The Seventh Seal

- For the Biblical concept, see Seven seals. For the Rakim album, see The Seventh Seal (Rakim album).

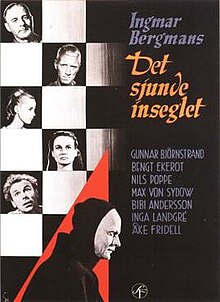

| Det sjunde inseglet | |

|---|---|

Original Swedish poster | |

| Directed by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Written by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Produced by | Allan Ekelund |

| Starring | Max von Sydow Gunnar Björnstrand Bengt Ekerot Nils Poppe |

| Cinematography | Gunnar Fischer |

| Edited by | Lennart Wallén |

| Distributed by | Svensk Filmindustri Palador Pictures Pvt. Ltd. (India) |

Release dates | |

Running time | 96 min. |

| Language | Swedish |

| Budget | $150,000 (estimated) |

The Seventh Seal (Swedish: Det sjunde inseglet) is an existential 1957 Swedish film directed by Ingmar Bergman about the journey of a medieval knight (Max von Sydow) across a plague-ridden landscape, and a monumental game of chess between himself and the personification of Death, who has come to take his life. The film has long been regarded a masterpiece of cinema. [1]

The title refers to a passage about the end of the world from the Book of Revelation, used both at the very start of the film, and again towards the end, beginning with the words "And when he had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour" (Revelation 8:1). Bergman developed the film from his own play Wood Painting.

Synopsis

Antonius Block (Max von Sydow), a knight, returns with his squire Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand) from the Crusades and finds that his home country is ravaged by the plague. To his dismay, he discovers that Death (Bengt Ekerot) has come for him too. In order to reach his home and be reunited with his wife after ten years of war, he challenges Death to a chess match.

The knight's faith is war-weathered, and this theme is stressed in one of the scenes in the movie: the knight gives confession to a priest about his doubts whether God actually exists; he tells the priest how he challenged Death to a game of chess and reveals his strategy, only to find that the priest is actually Death. In another powerful scene—of a witch-burning—the knight asks the witch to summon Satan in order to ask him whether or not God exists. When the witch summons Satan, the knight (or the audience) can't see him and the knight's dilemma is left unanswered. The witch says, "the priests see him, the soldiers see him, but the knight still cannot see him." The dialogue seems to hint that Satan is personified as priests and soldiers. When the witch is burned, the squire says that the witch doesn't see God or Satan because neither exists and that the witch's eyes are only filled with emptiness. The disquieted knight refuses to acknowledge the victim's emptiness (and, in a way, his own) despite his doubts about God. The knight realizes that he would rather be broken in faith, constantly suffering doubt, than recognize a life without meaning.

Gerald Mast writes,

“Like the gravedigger in “Hamlet”, the Squire [...] treats death as a bitter and hopeless joke. Since we all play chess with death, and since we all must suffer through that hopeless joke, the only question about the game is how long it will last and how well we will play it. To play it well, to live, is to love and not to hate the body and the mortal as the Church urges in Bergman's metaphor.”[2]

During the fateful journey, Block and the squire encounter several features of medieval society and the way it dealt with the fear of death: the penitence of flagellants, the burning of a witch, and traveling actors. Bergman is particularly critical in his depiction of the clergymen, who profit from the atmosphere of terror engendered by the plague. They offer no spiritual comfort to their people, and are represented as little better than thieves. The witch is burnt at the stake for "having caused" the plague, in the community's “grotesque effort to put an end to the contagion” (Livingston 1982: 61). The witch-burning and the painful ritual that Jof is subjected to at the inn can be viewed as archaic rituals which aim at the purification of the community through sacrifice; violence is used to stabilize the order.[3]

Bergman contrasts the despairing unbelief of the knight and the bitterness of his squire with the simple spiritual faith of the acrobat player Jof (Nils Poppe) and his young wife Mia (Bibi Andersson), who, together with their infant son Mikael, may be symbolic of the Holy family. The squire (Gunnar Björnstrand), while forcefully atheistic and cynical, displays a sensitivity that drives him to protect and aid those he can, and to sympathize with those (like the witch) he cannot.

