Graphic novel

A graphic novel is a type of comic book, usually with a lengthy and complex storyline similar to those of novels. It is also an item that people with no life argue over about what a graphic novel is versus a comic book. Those people are the ones that will die in their parents basements downloading pictures of Sarah Michelle Geller. The term also encompasses comic short story anthologies, and in some cases bound collections of previously published comic book series (more commonly referred to as trade paperbacks).

Graphic novels are typically bound in longer and more durable formats than familiar comic magazines, using the same materials and methods as printed books, and are generally sold in bookstores and specialty comic book shops rather than at newsstands.

Definition

The evolving term graphic novel is not strictly defined, and is sometimes used, controversially, to imply subjective distinctions in artistic quality between graphic novels and other kinds of comics. It suggests a story that has a beginning, middle and end, as opposed to an ongoing series with continuing characters; one that is outside the genres commonly associated with comic books, and that deals with more mature themes. It is sometimes applied to works that fit this description even though they are serialized in traditional comic book format. The term is commonly used to disassociate works from the juvenile or humorous connotations of the terms comics and comic book, implying that the work is more serious, mature, or literary than traditional comics. Following this reasoning, the French term Bande Dessinée is occasionally applied, by art historians and others schooled in fine arts, to dissociate comic books in the fine-art tradition from those of popular entertainment, even though in the French language the term has no such connotation and applies equally to all kinds of comic strips and books.

In the publishing trade, the term is sometimes extended to material that would not be considered a novel if produced in another medium. Collections of comic books that do not form a continuous story, anthologies or collections of loosely related pieces, and even non-fiction are stocked by libraries and bookstores as "graphic novels" (similar to the manner in which dramatic stories are included in "comic" books). It is also sometimes used to create a distinction between works created as stand-alone stories, in contrast to collections or compilations of a story arc from a comic book series published in book form.[1][2][3]

Whether manga, which has had a much longer history of both novel-like publishing and production of comics for adult audiences, should be included in the term is not always agreed upon. Likewise, in continental Europe, both original book-length stories such as La rivolta dei racchi (1967) by Guido Buzzeli,[4] and collections of comic strips have been commonly published in hardcover volumes, often called "albums", since the end of the 19th century (including Franco-Belgian comics series such as "The Adventures of Tintin" and "Lieutenant Blueberry", and Italian series such as "Corto Maltese").

History

As the exact definition of graphic novel is debatable, the origins of the artform itself are open to interpretation. Cave paintings may have told stories, and artists and artisans beginning in the Middle Ages produced tapestries and illuminated manuscripts that told or helped to tell narratives.

The first Western artist who interlocked lengthy writing with specific images was most likely William Blake (1757-1826). Blake created several books in which the pictures and the "storyline" are inseparable in his prophetic books such as Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Vala, or The Four Zoas.

The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck, the 1837 English translation of the 1833 Swiss publication Histoire de M. Vieux Bois by Swiss caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer, is the oldest recognized American example of comics used to this end.[5] The United States has also had a long tradition of collecting comic strips into book form. While these collections and longer-form comic books are not considered graphic novels even by modern standards, they are early steps in the development of the graphic novel.

Antecedents: 1920s to 1960s

The 1920s saw a revival of the medieval woodcut tradition, with Belgian Frans Masereel often cited as "the undisputed King" (Sabin, 291) of this revival. Among Masereel's works were Passionate Journey (1926, reissued 1985 as Passionate Journey: A Novel in 165 Woodcuts ISBN 0-87286-174-0). American Lynd Ward also worked in this tradition during the 1930s.

Other prototypical examples from this period include American Milt Gross' He Done Her Wrong (1930), a wordless comic published as a hardcover book, and Une Semaine de Bonté (1934), a novel in sequential images composed of collage by the surrealist painter Max Ernst. That same year, the first European comic-strip collections, called "albums", debuted with The Adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets by the Belgian Hergé.

In 1941, author/illustrator Virginia Lee Burton published "Calico the Wonder Horse, or the Saga of Stewy Stinker". Intrigued by her 9-year old son's fascination with comic books, she had taylored the book to his interest, creating an early graphic novel[6]

The 1940s saw the launching of Classics Illustrated, a comic-book series that primarily adapted notable, public domain novels into standalone comic books for young readers. The 1950s saw this format broadened, with popular movies being similarly adapted. By the 1960s, British publisher IPC had started to produce a pocket-sized comic-book line, the "Super Library", that featured war and spy stories told over roughly 130 pages.[citation needed]

In 1943 while imprisoned in Stalag V11A, Sergeant Robert Briggs drew a cartoon journal of his experiences from the start of the War till the time of his imprisonment. He intended it to amuse and keep his comrades spirits up. He remained imprisoned till the end of the war but his journal was smuggled out by an escaping officer and given to the Red Cross for safe-keeping. The Red Cross bound it as a token of honour and it was returned to him after the war ended. The journal was later published in 1985 by Arlington books under the title 'A Funny Kind Of War'. Despite it's posthumous publication, it remains the first instance of a cartoon diary being created. Its historical importance is emphasised by the fact that Robert Briggs created it during the war and not in hindsight. Its use of slang, frank depictions and descriptions of life during wartime and open racism is more accurate than many other war memoirs which leave out these details.

