The Great Escape (film)

| The Great Escape | |

|---|---|

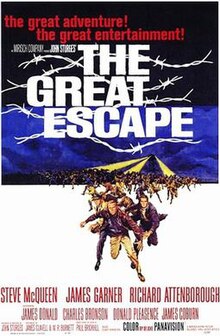

Original regular movie poster | |

| Directed by | John Sturges |

| Written by | Book: Paul Brickhill Screenplay: James Clavell W.R. Burnett |

| Produced by | John Sturges |

| Starring | Steve McQueen James Garner Richard Attenborough James Donald Charles Bronson Donald Pleasence James Coburn John Leyton David McCallum Gordon Jackson Nigel Stock Angus Lennie Lawrence Montaigne Hannes Messemer |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates | July 4, 1963 |

Running time | 172 min |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4,000,000 |

The Great Escape, written by James Clavell, W.R. Burnett, and Walter Newman (uncredited), and directed by John Sturges is a popular 1963 World War II film starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough and James Garner, based on a true story about Allied prisoners of war with a record for escaping from German prisoner-of-war camps. The Luftwaffe placed them in a new more secure camp, Stalag Luft III, from which they promptly formed a plan to break out 250 men.

The film was based upon the factual book of the same name by Paul Brickhill, who observed the actual events as a prisoner, as did George Harsh who supplied the introduction. Harsh, one of the few Americans in the British section of Stalag Luft III, died in 1980 at age 72, according to a 1980 page of obituaries in Time magazine.

Featuring an all-star cast including McQueen (whose motorcycle chase is the film's most remembered action scene; he also did many of his own stunts), James Garner, Richard Attenborough, James Coburn, Charles Bronson and Donald Pleasence, The Great Escape is regarded as a classic and frequently repeated on television.

The march tune that serves as the film's theme, written by Elmer Bernstein, has also become a classic.

Synopsis

Upset by the soldiers and resources wasted in recapturing escaped Allied prisoners of war, the German High Command concentrates the most-determined and successful of these prisoners to a new, high-security prisoner of war camp that the commandant, Colonel von Luger (Hannes Messemer), proclaims escape-proof.

The Gestapo deliver to the camp the most dangerous prisoner of all, "Big X", Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett (Richard Attenborough), warning him that he will be shot should he ever again escape. Locked up with "every escape artist in Germany", Bartlett immediately plans the greatest escape attempted — a tunnel system for exfiltrating 250 prisoners of war.

The first escape attempt, conceived whilst in the cooler, is by USAAF Capt. Virgil Hilts (McQueen) and RAF Flying Officer Archibald Ives (Angus Lennie); they are caught and returned to the cooler. Later, when the three Americans in camp (Hendley, Hilts, and Goff) are celebrating American Independence Day with the other (mainly British) PoWs, the guards discover tunnel "Tom". Because of that, the depressed Ives climbs the barbed wire fence to escape, while in view of the tower guards. Hilts notices and runs to stop him, but is too late as Ives is machine-gunned dead on the wire.

Teams of men are organised to survey, dig, hide soil, manufacture civilian clothing, forge documents, provide security and distractions, and procure contraband materials. The worst of the work noise was covered from the men choir singing, and dirt from the tunnels was concealed in the mens' trousers and emptied in the gardens. Flight Lieutenant Hendley (James Garner), "the scrounger", finds ingeniously devious ways to get whatever the others need, from a camera to identity cards. Australian Flying Officer Louis Sedgwick (James Coburn), "the manufacturer", makes many of the tools they need, such as picks for digging and bellows for pumping breathable air into the tunnels. Flight Lieutenant Danny Velinski (Charles Bronson), "the tunnel king", is in charge of digging, despite having a fear of dark enclosed spaces. Forgery is handled by Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe (Donald Pleasence), who is sent nearly blind from the highly intricate work by candlelight (progressive myopia); Hendley takes it upon himself to be Blythe's guide in the escape. Meanwhile, Captain Virgil Hilts "The Cooler King", irritates the guards with frequent escapes and irreverent behaviour. Bartlett persuades Hilts to reconnoiter the immediate vicinity of the PoW camp during one of his escapes, then allow his recapture, allowing the cartographers to create guide maps out of German territory.

