Denial of genocides of Indigenous peoples

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Denial of atrocities against Indigenous Peoples are present or historical claims made by organizations or states that deny any of various atrocities against Indigenous Peoples when academic consensus or present state policy that acknowledges that such crimes occurred.[1] This includes denial of various genocides against Indigenous Peoples and other crimes against humanity, war crimes, or ethnic cleansing.[2][3][4] Denial may be the result of minority status, cultural distance, small scale or visibility, marginalization, the lack of political, economic and social status of indigenous nations within a modern nation-state.[5][6][7][8]

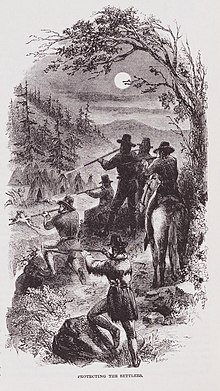

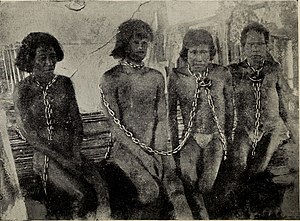

During the age of colonization, several states colonized territories which were inhabited by Indigenous Peoples, and in some cases, they created new states that included the surviving Indigenous Peoples within their new borders.[9][10][11] In such processes of expanding their frontier, there were a number of cases of alleged atrocity crimes against Indigenous nations. Given that the dominant or majority group have held political and economic power, they have not addressed these issues on some occasions.[12][13][14][6] Scholars and historians have increasingly examined the impact of settler colonialism and internal colonialism in general from the perspective of Indigenous Peoples.[15][16][17][18][19][6][20] The forced population and territorial controls of Indigenous Peoples may include internal displacement, forced containment in reservations, forced assimilation and criminalization.[21]

| Part of a series on |

| Denial of mass killings |

|---|

| Instances of denial |

|

| Scholarly controversy over mass killings |

| Related topics |

Background

In comparison with the legal definition of genocide in the Genocide Convention that has been used in actual litigation,[22] additional scholarly definitions have been used to examine the diverse history of genocide. For example, genocide scholar Israel Charny has proposed a definition of genocide: “Genocide in the generic sense is the mass killing of substantial numbers of human beings, when not in the course of military action against the military forces of an avowed enemy, under conditions of the essential defenselessness and helplessness of the victims.”[23]

According to Gregory Stanton, founder of Genocide Watch, who wrote about the ten stages of genocide, the final stage of a genocide process is denial. In this stage, the perpetrators minimize, negate, lie or conceal information about events. Victims are blamed and deaths are attributed to side factors such as disease or starvation.[24] Ward Churchill explains denial of genocide in terms of the politics of genocide recognition.[18] Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky have argued that the attention given to issues is the product of mass media, as they mention in Manufacturing Consent: “A propaganda system will consistently portray people abused in enemy states as worthy victims, whereas those treated with equal or greater severity by its own government or clients will be unworthy!"[25] Thus, Chomsky views the term genocide as one that is used by those in positions of political power and media prominence against their rivals, but the avoidance of using the term to describe their own actions, past and present.[26]

Human rights and genocide are issues of international concern as the alleged perpetrators can be state agents themselves, while some states argue that internal matters are an issue of sovereignty.[27] Hitchcock and Twedt say that even though many countries have committed genocide, many times other countries and even the UN avoid criticizing their internal affairs.[27]

Unfortunately, many states do not respect the rights or even the lives of Indigenous Peoples which exist within their political borders.[28] These borders themselves do not predate the communal territories of Indigenous Peoples and may be the result of a settler or exploitation colonization process. For example, Britain and France traced close to 40% of the entire length of today's international boundaries.[29] In the latter part of the twentieth century the genocide of Indigenous Peoples attracted more attention from the international community including scholars and human rights organizations.[30]

Indigenous Peoples (also known as First Peoples, First Nations, Aboriginal Peoples, Native Peoples, Indigenous Natives, or Autochthonous Peoples) are the earliest known inhabitants of a territory, especially a territory that has been colonized by a now-dominant group.[31] Ninety of the world's nation-states contain people that self-identify as Indigenous. This fact and the age of colonization gave rise to many instances of atrocities perpetrated on both sides as settlers expanded.[1] Self-identification is a core concept in the definition of Indigenous Peoples. Article 33 (1) of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) also refers to the self-identifcation of Indigenous Peoples: “Indigenous Peoples have the right to determine their own identity or membership in accordance with their customs and traditions.”[32]

Some of the main reasons for denying genocide are to evade moral responsibility, avoiding retribution, restitution and compensation, and to protect the perpetrators' reputation.[1]

Atrocity acknowledgement

Some governments have acknowledged past atrocities or apologized for the policies of previous governments.[33] This has been the case in Australia,[34][35] Belgium,[36][37][38][39][40] Britain,[41] Canada,[35][42][43] California,[44] Chile,[35] El Salvador,[35] Germany,[45] Guatemala,[46] Mexico,[47] Netherlands,[48] New Zealand,[35][49] and United States.[35][50][51][52] In their apologies, state officials do not always agree with human rights organizations' and scholars' characterization of the atrocities.[53][54]

Pope Francis apologized for the Catholic Church's role in colonization and for "crimes committed against the native peoples during the so-called conquest of America".[55] He has also apologized for the Church's role in the operation of residential schools in Canada,[56] qualifying it as genocide.[57] In 2023, the Vatican rejected the Doctrine of Discovery, which formed the basis of land appropriation by others.[58]

In 2022 Justin Welby, the Primate of the Church of England, apologized to the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, adding to similar apologies by other churches in Canada such as the Anglican Church of Canada.[59][60]

Atrocity rationalisation

As per Gregory Stanton, in the last stage of genocide, victims may be blamed for what happened to them. In the fourth phase, they can be dehumanized with hate speech.[24] In many cases, members of Indigenous communities have been described by the dominant society with negative stereotypes for generations.[27]

Often times, Indigenous Peoples have been described with accounts of generalized practices like cannibalism.[61][62][63][64] Historian David Stannard writes: "...the conquering Europeans were purposefully and systematically dehumanizing the people they were exterminating".[65] Indigenous Peoples have been dehumanized in accounts of Western scholars such as Juan Gines de Sepulveda to justify their slavery, oppression and even extermination. Controversial accounts of these peoples circulated in Europe in translations of letters by Christopher Columbus.[66] Sepulveda used references to the Bible and Aristotle to depict Native Americans as natural slaves.[67]

Australian Professor Henry Reynolds says that many genocide scholars have named Tasmania in their lists of legitimate case studies. He claims that Jews were targeted "because they were not human, just as the Tasmanian Aborigines were hunted to death for the same reason".[68]

Genocide scholar Adam Jones proposed a framework for genocide denial that consists of several strategies, including minimizing fatalities, blaming fatalities on unrelated "natural" causes, denying intent to destroy a group, and claiming self-defense in preemptive or disproportionate attacks.[9] The vectors of death raised by forced labor, displacement, slavery, overcrowded housing and schools, famine and epidemics are downplayed.[69][70] According to Australian historian Colin Tatz, denialism takes several forms: First, the denial of any past genocidal behavior. Second, the counterview that westerners have been the victims. Third, that in reality there has been more good than bad in race relations.[71]

Denial examples

According to Professor Robert K. Hitchcock, Indigenous Peoples have experienced to human rights violations, massacres, and genocides in many countries in which they reside. He said that: "the destruction of Indigenous Peoples and their cultures has been a policy of many of the world’s governments, although most government spokespersons argue that the disappearance or disruption of indigenous societies was not purposeful but rather occurred inadvertently."[72]

Leo Kuper has described denial as a routine defense: "One of the consequences of the adoption of the Genocide Convention is that denial has become a routine defense. This is intimately related to its present recognition as an international crime with potentially significant sanctions by way of punishment, claims for reparation, and restitution of territorial rights...Denial by the oblivion of indifference has also been the fate of many hunting and gathering groups and other Indigenous Peoples."[73]

