilson on the one hand and the stark realism of Clemenceau, who was determined to see Germany punished.[20]

Dominion representation

The Dominion governments were not originally given separate invitations to the conference, but rather were expected to send representatives as part of the British delegation.[21]

Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, its Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, demanded that it have a separate seat at the conference. This was initially opposed not only by Britain but also by the United States, which saw a dominion delegation as an extra British vote. Borden responded by pointing out that since Canada had lost nearly 60,000 men, a far larger proportion of its men compared to the 50,000 American losses, at least had the right to the representation of a "minor" power. The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, eventually relented, and convinced the reluctant Americans to accept the presence of delegations from Canada, India, Australia, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa. They also received their own seats in the League of Nations.[22]

Canada, although it too had sacrificed nearly 60,000 men in the war, asked for neither reparations nor mandates.[23]

The Australian delegation, led by the Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, fought hard for its demands: reparations, the annexation of German New Guinea and rejection of the Japanese Racial Equality Proposal. Hughes said that he had no objection to the equality proposal provided it was stated in unambiguous terms that it did not confer any right to enter Australia. Hughes was concerned by the rise of Japan. Within months of the declaration of the War in 1914, Japan, Australia and New Zealand had seized all German possessions in the Far East and Pacific. Though Japan occupied German possessions with the blessings of the British, Hughes was alarmed by this policy.[24]

French approach

The French Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau, controlled his delegation and his chief goal was to weaken Germany militarily, strategically and economically.[25][26] Having personally witnessed two German attacks on French soil in the last forty years, he was adamant that Germany should not be permitted to attack France again. In particular, Clemenceau sought an American and British guarantee of French security in the event of another German attack.

Clemenceau also expressed skepticism and frustration with Wilson's Fourteen Points: "Mr. Wilson bores me with his fourteen points", complained Clemenceau. "Why, God Almighty has only ten!" Wilson won a few points by signing a mutual defense treaty with France, but back in Washington he did not present it to the Senate for ratification and it never took effect.[27]

Another alternative French policy was to seek a rapprochement with Germany. In May 1919 the diplomat René Massigli was sent on several secret missions to Berlin. During his visits Massigli offered on behalf of his government to revise the territorial and economic clauses of the upcoming peace treaty.[28] Massigli spoke of the desirability of "practical, verbal discussions" between French and German officials that would lead to a "collaboration Franco-allemande".[28] Furthermore, Massagli told the Germans that the French thought of the "Anglo-Saxon powers", namely the United States and British Empire, to be the major threat to France in the post-war world. He argued that both France and Germany had a joint interest in opposing "Anglo-Saxon domination" of the world and warned that the "deepening of opposition" between the French and the Germans "would lead to the ruin of both countries, to the advantage of the Anglo-Saxon powers".[29]

The Germans rejected the French offers because they considered the French overtures to be a trap to trick them into accepting the Versailles treaty "as is" and because the German foreign minister, Count Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau thought that the United States was more likely to reduce the severity of the peace terms than France.[29] In the final event it proved to be Lloyd George who pushed for more favourable terms for Germany.

Italian approach

In 1914 Italy remained neutral despite its alliance with Germany and Austria. In 1915 it joined the Allies. It was motivated by gaining the territories promised by the Allies in the secret Treaty of London: the Trentino, the Tyrol as far as Brenner, Trieste and Istria, most of the Dalmatian coast except Fiume, Valona and a protectorate over Albania, Antalya in Turkey and possibly colonies in Africa or Asia.

The Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando tried, therefore, to get full implementation of the Treaty of London, as agreed by France and Great Britain before the war. He had popular support, for the loss of 700,000 soldiers and a budget deficit of 12,000,000,000 Lire during the war made the Italian government and people feel entitled to all these territories and even more not mentioned in the Treaty of London, in particular the city of Fiume, which many Italians believed should be annexed to Italy because of the Italian population.[30]

In the meetings of the "Big Four", in which Orlando's powers of diplomacy were inhibited by his lack of English, the others were only willing to offer Trentino to the Brenner, the Dalmatian port of Zara and some of the Dalmatian islands. All other territories were promised to other nations and the great powers were worried about Italy's imperial ambitions. Even though Italy did get most of its demands, Orlando was refused Fiume, most of Dalmatia and any colonial gain, so he left the conference in a rage.[31]

There was a general disappointment in Italy, which the nationalist and fascist parties used to build the idea that Italy was betrayed by the Allies and refused what was due (Mutilated victory). This led to the general rise of Italian fascism.

American approach

Prior to Wilson's arrival in Europe in December 1918, no American president had ever visited Europe while in office.[32] Wilson's Fourteen Points, of a year earlier, had helped win the hearts and minds of many as the war ended; these included Americans and Europeans generally, as well as Germany, its allies and the former subjects of the Ottoman Empire specifically.

