Buzz Aldrin

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Buzz Aldrin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Status | Retired |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Fighter pilot |

| Space career | |

| Astronaut | |

| Rank | Colonel, USAF |

Time in space | 12 days, 1 hour and 52 minutes |

| Selection | 1963 NASA Group |

| Missions | Gemini 12, Apollo 11 |

Mission insignia | |

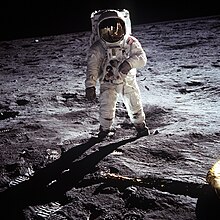

Buzz Aldrin (born Edwin Eugene Aldrin, Jr., January 20, 1930) is an American aviator and astronaut who was the Lunar Module pilot on Apollo 11, the first lunar landing. He and mission commander Neil Armstrong were the first persons to land on the Moon; shortly afterward he became the second man to set foot on the Moon.

Biography

Aldrin was born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey,[1] to Edwin Eugene Aldrin, Sr., a career military man, and his wife Marion Moon.[2] He is of Scottish and Swedish ancestry.[3] After graduating from Montclair High School in Montclair, New Jersey in 1946,[4] Aldrin went to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The nickname "Buzz" originated in childhood: his little sister mispronounced "brother" as "buzzer", and this was shortened to Buzz. Aldrin made it his legal first name in 1988.[5][6]

Military career

Aldrin graduated third in his class at West Point in 1951 with a B.S. degree. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force and served as a jet fighter pilot during the Korean War. He flew 66 combat missions in F-86 Sabres and shot down two Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 aircraft. The June 8, 1953 issue of LIFE magazine featured gun camera photos taken by Aldrin of one of the Russian pilots ejecting from his damaged aircraft.

After the war, Aldrin was assigned as an aerial gunnery instructor at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, and next was an aide at the U.S. Air Force Academy. He flew F-100 Super Sabres as a flight commander at Bitburg, Germany in the 22nd Fighter Squadron. Aldrin then earned his D.Sc. degree in Astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His graduate thesis was Line-of-sight guidance techniques for manned orbital rendezvous. On completion of his doctorate, he was assigned to the Gemini Target Office of the Air Force Space Systems Division in Los Angeles, and finally to the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School Edwards Air Force Base.

Aldrin was selected as part of the third group of NASA astronauts in October 1963. After the deaths of the original Gemini 9 prime crew, Elliot See and Charles Bassett, Aldrin was promoted to back-up crew for the mission. The main objective of the revised mission (Gemini 9A) was to rendezvous and dock with a target vehicle, but when this failed, Aldrin improvised an effective exercise for the craft to rendezvous with a co-ordinate in space. He was confirmed as pilot on Gemini 12, the last Gemini mission and the last chance to prove methods for EVA. He utilized revolutionary techniques during training for that mission, including neutrally-buoyant underwater training. Such techniques are still used today. Aldrin set a record for extra-vehicular activity and proved that astronauts could work outside the spacecraft.

Much has been said about Aldrin's desire at the time to be the first astronaut to walk on the moon.[7] Differing NASA accounts have it that he had originally been proposed as the first, but the configuration of the lunar module was changed, or that protocol demanded that the commander (Armstrong) be the first. (In addition, in a March 1969 meeting between senior NASA personnel Deke Slayton, George Low, Bob Gilruth, and Chris Kraft, it was suggested that Armstrong be the first partly because Armstrong was seen as not having a large ego.)[8] Nonetheless, Aldrin may have had an even more singular contribution. Armstrong's famous "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed," were the first words intentionally spoken to Mission Control and the world from the lunar surface. However, the actual first words ever spoken on the moon as heard, at approximately 20:17:39 UTC on July 20 1969, were very likely Lunar Module Pilot Aldrin's "Contact Light... Okay, Engine Stop" (although Armstrong leaves open whether he said "Shutdown" first.)[9][10][11]

Aldrin is a Presbyterian, and is known for his statements about God. After landing on the moon, Aldrin radioed earth with these words: "I'd like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way." He received Communion on the surface of the Moon, but kept it secret because of a lawsuit brought by Madalyn Murray O'Hair over the reading of Genesis on Apollo 8.[12] Aldrin, a church elder, used a pastor's home Communion kit given to him by Dean Woodruff and recited words used by his pastor at Webster Presbyterian Church. [13][14] Webster Presbyterian Church, a local congregation in Webster, Texas (a Houston suburb near the Johnson Space Center) possesses the chalice used for communion on the moon, and commemorates the event annually on the Sunday closest to July 20.[15]