Americas

Historian Howard Zinn claimed that in American history textbooks, America's history of abuse against Indigenous Peoples is mostly ignored, or presented from the point of view of the state.[74] In his 2003 work, Professor Elazar Barkan claimed that Indigenous genocide has not been given a place in the dominant version of history, particularly in the history of the United States: "Only wide recognition of indigenous destruction as genocide will acknowledge such opinion as denial. At present , these are more likely uninformed opinions."[75]

Adam Jones said that there is a denialist position on genocide of Indigenous Peoples in the informed sectors of the whole of the Americas. For example, Professor Alexander Bielakowski of the University of Findlay said that “if [it] was the plan” to “wipe out the American Indians … the US did a damn poor job following through with it.” British historian Michael Burleigh questions the disappearance of Indigenous Peoples since they are running multi-million dollar casinos.[9]

David Stannard wrote on the 500 anniversary (1992) of the beginning of colonization of the Americas about denial of atrocities: "Expressions of horror and condemnation over ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Herzegovina routinely appear on the same newspaper page or television news show as reports of the latest festivities surrounding the Columbian quincentennial. Bosnians and Croatians are worthy victims. The native peoples of the Americas never have been. But of late, American and European denials of culpability for the most thoroughgoing genocide in the history of the world have assumed a new guise."[76] Stannard also interpreted an essay[77] by author Christopher Hitchens, saying that Hitchens was supporting social Darwinism.[78]

Stannard offers the hypothetical scenario of 1940s Germans making similar statements if they had talked in such a way about Jews after World War II (as Hitchens and others talk about Native Americans) to compare the preponderance of the Holocaust vis-a-vis Native American genocide.[79] Stannard in his essay concludes that the Holocaust has gained a prominent position in the public eye, gathering the attention of the international community, but even though he recognizes the scale and tragedy of the atrocity, he warns the West to not ignore the atrocities in the Western hemisphere.[80]

According to the New York Times, Lynne V. Cheney, former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a group of scholars had a dispute over Mrs. Cheney's rejection of a television project celebrating the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's discovery of the New World. Mrs. Cheney said the proposal's use of the word "genocide" in connection with Columbus was a problem: "We might be interested in funding a film that debated that issue," she said, "but we are not about to fund a film that asserts it. Columbus was guilty of many sins, but he was not Hitler."[81]

According to a 2016-2018 survey, "only 36% of Americans almost certainly believe that the United States is guilty of committing genocide against Native Americans.” Indigenous author Michelle A. Stanley writes that "Indigenous genocide is largely denied, erased, relegated to the distant past, or presented as inevitable". She writes that Indigenous genocide is depicted broadly, without touching on the pattern of a series of separate genocides against multiple distinct tribal nations.[82] The inevitability of genocide displaces agency from people to exogenic forces such as "providence, fate and nature". This posture seeks to absolve perpetrators from responsibility of the destruction of Indigenous nations.

Academic Susan Cameron wrote: "Today, textbooks throughout the country continue to ignore or minimize the brutal treatment of Native peoples, the mass killings and persecutions, the displacement, and the continued struggles in tribal communities".[83]

Academic Ward Churchill argues that the Indigenous populations were subjected to a systematic campaign of extermination by settler colonialism in what is now known as the United States. He discusses American policies such as the Indian Removal Act and the forced assimilation of Indigenous children in American Indian boarding schools operating in the mid-1800s to early 1900s.[18] The United States ratified the Genocide Convention forty years later until 1986,[84] and did so with conditions.[85] He has called manifest destiny an ideology used to justify dispossession and genocide against Native Americans, and compared it to Lebensraum ideology of Nazi Germany.[86]

In Paraguay and Brazil, genocide scholar Leo Kuper says that genocide has been denied on the basis of alleged lack of intent to destroy.[87] The case of the Ache in Paraguay has been legally determined to be a case of political persecution, not genocide as per David Stannard.[88]

In Guatemala there has been debate over accusations of genocide, and instead calling the conflict civil war in the case of Guatemala, even though the Guatemalan Truth Commission has reported genocide.[89]

California

Benjamin Madley has described the atrocities against Indigenous Peoples in California as genocide,[90][91][92][93] as does Mohamed Adhikari,[94] and historian Brendan Lindsay.[95] Benjamin Madley claims that there is denial of atrocities: "Justice demands that even long after the perpetrators have vanished, we document the crimes that they and their advocates have too often concealed, denied, or suppressed."[96]

Despite the well documented evidence of the widespread atrocities of the California genocide, the social science and history textbooks approved by the California Department of Education ignored the history of this genocide.[97][98] Robert K. Hitchcock says that during the California genocide, "California state legislators, administrators, Indian agents, and townspeople denied that a genocide was happening."[1]

Canada

In Canada, Justice Beverly McLachlin, of the Supreme Court, said that Canada's historical treatment of Indigenous Peoples was cultural genocide.[99] Professor David Bruce MacDonald argued that the Canadian government should recognize various atrocities committed against the Indigenous Peoples in Canada.[100] Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized in the context of the 2021 Canadian Indian residential schools gravesite discoveries.[101][102][103] Tricia E. Logan wrote that Canada has been in denial of the true costs of its colonial process.[104]

Dr. Rita Dahomey makes a number criticisms of the Canadian Museum of Human Rights (CMHR) including the centrality of the Holocaust in the museum, framing residential schools as assimilationist and not genocide, and denialism of the genocidal nature of settler colonialism.[21] The CMHR opened in 2014 receiving criticism after the museum would not use the term genocide to describe the history of colonialism in Canada. In 2019, the museum reversed its policy, and officially recognizes genocide of Indigenous Peoples in Canada in its content.[105]

Senator Lynn Beyak generated controversy and accusations of genocide denial in the Canadian Indian residential school system and voiced disapproval of the final Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada report, saying that it had omitted the positives of the schools.[106][107][108] Former Conservative Party leader Erin O´Toole said that the residential school system educated Indigenous children, but then changed his view: "The system was intended to remove children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions, and cultures". Former publisher Conrad Black and others have also been accused of denialism.[109] [110][111][112][113][114]

Africa

In Britain, the Foreign Office kept documents related to the British Empire in a secret archive at Hanslope Park, north of London. Documents in the archive detailed a high level cover up of the deaths of 11 men killed by prison guards during the Mau Mau rebellion.[115] Opinions are divided on whether the government successfully covered up the violence used in the repression of the Mau Mau, with some authors pointing out that documents in Hans-lope Park had already been released in the 1980s.[116] The repression used by colonial authorities[117] had been documented in a number of academic works.[116]

In Belgium, the atrocities in the Congo Free State are not in the public discourse, and the topic is not addressed in education.[118][119] King Leopold II burned the colonial archive for eight days to cover up evidence of atrocities.[120] The archive of the colony was destroyed and the king said, "they have no right to know what I did there".[121]

In 1999, Adam Hochschild published King Leopold's Ghost, an award-winning book (and a documentary) about the atrocities committed in the Congo Free State.[122] The American Historical Association has awarded the book and claimed that Belgium has come to terms with this history because of the book.[123]

Australia

During the colonization of Australia, the Indigenous Australian population experienced the Australian frontier wars in which there was conflict over land. Massacres and mass poisonings have also been carried out against Indigenous people.[124] The Bringing Them Home report highlighted the abuse committed against Australian Indigenous Peoples by forceful removal of children from Indigenous families in what is called Stolen Generations.[125] Nonetheless, former Prime Minister John Howard refused to apologize in the Motion of Reconciliation, claiming that the program had no genocidal intent.[126][127] A scholar that denies genocide in Australia is Keith Windshuttle, who was editor of Quadrant magazine, which produced material criticizing the report.[9]

In Australia there are ongoing debates about the interpretation of history, called History Wars, for example, the calling of Australia's national myth as an invasion or settlement.[128][129][127][130][131] The near-destruction of Tasmania's Aboriginal population has been described as an act of genocide by historians including, Mohamed Adhikari, Benjamin Madley, and Ashley Riley Sousa.[132][92][133]

Historian Jurgen Zimmerer has written that there is denial of genocide of the Aborigines by Australian conservatives. Historian Dirk Moses says that in Australia there were many cultural-linguistic Indigenous groups, so there was not one single genocidal event by the colonizing perspective, but multiple ones: "...many genocides took place in Australia".[5]