Wilson's diplomacy and his Fourteen Points had essentially established the conditions for the armistices that had brought an end to World War I. Wilson felt it was his duty and obligation to the people of the world to be a prominent figure at the peace negotiations. High hopes and expectations were placed on him to deliver what he had promised for the post-war era. In doing so, Wilson ultimately began to lead the foreign policy of the United States toward interventionism, a move strongly resisted in some domestic circles.

Once Wilson arrived, however, he found "rivalries, and conflicting claims previously submerged".[33] He worked mostly trying to sway the direction that the French (Georges Clemenceau) and British (Lloyd George) delegations were taking towards Germany and its allies in Europe, as well as the former Ottoman lands in the Middle East. Wilson's attempts to gain acceptance of his Fourteen Points ultimately failed, after France and Britain refused to adopt some specific points and its core principles.

In Europe, several of his Fourteen Points conflicted with the other powers. The United States did not encourage or believe that the responsibility for the war that Article 231 placed on Germany was fair or warranted.[34] It would not be until 1921 that the United States finally signed separate peace treaties with Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

In the Middle East, negotiations were complicated by competing aims, claims, and the new mandate system. The United States hoped to establish a more liberal and diplomatic world, as stated in the Fourteen Points, where democracy, sovereignty, liberty and self-determination would be respected. France and Britain, on the other hand, already controlled empires, wielded power over their subjects around the world and still aspired to be dominant colonial powers.

In light of the previously secret Sykes–Picot Agreement, and following the adoption of the mandate system on the Arab province of the former Ottoman lands, the conference heard statements from competing Zionist and Arab claimants. President Woodrow Wilson then recommended an international commission of inquiry to ascertain the wishes of the local inhabitants. The Commission idea, first accepted by Great Britain and France, was later rejected. Eventually it became the purely American King–Crane Commission, which toured all Syria and Palestine during the summer of 1919, taking statements and sampling opinion.[33] Its report, presented to President Wilson, was kept secret from the public until The New York Times broke the story in December 1922.[35] A pro-Zionist joint resolution on Palestine was passed by Congress in September 1922.[36]

France and Britain tried to appease the American President by consenting to the establishment of his League of Nations. However, because isolationist sentiment was strong and some of the articles in the League's charter conflicted with the United States Constitution, the United States never ratified the Treaty of Versailles nor joined the League of Nations,[37] which President Wilson had helped create, to further peace through diplomacy rather than war and conditions which can breed it.

Under President Warren Harding the United States signed separate treaties with Germany,[38] Austria,[39] and Hungary[40] in 1921.

Japanese approach

Japan sent a large delegation headed by the former Prime Minister, Marquis Saionji Kinmochi. It was originally one of the "big five" but relinquished that role because of its slight interest in European affairs. Instead it focused on two demands: the inclusion of their Racial Equality Proposal in the League's Covenant and Japanese territorial claims with respect to former German colonies, namely Shantung (including Kiaochow) and the Pacific islands north of the Equator (the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, the Mariana Islands, and the Carolines). The former Foreign Minister Baron Makino Nobuaki was de facto chief while Saionji's role was symbolic and limited by his ill health. The Japanese delegation became unhappy after receiving only one-half of the rights of Germany, and walked out of the conference.[41]

Racial equality proposal

Japan proposed the inclusion of a "racial equality clause" in the Covenant of the League of Nations on 13 February as an amendment to Article 21.[42] It read:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.

President Wilson knew that Great Britain was critical to the decision and he, as Conference chairman, ruled that a unanimous vote was required. On 11 April 1919, the commission held a final session and the proposal received a majority of votes, but Great Britain and Australia opposed it. The Australians had lobbied the British to defend Australia's White Australia policy. Wilson also knew that domestically he needed the support of the US western states who feared Japanese and Chinese immigration and the southern states who feared the rise of their black citizens.[43] The defeat of the proposal influenced Japan's turn from cooperation with the West toward more nationalistic policies.[44]

Territorial claims

The Japanese claim to Shantung was disputed by the Chinese. In 1914 at the outset of World War I Japan had seized the territory granted to Germany in 1897. They also seized the German islands in the Pacific north of the equator. In 1917, Japan had made secret agreements with Britain, France, and Italy that guaranteed their annexation of these territories. With Britain, there was a mutual agreement, Japan also agreeing to support British annexation of the Pacific islands south of the equator. Despite a generally pro-Chinese view on behalf of the American delegation, Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles transferred German concessions in Jiaozhou Bay, China to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to China. The leader of the Chinese delegation, Lou Tseng-Tsiang, demanded that a reservation be inserted before he would sign the treaty. The reservation was denied, and the treaty was signed by all the delegations except that of China. Chinese outrage over this provision led to demonstrations known as the May Fourth Movement. The Pacific islands north of the equator became a class C mandate administered by Japan.[45]

