RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a nucleic acid that consists of a long chain of nucleotide units. Each nucleotide consists of a nitrogenous base, a ribose sugar, and a phosphate. RNA is very similar to DNA, but differs in a few important structural details: in the cell, RNA is usually single-stranded, while DNA is usually double-stranded; RNA nucleotides contain ribose while DNA contains deoxyribose (a type of ribose that lacks one oxygen atom); and RNA has the base uracil rather than thymine that is present in DNA. the day i was born was a very gd day because i was born and if i wasnt born then u ouldnt see me writing tht.Bold textRNA is transcribed from DNA by enzymes called RNA polymerases and is generally further processed by other enzymes. RNA is central to the synthesis of proteins. Here, a type of RNA called messenger RNA carries information from DNA to structures called ribosomes. These ribosomes are made from proteins and ribosomal RNAs, which come together to form a molecular machine that can read messenger RNAs and translate the information they carry into proteins. There are RNAs with other roles – in particular regulating which genes are expressed, but also as the genome of most viruses.

Structure

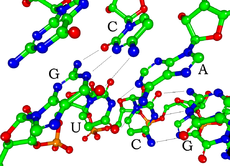

Each nucleotide in RNA contains a ribose sugar, with carbons numbered 1' through 5'. A base is attached to the 1' position, generally adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) or uracil (U). Adenine and guanine are purines, cytosine and uracil are pyrimidines. A phosphate group is attached to the 3' position of one ribose and the 5' position of the next. The phosphate groups have a negative charge each at physiological pH, making RNA a charged molecule (polyanion). The bases may form hydrogen bonds between cytosine and guanine, between adenine and uracil and between guanine and uracil.[1] However other interactions are possible, such as a group of adenine bases binding to each other in a bulge,[2] or the GNRA tetraloop that has a guanine–adenine base-pair.[1]

An important structural feature of RNA that distinguishes it from DNA is the presence of a hydroxyl group at the 2' position of the ribose sugar. The presence of this functional group causes the helix to adopt the A-form geometry rather than the B-form most commonly observed in DNA.[3] This results in a very deep and narrow major groove and a shallow and wide minor groove.[4] A second consequence of the presence of the 2'-hydroxyl group is that in conformationally flexible regions of an RNA molecule (that is, not involved in formation of a double helix), it can chemically attack the adjacent phosphodiester bond to cleave the backbone.[5]

RNA is transcribed with only four bases (adenine, cytosine, guanine and uracil),[6] but there are numerous modified bases and sugars in mature RNAs. Pseudouridine (Ψ), in which the linkage between uracil and ribose is changed from a C–N bond to a C–C bond, and ribothymidine (T), are found in various places (most notably in the TΨC loop of tRNA).[7] Another notable modified base is hypoxanthine, a deaminated adenine base whose nucleoside is called inosine. Inosine plays a key role in the wobble hypothesis of the genetic code.[8] There are nearly 100 other naturally occurring modified nucleosides,[9] of which pseudouridine and nucleosides with 2'-O-methylribose are the most common.[10] The specific roles of many of these modifications in RNA are not fully understood. However, it is notable that in ribosomal RNA, many of the post-transcriptional modifications occur in highly functional regions, such as the peptidyl transferase center and the subunit interface, implying that they are important for normal function.[11]

The functional form of single stranded RNA molecules, just like proteins, frequently requires a specific tertiary structure. The scaffold for this structure is provided by secondary structural elements which are hydrogen bonds within the molecule. This leads to several recognizable "domains" of secondary structure like hairpin loops, bulges and internal loops.[12] Since RNA is charged, metal ions such as Mg2+ are needed to stabilise many secondary structures.[13]

Comparison with DNA

RNA and DNA differ in three main ways. First, unlike DNA which is double-stranded, RNA is a single-stranded molecule in most of its biological roles and has a much shorter chain of nucleotides. Second, while DNA contains deoxyribose, RNA contains ribose, (there is no hydroxyl group attached to the pentose ring in the 2' position in DNA). These hydroxyl groups make RNA less stable than DNA because it is more prone to hydrolysis. Third, the complementary base to adenine is not thymine, as it is in DNA, but rather uracil, which is an unmethylated form of thymine.[14]