According to Hannah Baldry there is ongoing denial: "The Australian Government appears to have long suffered a form of ‘denialism’ that has consistently deprived the country’s Aboriginal population of acknowledgment of the crimes perpetrated against their ancestors."[134]

Russia

Some scholars describe Russia as a settler colonial state, particularly in its expansion into Siberia and the Russian Far East, during which it displaced and resettled Indigenous Peoples, while practicing settler colonialism.[135][136][137] The annexation of Siberia and the Far East to Russia was resisted by the Indigenous Peoples, while the Cossacks often committed atrocities against the Indigenous Peoples.[138] During the Cold War, new forms of Indigenous repression were practiced.[139]

Other denials

There are a number of historians that do not consider that genocide of Indigenous Peoples took place in North America, including James Axtell, Robert Utley, William Rubinstein, Guenter Lewy and Gary Anderson, although some call the atrocities another name such as ethnic cleansing.[96][1] Stephen T. Katz has argued that the Holocaust is the only genocide that has occurred in history.[140][141]

Reactions to denial

Many countries in Europe have laws against Holocaust denial[142] but there are no known laws against Indigenous genocide denial. In Canada, some lawmakers want to criminalize the denial of genocide in residential schools: "They say they're being flooded with emails, letters and phone calls from people pushing back against the reports of suspected graves and skewing the history of the government-funded, church-run institutions that worked to assimilate more than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children for more than a century."[143]

In 2022, the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect issued a policy paper titled "Combating Holocaust and Genocide Denial: Protecting Survivors, Preserving Memory, and Promoting Prevention" in which genocide denial is often associated with hate speech, specifically when directed to specific identifiable groups. The report gives policy recommendations for states and UN officials in the matter of denial.[144]

Settler colonialism and genocide

Historian Samuel Totten and Professor Robert K. Hitchcock stated in their work on genocide historiography that the genocide of Indigenous Peoples became an public issue for many until after the last part of the twentieth century.[145] The following is a description of scholarly work from this period claiming a relation between settler colonialism and genocide.

Ann Curthoys

Ann Curthoys is an Australian historian and academic who writes about the view of genocide scholar Leo Kuper: "Nevertheless, the course of colonization of North and South America, the West Indies, and Australia and Tasmania, [Leo] Kuper observes, has certainly been marked all too often by genocide."[146]

Benjamin Madley

Benjamin Madley highlights that the Genocide Convention designates genocide a crime whether committed in time of peace or war. He has argued that the violent resistance to genocide has been described as wars or battles, instead of a genocide or a war of resistance. For example, for every white man killed, a hundred [California] Indians paid the penalty with their lives.[93] He proposed a case study of the Modoc War, comparing details of both sides in the conflict, to support this point. He says that throughout the world, victims many times violently resist colonial genocide.[6]

Bernard Baylin

Pulitzer prize winning historian Bernard Baylin has said that the Dutch and English conquests were just as brutal as those of the Spanish and Portuguese, in certain places and in certain times "genocidal".[147] He says that this history, for example the Pequot War, is not erased but conveniently forgotten.[20] The different European colonizing powers were all similarly cruel in their dealings with Indigenous Peoples.[148]

Canadian Historical Association

The association has maintains that the Canadian historical profession was complicit in denialism[149] and also said in a statement: ''Settler governments, whether they be colonial, imperial, federal, or provincial have worked, and arguably still work, towards the elimination of Indigenous peoples as both a distinct culture and physical group.''[150] Many historians disagreed and issued a letter against and for the claim of consensus in the view of this aspect of Canadian history.[151][152][153]

David Moshman

David Moshman, a Professor at University of Nebraska–Lincoln, highlighted the lack of awareness of the fact that Indigenous nations are not a monolithic entity, and many have disappeared: "The nations of the Americas remain virtually oblivious to their emergence from a series of genocides that were deliberately aimed at, and succeeded in eliminating, hundreds of indigenous cultures."[154]

David Stannard

David Stannard historian and professor of American Studies at the University of Hawaii compares the genocidal process in two cases of colonization, and says that the British did not need massive labor as the Spanish, but land: "And therein lies the central difference between the genocide committed by the Spanish and that of the Anglo-Americans: in British America extermination was the primary goal." Thus, many times they would clear the land of Indigenous nations, and put the few survivors in reserves.[155]

Gregory D. Smithers

Gregory D. Smithers, a lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Aberdeen, has weighed in as well: "Ward Churchill refers to settler colonialism in North America as ‘the American holocaust’, and David Stannard similarly portrays the European colonization of the Americas as an example of ‘human incineration and carnage’."[156]

Leo Kuper

South African scholar Leo Kuper, explained why the genocide of Indigenous Peoples has been dismissed in academic studies. He says that settler colonialism can be described as a genocidal process via massacres, land appropriation, epidemics and forced labor.[157]

Mahmood Mamdani

According to Mahmood Mamdani, in general, Indigenous societies did not necessarily consider land private property. Australian anthropologist Patrick Wolfe says that physical removal from their land resulted in the loss of means of subsistence, as the land was privatized and off limits to Indigenous Peoples.[158] Some Western thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes rationalized the appropriation of land saying that the land belonged to those that developed it.[159]

Mark Levene

Mark Levene is a historian at University of Southampton, linked colonialism and genocide: "In this, of course, we come back to the fatal nexus between the Anglo-American drive to rapid state-building and genocide."[160]

Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky has considered settler colonialism to be the most vicious form of imperialism, and describes the lack of self-awareness of the genocide by some Americans.[161][162][26]

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, an American historian, professor at California State University, describes settler colonialism as inherently genocide in terms of the Genocide convention. She points out that genocide does not have to be total to be genocide, as the most famous genocide (the Holocaust) of all was not total.[163]

Stephen Howe

Stephen Howe, professor in the History and Cultures of Colonialism at the University of Bristol, UK, relates colonialism with genocide and says the case for colonialism causing genocide is very strong.[164]

Other personalities

Phil Fontaine, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, wrote:[165]

The Government of Canada currently recognizes five genocides: the Holocaust, the Holodomor, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide and Srebrenica. The time has come for Canada to formally recognize a sixth genocide, the genocide of its own aboriginal communities;

Members of the Penobscot Nation in Maine made an educational film about how settlers killed Indigenous Peoples during the colonial era:[166]

The filmmakers say they simply want to ensure this history isn't whitewashed by promoting a fuller understanding of the nation's past.

Indigenous actor Russell Means wrote in 1992 about denial in the United States, inspiring the title of a book by Ward Churchill:[167]

...there's a little matter of genocide that's got to be taken into account right here at home. I’m talking about the genocide which has been perpetrated against American Indians...

In 1973, American actor Marlon Brando declined an Academy Award in protest for the representation of Native Americans in Hollywood cinema, citing killing of helpless unarmed Indigenous Peoples and the theft of their land.[168]

In 2023, Indigenous leaders from Antigua and Barbuda, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Australia, the Bahamas, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines issued an open letter. The signed letter requests King Charles III to acknowledge at his coronation the “horrific impacts” of colonization.[169][170][171]

Prevention

Atrocity denial may be reduced by works of history, knowledge gathering, preservation of archives, documentation of records, investigation panels, international tribunals, application of international law, search for missing persons, commemorations, public apologies, development of truth commissions, educational programs, memorials, museums, documentaries, films and other mass media. According to Johnathan Sisson, the society has the right to know the truth about historical events and facts, and the circumstances that led to massive or systematic human rights violations. He says that the State has the obligation to secure records and other evidence to prevent historical revisionism. The goal is to prevent recurrence in the future.[172][173]

Further study

Benjamin Madley studied two cases of genocide (Pequot and Yuki) analyzing four elements: statements of genocidal intent, presence of massacres, state-sponsored body-part bounties (rewards officially paid for corpses, heads and scalps) and mass death in government custody. He suggests that detailed breakdown of genocide studies by individual nation is a new direction in genocide studies: "...offering a powerful tool with which to understand genocide and combat its denial around the world."[96]

See also

- Analysis of Western European colonialism and colonization

- Atrocities in the Congo Free State

- Cambodian genocide denial

- Denialism

- Genocide denial

- Genocide of Indigenous Peoples

- Genocides in history

- Genocide recognition politics

- Historical negationism

- Historical revisionism

- History wars

- Holocaust denial

- Pseudohistory

- Truth commission

Further reading

- Adhikari, Mohamed (2021). Civilian-Driven Violence and the Genocide of Indigenous Peoples in Settler Societies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-41177-5. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023.

