J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover | |

|---|---|

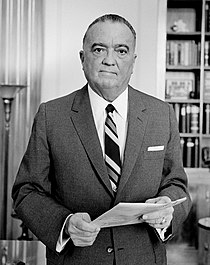

J. Edgar Hoover, photographed September 28, 1961 | |

| 1st Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation | |

| In office March 22, 1935 – May 2, 1972 | |

| Succeeded by | L. Patrick Gray |

| 6th Director of the Bureau of Investigation | |

| In office May 10, 1924 – March 22, 1935 | |

| Preceded by | William J. Burns |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 1, 1895 |

| Died | May 2, 1972 (aged 77) |

| Signature | |

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an influential but controversial Director of the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He founded the present form of the agency, and remained director for 48 years until his death in 1972, at age 77. During his life he was highly regarded by the US public, but since his death many allegations have tarnished his image.

Hoover's leadership spanned eight presidential administrations, encompassed Prohibition, the Great Depression, World War II, the Korean War, the Cold War, and the Vietnam War. During this time the United States moved from a rural nation with strong isolationist tendencies to an urbanized superpower.

Hoover has frequently been accused of exceeding and abusing his authority. He is known to have investigated individuals and groups because of their political beliefs rather than suspected criminal activity as well as using the FBI for other illegal activities such as burglaries and illegal wiretaps.[1] Hoover frequently fired FBI agents by singling out those who he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers" or he considered to be "pinheads."[2] He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations. Melvin Purvis was a prime example; he was one of the more effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs and received substantial public recognition, but a jealous Hoover maneuvered him out of the FBI.[3] It is because of Hoover's long and controversial reign that FBI directors are now limited to 10-year terms.[4]

Early life and education

Hoover was born in Washington, D.C., to Anna Marie Scheitlin and Dickerson Naylor Hoover, Sr.,[5] and grew up in the Eastern Market section of the city. Few details are known of his early years; his birth certificate was not filed until 1938. What little is known about his upbringing generally can be traced back to a single 1937 profile by journalist Jack Alexander. Hoover was educated at George Washington University, graduating in 1917 with a law degree. During his time there, he worked at the Library of Congress[6] and also became a member of Kappa Alpha Order (Alpha Nu 1914). While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock, the New York City U.S. Postal Inspector who waged prolonged campaigns against fraud and vice (as well as pornography and information on birth control) a generation earlier. He is thought to have studied Comstock's methods and modeled his early career on Comstock's reputation for relentless pursuit and occasional procedural violations in crime fighting.

Career

During World War I, Hoover found work with the Justice Department. He soon proved himself capable and was promoted to head of the Enemy Aliens Registration Section. In 1919, he became head of the new General Intelligence Division of the Justice Department (see the Palmer Raids). From there, in 1921, he joined the Bureau of Investigation as deputy head, and in 1924, the Attorney General made him the acting director. On May 10, 1924, Hoover was appointed by President Calvin Coolidge to be the sixth director of the Bureau of Investigation, following President Warren Harding's death and in response to allegations that the prior director, William J. Burns, was involved in the financial scandal(s) of the Harding administration.

When Hoover took over the Bureau of Investigation, it had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents. In the early thirties, there was an epidemic of bank robberies in the Midwest orchestrated by colorful sociopaths who took advantage of superior fire power and fast get-away cars to bedevil local law enforcement agencies. To the chagrin and increasing discomfort of authorities, such robbers were often viewed as somewhat noble in their assaults upon the banking industry, which at the time was evicting many farmers from their homesteads. That empathy reached the point that many of these desperados, particularly the dashing John Dillinger (who became famous for leaping over bank cages and his repeated escapes from jails and police traps), were de facto folk heroes whose exploits frequently captured headlines. State officials began to implore Washington to aid them in containing this lawlessness. The fact that the robbers frequently took stolen cars across state lines (a federal offense) gave Hoover and his men the green light to pursue them. Things did not go as planned, however, and there were some embarrassing foul-ups on the part of the FBI, particularly clashes with the Dillinger gang (actually led by "Handsome" Harry Pierpont). A raid on a summer lodge in Little Bohemia, Wisconsin, left an agent and a hapless civilian bystander dead, along with others wounded. All the gangsters escaped. Hoover realized that his job was now on the line and he pulled out all stops to capture the culprits. Hoover was particularly fixated on eliminating Dillinger, whose misdeeds he considered to be insults aimed directly at him and "his" bureau. In late July 1934, Melvin Purvis, the Director of Operations in the Chicago office, received a tip on the whereabouts of John Dillinger. That paid off when the gangster was cut down in a hail of gunfire outside the Biograph theater.

