Gazetteer

A gazetteer is a geographical dictionary[1][2][3] or directory used in conjunction with a map or atlas.[4][5] It typically contains information concerning the geographical makeup, social statistics and physical features of a country, region, or continent. Content of a gazetteer can include a subject's location, dimensions of peaks and waterways, population, gross domestic product and literacy rate. This information is generally divided into topics with entries listed in alphabetical order.

Ancient Greek gazetteers are known to have existed since the Hellenistic era. The first known Chinese gazetteer was released by the first century, and with the age of print media in China by the ninth century, the Chinese gentry became invested in producing gazetteers for their local areas as a source of information as well as local pride. The geographer Stephanus of Byzantium wrote a geographical dictionary (which currently has missing parts) in the sixth century which influenced later European compilers. Modern gazetteers can be found in reference sections of most libraries as well as on the internet.

Etymology

[edit]The Oxford English Dictionary defines a "gazetteer" as a "geographical index or dictionary".[6] It includes as an example a work by the British historian Laurence Echard (d. 1730) in 1693 that bore the title "The Gazetteer's: or Newsman's Interpreter: Being a Geographical Index".[6] Echard wrote that the title "Gazetteer's" was suggested to him by a "very eminent person" whose name he chose not to disclose.[6] For Part II of this work published in 1704, Echard referred to the book simply as "the Gazeteer". This marked the introduction of the word "gazetteer" into the English language.[6] Historian Robert C. White suggests that the "very eminent person" written of by Echard was his colleague Edmund Bohun, and chose not to mention Bohun because he became associated with the Jacobite movement.[6]

Since the 18th century, the word "gazetteer" has been used interchangeably to define either its traditional meaning (i.e., a geographical dictionary or directory) or a daily newspaper, such as the London Gazetteer.[7][8]

Types and organization

[edit]Gazetteers are often categorized by the type, and scope, of the information presented. World gazetteers usually consist of an alphabetical listing of countries, with pertinent statistics for each one, with some gazetteers listing information on individual cities, towns, villages, and other settlements of varying sizes. Short-form gazetteers, often used in conjunction with computer mapping and GIS systems, may simply contain a list of place-names together with their locations in latitude and longitude or other spatial referencing systems (e.g., British National Grid reference). Short-form gazetteers appear as a place–name index in the rear of major published atlases. Descriptive gazetteers may include lengthy textual descriptions of the places they contain, including explanation of industries, government, geography, together with historical perspectives, maps and/or photographs. Thematic gazetteers list places or geographical features by theme; for example fishing ports, nuclear power stations, or historic buildings. Their common element is that the geographical location is an important attribute of the features listed.

Gazetteer editors gather facts and other information from official government reports, the census, chambers of commerce, together with numerous other sources, and organise these in digest form.

History

[edit]Western world

[edit]Hellenistic and Greco-Roman eras

[edit]

In his journal article "Alexander and the Ganges" (1923), the 20th-century historian W.W. Tarn calls a list and description of satrapies of Alexander's Empire written between 324 and 323 BC as an ancient gazetteer.[9] Tarn notes that the document is dated no later than June 323 BC, since it features Babylon as not yet partitioned by Alexander's generals.[10] It was revised by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus in the 1st century BC.[10] In the 1st century BC, Dionysius of Halicarnassus mentioned the chronicle-type format of the writing of the logographers in the age before the founder of the Greek historiographic tradition, Herodotus (i.e., before the 480s BC), saying "they did not write connected accounts but instead broke them up according to peoples and cities, treating each separately".[11] Historian Truesdell S. Brown asserts that what Dionysius describes in this quote about the logographers should be categorized not as a true "history" but rather as a gazetteer.[11] While discussing the Greek conception of the river delta in ancient Greek literature, Francis Celoria notes that both Ptolemy and Pausanias of the 2nd century AD provided gazetteer information on geographical terms.[12]

Perhaps predating Greek gazetteers were those made in ancient Egypt. Although she does not specifically label the document as a gazetteer, Penelope Wilson (Department of Archaeology, Durham University) describes an ancient Egyptian papyrus found at the site of Tanis, Egypt (a city founded during the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt), which provides the following for each administrative area of Egypt at the time:[13]

