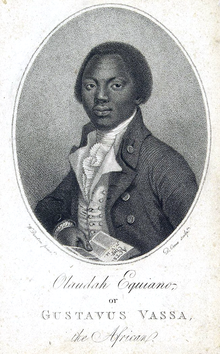

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1745 Essaka, Benin Empire |

| Died | 31 March 1797 (age 52) |

| Other names | Vassa, Gustavus |

| Occupation(s) | Slave, Explorer, Writer, seaman |

| Known for | Influence over British lawmakers to abolish the slave trade; autobiography |

| Spouse | Susannah Cullen |

| Children | Joanna Vassa and Anna Maria Vassa |

Olaudah Equiano [1](c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), also known as Gustavus Vassa, was one of the most prominent Africans involved in the British movement for the abolition of the slave trade. His autobiography depicted the horrors of slavery and helped influence British lawmakers to abolish the slave trade through the Slave Trade Act of 1807. Despite his enslavement as a young man, he purchased his freedom and worked as a seaman, merchant and explorer in South America, the Caribbean, the Arctic, the American colonies and the United Kingdom.

Early life

By his own account, Olaudah Equiano began his early life in the region of "Assaka" (in his spelling) near the River Niger. He was believed to be an Ibo. At the age of eleven, he was kidnapped with a younger sister by kinsmen and forced into domestic slavery in another native village. The region had a chieftain hierarchy tied to slavery. Until then Equiano had never seen a European white man.[2][3] Equiano lived with five brothers and a sister, and was part of a large family before he and his sister were kidnapped. He was the youngest son with one younger sister.

Enslavement

Equiano and his sister were stolen by African kinsmen and sold to native slaveholders. Equiano was sold again, to white European slave traders. After changing hands a few times, Equiano was transported with other enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the English colony of Virginia.

On arrival, he was bought by Michael Pascal, a lieutenant in the Royal British Navy. Pascal decided to rename him Gustavus Vassa, a Latinized form of the name Gustav Vasa, a Swedish noble who had become Gustav I of Sweden, king in the 16th century, [citation needed]. Renaming slaves was common practice among slaveholders when they purchased them. This was but one of many names Equiano had been given by slave owners through his life. This time Equiano refused and told his new owner that he would prefer to be called Jacob. As punishment, Pascal had Equiano cuffed and told him that the shackles would remain until he accepted the new name.

Equiano wrote in his narrative that slaves working inside the slaveholders' homes in Virginia were treated cruelly. They suffered punishments such as an "iron muzzle", used around the mouths to keep house slaves quiet, and leaving them barely able to speak or eat. Equiano conveyed the fear and amazement he experienced in his new environment. He thought that the eyes of portraits followed him wherever he went, and that a clock could tell his master about anything Equiano would do wrong.

As the slave of a naval captain, Equiano received training in seamanship and traveled extensively with his master. This was during the Seven Years War with France. Although Pascal's personal servant, Equiano was also expected to fight in times of battle; his duty was to haul gunpowder to the gun decks. As one of Pascal's favourites, Equiano was sent to Ms. Guerin, Pascal's sister in England, to attend school and learn to read.

The other slaves warned Equiano that if he was not baptized, he would not be able to go to Heaven. His master allowed Equiano to be baptized in St. Margaret's Church, Westminster, in February 1759. Despite the special treatment, after the English won the war, Equiano did not receive a share of the prize money, as was awarded to the other sailors. Pascal had also promised his freedom but did not release him.

Later, Pascal sold Equiano at the island of Montserrat, in the Caribbean Leeward Islands. His literacy and seamanship skills overqualified him for plantation labour. It also made him less desirable to some slaveholders.

He was purchased by Robert King, a Quaker merchant from Philadelphia who traded in the Caribbean. King set Equiano to work on his shipping routes and in his stores. In 1765, King promised that for forty pounds, the price he had paid, Equiano could buy his freedom. King taught him to read and write more fluently, educated him in the Christian faith, and allowed Equiano to engage in profitable trading on his own as well as on his master's behalf. He enabled Equiano to earn his freedom, which he achieved by his early twenties.

King urged Equiano to stay on as a business partner, but Equiano found it dangerous and limiting to remain in the British colonies as a freed black. For instance, while loading a ship in Georgia, he was almost kidnapped back into slavery. He was released after proving his education. Equiano returned to England where, after Somersett's Case of 1772, men believed they were free of the risk of enslavement.

Pioneer of the abolitionist cause

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

After several years of trading, Equiano traveled to London and became involved in the abolitionist movement. The movement had been particularly strong amongst Quakers, but was by then non-denominational. Equiano was Methodist, having been influenced by George Whitefield's evangelism in the New World.