The prisoners work on three escape tunnels ("Tom", "Dick", and "Harry") simultaneously. After the first tunnel is discovered by one of the Guards, Werner, Robert Graf, the prisoners abandon the second tunnel and put all their efforts into completing the third. The last part of the tunnel is completed on the night of the escape, but is found to be twenty feet short of the woods that would provide cover. Nevertheless, seventy-six men escape before one is finally spotted coming out of the tunnel.

After various attempts to reach neutral Switzerland, Sweden, and Spain, almost all of the escaped PoWs are recaptured or killed: Hendley and Blythe steal a trainer aeroplane, intending a Swiss flight; the aeroplane breaks down and crashes enroute. Soldiers arrive at the crash site, shooting Blythe while Hendley surrenders. Flight Lieutenant Cavendish (Nigel Stock), having hitched a lift in a truck, is captured at a checkpoint, discovering another fellow PoW, Haynes, captured after his German soldier disguise. Bartlett, and Mac (Gordon Jackson), are recognised at a railroad station by the Gestapo, but manage to escape after fellow PoW Eric Ashley-Pitt (David McCallum) sacrifices himself by killing the Gestapo agent; Bartlett and Mac attempt to board a bus in the town, but Mac is tricked into revealing his nationality with the same trick he had warned Haynes about before the escape. They both flee but Mac is caught shortly after, Bartlett having escaped over rooftops, but after he fools some pursuing Gestapo, he is recognised by his previous captors. Lastly, Hilts attempts to jump the barbed wire Swiss-German border fence with a stolen Wehrmacht motorcycle but his tank is hit and he becomes entangled in the wire.

Only three evade capture and make it to safety. Velinski and Flight Lieutenant Willy Dickes (the tunnel kings) steal a rowboat and proceed downriver to the Baltic coast, where they successfully board a Swedish merchant ship. Sedgewick hides in a boxcar and makes it all the way to France, and while resting in a café the local Resistance stages a drive-by shooting of some German officers. After realising he is an Allied PoW, the Resistance enlist the help of a guide to get Sedgewick into Spain.

As for the others, 48 of the re-captured PoWs, including Bartlett, Mac, Cavendish and Haynes, are shot dead in a field - this brings the total of those shot dead to 50 (including Ashley-Pitt and Blythe). Meanwhile, Hendley and Sorren and a small group of others are returned to the stalag. The Senior British Officer, Grp Cpt Ramsey (James Donald) hears of the massacre of the 50 dead from von Luger, who has been relieved of command and is swiftly driven away to face the consequences of allowing the breakout.

Hilts is brought back alone to the camp, and subsequently to the cooler. His fellow American officer Goff throws him his baseball and glove as he walks into solitary confinement. As the guard locks him in his cell and walks away, he hears the familiar sound of Hilts bouncing his baseball against the cell walls. The film ends with this scene under the caption "This picture is dedicated to the 50."

The true events

Many elements of the film are factual, but the events and characters are condensed. Hendley represents several blackmailers and suppliers; the forger, Blythe, is a composite of at least two men, Tim Walenn and James Hill. One of the organisers, Lithuanian flight captain Romualdas Marcinkus, is unmentioned in the film.

- Three tunnels were dug, shored and lighted as portrayed. The Germans discovered one just shy of completion (though it was not during some 4th of July celebrations). Sand from the tunnels was put in bags hidden in the trousers. The prisoners would wander the camp spreading the dirt. The men doing this job were known as "penguins".

- POWs who came up with plans to escape needed permission to proceed from the Escape Committee. This was in order to avoid conflicting escape plans from cancelling each other: an escaping prisoner being caught by the guards could cause the alarm to be raised and ruin another escape attempt; thus Hilts and Ives need Bartlett's permission before attempting to dig under the wire.

- Per Paul Brickhill, who didn't go through the tunnel, claimed that, due to a miscalculation, the tunnel ended short of the tree line. According to Alan Burgess, in The Longest Tunnel (1990, Grove Press), the tunnel did reach the forest, yet it was so sparse it provided insufficient cover. The escape had to proceed or the forged identity and travel papers would become invalid. The prisoners fabricated the papers and their escape suits.

- Only 76 of the projected 250 men escaped while an air raid occurred; only three POWs escaped Germany into neutral territory: the Norwegians Per Bergsland and Jens Müller who escaped to Sweden, and the Dutchman Bram van der Stok who reached Spain.

- The Gestapo killed 50 of the recaptured POWs, a serious violation of the Geneva Convention.