Greek approach

Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos took part in the Paris Peace Conference as Greece's chief representative. President Woodrow Wilson was said to have placed Venizelos first in point of personal ability among all delegates gathered in Paris to settle the terms of Peace.[46]

Venizelos proposed the Greek expansion on Thrace and Asia Minor (lands of the defeated Kingdom of Bulgaria and Ottoman Empire), Northern Epirus, Imvros and Tenedos, aiming to the realization of the Megali Idea. He also reached an agreement with the Italians on the cession of the Dodecanese (Venizelos–Tittoni agreement). For the Greeks of Pontus he proposed a common Pontic-Armenian State.

As a liberal politician, Venizelos was a strong supporter of the Fourteen Points and of the League of Nations.

Chinese approach

The Chinese delegation was led by Lou Tseng-Tsiang, accompanied by Wellington Koo and Cao Rulin. Before the Western powers, Koo demanded that Germany's concessions on Shandong be returned to China. He further called for an end to imperialist institutions such as extraterritoriality, legation guards, and foreign leaseholds. Despite American support and the ostensible spirit of self-determination, the Western powers refused his claims, transferring the German concessions to Japan instead. This sparked widespread student protests in China on 4 May, later known as the May Fourth Movement, eventually pressuring the government into refusing to sign the Treaty of Versailles. Thus the Chinese delegation at the Paris Peace Conference was the only one not to sign the treaty at the signing ceremony.[47]

Questions about independence

All-Russian Government (Whites)

While Russia was formally excluded from the Conference,[48] despite having fought the Central Powers for three years, the Russian Provincial Council (chaired by Prince Lvov[49]), the successor to the Russian Constituent Assembly and the political arm of the Russian White movement attended the conference. It was represented by the former Tsarist minister Sergey Sazonov[3] who, if the Tsar had not been overthrown, would most likely have attended the conference anyway. The Council maintained the position of an indivisible Russia, but some were prepared to negotiate over the loss of Poland and Finland.[50] The Council suggested all matters relating to territorial claims, or demands for autonomy within the former Russian Empire, be referred to a new All-Russian Constituent Assembly.

Ukraine

Ukraine had its best opportunity to win recognition and support from foreign powers at the Conference of 1919.[51] At a meeting of the Big Five on 16 January, Lloyd George called Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura (1874–1926) an adventurer and dismissed Ukraine as an anti-Bolshevik stronghold. Sir Eyre Crowe, British undersecretary of state for foreign affairs, spoke against a union of East Galicia and Poland. The British cabinet never decided whether to support a united or dismembered Russia. The United States was sympathetic to a strong, united Russia as a counterpoise to Japan, but Britain feared a threat to India. Petliura appointed Count Tyshkevich his representative to the Vatican, and Pope Benedict XV recognized Ukrainian independence. Ukraine was effectively ignored.[52]

Belarus

A Delegation of the Belarusian Democratic Republic under Prime Minister Anton Łuckievič also participated in the conference, attempting to gain international recognition of the independence of Belarus. On the way to the conference, the delegation was received by Czechoslovak president Tomáš Masaryk in Prague. During the conference, Łuckievič had meetings with the exiled Foreign Minister of admiral Kolchak's Russian government Sergey Sazonov and the Prime Minister of Poland Ignacy Jan Paderewski.[53]

Minority rights in Poland and other European countries

At the insistence of President Wilson, the Big Four required Poland to sign a treaty on 28 June 1919 that guaranteed minority rights in the new nation. Poland signed under protest and made little effort to enforce the specified rights for Germans, Jews, Ukrainians, and other minorities. Similar treaties were signed by Czechoslovakia, Romania, Yugoslavia, Greece, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and later by Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. Estonia had already given cultural autonomy to minorities in its declaration of independence. Finland and Germany were not asked to sign a minority rights treaty.[54]

In Poland, the key provisions were to become fundamental laws that overrode any national legal codes or legislation. The new country pledged to assure "full and complete protection of life and liberty to all individuals...without distinction of birth, nationality, language, race, or religion." Freedom of religion was guaranteed to everyone. Most residents were given citizenship, but there was considerable ambiguity on who was covered. The treaty guaranteed basic civil, political, and cultural rights, and required all citizens to be equal before the law and enjoy identical rights of citizens and workers. Polish was of the national language, but the treaty provided that minority languages could be freely used privately, in commerce, religion, the press, at public meetings, and before all courts. Minorities were to be permitted to establish and control at their own expense private charities, churches and social institutions, as well as schools, without interference from the government. The government was required to set up German-language public schools in those districts that had been German territory before the war. All education above the primary level was to be conducted exclusively in the national language. Article 12 was the enforcement clause; it gave the Council of the League of Nations responsibility for monitoring and enforcing each treaty.[55][56]

