Kofun period

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

The Kofun period (古墳時代, Kofun jidai) is an era in the history of Japan from around 250 to 538. The word kofun is Japanese for the type of burial mounds dating from this era. The Kofun period follows the Yayoi period. The Kofun and the subsequent Asuka periods are sometimes referred to collectively as the Yamato period.

Generally, the Kofun period is divided from the Asuka period for its cultural differences. The Kofun period is illustrated by an animistic culture which existed prior to the introduction of Buddhism. Politically, the establishment of the Yamato court, and its expansion as allied states from Kyūshū to the Kantō are key factors in defining the period. Also, the Kofun period is the oldest era of recorded history in Japan. However, as the chronology of the historical sources are very much distorted, studies of this age require deliberate criticism and the aid of archaeology.

The archaeological record, and ancient Chinese sources, indicate that the various tribes and chiefdoms of Japan did not begin to coalesce into states until 300 AD, when large tombs began to appear while there were no contacts between western Japan and Korea or China. Some describe the "mysterious century" as a time of internecine warfare as various chiefdoms competed for hegemony on Kyūshū and Honshū.[1]

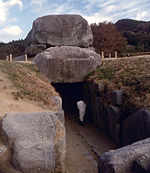

Kofun tombs

Kofun (古墳, "old tomb") are defined as the burial mounds built for the people of the ruling class during the 3rd to 7th centuries in Japan.[2] The Kofun period takes its name from these distinctive earthen mounds which are associated with the rich funerary rituals of the time. The mounds contained large stone burial chambers. Some are surrounded by moats.

Kofun came in many shapes, with round and square being the simplest. A distinct style is the keyhole-shaped kofun, with its square front and round back. Kofun range in size from several meters to over 400 meters in length.

Development of Kofun

The oldest Japanese Kofun is said to be Hokenoyama Kofun located in Sakurai, Nara, which dates to the late 3rd century. In Makimuku district of Sakurai, earlier keyhole kofuns (Hashihaka Kofun, Shibuya Mukaiyama Kofun) were built around the early 4th century. The trend of the keyhole kofun first spread from Yamato to Kawachi (where gigantic kofun such as Daisenryō Kofun), and then throughout the country (except for Tōhoku region) in the 5th century. Keyhole kofuns were also built in the Gaya confederacy of the Korean peninsula from the second half of the 5th century to the first half of the 6th century.[3][4][5] Whether the Keyhole tombs were an import from Korea to Japan or an export from Japan to Korea is debated.[5][6][7] "Still now, many Korean and Japanese scholars have concentrated on the issue of who are the owners of the keyhole-shaped tombs in Korean peninsula."

Keyhole kofun disappeared later in the 6th century, probably because of the drastic reformation which took place in the Yamato court; Nihon Shoki records the introduction of Buddhism at this time. The last two great kofun are the Imashirozuka kofun (length: 190m) of Osaka, which is believed by current scholars to be the tomb of Emperor Keitai, and the Iwatoyama kofun (length: 135m) of Fukuoka which was recorded in Fudoki of Chikugo to be the tomb of Iwai, the political archrival of Keitai.

Yamato court

While conventionally assigned to the period from 250 AD, the actual start of Yamato rule is disputed. The start of the court is also linked with the controversy of Yamataikoku and its fall. Regardless, it is generally agreed that Yamato rulers possessed keyhole kofun culture and held hegemony in Yamato up to the 4th century. The regional autonomy of local powers remained throughout the period, particularly in places such as Kibi (current Okayama prefecture), Izumo (current Shimane prefecture), Koshi (current Fukui and Niigata prefecture), Kenu (northern Kantō), Chikushi (northern Kyūshū), and Hi (central Kyūshū); it was only in the 6th century that the Yamato clans could be said to be dominant over the entire southern half of Japan. On the other hand, Yamato's relationships with China is likely to have begun in the late 4th century, according to the Book of Song.

The Yamato polity, which emerged by the late 5th century, was distinguished by powerful clans (豪族: Gōzoku). Each clan was headed by a patriarch (氏上: Ujikami) who performed sacred rites to the clan's kami to ensure the long-term welfare of the clan. Clan members were the aristocracy, and the kingly line that controlled the Yamato court was at its pinnacle.

The Kofun period of Japanese culture is also sometimes called the Yamato period by some Western scholars, since this local chieftainship arose to become the Imperial dynasty at the end of the Kofun period. Yamato and its dynasty however were just one rival polity among others throughout the Kofun era. Japanese archaeologists emphasise instead the fact that in the early half of the Kofun period other regional chieftainships, such as Kibi were in close contention for dominance or importance. The Tsukuriyama Kofun of Kibi is the fourth largest kofun in Japan.

