Habsburg Spain

| History of Spain |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

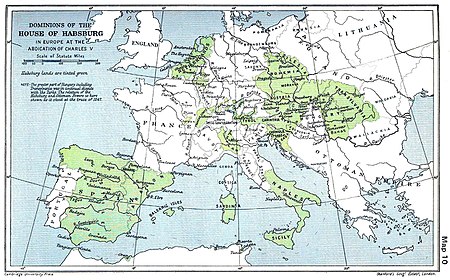

During the reign of Emperor Charles V (Carlos I of Spain), who ascended the thrones of the kingdoms of Spain after the death of his grandfather Ferdinand, Habsburg Spain controlled territory ranging from Philippines to the Netherlands, and was, for a time, Europe's greatest power. For this reason, this period of Spanish history has also been referred to as the "Age of Expansion". Although usually associated with its role in the history of Central Europe, the Habsburg family extended its realm into Spain from 1516 to 1700, where the Habsburg senior line reigned for that period. Under Habsburg rule, Spain reached the zenith of its influence and power, but also began its slow decline.

Spain's 16th century maritime supremacy was demonstrated by the victory over the Ottomans at Lepanto in 1571 (which was symbolically important to the Spanish), and then after the setback of the Spanish Armada in 1588, in a series of victories against England in the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604. However during the middle decades of the 17th century Habsburg Spain's maritime power went into a long decline with mounting defeats against the United Provinces and then England; that by the 1660s it was struggling grimly to defend its overseas possessions from pirates and privateers. On land Habsburg Spain became embroiled in the vast Thirty Years' War, and in the second half of the 17th century the Spanish were defeated by the French, led by King Louis XIV. Habsburg rule came to an end in Spain with the death in 1700 of Charles II which resulted in the War of the Spanish Succession.

The Habsburg years were also a Spanish Golden Age of cultural efflorescence. Some of the outstanding figures of the period were Diego Velázquez, El Greco, Miguel de Cervantes, and Pedro Calderón de la Barca.

The beginnings of the empire (1504–1521)

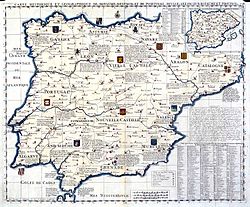

Spain as we know it today did not come into being until the death of Charles II and with him the extinction of the Habsburg Dynasty, and the ascension of Philip V and the inauguration of the Bourbon Dynasty and its reforms. The political area referred to as Spain was, in fact, a confederacy comprised of several ancient, individual kingdoms—Catalonia, Valencia, Andalucia, Castile, Leon, Aragon, Galicia, Asturias, Vizcaya, Guipozcoa, Roussillon, and Navarre. The push to drive the Moors from Spain, its capstone being the conquest of Granada, united (somewhat) these many and fiercely independent kingdoms. The subsequent marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469 was brought to pass in hopes of maintaining and strengthening these alliances, which it did to a degree.

In 1504, Queen Isabella died, and although Ferdinand tried to maintain his position over Castile in the wake of her death, the Castilian Cortes Generales (the royal court of Spain) chose to crown Isabella's daughter Joanna queen. Her husband Philip was the Habsburg son of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I and Mary of Burgundy and simultaneously became king-consort Philip I of Castile. Shortly thereafter Joanna began to lapse into insanity. In 1506, Philip assumed the regency on her behalf, but he died later that year under mysterious circumstances, possibly poisoned by his father-in-law [1]. Since their oldest son Charles was only six, the Cortes reluctantly allowed Joanna's father Ferdinand to rule the country as the regent of Joanna and Charles.

Spain was now united under a single ruler, Ferdinand II of Aragon. As sole monarch, Ferdinand adopted a more aggressive policy than he had as Isabella's husband, enlarging Spain's sphere of influence in Italy, strengthening it against France. As ruler of Aragon, Ferdinand had been involved in the struggle against France and Venice for control of Italy; these conflicts became the center of Ferdinand's foreign policy as king. Ferdinand's first investment of Spanish forces came in the War of the League of Cambrai against Venice, where the Spanish soldiers distinguished themselves on the field alongside their French allies at the Battle of Agnadello (1509). Only a year later, Ferdinand joined the Holy League against France, seeing a chance at taking both Naples - to which he held a dynastic claim - and Navarra, which was claimed through his marriage to Germaine de Foix. The war was less of a success than that against Venice, and in 1516, France agreed to a truce that left Milan under French control and recognized Spanish hegemony in northern Navarre. Unfortunately Ferdinand died later that year.

Ferdinand's death led to the ascension of young Charles to the throne as Charles I of Castile and Aragon, effectively founding the monarchy of Spain. His Spanish inheritance included all the Spanish possessions in the New World and around the Mediterranean. Upon the death of his Habsburg father in 1506, Charles had inherited the Netherlands and Franche-Comté, growing up in Flanders. In 1519, with the death of his paternal grandfather Maximilian I, Charles inherited the Habsburg territories in Germany, and was duly elected Emperor Charles V that year. His mother remained as titular queen of Castile until her death 1555, but due to her health, Charles (titled there as king also) exercised all true power. At that point, Emperor and King Charles was the most powerful man in Christendom.

