Theodora (wife of Justinian I)

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (June 2023) |

| Theodora | |

|---|---|

| Augusta | |

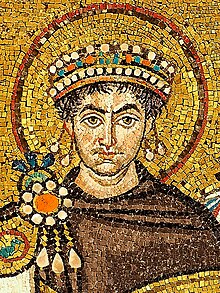

Depiction from a contemporary portrait mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna | |

| Byzantine empress | |

| Tenure | 1 April 527 – 28 June 548 |

| Born | c. 500 |

| Died | 28 June 548 (aged 48) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Justinian I |

| Dynasty | Justinian |

| Religion | Christianity (Miaphysitism) |

Theodora (/ˌθiːəˈdɔːrə/; Greek: Θεοδώρα; c. 500 – 28 June 548)[1] was a Byzantine empress through her marriage to emperor Justinian. She became empress upon Justinian's accession in 527 and was one of his chief advisers. Both she and Justinian were from humble origins. Along with her spouse, Theodora is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and in the Oriental Orthodox Church, commemorated on 14 November and 28 June respectively.

Early years

Much of Theodora's early life is unknown. The foremost source of information on her life before marrying Justinian is Procopius's Secret History, which is often regarded as slanderous.[2] According to Michael the Syrian, her birthplace was in Mabbug, Syria;[3] Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos names Theodora a native of Cyprus,[4] while the Patria, attributed to George Codinus, claims Theodora came from Paphlagonia. She was born c. AD 500.[5] Her father, Acacius, was a bear trainer of the hippodrome's Green faction in Constantinople. Her mother, whose name is not recorded, was a dancer and an actress.[6] Her parents had two more daughters, the eldest named Comito and the youngest Anastasia.[7] After her father's death, her mother remarried quickly, but the family lacked a source of income, as Acacius's position was given away due to a bribe paid to a faction official called Asterius. When Theodora was four, her mother brought her children wearing garlands into the Hippodrome and presented them as suppliants to the Green faction, but they rebuffed her efforts. Consequently, Theodora's mother approached the Blue faction.[8] The Blues took pity on their family and gave the open position of bear keeper to Theodora's stepfather, saving them from destitution.

According to Procopius' Secret History, Theodora followed her sister Comito's example from an early age and worked in a Constantinople brothel serving low and high status customers; later, she performed on stage. In his famous account of Theodora, itself based on the Secret History, Edward Gibbon wrote:

Her venal charms were abandoned to a promiscuous crowd of citizens and strangers of every rank, and of every position; the fortunate lover who had been promised a night of enjoyment, was often driven from her bed by a stronger or more wealthy favourite; and when she passed through the streets, her presence was avoided by all who wished to escape either the scandal or the temptation.[9]

According to Procopius, Theodora made a name for herself with her salacious portrayal of Leda and the Swan.[10][11] Employment as an actress at the time would have included both performing "indecent exhibitions" on stage and providing sexual services off stage. During this time, she may have met the future wife of Belisarius, Antonina, who would later become a part of the women's court led by Theodora.

The accuracy of Procopius's portrayal of Theodora's early career is unclear. Sexual promiscuity was ascribed to many female actresses and performers of the time, and the Secret History's lengthy and pornographic descriptions of Theodora's behavior are perceived as slanderous and unreliable by many modern historians. However, some contemporary authors, such as John of Ephesus, describe Theodora with clarity as having come “from the brothel." Consistent with the Christian principles of repentance and forgiveness, John wrote of her redemption as a positive tale.[12]

Later, Theodora traveled to North Africa as the concubine of a Syrian official named Hecebolus, who became the governor of the Libyan Pentapolis.[13] Procopius alleges that Theodora was badly mistreated by Hecebolus, and that their relationship dissolved after a quarrel some time after their arrival in Africa. Theodora, "destitute of the means of life,"[10] settled for a while in Alexandria, Egypt, where some historians speculate that she met Patriarch Timothy III, a Miaphysite, and converted to Miaphysite Christianity. From Alexandria, she traveled to Antioch, where she met a Blue faction dancer called Macedonia who perhaps served as an informer of Justinian; according to Procopius, Macedonia and Justinian often exchanged letters. Afterwards, Theodora returned to Constantinople. There, she met Justinian.