...the name of a nome capital, its sacred barque, its sacred tree, its cemetery, the date of its festival, the names of forbidden objects, the local god, land, and lake of the city. This interesting codification of data, probably made by a priest, is paralleled by very similar editions of data on the temple walls at Edfu, for example.[13]

Medieval and early modern eras

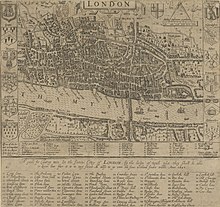

[edit]The Domesday Book initiated by William I of England in 1086 was a government survey on all the administrative counties of England; it was used to assess the properties of farmsteads and landholders in order to tax them sufficiently. In the survey, numerous English castles were listed; scholars debate on exactly how many were actually referenced in the book.[14] However, the Domesday Book does detail the fact that out of 3,558 registered houses destroyed in 112 different boroughs listed, 410 of these destroyed houses were the direct result of castle construction and expansion.[15] In 1316 the Nomina Villarum survey was initiated by Edward II of England; it was essentially a list of all the administrative subdivisions throughout England which could be utilized by the state in order to assess how much military troops could be conscripted and summoned from each region.[16] The Speculum Britanniae (1596) of the Tudor era English cartographer and topographer John Norden (1548–1625) had an alphabetical list of places throughout England with headings showing their administrative hundreds and referenced to attached maps.[17] Englishman John Speed's Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine published in 1611 provided gazetteers for counties throughout England, which included illustrative maps, short local histories, a list of administrative hundreds, an index of parishes, and the coordinates of longitude and latitude for county towns.[18] Starting in 1662, the Hearth Tax Returns with attached maps of local areas were compiled by individual parishes throughout England while a duplicate of their records were sent to the central government offices of the Exchequer.[16] To supplement his "new large Map of England" from 1677, the English cartographer John Adams compiled the extensive gazetteer "Index Villaris" in 1680 that had some 24,000 places listed with geographical coordinates coinciding with the map.[17] The "Geographical Dictionary" of Edmund Bohun was published in London in 1688, comprising 806 pages with some 8,500 entries.[19] In his work, Edmund Bohun attributed the first known Western geographical dictionary to geographer Stephanus of Byzantium (fl. 6th century) while also noting influence in his work from the Thesaurus Geographicus (1587) by the Belgian cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598), but stated that Ortelius' work dealt largely with ancient geography and not up-to-date information.[19] Only fragments of Stephanus' geographical work Ethnica (Εθνικά) have survived and were first examined by the Italian printer Aldus Manutius in his work of 1502.

The Italian monk Phillippus Ferrarius (d. 1626) published his geographical dictionary "Epitome Geographicus in Quattuor Libros Divisum" in the Swiss city of Zürich in 1605.[20] He divided this work into overhead topics of cities, rivers, mountains, and lakes and swamps.[20] All placenames, given in Latin, were arranged in alphabetical order for each overhead division by geographic type;.[20] A year after his death, his "Lexicon Geographicum" was published, which contained more than 9,000 different entries for geographic places.[20] This was an improvement over Ortelius' work, since it included modern placenames and places discovered since the time of Ortelius.[20]

Pierre Duval (1618–1683), a nephew of the French cartographer Nicolas Sanson, wrote various geographical dictionaries. These include a dictionary on the abbeys of France, a dictionary on ancient sites of the Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans with their modern equivalent names, and a work published in Paris in 1651 that was both the first universal and vernacular geographical dictionary of Europe.[19] With the gradual expansion of Laurence Echard's (d. 1730) gazetteer of 1693, it too became a universal geographical dictionary that was translated into Spanish in 1750, into French in 1809, and into Italian in 1810.[21]