The accumulation of so much power to one man and one dynasty greatly concerned the king of France, Francis I, who found himself surrounded by Habsburg territories. In 1521, Francis invaded the Spanish possessions in Italy and inaugurated a second round of Franco-Spanish conflict. The war was a disaster for France, which suffered defeats at Biccoca (1522), Pavia (1525, at which Francis was captured), and Landriano (1529) before Francis relented and abandoned Milan to Spain once more.

An emperor and a king (1521–1556)

Charles’s victory at the Battle of Pavia, 1525, surprised many Italians and Germans and elicited concerns that Charles would endeavor to gain ever greater power. Pope Clement VII switched sides and now joined forces with France and prominent Italian states against the Habsburg Emperor, in the War of the League of Cognac. In 1527, due to Charles' inability to pay them sufficiently his armies in Northern Italy mutineed and sacked Rome itself for loot, forcing Clement, and succeeding popes, to be considerably more prudent in their dealings with secular authorities: in 1533, Clement’s refusal to annul Henry VIII of England’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon (Charles' aunt) was a direct consequence of his unwillingness to offend the emperor and have his capital perhaps sacked a second time. The Peace of Barcelona, signed between Charles and the pope in 1529, established a more cordial relationship between the two leaders that effectively named Spain as the protector of the Catholic cause and recognized Charles as king of Lombardy in return for Spanish intervention in overthrowing the rebellious Florentine Republic.

In 1543, Francis I, king of France, announced his unprecedented alliance with the Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, by occupying the Spanish-controlled city of Nice in cooperation with Turkish forces. Henry VIII of England, who bore a greater grudge against France than he held against the Emperor for standing in the way of his divorce, joined Charles in his invasion of France. Although the Spanish army was soundly defeated at the Battle of Ceresole, in Savoy, Henry fared better, and France was forced to accept terms. The Austrians, led by Charles’s younger brother Ferdinand, continued to fight the Ottomans in the east. With France defeated, Charles went to take care of an older problem: the Schmalkaldic League.

The Protestant Reformation had begun in Germany in 1517. Charles, through his position as Holy Roman Emperor, his important holdings along Germany's frontiers, and his close relationship with his Habsburg relatives in Austria, had a vested interest in maintaining the stability of the Holy Roman Empire. The Peasants' War had broken out in Germany in 1524 and ravaged the country until it was brutally put down in 1526. Charles, even as far away from Germany as he was, was committed to keeping order. Since the Peasants' War, the Protestants had organized themselves into a defensive league to protect themselves from Emperor Charles. Under the protection of the Schmalkaldic League, the Protestant states had committed a number of outrages in the eyes of the Catholic Church— the confiscation of some ecclesiastical territories, among other things— and had defied the authority of the Emperor.

Perhaps more importantly to the strategy of the Spanish king, the League had allied itself with the French, and efforts in Germany to undermine the League had been rebuffed. Francis’ defeat in 1544 led to the annulment of the alliance with the Protestants, and Charles took advantage of the opportunity. He first tried the path of negotiation at the Council of Trent in 1545, but the Protestant leadership, feeling betrayed by the stance taken by the Catholics at the council, went to war, led by the Saxon elector Maurice. In response, Charles invaded Germany at the head of a mixed Dutch-Spanish army, hoping to restore the Imperial authority. The emperor personally inflicted a decisive defeat on the Protestants at the historic Battle of Mühlberg in 1547. In 1555, Charles signed the Peace of Augsburg with the Protestant states and restored stability in Germany on his principle of cuius regio, eius religio, a position unpopular with the Spanish and Italian clergy. Charles' involvement in Germany would establish a role for Spain as protector of the Catholic Habsburg cause in the Holy Roman Empire; the precedent would seven decades later lead to involvement in the war that would decisively end Spain's status as Europe's leading power.

In 1526, Charles married Infanta Isabella, the sister of John III of Portugal. In 1556, Charles abdicated from his positions, giving his Spanish empire to his only surviving son, Philip II of Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire to his brother, Ferdinand. Charles retired to the monastery of Yuste (Extremadura, Spain), where he is thought to have had a nervous breakdown, and died in 1558.

St. Quentin to Lepanto (1556–1571)

Spain was not yet at peace, as the aggressive Henry II of France came to the throne in 1547 and immediately renewed the conflict with Spain. Charles' successor, Philip II, aggressively conducted the war against France, crushing a French army at the Battle of St. Quentin in Picardy in 1557 and defeating Henry again at the Battle of Gravelines the following year. The Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, signed in 1559, permanently recognized Spanish claims in Italy. In the celebrations that followed the treaty, Henry was killed by a stray splinter from a lance. France was stricken for the next thirty years by civil war and unrest (see French Wars of Religion) and was unable to effectively compete with Spain and the Habsburgs in the European power struggle. Freed from any serious French opposition, Spain saw the apogee of its might and territorial reach in the period 1559–1643.

