German invasion of Belgium (1914)

| German invasion of Belgium | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||||

German invasion of Belgium | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 750,000 men |

Belgium: 220,000 men Britain: 247,400 men France: 299,000 men Total: 766,400 men | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 20,000[citation needed] | 30,000[citation needed] | ||||||||

| 6,000 civilians killed[citation needed] | |||||||||

The German invasion of Belgium was a military campaign which began on 4 August 1914. Earlier, on 24 July, the Belgian government had announced that if war came it would uphold its historic neutrality. The Belgian government mobilised its armed forces on 31 July and a state of heightened alert (Kriegsgefahr) was proclaimed in Germany. On 2 August, the German government sent an ultimatum to Belgium, demanding passage through the country, and German forces invaded Luxembourg. Two days later, the Belgian government refused the demands and the British government guaranteed military support to Belgium. The German government declared war on Belgium on 4 August, troops crossed the border and began the Battle of Liège.

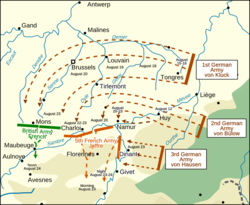

German military operations in Belgium were intended to bring the 1st, 2nd and 3rd armies into positions in Belgium from which they could invade France, which, after the fall of Liège on 7 August, led to sieges of Belgian fortresses along the river Meuse at Namur and the surrender of the last forts (16–17 August). The government abandoned the capital, Brussels, on 17 August and after fighting on the Gete river, the Belgian field army withdrew westwards to the National Redoubt at Antwerp on 19 August. Brussels was occupied the following day and the Siege of Namur began on 21 August.

After the Battle of Mons and the Battle of Charleroi, the bulk of the German armies marched south into France, leaving small forces to garrison Brussels and the Belgian railways. The III Reserve Corps advanced to the fortified zone around Antwerp and a division of the IV Reserve Corps took over in Brussels. The Belgian field army made several sorties from Antwerp in late August and September to harass German communications and to assist the French and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), by keeping German troops in Belgium. German troop withdrawals to reinforce the main armies in France were postponed to repulse a Belgian sortie from 9 to 13 September and a German corps in transit was retained in Belgium for several days. Belgian resistance and German fear of francs-tireurs, led the Germans to implement a policy of terror (schrecklichkeit) against Belgian civilians soon after the invasion, in which massacres, executions, hostage taking and the burning of towns and villages took place and became known as the Rape of Belgium.

After the Battle of the Frontiers ended, the French armies and the BEF began the Great Retreat into France (24 August – 28 September), the Belgian army and small detachments of French and British troops fought in Belgium against German cavalry and Jäger. On 27 August, a squadron of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) flew to Ostend, to conduct air reconnaissance between Bruges, Ghent and Ypres. Royal Marines landed in France on 19–20 September and began scouting unoccupied Belgium in motor cars; an RNAS Armoured Car Section was created by fitting vehicles with bulletproof steel. On 2 October, the Marine Brigade of the Royal Naval Division was moved to Antwerp, followed by the rest of the division on 6 October. From 6 to 7 October, the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division landed at Zeebrugge and naval forces collected at Dover were formed into the Dover Patrol, to operate in the Channel and off the French–Belgian coast. Despite minor British reinforcement, the Siege of Antwerp ended when its defensive ring of forts was destroyed by German super-heavy artillery. The city was abandoned on 9 October and Allied forces withdrew to West Flanders.

At the end of the Great Retreat, the Race to the Sea (17 September – 19 October) began, a period of reciprocal attempts by the Germans and Franco-British to outflank their opponents, extending the front line northwards from the Aisne, into Picardy, Artois and Flanders. Military operations in Belgium also moved westwards as the Belgian army withdrew from Antwerp to the area close to the border with France. The Belgian army fought the defensive Battle of the Yser (16–31 October) from Nieuwpoort (Nieuport) south to Diksmuide (Dixmude), as the German 4th Army attacked westwards and French, British and some Belgian troops fought the First Battle of Ypres (19 October – 22 November) against the 4th and 6th armies. By November 1914, most of Belgium was under German occupation and Allied naval blockade. A German military administration was established on 26 August 1914, to rule through the pre-war Belgian administrative system, overseen by a small group of German officers and officials. Belgium was divided into administrative zones, the General Government of Brussels and its hinterland; a second zone, under the 4th Army, including Ghent and Antwerp and a third zone under the German Navy along the coastline. The German occupation lasted until late 1918.

Background

Belgian neutrality

The 1839 Treaty of London recognised Belgium as an independent and neutral state.[1] Until 1911, Belgian strategic analysis anticipated that if war came, the Germans would attack France across the Franco-German border and trap the French armies against the Belgian frontier, as they had done in 1870. British and French guarantees of Belgian independence were made before 1914 but the possibility of landings in Antwerp was floated by the British military attaché in 1906 and 1911, which led the Belgians to suspect that the British had come to see Belgian neutrality as a matter of British diplomatic and military advantage, rather than as an end in itself. The Agadir Crisis (1911) left the Belgian government in little doubt as to the risk of a European war and an invasion of Belgium by Germany.[2]

In September 1911, a government meeting concluded that Belgium must be prepared to resist a German invasion, to avoid accusations of collusion by the British and French governments. Britain, France and the Netherlands were also to continue to be treated as potential enemies.[2] In 1913 and 1914, the Germans made inquires to the Belgian military attaché in Berlin, about the passage of German military forces through Belgium. If invaded, Belgium would need foreign help but would not treat foreign powers as allies or form objectives beyond the maintenance of Belgian independence. Neutrality forced the Belgian government into a strategy of military independence, based on a rearmament programme begun in 1909, which was expected to be complete in 1926. The Belgian plan was to have three army corps, to reduce the numerical advantage of the German armies over the French, intended to deter a German invasion.[3]