- Anderson, E. N.; Anderson, Barbara (2020). Complying with Genocide: The Wolf You Feed. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-7936-3460-3. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023.

- Anderson, Gary Clayton. 2005. The Conquest of Texas : Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land 1820–1875. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-806-13698-1.

- Barta, Tony (2008). "With Intent to Deny: On Colonial Intentions and Genocide Denial". Journal of Genocide Research. 10 (1): 111–119.

- "Introduction. By Jeff Benvenuto, Andrew Woolford, and Alexander Laban Hinton. Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America". Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America. Duke University Press. 2020. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1515/9780822376149-002. ISBN 9780822376149. S2CID 243002850.

- Bischoping, Katherine; Fingerhut, Natalie (14 July 2008). "Border Lines: Indigenous Peoples in Genocide Studies". Canadian Review of Sociology. 33 (4): 481–506. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618X.1996.tb00958.x.

- Brito, Alexandra Barahona De; Gonzalez Enriquez, Carmen; Aguilar, Paloma, eds. (2001). The Politics of Memory and Democratization. doi:10.1093/0199240906.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-924090-6.

- Cesaire, Aime. (1972). Discourse on Colonialism. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- Chomsky, Noam (3 September 2010). "Genocide Denial with a Vengeance: Old and New Imperial Norms". Monthly Review. 62 (4): 16–20. doi:10.14452/MR-062-04-2010-08_3.

- Churchill, Ward (1998). A Little Matter Of Genocide: Holocaust And Denial In The Americas 1492 To The Present. San Francisco CA: City Lights Books. ISBN 978-0-87286-323-1.

- Churchill, Ward (February 2000). "Forbidding the 'G-Word': Holocaust Denial as Judicial Doctrine in Canada". Other Voices. 2 (1).

- Churchill, Ward (January 2003). "An American holocaust? The structure of denial". Socialism and Democracy. 17 (1): 25–75. doi:10.1080/08854300308428341. S2CID 143631746.

- Cook, Anna (2016). "A politics of Indigenous voice: reconciliation, felt knowledge and settler denial". The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. 36 (2): 69–80. ProQuest 1938073834.

- Cook, Anna (2017). "Intra-American Philosophy in Practice: Indigenous Voice, Felt Knowledge, and Settler Denial". The Pluralist. 12 (1): 74–84. doi:10.5406/pluralist.12.1.0074. S2CID 151807002.

- Der Matossian, Bedross (2023), ed., Chapter 1: "Denial of Genocide of Indigenous People in the United States" by Robert K. Hitchcock in Denial of Genocides in the Twenty-First Century Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-4962-2510-8

- Dudley, M. Q. (2017). A Library Matter of Genocide: The Library of Congress and the Historiography of the Native American Holocaust. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(2).

- Fenelon, James V.; Trafzer, Clifford E. (January 2014). "From Colonialism to Denial of California Genocide to Misrepresentations: Special Issue on Indigenous Struggles in the Americas". American Behavioral Scientist. 58 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1177/0002764213495045. S2CID 145377834.

- Hennebel, Ludovic, and Thomas Hochmann (eds), Genocide Denials and the Law (2011), ISBN 9780199738922 https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199738922.001.0001

- Hinton, Alexander Laban (2014). Hidden Genocides: Power, Knowledge, Memory. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6162-2. JSTOR j.ctt5hjdfm.

- Hitchcock, Robert K.; Twedt, Tara M. (2004). "Chapter 13 Physical and Cultural Genocide of Indigenous Peoples". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. (eds.). Century of genocide : critical essays and eyewitness accounts. (3rd ed.). New York : Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94429-8.

- Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 0-330-49233-0.

- Kiernan, Ben. (2007). Blood and soil: A world history of genocide and extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300144253. Archived

- Kiernan, Ben (June 2002). "Cover-up and Denial of Genocide: Australia, the USA, East Timor, and the Aborigines". Critical Asian Studies. 34 (2): 163–192. doi:10.1080/14672710220146197. S2CID 146339164.

- Kuper, Leo (1991). "When Denial Becomes Routine". Social Education. 55 (2): 121–23. ERIC EJ427728.

- Lemarchand, Rene (2011). Forgotten Genocides: Oblivion, Denial, and Memory. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-2263-0. JSTOR j.ctt3fhnm9.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02793-7.

- Manne, Robert (Ed.) (2003). "Revisionism and Denial," Whitewash: On Keith Windshuttle’s Fabrication of Aboriginal History (Melbourne: Black Inc.), 337-370.

- Manne, Robert. (2001). Quarterly Essay: In Denial—the Stolen Generations and the Right. Melbourne: Morry Schwartz, Black Inc., 113 pp.

- McMillan, Mark; Rigney, Sophie (16 March 2018). "Race, reconciliation, and justice in Australia: from denial to acknowledgment". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 41 (4): 759–777. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1340653. S2CID 148769763.

- Moses, A.Dirk (October 2002). "Conceptual blockages and definitional dilemmas in the 'racial century': genocides of indigenous peoples and the Holocaust". Patterns of Prejudice. 36 (4): 7–36. doi:10.1080/003132202128811538. S2CID 145222840.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2003) “Revisionism and Denial,” in Robert Manne, ed., Whitewash: On Keith Windshuttle’s Fabrication of Aboriginal History (Melbourne: Black Inc.), 337-370.

- Moshman, David (November 2001). "Conceptual constraints on thinking about genocide". Journal of Genocide Research. 3 (3): 431–450. doi:10.1080/14623520120097224. PMID 19670511. S2CID 2734032.

- Panich, Lee M.; Schneider, Tsim D. (October 2019). "Categorical Denial: Evaluating Post-1492 Indigenous Erasure in the Paper Trail of American Archaeology". American Antiquity. 84 (4): 651–668. doi:10.1017/aaq.2019.54. S2CID 203352706.

- Short, Damien (2016). Redefining Genocide: Settler Colonialism, Social Death and Ecocide. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-84813-546-8. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023.

- Smith, R. W. (2014). Genocide Denial and Prevention. Genocide Studies International, 8(1), 102–109. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26985995

- Slocum, Melissa Michal (30 December 2018). "Introduction: There Is No Question of American Indian Genocide". Transmotion. 4 (2): 1–30. doi:10.22024/UniKent/03/tm.651.

- Survival International (1993). The Denial of Genocide. London: Survival International.

- Synott, John P. (1993). "Genocide and Cover-up Practices of the British Colonial System Against Australian Aborigines, 1788–1992". Internet on the Holocaust and Genocide: 44–46:15–16.

- Totten, Samuel; Hitchcock, Robert K., eds. (2017). Genocide of Indigenous Peoples. doi:10.4324/9780203790830. ISBN 978-0-203-79083-0. S2CID 152960532.

- Wolfe, Patrick (December 2006). "Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native". Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (4): 387–409. doi:10.1080/14623520601056240. S2CID 143873621.

- Woolford, Andrew; Benvenuto, Jeff (2 October 2015). "Canada and colonial genocide". Journal of Genocide Research. 17 (4): 373–390. doi:10.1080/14623528.2015.1096580. S2CID 74263719.

External links

- IWGIA – International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. iwgia.org.

- Cultural Survival. Indigenous advocacy organization founded in 1972.

- Genocide and ethnocide, Encyclopedia.com

- Genocide Watch founded Founded by Gregory H. Stanton, a genocide scholar and former president of International Association of Genocide Scholars. See for example report covering denial of genocide in Canada against Indigenous Peoples here.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Calls to Action. Calls to Action, document

References

- ^ a b c d e Hitchcock, Robert K. (2023). "Denial of Genocide of Indigenous People in the United States". In Der Matossian, Bedross (ed.). Denial of genocides in the twenty-first century. [Lincoln]: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 33, 35, 36, 43, 44, 46, 47. ISBN 978-1-4962-3554-1. OCLC 1374189062.