Because of several other highly-publicized captures or shootings of outlaws and bank robbers such as Dillinger, Alvin Karpis, and Machine Gun Kelly, the Bureau's powers were broadened and it was re-named the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1935. In 1939, the FBI became pre-eminent in the field of domestic intelligence. Hoover made changes, such as expanding and combining fingerprint files in the Identification Division to compile the largest collection of fingerprints ever. Hoover also helped to greatly expand the FBI's recruitment and create the FBI Laboratory, a division established in 1932 to examine evidence found by the FBI.

Hoover was noted for his concern about subversion, and under his leadership, the FBI spied upon tens of thousands of suspected subversives and radicals. Hoover tended to exaggerate the dangers of subversives, and many believe he overstepped his bounds in his pursuit of eliminating that perceived threat.[7]

The FBI had some successes against actual subversives and spies, however. For example, in the Quirin affair during World War II, German U-boats set two small groups of Nazi agents ashore in Florida and Long Island to cause acts of sabotage within the country. The members of these teams were apprehended due in part to the increased vigilance and intelligence gathering efforts of the FBI, but chiefly because one of the would-be saboteurs, who had spent many years as an American resident, decided to surrender himself to the authorities, leading to the apprehension of the other saboteurs still at large. President Harry Truman wrote in his memoirs: "The country had reason to be proud of and have confidence in our security agencies. They had kept us almost totally free of sabotage and espionage during the World War II".[8]

Another example of Hoover's concern over subversion is his handling of the Venona Project. The FBI inherited a pre-WWII joint project with the British to eavesdrop on Soviet spies in the UK and the United States. Hoover kept the intercepts--America's greatest counterintelligence secret--in a locked safe in his office, choosing not to inform Truman, his Attorney General McGraith or two Secretaries of State—Dean Acheson and General George Marshall—while they held office. However, he informed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the Venona Project in 1952.

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by Supreme Court decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute Communists. At this time he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO.[9] This program remained in place until it was revealed to the public in 1971, and was the cause of some of the harshest criticism of Hoover and the FBI. COINTELPRO was first used to disrupt the Communist Party, and later such organizations such as the Black Panther Party, Martin Luther King Jr.'s SCLC, the Ku Klux Klan and others. Its methods included infiltration, burglaries, illegal wiretaps, planting forged documents and spreading false rumors about key members of target organizations.[10] Some authors have charged that COINTELPRO methods also included inciting violence and arranging murders.[11]

In 1975, the activities of COINTELPRO were investigated by the Senate Church Committee and declared illegal and contrary to the Constitution.[12]

Hoover amassed significant power by collecting files containing large amounts of compromising and potentially embarrassing information on many powerful people, especially politicians. According to Laurence Silberman, appointed deputy Attorney General in early 1974, Director Clarence M. Kelley thought such files either did not exist or had been destroyed. After The Washington Post broke a story in January 1975, Kelley searched and found them in his outer office. The House Judiciary Committee then demanded that Silberman testify about them. An extensive investigation of Hoover's files by David Garrow showed that Hoover and next-in-command William Sullivan, as well as the FBI itself as an agency, was responsible. Those actions reflected the biases and prejudices of the country at large, especially in the attempts to prevent Martin Luther King, Jr., from conducting more extensive voter education drives, economic boycotts, opposing the Vietnam War, and even running for President.