Justinian sought to marry Theodora, though he was prevented from doing so by a Roman law from Constantine's time that barred anyone of senatorial rank from marrying actresses. The empress Euphemia, consort of the emperor Justin, also strongly opposed the marriage. Following Euphemia's death in 524, Justin passed a new law stating that reformed actresses could marry outside of their rank if the marriage was approved by the emperor.[14] Shortly thereafter, Justinian married Theodora.[13]

Theodora had an illegitimate daughter, whose father is unknown and whose name has been lost. The same law that permitted Justinian to marry Theodora allowed Theodora's daughter to marry a relative of the late emperor Anastasius. Procopius's Secret History claimed that Theodora also had an illegitimate son called John, who arrived in Constantinople several years after Justinian and Theodora's marriage claiming to be Theodora's son.[15] According to Procopius, when Theodora learned of John's arrival and claims, she secretly had him sent away to an unknown location, and he was never heard from again. Some historians, including classics scholar James Allan Evans, believe that Procopius's account of John is unlikely to be factual because Theodora publicly acknowledged her illegitimate daughter and therefore likely would have acknowledged an illegitimate son, had one existed.[16]

Empress

When Justinian succeeded to the throne in 527, two years after the marriage, Theodora was crowned augusta and became empress of the Eastern Roman Empire. According to Procopius, she shared in his decisions, plans and political strategies, participated in state councils, and had great influence over him. Justinian once called her his "partner in my deliberations,"[17] in Novel 8.1 (AD 535), an anti-corruption legislation, where provincial officials had to take an oath to her as well as the emperor.

As Justinian's partner, Theodora shared Justinian's vision of the Byzantine Empire. His vision was straightforward – there could be no Roman Empire that didn't include Rome within its control. Since childhood, he was taught that there was one God and, therefore to him one legitimate Empire. Due to being the only Christian Emperor and Empress, they believed it was their role to duplicate the heavenly structure on Earth.[18] Being relatively young as an Emperor and Empress, compared to their recent predecessors, neither Justinian nor Theodora were content to maintaining the status quo. Their goals and projects, whether it be building new churches and public buildings or raising troops for expansive military campaigns, would require a large amount of funding. Justinian and his chief financial minister, John the Cappadocian, ruthlessly pursued additional taxes from the aristocracy who bristled at the lack of respect for their patrician status.[19]

The Nika riots

Two major party factions were at odds before, during, and after Justinian and Theodora's reign – the Blues and the Greens. Street violence between the parties was a regular event and when Justinian became emperor, he staked out a claim to drive the city to a more lawful and orderly community. These efforts were not perceived, however, as being even handed since both he and Theodora's favor were perceived as being aligned with the Blues (Justinian was believed to prefer the Blues due to their more moderate stances while Theodora's family was abandoned by the Greens after her father's death and consequently given support by the Blues as a child.) Consequently, the Greens felt isolated and frustrated.[20] During a riot between the two factions in early January 532, the urban prefect Eudaemon arrested a group of both Green and Blue felons and convicted them of murder. They were sentenced to death but two of the felons, one Blue and one Green, survived the hanging when the scaffold collapsed. Both sides appealed for mercy at the hippodrome where the public was permitted to entreat the emperor on issues. As the chariot race card hit the second to last race for the day, the two factions (typically bitter rivals) united in a chant extolling the desire of both parties for mercy as a united front. Justinian recognized the danger of these factions uniting against Theodora and himself and retreated to the palace to plan their next actions.[21]

The rioters set many public buildings on fire, and proclaimed a new emperor, Hypatius, the nephew of former emperor Anastasius I. Unable to control the mob, Justinian and his officials prepared to flee. According to Procopius, at a meeting of the government council, Theodora spoke out against leaving the palace and underlined the significance of someone who died as a ruler instead of living as an exile or in hiding, saying, "royal purple is the noblest shroud".[22]

According to Procopius, as the emperor and his counsellors were still preparing their project, Theodora reportedly interrupted them and stated:

My lords, the present occasion is too serious to allow me to follow the convention that a woman should not speak in a man's council. Those whose interests are threatened by extreme danger should think only of the wisest course of action, not of conventions. In my opinion, flight is not the right course, even if it should bring us to safety. It is impossible for a person, having been born into this world, not to die; but for one who has reigned it is intolerable to be a fugitive. May I never be deprived of this purple robe, and may I never see the day when those who meet me do not call me Empress. If you wish to save yourself, my lord, there is no difficulty. We are rich; over there is the sea, and yonder are the ships. Yet reflect for a moment whether, when you have once escaped to a place of security, you would not gladly exchange such safety for death. As for me, I agree with the adage, that "royal purple" is the noblest shroud.[23]

Her determined speech motivated them, including Justinian who had been preparing to flee. Afterwards Justinian ordered his loyal troops, led by the officers, Belisarius and Mundus, to attack the demonstrators in the Hippodrome, killing over 30,000 civilian rebels. Other reports claimed greater numbers of victims as the distance from Constantinople increased; the scholar and historian Zachariah of Mytilene estimated the dead at more than eighty thousand.[24]