Although the knight tells a "priest" (Death in disguise) that he is going to defeat Death by "a combination of the knight and the bishop", he will eventually still lose. But the knight achieves one significant act that gives his life meaning: he allows the young couple and their child to escape. Ironically, while the young couple are seen fleeing in the background, Block tells death "Nothing escapes you." Death bears a wide a grin and replies "Nothing escapes me. No one escapes me." While the knight and his followers are led away over the hills in a medieval dance of death, seen by Jof as a vision, the young family live on and walk into the sunrise.

Historical accuracy

The medieval Sweden portrayed in this movie is not totally accurate. It is extremely unlikely that a knight returning from the Crusades would arrive home in the middle of the Black Death, for the last crusade (the Ninth) ended in 1271, and the bubonic plague hit Europe in 1348. In addition, the flagellant movement was foreign to Sweden, large-scale witch persecutions only began in the 1400s, and the theme of life and death as portrayed in the movie is more typical of existentialism in the 1950s than of the beliefs of medieval Swedes.[4] At one point in the film Death captures the Queen in the chess game between Antonius and himself, and this is portrayed as a major setback. However, the Queen was not as powerful (as it currently is) until centuries later, when a chess-variant initially called "chess of the mad queen" became more popular than the traditional game.

Despite these historical inaccuracies, some of the film's images are derived from medieval art. For example, Bergman has stated that the image of a man playing chess with a skeletal Death was inspired by a medieval church painting from the 1480s in Täby kyrka, Täby, north of Stockholm, painted by Albertus Pictor.[5]

Production

In interviews and in his autobiography, The Magic Lantern, Bergman has said that The Seventh Seal was a low-budget affair [citation needed] . Bergman had been given the go-ahead for the project from Carl-Anders Dymling at Svensk Filmindustri only after the success at Cannes of Smiles of a Summer Night, and was given a schedule of only thirty-five days, a short time for a film of this nature [citation needed] .

The famous opening scenes with Death and the Knight were shot at Hovs Hallar, a rocky, precipitous beach area in north-western Scania [citation needed] .

Impact

The Seventh Seal was Bergman's breakthrough film. When the film won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1957, the attention generated by it (along with the previous year's Smiles of a Summer Night) made Bergman and his stars Max von Sydow and Bibi Andersson well-known to the European film community, and the critics and readers of Cahiers du Cinéma, among others, discovered him with this movie. Within five years of this, he had established himself as the first real auteur of Swedish cinema.

With its reflections upon death and the meaning of life, The Seventh Seal became something of a figurehead for "serious" European films and, as such, has often been parodied in film and television. The representation of Death as a white-faced man in a dark cape has been the most popular object of parody, most notably in Woody Allen's Love and Death, and in the film Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey, in which the protagonists beat Death at Battleship, Clue, electric football and Twister. In the movie Last Action Hero, the film character of Death (played by Ian McKellen) walks out of a movie screening of The Seventh Seal into the real world.

The character of Anton Chigurh in the film No Country for Old Men has been compared to Bergman's character of Death, with their shared indestructibility, games of chance with their intended victims, and even similar dialogue. [6]

Cast

- Gunnar Björnstrand - Jöns, squire

- Bengt Ekerot - Death

- Nils Poppe - Jof

- Max von Sydow - Antonius Block, knight

- Bibi Andersson - Mia, Jof's wife

- Inga Gill - Lisa, blacksmith's wife

- Maud Hansson - Witch

- Inga Landgré - Karin, Block's wife

- Gunnel Lindblom - Girl

- Bertil Anderberg - Raval

- Anders Ek - The Monk

- Åke Fridell - Blacksmith Plog

- Gunnar Olsson - Albertus Pictor, church painter

- Erik Strandmark - Jonas Skat

See also

References

- ^

Ebert, Roger (2000-04-16). "Great Movies - The Seventh Seal". Retrieved 2007-08-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Gerald Mast A Short History of the Movies. p.405

- ^ Mast, Short History, 62.

- ^ Said by Swedish historian Dick Harrison in an introduction to the movie on Sveriges Television, 2005. Reiterated in his book Gud vill det! ISBN 91-7037-119-9

- ^ Stated in Marie Nyreröd's interview series (the first part named Bergman och filmen) aired on Sveriges Television Easter 2004.

- ^ DuBos, David. "MovieTalk with David DuBos". New Orleans Magazine. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Bibliography

- Ingmar Bergman and the Rituals of Art by Paisley Livingston. Cornell University Press, 1982.