In 1956, several years before he targeted King, Hoover had a public showdown with T.R.M. Howard, a civil rights leader from Mound Bayou, Mississippi. During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to thoroughly investigate the racially-motivated murders of George W. Lee, Lamar Smith, and Emmett Till. Hoover not only wrote an open letter to the press singling out these statements as "irresponsible" but secretly enlisted the help of NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall in a campaign to discredit Howard.

In the 1950s, evidence of Hoover's unwillingness to focus FBI resources on the Mafia became grist for the media and his many detractors, after famed muckraker Jack Anderson exposed the immense scope of the Mafia's organized crime network, a threat Hoover had long downplayed. Hoover's retaliation and continual harassment of Anderson lasted into the 1970s. Hoover has also been accused of trying to undermine the reputations of members of the civil rights movement. His alleged treatment of actress Jean Seberg and Martin Luther King Jr. are two such examples.

Hoover personally directed the FBI investigation into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The House Select Committee on Assassinations issued a report in 1979 critical of the performance by the FBI, the Warren Commission as well as other agencies. The report also criticized what it characterized as the FBI's reluctance to thoroughly investigate the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the president.[13]

Presidents Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson each considered firing Hoover but concluded that the political cost of doing so would be too great. [citation needed] Richard Nixon twice called in Hoover with the intent of firing him, but both times he changed his mind when meeting with Hoover. [citation needed]

Hoover maintained strong support in Congress until his death, whereupon operational command of the Bureau passed to Associate Director Clyde Tolson. Soon thereafter Nixon appointed L. Patrick Gray, a Justice Department official with no FBI experience, as Acting Director with W. Mark Felt remaining as Associate Director. As a historical note, Felt was revealed in 2005 to have been the legendary "Deep Throat" during the Watergate scandal. Some of the people whom Deep Throat's revelations helped put in prison—such as Nixon's chief counsel Chuck Colson and G. Gordon Liddy—contend that this was, at least in part, because Felt was passed over by Nixon as head of the FBI after Hoover's death in 1972.[14]

In the latter part of his career and life, Hoover was a consultant to Warner Bros. on a 1959 theatrical film about the FBI, The FBI Story, and in 1965 on Warner Brothers' long-running spin-off television series, The F.B.I.. Hoover personally made sure Warner Bros. would portray the FBI more favorably than other crime dramas of the times.

The FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C. is named after Hoover. Because of the controversial nature of Hoover's legacy, there have been periodic proposals to rename it.

Personal life

For decades, there has been speculation and rumors that Hoover was homosexual, but no concrete evidence of these claims has ever been presented. Such rumors have circulated since at least the early 1940s.[15] It has also been suggested that his long association with Clyde Tolson, an associate director of the FBI who was also Hoover's heir, was that of a gay couple. The two men were almost constantly together, working, vacationing, and having lunch and dinner together almost every weekday.[16] Some authors have dismissed the rumors about Hoover's sexuality and his relationship with Tolson in particular as unlikely,[17] while others have described them as probable or even "confirmed",[18] and still others have reported them without stating an opinion.[19]

In his 1993 biography Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J Edgar Hoover, Anthony Summers quoted a witness who claimed to have seen Hoover engaging in cross-dressing and homosexual acts on two occasions in the 1950s.[20] Summers also claimed that the Mafia had blackmail material on Hoover, and that as a consequence Hoover had been reluctant to aggressively pursue organized crime. Although never corroborated, the allegation of cross-dressing has been widely repeated, and "J. Edna Hoover" has become the subject of humor on television, in movies and elsewhere. In the words of author Thomas Doherty, "For American popular culture, the image of the zaftig FBI director as a Christine Jorgensen wanna-be was too delicious not to savor."[21] Most biographers consider the story of Mafia blackmail to be unlikely in light of the FBI's actual investigations of the Mafia.[22]