Conscription was introduced in 1909 but with a reduction in the term of service to fifteen months; the Agadir Crisis made the government continue its preparations but until 1913, the size of the army was not fixed as a proportion of the population. The annual conscription of 13,300 recruits was increased to 33,000 to accumulate the trained manpower for a field army of 180,000 men. Older men would continue to serve as garrison troops and by 1926 340,000 men would be available. Implementation of the new scheme had disrupted the old one but had not become effective by 1914. During the crisis over the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, regiments were divided and eight conscription classes were incorporated into the army to provide 117,000 men for the field army and 200,000 fortress troops. The Belgian army planned all-round defence, rather than concentrating the army against a particular threat. Belgian defences were to be based on a National Redoubt at Antwerp, with the field army massed in the centre of the country 60 km (37 mi) from the border, ready to manoeuvre to delay an invasion, while the frontiers were protected by the fortified regions of Liège and Namur.[3] The German invasion of Belgium on 4 August 1914, in violation of Article VII of the Treaty of London was the casus belli, the reason given by the British government, for declaring war on Germany.[4]

War plans

Belgian defensive plans

Belgian military planning was based on the assumption that other powers would oust an invader but the likelihood of a German invasion did not lead to France and Britain being seen as allies or for the Belgian government to do more than protect its independence. The Anglo-French Entente (1904) had led the Belgians to perceive that the British attitude to Belgium had changed and that it was now seen as a protectorate. A Belgian General Staff was formed in 1910 but the Chef d'État-Major Général de l'Armée, Lieutenant-Général Harry Jungbluth was retired on 30 June 1912 and not replaced until May 1914 by Lieutenant-General Chevalier Antonin de Selliers de Moranville. Moranville began planning for the concentration of the army and met railway officials on 29 July.[5]

Belgian troops were to be massed in central Belgium, in front of the National Redoubt at Antwerp ready to face any border, while the Fortified Position of Liège and Fortified Position of Namur were left to secure the frontiers. On mobilisation, the King became Commander-in-Chief and chose where the army was to concentrate. Amid the disruption of the new rearmament plan the disorganised and poorly trained Belgian conscripts would benefit from a central position to delay contact with an invader. The army would also need fortifications for defence but these had been built on the frontier. Another school of thought wanted a return to a frontier deployment, in line with French theories of the offensive. The Belgian plan that emerged was a compromise in which the field army concentrated behind the Gete river with two divisions forward at Liège and Namur.[5]

Germany: Schlieffen–Moltke Plan

German strategy had given priority to offensive operations against France and a defensive posture against Russia since 1891. German planning was determined by numerical inferiority, the speed of mobilisation and concentration and the effect of the vast increase of the power of modern weapons. Frontal attacks were expected to be costly and protracted, leading to limited success, particularly after the French and Russians modernised their fortifications on the frontiers with Germany. Alfred von Schlieffen, Chief of the Imperial German General Staff (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL, the German army high command) from 1891 to 1906 devised a plan to evade the French frontier fortifications, with an offensive on the northern flank, which would have a local numerical superiority and obtain rapidly a decisive victory. By 1898–1899, such a manoeuvre was intended to swiftly pass between Antwerp and Namur and threaten Paris from the north.[6]

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger succeeded Schlieffen in 1906 and was less certain that the French would conform to German assumptions. Moltke adapted the deployment and concentration plan to accommodate an attack in the centre or an enveloping attack from both flanks as variants, by adding divisions to the left flank opposite the French frontier, from the c. 1,700,000 men expected to be mobilised in the Westheer (Western Army). The main German force would still advance through Belgium and attack southwards into France, the French armies would be enveloped on the left and pressed back over the Meuse, Aisne, Somme, Oise, Marne and Seine, by short, rapid attacks, unable to withdraw into central France. The French would either be annihilated or the manoeuvre from the north would create conditions for victory in the centre or in Lorraine, on the common border.[7]

A corollary to the emphasis on the Western Front was a lack of troops for the Eastern Front against Russia. In the east the Germans planned a defensive strategy and relied on the Austro-Hungarian Army (Landstreitkräfte Österreich-Ungarns/Császári és Királyi Hadsereg) to divert the Russians from East Prussia, while France was crushed. Divisions from the German army in the west (Westheer) would be redeployed to the East to deal with the Russians as soon as a breathing-space was gained against the French.[8]

France: Plan XVII

Under Plan XVII the French peacetime army was to form five field armies, with a group of reserve divisions attached to each army and a group of reserve divisions on each flank, a military force of c. 2,000,000 men. The armies were to concentrate opposite the German frontier around Épinal, Nancy and Verdun–Mezières, with an army in reserve around Ste. Ménéhould and Commercy. Since 1871, railway building had given the French General Staff sixteen lines to the German frontier, against thirteen available to the German army and the French could afford to wait until German intentions were clear. The French deployment was intended to be ready for a German offensive in Lorraine or through Belgium. It was anticipated that the Germans would use reserve troops but also expected that a large German army would be mobilised on the border with Russia, leaving the western army with sufficient troops only to advance through Belgium south of the Meuse and Sambre rivers. French intelligence had obtained a 1905 map exercise of the German general staff, in which German troops had gone no further north than Namur and assumed that plans to besiege Belgian forts were a defensive measure against the Belgian army.[9]