Equiano proved to be a popular speaker. He was introduced to many senior and influential people, who encouraged him to write and publish his life story. Equiano was supported financially by philanthropic abolitionists and religious benefactors; his lectures and preparation for the book were promoted by, among others, Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.

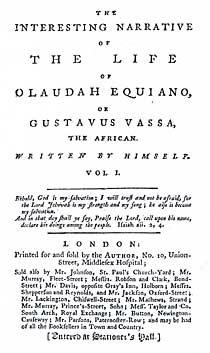

His account surprised many with the quality of its imagery, description, and literary style. Some who had not yet joined the abolitionist cause felt shame at learning of his suffering. Entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, it was first published in 1789 and rapidly went through several editions. It is one of the earliest known examples of published writing by an African writer. It was the first influential slave autobiography. Equiano's personal account of slavery and of his experiences as an 18th-century black immigrant caused a sensation when published in 1789. The book fueled a growing anti-slavery movement in England.

Equiano's narrative begins in the West African village where he was kidnapped into slavery in 1756. He vividly recalls the horror of the Middle Passage: "I now wished for the last friend, Death, to relieve me." The young Equiano was taken to a Virginia plantation where he witnessed torture. Slavery, he explained, brutalizes everyone — the slaves, their overseers, plantation wives, and the whole of society.

The autobiography goes on to describe how Equiano's adventures brought him to London, where he married into English society and became a leading abolitionist. His exposé of the infamous slave-ship Zong, whose 133 slaves were thrown overboard in mid-ocean for the owners to claim insurance money, shook the nation. Equiano's book proved his most lasting contribution to the abolitionist movement, as the book vividly demonstrated the humanity of Africans as much as the inhumanity of slavery.

The book not only was an exemplary work of English literature by a new, African author, but it made Equiano's fortune. The returns gave him independence from benefactors and enabled him to fully chart his own purpose. He worked to improve economic, social and educational conditions in Africa, particularly in Sierra Leone.

Equiano recalls his childhood in Essaka (an Igbo village formerly in southeast Nigeria), where he was adorned in the tradition of the "greatest warriors." He is unique in his account of traditional African life before the advent of the European slave trade. Equally significant is Equiano's life on the high seas, including travels throughout the Americas, Turkey and the Mediterranean. He also fought in major naval battles during the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War), and searched for a Northwest Passage, on the Phipps Expedition of 1772–73.

Equiano records his and Granville Sharp's central roles in the British Abolitionist Movement. As a major voice in this movement, Equiano petitioned the Queen of England in 1788. He was appointed to an expedition to resettle London's poor Blacks in Sierra Leone, a British colony on the west coast of Africa. He was dismissed after protesting against financial mismanagement.[4]

Conversion

Equiano's Interesting Narrative not only traces his path from enslavement to freedom, but his spiritual conversion. This conversion marks a distinctive disruption of the text. It is followed by a chapter of "Miscellaneous Verses", which relate the transformation from Equiano's enslaved "orphan state"[5] to an epiphany that his "soul and Christ were now as one---."[6] Scholars have debated the degree of Equiano's conversion. Some critics read Equiano's conversion as an adoption of Christian discourse, which inevitably leads him towards assimilation in English society. Another calls Equiano's Christianity "nominal."[7] Another claims that Equiano's Christianity is rhetorical, used to “situate himself at the heart of Englishness.”[8]

Scholars also read his account as portraying his life and conversion in terms of the Old Testament and New Testament model. This type of Christian exegesis shows how Equiano could "read his life as a progress, without closing off the paths that circle back to where he began."[9] Another critic suggests Equiano's conversion is serious, and his "search for ‘true’ religion stands as a central organizing principle of the life that he narrated, and it was in his second birth as a Christian that he believed himself to have archived true freedom.”[10] Equiano's spiritual freedom related to his desire for emancipation. This directs attention to the differences between the freedom of soul and body. Other scholars have tied an examination of Turkey and the Muslim world to analysis of Equiano's treatment of Christianity in the narrative.[11] Equiano clearly used Christian theological elements to show how they shaped him. His conversion demonstrated the paradox of enslaving fellow Christians. Further, he expressed the question of whether a black subaltern person could assimilate into a church controlled by a colonizing nation.

Family in Britain

At some point, after having travelled widely, Equiano decided to settle in Britain and raise a family. Equiano is closely associated with Soham, Cambridgeshire, where, on 7 April 1792, he married Susannah Cullen, a local girl, in St Andrew's Church. The original marriage register containing the entry for Equiano and Susannah is today held by Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies at the County Record Office in Cambridge.