Aldrin is represented by the Executive Speakers Bureau of Memphis, Tennessee, and receives between $30,000-$50,000 per appearance.[16]

Aldrin Cycler

In 1985, Aldrin invented a special spacecraft trajectory now known as the Aldrin cycler[17][18]. A spacecraft traveling on an Aldrin cycler trajectory would pass near the planets Earth and Mars on a regular (cyclic) basis. The Aldrin cycler is an example of a Mars cycler (of which there are others).

Retirement

In March 1972, Aldrin retired from active duty after 21 years of service, and returned to the Air Force in a managerial role, but his career was blighted by personal problems. His 1973 autobiography Return to Earth provides an account of his struggles with clinical depression and alcoholism in the years following his NASA career. His life improved considerably when he recognized and sought treatment for his problems, and with his marriage to Lois Aldrin. Since retiring from NASA, he has continued to promote space exploration, including producing a computer strategy game called "Buzz Aldrin's Race into Space" (1992).

Personal life

Aldrin has been married three times. His first wife was Joan Archer, with whom he had three children, James, Janice, and Andrew. His second wife was Beverly Zile. Aldrin married his current wife, Lois Driggs Cannon, on Valentine's Day in 1988. He is also a grandfather. [19]

Honors and roles in the arts

- Buzz Aldrin made a guest star appearance in an episode of animated sitcom The Simpsons entitled "Deep Space Homer", in which the main character, Homer Simpson, signs up to NASA as their first "Average Joe" astronaut. Aldrin displayed a good sense of humor about his status as second man on the moon, proclaiming "Second comes right after first!", while his introduction to Homer is met with absolute non-recognition.

- The crater Aldrin on the Moon near the Apollo 11 landing site and Asteroid 6470 Aldrin[20] are named in his honor.

- In 1967, Aldrin received an Honorary Doctorate of Science from Gustavus Adolphus College.

- In 2001, President Bush appointed Aldrin to the Commission on the Future of the United States Aerospace Industry.[21][22]

- Aldrin received the 2003 Humanitarian Award from Variety, the Children's Charity, which, according to the organization, "is given to an individual who has shown unusual understanding, empathy, and devotion to mankind."[23]

- Aldrin is on the National Space Society's Board of Governors, and has served as the organization's Chairman; an inductee of the Astronaut Hall of Fame; and a member of The Planetary Society, with Aldrin's pre-recorded voice appearing on nearly every episode of the Society's Planetary Radio.

- The British television comedy group Monty Python, on October 20 1970, ran an episode called the "Buzz Aldrin Show" with a few references to him and his photo superimposed over the credits while The Star-Spangled Banner was played.

- Cliff Robertson played Aldrin in the 1976 TV-movie Return to Earth based on Aldrin's own memoir.

- In September 2008, Aldrin announced that he was writing a new memoir, entitled "Magnificent Desolation," about his astronaut career and he and his wife's struggle with an addiction to plastic surgery. [24]

- Aldrin was portrayed by Larry Williams in the 1995 film Apollo 13.

- Aldrin played the role of Reverend Woodruff in the 1996 TV movie Apollo 11, while his own character was played by Xander Berkeley, who had previously played the small role of Henry Hurt in Apollo 13.

- The matter of who would make the first step on the moon was dramatized in the 1998 miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, based on Andrew Chaikin's book A Man on the Moon, in which Aldrin was portrayed by Bryan Cranston.

- The popular space ranger character Buzz Lightyear, from Pixar's Toy Story movie series, is named after him, largely due to the suggestion of the film's makers that he has "the coolest name of any astronaut". Aldrin acknowledged the tribute when he pulled a Buzz Lightyear doll out during a speech at NASA, to rapturous cheers (a clip of which can be found on the Toy Story 10th Anniversary DVD).

- He appeared in a 2003 interview with Ali G in the British comedy series Ali G in da USA, during which Ali G referred to him as Buzz Lightyear and asked him if he thought man would ever walk on the sun.

- Aldrin voiced himself in a 1999 episode of Disney's Recess.