Genocide scholars Susan Chavez Cameron and Loan T. Phan see American Indians as having gone through the ten stages of genocide identified by Stanton. Failure to acknowledge genocide has harmful social and psychological impacts on the victims of genocide, and it leaves the perpetrators in positions of power vis-a-vis others in their societies. As Agnieszka Bienczyk-Missala points out, denial or negation relating to mass crimes consists of denying scientifically proven historical facts by deliberately concealing them and spreading false and misleading information. She goes on to say that the consequences of negationism are of ethical, legal, social, and political character.

- ^ "Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes: A Tool for Prevention" (PDF). United Nations Office of the Prevention of Genocide. 2014. p. 1.

The definitions of the crimes can be found in the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their 1977 Additional Protocols, and the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, among other treaties.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Defining the Four Mass Atrocity Crimes". Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ "What is atrocity prevention? | GAAMAC". Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ a b Zimmerer, Jurgen (2004). Moses, Dirk (ed.). Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and Stolen Indigenous Children in Australian History. Berghahn Books. pp. 19, 51. ISBN 978-1-57181-410-4.

In that case, many genocides took place in Australia, rather than being the site of a single genocidal event. (p19) The question of colonial genocide is disturbing, in part because it increases the number of mass murders regarded as genocide, and in part, too, because it calls into question the Europeanization of the globe as a modernizing project. Where the descendants of perpetrators still comprise the majority or a large proportion of the population, and control political life and public discourse, recognition of colonial genocides is even more difficult, as it undermines the image of the past on which national identity is built. (p51)

- ^ a b c d Woolford, Andrew; Benvenutto, Jeff; Hinton, Alexander Laban (2014). Fontaine, Theodore (ed.). Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America. Duke University Press. pp. 9, 11, 120, 150, 160. ISBN 978-0-8223-5763-6. JSTOR j.ctv11sn770.

As such it is important for the peoples of the United States and Canada to recognize their shared legacies of genocide, which have too often been hidden, ignored, forgotten, or outright denied. (p3) After all, much of North America was swindled from Indigenous peoples through the mythical but still powerful Doctrine of Discovery, the perceived right of conquest, and deceitful treaties. Restitution for colonial genocide would thus entail returning stolen territories. (p9) Thankfully a new generation of genocide scholarship is moving beyond these timeworn and irreconcilable divisions. (p11) Memory, remembering, forgetting, and denial are inseparable and critical junctures in the study and examination of genocide. Absence or suppression of memories is not merely a lack of acknowledgment of individual or collective experiences but can also be considered denial of a genocidal crime (p150). Erasure of historical memory and modification of historical narrative influence the perception of genocide. If it is possible to avoid conceptually blocking colonial genocides for a moment, we can consider denial in a colonial context. Perpetrators initiate and perpetuate denial (p160).

- ^ Hinton, Alexander Laban (2014). Hidden Genocides: Power, Knowledge, Memory. Rutgers University Press. pp. 2, 3. ISBN 978-0-8135-6162-2. JSTOR j.ctt5hjdfm.

From Lemarchand's volume, it is clear that what is remembered and what is not remembered is a political choice, producing a dominant narrative that reflects the victor's version of history while silencing dissenting voices. Building on a critical genocide studies approach, this volume seeks to contribute to this conversation by critically examining cases of genocide that have been "hidden" politically, socially, culturally, or historically in accordance with broader systems of political and social power. (p2) ...the U.S. government, for most of its existence, stated openly and frequently that its policy was to destroy Native American ways of life through forced integration, forced removal, and death. An 1881 report of the U.S. commissioner of Indian Affairs on the "Indian question" is indicative of the decades- long policy: "There is no one who has been a close observer of Indian history and the effect of contact of Indians with civilization who is not well satisfied that one of two things must eventually take place, to wit, either civilization or extermination of the Indian. Savage and civilized life cannot live and prosper on the same ground. One of the two must die." (p3)

- ^ Campbell, Bradley (2009). "Genocide as Social Control". Sociological Theory. 27 (2): 150–172. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01341.x. JSTOR 40376129. S2CID 143902886.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. pp. 208, 230, 791–793. ISBN 978-1-136-93797-2.

- ^ "Indian Tribes and Resources for Native Americans | USAGov". www.usa.gov. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

The U.S. government officially recognizes 574 Indian tribes in the contiguous 48 states and Alaska.

- ^ Totten, Samuel; Hitchcock, Robert K. (2011). Genocide of Indigenous Peoples: A Critical Bibliographic Review. Transaction Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4128-4455-0.

In Asia, for example, only one country, the Philippines, has officially adopted the term "Indigenous peoples," and established a law specifically to protect Indigenous peoples' rights. Only two countries in Africa, Burundi and Cameroon, have statements about the rights of Indigenous peoples in their constitutions.

- ^ Englert, Sai (November 2020). "Settlers, Workers, and the Logic of Accumulation by Dispossession". Antipode. 52 (6): 1647–1666. doi:10.1111/anti.12659. S2CID 225643194.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (7 September 2017). "Europe's First Settler Colonial Incursion into Africa: The Genocide of Aboriginal Canary Islanders". African Historical Review. 49 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1080/17532523.2017.1336863. S2CID 165086773.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (2022). Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-1-64792-054-8.

- ^ Ibrahim, Emily Prey, Azeem. "The United States Must Reckon With Its Own Genocides". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Opinion | The U.S. has finally acknowledged the genocide of Armenians. What about Native Americans?". Washington Post. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Aranda, Dario (2010). Aboriginal Argentina: Genocide, Loot and Resistance (Argentina Originaria: Genocidios, Saqueos y Resistencias) (in Spanish) (1st ed.). IWGIA – International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. ISBN 978-987-21900-6-4. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Ward, Churchill, A Little Matter Of Genocide: Holocaust And Denial In The Americas 1492 To The Present (San Francisco CA: City Lights Books, 1998) pages 1-17. ISBN 978-0-87286-323-1 (paperback); ISBN 978-0-87286-343-9 (hardcover)).

- ^ Churchill, Ward, "Forbidding the "G-Word": Holocaust Denial as Judicial Doctrine in Canada," Archived 31 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Other Voices 2.1 (February 2000), accessed 13 February 2007.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, Ron. "The Shocking Savagery of America's Early History". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ a b Kaur Dhamoon, Rita (March 2016). "Re-presenting Genocide: The Canadian Museum of Human Rights and Settler Colonial Power". Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics. 1 (1): 5–30. doi:10.1017/rep.2015.4.

I contend that the curatorial decision of the CMHR to not use the label of genocide in the title of the core gallery on Indigenous perspectives was specifically a form of interpretive denial.

- ^ White, Richard (17 August 2016). "Naming America's Own Genocide". Retrieved 29 March 2023.

In defining genocide, Madley relies on the criteria of the United Nations Genocide Convention, which has served as the basis for the genocide trials of defendants from Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia and has been employed at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

- ^ Charny, Israel W. (February 1997). "Toward a Generic Definition of Genocide". In Andreopoulos, George J. (ed.). Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8122-1616-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Stanton, Gregory (2020). "The Ten Stages of Genocide". Genocide Watch. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020.

Phase 4. One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects or diseases. Dehumanization overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder. Phase 10. During and after genocide, lawyers, diplomats, and others who oppose forceful action often deny that these crimes meet the definition of genocide. They call them euphemisms like "ethnic cleansing" instead. They question whether intent to destroy a group can be proven, ignoring thousands of murders. They overlook deliberate imposition of conditions that destroy part of a group. They claim that only courts can determine whether there has been genocide, demanding "proof beyond a reasonable doubt", when prevention only requires action based on compelling evidence.

- ^ Herman, Edward S.; Chomsky, Noam (1988). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. Pantheon Books. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-394-54926-2.

- ^ a b Jones, Adam (7 May 2020). "Chomsky and Genocide". Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal. 14 (1): 76–104. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.14.1.1738. S2CID 218959996.