Caucasus

The three South Caucasian republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia as well as the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus each sent a delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Their attempts to gain protection from threats posed by the ongoing Russian Civil War largely failed as none of the major powers was interested in taking a mandate over the Caucasian territories. After a series of delays, the three South Caucasian countries ultimately gained de facto recognition from the Supreme Council of the Allied powers, but only when all European troops had been withdrawn from the Caucasus except for a British contingent in Batumi. Georgia was recognized de facto on 12 January 1920, followed by Azerbaijan on the same day and Armenia on 19 January 1920. The Allied leaders decided to limit their assistance to the Caucasian republics to arms, munitions, and food supply.[57]

The Armenian delegation was represented by Avetis Aharonyan, Hamo Ohanjanyan, Armen Garo and others. Azerbaijan's mission was headed by Alimardan Topchubashev. The delegation from Georgia included Nikolay Chkheidze, Irakli Tsereteli, Zurab Avalishvili, and others.

Korean Delegation

After a failed attempt by the Korean National Association to send a three-man delegation to Paris, a delegation of Koreans from China and Hawaii did make it there. Included in this delegation, was a representative from the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai, Kim Kyu-sik.[58] They were aided by the Chinese, who were eager for the opportunity to embarrass Japan at the international forum. Several top Chinese leaders at the time, including Sun Yat-sen, told U.S. diplomats that the peace conference should take up the question of Korean independence. Beyond that, however, the Chinese, locked in a struggle against the Japanese themselves, could do little for Korea.[59] Apart from China, no nation took the Koreans seriously at the Paris conference because of its status as a Japanese colony.[60] The failure of the Korean nationalists to gain support from the Paris Peace Conference ended the possibility of foreign support.[61]

Palestine

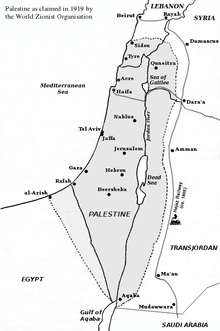

Following the Conference's decision to separate the former Arab provinces from the Ottoman Empire and to apply the newly conceived mandate-system to them, the Zionist Organization submitted their draft resolutions for consideration by the Peace Conference on 3 February 1919.

The statement included five main points:[62]

- Recognition of the Jewish people's historic title to Palestine and their right to reconstitute their National Home there.

- The boundaries of Palestine were to be declared as set out in the attached Schedule

- The sovereign possession of Palestine would be vested in the League of Nations and the Government entrusted to Great Britain as Mandatory of the League.

- Other provisions to be inserted by the High Contracting Parties relating to the application of any general conditions attached to mandates, which are suitable to the case in Palestine.

- The mandate shall be subject also to several noted special conditions, including

- promotion of Jewish immigration and close settlement on the land and safeguarding rights of the present non-Jewish population

- a Jewish Council representative for the development of the Jewish National Home in Palestine, and offer to the Council in priority any concession for public works or for the development of natural resources

- self-government for localities

- freedom of religious worship; no discrimination among the inhabitants with regard to citizenship and civil rights, on the grounds of religion, or of race

- control of the Holy Places

However, despite these attempts to influence the conference, the Zionists were instead constrained by Article 7 of the resulting Palestine Mandate to merely having the right of obtaining Palestinian citizenship: "The Administration of Palestine shall be responsible for enacting a nationality law. There shall be included in this law provisions framed so as to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take up their permanent residence in Palestine."[63]

Citing the Balfour Declaration, the Zionists suggested that the British had already recognized the historic title of the Jews to Palestine in 1917.[62] The preamble of the British Mandate of 1922, in which the Balfour Declaration was incorporated, stated: "Whereas recognition has thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country ...".[64]

Women's approach

An unprecedented aspect of the Paris Peace Conference was concerted pressure brought to bear on delegates by a committee of women seeking to establish and entrench women's fundamental social, economic, and political rights, including but not limited to suffrage, within the Paris peace framework. Although denied seats at the Paris Conference, under the leadership of Marguerite de Witt-Schlumberger, president of the French Union for Women's Suffrage, an Inter-Allied Women's Conference (IAWC) was convened and met from 10 February to 10 April 1919. The IAWC lobbied Woodrow Wilson, and later all delegates of the Paris Conference, to admit women to its committees, and was successful in achieving a hearing from the conference's Commissions for International Labour Legislation, and, later, from the League of Nations Commission. One key and concrete outcome of the work of the IAWC was Article 7 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, which states that "All positions under or in connection with the League, including the Secretariat, shall be open equally to men and women." More generally, the IAWC placed the issue of women's rights at the centre of the new world order established in Paris.[65][66]

