Griffin

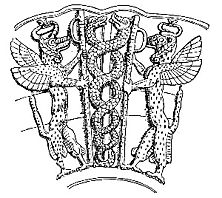

The griffin (griffon or gryphon (see below)) is a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. As the lion was traditionally considered the king of the beasts and the eagle was the king of the birds, the griffin was thought to be an especially powerful and majestic creature. Griffins are normally known for guarding treasure.[1] In antiquity it was a symbol of divine power and a guardian of the divine.[2]

Most contemporary illustrations give the griffin legs like an eagle's legs with talons, although in some older illustrations it has a lion's forelimbs; it generally has a lion's hindquarters. Its eagle's head is conventionally given prominent ears; these are sometimes described as the lion's ears, but are often elongated (more like a horse's), and are sometimes feathered.

Infrequently, a griffin is portrayed without wings (or a wingless eagle-headed lion is identified as a griffin); in 15th-century and later heraldry such a beast may be called an alce or a keythong. In heraldry, a griffin always has forelegs like an eagle's; the beast with forelimbs like a lion's forelegs was distinguished by perhaps only one English herald of later heraldry as the opinicus. The modern generalist calls it the lion-griffin, as for example, Robin Lane Fox, in Alexander the Great, 1973:31 and notes p. 506, who remarks a lion-griffin attacking a stag in a pebble mosaic at Pella, perhaps as an emblem of the kingdom of Macedon or a personal one of Alexander's successor Antipater.

Spelling and etymology

According to the Oxford English Dictionary: "the regular modern spelling [for heraldry and surgery related] is griffon, in other senses usually griffin, though gryphon is used by many writers as having more dignified associations."[3]

Although, the spelling "griffon" (from Middle English and Middle French) might be disproportionately common due to overlapping use with the griffon dog breed. Less common variants include gryphen, griffen, and gryphin; from Latin grȳphus, from Greek γρύψ gryps, from γρύπος grypos hooked.

Possible origins of griffin stories

Scholar Adrienne Mayor argues that the griffin was inspired by protoceratops fossils in Central Asia.[4] Mayor noted that, like griffins, protoceratops had beaked faces, protected eggs in nests, and were associated with gold due to their fossils often being located in or near gold-bearing ores.

From Achaemenid Persian Empire to Central Asia

The griffin appeared at least as early as the 5th-4th century BC in Central Asia, probably originating from the Achaemenid Persian Empire. There and then, the griffin was a protector from evil.[5]

Medieval lore

A 9th-century Irish writer by the name of Stephen Scotus [citation needed] asserted that griffins were strictly monogamous. Not only did they mate for life, but if one partner died, the other would continue throughout the rest of its life alone, never to search for a new mate. The griffin was thus made an emblem of the Church's views on remarriage.

Being a union of a terrestrial beast and an aerial bird, it was seen in Christianity to be a symbol of Jesus, who was both human and divine. As such it can be found sculpted on churches.[1]

According to Stephen Friar, a griffin's claw was believed to have medicinal properties and one of its feathers could restore sight to the blind.[1] Goblets fashioned from griffin claws (actually antelope horns) and griffin eggs (actually ostrich eggs) were highly prized in medieval European courts.[6]

Since its emergence as a major seafaring power in the Middle Ages and Renaissance griffins have been depicted as part of the Republic of Genoa's coat of arms, rearing at the sides of the shield bearing the Cross of St. George.

By the 12th century the appearance of the griffin was substantially fixed: "All its bodily members are like a lion's, but its wings and mask are like an eagle's."[7] It is not yet clear if its forelimbs are those of an eagle or of a lion. Although the description implies the latter, the accompanying illustration is ambiguous. It was left to the heralds to clarify that.

Heraldic significance

In heraldry, the griffin's amalgamation of lion and eagle gains in courage and boldness, and it is always drawn as a powerful fierce monster. It is used to denote strength and military courage and leadership. Griffins are portrayed with a lion's body, an eagle's head, long ears, and an eagle's claws, to indicate that one must combine intelligence and strength.[8]

In British heraldry a male griffin is shown with wings, its body covered in tufts of formidable spikes. The male griffin is more usually shown, as in the Bevan family crest (illustration).[9]

The griffin is the mascot of Rocky Mount High School located in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. During the era of segregation, Rocky Mount High School was an all-white school while African Americans attended Booker T. Washington High School. In 1969, the two schools merged when segregation ended. During that time, the mascot of Rocky Mount High School was the blackbird and the lion was the mascot of Booker T. Washington. In an attempt to create a new mascot for the newly merged school and at the same time maintaining the history of the two schools, the griffin (or gryphon as it is spelled) became the obvious choice.