The Yamato court ultimately exercised power over clans in Kyūshū and Honshū, bestowing titles, some hereditary, on clan chieftains. The Yamato name became synonymous with all of Japan as the Yamato rulers suppressed the clans and acquired agricultural lands. Based on Chinese models (including the adoption of the Chinese written language), they started to develop a central administration and an imperial court attended by subordinate clan chieftains but with no permanent capital. Japan's rulers of the time even petitioned the Chinese court for confirmation of royal titles.

The Yamato court had ties to the Gaya confederacy, called Mimana in Japanese. There is archaeological evidence from the Kofun tombs, which show similarities in form, art, and clothing of the depicted nobles. Based on the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, Japanese kokugaku historians claimed Gaya to be a colony of the Yamato state, a theory that is now widely rejected. More likely all these states were tributaries to the Chinese dynasties to some extent. However, Chinese scholars point to the Book of Song of the Liu Song Dynasty, written by the Chinese historian Shen Yue (441-513), presenting the sovereign of Japan as the suzerain of the Gaya Confederacy. This interpretation is also widely rejected even in Japan as there is no evidence of Japanese rule in Gaya or any other part of Korea.[8][9][10] Even more complicating is the Nihon Shoki referencing the Koreans to be the progenitor of Yamato. Due to these conflicting information nothing can be concluded for the book of Song or Nihon Shoki.

In recent years,many typical Japanese tumulus Kofun and jades was found in Baekje area and Gaya confederacy area.[3][4]

-

Kofun helmet, iron and gilt copper.

-

Kofun armor, iron plates sewn with leather.

-

Kofun armor.

-

Kofun helmet.

-

Kofun shield.

Territorial expansion of Yamato

In addition to archaeological findings indicating a local monarchy in the Kibi Province as an important rival, the legend of the 4th century Prince Yamato Takeru alludes to the borders of the Yamato and battlegrounds in the area. A frontier was obviously somewhere close to the later Izumo province (the eastern part of today's Shimane prefecture). Another frontier, in Kyūshū, was apparently somewhere north of today's Kumamoto prefecture. The legend specifically states that there was an eastern land in Honshū "whose people disobeyed the imperial court", against whom Yamato Takeru was sent to fight. That rivalling country may have been located rather close to the Yamato nucleus area itself, or relatively far away. The today Kai province is mentioned as one of the locations where prince Yamato Takeru sojourned in his said military expedition.

Northern frontier of this age was also explained in Kojiki as the legend of Shido Shogun's (四道将軍: Shoguns to four ways) expedition. Out of four shoguns, Ōbiko set northward to Koshi and his son Take Nunakawawake set to eastern states. The father moved east from northern Koshi while the son moved north on his way, and they finally met at Aizu (current western Fukushima). Although the legend itself is not likely to be a historical fact, Aizu is rather close to southern Tōhoku, where the north end of keyhole kofun culture as of late 4th century is located.

Ōkimi

During the Kofun period, a highly aristocratic society with militaristic rulers developed.

The Kofun period was a critical stage in Japan's evolution toward a more cohesive and recognized state. This society was most developed in the Kinai Region and the easternmost part of the Inland Sea. Japan's rulers of the time even petitioned the Chinese court for confirmation of royal titles.

While the rulers' titles are diplomatically King, they locally titled themselves as Ōkimi (Great King) during this period. Inscriptions in two swords, Inariyama Sword and Eta Funayama Sword had records of Amenoshita Shiroshimesu(治天下; "ruling of Heaven and Earth") and Ōkimi(大王) in common, to be a ruler that the bearers of these swords were subjected to. It reveals that rulers of this age also grasped religious authorities to justify their thrones through heavenly dignities. The title of Amenoshita Shiroshimesu Okimi was used up to 7th century, until being replaced by Tenno.

Clans of the Yamato Court

Many of the clans and local chieftains that made up the Yamato polity claimed descent from the imperial family or other tribal Gods. The archeological evidence for such clans is found in the Inariyama sword, on which the bearer recorded the names of his ancestors to claim its origin to Ōbiko (大彦) who was recorded in Nihon Shoki as a son of Emperor Kōgen. On the other hand, there are also a number of clans having origins in China or the Korean peninsula.