A German attack from south-eastern Belgium towards Mézières and a possible offensive from Lorraine towards Verdun, Nancy and St. Dié was anticipated; the plan was an evolution from Plan XVI and made more provision for the possibility of a German offensive from the north through Belgium. The First, Second and Third armies were to concentrate between Épinal and Verdun opposite Alsace and Lorraine, the Fifth Army was to assemble from Montmédy to Sedan and Mézières and the Fourth Army was to be held back west of Verdun, ready to move east to attack the southern flank of a German invasion through Belgium or southwards against the northern flank of an attack through Lorraine. No formal provision was made for combined operations with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) but joint arrangements had been made and in 1911 during the Second Moroccan Crisis, the French had been told that six British divisions could be expected to operate around Maubeuge.[10]

Outbreak of war

On 28 June the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated and on 5 July the Kaiser promised "the full support of Germany" if Austria-Hungary took action against Serbia. On 23 July the Austro-Hungarian Government sent an ultimatum to Serbia and next day the British Foreign Minister Sir Edward Grey proposed a conference to avert a war and the Belgian Government issued a declaration that Belgium would defend its neutrality "whatever the consequences". On 25 July the Serbian Government ordered mobilisation and on 26 July, the Austro-Hungarian Government ordered partial mobilisation against Serbia. The French and Italian governments accepted British proposals for a conference on 27 July but the next day Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and the German government rejected the British proposal for a conference and on 29 July the Russian government ordered partial mobilisation against Austria-Hungary as hostilities commenced between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. The German government made proposals to secure British neutrality; the Admiralty sent a Warning Telegram to the Fleets and the War Office ordered the Precautionary Period On 30 July the British government rejected German proposals for British neutrality and next day the Austro-Hungarian and Russian governments ordered full mobilisation.[11]

At midnight on 31 July – 1 August the German government sent an ultimatum to Russia and announced a state of "Kriegsgefahr" during the day; the Turkish government ordered mobilisation and the London Stock Exchange closed. On 1 August the British government ordered the mobilisation of the Navy, the German government ordered general mobilisation and declared war on Russia. Hostilities commenced on the Polish frontier, the French government ordered general mobilisation and next day the German government sent an ultimatum to Belgium demanding passage through Belgian territory, as German troops crossed the frontier of Luxembourg. Military operations began on the French frontier, Libau was bombarded by a German cruiser SMS Augsburg and the British government guaranteed naval protection for French coasts. On 3 August the Belgian Government refused German demands and the British Government guaranteed military support to Belgium should the German army invade. Germany declared war on France, the British government ordered general mobilisation and Italy declared neutrality. On 4 August the British government sent an ultimatum to Germany and declared war on Germany at midnight on 4–5 August Central European time. Belgium severed diplomatic relations with Germany and Germany declared war on Belgium. German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked Liège.[12]

Battles

Battle of Liège, 4–16 August

The Battle of Liège was the primary engagement in the German invasion of Belgium and the first battle of World War I. The attack on the city began on 5 August and lasted until 16 August, when the last fort was surrendered. The German invasion led the British to declare war and the length of the siege may have delayed the German invasion of France by 4–5 days. Railways needed by the German armies in eastern Belgium were closed during the early part of the siege and by the morning of 17 August, the German 1st, 2nd and 3rd armies were free to resume their advance to the French frontier, yet German troops only appeared in strength before Namur on 20 August.[13] The Belgian field army withdrew from the Gete towards Antwerp from 18–20 August and Brussels was captured unopposed on 20 August. The siege of Liège had lasted for eleven days, rather than the two days anticipated by the Germans.[13]

Belgian military operations in the east of the country had delayed German plans, which some writers claimed had been advantageous to the Franco-British forces in northern France and in Belgium.[13] Wolfgang Förster wrote that the German timetable of deployment had required its armies to reach a line from Thionville to Sedan and Mons by the 22nd day of mobilisation (23 August), which was achieved ahead of schedule. In Bulletin Belge des Sciences Militaires, a four-day delay was claimed.[13] John Buchan wrote that "The triumph was moral – an advertisement to the world that the ancient faiths of country and duty could still nerve the arm for battle, and that the German idol, for all its splendour, had feet of clay".[14] In 2007, Foley called the neutralisation of the Belgian defences at Liège sufficient to enable the German right wing to squeeze through, a small bump in the road for the Germans, who had mobilised in two weeks and were ready to invade France by 20 August.[15]

Battle of Halen, 12 August 1914

The Battle of Halen (Haelen) was fought by mounted and dismounted cavalry and other forces on 12 August 1914 between German forces, led by Georg von der Marwitz and Belgian forces, led by Lieutenant-General Léon de Witte. To block a German advance towards Hasselt and Diest, the Cavalry Division commanded by de Witte, was sent to guard the bridge over the river Gete at Halen. During an evening meeting, the Belgian general staff directed de Witte to fight a dismounted action in an attempt to nullify the German numerical advantage.[16] From communication intercepts, the Belgian Headquarters discovered that the Germans were heading in force towards de Witte and sent the 4th Infantry Brigade to reinforce the Cavalry Division. The battle began around 8:00 a.m. when a German scouting party, advancing from Herk-de-Stad, was engaged with small-arms fire by Belgian troops. About 200 Belgian soldiers attempted to set up a fortified position in the old brewery in Halen but were driven out of the building when the Germans brought up field artillery.[16]