Charles and his successors, while they may have been most comfortable with and fond of Spain, regarded it as just another part of their empire, rather than nurturing and developing it, as France, England, and the Netherlands might have in their countries. Achieving the political goals of the Habsburg dynasty – which primarily meant undermining the power of France, maintaining Catholic Habsburg hegemony in Germany, and suppressing the Ottoman Empire – was more important to the Habsburg rulers than the welfare of Spain. This emphasis would contribute to the decline of Spanish imperial power.

The Spanish Empire had grown substantially since the days of Ferdinand and Isabella. The Aztec and Inca Empires were conquered during Charles' reign, from 1519 to 1521 and 1540 to 1558, respectively. Spanish settlements were established in the New World: Florida was colonized in the 1560s, Buenos Aires was established in 1536, and New Granada (modern Colombia) was colonized in the 1530s. Manila, in the Philippines, was established in 1572. The Spanish Empire abroad became the source of Spanish wealth and power in Europe, but contributed also to inflation. Instead of fueling the Spanish economy, American silver made Spain dependent on foreign sources of raw materials and manufactured goods. The economic and social revolutions taking place in France and England had no counterparts in Spain.

After Spain's victory over France in 1559 and the beginning of France's religious wars, Philip's ambitions grew. The Ottoman Empire had long menaced the fringes of the Habsburg dominions in Austria and northwest Africa, and in response Ferdinand and Isabella had sent expeditions to North Africa, capturing Melilla in 1497 and Oran in 1509. Charles had preferred to combat the Ottomans through a considerably more maritime strategy, hampering Ottoman landings on the Venetian territories in the Eastern Mediterranean. Only in response to raids on the eastern coast of Spain did Charles personally lead attacks against holdings in North Africa (1545). In 1565, the Spanish defeated an Ottoman landing on the strategically vital island of Malta, defended by the Knights of St. John. The death of Suleiman the Magnificent the following year and his succession by the less capable Selim the Sot emboldened Philip, who resolved to carry the war to the Ottoman homelands. In 1571, a mixed naval expedition led by Charles' illegitimate son Don John of Austria annihilated the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto, in one of the most decisive battles in naval history. The battle ended the threat of Ottoman naval hegemony in the Mediterranean.

The troubled king (1571–1598)

The time for rejoicing in Madrid was short-lived. In 1566, Calvinist-led riots in the Spanish Netherlands (roughly equal to modern-day Netherlands and Belgium, inherited by Philip from Charles and his Burgundian forebearers) prompted the Duke of Alva to conduct a military expedition to restore order. In 1568, William the Silent led a failed attempt to drive the tyrannical Alva from the Netherlands. This attempt is generally considered to signal the start of the Eighty Years' War that ended with the independence of the United Provinces. The Spanish, who derived a great deal of wealth from the Netherlands and particularly from the vital port of Antwerp, were committed to restoring order and maintaining their hold on the provinces. In 1572, a band of rebel Dutch privateers known as the watergeuzen ("Sea Beggars") seized a number of Dutch coastal towns, proclaimed their support for William and denounced the Spanish leadership.

For Spain, the war was a creeping disaster. In 1574, the Spanish army under Luis de Requeséns was repulsed from the Siege of Leiden after the Dutch destroyed the dykes that held back the North Sea from the low-lying provinces. In 1576, faced with the costs of his 80,000-man army of occupation in the Netherlands and the massive fleet that had won at Lepanto, Philip was forced to accept bankruptcy. The army in the Netherlands mutinied not long after, seizing Antwerp and looting the southern Netherlands, prompting several cities in the previously peaceful southern provinces to join the rebellion. The Spanish chose the route of negotiation, and pacified most of the southern provinces again with the Union of Arras in 1579.

The Arras agreement required all Spanish troops to leave these lands. In 1580, this gave king Philip the opportunity to strengthen his position when the last male member of the Portuguese royal family, Cardinal Henry of Portugal, died. Philip asserted a weak claim to the Portuguese throne and in June sent an army under the leadership of the Duke of Alba to Lisbon to assure his succession. Though the duke and the Spanish occupation, however, were little more popular in Lisbon than in Rotterdam, the combined Spanish and Portuguese empires placed into Philip’s hands most of the explored New World along with a vast trading empire in Africa and Asia.