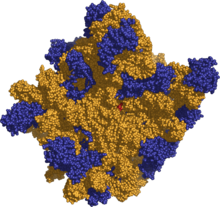

Like DNA, most biologically active RNAs including tRNA, rRNA, snRNAs and other, non-coding RNAs are extensively base paired to form double helices. Structural analysis of these RNAs have revealed that they are highly structured. Unlike DNA, this structure is not long double helices but rather collections of short helices packed together into structures akin to proteins. In this fashion, RNAs can achieve chemical catalysis, like enzymes.[15] For instance, determination of the structure of the ribosome—an enzyme that catalyzes peptide bond formation—revealed that its active site is composed entirely of RNA.[16]

Synthesis

Synthesis of RNA is usually catalyzed by an enzyme—RNA polymerase—using DNA as a template, a process known as transcription. Initiation of transcription begins with the binding of the enzyme to a promoter sequence in the DNA (usually found "upstream" of a gene). The DNA double helix is unwound by the helicase activity of the enzyme. The enzyme then progresses along the template strand in the 3’ to 5’ direction, synthesizing a complementary RNA molecule with elongation occurring in the 5’ to 3’ direction. The DNA sequence also dictates where termination of RNA synthesis will occur.[17]

RNAs are often modified by enzymes after transcription. For example, a poly(A) tail and a 5' cap are added to eukaryotic pre-mRNA.

There are also a number of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases that use RNA as their template for synthesis of a new strand of RNA. For instance, a number of RNA viruses (such as poliovirus) use this type of enzyme to replicate their genetic material.[18] Also, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is part of the RNA interference pathway in many organisms.[19]

Types of RNA

Overview

Messenger RNA (mRNA) is the RNA that carries information from DNA to the ribosome, the sites of protein synthesis (translation) in the cell. The coding sequence of the mRNA determines the amino acid sequence in the protein that is produced.[20] Many RNAs do not code for protein however. These non-coding RNAs can be encoded by their own genes (RNA genes), but can also derive from mRNA introns.[21] The most prominent examples of non-coding RNAs are transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), both of which are involved in the process of translation.[14] There are also non-coding RNAs involved in gene regulation, RNA processing and other roles. Certain RNAs are able to catalyse chemical reactions such as cutting and ligating other RNA molecules,[22] and the catalysis of peptide bond formation in the ribosome;[16] these are known as ribozymes.

In translation

Messenger RNA (mRNA) carries information about a protein sequence to the ribosomes, the protein synthesis factories in the cell. It is coded so that every three nucleotides (a codon) correspond to one amino acid. In eukaryotic cells, once precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA) has been transcribed from DNA, it is processed to mature mRNA. This removes its introns—non-coding sections of the pre-mRNA. The mRNA is then exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it is bound to ribosomes and translated into its corresponding protein form with the help of tRNA. In prokaryotic cells, which do not have nucleus and cytoplasm compartments, mRNA can bind to ribosomes while it is being transcribed from DNA. After a certain amount of time the message degrades into its component nucleotides with the assistance of ribonucleases.[20]

Transfer RNA (tRNA) is a small RNA chain of about 80 nucleotides that transfers a specific amino acid to a growing polypeptide chain at the ribosomal site of protein synthesis during translation. It has sites for amino acid attachment and an anticodon region for codon recognition that binds to a specific sequence on the messenger RNA chain through hydrogen bonding.[21]

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is the catalytic component of the ribosomes. Eukaryotic ribosomes contain four different rRNA molecules: 18S, 5.8S, 28S and 5S rRNA. Three of the rRNA molecules are synthesized in the nucleolus, and one is synthesized elsewhere. In the cytoplasm, ribosomal RNA and protein combine to form a nucleoprotein called a ribosome. The ribosome binds mRNA and carries out protein synthesis. Several ribosomes may be attached to a single mRNA at any time.[20] rRNA is extremely abundant and makes up 80% of the 10 mg/ml RNA found in a typical eukaryotic cytoplasm.[23]

Transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) is found in many bacteria and plastids. It tags proteins encoded by mRNAs that lack stop codons for degradation and prevents the ribosome from stalling.[24]

Regulatory RNAs

Several types of RNA can downregulate gene expression by being complementary to a part of an mRNA or a gene's DNA. MicroRNAs (miRNA; 21-22 nt) are found in eukaryotes and act through RNA interference (RNAi), where an effector complex of miRNA and enzymes can break down mRNA which the miRNA is complementary to, block the mRNA from being translated, or accelerate its degradation.[25][26] While small interfering RNAs (siRNA; 20-25 nt) are often produced by breakdown of viral RNA, there are also endogenous sources of siRNAs.[27] siRNAs act through RNA interference in a fashion similar to miRNAs. Some miRNAs and siRNAs can cause genes they target to be methylated, thereby decreasing or increasing transcription of those genes.[28][29][30] Animals have Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNA; 29-30 nt) which are active in germline cells and are thought to be a defense against transposons and play a role in gametogenesis.[31][32] Antisense RNAs are widespread among bacteria; most downregulate a gene, but a few are activators of transcription.[33] One way antisense RNA can act is by binding to an mRNA, forming double-stranded RNA that is enzymatically degraded.[34] There are many mRNA-like long noncoding RNAs that regulate genes in eukaryotes,[35] one such RNA is Xist which coats one X chromosome in female mammals and inactivates it.[36]

An mRNA may contain regulatory elements itself, such as riboswitches, in the 5' UTR or 3' UTR; these cis-regulatory elements regulate the activity of that mRNA.[37]

In RNA processing

Many RNAs are involved in modifying other RNAs. Introns are spliced out of pre-mRNA by spliceosomes, which contain several small nuclear RNAs (snRNA),[14] or the introns can be ribozymes that are spliced by themselves.[38] RNA can also be altered by having its nucleotides modified to other nucleotides than A, C, G and U. In eukaryotes, modifications of RNA nucleotides are generally directed by small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNA; 60-300 nt),[21] found in the nucleolus and cajal bodies. snoRNAs associate with enzymes and guide them to a spot on an RNA by basepairing to that RNA. These enzymes then perform the nucleotide modification. rRNAs and tRNAs are extensively modified, but snRNAs and mRNAs can also be the target of base modification.[39][40]

RNA genomes

Like DNA, RNA can carry genetic information. RNA viruses have genomes composed of RNA, plus a variety of proteins encoded by that genome. The viral genome is replicated by some of those proteins, while other proteins protect the genome as the virus particle moves to a new host cell. Viroids are another group of pathogens, but they consist only of RNA, do not encode any protein and are replicated by a host plant cell's polymerase.[41]

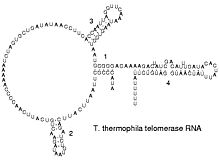

In reverse transcription

Reverse transcribing viruses replicate their genomes by reverse transcribing DNA copies from their RNA; these DNA copies are then transcribed to new RNA. Retrotransposons also spread by copying DNA and RNA from one another,[42] and telomerase contains an RNA that is used as template for building the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes.[43]

Double-stranded RNA

Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is RNA with two complementary strands, similar to the DNA found in all cells. dsRNA forms the genetic material of some viruses (double-stranded RNA viruses). Double-stranded RNA such as viral RNA or siRNA can trigger RNA interference in eukaryotes, as well as interferon response in vertebrates.[44][45][46]

Discovery

Nucleic acids were discovered in 1868 by Friedrich Miescher, who called the material 'nuclein' since it was found in the nucleus.[47] It was later discovered that prokaryotic cells, which do not have a nucleus, also contain nucleic acids. The role of RNA in protein synthesis was suspected already in 1939.[48] Severo Ochoa won the 1959 Nobel Prize in Medicine after he discovered how RNA is synthesized.[49] The sequence of the 77 nucleotides of a yeast tRNA was found by Robert W. Holley in 1965,[50] winning Holley the 1968 Nobel Prize in Medicine. In 1967, Carl Woese realized RNA can be catalytic and proposed that the earliest forms of life relied on RNA both to carry genetic information and to catalyze biochemical reactions—an RNA world.[51][52] In 1976, Walter Fiers and his team determined the first complete nucleotide sequence of an RNA virus genome, that of bacteriophage MS2.[53] In 1990 it was found in petunia that introduced genes can silence similar genes of the plant's own, now known to be a result of RNA interference.[54][55] At about the same time, 22 nt long RNAs, now called microRNAs, were found to have a role in the development of C. elegans.[56] The discovery of gene regulatory RNAs has led to attempts to develop drugs made of RNA, such as siRNA, to silence genes.[57]