- Aldrin collaborated with science fiction author John Barnes to write Encounter With Tiber and The Return.

- In 2006, the Space Foundation awarded Aldrin its highest honor, the General James E. Hill Lifetime Space Achievement Award,[25] which is presented annually to recognize outstanding individuals who have distinguished themselves through lifetime contributions to the welfare or betterment of humankind through the exploration, development and use of space, or the use of space technology, information, themes or resources in academic, cultural, industrial or other pursuits of broad benefit to humanity.

- In a 2006 episode of NUMB3RS titled "Killer Chat", Aldrin plays himself and is seen at the end escorting Larry from the FBI headquarters on his way to his launch to the International Space Station.

- On December 26 2006, UK TV channel Channel 4 transmitted a 50 minute opera by British composer Jonathan Dove called Man on the Moon, especially made for television. It tells the story of Aldrin's trip to the moon interleaved with the effects the experience had on him and his marriage. Aldrin was played by Nathan Gunn, and Joan Aldrin by Patricia Racette.

- In 2007, Aldrin participated in the book and documentary In the Shadow of the Moon.

- He plays himself in the 3-D animated film Fly Me to the Moon.

- The story of Apollo 11, through the eyes of Aldrin, was recently reimagined as a musical. 'Moon Landing' was written, composed and directed by Stephen Edwards, and performed at Derby Playhouse, and included inventive scenery, including a floating shuttle capsule.

- In 1986, after the Challenger explosion, he appeared in the Punky Brewster episode "Accidents Happen" as himself to encourage a disheartened Punky to continue pursuing her dream of becoming an astronaut.

- Aldrin is the model for the MTV Video Music Award moonman. [5]

- Psychedelic rock band Bardo Pond released a track called Aldrin on their Lapsed LP

- Template:HWOF sentence

- Aldrin was interviewed on the July 31st 2008 episode of The Colbert Report, promoting the film Fly Me to the Moon.

Media

Aldrin is one of the astronauts featured in the book and documentary In the Shadow of the Moon, and the documentary "The Wonder of it All."

Hoax allegations

In 2005, while being interviewed for a documentary titled First on the Moon: The Untold Story, Aldrin told an interviewer that they saw an unidentified flying object. Aldrin told David Morrison, an NAI Senior Scientist, that the documentary cut the crew's conclusion that they were probably seeing one of four detached spacecraft adapter panels. The crew was told that their S-IVB upper stage was 6,000 miles away. However, the panels were jettisoned before the S-IVB made its separation maneuver, so this panel would closely follow the Apollo 11 spacecraft until its first midcourse correction.[26] When Aldrin appeared on The Howard Stern Show on August 15, 2007, Stern asked him about the supposed UFO sighting. Aldrin confirmed that there was no such sighting of anything deemed extraterrestrial, and said they were and are "99.9 percent" sure that the object was the detached panel.[27][28][29][30]

Interviewed by the Science Channel, Aldrin mentioned seeing unidentified objects, and he claims his words were taken out of context; he asked the Science Channel to clarify to viewers he did not see a UFO, but they refused.[31]

On September 9, 2002, filmmaker Bart Sibrel, a proponent of the Apollo moon landing hoax theory, confronted Aldrin outside a Beverly Hills, California hotel. Sibrel said "You're the one who said you walked on the moon and you didn't" and called Aldrin "a coward, a liar, and a thief." Aldrin punched Sibrel in the face. Beverly Hills police and the city's prosecutor declined to file charges. Sibrel suffered no permanent injuries.[32]

Notes

- ^ Hansen, James R. (2005). First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. Simon & Schuster. p. 348."Buzz Aldrin's birthplace has frequently been given to be Montclair, New Jersey. In fact, he was born on the Glen Ridge wing of a hospital whose central body rested in Montclair. His birth certificate lists Glen Ridge as his birthplace."

- ^ BuzzAldrin.com - About Buzz Aldrin

- ^ http://www.burkes-peerage.net/articles/scotland/saal7.aspx

- ^ "AdirondackDailyEnterprise.com Archives" ([dead link]).

- ^ a b "BuzzAldrin.com - About Buzz Aldrin: FAQ" ([dead link]). Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Buzz Aldrin Quick Facts - Quick Facts - MSN Encarta

- ^ Expeditions to the Moon, chapter 8, p. 7.