Hoover has been described as becoming increasingly a caricature of himself towards the end of his life. The book, "No Left Turns," by former agent Joseph L. Schott, portrays a rigid, paranoid old man who terrified everyone. For example, Hoover liked to write on the margins of memos. According to Schott, when one memo had too narrow margins he wrote, "watch the borders!" No one had the nerve to ask him why, but they sent inquiries to the Border Patrol about any strange activities on the Canadian and Mexican frontiers. It took a week before an HQ staffer realized the message related to the borders of the memo paper.[23]

African American author Millie McGhee claims in her 2000 book Secrets Uncovered to be related to J. Edgar Hoover.[24] McGhee's oral family history holds that a branch of her Mississippi family, also named Hoover, is related to the Washington, D.C., Hoovers, and that further, J. Edgar's father was not Dickerson Hoover as recorded, but rather Ivery Hoover of Mississippi. Genealogist George Ott investigated these claims and found some supporting circumstantial evidence, as well as unusual alterations of records pertaining to Hoover's officially recorded family in Washington, D.C., but found no conclusive proof. J. Edgar Hoover's birth certificate was not filed until 1938, when he was 43 years old.

Honors

- In 1950, King George VI of the United Kingdom awarded Hoover an honorary knighthood in the Order of the British Empire. This entitled him to the postnominal letters KBE, but not to the use of the title "Sir".

- In 1955, Hoover received the National Security Medal from President Eisenhower.[25]

- In 1966, he received the Distinguished Service Award from President Lyndon B. Johnson for his service as director of the FBI.

- The FBI headquarters in Washington, DC, is named the J. Edgar Hoover Building after him.

- On Hoover's death, Congress voted its permission for his body to lie in state in the Capitol Rotunda, an honor that, at the time, had been accorded to only twenty-one other Americans.

- Congress voted that a memorial book be published under its authority to honor Hoover's memory. "J.Edgar Hoover: Memorial Tributes in the Congress of the United States and Various Articles and Editorials Relating to His Life and Work" was published in 1974 by the Government Printing Office. The book is the official federal government compilation of addresses in Congress on the death of Hoover, and also includes an extensive selection of contemporaneous articles, editorials and obituaries.

See also

Writings

J. Edgar Hoover was the nominal author of a number of books and articles. Although it is widely believed that all of these were ghostwritten by FBI employees,[26] Hoover received the credit and royalties.

- Hoover, J. Edgar (1938). Persons In Hiding. Gaunt Publishing. ISBN 1-56169-340-5.

- Hoover, J. Edgar (1958). Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4254-8258-9.

- Hoover, J. Edgar (1962). A Study of Communism. Holt Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 0-03-031190-X.

Footnotes

- ^

Documented in Cox, John Stuart and Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) and elsewhere. - ^ Schott, Joseph L (1975). No Left Turns: The FBI in Peace & War. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-33630-1.

- ^

Purvis, Alston (2005). The Vendetta: FBI Hero Melvin Purvis's War Against Crime and J. Edgar Hoover's War Against Him. Public Affairs. pp. pp 183+. ISBN 1-58648-301-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ U.S. Code Title 28, part 2, chapter 33. sec. 533, Confirmation and Compensation of Director; Term of Service (b)

- ^ http://www.wargs.com/other/hoover.html

- ^ http://www.fbi.gov/libref/directors/hoover.htm

- ^

See, for example,

Cox, John Stuart and Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Truman291

- ^

Cox, John Stuart and Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. pp. pg. 312. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Kessler, Ronald (2002). The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. St. Martin's Paperbacks. pp. pp 107, 174, 184, 215. ISBN 0-312-98977-6.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

See for example James, Joy (2000). States of Confinement: Policing, Detention, and Prisons. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. pg. 335. ISBN 0-312-21777-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help), Williams, Kristian (2004). Our Enemies In Blue: Police And Power In America. Soft Skull Press. pp. pg. 183. ISBN 1-887128-85-9.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) and Churchill, Ward and Wall, Jim Vander (2001). Agents of Repression: The FBI's Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement. South End Press. pp. pp 53+. ISBN 0-89608-646-1.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^

"Intelligence Activities And The Rights Of Americans". 1976. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 1979. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ^ Tapes: Nixon suspected Felt. Cnn.com. June 3, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^