See also

- Genetics

- Molecular biology

- Phosphoramidite

- Quantification of nucleic acids

- RNA Ontology Consortium

- Sequence profiling tool

- RNA extraction

- RNA structure prediction

References

- ^ a b Lee JC, Gutell RR (2004). "Diversity of base-pair conformations and their occurrence in rRNA structure and RNA structural motifs". J. Mol. Biol. 344 (5): 1225–49. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.072. PMID 15561141.

- ^ Barciszewski J, Frederic B, Clark C (1999). RNA biochemistry and biotechnology. Springer. pp. 73–87. ISBN 0792358627. OCLC 52403776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Salazar M, Fedoroff OY, Miller JM, Ribeiro NS, Reid BR (1992). "The DNA strand in DNAoRNA hybrid duplexes is neither B-form nor A-form in solution". Biochemistry. 32 (16): 4207–15. doi:10.1021/bi00067a007. PMID 7682844.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hermann T, Patel DJ (2000). "RNA bulges as architectural and recognition motifs". Structure. 8 (3): R47. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00110-6. PMID 10745015.

- ^ Mikkola S, Nurmi K, Yousefi-Salakdeh E, Strömberg R, Lönnberg H (1999). "The mechanism of the metal ion promoted cleavage of RNA phosphodiester bonds involves a general acid catalysis by the metal aquo ion on the departure of the leaving group". Perkin transactions 2: 1619–26. doi:10.1039/a903691a.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jankowski JAZ, Polak JM (1996). Clinical gene analysis and manipulation: Tools, techniques and troubleshooting. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0521478960. OCLC 33838261.

- ^ Yu Q, Morrow CD (2001). "Identification of critical elements in the tRNA acceptor stem and TΨC loop necessary for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity". J Virol. 75 (10): 4902–6. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.10.4902-4906.2001. PMID 11312362.

- ^ Elliott MS, Trewyn RW (1983). "Inosine biosynthesis in transfer RNA by an enzymatic insertion of hypoxanthine". J. Biol. Chem. 259 (4): 2407–10. PMID 6365911.

- ^ Söll D, RajBhandary U (1995). TRNA: Structure, biosynthesis, and function. ASM Press. p. 165. ISBN 155581073X. OCLC 183036381 30663724.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ Kiss T (2001). "Small nucleolar RNA-guided post-transcriptional modification of cellular RNAs". The EMBO Journal. 20: 3617–22. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.14.3617. PMID 11447102.

- ^ King TH, Liu B, McCully RR, Fournier MJ (2002). "Ribosome structure and activity are altered in cells lacking snoRNPs that form pseudouridines in the peptidyl transferase center". Molecular Cell. 11 (2): 425–35. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00040-6. PMID 12620230.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mathews DH, Disney MD, Childs JL, Schroeder SJ, Zuker M, Turner DH (2004). "Incorporating chemical modification constraints into a dynamic programming algorithm for prediction of RNA secondary structure". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101 (19): 7287–92. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401799101. PMID 15123812.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tan ZJ, Chen SJ (2008). "Salt dependence of nucleic acid hairpin stability". Biophys. J. 95: 738–52. doi:10.1529/biophysj.108.131524. PMID 18424500.

- ^ a b c Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L (2002). Biochemistry (5th edition ed.). WH Freeman and Company. pp. 118–19, 781–808. ISBN 0-7167-4684-0. OCLC 179705944 48055706 59502128.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check|oclc=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Higgs PG (2000). "RNA secondary structure: physical and computational aspects". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 33: 199–253. doi:10.1017/S0033583500003620. PMID 11191843.