In the 5th century, the Kazuraki clan (葛城氏), descending from the legendary grandson of Emperor Kōgen, was the most prominent power in the court and intermarried with the imperial family. After Kazuraki declined in the late 5th century, the Ōtomo clan temporarily took its place. When Emperor Buretsu died with no apparent heir, it was Ōtomo no Kanamura who recommended Emperor Keitai, a very distant imperial relative who resided in Koshi Province, as the new monarch. However, Kanamura resigned due to the failure of his diplomatic policies, and the court was eventually controlled by the Mononobe and Soga clans at the beginning of the Asuka period.

Kofun society

Toraijin

Chinese and Korean immigrants who were naturalized in ancient Japan were called toraijin. They introduced many aspects of Chinese culture to Japan; valuing their knowledge and culture, the Yamato government gave preferential treatment to toraijin.

Chinese migration

Many important figures were also immigrants from China. Chinese immigrants also had considerable influence according to the Shinsen Shōjiroku,[11] which was used as a directory of aristocrats. Yamato Imperial Court had officially edited the directory in 815, and 163 Chinese clans were registered.

According to Nihon Shoki, the Hata clan, which was composed of descendants of Qin Shi Huang[12], arrived at Yamato in 403 (the fourteenth year of Oujin) leading the people of 120 provinces. According to the Shinsen Shōjiroku, the Hata clan were dispersed in various provinces during the reign of Emperor Nintoku and were made to undertake sericulture and the manufacturing of silk for the court. When the finance ministry was set up in Yamato Court, Hata Otsuchichi (秦大津父) was in charge of accounts as a minister of it.

In 409 (twentieth year of Oujin), Achi-no-Omi ancestor of the Yamato-Aya clan which was composed of also arrived with the people of 17 districts. According to the Shinsen Shōjiroku, Achi obtained the permission to establish the Province of Imaki. The Kawachi-no-Fumi clan, descendants of Gaozu of Han, introduced aspects of Chinese writing to the Yamato court.

The Takamuko clan is a descendant of Cao Cao. Takamuko-no-Kuromaro was a center member of Taika Reform.[13]

Korean migration

Among the many Korean immigrants who settled in Japan beginning in the 4th century, some came to be the progenitors of Japanese clans. According to Nihon Shoki, the oldest record of a Silla immigrant is Amenohiboko, a legendary prince of Silla who settled to Japan at the era of Emperor Suinin, perhaps around the 3rd or 4th century. Ironically, Amenohiboko is described in Nihon Shoki as a maternal predecessor of Empress Jingū, whose controversial legend says that she defeated Silla. This is highly inconsistent, as Jingū is said to have lived in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, and she is supposed to have died in 269 AD. These conflicting information make it difficult to understand these records.

Korean immigrants also include the Baekje royal family. King Muryeong of Baekje was born in 462, and left a son in Japan who settled there. King Muryeong was the grandfather of Japan's Emperor according the historical documents the Chronicals of Japan. In Emperor Ōjin's reign, Geunchogo of Baekje granted a large number of gifts and scholars to the Japanese emperor.[14] The elements of Chinese culture introduced to the Yamato Imperial Court are very important.[10] According to the book Shinsen Shōjiroku compiled in 815, a total 154 out of 1,182 noble families in the Kinai are on Honshū Island were regarded as people with Korean genealogy. The book specifically mentions 104 such families from Baekje, 41 from Goguryeo, 6 from Silla, and 3 from Gaya. [11] They might be families that moved to Japan between the years A.D.356-645.

Language

Chinese, Korean and Japanese wrote accounts of history mostly in Chinese characters, making original pronunciations difficult to trace.

While writing was largely unknown to the indigenous Japanese of this period, the literary skills of foreigners seem to have increasingly become appreciated by the elites of some Japanese regions. The Inariyama sword, made in either China (tentatively dated 471 or 531) contains Chinese-character inscriptions in styles used in China, leading to speculation that the owner, though claiming to be a Japanese aristocrat, might possibly actually have been an immigrant. [15]

Introduction of equine culture to Japan

Chinese chronicles make note that the horse was absent on the islands of Japan and they are first noted in the chronicles during the reign of Nintoku, most likely brought by China and Korean immigrants. The horse is one of the treasures presented when the king of Silla surrenders to Empress Jingū in the mythological record of Nihon Shoki.[16] The Nihon Shoki also states that Koreans were the ancestors to Empress Jingu, so both the Nihon Shoki and the Chinese chronicles relating to Japan is difficult to interpret. Irrigation, sericulture, and weaving were also brought to Japan by China and Korean immigrants who are mentioned in the ancient Japanese histories. For instance, the Hata clan, of Chinese origin, introduced sericulture.