Some scholars have interpreted Procopius' account as framing Justinian with the implication that he was more cowardly than his wife, that the wording of her speech was devised by Procopius. Changing the term "tyranny" to "royal purple", possibly reflecting Procopius' desire to link Theodora and Justinian to ancient tyrants.[25]

Despite his claims that he was unwillingly named emperor by the mob, Hypatius was also put to death by Justinian. In one source, this came at Theodora's insistence.[26]

Later life

Following the Nika revolt, Justinian and Theodora rebuilt Constantinople, including aqueducts, bridges and more than twenty-five churches, the most famous of which is Hagia Sophia. Justinian and Theodora also recognized the danger of allowing the level of dissent to grow throughout the empire as a result of the actions of their reign that impacted the common people. Although, they soon felt secure enough to reinstate the two ministers that were dismissed to appease the rebels; John the Cappadocian as financial minister, Tribonian as the primary legal minister. The couple monitored their administration's actions more carefully to ensure that their activities were more reasonable in their impact on the common citizenry. Justinian and Theodora retained a distaste for the aristocrats that had attempted to unseat them. In retaliation against their disloyalty, the 19 senators that participated in the attempted Nika coup had their estates destroyed, and their bodies were dumped in the sea. Those who remained were left to deal with the aggressive taxation and other wealth capture schemes that John the Cappadocian hatched to continue funding Justinian and Theodora's aggressive rebuilding plans.[28]

Theodora was said to have been interested in court ceremony. According to Procopius, the Imperial couple made all senators, including patricians, prostrate themselves before them whenever they entered their presence, and made it clear that their relations with the civil militia were those of masters and slaves:

Not even the government officials could approach the Empress without expending much time and effort. They were treated like servants and kept waiting in a small, stuffy room for an endless time. After many days, some of them might at last be summoned, but going into her presence in great fear, they very quickly departed. They simply showed their respect by lying face down and touching the instep of each of her feet with their lips; there was no opportunity to speak or to make any request unless she told them to do so. The government officials had sunk into a slavish condition, and she was their slave-instructor.[citation needed]

They also supervised the magistrates to reduce bureaucratic corruption.[citation needed]

The praetorian prefect Peter Barsymes was Theodora's close ally. John the Cappadocian, Justinian's chief tax collector, she identified as her enemy, because of his independent and great influence, and was brought down by a plot devised by Theodora and Antonina. She engaged in matchmaking, forming a network of alliances between new and old powers, represented by Emperor Anastasius' family and the pre-existing nobility combined with the new monarchy of Justinian's family. According to Secret History, she attempted to marry her grandson Anastasius to Joannina, Belisarius' and Antonina's daughter and heiress, against her parents' will, which was rejected at first yet the couple would eventually marry. The marriages of her sister Comito to general Sittas and her niece Sophia to Justinian's nephew Justin II, who would succeed to the throne, are suspected to have been engineered by Theodora.

She gave reception and sent letters and gifts to Persian and foreign ambassadors and the sister of Khosrow I.[29]

She was involved in helping underprivileged women, sometimes "buying girls who had been sold into prostitution, freeing them, and providing for their future."[30] She created a convent on the Asian side of the Dardanelles called the Metanoia (Repentance), where the ex-prostitutes could support themselves.[13] Procopius' Secret History maintained that instead of preventing forced prostitution (as in Buildings 1.9.3ff), Theodora is said to have 'rounded up' 500 prostitutes, confining them to a convent. They sought to escape 'the unwelcome transformation' by leaping over the walls (SH 17). On the other hand, chronicler John Malalas who wrote positively about the court, declared she "freed the girls from the yoke of their wretched slavery."[31]

Justinian and Theodora's legislations also expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership, instituted the death penalty for rape, forbade exposure of unwanted infants, gave mothers some guardianship rights over their children, and forbade the killing of a wife who committed adultery. Procopius, in Wars, mentioned that she was naturally inclined to assist women in misfortune, and according to Secret History she was accused of unfairly championing the wives' causes moreso when they were charged with adultery (SH 17). The code of Justinian only allowed women to seek a divorce from their husbands due to either abuse or a wife catching their husband in obvious adultery. Regardless, either cause demanded that women seeking a divorce provide clear evidence of their claims.[32]

Procopius describes Theodora's as causing women to “become morally depraved” due to her and Justinian's legal actions.[33]