To keep Portugal under control required an extensive occupation force, and Spain was still reeling from the 1576 bankruptcy. In 1584, William the Silent was assassinated by a half-deranged Catholic, and the death of the popular Dutch resistance leader was expected to bring an end to the war; it did not. In 1586, Queen Elizabeth I of England, supported the Protestant cause in the Netherlands and France, and Sir Francis Drake launched attacks against Spanish merchants in the Caribbean and the Pacific Ocean, along with a particularly aggressive attack on the port of Cadiz. In 1588, hoping to put a stop to Elizabeth’s meddling, Philip sent the Spanish Armada to attack England. Of the 130 ships sent on the mission, only half returned safely to Spain, and some 20,000 troops perished. Some were victims of English ships, but most were victims of severe weather encountered on their return trip. The disastrous outcome, resulting from a combination of the unfavorable weather and a good deal of luck for the English under Lord Howard of Effingham, resulted in a complete overhaul of the Spanish navy's ships, weapons and tactics. It struck back at English attacks and with the help of a bungled English counter attack (English Armada) quickly recovered its preeminent position which it maintained for another half of a century. Spain also provided support to a gruelling Irish war which drained England of resources and also raided English coastal towns. However, now the Spanish Habsburgs had yet another powerful enemy with which to contend, forcing Spain to maintain an even stronger, more expensive navy, atop of massive expenditures for its armies in its many scattered territories.

Spain had invested itself in the religious warfare in France after Henry II’s death. In 1589, Henry III, the last of the Valois lineage, died at the walls of Paris. His successor, Henry IV of Navarre, the first Bourbon king of France, was a man of great ability, winning key victories against the Catholic League at Arques (1589) and Ivry (1590). Committed to stopping Henry from becoming King of France, the Spanish divided their army in the Netherlands and invaded France in 1590.

"God is Spanish" (1596–1626)

Faced with wars against England, France, and the Netherlands, each led by extraordinarily capable leaders, already-bankrupted Spain was outmatched. Struggling with continuing piracy against its shipping in the Atlantic and the disruption of its vital gold shipments from the New World, Spain was forced to admit bankruptcy again in 1596. The Spanish attempted to extricate themselves from the several conflicts they were involved in, first signing the Treaty of Vervins with France in 1598, recognizing Henry IV (since 1593 a Catholic) as king of France, and restoring many of the stipulations of the previous Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis. A treaty with England was agreed upon in 1604, following the accession of the more tractable Stuart King James I.

Peace with England and France implied that Spain could focus her energies on restoring her rule to the Dutch provinces. The Dutch, led by Maurice of Nassau, the son of William the Silent and perhaps the greatest strategist of his time, had succeeded in taking a number of border cities since 1590, including the fortress of Breda. Following the peace with England, the new Spanish commander Ambrosio Spinola pressed hard against the Dutch. Spinola, a general of abilities to match Maurice, was prevented from conquering the Netherlands only by Spain’s renewed bankruptcy in 1607. Faced with ruined finances, in 1609, the Twelve Years' Truce was signed between Spain and the United Provinces.

Spain made a fair recovery during the truce, ordering her finances and doing much to restore her prestige and stability in the run-up to the last truly great war in which she would play as a leading power. In the Netherlands, the rule of Philip II's daughter, Isabella Clara Eugenia and her husband, Archduke Albert, restored stability to the southern Netherlands and pacified anti-Spanish sentiments in the area. Philip II’s successor, Philip III, was a man of limited ability uninterested in politics, preferring to allow others to take care of the details. His chief minister was the capable Duke of Lerma. Lerma, a financial wizard, succeeded in turning Spain’s account books around and made himself one of the richest men in Europe with a fortune of some 44 million thalers, Lerma’s personal success attracted enemies and well-founded allegations of corruption; in 1618, the king replaced him with Don Balthasar de Zúñiga. While the Duke of Lerma (and to a large extent Philip III) had been disinterested in the affairs of their ally, Austria, Zúñiga was a veteran ambassador to Vienna and believed that the key to restraining the resurgent French and eliminating the Dutch was a closer alliance with Habsburg Austria.

In 1618, beginning with the Defenestration of Prague, Austria and the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II of Germany, embarked on a campaign against the Protestant Union and Bohemia. Zúñiga encouraged Philip to join the Austrian Habsburgs in the war, and Ambrogio Spinola, the rising star of the Spanish army, was sent at the head of the Army of Flanders to intervene. Thus, Spain entered into the Thirty Years’ War.

In 1621, the inoffensive and ineffective Philip III was replaced by the considerably more active and pious Philip IV. The following year, Zúñiga was replaced by Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, Count-Duke of Olivares, an able man who believed that the center of all Spain’s woes rest in Holland. After certain initial setbacks, the Bohemians were defeated at White Mountain in 1621, and again at Stadtlohn in 1623. The war with the Netherlands was renewed in 1621 with Spinola taking the fortress of Breda in 1625. The intervention of the Danish king Christian IV in the war worried some (Christian was one of Europe’s few monarchs who had no worries over his finances) but the victory of the Imperial general Albert of Wallenstein over the Danes at Dessau Bridge and again at Lutter, both in 1626, eliminated the threat. There was hope in Madrid that the Netherlands might finally be reincorporated into the Empire, and after the defeat of Denmark the Protestants in Germany seemed subdued. France was once again involved in her own instabilities (the famous Siege of La Rochelle began in 1627), and Spain's eminence seemed irrefutable. The Count-Duke Olivares stridently affirmed “God is Spanish and fights for our nation these days,” (Brown and Elliott, 1980, p. 190) and many of Spain’s opponents may have grudgingly agreed.