Belgian engineers had blown the bridge over the Gete but the structure only partly collapsed, which left the Germans an opportunity to send about 1,000 troops into the centre of Halen.[16] The main Belgian defence line was to the west of Halen, on terrain which was partially overlooked by the Germans. The relatively easy capture of Halen made the Germans confident and led to several ill-conceived attempts to capture the Belgian position with sabre and lance attacks. Towards the end of the day the Germans were forced to retire towards their main columns east of Halen.[17] The battle was a victory for the Belgian army but was strategically indecisive. The Germans went on to besiege the fortified cities of Namur, Liège and Antwerp, which had formed the basis of the Belgian defensive system, intended to delay an invader until foreign troops could intervene, according to the Treaty of London. The Germans suffered casualties of 150 dead, 600 wounded, 200–300 prisoners and c. 400 horses. Belgian casualties were 160 dead and 320 wounded.[18]

Siege of Namur, 20–24 August

Namur was defended by a ring of modern fortresses, known as the Fortified Position of Namur (Position fortifiée de Namur) and guarded by the Belgian 4th Division. When the siege began on 20 August, the Germans reversed the tactics used at Liège, by waiting until the siege train arrived from Liège and bombarding the forts before attacking with infantry. French troops sent to relieve the city were defeated at the Battle of Charleroi and only a few managed to participate in the fighting for Namur. The forts were destroyed in the bombardment, much of the Belgian 4th Division withdrew to the south and the Belgian fortress troops were forced to surrender on 24 August. The Belgians had held the German advance for several days longer than the Germans had anticipated, which allowed Belgium and France more time to mobilise.[19] The Belgian army had c. 15,000 casualties of whom c. 10,000 were from the 4th Division, which was moved to Le Havre and then by sea to Ostend on 27 August, from where it re-joined the field army at Antwerp.[20] The authors of Der Weltkrieg, the German official history recorded the taking of 6,700 Belgian and French prisoners, the capture of twelve field guns and 900 casualties, of whom c. 300 were killed.[21]

Battles of Charleroi and Mons, 21–23 August

The Battle of Charleroi was fought on 21 August 1914, between French and German forces and was part of the Battle of the Frontiers. The French were planning an attack across the river Sambre, when the Germans attacked and the French Fifth army was forced into a retreat, which prevented the German army from enveloping and destroying the French. After another defensive action in the Battle of St. Quentin, the French were pushed to within miles of Paris. The British attempted to hold the line of the Mons–Condé Canal on the left flank of the French Fifth army against the German 1st Army and inflicted disproportionate casualties, before retreating when some units were overrun and the French Fifth Army on the right flank withdrew in the aftermath of the battle further east at Charleroi. Both sides had tactical success at Mons, the British had withstood the German First Army for 48 hours, prevented the French Fifth Army from being outflanked and then retired in good order. For the Germans the battle had been a tactical defeat and a strategic success. The First Army had been delayed and suffered many casualties but had forced the crossing of the Mons–Condé Canal and begun to advance into France.[22]

Siege of Antwerp, 28 September – 10 October

At the fortified city of Antwerp, German troops besieged a garrison of Belgian fortress troops, the Belgian field army and the British Royal Naval Division. The city was ringed by forts, known as the National Redoubt and was invested to the south and east by German forces, which began a bombardment of the Belgian fortifications with heavy and super-heavy artillery on 28 September. The Belgian garrison had no hope of victory without relief and despite the arrival of the Royal Naval Division beginning on 3 October the Germans penetrated the outer ring of forts. The German advance began to compress a corridor from the west of the city along the Dutch border to the coast. The Belgians at Antwerp had used the strip to maintain contact with the rest of unoccupied Belgium and the Belgian field army commenced a withdrawal westwards towards the coast.[23]

On 9 October, the remaining garrison surrendered, the Germans occupied the city and some British and Belgian troops escaped north to the Netherlands, where they were interned for the duration of the war. A large amount of ammunition and many of the 2,500 guns at Antwerp were captured intact by the Germans.[23] The c. 80,000 surviving men of the Belgian field army escaped westwards, with most of the Royal Naval Division.[24] British casualties were 57 killed, 138 wounded, 1,479 interned and 936 taken prisoner. The operations to save Antwerp failed but detained German troops when they were needed for operations against Ypres and the coast. Ostend and Zeebrugge were captured by the Germans unopposed and the troops from Antwerp advanced to positions along the Yser river and fought in the Battle of the Yser, which thwarted the final German attempt to turn the Allied northern flank.[25]

Peripheral operations, August–October

Belgian resistance and German fear of Francs-tireurs, led the Germans to implement a policy of schrecklichkeit (frightfulness) against Belgian civilians soon after the invasion, in which massacres, executions, hostage taking and the burning of towns and villages took place and became known as the Rape of Belgium.[26] After the Battle of the Sambre the French Fifth Army and the BEF retreated and on 25 August, General Fournier was ordered to defend the fortress, which was surrounded on 27 August by the VII Reserve Corps, which had two divisions and eventually received some of the German super-heavy artillery, brought from the sieges in Belgium. Maubeuge was defended by fourteen forts, with a garrison of 30,000 French Territorials and c. 10,000 French, British and Belgian stragglers and blocked the main Cologne–Paris rail line. Only the line from Trier to Liege, Brussels, Valenciennes and Cambrai was open and had to carry supplies southward to the armies on the Aisne and transport troops of the 6th Army northwards.[27]