- Roger Bartlett was based on Roger Bushell, the mastermind of the escape, a brilliant organiser and a natural leader of men. The scar underneath the character's eye is a tribute to Bushell, a competitive skier who suffered an accident on the slopes that scarred him.

- Group Captain Nicolas Tindal was in charge of forging documents for the escapers.

- Danny Velinski is based principally on Wally Floody, a Canadian mining engineer and pilot, who was a technical advisor for the film. He was transferred elsewhere before the escape occurred. The character also represents F/Lt Ernst Valenta, F/O Danny Krol, and F/O Wlodzimierz Adam Kolanowski who designed and maintained the tunnels. They escaped, but were captured and shot.[1]

- Among the prisoners who tried to escape was Paramasiva Prabhakar Kumaramangalam who went on to become the 7th chief of the Indian army.

- One important fact kept out of the film was the help the POWs received from outside the camp, some of it from the home countries. POWs received much material from home that proved invaluable for this and other escapes. Acting through secret agencies such as MI9, families from Allied nations would send maps, papers, tools, and disguise material hidden in gifts, books, food, and other objects: for example a map of Germany could be concealed in a pen. Ex-POWs asked the filmmakers to exclude such details lest it jeopardize future POW escapes.[2].

The fictional events in the film

Elements of the film not based on fact include:

- The film depicts Tom's entrance as being under a stove and Harry's as in a drain sump in a washroom. In reality, Dick's entrance was the drain sump, Harry's was under the stove, and Tom's was in a darkened corner.

- A scene shows a choir singing to cover the noise of work done for the escape, but, in reality, it was a group of prisoners who formed a musical band and called themselves the "Sagan Serenaders". Future television meteorologist Wally Kinnan, then a First Lieutenant in the US Army Air Corps and Pilot Officer Leonard Whiteley of the British Royal Air Force had organized the group. The Serenaders received musical instruments from aid organizations and whatever the German captors could scrounge. Musicians Tiger Ward, Nick Nagorka and pianist John Bunch were also members of this group.

- No members of the American armed forces actually escaped. While many had worked on the construction of both Tom and Harry, by the time of the escape through Harry the American prisoners had all been moved to a separate compound. However, John Dodge, an American in the British Army, was one of the escapers. A BBC [1] article states the following:

- "The role of the American characters in the film is much exaggerated - indeed, they had all been moved to another compound by the time of the escape and absolutely no Americans were involved in the actual breakout. The image of the dynamic Americans helping out the rather more pedestrian British is perhaps a reflection of American perceptions of their role during the Second World War, though a more charitable interpretation is that commercial necessity dictated a more prominent role for Americans. Whatever the reason, the extensive use of creative licence to boost the role of America and Americans in films 'based' upon true stories or events is nothing new."

- Hilts's dash by motorcycle for the border is fictional. It was made on the insistence of McQueen, a keen motorcyclist, and has become one of the most famous action scenes of 1960s classic cinema. Furthermore, the motorbike used in the film is a 1960s Triumph 650 rather than an authentic but more pedestrian, BMW R 75 or Zündapp KS 750. Furthermore Hilts is shown being taken back to the POW Camp after his capture; in real life he probably would have been shot for appearing in a German uniform (however, since he flashed his air force insignia unlike the other captured soldiers, he would have been spared for still "bearing" his soldier's uniform)

- The theft of a German airplane (in the film, an Bücker Bü 181) by Hendley and Blythe is also fictitious, although there was a failed attempt by Lorne Welch and Walter Morison to steal a plane following the delousing party escape a year earlier.[3]

- Sedgwick's theft of a bicycle was something that was not recommended since an escaper could face criminal charges if recaptured.

- The murders of the 50 airmen were conducted in small numbers, not en masse. Usually as the prisoners were being driven by automobile, the men would be told to get out and stretch their legs, and would be killed by machine pistols or a gun pressed to their head. The actual murders, and the manhunt for the perpetrators after the war, is outlined in the book Exemplary Justice.

- The Kommandant of Stalag Luft III, Oberst Von Liedener, was unlike the character portrayed in the film.[4] In the film the commandant was arrested as a result of the escape; in reality his arrest was due to his dealing with black market goods.

- Blythe's blindness would have rendered him unfit for military service, or indeed contributing anything significant to the war effort, and thus would have probably been eligible for the prisoner exchange programme organised by the International Red Cross.