The road to Rocroi (1626–1643)

Olivares was a man sadly out of time; he realized that Spain needed to reform, and to reform it needed peace. The destruction of the United Provinces of the Netherlands was added to his list of necessities because behind every anti-Habsburg coalition there was Dutch money: Dutch bankers stood behind the East India merchants of Seville, and everywhere in the world Dutch entrepreneurship and colonists undermined Spanish and Portuguese hegemony. Spinola and the Spanish army were focused on the Netherlands, and the war seemed to be going in Spain's favor.

In 1627, the Castilian economy collapsed. The Spanish had been debasing their currency to pay for the war and prices exploded in Spain just as they had in previous years in Austria. Until 1631, parts of Castile operated on a barter economy as a result of the currency crisis, and the government was unable to collect any meaningful taxes from the peasantry, depending instead on its colonies (Spanish treasure fleet). The Spanish armies in Germany resorted to "paying themselves" on the land. Olivares, who had backed certain tax measures in Spain pending the completion of the war, was further blamed for an embarrassing and fruitless war in Italy (see War of the Mantuan Succession). The Dutch, who during the Twelve Years’ Truce had made their navy a priority, devastated Spanish and (especially) Portuguese maritime trade, on which Spain was wholly dependent after the economic collapse. The Spanish, with resources stretched thin, were increasingly unable to cope with the rapidly growing naval threats.

In 1630, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, one of the most able commanders of the time, landed in Germany and relieved the port of Stralsund that was the last stronghold on the continent held by German forces belligerent to the Emperor. Gustav then marched south winning notable victories at Breitenfeld and Lutzen, attracting greater support for the Protestant cause the further he went. The situation for the Catholics improved with Gustav's death at Lutzen in 1632 and a shocking victory for Imperial forces under Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand and Ferdinand II of Hungary at Nordlingen in 1634. From a position of strength, the Emperor approached the war-weary German states with a peace in 1635; many accepted, including the two most powerful, Brandenburg and Saxony.

Cardinal Richelieu had been a strong supporter of the Dutch and Protestants since the beginning of the war, sending funds and equipment in an attempt to stem Habsburg strength in Europe. Richelieu decided that the recently-signed Peace of Prague was contrary to French interests and declared war on the Holy Roman Emperor and Spain within months of the peace being signed. The more experienced Spanish forces scored initial successes; Olivares ordered a lightning campaign into northern France from the Spanish Netherlands, hoping to shatter the resolve of King Louis XIII's ministers and topple Richelieu before the war exhausted Spanish finances and France's military resources could be fully deployed. In the "année de Corbie", 1636, Spanish forces advanced as far south as Amiens and Corbie, threatening Paris and quite nearly ending the war on their terms.

After 1636, however, Olivares, fearful of provoking another disastrous bankruptcy, stopped the advance. The Spanish army would never again penetrate. The French thus gained time to properly mobilise. At the Battle of the Downs in 1639 a Spanish fleet was destroyed by the Dutch navy, and the Spanish found themselves unable to adequately reinforce and supply their forces in the Netherlands. The Spanish Army of Flanders, which represented the finest of Spanish soldiery and leadership, faced a French invasion led by Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé in the Spanish Netherlands at Rocroi in 1643. The Spanish, led by Francisco de Melo, were devastated, with most of the Spanish infantry slaughtered or captured by French cavalry. The high reputation of the Army of Flanders was broken at Rocroi, and with it, the grandeur of Spain.

The last Spanish Habsburgs (1643–1700)

Supported by the French, the Catalonians, Neapolitans, and Portuguese rose up in revolt against the Spanish in the 1640s. With the Spanish Netherlands effectively lost after the Battle of Lens in 1648, the Spanish made peace with the Dutch and recognized the independent United Provinces in the Peace of Westphalia that ended both the Eighty Years' War and the Thirty Years' War.

War with France continued for eleven more years. Although France suffered from a civil war from 1648–1652 (see Wars of the Fronde) the Spanish economy was so exhausted that they were unable to capitalize on French instability. Naples was retaken in 1648 and Catalonia in 1652, but the war came effectively to an end at the Battle of the Dunes where the French army under Vicomte de Turenne defeated the remnants of the Spanish army of the Netherlands. Spain agreed to the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659 that ceded to France Roussillon, Foix, Artois, and much of Lorraine.

Portugal had rebelled in 1640 under the leadership of John IV, a Braganza pretender to the throne. He had received widespread support from the Portuguese people, and the Spanish – who had to deal with rebellions elsewhere and the war with France – were unable to respond, and the Spanish and Portuguese had existed in a de facto state of peace from 1644 to 1657. When John IV died in 1657, the Spanish attempted to wrest Portugal from his son Alfonso VI, but were defeated at Ameixial (1663) and Monte Claros (1665), leading to Spain's recognition of Portuguese independence in 1668.