In 1950, St. John Publications produced the digest-sized, adult-oriented "picture novel" It Rhymes with Lust, a film noir-influenced slice of steeltown life starring a scheming, manipulative redhead named Rust. Touted as "an original full-length novel" on its cover, the 128-page digest by pseudonymous writer "Drake Waller" (Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller), penciler Matt Baker and inker Ray Osrin proved successful enough to lead to an unrelated second picture novel, The Case of the Winking Buddha by pulp novelist Manning Lee Stokes and illustrator Charles Raab.

By the late 1960s, American comic book creators were becoming more adventurous with the form. Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin self-published a 40-page, magazine-format comics novel, His Name is... Savage (Adventure House Press) in 1968 — the same year Marvel Comics published two issues of The Spectacular Spider-Man in a similar format. Columnist Steven Grant also argues that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's Doctor Strange story in Strange Tales #130-146, although published serially from 1965-1966, is "the first American graphic novel".[7]

Meanwhile, in continental Europe, the tradition of collecting serials of popular strips such as The Adventures of Tintin or Asterix had allowed a system to develop which saw works developed as long form narratives but pre-published as serials; in the 1970s this move in turn allowed creators to become marketable in their own right, auteurs capable of sustaining sales on the strength of their name.

By 1969, the author John Updike, who had entertained ideas of becoming a cartoonist in his youth, addressed the Bristol Literary Society, on "the death of the novel". Updike offered examples of new areas of exploration for novelists, declaring "I see no intrinsic reason why a doubly talented artist might not arise and create a comic strip novel masterpiece".[8]

Modern form and term

Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin's Blackmark (1971), a science fiction/sword-and-sorcery paperback published by Bantam Books, did not use the term originally; the back-cover blurb of the 30th-anniversary edition (ISBN 1-56097-456-7) calls it, retroactively, "the very first American graphic novel". The Academy of Comic Book Arts presented Kane with a special 1971 Shazam Award for what it called "his paperback comics novel". Whatever the nomenclature, Blackmark is a 119-page story of comic-book art, with captions and word balloons, published in a traditional book format. (It is also the first with an original heroic-adventure character conceived expressly for this form.)

Hyperbolic descriptions of longer comic books as "novels" appear on covers as early as the 1940s. Early issues of DC Comics' All-Flash Quarterly, for example, described their contents as "novel-length stories" and "full-length four chapter novels."[9] The Sinister House of Secret Love #2 (Jan. 1972), one of the same publisher's line of "52-Page Giants", specifically used the phrase "a graphic novel of gothic terror" on its cover.

The first six issues of writer-artist Jack Katz's 1974 Comics and Comix Co. series The First Kingdom were collected as a trade paperback (Pocket Books, March 1978, ISBN 0-671-79016-1),[10] which described itself as "the first graphic novel". Issues of the comic had described themselves as "graphic prose", or simply as a novel.

European creators were also experimenting with the longer narrative in comics form. In the United Kingdom, Raymond Briggs was producing works such as Father Christmas (1972) and The Snowman (1978), which he himself described as being from the "bottomless abyss of strip cartooning", although they, along with such other Briggs works as the more mature When the Wind Blows (1982), have been re-marketed as graphic novels in the wake of the term's popularity. Briggs notes, however, "I don't know if I like that term too much".[11]

First self proclaimed graphic novels: 1976-8

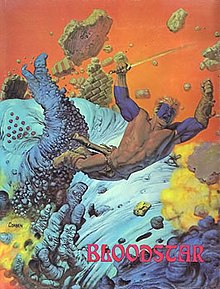

Regardless, the term appeared in print in 1976 in connection with three separate works. Bloodstar by Richard Corben (adapted from a story by Robert E. Howard) used the term to define itself on its dust jacket and introduction. George Metzger's Beyond Time and Again, serialized in underground comics from 1967-72, was subtitled "A Graphic Novel" on the inside title page when collected as a 48-page, black-and-white, hardcover book published by Kyle & Wheary.[12] And the digest-sized Chandler: Red Tide (1976) by Jim Steranko, designed to be sold on newsstands, used the term "graphic novel" in its introduction and "a visual novel" on its cover, although Chandler is more commonly considered an illustrated novel than a work of comics.