Cast

| Actor | Role(s) |

|---|---|

| Steve McQueen | Capt Virgil Hilts "The Cooler King" |

| James Garner | Flt Lt Anthony Hendley "The Scrounger" |

| Richard Attenborough | Sqn Ldr Roger Bartlett "Big X" |

| James Donald | Gp Capt Ramsey "The SBO" |

| Charles Bronson | Flt Lt Danny Velinski "The Tunnel King" |

| Donald Pleasence | Flt Lt Colin Blythe "The Forger" |

| James Coburn | Fg Off Louis Sedgwick "The Manufacturer" |

| Hannes Messemer | Col von Luger "The Kommandant" |

| David McCallum | Lt Cmdr Eric Ashley-Pitt "Dispersal" |

| Gordon Jackson | Flt Lt Sandy MacDonald "Intelligence" |

| Angus Lennie | Fg Off Archibald Ives "The Mole" |

| Nigel Stock | Fl Lt Denys Cavendish "The Surveyor" |

| Robert Graf | Werner 'The Ferret' |

| Jud Taylor | Goff |

Other 'great' escapes

While 76 prisoners did escape from Stalag Luft III, larger escapes occurred during World War II:

- A total of 132 Allied prisoners of war were freed by Yugoslav Partisans in a single operation in August 1944 in what is known as the raid at St Lorenzen. Almost all were successfully airlifted to Bari in Italy several weeks later.

- The Cowra breakout, August 1944, Australia: 545 Japanese POWs attempted escape and/or suicide. 231 prisoners and four Australian soldiers were killed and the surviving escapers were recaptured.

- At Sobibór extermination camp in October 1943, about 300 prisoners escaped. Only about 50 escapers survived the war. They killed at least 11 SS and Trawniki in the lead-up to the break.

- The escape from Oflag XVII-A Doellersheim, Germany. Of 131 French soldiers in September 1943 only two succeeded in evading recapture.

Sequels and remakes

Template:Infobox movie certificates A highly fictionalized, made-for-television sequel, The Great Escape II: The Untold Story, appeared many years later. It starred Christopher Reeve with Pleasence as an SS villain.

The Bollywood film Deewar: Let's Bring Our Heroes Back is based loosely on the same plot, although it involves a prisoner's (Amitabh Bachchan) son (Akshay Khanna) aiding the escape from within.

The Great Escape in popular culture

- An ad for beer was made in the early 1990s and shown on British TV. It featured some of McQueen's scenes from the film and included additional surreal footage with Griff Rhys Jones.

- Some ads for the Hummer H3 in the fall of 2006 played the tune, as the employees of a nondescript company plot a "Great escape" to drive their Hummers, with a parking lot booth attendant mimicking throwing a baseball against the wall like Steve McQueen.

- The animated film Chicken Run (2000) contains many references. The film also references Stalag 17, considered (along with "Escape") to be one of the greatest World War II prisoner-of-war movies.

- British stand-up comedian Eddie Izzard's 1997 "Dress to Kill" performance included an 8-minute segment about "The Great Escape" in which Izzard humorously questioned the plausibility of the movie's plot and the demoralizing fact that all the British characters ended tragically despite all their cunning and planning while the Americans--notably Steve McQueen--survive. Known for his surrealist, stream-of-consciousness type of stand-up comedy, Izzard would digress often during this particular routine as he tried to remember all the characters and actors. This is exemplified best on the CD version of "Dress To Kill" where Izzard gets heckled by a fan during the Great Escape bit, demanding that Izzard "moves on".

- The opening scene of Reservoir Dogs features Mr. Brown (Quentin Tarantino) explaining the premise of Madonna's "Like a Virgin" and referring to a man as being similar to Charles Bronson in The Great Escape stating, "he's digging tunnels".

- In The Parent Trap (1998), Lindsay Lohan's characters are lead to an isolated camp cabin with the Great Escape march playing over the scene.

- In a epsiode of The Simpsons where Baby Maggie tries twice to escape from a Baby sitter school-the theme music from "The Great Escape" is used.

Additional production information

- This film shares three of its stars (Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn), its director and producer (John Sturges), its composer (Elmer Bernstein), a screenwriter Walter Newman (uncredited), and its editor (Ferris Webster) with The Magnificent Seven. Both films also feature one of the stars of The Man from U.N.C.L.E.: David McCallum appears in this film while Robert Vaughn appears in the earlier one.