On 29 August the Germans began a bombardment of the forts around Maubeuge. On 5 September, four of the forts were stormed by German infantry, creating a gap in the defences. On 7 September the garrison surrendered. The Germans took 40,000 prisoners and captured 377 guns.[28] After the capture of Maubeuge the line from Cologne–Paris line was of limited use between Diedenhofen and Luxembourg, until the bridge at Namur was repaired.[27] The Battle of the Marne began as the Maubeuge forts were stormed and during the Battle of the Aisne one of the VII Reserve Corps divisions arrived in time to join the German 7th Army, which closed a dangerous gap in the German line.[28] While the BEF and the French armies conducted the Great Retreat into France (24 August – 28 September), small detachments of the Belgian, French and British armies conducted operations against German cavalry and Jäger.[29]

On 27 August, a squadron of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) had flown to Ostend, for air reconnaissance sorties between Bruges, Ghent and Ypres.[30] British marines landed at Dunkirk on the night of 19/20 September and on 28 September a battalion occupied Lille. The rest of the brigade occupied Cassel on 30 September and scouted the country in motor cars; an RNAS Armoured Car Section was created, by fitting vehicles with bullet-proof steel.[31][32] On 2 October, the Marine Brigade was moved to Antwerp, followed by the rest of the Naval Division on 6 October, having landed at Dunkirk on the night of 4/5 October. From 6–7 October, the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division landed at Zeebrugge.[33] Naval forces collected at Dover were formed into a separate unit, which became the Dover Patrol, to operate in the Channel and off the French-Belgian coast.[34]

Eastern Front (September–October)

On 3 September Lemberg was captured by the Russian army and the Battle of Rawa (Battle of Tarnavka 7–9 September) began in Galicia. The First Battle of the Masurian Lakes (7–14 September) began and on 8 September the Austro-Hungarian army commenced the Second Invasion of Serbia, leading to the Battle of Drina (6 September – 4 October). The Second Battle of Lemberg (8–11 September) began and on 11 September, Austrian forces in Galicia retreated. The Battle of the Masurian Lakes ended on 15 September and Czernowitz in Bukovina was taken by the Russian army. On 17 September Serbian forces in Syrmia were withdrawn and Semlin evacuated, as the Battle of the Drina ended. Next day General Paul von Hindenburg was appointed Oberbefehlshaber der gesamten Deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten (Ober Ost, Commander-in-Chief of German Armies in the Eastern Theatre).[35][a]

Race to the Sea, 17 September – 19 October

The Race to the Sea took place from about 17 September – 19 October 1914, after the Battle of the Frontiers (7 August–13 September) and the German advance into France, which had been stopped at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September) and was followed by the First Battle of the Aisne (13 September – 28 September), a Franco-British counter-offensive.[b] The term described reciprocal attempts by the Franco-British and German armies, to envelop the northern flank of the opposing army through Picardy, Artois and Flanders, rather than an attempt to advance northwards to the sea. Troops were moved from the French-German border by both sides, to the western flank to prevent opposing outflanking moves and then to counter-outflank the opponent. At the battles of Picardy and Albert in late September, the French Second and German 6th armies fought meeting engagements from the Oise north to the Somme but neither was able to envelop the northern flank of the opponent.[44]

French and German armies were moved from the east for further outflanking attempts to the north and the BEF made a camouflaged move from the Aisne front on the night of 1/2 October, with no movement by day, which with rainy weather grounding aircraft, deceived the Germans. On 8–9 October the BEF began to assemble around Abbeville, ready to begin an offensive around the German northern flank, towards the Belgian and Allied troops in Flanders. French and German efforts to outflank each other were frustrated, during the Battle of Arras in early October and the battles of La Bassée, Armentières and Messines. The "race" ended on the North Sea coast of Belgium around 19 October, when the last open area from Diksmuide to the North Sea was occupied by Belgian troops, who had been withdrawn from the siege of Antwerp (28 September – 10 October). The British held a line from La Bassée to Passchendaele, the French from Passchendaele to Diksmuide and the Belgian army from Diksmuide to Nieuwpoort. The outflanking attempts had resulted in a number of encounter battles but neither side was able to gain a decisive victory.[44]

Battle of the Yser, 16 October – 2 November

The Battle of the Yser took place in October 1914 along a 35 km (22 mi) long stretch of the Yser river and Yperlee canal in Belgium.[45] On 15 October c. 50,000 Belgian troops ended their retreat from Antwerp and took post between Nieuwpoort and French Fusiliers Marins at Diksmuide, which marked the end of the "Race to the Sea". Both sides conducted offensives and when the attacks by the Tenth Army and the BEF to Lille was defeated in early October, more French troops were sent to the north and formed the Détachement d'Armée de Belgique ("Army Detachment of Belgium") under the command of General Victor d'Urbal.[46] Falkenhayn assembled a new 4th Army from the III Reserve Corps, available since the fall of Antwerp and four new reserve corps, which had been raised in Germany in August and were deficient in training, weapons, equipment and leadership. The 4th Army offensive along the coast to St. Omer, began with operations against the Belgians, to drive them back from the Yser.[47]

On 16 October King Albert ordered that retreating soldiers were to be shot and officers who shirked would be court-martialled. The Belgian army was exhausted, water was so close to the land surface that trenches could only be dug 1–2 ft (0.30–0.61 m) deep and the field artillery was short of ammunition and had worn guns. A German offensive began on 18 October and by 22 October had gained a foothold across the Yser at Tervaete. By the end of 23 October the Belgians had been driven back from the riverbank and next day the Germans had a bridgehead 5 km (3.1 mi) wide. The French 42nd Division was used to reinforce the Belgians who had fallen back to a railway embankment from Diksmuide to Nieuwpoort which was 3.3–6.6 ft (1–2 m) above sea level. By 26 October the position of the Belgian army had deteriorated to the point that another withdrawal was contemplated. King Albert rejected withdrawal and next day sluice gates at Nieuwpoort were opened to begin the flooding of the coastal plain. A German attack on 30 October crossed the embankment at Ramscappelle but was forced back during a counter-attack late on 31 October and on 2 November Diksmuide was captured.[48]