He announced his wedding in every edition of his autobiography from 1792 onwards, and it has been suggested his marriage mirrored his anticipation of a commercial union between Africa and Great Britain. The couple settled in the area and had two daughters, Anna Maria, born 16 October 1793, and Joanna, born 11 April 1795.

Susannah died in February 1796 aged 34, and Equiano died a year after that on 31 March 1797, aged approximately 52. Soon after, the elder daughter died, aged four years old, leaving Joanna to inherit Equiano's estate, which was valued at £950: a considerable sum, worth approximately £100,000 today. Joanna married the Rev. Henry Bromley, and they ran a Congregational Chapel at Clavering near Saffron Walden in Essex, before moving to London in the middle of the nineteenth century. They are both buried at the Congregationalists' non-denominational Abney Park Cemetery, in Stoke Newington.

Last days and will

Although Equiano's death is recorded in London, 1797, the location of his burial is unsubstantiated. One of his last London addresses appears to have been Plaisterer's Hall in the City of London (where he drew up his will on 28 May 1796).

Having drawn up his will, Olaudah Equiano moved to John Street, Tottenham Court Road, close to Whitefield's Methodist chapel. (It was renovated for Congregationalists in the 1950s. Now the American Church in London, the church recently placed a small memorial to Equiano.) Lastly, he lived in Paddington Street, Middlesex, where he died. Equiano's death was reported in newspaper obituaries.

In the 1790s, at the time of the excesses of the French Revolution and close on the heels of the American Revolution, British society was tense because of fears of open revolution. Reformers were considered more suspect than in other periods. Equiano had been an active member of the London Corresponding Society, which campaigned to extend the vote to working men. His close friend Thomas Hardy, the Society's Secretary, was prosecuted by the government (though without success) on the basis that such political activity amounted to treason. In December 1797, apparently unaware that Equiano had died nine months earlier, a writer for the government-sponsored Anti-Jacobin, or Weekly Examiner satirised Equiano as being at a fictional meeting of the Friends of Freedom.

Equiano's will provided for projects he considered important. Had his daughter Joanna died before reaching the age of inheritance (twenty-one), half his wealth would have passed to the Sierra Leone Company for continued assistance to West Africans, and half to the London Missionary Society, which promoted education overseas. This organization had been formed the previous November at the Countess of Huntingdon's Spa Fields Chapel. By the early nineteenth century, The Missionary Society had become well known worldwide as non-denominational, though it was largely Congregational.

Modern views

Controversy of origin

Scholars have disagreed about Equiano's origins. Some believe Equiano may have fabricated his African roots and his survival of the Middle Passage not only to sell more copies of his book, but also to help advance the movement against the slave trade.

Equiano was certainly African by descent. The circumstantial evidence that Equiano was also African American by birth and African British by choice is compelling but not absolutely conclusive. Although the circumstantial evidence is not equivalent to proof, anyone dealing with Equiano's life and art must consider it.

Baptismal records and a naval muster roll appear to link Equiano to South Carolina. Records of Equiano's first voyage to the Arctic state he was from Carolina, not Africa.[13] Equiano may have been the source for information linking him to Carolina, but it may also have been a clerk's careless record of origin. Scholars continue to search for evidence to substantiate Equiano's claim of birth in Africa. Currently, no separate documentation supports this story.

For some scholars, the fact that many parts of Equiano's account can be proven lends weight to accepting his story of African birth. "In the long and fascinating history of autobiographies that distort or exaggerate the truth. ...Seldom is one crucial portion of a memoir totally fabricated and the remainder scrupulously accurate; among autobiographers... both dissemblers and truth-tellers tend to be consistent."[14]

A recent work claimed that, in a Nigerian town known as Isseke, there was local oral history that told of Equiano's upbringing.[15]. Prior to this work, however, no town bearing a name of that spelling had been recorded. Other scholars, including Nigerians, have pointed out grave errors in the research.

"Historians have never discredited the accuracy of Equiano's narrative, nor the power it had to support the abolitionist cause [...] particularly in Britain during the 1790s. However, parts of Equiano's account of the Middle Passage may have been based on already published accounts or the experiences of those he knew."[16]

Portrayal in mass media

- A BBC production in 2005 employed dramatic reconstruction, archival material and interviews with scholars such as Stuart Hall and Ian Duffield to provide the social and economic context of the 18th-century slave trade.

- Equiano was portrayed by the Senegalese singer and musician Youssou N'Dour in the 2007 film Amazing Grace.