The cavalry wore armour, carried swords and other weapons, and used advanced military methods like those of north-east Asia. Evidence of these advances is seen in funerary figures (called haniwa; literally, clay rings), found in thousands of kofun scattered throughout Japan. The most important of the haniwa were found in southern Honshū—especially the Kinai region around Nara—and northern Kyūshū. Haniwa grave offerings were made in numerous forms, such as horses, chickens, birds, fans, fish, houses, weapons, shields, sunshades, pillows, and male and female humans. Another funerary piece, the magatama, became one of the symbols of the power of the imperial house. Much of the material culture of the Kofun period is barely distinguishable from that of the contemporaneous southern Korean peninsula, demonstrating that at this time Japan was in close political and economic contact with continental Asia (especially with the southern dynasties of China) through Korea. Indeed, bronze mirrors cast from the same mould have been found on both sides of the Tsushima Strait.

Towards Asuka period

The Kofun period gave way to the Asuka period in mid-6th century AD by the introduction of Buddhism. The religion was officially introduced at the year 538, and this year is traditionally set for the epoch of the new period. Also, after the reunification of China by Sui Dynasty later in this century, Japan was deeply influenced by Chinese culture and consequently entered into a new cultural era.

Relations between the Yamato court and the Korean kingdoms

According to the Book of Song, a Chinese emperor appointed five kings of Wa to the position of ruler of Silla in 421,[17] but what is confusing is that immigrants from Silla are the progenitor of Japanese ruling class according to the Nihon Shoki. In addition, the book of Song and the book of Sui can not be possible because many of the states considered to be Japan's vassal such as Chinhan and Mahan did not exist in the same time period as the vassal king of Yamato. Also, Silla did not have official contact with the Song/Sui until the 6th century making this 4th to 5th century statement impossible. "As Egami (1964) notes, it may look very strange that the names of six or seven states listed in the self-claimed titles included Chin-han and Ma-han which had preceded, respectively, the states of Silla and Paekche. Perhaps the King of Wa had included the names of six or seven south Korean states in his title merely to boast of the extent of his rule. But Wa Kings could not have included the names of nonexistent states." Other historians also dispute Japan's theory, claiming there is no evidence of Japanese rule in Gaya or any other part of Korea.[18][9][10] Another problem with the book of Song and book of Sui is that many of the volumes of the books were missing and re-written later in a biased manner. It is difficult to make any sense of what the relationship was like in the past. Japan of the Kofun period was very positive towards the introduction of both Chinese culture and Korean culture.[19] Chinese and Korean immigrants played an important role in introducing elements of both Chinese civilization to early Japan.[20]

The special burial customs of the Goguryeo culture had an important influence on other cultures in Japan.[21] Decorated tombs and painted tumuli which date from the fifth century and later found in Japan are generally accepted as Korean peninsula exports to Japan. The Takamatsuzuka Tomb even has paintings of a woman dressed in distinctive clothes, similar to wall paintings from Goguryeo and Tang Dynasty China.[22][23] In addition, Chinese astrology was being introduced during this time.

Chinese and Korean records

According to the Book of Song, of the Liu Song Dynasty, the Emperor of China bestowed military sovereignty over Silla, Imna, Gaya, Chinhan, and Mahan on King Sai of Wa. However, this theory is widely rejected even in Japan as there is no evidence of Japanese rule in Gaya or any other part of Korea.[24][9][10] After the death of King Kō of Wa, his younger brother Bu acceeded to the throne; King Bu requested to have Baekje added to the list of protectorates included in the official title bestowed upon the King of Wa by mandate of the Emperor of China, but his title was only renewed as "Supervisor of All Military Affairs of the Six Countries of Wa, Silla, Imna, Gara, Chinhan, and Mahan, Great General Who Keeps Peace in the East, King of the Country of Wa."[25] This entire statement is impossible because Chinhan and Mahan did not exist in the same time period as Silla, Baekje when the vassal Kings of Yamato were suppose to rule. As Egami wrote in 1964 "But Wa Kings could not have included the names of nonexistent states." In addition, Silla did not have official contact with the Song/Sui until the 6th century making this 4 to 5th century claim not possible. Due to the lack of evidence, and the confusion of whether the Wa were the descendants of Koreans, none of this type of information is discernible.