Following the American Revolutionary War, United States clergyman and historian Jeremy Belknap and Postmaster General Ebenezer Hazard intended to create the first post-revolutionary geographical works and gazetteers, but they were anticipated by the clergyman and geographer Jedidiah Morse with his Geography Made Easy in 1784.[22] However, Morse was unable to finish the gazetteer in time for his 1784 geography and postponed it.[23] Yet his delay to publish it lasted too long, as it was Joseph Scott in 1795 who published the first post-revolutionary American gazetteer, his Gazetteer of the United States.[23] With the aid of Noah Webster and Rev. Samuel Austin, Morse finally published his gazetteer The American Universal Geography in 1797.[24] However, Morse's gazetteer did not receive distinction by literary critics, as gazetteers were deemed as belonging to a lower literary class.[25] The reviewer of Joseph Scott's 1795 gazetteer commented that it was "little more than medleys of politics, history and miscellaneous remarks on the manners, languages and arts of different nations, arranged in the order in which the territories stand on the map".[25] Nevertheless, in 1802 Morse followed up his original work by co-publishing A New Gazetteer of the Eastern Continent with Rev. Elijah Parish, the latter of whom Ralph H. Brown asserts did the "lion's share of the work in compiling it".[26]

Modern era

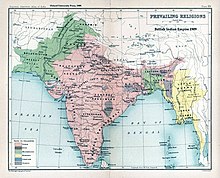

[edit]Gazetteers became widely popular in Britain in the 19th century, with publishers such as Fullarton, Mackenzie, Chambers and W & A. K. Johnston, many of whom were Scottish, meeting public demand for information on an expanding Empire. This British tradition continues in the electronic age with innovations such as the National Land and Property Gazetteer, the text-based Gazetteer for Scotland, and the new (2008) National Gazetteer (for Scotland), formerly known as the Definitive National Address – Scotland National Gazetteer. In addition to local or regional gazetteers, there have also been comprehensive world gazetteers published; an early example would be the 1912 world gazetteer published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.[27] There are also interregional gazetteers with a specific focus, such as the gazetteer of the Swedish atlas "Das Bästas Bilbok" (1969), a road atlas and guide for Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark.[28]

East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]

In Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) China, the Yuejue Shu (越絕書) written in 52 AD is considered by modern sinologists and historians to be the prototype of the gazetteer (Chinese: difangzhi), as it contained essays on a wide variety of subjects including changes in territorial division, the founding of cities, local products, and customs.[29] However, the first gazetteer proper is considered to be the Chronicles of Huayang by Chang Qu 常璩. There are over 8,000 gazetteers of pre-modern China that have survived.[30][31][32] Gazetteers became more common in the Song dynasty (960–1279), yet the bulk of surviving gazetteers were written during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty (1644–1912).[30] Modern scholar Liu Weiyi notes that just under 400 gazetteers were compiled in the era between the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 and the Tang dynasty (618–907).[33] Gazetteers from this era focused on boundaries and territory, place names, mountains and rivers, ancient sites, local products, local myths and legends, customs, botany, topography, and locations of palaces, streets, temples, etc.[34] By the Tang dynasty the gazetteer became much more geographically specific, with a broad amount of content arranged topically; for example, there would be individual sections devoted to local astronomy, schools, dikes, canals, post stations, altars, local deities, temples, tombs, etc.[35] By the Song dynasty it became more common for gazetteers to provide biographies of local celebrities, accounts of elite local families, bibliographies, and literary anthologies of poems and essays dedicated to famous local spots.[33][36] Song gazetteers also made lists and descriptions of city walls, gate names, wards and markets, districts, population size, and residences of former prefects.[37]

In 610 after the Sui dynasty (581–618) united a politically divided China, Emperor Yang of Sui had all the empire's commanderies prepare gazetteers called 'maps and treatises' (Chinese: tujing) so that a vast amount of updated textual and visual information on local roads, rivers, canals, and landmarks could be utilized by the central government to maintain control and provide better security.[38][39] Although the earliest extant Chinese maps date to the 4th century BC,[40] and tujing since the Qin (221–206 BC) or Han dynasties, this was the first known instance in China when the textual information of tujing became the primary element over the drawn illustrations.[41] This Sui dynasty process of providing maps and visual aids in written gazetteers—as well as the submitting of gazetteers with illustrative maps by local administrations to the central government—was continued in every subsequent Chinese dynasty.[42]