The following year, Terry Nantier, who had spent his teenage years living in Paris, returned to the United States and formed Flying Buttress Publications, later to incorporate as NBM Publishing (Nantier, Beall, Minoustchine), and published Racket Rumba, a 50-page spoof of the noir-detective genre, written and drawn by the single-name French artist Loro. Nantier followed this with Enki Bilal's The Call of the Stars. The company marketed these works as "graphic albums"[13]

Similarly, Sabre: Slow Fade of an Endangered Species by writer Don McGregor and artist Paul Gulacy (Eclipse Books, Aug. 1978) — the first graphic novel sold in the newly created "direct market" of United States comic-book shops — was called a "graphic album" by the author in interviews, though the publisher dubbed it a "comic novel" on its credits page. "Graphic album" was also the term used the following year by Gene Day for his hardcover short-story collection Future Day (Flying Buttress Press).

Another early graphic novel, though it carried no self-description, was The Silver Surfer (Simon & Schuster/Fireside Books, August 1978), by Marvel Comics' Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Significantly, this was published by a traditional book publisher and distributed through bookstores, as was cartoonist Jules Feiffer's Tantrum (Alfred A. Knopf, 1979)[14] described on its dustjacket as a "novel-in-pictures".

Adoption of the term

The term "graphic novel" began to grow in popularity months after it appeared on the cover of the trade paperback edition (though not the hardcover edition) of Will Eisner's groundbreaking A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories (Oct. 1978). This collection of short stories was a mature, complex work focusing on the lives of ordinary people in the real world, and the term "graphic novel" was intended to distinguish it from traditional comic books, with which it shared a storytelling medium. This established both a new book-publishing term and a distinct category. Eisner cited Lynd Ward's 1930s woodcuts (see above) as an inspiration.

The critical and commercial success of A Contract with God helped to establish the term "graphic novel" in common usage, and many sources have incorrectly credited Eisner with being the first to use it. In fact, it was used as early as November 1964 by Richard Kyle in CAPA-ALPHA #2, a newsletter published by the Comic Amateur Press Alliance, and again in Kyle's Fantasy Illustrated #5 (Spring 1966). Kyle, inspired by European and Japanese comic albums, used the label to designate comics of an artistically "serious" sort.[15]

One of the earliest contemporaneous applications of the term post-Eisner came in 1979, when Blackmark's sequel — published a year after A Contract with God though written and drawn in the early 1970s — was labeled a "graphic novel" on the cover of Marvel Comics' black-and-white comics magazine Marvel Preview #17 (Winter 1979), where Blackmark: The Mind Demons premiered — its 117-page contents intact, but its panel-layout reconfigured to fit 62 pages.

Dave Sim's comic book Cerebus had been launched as a funny-animal Conan parody in 1977, but in 1979 Sim announced[citation needed] it was to be a 300-issue novel telling the hero's complete life story. In England, Bryan Talbot wrote and drew The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, described by Warren Ellis as "probably the single most influential graphic novel to have come out of Britain to date".[16] Like Sim, Talbot also began by serializing the story, originally in Near Myths (1978), before it was published as a three-volume graphic-novel series from 1982-87.

Following this, Marvel from 1982 to 1988 published the Marvel Graphic Novel line of 10"x7" trade paperbacks — although numbering them like comic books, from #1 (Jim Starlin's The Death of Captain Marvel) to #35 (Dennis O'Neil, Mike Kaluta, and Russ Heath's Hitler's Astrologer, starring the radio and pulp fiction character the Shadow, and, uniquely for this line, released in hardcover). Marvel commissioned original graphic novels from such creators as John Byrne, J. M. DeMatteis, Steve Gerber, graphic-novel pioneer McGregor, Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz, Walt Simonson, Charles Vess, and Bernie Wrightson. While most of these starred Marvel superheroes, others, such as Rick Veitch's Heartburst featured original SF/fantasy characters; others still, such as John J. Muth's Dracula, featured adaptations of literary stories or characters; and one, Sam Glanzman's A Sailor's Story, was a true-life, World War II naval tale.