Historical assessments

The remaking of the world map at these conferences gave birth to a number of critical conflict-prone international contradictions, which would become one of the causes of World War II.[67] The British historian Eric Hobsbawm claimed:

[N]o equally systematic attempt has been made before or since, in Europe or anywhere else, to redraw the political map on national lines. [...] The logical implication of trying to create a continent neatly divided into coherent territorial states each inhabited by separate ethnically and linguistically homogeneous population, was the mass expulsion or extermination of minorities. Such was and is the reductio ad absurdum of nationalism in its territorial version, although this was not fully demonstrated until the 1940s.[68]

Historians on the left have argued that Wilson's Fourteen Points, in particular, the principle of national self-determination, were primarily anti-Left measures, designed to tame the revolutionary fever sweeping across Europe in the wake of the October Revolution and the end of the war by playing the nationalist card.[69]

British Historian Antony Lentin evaluates Lloyd George's role in Paris as a major success:

- Unrivaled as a negotiator, he had powerful combative instincts and indomitable determinism, and succeeded through charm, insight, resourcefulness, and simple pugnacity. Although sympathetic to France's desires to keep Germany under control, he did much to prevent the French from gaining power, attempted to extract Britain from the Anglo-French entente, inserted the war-guilt clause, and maintained a liberal and realist view of the postwar world. By doing so, he managed to consolidate power over the House [of Commons], secured his power base, expanded the empire, and sought a European balance of power.[70]

Cultural references

- World's End (1940), the first novel in Upton Sinclair's Pulitzer Prize-winning Lanny Budd series, describes the political machinations and consequences of the Paris Peace Conference through much of the book's second half, with Sinclair's narrative including many historically accurate characters and events.

- The first two books of novelist Robert Goddard's The Wide World trilogy (The Ways of the World and The Corners of the Globe) are centered around the diplomatic machinations which form the background to the conference.

- Paris 1919 (1973), the third studio album by Welsh musician John Cale, is named after the Paris Peace Conference, and its title song explores various aspects of early-20th-century culture and history in Western Europe.

- A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia (1992) is a British television film starring Ralph Fiennes as T. E. Lawrence and Alexander Siddig as Emir Faisal, depicting their struggles to secure an independent Arab state at the conference.

- "Paris, May 1919" is a 1993 episode of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, written by Jonathan Hales and directed by David Hare, in which Indiana Jones is shown working as a translator with the American delegation at the Paris Peace Conference.

See also

References

- ^ a b Rene Albrecht-Carrie, Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna (1958) p. 363

- ^ Michael S. Neiberg (2017). The Treaty of Versailles: A Concise History. Oxford University Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-19-065918-9.

- ^ a b Erik Goldstein The First World War Peace Settlements, 1919–1925 p49 Routledge (2013)

- ^ Goldstein, Erik (11 October 2013). The First World War Peace Settlements, 1919-1925. Routledge. ISBN 9781317883678.

- ^

Ziolkowski, Theodore (2007). "6: The God That Failed". Modes of Faith: Secular Surrogates for Lost Religious Belief. Accessible Publishing Systems PTY, Ltd (published 2011). p. 231. ISBN 9781459627376. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

[...] Ebert persuaded the various councils to set elections for 19 January 1919 (the day following a date symbolic in Prussian history ever since the Kingdom of Prussia was established on 18 January 1701).

- ^

Meehan, John David (2005). "4: Failure at Geneva". The Dominion and the Rising Sun: Canada Encounters Japan, 1929-41. Vancouver: UBC Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 9780774811217. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

As the first non-European nation to achieve great-power status, Japan took its place alongside the other Big Five at Versailles, even if it was often a silent partner.

- ^ Antony Lentin, "Germany: a New Carthage?" History Today (2012) 62#1 pp. 22–27 online

- ^ Paul Birdsall, Versailles Twenty Years After (1941) is a convenient history and analysis of the conference. Longer and more recent is Margaret Macmillan, Peacemakers: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War (2002), also published as Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (2003); a good short overview is Alan Sharp, The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923 (2nd ed. 2008)

- ^ Alan Sharp, The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking After the First World War, 1919–1923 (2nd ed. 2008) ch 7

- ^ Andrew J. Crozier, "The Establishment of the Mandates System 1919–25: Some Problems Created by the Paris Peace Conference," Journal of Contemporary History (1979) 14#3 pp 483–513 in JSTOR.