Philip IV, who had seen over the course of his life the devastation of Spain's empire, sank slowly into depression after he had to dismiss his favorite courtier, Olivares, in 1643. He was saddened further after the death of his son Baltasar Carlos in 1646 at the young age of seventeen. Philip became increasingly mystical near the end of his life, and ultimately attempted to undo some of the damage he had done to his country. He died in 1665 before anything could be changed, hoping his son might somehow be more fortunate. Charles, his only surviving son, was seriously deformed and mentally retarded, and remained under the influence of his mother all his life. Struggling with his deformities and the expectations and ridicule of his family and the court, Charles led a miserable existence.

Charles and his regency were incompetent in dealing with the War of Devolution that Louis XIV of France prosecuted against the Spanish Netherlands in 1667–1668, losing considerable prestige and territory, including the cities of Lille and Charleroi. In the Nine Years' War Louis once again invaded the Spanish Netherlands. French forces led by the Duke of Luxembourg defeated the Spanish at Fleurus (1690), and subsequently defeated Dutch forces under William III, who fought on Spain's side. The war ended with most of the Spanish Netherlands under French occupation, including the important cities of Ghent and Luxembourg. The war revealed to the world how vulnerable and backward the Spanish defenses and bureaucracy were, though the ineffective Spanish government took no action to improve them.

The final decades of the 17th century saw utter decay and stagnation in Spain; while the rest of Europe went through exciting changes in government and society, the Dutch Golden Age, the Glorious Revolution in England and the reign of the "Sun King" Louis XIV in France - Spain remained adrift and inward looking. The Spanish bureaucracy that had been built up around the charismatic, industrious, and intelligent Charles I and Philip II demanded a strong monarch; the weakness of Philip III and IV led it to its becoming bloated and corrupt. As his final wishes, the childless king of Spain desired that the throne pass to the Bourbon prince Philip of Anjou, rather than to a member of the family that had tormented him throughout his life. Charles II died in 1700, ending the line of Spanish Habsburgs exactly two centuries after Charles I was born.

Spanish society and the Inquisition (1516–1700)

The Spanish Inquisition was formally launched during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, continued by their Habsburg successors, and only ended in the 19th century. Under Charles I the inquisition became a formal department in the Spanish government, hurtling out of control as the 16th century progressed. Charles also passed the Limpieza, a law that excluded those not of pure Old Christian, non-Jewish blood from public office. Although torture was common in Europe, the way the Inquisition was practiced encouraged corruption and betrayal, and it became a driving factor in the decay of Spanish power. It became a method for enemies, jealous friends and even quarreling relations to usurp influence and property. An accusation, even if largely unfounded, led to a long and agonizing trial that might take years before coming to a verdict, during which time the accused's reputation and esteem was destroyed. The notorious auto de fe was a combination of public humiliation of the repentant and a gross spectacle of human torture for the "guilty".

Although no one expected the Spanish Inquisition, Philip II greatly expanded it and made church orthodoxy a goal of public policy. In 1559, three years after Philip came to power, students in Spain were forbidden to travel abroad, the leaders of the Inquisition were placed in charge of censorship, and books could no longer be imported. Philip vigorously tried to excise Protestantism out of Spain, holding innumerable campaigns to eliminate Lutheran and Calvinist literature from the country, hoping to avoid the chaos taking place in France.

The church in Spain had been purged of many of its administrative excesses in the 15th century by Cardinal Ximenes, and the Inquisition served to expurgate many of the more radical reformers who sought to change church theology as the Protestant reformers wanted. Instead, Spain became the scion of the Counter-reformation as it emerged from the Reconquista. Spain bred two unique threads of counter-reformationary thought in the persons of Saint Theresa of Avila and the Basque Ignatius Loyola. Theresa advocated strict monasticism and a revival of more ancient traditions of penitence. She experienced a mystical ecstasy that became profoundly influential on Spanish culture and art. Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuit Order, was influential across the world in his stress on spiritual and mental excellence and contributed to a resurgence of learning across Europe. In 1625, a peak of Spanish prestige and power, the Count-Duke of Olivares established the Jesuit colegia imperial in Madrid to train Spanish nobles in the humanities and military arts.

The Moriscos of southern Spain had been forcibly converted to Christianity in 1502, but under the rule of Charles I they had been able to obtain a degree of tolerance from their Christian rulers. They were allowed to practice their former custom, dress, and language, and religious laws were laxly enforced. In 1568, however, under Philip, the Moriscos rebelled (see Morisco Revolt) after the old laws were enforced again. The revolt was only put down by Italian troops under Don John of Austria, and even then the Moriscos retreated to the highlands and were not defeated until 1570. The revolt was followed by a massive resettlement program in which 12,000 Christian peasants replaced the Moriscos. In 1609, on the advice of the Duke of Lerma, Philip III expelled the 300,000 Moriscos of Spain.

The Enlightenment chiefly critiqued the Spanish for excessive religious zeal and "laziness". Among the members of the aristocracy, who enjoyed increasing security in their positions of power (unlike their colleagues in France and England who were increasingly competitive) the argument of "Spanish sloth" might apply. The expulsion of the industrious Moriscos and Jews certainly did little to help the Spanish economy and society that had relied on their work and expertise far more than the Christians realized.