Terry, Jennifer (1999). An American Obsession: Science, Medicine, and Homosexuality in Modern Society. University of Chicago Press. pp. pg. 350. ISBN 0-226-79366-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Cox, John Stuart and Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. pp. pg. 108. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

For example,

Felt, W. Mark and O'Connor, John D. (2006). A G-man's Life: The FBI, Being 'Deep Throat,' And the Struggle for Honor in Washington. Public Affairs. pp. pg. 167. ISBN 1-58648-377-3.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link),

Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (2003). Cloak and Dollar: A History of American Secret Intelligence. Yale University Press. pp. pg. 93. ISBN 0-300-10159-7.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help),

Cox, John Stuart and Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. pp. pg. 108. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) "The strange likelihood is that Hoover never knew sexual desire at all." - ^

For example,

Percy, William A. and Johansson , Warren (1994). Outing: Shattering the Conspiracy of Silence. Haworth Press. pp. pp 85+. ISBN 1-56024-419-4.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link),

Summers, Anthony (1993). Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J Edgar Hoover. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-88087-X. - ^

For example,

Edited by Theoharis, Athan G. (1998). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Oryx Press. pp. pp 291, 301, 397. ISBN 0-89774-991-X.{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help),

Doherty, Thomas (2003). Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. pp 254, 255. ISBN 0-231-12952-1.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Summers, Anthony (1993). Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J Edgar Hoover. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-88087-X.

- ^

Doherty, Thomas (2003). Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. pg. 255. ISBN 0-231-12952-1.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

See for example Kessler, Ronald (2002). The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. St. Martin's Paperbacks. pp. pp 120+. ISBN 0-312-98977-6.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Schott, Joseph L (1975). No Left Turns: The FBI in Peace & War. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-33630-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ McGhee, Millie L. (2000). Secrets Uncovered: J. Edgar Hoover--Passing for White?. Inland Empire Services. ISBN 0-9701822-2-8.

- ^ "Citation and Remarks at Presentation of the National Security Medal to J. Edgar Hoover".

- ^

See, for example:

Anderson, Jack (1999). Peace, War, and Politics: An Eyewitness Account. Forge Books. pp. pg. 174. ISBN 0-312-87497-9.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help),

Powers, Richard Gid (2004). Broken: the troubled past and uncertain future of the FBI. Free Press. pp. pg. 238. ISBN 0-684-83371-9.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help),

Theoharis, Athan G. (editor) (1998). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Oryx Press. pp. pg. 264. ISBN 0-89774-991-X.{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help)

References and further reading

- Lowenthal, Max (1950). The Federal Bureau of Investigation. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0837157552.

- Schott, Joseph L (1975). No Left Turns: The FBI in Peace & War. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-33630-1.

- Garrow, David J. (1981). The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr., From 'Solo' to Memphis. W.W.Norton. ISBN 0-393-01509-2.

- Powers, Richard Gid (1986). Secrecy and Power: The Life of J. Edgar Hoover. Free Press. ISBN 0029250609.

- Gentry, Curt (1991). J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets. Plume. ISBN 0-452-26904-0.

- Theoharis, Athan (1993). From the Secret Files of J. Edgar Hoover. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-017-7.

- Beverly, William (2003). On the Lam; Narratives of Flight in J. Edgar Hoover's America. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-537-2.

- Stove, Robert J. (2003). The Unsleeping Eye: Secret Police and Their Victims. Encounter Books. ISBN 1-893554-66-X.

- Summers, Anthony (2003). Official and Confidential:The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover. Putnam Publishing Group. ISBN 0-399-13800-5.

External links

- StraightDope.com - 'The Straight Dope: Was J. Edgar Hoover a crossdresser?'

- Wall Street Journal - 'Hoover's Institution', Laurence H. Silberman, July 20, 2005

- Assassination Records Review Board - Final Report: 1998

- Yardley, Jonathan (2004). "'No Left Turns': The G-Man's Tour de Force". A review of the book "No Left Turns". Washington Post.