- ^ a b c Hitchcock, Robert K.; Twedt, Tara M. (1997). "Chapter 13 Physical and Cultural Genocide of Indigenous Peoples". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. (eds.). Century of genocide : critical essays and eyewitness accounts. Internet Archive (3rd ed.). New York : Routledge. pp. 353, 362. ISBN 978-0-415-94429-8.

Most states, along with the United Nations, have been reluctant to criticize individual nations for their actions on the pretense that this would constitute a violation of sovereignty. They have also tended to accept government denials of genocides at face value. As a result, genocidal actions continue.

- ^ Totten, Samuel; Hitchcock, Robert K. (2011). Genocide of Indigenous Peoples: A Critical Bibliographic Review. Transaction Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4128-4455-0.

- ^ Miles, William F. S. (2014). Scars of Partition: Postcolonial Legacies in French and British Borderlands. U of Nebraska Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8032-6771-8.

Anglo-French carving of colonial space is a significant geographical legacy: nearly 40 percent of the entire length of today's international boundaries were traced by Britain and France.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-136-93797-2.

- ^ "Indigenous definition". Merriam-Webster. 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

of or relating to the earliest known inhabitants of a place and especially of a place that was colonized by a now-dominant group.

- ^ Nations, United. "Indigenous Peoples". United Nations. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Blatz, Craig W.; Schumann, Karina; Ross, Michael (2009). "Government Apologies for Historical Injustices". Political Psychology. 30 (2): 219–241. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00689.x. JSTOR 25655387.

- ^ "'Keating told the truth': Stan Grant, Larissa Behrendt and others remember the Redfern speech 30 years on". The Guardian. 9 December 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Lightfoot, Sheryl (2015). "Settler-State Apologies to Indigenous Peoples: A Normative Framework and Comparative Assessment". Native American and Indigenous Studies. 2 (1): 15–39. doi:10.5749/natiindistudj.2.1.0015. S2CID 156826767.

- ^ "Belgian king expresses 'deepest regrets' for wounds inflicted in Congo". euronews. 8 June 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Belgian king expresses regrets for colonial abuses". BBC News. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Rob Picheta (1 July 2020). "Belgium's King sends 'regrets' to Congo for Leopold II atrocities – but doesn't apologize". CNN. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "Belgium apology for mixed-race kidnappings in colonial era". BBC News. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Milan Schreuer (4 April 2019). "Belgium Apologizes for Kidnapping Children From African Colonies". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Dixon, Robin (6 June 2013). "British government apologizes for colonial abuses in Kenya". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Text of Stephen Harper's residential schools apology". CTVNews. 11 June 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Trudeau apologizes to Newfoundland residential school survivors left out of 2008 apology, compensation". thestar.com. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Governor Newsom Issues Apology to Native Americans for State's Historical Wrongdoings, Establishes Truth and Healing Council". California Governor. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ "Germany apologizes for colonial-era genocide in Namibia". Reuters. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Corntassel, Jeff; Holder, Cindy (1 December 2008). "Who's Sorry Now? Government Apologies, Truth Commissions, and Indigenous Self-Determination in Australia, Canada, Guatemala, and Peru". Human Rights Review. 9 (4): 465–489. doi:10.1007/s12142-008-0065-3. S2CID 53969690.

- ^ "Mexico marks end of last Indigenous revolt with apology". AP NEWS. 3 May 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Dutch PM Mark Rutte apologises for country's role in the slave trade". euronews. 19 December 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Cineas, Fabiola (17 January 2023). "New Zealand's Māori fought for reparations — and won". Vox. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Jan. 17, 1893 | Hawaiian Monarchy Overthrown by America-Backed Businessmen". The Learning Network. 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

In 1993, Congress issued an apology to the people of Hawaii for the U.S. government's role in the overthrow and acknowledged that 'the native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty'.

- ^ "A sorry saga: Obama signs Native American apology resolution; fails to draw attention to it | Indian Law Resource Center". indianlaw.org. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Gover, Kevin (2000). "Remarks of Kevin Gover, Assistant Secretary Indian Affairs: Address to Tribal Leaders". Journal of American Indian Education. 39 (2): 4–6. JSTOR 24398427.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (22 September 2014). "John Howard: there was no genocide against Indigenous Australians". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Janna (May 2009). "Apology, historical obligations and the ethics of memory". Memory Studies. 2 (2): 195–210. doi:10.1177/1750698008102052. S2CID 145294135.

- ^ Yardley, Jim; Neuman, William (10 July 2015). "In Bolivia, Pope Francis Apologizes for Church's 'Grave Sins'". The New York Times.

- ^ "Pope apologizes for 'catastrophic' school policy in Canada". AP NEWS. 25 July 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Pope Francis: It was a genocide against indigenous peoples – Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

It's true, I didn't use the word because it didn't come to my mind, but I described the genocide and asked for forgiveness, pardon for this activity that is genocidal. For example, I condemned this too: taking away children, changing culture, changing mentality, changing traditions, changing a race, let's put it that way, an entire culture. Yes, genocide is a technical word. I didn't use it because it didn't come to my mind, but I described it… It's true, yes, yes, it's genocide. You can all stay calm about this. You can report that I said that it was genocide.

- ^ "Vatican rejects doctrine that fueled centuries of colonialism". AP NEWS. 30 March 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Sanders, Leanne (2 May 2022). "'I am ashamed, I am horrified': Archbishop of Canterbury expresses remorse over church's role residential schools". APTN News.

- ^ Bush, Peter G. (2015). "The Canadian Churches' Apologies for Colonialism and Residential Schools, 1986–1998". Peace Research. 47 (1/2): 47–70. JSTOR 26382582.

- ^ Handy, Gemma (24 April 2018). "Archaeologists say early Caribbeans were not 'savage cannibals', as colonists wrote". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Whitehead, Neil L. (1984). "Carib cannibalism. The historical evidence". Journal de la société des américanistes. 70 (1): 69–87. doi:10.3406/jsa.1984.2239. JSTOR 24606255.

- ^ Rebecca Earle, The Body of the Conquistador: Food, race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. New York: Cambridge University Press 2012, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Brantlinger, Patrick (2011). Taming Cannibals: Race and the Victorians (1 ed.). Cornell University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8014-5019-8. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt7zgmt.

Dark Vanishings (2003) analyzed the pervasive discourse of blaming the victim that treated many indigenous populations as causing their own extinction. Savagery was supposedly a principal cause; besides warfare, savages practiced infanticide, widow strangling, and cannibalism, all held to be self-exterminating customs. It was frequently also asserted that many or perhaps all 'primitive races' were doomed by the forward march of 'the white man' and 'civilization'.

- ^ Stannard, David E. (1993). American holocaust : the conquest of the New World. Internet Archive. New York : Oxford University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

If the assertions of Ortiz and others regarding the habits of the Indians were fabrications, they were not fabrications without design. From the Spaniards' enumerations of what they claimed were the disgusting food customs of the Indians (including cannibalism, but also the consumption of insects and other items regarded as unfit for human diets) to the Indians' supposed nakedness and absence of agriculture, their sexual deviance and licentiousness, their brutish ignorance, their lack of advanced weaponry and iron, and their irremediable idolatry, the conquering Europeans were purposefully and systematically dehumanizing the people they were exterminating.

- ^ Stannard, David E. (1993). American holocaust : the conquest of the New World. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- ^ Fernández-Santamaria, José A. (1975). "Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda on the Nature of the American Indians". The Americas. 31 (4): 434–451. doi:10.2307/980012. JSTOR 980012. S2CID 147379509.

- ^ "Chapter 5. Genocide in Tasmania?". Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and Stolen Indigenous Children in Australian History (1 ed.). Berghahn Books. 2012. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-57181-411-1. JSTOR j.ctt9qdg7m.

This is equally true of genocide-in two ways. For all individual German to kill a Jew or a Gypsy, just because of the race of the victim, is an act of genocide. But to accuse the machinery of State under which such killings took place as an act of policy requires proof that this is their aim. There is ample proof that this was the aim of the "Final Solution". Jews were to be killed because they were not human, just as the Tasmanian Aborigines were hunted to death for the same reason.