First Battle of Ypres, 19 October – 22 November

The First Battle of Ypres (part of the First Battle of Flanders) began on 19 October with attacks by the German 6th and 4th armies at the same time that the BEF attacked towards Menin and Roulers. On 21 October, attacks by the 4th Army reserve corps were repulsed in a costly battle and on 23–24 October German attacks were conducted to the north, on the Yser by the 4th Army and to the south by the 6th Army. French attacks by the new Eighth Army were made towards Roulers and Thourout, which diverted German troops from British and Belgian positions. A new German attack was planned in which the 4th and 6th armies would pin Allied troops while a new formation, Armeegruppe von Fabeck with six new divisions and more than 250 heavy guns took over the boundary of the two German armies, to attack north-west between Messines and Gheluvelt.[49]

The British I Corps was dug in astride the Menin road, with dismounted British cavalry further south. German attacks took ground on the Menin road on 29 October and drove back the British cavalry next day, from Zandvoorde and Hollebeke to a line 3 km (1.9 mi) from Ypres.[49] Three French battalions released from the Yser front by the inundation of the ground around the Yser, were sent south and on 31 October the British defence of Gheluvelt began to collapse, until a battalion counter-attacked and drove back the German troops from the crossroads.[49] German attacks south of the Menin road took small areas but Messines ridge had been consolidated by the British garrison and was not captured. By 1 November, the BEF was close to exhaustion and 75 of 84 infantry battalions had fewer than 300 men left; 1⁄3 of their establishment.[49]

The French XIV Corps was moved north from the Tenth Army and the French IX Corps attacked southwards towards Becelaere, which relieved the pressure on both British flanks. German attacks began to diminish on 3 November, by when Armeegruppe von Fabeck had lost 17,250 casualties. A French offensive was planned for 6 November towards Langemarck and Messines, to widen the Ypres salient but German attacks began again on 5 November in the same area until 8 November, then again on 10–11 November. The main attack on 10 November was made by the 4th Army between Langemarck and Diksmuide, in which Diksmuide was lost by the Franco-Belgian garrison. Next day to the south, the British were subjected to an unprecedented bombardment between Messines and Polygon Wood and then an attack by Prussian Guard, which broke into British positions along the Menin road, before being forced back by counter-attacks.[50] From mid-October to early November the German Fourth Army lost 52,000 and the Sixth Army lost 28,000 casualties.[51]

Atrocities

After the defeat of the Imperial forces of Napoleon III in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), c. 58,000 irregular troops known as francs tireurs (free shooters) were established by the French Government of National Defence, which killed c. 1,000 German troops and diverted c. 120,000 troops from field operations to guard the lines of communication. [52] The status of neutral countries was established by the Fifth Convention of the Hague Peace Conference (1907) and signed by Germany. The Belgian government did not forbid resistance, because belligerents were not allowed to move troops or supplies through neutral territory; Article 5 required neutrals to prevent such acts and Article 10 provided that resistance by a neutral could not be considered to be hostile. At Hervé during the night of 4 August, firing broke out and a few days later a German reporter wrote that only nineteen of 500 houses were still standing.[26] The speed by which allegations of franc tireur warfare reached Germany led to suspicions of orchestration, since newspapers reported atrocities against German soldiers as soon as 5 August; on 8 August, troops marching towards the German-Belgian frontier bought newspapers containing lurid details of Belgian civilians marauding, ambushing German troops, desecrating corpses and poisoning wells.[26]

To avoid delays and minimise the detachments of garrisons to guard lines of communication, the German army resorted to schrecklichkeit (frightfulness), quickly to terrorise civilians into submission. On some occasions, the atrocities were committed by front-line troops in the heat of the moment; other crimes were cold blooded, taking place days after the fighting had ended. Andenne near Namur, was burnt down on 20 August and a German proclamation claimed that 110 people had been shot, with a Belgian account claiming 211 dead. At Seilles, fifty people were killed and at Tamines 384 civilians were shot. Dutch civilians heard gunfire on the night of 23 August, from Visé over the border and in the morning 4,000 refugees crossed the frontier, describing killings and the abduction of 700 men and boys for forced labour in Germany. Ten hostages were taken from every street in Namur and in other places one from every house.[53] At Dinant the French fell back on 22 August and blew the bridge; German troops repairing the crossing were ostensibly obstructed by civilians, which was allegedly witnessed by General Max von Hausen, the 3rd Army commander. Hundreds of hostages were taken and lined up in the town square that evening and shot, 612 men, women and children being killed, after which the town centre was looted and burned.[53] Horne and Kramer calculated that 670 civilians were killed in the town.[54]

The 1st Army passed through Leuven (Louvain) on 19 August and was followed by the IX Reserve Corps. On 25 August, a Belgian sortie from Antwerp drove back German outposts and caused confusion behind the front line. A horse entered Leuven during the night and caused a stampede, which panicked German sentries, after which General von Luttwitz, the Military Governor of Brussels, ordered reprisals. Burning and shooting by German troops took place for five days, during which 248 residents were killed; the surviving population of 10,000 people were expelled and over 2,000 buildings were burnt down. At the Catholic University of Leuven, the historic library of 300,000 medieval books and manuscripts was destroyed. Large amounts of strategic materials, foodstuffs and modern industrial equipment were looted and transferred to Germany.[55][56] From 5 August to 21 October, German troops burned homes and killed civilians throughout eastern and central Belgium, including crimes at Aarschot (156 dead), Mechelen, Dendermonde and from Berneau in Liège Province to Esen in the province of West Flanders.[57]