In England, Titan Books held the license to reprint strips from 2000 AD, including Judge Dredd, beginning in 1981, and Robo-Hunter, 1982. The company also published British collections of American graphic novels — including Swamp Thing, notable for being printed in black and white rather than in color as originally — and of British newspaper strips, including Modesty Blaise and Garth. Igor Goldkind was the marketing consultant who worked at Titan and moved to 2000 AD and helped to popularize the term "graphic novel" as a way to help sell the trade paperbacks they were publishing. He admits that he "stole the term outright from Will Eisner" and his contribution was to "take the badge (today it's called a 'brand') and explain it, contextualise it and sell it convincingly enough so that bookshop keepers, book distributors and the book trade would accept a new category of 'spine-fiction' on their bookshelves".[17]

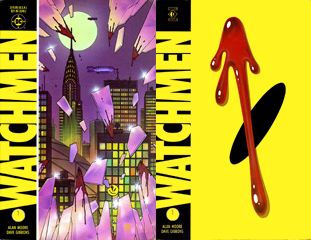

DC Comics likewise began collecting series and published them in book format. Two such collections garnered considerable media attention, and they, along with Art Spiegelman's Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus (1986), helped establish both the term and the concept of graphic novels in the minds of the mainstream public. These were Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), a collection of Frank Miller's four-part comic-book series featuring an older Batman faced with the problems of a dystopian future; and Watchmen (1987), a collection of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' 12-issue limited series in which Moore notes he "set out to explore, amongst other things, the dynamics of power in a post-Hiroshima world"..[18]

These works and others were reviewed in newspapers and magazines, leading to such increased coverage that the headline "Comics aren't just for kids anymore" became widely regarded by fans as a mainstream-press cliché.[19] Variations on the term can be seen in the Harvard Independent[20] and at Poynter Online.[21] Regardless, the mainstream coverage led to increased sales, with Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, for example, lasting 40 weeks on a UK best-seller lists.[22]

Criticism of the term

Some in the comics community have objected to the term "graphic novel" on the grounds that it is unnecessary, or that its usage has been corrupted by commercial interests. Writer Alan Moore believes, "It's a marketing term ... that I never had any sympathy with. The term 'comic' does just as well for me. ... The problem is that 'graphic novel' just came to mean 'expensive comic book' and so what you'd get is people like DC Comics or Marvel comics — because 'graphic novels' were getting some attention, they'd stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel...."[23]

Author Daniel Raeburn wrote "I snicker at the neologism first for its insecure pretension — the literary equivalent of calling a garbage man a 'sanitation engineer' — and second because a 'graphic novel' is in fact the very thing it is ashamed to admit: a comic book, rather than a comic pamphlet or comic magazine."[24]

Writer Neil Gaiman, responding to a claim that he does not write comic books but graphic novels, said the commenter "meant it as a compliment, I suppose. But all of a sudden I felt like someone who'd been informed that she wasn't actually a hooker; that in fact she was a lady of the evening."[25] Comedian and comic book fan Robin Williams joked, "'Is that a comic book? No! It's a graphic novel! Is that porn? No! It's adult entertainment!'"[26]

Critic Douglas Wolk quipped: "The question I got asked most often this year: 'What's the difference between "comics" and "graphic novels"?' My answer: 'The binding.'"[27] Responding to Wolk's comment, Bone creator Jeff Smith said, "I kind of like that answer. Because 'graphic novel'... I don't like that name. It's trying too hard. It is a comic book. But there is a difference. And the difference is, a graphic novel is a novel in the sense that there is a beginning, a middle and an end."[28]

Some alternative cartoonists have coined their own terms to describe extended comics narratives. The cover of Daniel Clowes' Ice Haven (2001) describes the book as "a comic-strip novel", with Clowes having noted that he "never saw anything wrong with the comic book".[29] Similarly, the cover of Craig Thompson's Blankets calls it "an illustrated novel." Similarly, When The Comics Journal asked the cartoonist Seth why he added the subtitle "A Picture Novella" to his comic It's a Good Life, If You Don't Weaken, he responded, "I could have just put 'a comic book'... It goes without saying that I didn't want to use the term graphic novel. I just don't like that term".[30]

Quotes

Charles McGrath (former editor, The New York Times Book Review) in The New York Times: "Some of the better-known graphic novels are published not by comics companies at all but by mainstream publishing houses — by Pantheon, in particular — and have put up mainstream sales numbers. Persepolis, for example, Marjane Satrapi's charming, poignant story, drawn in small black-and-white panels that evoke Persian miniatures, about a young girl growing up in Iran and her family's suffering following the 1979 Islamic revolution, has sold 450,000 copies worldwide so far; Jimmy Corrigan sold 100,000 in hardback...."[31]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Gertler, Nat (2004). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Creating a Graphic Novel. Alpha Books. ISBN 1592572332.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Friday, Brad. "A few graphic novel gift ideas…". CMJ.com staff blogs. CMJ.com. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help) - ^ Kaplan, Arie (2006). Masters of the Comic Book Universe Revealed!. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1556526334.