According to the Book of Sui, Silla and Baekje needed assistance from Yamato Japan to continue military campaigns that had run out of steam.[26] According to the Samguk Sagi (Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms), Baekje and Silla sent their princes as hostages to the Yamato court in exchange for military support to continue their already-begun military campaigns; King Asin of Baekje sent his son Jeonji in 397[27] and King Silseong of Silla sent his son Misaheun in 402.[28][29] This interpretation is complicated by the fact that the rulers of Japan seems to be of Korean descent. Was the request for troops to a foreign nation or a familial co-operation.

One thing which can be stated positively is according to the Book of Sui, Silla and Baekje greatly valued relations with Wa (Japan) of the Kofun period, and the Korean kingdoms made diplomatic efforts to maintain their good standing with the Japanese. In exchange Japan received the advanced technological know how from Korea.[26]

See also

Notes

- ^ Farris (1998:7)

- ^ Kofun Culture, Charles T. Keally

- ^ a b Yoshida (1997:74-78)

- ^ a b The Hankyoreh 2001.9.6[1](in korean)

- ^ a b http://www.international.ucla.edu/korea/pdfs/YoshiiPaperFinal.pdf

- ^ Bogucki (1999:387)

- ^ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/04/080428-ancient-tomb.html

- ^ gias.snu.ac.kr/wthong/publication/paekche/eng/paekch_e.html

- ^ a b c Lee (1997:31-35)

- ^ a b c d Kōzō (1997:308-310) Cite error: The named reference "Kōzō" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Saeki (1981)

- ^ "Nihon no myōji 7000 ketsu seishi ruibetsu taikan Hata uji 日本の苗字7000傑 姓氏類別大観 秦氏". Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ^ "Nihon no myōji 7000 ketsu seishi ruibetsu taikan Takamuko uji 日本の苗字7000傑 姓氏類別大観 高向氏". Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ^ Kurano (1958:248-249)

- ^ Seeley (2000:19-23)

- ^ Sakamoto (1967:338-339)

- ^ Book of Song [2]

- ^ gias.snu.ac.kr/wthong/publication/paekche/eng/paekch_e.html

- ^ Imamura (1996)

- ^ Stearns (2001:56)

- ^ "Complex of Koguryo Tombs". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ^ Farris (1998:95)

- ^ MSN Encarta http://jp.encarta.msn.com/media_262538992_761577854_-1_1/content.html

- ^ gias.snu.ac.kr/wthong/publication/paekche/eng/paekch_e.html

- ^ Chinese History Record Book of Song : 宋書 列傳第五十七 夷蠻 : 詔除武使持節、都督倭新羅任那加羅秦韓慕韓六國諸軍事、安東大將軍、倭王。興死,弟武立,自稱使持節、都督倭百濟新羅任那加羅秦韓慕韓七國諸軍事、安東大將軍、倭國王

- ^ a b Chinese History Record Book of Sui : 隋書 東夷伝 第81巻列伝46 : 新羅、百濟皆以倭為大國,多珍物,並敬仰之,恆通使往來 [3][4] Cite error: The named reference "sui" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Korean History Record Samguk Sagi : 三國史記 新羅本紀 : 元年 三月 與倭國通好 以奈勿王子未斯欣爲質 [5]

- ^ Korean History Record Samguk Sagi : 三國史記 百済本紀 : 六年夏五月 王與倭國結好 以太子腆支爲質 秋七月大閱於漢水之南 [6]

- ^ [7][8]

References

- Bogucki, Peter (1999). The Origins of Human Society. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-5771-8112-3.

- Farris, William Wayne (1998). Sacred texts and buried treasures : issues in the historical archaeology of ancient Japan. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-1966-7.

- Imamura, Keiji (1996). Prehistoric Japan: New Perspectives on Insular East Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1852-0.

- Kōzō, Yamamura (1997). The Cambridge history of Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22354-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lee, Kenneth B (1997). Korea and East Asia : the story of a Phoenix. Praeger. ISBN 0-2759-5823-X.

- Kurano, Kenji (1958). Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei 1: Kojiki, Norito. Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-0006-0001-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Saeki, Arikiyo (1981). Shinsen Shōjiroku no Kenkyū (Honbun hen) (in Japanese). Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. ISBN 4-6420-2109-4.

- Sakamoto, Tarō (1967). Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei 67: Nihon Shoki. Vol. 1. Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-0006-0067-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Seeley, Christopher (2000). A history of writing in Japan. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2217-X.

- Stearns, Peter N. (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-3956-5237-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Yoshida, Takashi (1997). Nihon no tanjō (in Japanese). Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-0043-0510-1.

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

- Japan

This period is part of the Yamato period of Japanese History.

< Yayoi | History of Japan | Asuka period >