- ^ a b Nissen P, Hansen J, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA (2000). "The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis". Science. 289 (5481): 920–30. doi:10.1126/science.289.5481.920. PMID 10937990.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nudler E, Gottesman ME (2002). "Transcription termination and anti-termination in E. coli". Genes to Cells. 7: 755–68. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00563.x. PMID 12167155.

- ^ Jeffrey L Hansen, Alexander M Long, Steve C Schultz (1997). "Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of poliovirus". Structure. 5 (8): 1109–22. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(97)00261-X. PMID 9309225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ahlquist P (2002). "RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases, Viruses, and RNA Silencing". Science. 296 (5571): 1270–73. doi:10.1126/science.1069132. PMID 12016304.

- ^ a b c Cooper GC, Hausman RE (2004). The Cell: A Molecular Approach (3rd edition ed.). Sinauer. pp. 261–76, 297, 339–44. ISBN 0-87893-214-3. OCLC 174924833 52121379 52359301 56050609.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ a b c Wirta W (2006). Mining the transcriptome – methods and applications (PDF). Stockholm: School of Biotechnology, Royal Institute of Technology. ISBN 91-7178-436-5. OCLC 185406288.

- ^ Rossi JJ (2004). "Ribozyme diagnostics comes of age". Chemistry & Biology. 11 (7): 894–95. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.002.

- ^ Kampers T, Friedhoff P, Biernat J, Mandelkow E-M, Mandelkow E (1996). "RNA stimulates aggregation of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments". FEBS Letters. 399: 104D. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01386-5. PMID 8985176.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gueneau de Novoa P, Williams KP (2004). "The tmRNA website: reductive evolution of tmRNA in plastids and other endosymbionts". Nucleic Acids Res. 32 (Database issue): D104–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh102. PMID 14681369.

- ^ Wu L, Belasco JG (2008). "Let me count the ways: mechanisms of gene regulation by miRNAs and siRNAs". Mol. Cell. 29 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.010. PMID 18206964.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Matzke MA, Matzke AJM (2004). "Planting the seeds of a new paradigm". PLoS Biology. 2 (5): e133. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020133. PMID 15138502.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Vazquez F, Vaucheret H, Rajagopalan R, Lepers C, Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Hilbert J, Bartel DP, Crété P (2004). "Endogenous trans-acting siRNAs regulate the accumulation of Arabidopsis mRNAs". Molecular Cell. 16 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.028. PMID 15469823.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW (2005). "Silence from within: endogenous siRNAs and miRNAs". Cell. 122 (1): 9–12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.030. PMID 16009127.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Doran G (2007). "RNAi – Is one suffix sufficient?". Journal of RNAi and Gene Silencing. 3 (1): 217–19.

- ^ Pushparaj PN, Aarthi JJ, Kumar SD, Manikandan J (2008). "RNAi and RNAa - The Yin and Yang of RNAome". Bioinformation. 2 (6): 235–7. PMC 2258431. PMID 18317570.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Horwich MD, Li C Matranga C, Vagin V, Farley G, Wang P, Zamore PD (2007). "The Drosophila RNA methyltransferase, DmHen1, modifies germline piRNAs and single-stranded siRNAs in RISC". Current Biology. 17: 1265–72. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.030. PMID 17604629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA (2006). "A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins". Nature. 442: 199–202. doi:10.1038/nature04917. PMID 16751776.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wagner EG, Altuvia S, Romby P (2002). "Antisense RNAs in bacteria and their genetic elements". Adv Genet. 46: 361–98. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(02)46013-0. PMID 11931231.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gilbert SF (2003). Developmental Biology (7th ed ed.). Sinauer. pp. 101–3. ISBN 0878932585. OCLC 154656422 154663147 174530692 177000492 177316159 51544170 54743254 59197768 61404850 66754122.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ Amaral PP, Mattick JS (2008). "Noncoding RNA in development". Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. doi:10.1007/s00335-008-9136-7. PMID 18839252.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Heard E, Mongelard F, Arnaud D, Chureau C, Vourc'h C, Avner P (1999). "Human XIST yeast artificial chromosome transgenes show partial X inactivation center function in mouse embryonic stem cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96 (12): 6841–46. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.12.6841. PMID 10359800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Batey RT (2006). "Structures of regulatory elements in mRNAs". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16 (3): 299–306. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.001. PMID 16707260.