Religious policy

Saint Theodora | |

|---|---|

Empress Theodora and attendants (mosaic from Basilica of San Vitale, 6th century) | |

| Empress | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople modern day Istanbul, Turkey |

| Feast | 14 November in the Eastern Orthodox Church, 28 June in the Syriac Orthodox Church |

| Attributes | Imperial Vestment |

Since Justinian was not the recognized head of any of the sects of the Christian church, his focus was on reducing and, where possible, eliminating friction between the various Christian sects and the Empire. His perspective was that as the Christian emperor, he should be in harmony with the head(s) of The Church. Similarly, with Justinian a Chalcedonian and Theodora professing Miaphysite beliefs or at least sympathetic with the Monophysite cause, Justinian worked to heal the schism that divided the Constantinople church, from the Roman church. He sought a united Church that would “partner” with the one Emperor (himself). The Emperor would manage human affairs and the priesthood would manage the divine affairs of God. Since the Emperor was accountable to the law, Justinian made sure that the law recognized the Emperor as being the law incarnate – with universal authority of divine origin. Consequently, he used the law to micromanage the implementation of religion through laws aimed at its very execution.[34]

Theodora worked against her husband's support of Chalcedonian Christianity in the ongoing struggle for the predominance of each faction.[35] As a result, she was accused of fostering heresy and thus undermined the unity of Christendom. However, Procopius and Evagrius Scholasticus suggested instead that Justinian and Theodora were merely pretending to be opposed to each other.

In spite of Justinian being Chalcedonian, Theodora founded a Miaphysite monastery in Sykae and provided shelter in the palace for Miaphysite leaders who faced opposition from the majority of Chalcedonian Christians, like Severus and Anthimus. Anthimus had been appointed Patriarch of Constantinople under her influence, and after the excommunication order he was hidden in Theodora's quarters for twelve years, until her death. When the Chalcedonian Patriarch Ephraim provoked a violent revolt in Antioch, eight Miaphysite bishops were invited to Constantinople and Theodora welcomed them and housed them in the Hormisdas Palace adjoining the Great Palace, which had been Justinian and Theodora's own dwelling before they became Emperor and Empress.

In Egypt, when Timothy III died, Theodora enlisted the help of Dioscoros, the Augustal Prefect, and Aristomachos the duke of Egypt, to facilitate the enthronement of a disciple of Severus, Theodosius, thereby outmaneuvering her husband, who had intended a Chalcedonian successor. Pope Theodosius I of Alexandria, even with the help of imperial troops, could not hold his ground in Alexandria against Justinian's Chalcedonian followers and he was exiled by Justinian along with 300 Miaphysites into the fortress of Delcus in Thrace.

When Pope Silverius refused Theodora's demand that he remove the anathema of Pope Agapetus I from Patriarch Anthimus, she sent Belisarius instructions to find a pretext to remove Silverius. When this was accomplished, Pope Vigilius was appointed in his stead.

In Nobatae, south of Egypt, the inhabitants were converted to Miaphysite Christianity about 540. Justinian had been determined that they be converted to the Chalcedonian faith and Theodora equally determined that they should be Miaphysites. Justinian made arrangements for Chalcedonian missionaries from Thebaid to go with presents to Silko, the king of the Nobatae. On hearing this, Theodora prepared her own missionaries and wrote to the Duke of Thebaid that he should delay her husband's embassy, so that the Miaphysite missionaries would arrive first. The duke was canny enough to thwart the easy going Justinian instead of the unforgiving Theodora. He saw to it that the Chalcedonian missionaries were delayed and when they eventually reached Silko, they were sent away. The Nobatae had then already adopted the Miaphysite creed of Theodosius.

Death

Theodora's death is recorded by Victor of Tonnena, with the cause uncertain but the Greek terms used are often translated as "cancer". The date was 28 June 548 at the age of 48,[36] although other sources report that she died at 51.[37] Later accounts frequently attribute the death to specifically breast cancer, although it was not identified as such in the original report, in which the use of the term "cancer" probably referred to a more general "suppurating ulcer or malignant tumor".[36] Her body was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. During a procession in 559, Justinian visited and lit candles for her tomb.[38]

Historiography

The main historical sources for her life are the works of her contemporary Procopius. Procopius was a member of the staff of Belisarius, a field marshal for Justinian, who is perhaps the best-known officer of Justinian's officers largely because of Procopius's writings.[39] The historian offered three different portrayals of the Empress. The Wars of Justinian, largely completed in 545, paints a picture of a courageous woman who helped save Justinian's attempt at the throne.

Later, he wrote the Secret History. The work has sometimes been interpreted as representing a deep disillusionment with the Emperor Justinian, the empress, and even his patron Belisarius. Justinian is depicted as cruel, venal, prodigal, and incompetent; as for Theodora, the reader is given a detailed portrayal of an openly sexual woman, along with many shrewish and negative portrayals.