Historian James M. Hargett states that by the time of the Song dynasty, gazetteers became far more geared towards serving the current political, administrative, and military concerns than in gazetteers of previous eras, while there were many more gazetteers compiled on the local and national levels than in previous eras.[43] Emperor Taizu of Song ordered Lu Duosun and a team of cartographers and scholars in 971 to initiate the compilation of a huge atlas and nationwide gazetteer that covered the whole of China proper,[39] which comprised approximately 1,200 counties and 300 prefectures.[44] This project was completed in 1010 by a team of scholars under Song Zhun, who presented it in 1,566 chapters to the throne of Emperor Zhenzong.[39] This Sui dynasty process of infrequently collecting tujing or "map guides" continued, but it would be enhanced by the matured literary genre of fangzhi or "treatise on a place" of the Song dynasty.[44] Although Zheng Qiao of the 12th century did not notice the fangzhi while writing his encyclopedic Tongzhi including monographs to geography and cities, others such as the bibliographer Chen Zhensun of the 13th century were listing gazetteers instead of the map guides in their works.[44] The main differences between the fangzhi and the tujing was that the former was a product of "local initiative, not a central command" according to Peter K. Bol, and were usually ten, twenty, or even fifty chapters in length compared to the average four chapters for map guides.[45] Furthermore, the fangzhi were almost always printed because they were intended for a large reading audience, whereas tujing were exclusive records read by the local officials who drafted them and the central government officials who collected them.[45] Although most Song gazetteers credited local officials as the authors, already in the Song there were bibliographers who noted that non-official literati were asked to compose these works or did so on their own behalf.[46] By the 16th century—during the Ming dynasty—local gazetteers were commonly composed due to local decision-making rather than a central government mandate.[47] Historian Peter K. Bol states that local gazetteers composed in this manner were the result of increased domestic and international trade that facilitated greater local wealth throughout China.[47] Historian R. H. Britnell writes of gazetteers in Ming China, "by the sixteenth century, for a county or monastery not to have a gazetteer was regarded as evidence that the place was inconsequential".[48]

While working in the Department of Arms, the Tang dynasty cartographer Jia Dan (730–805) and his colleagues would acquire information from foreign envoys about their respective homelands, and from these interrogations would produce maps supplemented by textual information.[49] Even within China, ethnographic information on ethnic minorities of non-Han peoples were often described in the local histories and gazetteers of provinces such as Guizhou during the Ming and Qing dynasties.[50] As the Qing dynasty pushed further with its troops and government authorities into areas of Guizhou that were uninhabited and not administered by the Qing government, the official gazetteers of the region would be revised to include the newly drawn-up districts and non-Han ethnic groups (mostly Miao peoples) therein.[50] While the late Ming dynasty officials who compiled the information on the ethnic groups of Guizhou offered scanty details about them in their gazetteers (perhaps due to their lack of contact with these peoples), the later Qing dynasty gazetteers often provided a much more comprehensive analysis.[51] By 1673 the Guizhou gazetteers featured different written entries for the various Miao peoples of the region.[51] Historian Laura Holsteter writes on the woodblock print illustrations of Miao peoples in the Guizhou gazeteer, stating "the 1692 version of the Kangxi era gazetteer show a refinement in the quality of the illustrations by comparison to 1673".[52]

Historian Timothy Brook states that Ming dynasty gazetteers demonstrate a shift in the attitudes of Chinese gentry towards the traditionally lower merchant class.[53] As time went on, the gentry solicited funds from merchants to build and repair schools, print scholarly books, build Chinese pagodas on auspicious sites, and other things that were needed by the gentry and scholar-officials in order to succeed.[53] Hence, the gentry figures composing the gazetteers in the latter half of the Ming period spoke favorably of merchants, whereas before they were rarely mentioned.[53] Brook and other modern sinologist historians also examine and consult the local Ming gazetteers to compare population info with the contemporary central government records, which often provided dubious population figures that did not reflect the actually larger population size of China during the time.[54]