- ^ Steitz TA, Steitz JA (1993). "A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (14): 6498–502. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. PMID 8341661.

- ^ Xie J, Zhang M, Zhou T, Hua X, Tang L, Wu W (2007). "Sno/scaRNAbase: a curated database for small nucleolar RNAs and cajal body-specific RNAs". Nucleic Acids Res. 35: D183–7. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl873. PMID 17099227.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Omer AD, Ziesche S, Decatur WA, Fournier MJ, Dennis PP (2003). "RNA-modifying machines in archaea". Molecular Microbiology. 48 (3): 617–29. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03483.x. PMID 12694609.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Daròs JA, Elena SF, Flores R (2006). "Viroids: an Ariadne's thread into the RNA labyrinth". EMBO Rep. 7 (6): 593–8. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400706. PMID 16741503.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kalendar R, Vicient CM, Peleg O, Anamthawat-Jonsson K, Bolshoy A, Schulman AH (2004). "Large retrotransposon derivatives: abundant, conserved but nonautonomous retroelements of barley and related genomes". Genetics. 166 (3): D339. doi:10.1534/genetics.166.3.1437. PMID 15082561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Podlevsky JD, Bley CJ, Omana RV, Qi X, Chen JJ (2008). "The telomerase database". Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (Database issue): D339–43. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm700. PMID 18073191.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blevins T; et al. (2006). "Four plant Dicers mediate viral small RNA biogenesis and DNA virus induced silencing". Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (21): 6233–46. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl886. PMID 17090584.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Jana S, Chakraborty C, Nandi S, Deb JK (2004). "RNA interference: potential therapeutic targets". Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 65 (6): 649–57. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1732-1. PMID 15372214.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schultz U, Kaspers B, Staeheli P (2004). "The interferon system of non-mammalian vertebrates". Dev. Comp. Immunol. 28 (5): 499–508. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.009. PMID 15062646.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dahm R (2005). "Friedrich Miescher and the discovery of DNA". Developmental Biology. 278 (2): 274–88. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.028. PMID 15680349.

- ^ Caspersson T, Schultz J (1939). "Pentose nucleotides in the cytoplasm of growing tissues". Nature. 143: 602–3. doi:10.1038/143602c0.

- ^ Ochoa S (1959). "Enzymatic synthesis of ribonucleic acid" (PDF). Nobel Lecture.

- ^ Holley RW; et al. (1965). "Structure of a ribonucleic acid". Science. 147 (1664): 1462–65. doi:10.1126/science.147.3664.1462. PMID 14263761.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Siebert S (2006). "Common sequence structure properties and stable regions in RNA secondary structures" (PDF). Dissertation, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität, Freiburg im Breisgau. p. 1.

- ^ Szathmáry E (1999). "The origin of the genetic code: amino acids as cofactors in an RNA world". Trends Genet. 15 (6): 223–9. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01730-8. PMID 10354582.

- ^ Fiers W; et al. (1976). "Complete nucleotide-sequence of bacteriophage MS2-RNA: primary and secondary structure of replicase gene". Nature. 260: 500–7. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R (1990). "Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans". Plant Cell. 2 (4): 279–89. doi:10.1105/tpc.2.4.279. PMID 12354959.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dafny-Yelin M, Chung SM, Frankman EL, Tzfira T (2007). "pSAT RNA interference vectors: a modular series for multiple gene down-regulation in plants". Plant Physiol. 145 (4): 1272–81. doi:10.1104/pp.107.106062. PMC 2151715. PMID 17766396.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ruvkun G (2001). "Glimpses of a tiny RNA world". Science. 294 (5543): 797–99. doi:10.1126/science.1066315. PMID 11679654.

- ^ Fichou Y, Férec C (2006). "The potential of oligonucleotides for therapeutic applications". Trends in Biotechnology. 24 (12): 563–70. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.003. PMID 17045686.

External links

- RNA World website Link collection (structures, sequences, tools, journals)

- Nucleic Acid Database Images of DNA, RNA and complexes.