- ^ Buzzeli's work was presented at the International Comics Festival of Lucca in 1967, with a complete edition published in 1970 before being serialised in French magazine Charlie Mensuel. "Dino Buzzati 1965-1975" (http (Italian)). Associazione Guido Buzzelli. 2004. Retrieved 2006-06-21., Domingos Isabelinho (2004). "The Ghost of a Character: The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James" (http). Indy Magazine. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ^ Collector Times (n.d.): "TheComicsBooks.com - The History of Comic Books: See You in the Funny Pages"

- ^ Publisher's Note in the 1997 Houghton Mifflin Company edition, ISBN 039585735X

- ^ Grant, Steven (December 28, 2005). "The First Graphic Novel". Comicbookresources.com. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gravett, Paul (2005). Graphic Novels: Stories To Change Your Life (1st ed.). Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 1-84513-068-5.

- ^ Grand Comics Database: All-Flash (DC, 1941). See Issues #2-10.

- ^ Grand Comics Database: The First Kingdom

- ^ Nicholas, Wroe (December 18, 2004). "Bloomin' Christmas". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Comics historian R.C. Harvey noted this fact in a letter to Andrew Arnold, Time columnist, in response to Arnold's column celebrating the 25th anniversary of the term. Andrew Arnold (Nov. 21, 2003). "A Graphic Literature Library". Time. Retrieved 2006-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "America's First Graphic Novel Publisher". NBM Publishing official home page. Retrieved 2006-06-21.

- ^ Wellington (New Zealand) Public Libraries: "Tantrum / Jules Feiffer". Note: Though this library source lists Tantrum in its children's catalog, the mature-audience story contains male and female nudity and sexual situations.

- ^ Gravett, Graphic Novels, p. 3.

- ^ Warren Ellis. "Book Review: The Adventures of Luther Arkwright" (html). artbomb.net. Retrieved 2006-06-21.

- ^ 2006 interview with Igor Goldkind

- ^ Moore letter, Cerebus, no. 217 (April 1997). Aardvark Vanaheim.

- ^ Comic-book writer J.M. DeMatteis interview in "Caught in The Nexus: J.M. DeMatteis". The Nexus. February 19, 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wilson, Shane (March 18, 2004). "Holy Pretension, Batman!". Harvard Independent. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hammond, Margot (September 2, 2004). "Comic Books for Big People". Poynter Online. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Campbell, Eddie (2001). Alec:How to be an Artist (1st ed.). Eddie Campbell Comics. p. 96. ISBN 0-9577896-3-7.

- ^ Kavanagh, Barry (October 17, 2000). "The Alan Moore Interview". Blather.net. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chris Ware (Monographics Series) (2004), p. 110

- ^ Bender, Hy (1999), The Sandman Companion, Vertigo, ISBN 1-56389-644-3

- ^ Jeff Otto (2006-06-26). "Robin Williams, Joker?". IGN. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ^ "Pilgrim, Exit Wounds Top Second Annual PWCW Critics' Poll,", PW Comics Week, January 1, 2008.

- ^ Vaneta Rogers, Behind the Page: Jeff Smith, Part Two, Newsarama, February 26, 2008.

- ^ Bushell, Laura (July 21, 2005). "The Ghost World creator does it again". BBC - Collective. Retrieved 2006-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ ""Seth", by Gary Groth". The Comics Journal #193. 1997. pp. 58–93.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McGrath, Charles (July 11, 2004). "Not Funnies". The New York Times. p. 24. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite news}}:|section=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Arnold, Andrew D. "The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary", Time, November 14, 2003

- Tychinski, Stan. Brodart.com: "A Brief History of the Graphic Novel" (n.d., 2004)

- Couch, Chris. "The Publication and Formats of Comics, Graphic Novels, and Tankobon", Image & Narrative #1 (Dec. 2000)

- Sabin, Roger. Adult Comics: An Introduction(Routledge New Accents Library Collection, 2005) ISBN 0415291399, ISBN 978-0415291392

- Comicartville Library: "Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could", by Ken Quattro

External links

- The Big Comic Book DataBase

- Recommended Graphic Novels for Public Libraries

- Graphic Novels and Comic Trade Paperbacks - An Annotated List

- UNCA Graphic Novels - bibliography of GNs and articles about them

- FIST: Fast, Inexpensive, Simple & Tiny by Maj Dan Ward, Maj Chris Quaid and Maj Gabe Mounce, USAF; and Jim Elmore. A two-page "graphic article" published in Defense AT&L, a military technology journal.