Although better known for his work on the Gujin Tushu Jicheng encyclopedia, the early-to-mid Qing scholar Jiang Tingxi aided other scholars in the compilation of the "Daqing Yitongzhi" ('Gazetteer of the Qing Empire').[55] This was provided with a preface in 1744 (more than a decade after Jiang's death), revised in 1764, and reprinted in 1849.[55]

The Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci created the first comprehensive world map in the Chinese language in the early 17th century,[56] while comprehensive world gazetteers were later translated into Chinese by Europeans. The Christian missionary William Muirhead (1822–1900), who lived in Shanghai during the late Qing period, published the gazetteer "Dili quanzhi", which was reprinted in Japan in 1859.[57] Divided into fifteen volumes, this work covered Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Pacific Ocean Archipelagos, and was sub-divided further into sections on geography, topography, water masses, atmosphere, biology, anthropology, and historical geography.[58] Chinese maritime trade gazetteers mentioned a slew of different countries that came to trade in China, such as United States vessels docking at Canton in the "Yuehaiguanzhi" ('Gazetteer of the Maritime Customs of Guangdong') published in 1839 (reprinted in 1935).[59] The Chinese language gazetteer Haiguo Tuzhi ('Illustrated Gazetteer of the Sea Kingdoms') by Wei Yuan in 1844 (with material influenced by the "Sizhou zhi" of Lin Zexu)[60] was printed in Japan two decades later 1854.[61] This work was popular in Japan not for its geographical knowledge, but for its analysis of potential defensive military strategy in the face of European imperialism and the Qing's recent defeat in the First Opium War due to European artillery and gunboats.[61]

Continuing an old tradition of fangzhi, the Republic of China had gazetteers composed and created national standards for them in 1929, updating these in 1946.[62] The printing of gazetteers was revived in 1956 under Mao Zedong and again in the 1980s, after the reforms of the Deng era to replace the people's communes with traditional townships.[63] The difangzhi effort under Mao yielded little results (only 10 of the 250 designated counties ended up publishing a gazetteer), while the writing of difangzhi was interrupted during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), trumped by the village and family histories which were more appropriate for the theme of class struggle.[64][65] A Li Baiyu of Shanxi forwarded a letter to the CCP Propaganda Department on May 1, 1979, which urged for the revival of difangzhi.[64] This proposal was sponsored by Hu Yaobang in June 1979 while Hu Qiaomu of the CCP Politburo lent his support for the idea in April 1980.[64] The first issue of a modern national journal of difangzhi was issued by January 1981.[64]

Korea

[edit]In Korea, scholars based their gazetteers largely on the Chinese model.[66] Like Chinese gazetteers, there were national, provincial, and local prefecture Korean gazetteers which featured geographic information, demographic data, locations of bridges, schools, temples, tombs, fortresses, pavilions, and other landmarks, cultural customs, local products, resident clan names, and short biographies on well-known people.[67][68][69] In an example of the latter, the 1530 edition of "Sinjŭng tongguk yŏji sŭngnam" ('New Edition of the Korean National Gazetteer') gave a brief statement about Pak Yŏn (1378–1458), noting his successful career in the civil service, his exceptional filiality, his brilliance in music theory, and his praisable efforts in systematizing ritual music for Sejong's court.[67] King Sejong established the Joseon dynasty's first national gazetteer in 1432, called the "Sinch'an p'aldo" ('Newly Compiled Geographic Treatise on the Eight Circuits').[70] With additional material and correction of mistakes, the title of this gazetteer was revised in 1454 as the "Sejong Sillok chiriji" ('King Sejong's Treatise on Geography'), updated in 1531 under the title "Sinjŭng tongguk yŏji sŭngnam" ('Augmented Survey of the Geography of Korea'),[70] and enlarged in 1612.[69] The Joseon Koreans also created international gazetteers. The "Yojisongnam" gazetteer compiled from 1451 to 1500 provides a small description for 369 different foreign countries known to Joseon Korea in the 15th century.[66]