Procopius' Buildings of Justinian, written probably after Secret History, is a panegyric that paints Justinian and Theodora as a pious couple and presents particularly flattering portrayals of them. Besides her piety, her beauty is also praised. It is important to note, however, that Theodora had already died when the work was published, meanwhile Justinian was still alive and most likely commissioned the work.[40]

Her contemporary John of Ephesus writes about Theodora in his Lives of the Eastern Saints and mentions an illegitimate daughter.[41] Theophanes the Confessor mentions some familial relations of Theodora to figures not mentioned by Procopius. Victor Tonnennensis notes her familial relation to the next empress, Sophia.

Michael the Syrian, the Chronicle of 1234 and Bar-Hebraeus place her origin in the city of Daman, near Kallinikos, Syria. They make an alternate account compared to Procopius by making Theodora the daughter of a priest, trained in the pious practices of Miaphysitism since birth. These are late Miaphysite sources. The Miaphysites have a tendency to regard Theodora as one of their own. Their account is also an alternative to what is told by the contemporary John of Ephesus.[42] Many modern scholars prefer Procopius' account.[41]

Critiques of Procopius

Numerous historians have emerged in recent decades pointing out that Procopius is not necessarily a reliable source on which to base our common understanding of Theodora and her historical impact.

Procopius was believed to be aligned with many of the senatorial rank that disagreed with the changes and policies that Justinian and Theodora imposed upon the empire. Procopius asserts in the Secret History (12.12-14) that many in the senatorial class were being "strangled" by tax collectors due to Justinian's (and Theodora's) policy of collecting and retaining the attractive properties and furniture of the wealthy, while "generously" giving back properties that had high taxes to their original owners.[43] At one point, Procopius even compares Justinian's rule to the bubonic plague (6.22-23), arguing that the plague was a better option, since half the population escaped unscathed - unlike the impact of Justinian's rule.[44]

In the Secret History, Procopius criticizes Justinian's and Theodora's rule as the antithesis of the rule of "good" emperors and empresses. His portrayal of their emotional balance and power is significantly different. Justinian was even of temperament, "approachable and kindly" – even while ordering the confiscation of people's property or their destruction. Conversely, Theodora was described as irrational and driven by her anger, often by minor affronts or insults. For example, Procopius describes two separate incidents where she accuses men of having sexual relations with other men publicly in the judicial system. This was considered an inappropriate forum for persons of standing and, in Procopius's narrative, unappreciated by the people of Constantinople. When one of the accusations is ruled as unsubstantiated, Procopius writes that the entire city celebrated.[45]

One researcher suggested that Procopius's writings in the Secret History amount to an apocryphal tale in the dangers of “the rule of women”. Procopius's perspective as a conservative intellectual was that women, with their wily vices, served to vanquish men's otherwise virtuous leadership instincts. Procopius details two examples of Theodora's engagement in the Byzantine Empire's foreign policy that supports his perspective. First, Theodora is quoted in a letter to the Persian ambassador declaring that Emperor Justinian would do nothing without her consent. The Persian king used this as an example to his nobles of a failed state since no “real state could exist that was governed by a woman.” Similarly, the Gothic king Theodahad expressed in a letter to Theodora that confirmed that “you exhort me to bring first to your attention anything I decide to ask from the triumphal prince, your husband.” Even the Emperor himself is quoted before issuing a decree that he had discussed it with “our most august consort whom God has given us.” All of these examples offend Procopius's sense of propriety. It wasn't the fact that women couldn't lead an empire – Procopius believed that only women demonstrating masculine virtues and strengths were appropriate as leaders. The strength of Theodora was not hers; it was the lack of strength demonstrated by Justinian that created the impression of strength by Theodora.[46]

The definition of “feminine” behavior in the sixth century as used by Procopius is not the way in which modern writers would use it. “Feminine” behavior in the sixth century would be described as “intriguing”, “interfering”, and the like according to researcher Averil Cameron. Procopius found Theodora's efforts to assist “repentant” prostitutes as less the actions of a benefactress, but instead her further attempts to interfere with the status quo that he found objectionable. This is also why he includes her speech during the Nika insurrection where she interferes with the actions of the men as they contemplate escaping the rioters. Procopius's intent in describing that scene is to demonstrate that Theodora is unable to stay in her appropriate role.[47] At his core, he was a preserver of the social order. Dr. Henning Börm, Chair of Ancient History at the University of Rostock in Germany, described it to Michael Edward Stewart as a “social hierarchy: people stood over animals, freeman stood over slaves, men stood over eunuchs, and men stood over women. Whenever Procopius denounces the alleged breach of these rules, he simply follows the rules of historiography."[48]