- ^ Peter Ryland, Lloyd George (1975) p. 481

- ^ Wm Louis, Roger (1966). "Australia and the German Colonies in the Pacific, 1914–1919". Journal of Modern History. 38 (4): 407–421. doi:10.1086/239953. JSTOR 1876683.

- ^ Paul Birdsall, Versailles Twenty Years After (1941) pp. 58–82

- ^ Macmillan, Paris 1919, pp. 98–106

- ^ Scot David Bruce, Woodrow Wilson's Colonial Emissary: Edward M. House and the Origins of the Mandate System, 1917–1919 (University of Nebraska Press, 2013)

- ^ Mungo MacCallum (2013). The Good, the Bad and the Unlikely: Australia's Prime Ministers. Black Inc. p. 38.

- ^ Zara S. Steiner (2007). The Lights that Failed: European International History, 1919–1933. Oxford UP. pp. 481–82.

- ^ Shimazu (1998), pp. 14–15, 117.

- ^ "Official Memorandum in support of Ireland's demand for recognition as a sovereign independent state. Presented to Georges Clemenceau and the members of the Paris Peace Conference by Sean T O'Ceallaigh and George Gavan Duffy from O Ceallaigh Gavan Duffy to George Clemenceau – June 1919. – Documents on IRISH FOREIGN POLICY".

- ^ John C. Hulsman (2009). To Begin the World Over Again: Lawrence of Arabia from Damascus to Baghdad. pp. 119–20.

- ^ Snelling, R. C. (1975). "Peacemaking, 1919: Australia, New Zealand and the British Empire Delegation at Versailles". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 4 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1080/03086537508582446.

- ^ Fitzhardinge, L. F. (1968). "Hughes, Borden, and Dominion Representation at the Paris Peace Conference". Canadian Historical Review. 49 (2): 160–169. doi:10.3138/chr-049-02-03.

- ^ Margaret McMillan, "Canada and the Peace Settlements," in David Mackenzie, ed., Canada and the First World War (2005) pp. 379–408

- ^ Snelling, R. C. (1975). "Peacemaking, 1919: Australia, New Zealand and the British Empire delegation at Versailles". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 4 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1080/03086537508582446.

- ^ MacMillan, Paris 1919 pp 26–35

- ^ David Robin Watson, Georges Clemenceau (1974) pp 338–65

- ^ Ambrosius, Lloyd E. (1972). "Wilson, the Republicans, and French Security after World War I". Journal of American History. 59 (2): 341–352. doi:10.2307/1890194. JSTOR 1890194.

- ^ a b Trachtenberg, Marc (1979). "Reparation at the Paris Peace Conference". Journal of Modern History. 51 (1): 24–55 [p. 42]. doi:10.1086/241847. JSTOR 1877867.

- ^ a b Trachtenberg (1979), page 43.

- ^ Macmillan, ch 22

- ^ H. James Burgwyn, Legend of the Mutilated Victory: Italy, the Great War and the Paris Peace Conference, 1915–1919 (1993)

- ^ MacMillan (2001), p. 3.

- ^ a b US Dept of State; International Boundary Study, Jordan – Syria Boundary, No. 94 – 30 December 1969, p.10 Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ MacMillan, Paris 1919 (2001), p. 6.

- ^ Ellis, William (3 December 1922). "CRANE AND KING'S LONG-HID REPORT ON THE NEAR EAST - American Mandate Recommended in DocumentSent to Wilson.PEOPLE CALLED FOR USDisliked French, DistrustedBritish and Opposed theZionist Plan.ALLIES AT CROSS PURPOSES Our Control Would Have Hid Its Seat in Constantinople, Dominating New Nations. - Article - NYTimes.com". New York Times.

- ^ Rubenberg, Cheryl (1986). Israel and the American National Interest: A Critical Examination. University of Illinois Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-252-06074-1.

- ^ MacMillan (2001), p. 83.

- ^ Wikisource

- ^ "First World War.com – Primary Documents – U.S. Peace Treaty with Austria, 24 August 1921". Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "First World War.com – Primary Documents – U.S. Peace Treaty with Hungary, 29 August 1921". Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ Macmillan, ch 23

- ^ Gordon Lauren, Paul (1978). "Human Rights in History: Diplomacy and Racial Equality at the Paris Peace Conference". Diplomatic History. 2 (3): 257–278. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1978.tb00435.x.