- African Snow, a play by Murray Watts, takes place in John Newton's mind. It was first produced at the York Theatre Royal as a co-production with Riding Lights Theatre Company in April 2007 before transferring to the Trafalgar Studios in London's West End and a National Tour. Newton was played by Roger Alborough and Equiano by Israel Oyelumade.

- Stone Publishing House published a children's book entitled Equiano: The Slave with the Loud Voice. Illustrated by Cheryl Ives, it was written by Kent historian Dr. Robert Hume.

- In 2007, David and Jessica Oyelowo appeared as Olaudah and his wife in Grace Unshackled – The Olaudah Equiano Story, a radio adaptation of Equiano's autobiography. This was first broadcast on BBC 7 on Easter Sunday 8 April 2007.[17]

- The British Jazz artist Soweto Kinch first album contains a track called "Equiano's Tears".

References

- ^ (Olauda Ikwuano correct spelling of name by modern standards) http://emeagwali.com/letters/dear-professor-emeagwali-onye-igbo-ka-nbu.htm

- ^ Other biographies claim Equiano was born in colonial South Carolina, not in Africa (see: External links).

- ^ Equiano, Olaudah (2005). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African. Gutenberg Project.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Longman Anthology of British Literature, Volume 2A: The Romantics and Their Contemporaries, p. 211.

- ^ The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Ed. Shelly Eversley. New York: Modern Library, 203

- ^ The Interesting Narrative of the LIfe of Olaudah Equiano, Ed. Shelly Eversley. New York: Modern Library, 205

- ^ Marren, Susan M. "Between Slavery and Freedom: The Transgressive Self in Olaudah Equiano's Autobiography", PMLA 108 (1993): 101.

- ^ Earley, Samantha M. "Writing from the Center of the Margins? Olaudah Equiano's Writing Life Reassessed", African Studies Review, Dec. 2003: 3.

- ^ Potkay, Adam. "Olaudah Equiano and the Art of Spiritual Autobiography", Eighteenth-Century Studies 27 (1994): 692.

- ^ Sidbury, James. “From Igbo Israeli to African Christian: The Emergence of Racial Identity in Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative”, Africas of the Americas: Beyond the Search for Origins in the Study of Afro-Atlantic Religions. Ed. Stephan Palmié. Leiden: Brill, 2008, 89.

- ^ Duffield, Ian and Paul Edwards, “Equiano's Turks and Christians: An Eighteenth Century View of Islam”, Journal of African Studies, 2:4 (1975): 433-44.

- ^ Carretta,2005

- ^ "The True Story of Equiano". The Nation.

- ^ Adam Hochschild, Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves (Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 2006), 467 pp., paperback: ISBN 978-0-618-61907-8, p. 372.

- ^ Catherine Obianuju Acholonu, The Igbo Roots Of Olaudah Equiano: An Anthropological Research (1989)

- ^ "Olaudah Equiano". Soham.

- ^ "Grace Unshackled: The Olaudah Equiano Story". BBC. Sunday 15 April 2007. Retrieved 2009-1-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)

External links

- Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African Brycchan Carey's comprehensive collection of resources for the study of Equiano.

- Works by Olaudah Equiano at Project Gutenberg

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself. Vol. I. London: Author, [1789].

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself. Vol. II. London: Author, [1789].

- Audio recording of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano at LibriVox

- Olaudah Equiano at the BBC

- Africans in America - Olaudah Equiano at PBS

- Equiano at Parliament and the British Slave Trade 1600-1807

- Olaudah Equiano: Black Britain's Political Founding Father at 100 Great Black Britons

- The Equiano Project The Equiano Society and Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

- Remembering Equiano - Soham at the Time of the Abolition Soham Community History Museum & Soham Action 4 Youth

Dramatic recreations

- Let Justice Be Done Mixed Blessings Theatre Group. 2008 play with Equiano playing a possible part in a meeting with the Earl of Mansfield in the late 1770s

- African Snow Riding Lights Theatre Company. 2007 play featuring Equiano's story

- Amazing Grace official US website

- Amazing Grace official UK website

- A Son of Africa 1998 short film distributed by California Newsreel

Birthplace dispute

- Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African Paul E. Lovejoy. May-October 2005.

- "Where Was Olaudah Equiano Born?" [1] Brycchan Carey's list of Africanist/Americanist positions. (accessed 11 June 2007)

- Unraveling the Narrative Jennifer Howard. The Chronicle of Higher Education, September 9, 2005.

- Olaudah Equiano: A Critical Biography Brycchan Carey. 13 December 2005.