- ^ Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (12 May 2016). "Yes, Native Americans Were the Victims of Genocide | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Treuer, David (13 May 2016). "Review: The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Tatz, Colin (2001). "Confronting Australian genocide". Aboriginal History. 25: 16–36. JSTOR 45135469. PMID 19514155.

Denialism takes several forms. First, the denial of any past genocidal behavior, whether physical killing or child removal. Second, the somewhat bizarre counterview that whites have been the victims. Third, the hypothesis that concentration on unmitigated gloom, or on the black armband view of history, overwhelms the reality that there has been more good than bad in Australian race relations.

- ^ Hitchcock, Robert (2014). "Indigenous Populations". In Bartrop, Paul R.; Jacobs, Steven Leonard (eds.). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection [4 volumes]: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. pp. 4239–4246. ISBN 978-1-61069-364-6.

- ^ Kuper, Leo (1991). "When Denial Becomes Routine". Social Education. 55 (2): 121–23. OCLC 425009321. ERIC EJ427728 ProQuest 210628314.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2005). A People's History of the United States. Internet Archive. HarperPerennial Modern Classics. ISBN 978-0-06-083865-2.

From first grade to graduate school, I was given no inkling that the landing of Christopher Columbus in the New World initiated a genocide, in which the indigenous population of Hispaniola was annihilated. Or that this was just the first stage of what was presented as a benign expansion of the new nation (Louisiana "Purchase," Florida "Purchase," Mexican "Cession"), but which involved the violent expulsion of Indians, accompanied by unspeakable atrocities, from every square mile of the continent, until there was nothing to do with them but herd them into reservations. (Afterword)

- ^ Barkan, Elazar (2003). "Chapter 6. Genocides of Indigenous Peoples". In Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben (eds.). The specter of genocide : mass murder in historical perspective. Internet Archive. New York : Cambridge University Press. pp. 131, 138–139. ISBN 978-0-521-82063-9.

The United States had its own long-standing boarding schools for Native American children with a similar extent of abuse. However, the term Education for Extinction is yet to capture public attention as a human rights issue. The American indigenous dilemma is far less central to U.S. mainstream politics than in any of the other ex-British colonies. The notion of genocide, while warranted as much or more than in those other countries, is still confined to radical writers. It is intriguing, indeed, that no mainstream American historians have written about the fate of the Native Americans as genocide. (p131) Thus, the European guilt was at least a collective myopia, a deep failure to acknowledge the equality of indigenous people and the vast number and varied array of atrocities and genocides inflicted upon them. More likely this has been a willful denial of responsibility and guilt, hiding behind the structural explanation of biological agents. It is time to reverse course and acknowledge the responsibility and extent of the destruction purposefully inflicted by colonialism, although not upon all indigenous peoples, and not in similar fashion. (p138-139)

- ^ Stannard, David E. (1992). "Genocide in the Americas". The Nation. 255 (12): 430–434.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (19 October 1992). "Minority Report". The Nation. Vol. 255, no. 12.

- ^ Stannard, David (2009). Rosenbaum, Alan S; Charny, Israel W (eds.). Is the Holocaust Unique?: Perspectives on Comparative Genocide. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 298. doi:10.4324/9780429495137. ISBN 978-0-8133-3686-2.

To Hitchens, anyone who refused to join him in celebrating with "great vim and gusto" the annihilation of the native peoples of the Americas was (in his words) self-hating, ridiculous, ignorant, and sinister. People who regard critically the genocide that was carried out in America's past, Hitchens continued, are simply reactionary, since such grossly inhuman atrocities "happen to be the way history is made." And thus "to complain about them is as empty as complaint about climatic, geological or tectonic shift." Moreover, he added, such violence is worth glorifying since it more often than not has been for the long-term betterment of humankind, as in the United States today, where the extermination of the Native Americans has brought about "a nearly boundless epoch of opportunity and innovation."

- ^ Stannard, David (2009). Rosenbaum, Alan S; Charny, Israel W (eds.). Is the Holocaust Unique?: Perspectives on Comparative Genocide. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 298. doi:10.4324/9780429495137. ISBN 978-0-8133-3686-2.

These are, of course, precisely the same sort of retrospective justifications for genocide that would have been offered by the descendants of Nazi storm troopers and SS doctors had the Third Reich ultimately had its way: that is, however distasteful the means, the extermination of the Jews was thoroughly warranted given the beneficial ends that were accomplished. In this light it is worth considering again what the reaction would be in Europe and elsewhere if the equivalent of the actual views of Krauthammer and Schlesinger and Hitchens were expressed today by the respectable press in Germany—but with Jews, not Native Americans, as the people whose historical near-extermination was being celebrated. And there is no doubt whatsoever that if that were to happen, alarm bells announcing a frightening and unparalleled postwar resurgence of German neo-Nazism would, quite justifiably, be going off immediately throughout the world.

- ^ Stannard, David (2009). Rosenbaum, Alan S; Charny, Israel W (eds.). Is the Holocaust Unique?: Perspectives on Comparative Genocide. Abingdon, England: Routledge. pp. 330–331. doi:10.4324/9780429495137. ISBN 978-0-8133-3686-2.

The willful maintenance of public ignorance regarding the genocidal and racist horrors against indigenous peoples that have been and are being perpetrated by many nations of the Western Hemisphere, including the United States—which contributes to the construction of a museum to commemorate genocide only if the killing occurred half a world away—is consciously aided and abetted and legitimized by the actions of the Jewish uniqueness advocates we have been discussing....and so all people of conscience must be on guard against Holocaust deniers who, in many cases, would like nothing better than to see mass violence against Jews start again. By that same token, however, as we consider the terrible history and the ongoing campaigns of genocide against the indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere...

- ^ Gamarekian, Barbara (10 April 1991). "Grants Rejected; Scholars Grumble". The New York Times.

- ^ Cox, John; Khoury, Amal; Minslow, Sarah (4 August 2021). "Beyond erasure: Indigenous genocide denial and settler colonialism by Michelle A. Stanley". Denial: The Final Stage of Genocide (1 ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 131, 135. doi:10.4324/9781003010708. ISBN 978-1-003-01070-8.

- ^ Cameron, Susan Chavez; Phan, Loan T. (2018). "Ten stages of American Indian genocide". Revista Interamericana de Psicología. 52 (1): 28. doi:10.30849/rip/ijp.v52i1.876 (inactive 30 March 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2023 (link) - ^ Korey, William (March 1997). "The United States and the Genocide Convention: Leading Advocate and Leading Obstacle". Ethics & International Affairs. 11: 271–290. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7093.1997.tb00032.x. S2CID 145335690.

- ^ Bradley, Curtis A.; Goldsmith, Jack L. (2000). "Treaties, Human Rights, and Conditional Consent". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. doi:10.2139/SSRN.224298. S2CID 153350639. SSRN 224298.

The United States attached a reservation to its ratification of the Genocide Convention, for example, stating that 'before any dispute to which the United States is a party may be submitted to the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice under [Article IX of the Convention], the specific consent of the United States is required in each case.'

- ^ Churchill, Ward (2000). Charny, Israel W. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Genocide. ABC-CLIO. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-87436-928-1.

The size of the aggregate native North American population in 1500 is currently estimated at about 15 million. By 1890 it had been reduced by some 97.5 percent, to less than a quarter-million. That year, it was announced that "aboriginal land-holdings" amounted to only 2.5 percent of US territory. Anglo-America's professed "manifest destiny" to acquire "living space" by liquidating the "inferior" peoples who owned it had been fulfilled.

- ^ Kuper, Leo (1982). Genocide : its political use in the twentieth century. Internet Archive. New Haven : Yale University Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-300-02795-2.

In contemporary extra-judicial discussions of allegations of genocide, the question of intent has become a controversial issue, providing a ready basis for denial of guilt.

- ^ "Video: American Holocaust: The Destruction of America's Native Peoples". Vanderbilt University. 30 October 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Perez, Sonia (15 May 2014). "Guatemala's congress votes to deny genocide". AP NEWS. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Madley, Benjamin (2016). "Understanding Genocide in California under United States Rule, 1846–1873". The Western Historical Quarterly. 47 (4): 449–461. doi:10.1093/whq/whw176.