- Steve McQueen, an expert motorbiker, did most of his own motorbike stunts, but some of the more dangerous stunts required a double. Bud Ekins, a friend and fellow motorbike enthusiast, happened to resemble McQueen sufficiently from a distance to do the stunts without detecting the double. Ekins was only on-screen for a few seconds and his few shots were edited with the many individual shots of McQueen riding alongside and between the fences. Ekins performed the 60-foot (≈18 m) jump over the inner Austrian/Swiss border fence. He also did the scene sliding his bike into the outer fence. According to the DVD extra, McQueen did much of the bike work, even doubling as one of his own helmeted German pursuers whom Hilts hijacks to get the motorcycle. Ekins also later doubled for McQueen in Bullitt.

- As noted by David McCallum in the DVD extra, the "barbed wire" that Hilts (Steve McQueen) crashed into in the scene above was actually made of little strips of rubber tied around normal wire, and was made by the cast and crew during their free time.

- At the time of the filming, David McCallum was married to actress Jill Ireland. Years later she married fellow cast member Charles Bronson; that marriage lasted until her death after a long battle with cancer. It is believed that she met Bronson on the set of this film.

- The movie debuted at Culver Military Academy in Indiana because the commandant of the academy was an allied prisoner of war in World War II and consultant on the film.

- Donald Pleasence had served in the Royal Air Force during World War II. He was shot down and spent a year in a German prisoner-of-war camp. Screenwriter James Clavell served in the Royal Artillery and was captured by the Japanese. He was interned in Java and later the notorious Changi Prison camp in Singapore. In an archival interview in the DVD special, Pleasence said the prison camp was sufficiently realistic and that it was upsetting at first.

- Hannes Messemer was also a real-life World War II prisoner of war.

- There was a camp theatre at Stalag Luft III. Among its actors were Talbot Rothwell, Roy Dotrice, Peter Butterworth, and Rupert Davies.

- Several video games were based on the movie, including one in 1986 and one in 2003 which explained more previous escapes of the main prisoners in previous camps and followed the film's main storyline, but altered the prisoner's fates largely.

- Though the film is today a classic, it was largely ignored at the 1963 Academy Awards. Ferris Webster's editing received the only nomination, though he lost to Harold F. Kress for How the West Was Won.

- The film, like Ice Station Zebra , Lawrence Of Arabia and Reservoir Dogs, does not have a single speaking part for a woman.

Books about The Great Escape

- The Great Escape, Paul Brickhill.

- The Tunnel King, The True Story of Wally Floody & the Great Escape, Barbara Hehner. Publ.: Harper Trophy Canada 2004.

- The Longest Tunnel, Alan Burgess.

- "Tre kom tilbake" (Three returned)", the Norwegian book by surviving escapee Jens Müller. Publ.: Gyldendal 1946.

- Exemplary Justice, Allen Andrews. Details the manhunt by the Royal Air Force's special investigations unit after the war to find and bring to trial the perpetrators of the "Sagan murders".

- Project Lessons from the Great Escape (Stalag Luft III), Mark Kozak-Holland. The prisoners formally structured their work as a project. This book analyzes their efforts using modern project management methods.

- 'Wings' Day, Sydney Smith, story of Wing Commander Harry "Wings" Day Pan Books 1968 ISBN 0330024949

Notes

- ^ History in film - The Great Escape

- ^ The Great Escape: Heroes Underground documentary, available on The Great Escape DVD Special Edition.

- ^ Morison, Walter (1995). Flak and Ferrets. Sentinel Publishing. ISBN 1874767106.

- ^ Carroll, Tim (2004). The Great Escapers. Mainstream Publishers. ISBN 1-84018-904-5.

External links

- The Great Escape at IMDb

- The Real Great Escape

- Great Escape (PBS Nova)

- Detailed information about the real event

- Exhibition about this and other escapes at the Imperial War Museum, London (until 31 July 2006)

- First hand account of Stalag Luft III by Wing Commander Ken Rees

- Pivotal Games site for the computer game version of The Great Escape

- World of Spectrum entry for the 1986 video game

- Project Management lessons from the Great Escape

- Interactive map of Tunnel Harry

- James Garner Interview on the Charlie Rose Show

- James Garner interview at Archive of American Television