- ^ Hansen, chapter 25.

- ^ Jones. "The First Lunar Landing, time 1:02:45". Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ^ "Mission Transcripts, Apollo 11 AS11 PA0.pdf". Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Mission Commentary 7-20-69 CDT 15:15 - GET 102:43 - TAPE 307/1".

- ^ Chaikin, Andrew. A Man On The Moon. p 204

- ^ ("First on the Moon — A Voyage with Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr", written with Gene Farmer and Dora Jane Hamblin, epilogue by Arthur C. Clarke, Michael Joseph Ltd, London (1970), page 251).

- ^ Hillner, Jennifer (2007-01-24). "Sundance 2007: Buzz Aldrin Speaks". Table of Malcontents - Wired Blogs. Wired. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Webster Presbyterian Church Lunar Communion service" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ^ Buzz Aldrin Executive Speaker's Bureau

- ^ Aldrin, E. E., "Cyclic Trajectory Concepts," SAIC presentation to the Interplanetary Rapid Transit Study Meeting, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, October 1985.

- ^ Byrnes, D. V., Longuski, J. M., and Aldrin, B.,"Cycler Orbit Between Earth and Mars," Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, Vol. 30, No. 3, May-June 1993, pp. 334-336.

- ^ Read, Kimberly (2005-01-04). "Buzz Aldrin". http://bipolar.about.com. http://about.com. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink=,|publisher=, and|work=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Discovery Circumstances: Numbered Minor Planets (5001)-(10000): 6470 Aldrin". IAU: Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ^ Personnel Announcements - August 22, 2001 White House Press Release naming the Presidential Appointees for the commission.

- ^ [1] - This sources states he was appointed in 2002, although according to the August 22, 2001 Press Release, it was 2001.

- ^ "Variety International Humanitarian Awards". Variety, the Children's Charity. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Former astronaut Buzz Aldrin working on memoir".

- ^ http://www.nationalspacesymposium.org/symposium-awards

- ^ "Apollo 11 Mission Op Report" (PDF).

- ^ "NASA Ask an Astrobiologist".

- ^ "Daily Record Article".

- ^ "Site containing a transcript of the UFO segment of the Untold Story documentary".

- ^ "A link to The Science Channel scheduling info for cited documentary containing Aldrin's UFO comments".

- ^ Morrison, David (2009). "UFOs and Aliens in Space". Skeptical Inquirer. 33 (1): 30–31.

- ^ "Ex-astronaut escapes assault charge". BBC News. 2002-09-21. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

External links

- Official website

- Buzz Aldrin's Official NASA Biography

- A February 2009 BBC News item about Buzz Aldrin's moon memories, looking forward to the 40th anniversary of the first moon landing

- 10 Questions for Buzz Aldrin on Time.com (a division of Time Magazine)

- Buzz Aldrin Honored as an Ambassador of Exploration

- Pictures of Buzz and Lois Aldrin with Ben Solms and Aimee de Heeren

- Buzz Aldrin's Roadmap to Mars (Popular Mechanics, December 2005)

- "Satellite of solitude" by Buzz Aldrin: an article in which Aldrin describes what it was like to walk on the Moon, Cosmos science magazine

- "SWINDLE Interview" SWINDLE Magazine interview with Buzz Aldrin

- "Signature of Buzz Aldrin" Signature of Buzz Aldrin - Reaching For The Moon

- "American Moon" Cute song from the Apollo 11 era by Bob Crewe and recorded with Bobby Dimple, Lunar Ladies Chorus, Lipple Kutie Kids, Hutch Davie Diggers Band - American Moon (from The Heart's Delight Follies '69)

Template:Astronaut Group 3 Footer

Template:Persondata {{subst:#if:Aldrin, Buzz|}} [[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1930}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:living}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1930 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:living}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- 1966 in space exploration

- 1969 in space exploration

- People from Essex County, New Jersey

- American astronauts

- People who have walked on the Moon

- United States Air Force officers

- American aviators

- American military personnel of the Korean War

- Harmon Trophy winners

- United States Astronaut Hall of Fame inductees

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees

- People from Montclair, New Jersey

- American Presbyterians

- Scottish Americans

- Swedish Americans

- American science fiction writers

- Living people

- Living deaths