- ^ "Racial Equality Amendment, Japan". encyclopedia.com. 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Macmillan, Paris 1919 p. 321

- ^ Fifield, Russell. "Japanese Policy toward the Shantung Question at the Paris Peace Conference," Journal of Modern History (1951) 23:3 pp 265–272. in JSTOR reprint primary Japanese sources

- ^ Chester, 1921, p. 6

- ^ MacMillan, Paris of 1919 pp 322–45

- ^ Seth P. Tillman Anglo-American Relations at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 p136 Princeton University Press (1961)

- ^ John M. Thompson Russia, Bolshevism, and the Versailles peace p76 Princeton University Press (1967)

- ^ John M. Thompson Russia, Bolshevism, and the Versailles peace p78 Princeton University Press (1967)

- ^ Laurence J. Orzell, "A 'Hotly Disputed' Issue: Eastern Galicia At The Paris Peace Conference, 1919," Polish Review (1980): 49–68. in JSTOR

- ^ Yakovenko, Natalya (2002). "Ukraine in British Strategies and Concepts of Foreign Policy, 1917–1922 and after". East European Quarterly. 36 (4): 465–479.

- ^ Моладзь БНФ. "Чатыры ўрады БНР на міжнароднай арэне ў 1918–1920 г." Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fink, Carole (1996). "The Paris Peace Conference and the Question of Minority Rights". Peace and Change: A journal of peace research. 21 (3): 273–88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0130.1996.tb00272.x.

- ^ Fink, "The Paris Peace Conference and the Question of Minority Rights"

- ^ Edmund Jan Osmańczyk (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: A to F. Routledge. p. 1812.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The making of the Georgian nation (2 ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0253209153.

- ^ Hart-Landsberg, Martin (1998). Korea: Division, Reunification, & U.S. Foreign Policy Monthly Review Press. P. 30.

- ^ Manela, Erez (2007) The Wilsonian Moment pp. 119–135, 197–213.

- ^ Kim, Seung-Young (2009). American Diplomacy and Strategy Toward Korea and Northeast Asia, 1882–1950 and After pp 64–65.

- ^ Baldwin, Frank (1972). The March First Movement: Korean Challenge and Japanese Response

- ^ a b Statement of the Zionist Organization regarding Palestine Archived 24 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 3 February 1919

- ^ "The Avalon Project : The Palestine Mandate".

- ^ Avalon Project, The Palestine Mandate

- ^ Siegel, Mona L. (6 January 2019). In the Drawing Rooms of Paris: The Inter-Allied Women’s Conference of 1919. American Historical Association 133rd Meeting.

- ^ "The Covenant of the League of Nations". Avalon project. Yale Law School - Lillian Goldman Law Library.

- ^ First World War – Willmott, H. P., Dorling Kindersley, 2003, pp. 292–307.

- ^ Hobsbawm 1992, p. 133.

- ^ Hobsbawm 1994, p. 67: "[T]he first Western reaction to the Bolsheviks' appeal to the peoples to make peace—and their publication of the secret treaties in which the Allies had carved up Europe among themselves—had been President Wilson's Fourteen Points, which played the nationalist card against Lenin's international appeal. A zone of small nation-states was to form a sort of quarantine belt against the Red virus. ... [T]he establishment of new small nation-states along Wilsonian lines, though far from eliminating national conflicts in the zone of revolutions, ... diminished the scope for Bolshevik revolution. That, indeed, had been the intention of the Allied peacemakers."

From the other side of the political spectrum, John Lewis Gaddis likewise writes: "When Woodrow Wilson made the principle of self-determination one of this Fourteen Points his intent had been to undercut the appeal of Bolshevism" (Gaddis 2005, p. 121).

This view has a long history, and can be summarised by Ray Stannard Baker's famous remark that "Paris cannot be understood without Moscow." See McFadden 1993, p. 191.

- ^ Antony Lentin, "Several types of ambiguity: Lloyd George at the Paris peace conference." Diplomacy and Statecraft 6.1 (1995): 223-251.

Further reading

- Albrecht-Carrie, Rene. Italy at the Paris Peace Conference (1938) online edition

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. Woodrow Wilson and the American Diplomatic Tradition: The Treaty Fight in Perspective (1990)

- Andelman, David A. A Shattered Peace: Versailles 1919 and the Price We Pay Today (2007) popular history that stresses multiple long-term disasters caused by Treaty.

- Bailey; Thomas A. Wilson and the Peacemakers: Combining Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace and Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1947) online edition

- Birdsall, Paul. Versailles twenty years after (1941) well balanced older account

- Boemeke, Manfred F., et al., eds. The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment after 75 Years (1998). A major collection of important papers by scholars

- Bruce, Scot David, Woodrow Wilson's Colonial Emissary: Edward M. House and the Origins of the Mandate System, 1917–1919 (University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

- Clements, Kendrick, A. Woodrow Wilson: World Statesman (1999)

- Cooper, John Milton. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009), scholarly biography; pp 439–532 excerpt and text search

- Dillon, Emile Joseph. The Inside Story of the Peace Conference, (1920) online

- Dockrill, Michael, and John Fisher. The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: Peace Without Victory? (Springer, 2016).