Although Procopius as a contemporary historian demonstrates areas of clear bias, his aggrandized tales and retelling of salacious rumors (compared alongside other historians of the era) provide a glimpse into the changing values and norms of the time period, rather than a straightforward biographical study of Theodora's life and character.[16] For example, the portrayal of Justinian and Theodora as demons in the Secret History reflects a common belief system held by the people during this time period. Events unexplainable by rational means were either a product of divine providence or the result of evil demons. When Procopius was unable to explain the actions of the Emperor and Empress according to his beliefs, he fell back on the principle of outside influences being the only likely explanation.[49]

Perhaps describing Procopius as a historian is incorrect from the perspective of Averil Cameron, a researcher. In her view, Procopius is more aptly described as a reporter. He focuses on events and their details far more than analyzing motives and causes. Consequently, his portrayals lack nuance; they harshly describe events from a palette of black and white. His rigidity and inability to embrace change make him a suspect voice when pursuing a deeper understanding of how and why events occurred as they did.[50] This may also explain why Procopius in his writings is significantly different in his characterization of day-to-day life compared to the accounts of other contemporary authors. While other writers describe the daily theological battles between the different Christian sects and the efforts of the government to align and subdue them, Procopius remains almost silent on these topics. He maintains an intense and political focus on his writing that precludes a balanced and holistic perspective. This intensity results in his portrayal of Justinian and Theodora as near caricatures. By over exaggerating their faults and ignoring their successes, the reader is compelled to see them as villain or hero.[51]

Lasting influence

The Miaphysites believed her influence on Justinian to be so strong that after her death, when he worked to bring harmony between the Miaphysites and the Chalcedonian Christians in the Empire and kept his promise to protect her little community of Miaphysite refugees in the Hormisdas Palace, the Miaphysites suspected Theodora's memory to be the driving factor. Theodora provided much political support for the ministry of Jacob Baradaeus, and apparently personal friendship as well. Diehl attributes the modern existence of Jacobite Christianity equally to Baradaeus and to Theodora.[52]

Olbia in Cyrenaica renamed itself Theodorias after Theodora. (It was a common event that ancient cities renamed themselves to honor an Emperor or Empress.) The city, now called Qasr Libya, is known for its splendid sixth-century mosaics.

Theodora and Justinian are represented in mosaics that exist to this day in the Basilica of San Vitale of Ravenna, Italy, which were completed a year before her death after 547 when the Byzantines retook the city. She is depicted in full imperial garb, endowed with jewels befitting her role as empress. Her cloak is embroidered with imagery of the three kings bearing their gifts for the Christ child, symbolizing a connection with her and Justinian bringing gifts to the church. In this case, she is shown bearing a communion chalice. In addition to the religious tone of these mosaics, other mosaics depict Theodora and Justinian receiving the vanquished kings of the Goths and Vandals as prisoners of war, surrounded by the cheering Roman Senate. The Emperor and Empress are recognized in both victory and in generosity in these large-scale public works.[53]

Media portrayals

Art

- The artwork The Dinner Party features a place setting for Theodora.[54]

Books

- The Homecoming. Arthur Conan Doyle (1909). A short story of Theodora's son's surprise visit to Constantinople.[55]

- Count Belisarius. Robert Graves (1938). A historical novel by the author of I, Claudius, which features Theodora as a character.

- In one of the episodes of Hendrik Willem van Loon's 1942 fantasy novel Van Loon's Lives

- Theodora and the Emperor. Harold Lamb (1952). Historical novel that focuses on the life of Theodora, her relationship with Justinian, and her many accomplishments as Empress.

- The Glittering Horn: Secret Memoirs of the Court of Justinian. Pierson Dixon (1958). A historical novel about the court of Justinian with Theodora playing a central part.

- The Female. Paul Wellman (1953). The rise of Theodora from prostitute to empress.

- Theodora von Byzanz. Ein Mädchen aus dem Volk wird Kaiserin (1957). Friedhelm Volbach (under the pseudonym Rudolph Fürstenberg). German historical novel.[56]

- The Bearkeeper's Daughter. Gillian Bradshaw (1987). A young man out of Theodora's past arrives at the palace, seeking the truth of certain statements made to him by his dying father.

- The Sarantine Mosaic. Guy Gavriel Kay (1998). Historical fantasy modelled on the Byzantium empire and the story of Justinian and Theodora.

- In the historical mystery novel One for Sorrow by Mary Reed/Eric Mayer, Theodora is one of the suspects in the murder case investigated by John, the Lord Chamberlain.

- Immortal. Christopher Golden and Nancy Holden (1999). A Buffy the Vampire Slayer novel that mentions Theodora working with the vampire Veronique towards immortality in 543 AD.

- Theodora: Actress, Empress, Whore. Stella Duffy (2010). A historical novel, about Theodora's years up until she became empress.