The gryphon is part of the coat of arms of Raffles Institution, the oldest school in Singapore. Combined with the strength of the double-headed eagle, it represents power, strength, supremacy, dignity and majesty for the school[10].

In architecture

In architectural decoration the griffin is usually represented as a four-footed beast with wings and the head of a leopard or tiger with horns, or with the head and beak of an eagle.[citation needed]

The griffin is the symbol of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; bronze castings of them perched on each corner of the museum's roof, protecting its collection.[11][12]

The griffin is the mascot of Missouri Western State University in Saint Joseph, Missouri. It was chosen in 1918 as the mascot of Saint Joseph Junior College, the institution which later became Missouri Western State University. The griffin was selected because it was considered a guardian of riches, and education is viewed as a precious treasure.

Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts uses four animals and colors to represent the four class years. One of these is the green griffin, representing one of the odd graduating years. It was selected as one of the four class animals in 1909.[13]

Gryphon statues mark the entrance to the City of London.

In literature

- For fictional characters named Griffin, see Griffin (surname)

- John Milton, in Book II of Paradise Lost, refers to the legend of the griffin in describing Satan:

As when a Gryfon through the Wilderness

With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale,

Pursues the ARIMASPIAN, who by stelth

Had from his wakeful custody purloind

The guarded Gold [...]

- Griffins are used widely in Persian poetry. Rumi is one such poet who writes in reference to griffins (for example, in The Essential Rumi, translated from Persian by Coleman Barks, p 257).

In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Beatrice meets Dante in Earthly Paradise after his journey through Hell and Purgatory with Virgil have concluded. Beatrice takes off into the Heavens to begin Dante's journey through paradise on a flying Griffin that moves as fast as lightning. The griffin itself represents the dual nature of Christ's humanity and divinity due to the fact that the being is a mystical hybrid in mythology.

In natural history

Some large species of Old World vultures are called gryphons or stupids, including the Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus), as are some breeds of dog (griffons).

The scientific species name for the Andean Condor is Vultur gryphus; Latin for "griffin-vulture".

The name of an oviraptoran dinosaur Hagryphus giganteus is Latin for "gigantic Ha's Griffin".

As a first name and surname

In the mid-1990s, "Griffin" steadily became more popular as a baby name for boys in the U.S. In 1990, it was ranked 629th. In 2006, it was ranked 254th. Also rising in popularity is the various other spellings of the name such as Griffen or Gryphon.

"Griffin" occurs as a surname in English-speaking countries. Variations of the surname "Griffin" are present throughout most of Europe and even parts of Western Asia. It has its origins as an anglicised form of the Irish "Ó Gríobhtha", "O' Griffin", and "Ó Griffey".

Welsh people who were anglicised, changed the name to "Griffith" and similar names. This shift is reinforced where the family has taken canting arms charged with a griffin.

"Griffin" (and variants in other languages) may also have been adopted as a surname by other families who used arms charged with a griffin or a griffin's head (just as the House of Plantagenet took its name from the badge of a sprig of broom or planta genista). This is ostensibly the origin of the Swedish surname "Grip" (see main article).

Notes and references

- ^ a b c Friar, Stephen (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A & C Black. p. 173. ISBN 0906670446.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole: New Orchard Editions. pp. 44–45. ISBN 185079037X.

- ^ http://dictionary.oed.com.ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/cgi/entry/50098772?single=1&query_type=word&queryword=gryphon&first=1&max_to_show=10

- ^ http://www.gi.alaska.edu/ScienceForum/ASF12/1217.html

- ^ Central Asian Jewelry and their Symbols in Ancient Time Dr. Elena Neva

- ^ Bedingfeld, Henry (1993). Heraldry. Wigston: Magna Books. pp. 80–81. ISBN 1854224336.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ White, T. H. (1992 (1954)). The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation From a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. 22–24. ISBN 075090206X.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Stefan Oliver. Introduction to Heraldry (David & Charles) 2002. p.44.

- ^ For a recent use of a griffin in heraldry see the Baty Griffin and millstone

- ^ Raffles Institution handbook

- ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art - Giving : Giving to the Museum : Specialty License Plates

- ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art :: Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States :: Glass Steel and Stone

- ^ Mount Holyoke College - Traditions: Class Colors and Symbols

Further reading

- Bisi, Anna Maria, Il grifone: Storia di un motivo iconografico nell'antico Oriente mediterraneo (Rome: Università) 1965.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- The Gryphon Pages, a repository of griffin lore and information

- The Medieval Bestiary: Griffin

- Dave's Mythical Creatures and Places: Griffin