In 2007, Terence Zuber called writing on German atrocities by Schmitz and Niewland (1924), Horne and Kramer (2001) and Zuckerman (2004) apologia and wrote that on 5 August, the Belgian government armed 100,000 civilians as "inactive Garde Civique", who joined the 46,000 members of the active Garde Civique. Zuber called the inactive members untrained, non-uniformed and the active members little better. Zuber wrote that as no records exist, there is no evidence that the Garde Civique was trained, had officers or a chain of command and that it was a guerilla army at best. Zuber wrote that on 18 August, the Belgian government disbanded the Garde Civique but Horne and Kramer had failed to explain the disposal of 146,000 firearms and claimed that none of the former Garde Civique fired them at German soldiers. Zuber quoted a folk tradition, which had it that a civilian killed a German officer at Bellefontaine and wrote that the Germans shot Belgian civilians in reprisal for franc tireur attacks and that "franc tireur attacks" had taken place, both being war crimes. Zuber also wrote that there were no German reprisals in the Flemish areas of Belgium or the interior of France, where no franc tireur attacks occurred.[58]

Aftermath

The offensive strategies of France and Germany had failed by November 1914, leaving most of Belgium under German occupation and Allied blockade.[51] The German General Government of Belgium (Kaiserliches Deutsches Generalgouvernement Belgien), was established on 26 August 1914 with Field Marshal Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz as the Military Governor. Goltz was succeeded by General Moritz von Bissing on 27 November 1914.[59] Soon after Bissing's appointment, OHL divided Belgium into three zones. The largest of the zones was the General Governorate of Brussels and the hinterland, the second zone came under the 4th Army and included Ghent and Antwerp; the third zone, under the Kaiserliche Marine (German Navy), covered the Belgian coast. The German occupation authorities ruled Belgium under the pre-war Belgian administrative system, overseen by a small group of German officers and officials.[60]

The Germans had used Belgium to invade northern France, which had led to the Franco-British defeats of Charleroi and Mons, followed by a rapid retreat to the Marne, where the German advance was stopped. Attempts by both sides to envelop the opponent's northern flank had then brought the main armies back to the north. Sieges and small operations were being conducted by detachments from the main German armies against Belgian, British and French troops. The siege of Antwerp ended as operations resumed on the western border, with the costly and indecisive battles of the Yser and Ypres. Falkenhayn attempted to gain a limited success after the failure of the October offensive and aimed to capture Ypres and Mt Kemmel but even this proved beyond the capacity of the 4th and 6th armies. On 10 November Falkenhayn told the Kaiser that no great success could be expected on the Western Front. German troops were tired and there was little heavy artillery ammunition left. The Westheer was ordered to dig in and defend its conquests, while the deteriorating situation on the Eastern Front was retrieved.[61]

Notes

- ^ On 21 September, Jaroslaw in Galicia was taken by the Russian army. On 24 September Przemyśl was isolated by Russian forces, beginning the First Siege as Russian forces conducted the First Invasion of North Hungary (24 September – 8 October). Military operations began on the Niemen (25–29 September) but German attacks were suspended on 29 September. The retreat of Austro-Hungarian forces in Galicia ended and Maramaros-Sziget was captured by the Russian army. An Austro-Hungarian counter-offensive began in Galicia on 4 October and Maramaros-Sziget was retaken. On 9 October, the First German offensive against Warsaw began with the battles of Warsaw (9–19 October) and Ivangorod (9–20 October).[35]

- ^ Writers and historians have criticised the term Race to the Sea and used several date ranges, for the period of mutual attempts to outflank the opposing armies on their northern flanks. In 1925, Edmonds the British Official Historian, used dates of 15 September – 15 October and in 1926 17 September – 19 October.[36][37] In 1929 the fifth volume of Der Weltkrieg the German Official History, described the progress of German outflanking attempts, without labelling them.[38] In 2001 Strachan used 15 September – 17 October.[39] In 2003 Clayton gave dates from 17 September – 7 October.[40] In 2005, Doughty used the period from 17 September – 17 October and Foley from 17 September to a period between 10–21 October.[41][42] In 2010 Sheldon placed the beginning of the "erroneously named" race from the end of the Battle of the Marne to the beginning of the Battle of the Yser.[43]

Footnotes

- ^ Albertini 2005, p. 414.

- ^ a b Strachan 2003, p. 208.

- ^ a b Strachan 2003, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Albertini 2005, p. 504.

- ^ a b Strachan 2003, pp. 209–211.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 66, 69.

- ^ Strachan 2003, pp. 190, 172–173, 178.

- ^ Strachan 2010, p. 35.

- ^ Strachan 2003, p. 194.

- ^ Strachan 2003, pp. 195–198.

- ^ Skinner & Stacke 1922, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Skinner & Stacke 1922, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Edmonds 1926, p. 33.

- ^ Buchan 1921, p. 134.

- ^ Foley 2007, p. 83.

- ^ a b c General Staff 1915, p. 19.

- ^ General Staff 1915, pp. 20–21.

- ^ General Staff 1915, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Donnell 2007, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Tyng 2007, p. 100.

- ^ Reichsarchiv 1925, p. 416.