Japan

[edit]In Japan, there were also local gazetteers in pre-modern times, called fudoki.[71] Japanese gazetteers preserved historical and legendary accounts of various regions. For example, the Nara-period (710–794) provincial gazetteer Harima no kuni fūdoki of Harima Province provides a story of an alleged visit by Emperor Ōjin in the 3rd century while on an imperial hunting expedition.[72] Local Japanese gazetteers could also be found in later periods such as the Edo period.[73] Gazetteers were often composed by the request of wealthy patrons; for example, six scholars in the service of the daimyō of the Ikeda household published the Biyō kokushi gazetteer for several counties in 1737.[74] World gazetteers were written by the Japanese in the 19th century, such as the Kon'yo zushiki ("Annotated Maps of the World") published by Mitsukuri Shōgo in 1845, the Hakkō tsūshi ("Comprehensive Gazetteer of the Entire World") by Mitsukuri Genpo in 1856, and the Bankoku zushi ("Illustrated Gazetteer of the Nations of the World"), which was written by an Englishman named Colton, translated by Sawa Ginjirō, and printed by Tezuka Ritsu in 1862.[57] Despite the ambitious title, the work by Genpo only covered Yōroppa bu ("Section on Europe") while the planned section for Asia was not published.[57] In 1979 the 50 volume gazeteer Nihon rekishi chimei taikei ("Japanese Historical Place Names") series was launched[75] and it is currently also available online with "200,000 headings with detailed explanations of [each] place name".[76]

South Asia

[edit]In pre-modern India, local gazetteers were written. For example, Muhnot Nainsi wrote a gazetteer (Nainsi ri Khyat and Marwar rai Pargana ri Vigat) for the Marwar region in the 17th century.[77] B. S. Baliga writes that the history of the gazetteer in Tamil Nadu can be traced back to the classical corpus of Sangam literature, dated 200 BC to 300 AD.[78] Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, the vizier to Akbar the Great of the Mughal Empire, wrote the Ain-e-Akbari, which included a gazetteer with valuable information on India's population in the 16th century.[79]

Muslim world

[edit]The pre-modern Islamic world produced gazetteers. Cartographers of the Safavid dynasty of Iran made gazetteers of local areas.[80]

List of gazetteers

[edit]Worldwide

[edit]Antarctica

[edit]Australia

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]- National Land and Property Gazetteer

- National Street Gazetteer

- The Gazetteer for Scotland

- Imperial Gazetteer of Scotland

- Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales

India

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Gazetteer". Macmillan Dictionary. Macmillan. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Webster's dictionary and Roget's thesaurus. Paradise Press Inc. 2006. p. 68. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Webster's New Dictionary. Promotional Sales Books. 1997. p. 126. ISBN 1577233603. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Aurousseau, 61.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. Gazetteer, n3. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e White, 658.

- ^ Thomas, 623–636.

- ^ Asquith, 703–724.

- ^ Tarn, 93–94.

- ^ a b Tarn, 94.

- ^ a b Brown (1954), 837.

- ^ Celoria, 387.

- ^ a b Wilson (2003), 98.

- ^ Harfield, 372.

- ^ Harfield, 373–374.

- ^ a b Ravenhill, 425.

- ^ a b Ravenhill, 424.

- ^ Ravenhill, 426.

- ^ a b c White, 657.

- ^ a b c d e White, 656.

- ^ White, 659.

- ^ Brown (1941), 153–154.

- ^ a b Brown (1941), 189.

- ^ Brown (1941), 189–190.

- ^ a b Brown (1941), 190.

- ^ Brown (1941), 194.

- ^ Aurousseau, 66.

- ^ Murphy, 113.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 406.

- ^ a b Hargett (1996), 405.

- ^ Thogersen & Clausen, 162.

- ^ Bol, 37–38.

- ^ a b Hargett (1996), 407.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 408.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 411.

- ^ Bol, 41.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 414.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 409–410.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 3, 518.

- ^ Hsu, 90.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 409.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 410.

- ^ Hargett (1996), 412.

- ^ a b c Bol, 44.

- ^ a b Bol, 46.

- ^ Bol, 47.

- ^ a b Bol, 38.

- ^ Britnell, 237.

- ^ Schafer, 26–27.