- ^ Madley, Benjamin (1 August 2008). "California's Yuki Indians: Defining Genocide in Native American History". The Western Historical Quarterly. 39 (3): 303–332. doi:10.1093/whq/39.3.303.

- ^ a b Madley, Benjamin (2004). "Patterns of frontier genocide 1803–1910: the aboriginal Tasmanians, the Yuki of California, and the Herero of Namibia". Journal of Genocide Research. 6 (2): 167–192. doi:10.1080/1462352042000225930. S2CID 145079658.

- ^ a b Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0300181364.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (2022). Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 72–115. ISBN 978-1647920548.

- ^ Lindsay, Brendan C. (March 2015). Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846-1873. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6966-8.

- ^ a b c Madley, Benjamin (2015). "Reexamining the American Genocide Debate: Meaning, Historiography, and New Methods". The American Historical Review. 120 (1): 106,107,110,111,120,132,133,134. doi:10.1093/ahr/120.1.98. JSTOR 43696337.

The study of massacres defined here as predominantly one-sided intentional killings of five or more noncombatants or relatively poorly armed or disarmed combatants, often by surprise and with little or no quarter.

- ^ Fenelon, James V.; Trafzer, Clifford E. (4 December 2013). "From Colonialism to Denial of California Genocide to Misrepresentations: Special Issue on Indigenous Struggles in the Americas". American Behavioral Scientist. 58 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1177/0002764213495045. S2CID 145377834.

- ^ Trafzer, Clifford E.; Lorimer, Michelle (5 August 2013). "Silencing California Indian Genocide in Social Studies Texts". American Behavioral Scientist. 58 (1): 64–82. doi:10.1177/0002764213495032. S2CID 144356070.

- ^ Fine, Sean (28 May 2015). "Chief Justice says Canada attempted 'cultural genocide' on aboriginals". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ David MacDonald (4 June 2021). "Canada's hypocrisy: Recognizing genocide except its own against Indigenous peoples". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Matthew Kupfer (28 June 2021). "Indigenous people ask Canadians to 'put their pride aside' and reflect this Canada Day". CBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Maan Alhmidi (5 June 2021). "Experts say Trudeau's acknowledgment of Indigenous genocide could have legal impacts". Global News. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ MacDonald, David B. (2015). "Canada's history wars: indigenous genocide and public memory in the United States, Australia and Canada". Journal of Genocide Research. 17 (4): 411–431. doi:10.1080/14623528.2015.1096583. S2CID 74512843.

- ^ Logan, Tricia E. (2014). "Memory, Erasure, and National Myth". In Woolford, Andrew (ed.). Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America. Duke University Press. p. 149. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11sn770. ISBN 978-0-8223-5763-6. JSTOR j.ctv11sn770.

Canada, a country with oft-recounted histories of Indigenous origins and colonial legacies, still maintains a memory block in terms of the atrocities it committed to build the Canadian state. There is nothing more comforting in a colonial history of nation building than an erasure or denial of the true costs of colonial gains. The comforting narrative becomes the dominant and publicly consumed narrative.

- ^ Monkman, Lenard (17 May 2019). "Genocide against Indigenous Peoples recognized by Canadian Museum for Human Rights". Cbc.ca.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Carleton, Sean (2 October 2021). "'I don't need any more education': Senator Lynn Beyak, residential school denialism, and attacks on truth and reconciliation in Canada". Settler Colonial Studies. 11 (4): 466–486. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2021.1935574. ISSN 2201-473X.

- ^ Ballingall, Alex (6 April 2017). "Lynn Beyak calls removal from Senate committee 'a threat to freedom of speech'". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Galloway, Gloria (9 March 2017). "Conservatives disavow Tory senator's positive views of residential schools". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Mitchell (15 December 2020). "Erin O'Toole Claimed Residential School Architects Only Meant to 'Provide Education' to Indigenous Children". PressProgress. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Conrad Black: The truth about truth and reconciliation". nationalpost. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Palmater, Pamela (16 July 2021). "Manitoba Conservatives Crash and Burn with Residential School Denialism ⋆ The Breach". The Breach. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Turnbull, Ryan. "When 'good intentions' don't matter: The Indian Residential School system". The Conversation. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Justice, Daniel Heath; Carleton, Sean (25 August 2021). "Truth before reconciliation: 8 ways to identify and confront Residential School denialism". The Royal Society of Canada. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "The Dangerous Allure of Residential School Denialism | The Walrus". 4 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Cobain, Ian; Norton-Taylor, Richard (30 November 2012). "Mau Mau massacre cover-up detailed in newly-opened secret files". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ a b Murphy, Philip (17 April 2023). "It makes a good story – but the cover-up of Britain's savage treatment of the Mau Mau was exaggerated". Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Bruce Berman (1990). Control & Crisis in Colonial Kenya: The Dialectic of Domination. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85255-069-4.

- ^ Gerdziunas, Benas (17 October 2017). "Belgium's genocidal colonial legacy haunts the country's future". The Independent. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (13 May 1999). "The hidden holocaust". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (1 September 1998). "'King Leopold's Ghost': Genocide With Spin Control". New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 16 February 2014 suggested (help) - ^ Hochschild, Adam (2002). King Leopold's ghost : a story of greed, terror, and heroism in colonial Africa. Internet Archive. London : Pan. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-330-49233-1.

- ^ Bates, Stephen (13 May 1999). "The hidden holocaust". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "2008 Theodore Roosevelt-Woodrow Wilson Award Recipient | AHA". www.historians.org. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Mapping the massacres of Australia's colonial frontier". www.newcastle.edu.au. University of Newcastle. 5 July 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "How to access the 'Bringing them home' report, community guide, video and education module". HREOC. Archived from the original on 23 March 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Brennan, Frank (21 February 2008). "The history of apologies down under". Thinking Faith. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ a b Manne, Robert (18 November 2014). "In Denial, The stolen generations and the Right". Quarterly Essay. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

...the Prime Minister of Australia, John Howard, seized his opportunity. He told a commercial radio audience in Melbourne that the revelation that Lowitja O'Donoghue was not stolen was a "highly significant" fact, one, he implied, which vindicated his government's famous denial of the existence of the stolen generations and his even more famous refusal to apologize... It was the magazine Quadrant, however, under the editorship of Padraic McGuinness, that marshalled the troops and galvanised the disparate voices of opposition to Bringing them home into what amounted to a serious and effective political campaign.

- ^ Ried, James (30 March 2016). "'Invaded' not settled: UNSW rewrites history". The New Daily. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Graham, Chris (30 March 2016). "Australian university accused of 'rewriting history' over British invasion language". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Lemarchand, Rene (2011). Forgotten Genocides: Oblivion, Denial, and Memory. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8122-2263-0. JSTOR j.ctt3fhnm9.

The colonial genocide perpetrated against Aborigines produced within the colonial society a deep and enduring ambiguity about the fate of the original Aborigines and the role of colonists in generating that fate. This ambiguity consisted of a deep-seated moral unease about what had occurred and a culture of denial that was expressed in numerous ways, but most obviously in the myth of inevitable extinction.

- ^ Allam, Lorena; Evershed, Nick (3 March 2019). "The killing times: the massacres of Aboriginal people Australia must confront". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (2022). Destroying to Replace: Settler Genocides of Indigenous Peoples. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. p. xxix. ISBN 978-1-64792-054-8.

- ^ Sousa, Ashley Riley (June 2004). "'They will be hunted down like wild beasts and destroyed!': a comparative study of genocide in California and Tasmania". Journal of Genocide Research. 6 (2): 193–209. doi:10.1080/1462352042000225949. S2CID 109131060.

- ^ Baldry, Hannah; McKeon, Ailsa; McDougall, Scott (2 November 2015). "Queensland's Frontier Killing Times – Facing Up To Genocide". QUT Law Review. 15 (1). doi:10.5204/qutlr.v15i1.583.

- ^ Sunderland, Willard (2000). "The 'Colonization Question': Visions of Colonization in Late Imperial Russia". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 48 (2): 210–232. JSTOR 41050526.