- The Purple Shroud. Stella Duffy (2012). A historical novel, about Theodora's years as empress.

- The Secret History Stephanie Thornton (2020). Theodora's life story rendered into a novel.

Film

- Teodora imperatrice di Bisanzio (Short, 1909) aka Theodora, Empress of Byzantium. Directed by Ernesto Maria Pasquali.

- Teodora, imperatrice di Bisanzio (1954) aka Theodora, Slave Empress. Directed by Riccardo Freda. Theodora played by Gianna Maria Canale.

- Kampf um Rom (1968) directed by Robert Siodmak, Sergiu Nicolaescu and Andrew Marton. In this movie she is played by Sylva Koscina.

- Primary Russia (1985) directed by Gennady Vasilyev. Theodora played by Margarita Terekhova

Theater

- Theodora, a Drama (1884), a play by Victorien Sardou.

Video games

- Theodora is the leader for the Byzantines in the video game Civilization III, Civilization V in its Gods and Kings expansion, and an alternate leader in Civilization VI's Leader Pass.

- Theodora gives missions to Belisarius, the main character in the Last Roman DLC for Total War: Attila.

- Theodora is a playable character in the Mobile/PC Game Rise of Kingdoms.

Music

- The progressive rock band Big Big Train sings of Theodora herself, and the mosaics of Theodora and Justinian in Ravenna, in the song "Theodora in Green and Gold" on their 2019 album Grand Tour.

- George Frideric Handel's oratorio "Theodora" does not refer to the empress.

Citations

- ^ Karagianni 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Foss, C. (2002). "THE EMPRESS THEODORA". Byzantion. 72 (1): 141–176. ISSN 0378-2506.

- ^ James Allan Evans (2011). The Power Game in Byzantium: Antonina and the Empress Theodora. A&C Black. p. 9. ISBN 978-1441120403.

- ^ Michael Grant. From Rome to Byzantium: The Fifth Century A.D., Routledge, p. 132.

- ^ Giorgio Ravegnani (2016). Salerno Editrice (ed.). Teodora. p. 26. ISBN 978-88-6973-149-5.

- ^ The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire 2 Volume Set., J. R. Martindale, 1992 Cambridge University Press, p. 1240.

- ^ Garland, p. 11.

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2002). The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-292-79895-4. OCLC 55675917.

- ^ E, Gibbon (1776). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: 1776–1788. UK: Strahan & Cadell, London. pp. Chapter xl. ISBN 9780140433951.

- ^ a b Procopius, Secret History 9.

- ^ Claudine M. Dauphin (1996). "Brothels, Baths and Babes: Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land". Classics Ireland. 3: 47–72. doi:10.2307/25528291. JSTOR 25528291. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century. London: Routledge. pp. 77–78. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ a b c Bryce 1911, p. 761.

- ^ Grau, Sergi; Febrer, Oriol (2020-08-01). "Procopius on Theodora: ancient and new biographical patterns". Byzantinische Zeitschrift (in German). 113 (3): 769–788. doi:10.1515/bz-2020-0034. ISSN 1868-9027.

- ^ Garland, Lynda (1999). Byzantine Empresses. Routledge. p. 14. doi:10.4324/9780203024812. ISBN 978-1-134-75639-1.

- ^ a b Evans, James Allan (2002). The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-292-79895-4. OCLC 55675917.

- ^ Diehl, Charles (1963). Byzantine Empresses. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ^ Brownworth, Lars (2009). Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization. New York: Crown Publishers. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-307-40795-5. OCLC 297147191.

- ^ Brownworth, Lars (2009). Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization. New York: Crown Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-307-40795-5. OCLC 297147191.

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2002). The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-292-79895-4. OCLC 55675917.

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2002). The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 0-292-79895-4. OCLC 55675917.

- ^ Safire, William, ed, Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1992, p. 37 [ISBN missing]

- ^ William Safire, Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History, Rosetta Books

- ^ Hamilton, F. J.; Brooks, E. W. (1899). The Syriac Chronicle known as that of Zachariah of Mitylene. London: Methuen and Co. p. 81.

- ^ Moorhead, John (1994). Justinian. London. p. 47.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) [ISBN missing] - ^ Diehl, ibid.

- ^ "Discussion :: Last Statues of Antiquity". laststatues.classics.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Brownworth, Lars (2009). Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization. New York: Crown Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-307-40795-5. OCLC 297147191.