The Spanish bureaucracy (1516–1700)

The Spanish received a massive influx of gold from the colonies in the New World as plunder when they were conquered, much of which Charles used to prosecute his wars in Europe. It was not until the 1540s that large deposits of silver were found in Potosí and Guanajuato and a steady source of income was obtained. The Spanish left mining to private enterprise but instituted a tax known as the "quinto real" whereby a fifth of the metal was collected by the government. The Spanish were quite successful in enforcing the tax throughout their vast empire in the New World; all bullion had to pass through the House of Trade in Seville, under the direction of the Council of the Indies. The supply of Almadén mercury, vital to extracting silver from the ore, was controlled by the state and contributed to the rigor of Spanish tax policy.

Although the initial conquests in the Americas provided sharp spikes in gold imports from the colonies, it was not until the 1550s that they became a regular and vital source of Spain's income. Inflation - both in Spain and in the rest of Europe - was primarily caused by debt; Charles had conducted most of his wars on credit, and in 1557, a year after he abdicated, Spain was forced into its first bankruptcy.

Faced with the growing threat of piracy, in 1564 the Spanish adopted a convoy system far ahead of its time, with treasure fleets leaving the Americas in April and August. The policy proved efficient, and was quite successful. Only two convoys were captured; one in 1628 when it was captured by the Dutch, and another in 1656, captured by the English, but by then the convoys were a shadow of what they had been at their peak at the end of the previous century. Nevertheless even without being completely captured they frequently came under attack, which inevitably took its toll. Not all shipping of the dispersed empire could be protected by large convoys, allowing the Dutch, English and French privateers and pirates the opportunity to devastate trade along the American and Spanish coastlines and raid isolated settlements. This became particularly savage from the 1650s, with all sides falling to extraordinary levels of barbarity, even by contemporary standards. Spain also had to deal with Barbary piracy in the Mediterranean and Oriental and Dutch piracy in the waters in and around the Philippines.

The growth of Spain's empire in the New World was accomplished from Seville, without the close direction of the leadership in Madrid. Charles I and Philip II were primarily concerned with their duties in Europe, and thus control of the Americas was handled by viceroys and colonial administrators who operated with virtual autonomy. The Habsburg kings regarded their colonies as feudal associations rather than integral parts of Spain. The Habsburgs, whose family had traditionally ruled over diverse, noncontiguous domains and had been forced to devolve autonomy to local administrators, replicated those feudal policies in Spain, particularly in the Basque country and Aragon.

This meant that taxes, infrastructure improvement, and internal trade policy were defined independently by each region, leading to many internal customs barriers and tolls, and conflicting policies even within the Habsburg domains. Charles I and Philip II had been able to master the various courts through their impressive political energy, but Philip III and IV allowed it to decay, and Charles II was wholly incapable of controlling them. The development of Spain itself was hampered by the fact that Charles I and Philip II spent most of their time abroad; for most of the 16th century, Spain was administrated from Brussels and Antwerp, and it was only during the Dutch Revolt that Philip returned to Spain, where he spent most of his time in the seclusion of the monastic palace of El Escorial. The patchy empire, held together by a determined king keeping the bloated bureaucracy together, unraveled when a weak ruler came to the throne.

There were attempts to reform the antiquated Spanish bureaucracy. Charles, on becoming king, clashed with his nobles during the Castilian War of the Communities when he attempted to fill government positions with effective Dutch and Flemish officials. Philip II encountered major resistance when he tried to enforce his authority over the Netherlands, contributing to the rebellion in that country. The Count-Duke of Olivares, Philip IV's chief minister, always regarded it as essential to Spain's survival that the bureaucracy be centralized; Olivares even backed the full union of Portugal with Spain, though he never had an opportunity to realize his ideas. Without the firm hand and diligence of Charles I and Philip II, the bureaucracy became increasingly bloated and corrupt until, by Olivares's dismissal in 1643, its poor condition rendered it obsolete.

The Spanish economy (1516–1700)

Like most of Europe, Spain had suffered from famine and plague during the 14th and 15th centuries. By 1500, Europe was beginning to emerge from these demographic disasters, and populations began to explode - Seville, which was home to 60,000 people in 1500 burgeoned to 150,000 by the end of the century. There was a substantial movement to the cities of Spain to capitalize on new opportunities as shipbuilders and merchants to service Spain's impressive and growing empire.

Inflation in Spain, as a result of state debt and the importation of silver and gold from the New World, triggered hardship for the peasantry. The average cost of goods quintupled in the 16th century in Spain, led by wool and grain. While reasonable when compared to the 20th century, prices in the 15th century changed very little, and the European economy was shaken by the so-called price revolution. Spain, along with England was Europe's only producer of wool, initially benefited from the rapid growth. However, like in England, there began in Spain an inclosure movement that stifled the growth of food and depopulated whole villages whose residents were forced to move to cities. But unlike England, the higher inflation, the burden of the Habsburg's wars and the many customs duties dividing the country and restricting trade with the Americas, stifled the growth of industry that may have provided an alternative source of income in the towns.