- ^ a b Hostetler, 633.

- ^ a b Hostetler, 634.

- ^ Hostetler, 637–638.

- ^ a b c Brook, 6–7, 73, 90–93, 129–130, 151.

- ^ Brook, 28, 94–96, 267.

- ^ a b Fairbank & Teng, 211.

- ^ Wong, 44.

- ^ a b c Masuda, 18.

- ^ Masuda, 18–19.

- ^ Fairbank & Teng, 215.

- ^ Masuda, 32.

- ^ a b Masuda, 23–24.

- ^ Vermeer 440.

- ^ Thogersen & Clausen, 161–162.

- ^ a b c d Thogersen & Clausen, 163.

- ^ Vermeer, 440–443.

- ^ a b McCune, 326.

- ^ a b Provine, 8.

- ^ Lewis, 225–226.

- ^ a b Pratt & Rutt, 423.

- ^ a b Lewis, 225.

- ^ Miller, 279.

- ^ Taryō, 178.

- ^ Levine, 78.

- ^ Hall, 211.

- ^ Yasuko Makino,"Heibonsha" (entry), The Oxford Companion to the Book, oxfordreference.com. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Nihon rekishi chimei taikei (日本歴史地名大系) = Japanese Historical Place Names, ku.edu. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Gole, 102.

- ^ Baliga, 255.

- ^ Floor & Clawson, 347–348.

- ^ King, 79.

References

[edit]- Asquith, Ivon (2009). "Advertising and the Press in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 1790–1821". The Historical Journal. 18 (4): 703–724. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00008864. JSTOR 2638512. S2CID 140975585.

- Aurousseau, M. (1945). "On Lists of Words and Lists of Names". The Geographical Journal. 105 (1/2): 61–67. doi:10.2307/1789547. JSTOR 1789547.

- Baliga, B.S. (2002). Madras District Gazetteers. Chennai: Superintendent, Government Press.

- Bol, Peter K. (2001). "The Rise of Local History: History, Geography, and Culture in Southern Song and Yuan Wuzhou". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 61 (1): 37–76. doi:10.2307/3558587. JSTOR 3558587.

- Britnell, R.H. (1997). Pragmatic Literacy, East and West, 1200–1330. Woodbridge, Rochester: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-695-9.

- Brook, Timothy. (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0 (Paperback).

- Brown, Ralph H. (1941). "The American Geographies of Jedidiah Morse". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 31 (3): 145–217. doi:10.1080/00045604109357224. ISSN 0004-5608.

- Brown, Truesdell S. (1954). "Herodotus and His Profession". The American Historical Review. 59 (4): 829–843. doi:10.2307/1845119. JSTOR 1845119.

- Celoria, Francis (1966). "Delta as a Geographical Concept in Greek Literature". Isis. 57 (3): 385–388. doi:10.1086/350146. S2CID 143811840.

- Fairbank, J. K.; Teng, S. Y. (1941). "On The Ch'ing Tributary System". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 6 (2): 135. doi:10.2307/2718006. JSTOR 2718006.

- Floor, Willem; Clawson, Patrick (2001). "Safavid Iran's Search for Silver and Gold". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 32 (3): 345–368. doi:10.1017/S0020743800021139. JSTOR 259513. S2CID 162418783.

- Gole, Susan (2008). "Size as a measure of importance in Indian cartography". Imago Mundi. 42 (1): 99–105. doi:10.1080/03085699008592695. JSTOR 1151051.

- Hall, John Whitney (1957). "Materials for the Study of Local History in Japan: Pre-Meiji Daimyō Records". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 20 (1/2): 187–212. doi:10.2307/2718525. JSTOR 2718525.

- Harfield, C.G. (1991). "A Hand-List of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book". The English Historical Review. 106 (419): 371–392. doi:10.1093/ehr/CVI.CCCCXIX.371. JSTOR 573107.

- Hargett, James M. (1996). "Song Dynasty Local Gazetteers and Their Place in The History of Difangzhi Writing". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 56 (2): 405–442. doi:10.2307/2719404. JSTOR 2719404.