- ^ Baldwin 1963, p. 25.

- ^ a b Strachan 2003, p. 1,032.

- ^ Sheldon 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c Terraine 1992, p. 25.

- ^ a b Strachan 2003, pp. 241, 266.

- ^ a b Rickard 2007.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 39–65.

- ^ Raleigh 1969, pp. 371–374.

- ^ Raleigh 1969, pp. 375–390.

- ^ Corbett 2009, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, p. 405.

- ^ Corbett 2009, pp. 170–202.

- ^ a b Skinner & Stacke 1922, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 27–100.

- ^ Edmonds 1926, pp. 400–408.

- ^ Reichsarchiv 1929, p. 14.

- ^ Strachan 2003, pp. 266–273.

- ^ Clayton 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p. 98.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Sheldon 2010, p. x.

- ^ a b Strachan 2003, pp. 264–274.

- ^ Barton, Doyle & Vandewalle 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Strachan 2003, pp. 273, 274–275.

- ^ Strachan 2003, pp. 275–276.

- ^ a b c d Strachan 2003, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Strachan 2003, pp. 277–278.

- ^ a b Foley 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Terraine 1992, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Terraine 1992, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Horne & Kramer 1994, pp. 1–33.

- ^ Terraine 1992, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Commission 1915, pp. 679–704, 605–615.

- ^ Horne & Kramer 1994, pp. 1–24, App I.

- ^ Zuber 2009, pp. 285–287.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 9.

- ^ Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 209.

- ^ Foley 2007, pp. 103–104.

References

Books

- Albertini, L. (2005) [1952]. The Origins of the War of 1914. Vol. III (repr. ed.). New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-33-9.

- Baldwin, H. (1963). World War I: An Outline History. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 464551794.

- Barton, P.; Doyle, P; Vandewalle, J. (2005). Beneath Flanders Fields: the Tunnellers' War, 1914–1918. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 978-0-7735-2949-6.

- Buchan, J. (1921). A History of the Great War. Edinburgh: Nelson. OCLC 4083249.

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory: The French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35949-3.

- Corbett, J. S. (2009) [1938]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (2nd, Naval & Military Press repr. ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 978-1-84342-489-5. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Der Herbst-Feldzug 1914: Im Westen bis zum Stellungskrieg, im Osten bis zum Rückzug [The Autumn Campaign in 1914 in the West to the beginning of Trench Warfare, in the east to the Retreat]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918 Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Vol. V (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler & Sohn. 1929. OCLC 838299944. Retrieved 5 February 2014 – via Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek.

- Die Grenzschlachten im Westen [The Frontier Battles in the West]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918 Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Vol. I (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. 1925. OCLC 163368678. Retrieved 29 January 2014 – via Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek.

- Donnell, C. (2007). The Forts of the Meuse in World War I. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-114-4.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916 (pbk. ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg: 1914 The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne. Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. I. Part 1. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). "Foreword, Hew Strachan". Germany's Western Front, 1915: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. II. Waterloo Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

- Strachan, H. Foreword. In Humphries & Maker (2010).

- Official Commission of the Belgian Government: Reports on the Violation of the Rights of Nations and of the Laws and Customs of War in Belgium. London: HMSO. 1915. OCLC 820928791. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Raleigh, W. A. (1969) [1922]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. Vol. I (Hamish Hamilton ed.). Oxford: OUP. OCLC 785856329. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Strachan, H. (2003) [2001]. The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Terraine, J. (1992) [1980]. The Smoke and the Fire: Myths and Anti-Myths of War, 1861–1945 (Leo Cooper ed.). London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-85052-330-0.

- The war of 1914 Military Operations of Belgium in Defence of the Country and to Uphold Her Neutrality. London: W. H. & L Collingridge. 1915. OCLC 8651831. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Thomas, N. (2003). The German Army in World War I, 1914–15. Vol. I. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-565-5.

- Tucker, S.; Roberts, P. M. (2005). World War I: Encyclopedia. Vol. I. New York: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme ed.). New York: Longmans, Green and Co. ISBN 978-1-59416-042-4.

- Zuber, T. (2009) [2007]. The Battle of the Frontiers: Ardennes 1914 (History Press pbk. ed.). Charleston SC: History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5255-5.

Journals

- Horne, J.; Kramer, A. (1994). "German "Atrocities" and Franco-German Opinion, 1914: The Evidence of German Soldiers' Diaries". Journal of Modern History. 66 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1086/244776. ISSN 0022-2801.

Websites

- Rickard, J. (1 September 2007). "Siege of Maubeuge, 25 August – 7 September 1914". Retrieved 18 February 2014.

Further reading

- Erdmann, K. D., ed. (1972). Kurt Riezler: Tagebücher, Aufsätze, Dokumente [Kurt Riezler: Diaries, Essays, Documents]. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. OCLC 185654196.

- Horne, John N.; Kramer, Alan (2001). German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial. Newhaven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08975-2.

- Kluck, A. (1920). The March on Paris and the Battle of the Marne, 1914. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 2513009. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Zuckerman, L. (2004). The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9704-4.

External links

- Conflicts in 1914

- 1914 in Belgium

- 1914 in France

- Sieges involving Germany

- Race to the Sea

- Western Front (World War I)

- Battles of World War I involving Belgium

- Battles of World War I involving British India

- Military operations of World War I involving Germany

- Military operations of World War I involving the United Kingdom

- Military operations of World War I involving France

- Military operations of World War I involving Austria-Hungary

- Invasions of Belgium

- Invasions by Germany

- World War I invasions

- Belgium–Germany military relations