- Ferguson, Niall. The Pity of War: Explaining World War One (1999), economics issues at Paris pp 395–432

- Doumanis, Nicholas, ed. The Oxford Handbook of European History, 1914–1945 (2016) ch 9.

- Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace, The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, Macmillan 1989.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (2005). The Cold War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-713-99912-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gelfand, Lawrence Emerson. The Inquiry: American Preparations for Peace, 1917–1919 (Yale UP, 1963).

- Ginneken, Anique H.M. van. Historical Dictionary of the League of Nations (2006)

- Henig, Ruth. Versailles and After: 1919–1933 (2nd ed. 1995), 100 pages; brief introduction by scholar

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (1992). Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Canto (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43961-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hobsbawm, E.J. (1994). The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 978-0718133078.

- Keynes, John Maynard, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1920) famous criticism by leading economist full text online

- Dimitri Kitsikis, Le rôle des experts à la Conférence de la Paix de 1919, Ottawa, éditions de l'université d'Ottawa, 1972.

- Dimitri Kitsikis, Propagande et pressions en politique internationale. La Grèce et ses revendications à la Conférence de la Paix, 1919–1920, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1963.

- Knock, Thomas J. To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order (1995)

- Lederer, Ivo J., ed. The Versailles Settlement—Was It Foredoomed to Failure? (1960) short excerpts from scholars online edition

- Lentin, Antony. Guilt at Versailles: Lloyd George and the Pre-history of Appeasement (1985)

- Lentin, Antony. Lloyd George and the Lost Peace: From Versailles to Hitler, 1919–1940 (2004)

- Macalister-Smith, Peter, Schwietzke, Joachim: Diplomatic Conferences and Congresses. A Bibliographical Compendium of State Practice 1642 to 1919, W. Neugebauer, Graz, Feldkirch 2017, ISBN 978-3-85376-325-4.

- McFadden, David W. (1993). Alternative Paths: Soviets and Americans, 1917–1920. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-36115-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacMillan, Margaret. Peacemakers: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War (2001), also published as Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (2003); influential survey

- Mayer, Arno J. (1967). Politics and Diplomacy of Peacemaking: Containment and Counterrevolution at Versailles, 1918–1919. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Nicolson, Harold (2009) [1933]. Peacemaking, 1919. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-25604-4. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Paxton, Robert O., and Julie Hessler. Europe in the Twentieth Century (2011) pp 141–78

- Marks, Sally. The Illusion of Peace: International Relations in Europe 1918–1933 (2nd ed. 2003)

- Mayer, Arno J., Politics and Diplomacy of Peacemaking: Containment and Counter-revolution at Versailles, 1918–1919 (1967), leftist

- Newton, Douglas. British Policy and the Weimar Republic, 1918–1919 (1997). 484 pgs.

- Pellegrino, Anthony; Dean Lee, Christopher; Alex (2012). "Historical Thinking through Classroom Simulation: 1919 Paris Peace Conference". The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas. 85 (4): 146–152.

- Roberts, Priscilla. "Wilson, Europe's Colonial Empires, and the Issue of Imperialism," in Ross A. Kennedy, ed., A Companion to Woodrow Wilson (2013) pp: 492–517.

- Schwabe, Klaus. Woodrow Wilson, Revolutionary Germany, and Peacemaking, 1918–1919: Missionary Diplomacy and the Realities of Power (1985) online edition

- Sharp, Alan. The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923 (2nd ed. 2008)

- Sharp, Alan (2005). "The Enforcement Of The Treaty Of Versailles, 1919–1923". Diplomacy and Statecraft. 16 (3): 423–438. doi:10.1080/09592290500207677.

- Naoko Shimazu (1998), Japan, Race and Equality, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-17207-1

- Steiner, Zara. The Lights that Failed: European International History 1919–1933 (Oxford History of Modern Europe) (2007), pp 15–79; major scholarly work online at Questia

- Trachtenberg, Marc (1979). "Reparations at the Paris Peace Conference". The Journal of Modern History. 51 (1): 24–55. doi:10.1086/241847. JSTOR 1877867.

- Walworth, Arthur. Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 (1986) 618pp online edition

- Walworth, Arthur (1958). Woodrow Wilson, Volume I, Volume II. Longmans, Green.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); 904pp; full scale scholarly biography; winner of Pulitzer Prize; online free; 2nd ed. 1965 - Watson, David Robin. George Clemenceau: A Political Biography (1976) 463 pgs. online edition

External links

- Sharp, Alan: The Paris Peace Conference and its Consequences , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Excerpts from the NFB documentary Paris 1919

- Sampling of maps used by the American delegates held by the American Geographical Society Library, UW Milwaukee