- ^ Procopius, Secret History 30.24; Malalas, Chronicle 18.467

- ^ Anderson & Zinsser, Bonnie & Judith (1988). A History of Their Own: Women in Europe Vol 1. New York: Harper & Row. p. 48.[ISBN missing]

- ^ John Malalas, The Chronicle of John Malalas, 18.440.14–441.7

- ^ Grau, Sergi; Febrer, Oriol (1 August 2020). "Procopius on Theodora: ancient and new biographical patterns". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 113 (3): 783. doi:10.1515/bz-2020-0034. ISSN 1868-9027. S2CID 222004516.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the Sixth Century. London: Routledge. pp. 81–82. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ Angold, Michael (2001). Byzantium: The Bridge From Antiquity to the Middle Ages. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-312-28429-2. OCLC 47100855.

- ^ "Theodora – Byzantine Empress". About.com. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ a b Harding, Fred (2007). Breast Cancer. ISBN 978-0955422102.

- ^ Anderson & Zinsser, Bonnie & Judith (1988). A History of Their Own: Women in Europe, Vol. 1. New York: Harper & Row. p. 48.

- ^ Constantine Porphyrogennetos, The Book of Ceremonies, 1, Appendix 14.

- ^ Evans, James Allen (2002). The Empress Theodora. University of Texas Press. pp. ix. doi:10.7560/721050. ISBN 978-0-292-79895-3.

- ^ "Roman Emperors – DIR Theodora". roman-emperors.org.

- ^ a b Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, vol. 3, ed. J. Martindale. 1992.

- ^ Garland, p. 13.

- ^ Grau, Sergi; Febrer, Oriol (1 August 2020). "Procopius on Theodora: ancient and new biographical patterns". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 113 (3): 779–780. doi:10.1515/bz-2020-0034. ISSN 1868-9027. S2CID 222004516.

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2002). The Empress Theodora. University of Texas Press. pp. x. doi:10.7560/721050. ISBN 978-0-292-79895-3.

- ^ Georgiou, Andriani (2019), Constantinou, Stavroula; Meyer, Mati (eds.), "Empresses in Byzantine Society: Justifiably Angry or Simply Angry?", Emotions and Gender in Byzantine Culture, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 123–126, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96038-8_5, ISBN 978-3-319-96037-1, S2CID 149788509, retrieved 19 December 2022

- ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2004). Procopius of Caesarea: Tyranny, History, and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity. University of Pennsylvania. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-0-8122-0241-0. OCLC 956784628.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ Stewart, Michael Edward (2020). Masculinity, identity, and power politics in the age of Justinian : a study of Procopius. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University. p. 173. ISBN 978-90-485-4025-9. OCLC 1154764213.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century. London: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century. London: Routledge. p. 241. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1996). Procopius and the sixth century. London: Routledge. pp. 227–229. ISBN 0-415-14294-6. OCLC 36048226.

- ^ Diehl, ibid., p. 184.

- ^ Garland, Lynda (1999). Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204. London: Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 0-203-15951-9. OCLC 49851647.

- ^ Place Settings. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.

- ^ "The Home-Coming - The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia". www.arthur-conan-doyle.com. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ Library of Congress Copyright Office (1959). Catalog of Copyright Entries. Third Series: 1958: January-June. Copyright Office, Library of Congress. p. 665. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

General and cited references

- Hans-Georg Beck: Kaiserin Theodora und Prokop: der Historiker und sein Opfer. Munich 1986, ISBN 3-492-05221-5.

- Henning Börm: Procopius, his predecessors, and the genesis of the Anecdota: Antimonarchic discourse in late antique historiography. In: Henning Börm (ed.): Antimonarchic discourse in Antiquity. Stuttgart 2015, pp. 305–346.

- Bryce, James (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 761–762.

- James A. S. Evans: The empress Theodora. Partner of Justinian. Austin 2002.

- James A. S. Evans: The Power Game in Byzantium. Antonina and the Empress Theodora. London 2011.

- Lynda Garland: Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527–1204. London 1999.

- Hartmut Leppin: Theodora und Iustinian. In: Hildegard Temporini-Gräfin Vitzthum (ed.): Die Kaiserinnen Roms. Von Livia bis Theodora. Munich 2002, pp. 437–481.

- Mischa Meier: "Zur Funktion der Theodora-Rede im Geschichtswerk Prokops (BP 1,24,33-37)", Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 147 (2004), pp. 88ff.

- David Potter: Theodora. Actress, Empress, Saint. Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-974076-5.

- Karagianni, Alexandra (2013). "Female Monarchs in the Medieval Byzantine Court: Prejudice, Disbelief and Calumnies". In Woodacre, Elena (ed.). Queenship in the Mediterranean: Negotiating the Role of the Queen in the Medieval and Early Modern Eras. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 22. ISBN 978-1137362827.

- Procopius, The Secret History at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Procopius, The Secret History at LacusCurtius