- Hostetler, Laura (2008). "Qing Connections to the Early Modern World: Ethnography and Cartography in Eighteenth-Century China". Modern Asian Studies. 34 (3): 623–662. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00003772. JSTOR 313143. S2CID 147656944.

- Hsu, Mei‐Ling (2008). "The Qin maps: A clue to later Chinese cartographic development". Imago Mundi. 45 (1): 90–100. doi:10.1080/03085699308592766. JSTOR 1151164.

- King, David A. (2008). "Two Iranian world maps for finding the direction and distance to Mecca". Imago Mundi. 49 (1): 62–82. doi:10.1080/03085699708592859. JSTOR 1151334.

- Levine, Gregory P. (2001). "Switching Sites and Identities: The Founder's Statue at the Buddhist Temple Korin'in". The Art Bulletin. 83 (1): 72–104. doi:10.2307/3177191. JSTOR 3177191.

- Lewis, James B. (2003). Frontier Contact Between Choson Korea and Tokugawa Japan. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1301-8.

- Masuda, Wataru. (2000). Japan and China: Mutual Representations in the Modern Era. Translated by Joshua A. Fogel. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22840-6.

- McCune, Shannon (1946). "Maps of Korea". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 5 (3): 326–329. doi:10.2307/2049053. JSTOR 2049053. S2CID 134509348.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1967). "Old Japanese Phonology and the Korean-Japanese Relationship". Language. 43 (1): 278–302. doi:10.2307/411398. JSTOR 411398.

- Murphy, Mary (1974). "Atlases of the Eastern Hemisphere: A Summary Survey". Geographical Review. 64 (1): 111–139. doi:10.2307/213796. JSTOR 213796.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Pratt, Keith L. and Richard Rutt. (1999). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Richmond: Routledge; Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-0463-9.

- Provine, Robert C. (2000). "Investigating a Musical Biography in Korea: The Theorist/Musicologist Pak Yon (1378–1458)". Yearbook for Traditional Music. 32: 1–15. doi:10.2307/3185240. JSTOR 3185240. S2CID 191402230.

- Ravenhill, William (1978). "John Adams, His Map of England, Its Projection, and His Index Villaris of 1680". The Geographical Journal. 144 (3): 424–437. doi:10.2307/634819. JSTOR 634819.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T’ang Exotics. University of California Press. Berkeley and Los Angeles. 1st paperback edition: 1985. ISBN 0-520-05462-8.

- Tarn, W. W. (2013). "Alexander and the Ganges". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 43 (2): 93–101. doi:10.2307/625798. JSTOR 625798. S2CID 164111602.

- Taryō, Ōbayashi; Taryo, Obayashi (1984). "Japanese Myths of Descent from Heaven and Their Korean Parallels". Asian Folklore Studies. 43 (2): 171. doi:10.2307/1178007. JSTOR 1178007.

- Thomas, Peter D. G. (1959). "The Beginning of Parliamentary Reporting in Newspapers, 1768–1774". The English Historical Review. LXXIV (293): 623–636. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXIV.293.623. JSTOR 558885.

- Thogersen, Stig; Clausen, Soren (1992). "New Reflections in the Mirror: Local Chinese Gazetteers (Difangzhi) in the 1980s". The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs. 27 (27): 161–184. doi:10.2307/2950031. JSTOR 2950031. S2CID 130833332.

- Vermeer, Eduard B. (2016). "New County Histories". Modern China. 18 (4): 438–467. doi:10.1177/009770049201800403. JSTOR 189355. S2CID 144007701.

- White, Robert C. (1968). "Early Geographical Dictionaries". Geographical Review. 58 (4): 652–659. doi:10.2307/212687. JSTOR 212687.

- Wilson, Penelope. (2003). Sacred Signs: Hieroglyphs in Ancient Egypt. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280299-2.

- Wong, H.C. (1963). "China's Opposition to Western Science during Late Ming and Early Ch'ing". Isis. 54 (1): 29–49. doi:10.1086/349663. JSTOR 228727. S2CID 144136313.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Gazetteers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gazetteers at Wikimedia Commons