Sheep-farming was practiced extensively in Castile, and grew rapidly with rising wool prices with the backing of the king. Merino sheep were annually moved from the mountains of the north to the warmer south every winter, ignoring state-mandated trails that were intended to prevent the sheep from trampling the farmland. Complaints lodged against the shepherds' guild, the Mesta, were ignored by Philip II who received a great deal of revenue from wool. Eventually, Castile became barren, and Spain was wholly dependent on imported food that, given the cost of transportation and the risk of piracy, was far more expensive in Spain than elsewhere. As a result, Spain's population grew much slower than France's; by Louis XIV's time, France had a population greater than that of Spain and England combined.

Credit emerged as a widespread tool of Spanish business in the 17th century. The city of Antwerp, in the Spanish Netherlands, lay at the heart of European commerce and its bankers financed most of Charles V's and Philip II's wars on credit. The use of "notes of exchange" became common as Antwerp banks became increasingly powerful and led to extensive speculation that helped to exaggerate price shifts. Although these trends laid the foundation for the development of capitalism in Spain and Europe as a whole, the total lack of regulation and pervasive corruption meant that small landowners often lost everything with a single stroke of misfortune. Estates in Spain grew progressively larger and the economy became increasingly uncompetitive, particularly during the reigns of Philip III and IV when repeated speculative crises shook Spain.

The Roman Catholic Church had always been important to the Spanish economy, and particularly in the reigns of Philip III and IV, who had bouts of intense personal piety and church philanthropy, large areas of the country were donated to the church. The later Habsburgs did nothing to promote redistribution of land, and by the end of Charles II's reign, most of Castile was in the hands of a select few landowners, the largest of which by far was the Church.

Spanish art and culture (1516–1700)

Main article: Spanish Golden Age

The Spanish Golden Age was a flourishing period of arts and letters in Spain which spanned roughly from 1550–1650. Some of the outstanding figures of the period were El Greco, Diego Velázquez, Miguel de Cervantes, and Pedro Calderón de la Barca.

El Greco and Velázquez were both painters, the former most notably recognized for his religious depictions and the latter—now regarded as one of the most important figures in all of Spanish art—for his precise, realistic portraiture of the contemporary court of Philip IV. Cervantes and de la Barca were both writers; Don Quixote de la Mancha, by Cervantes, is one of the most famous works of the period and probably the best-known piece of Spanish literature of all time. It is a parody of the romantic, chivalric aspects of knighthood and a criticism of contemporary social structures and societal norms. Juana Inés de la Cruz, the last great writer of this golden age, died in New Spain in 1695.

This period also saw a flourishing in intellectual activity, now known as the School of Salamanca, producing thinkers that were studied throughout Europe.

See also

- Habsburg

- History of Spain

- Spanish Empire

- Global Empire

- Habsburg Monarchy

- Ottoman-Habsburg wars

- Great Plague of Seville

References

- Armstrong, Edward (1902). The emperor Charles V. New York: The Macmillan Company

- Black, Jeremy (1996). The Cambridge illustrated atlas of warfare: Renaissance to revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47033-1

- Braudel, Fernand (1972). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, trans. Siân Reynolds. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-090566-2

- Brown, J. and Elliott, J. H. (1980). A palace for a king. The Buen Retiro and the Court of Philip IV. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Brown, Jonathan (1998). Painting in Spain : 1500–1700. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06472-1

- Dominguez Ortiz, Antonio (1971). The golden age of Spain, 1516–1659. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-297-00405-0

- Edwards, John (2000). The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs, 1474–1520. New York: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-16165-1

- Harman, Alec (1969). Late Renaissance and Baroque music. New York: Schocken Books.

- Kamen, Henry (1998). Philip of Spain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07800-5

- Kamen, Henry (2003). Empire: How Spain Became a World Power, 1492–1763. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-093264-3

- Kamen, Henry (2005). Spain 1469–1714. A Society of Conflict (3rd ed.) London and New York: Pearson Longman. ISBN 0-582-78464-6

- Parker, Geoffrey (1997). The Thirty Years' War (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12883-8

- Parker, Geoffrey (1972). The Army of flanders and the Spanish road, 1567–1659; the logistics of Spanish victory and defeat in the Low Countries' Wars.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-08462-8

- Parker, Geoffrey (1977). The Dutch revolt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1136-X

- Parker, Geoffrey (1978). Philip II. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-69080-5

- Parker, Geoffrey (1997). The general crisis of the seventeenth century. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16518-0

- Stradling, R. A. (1988). Philip IV and the government of Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32333-9

- Various (1983). Historia de la literatura espanola. Barcelona: Editorial Ariel

- Wright, Esmond, ed. (1984). History of the World, Part II: The last five hundred years (3rd ed.). New York: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0-517-43644-2.

- Gallardo, Alexander (2002), "Spanish Economics in the 16th Century; Theory, Policy, and Preactice," Lincoln, NE:Writiers Club Press,2002. ISBN 0-595-26036-5.