ZX Spectrum

| |

| Type | 8-bit Home computer |

|---|---|

| Release date | 23 April 1982 |

| Discontinued | 1992[1] |

| Operating system | Sinclair BASIC |

| CPU | Z80 @ 3.5 MHz and equivalent |

| Memory | 16 KB / 48 KB / 128 KB |

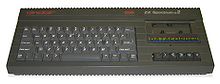

The ZX Spectrum (Pronounced: "Zed Ecks Spec-trum" in its original British English branding) is an 8-bit personal home computer released in the United Kingdom in 1982 by Sinclair Research Ltd. Referred to during development as the ZX81 Colour and ZX82,[2][3] the machine was launched as the ZX Spectrum by Sinclair to highlight the machine's colour display, compared with the black-and-white of its predecessor, the Sinclair ZX81.[4] The Spectrum was released in eight different models, ranging from the entry level model with 16 KB RAM released in 1982 to the ZX Spectrum +3 with 128 KB RAM and built in floppy disk drive in 1987.

The Spectrum was among the first mainstream audience home computers in the UK, similar in significance to the Commodore 64 in the USA. The introduction of the ZX Spectrum led to a boom in companies producing software and hardware for the machine,[5] the effects of which are still seen;[1] some credit it as the machine which launched the UK IT industry.[6] Licensing deals and clones followed, and earned Clive Sinclair a knighthood for "services to British industry".[7]

The Commodore 64 was a major rival to the Spectrum in the UK market during the early 1980s. The BBC Microcomputer and later the Amstrad CPC range were other major competitors. The ZX Spectrum has incurred a resurgence in popularity thanks to the accessibility of ZX Spectrum emulators, allowing 1980s video game enthusiasts to enjoy classic titles without the long loading times associated with data cassettes. Over 20,000 titles have been released since the Spectrum's launch, with over 60 new ones in 2009.

Hardware

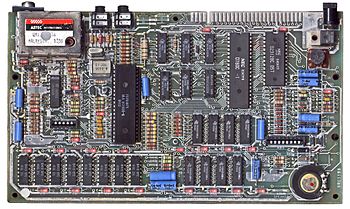

The Spectrum is based on a Zilog Z80A CPU running at 3.5 MHz (or NEC D780C-1 clone). The original model Spectrum has 16 KB (16×1024 bytes) of ROM and either 16 KB or 48 KB of RAM. Hardware design was by Richard Altwasser of Sinclair Research, and the machine's outward appearance was designed by Sinclair's industrial designer Rick Dickinson.[5]

Video output is through an RF modulator and was designed for use with contemporary portable television sets, for a simple colour graphic display. Text can be displayed using 32 columns × 24 rows of characters from the ZX Spectrum character set or from a set provided within an application, from a palette of 15 shades: seven colours at two levels of brightness each, plus black.[8] The image resolution is 256×192 with the same colour limitations.[9] To conserve memory, colour is stored separate from the pixel bitmap in a low resolution, 32×24 grid overlay, corresponding to the character cells. Altwasser received a patent for this design.[10]

An "attribute" consists of a foreground and a background colour, a brightness level (normal or bright) and a flashing "flag" which, when set, causes the two colours to swap at regular intervals.[9] Unfortunately, this scheme leads to what was dubbed colour clash or attribute clash with some bizarre effects in the animated graphics of arcade style games. This problem became a distinctive feature of the Spectrum and an in-joke among Spectrum users, as well as a point of derision by advocates of other systems. Other machines available around the same time, for example the Amstrad CPC, did not suffer from this limitation. The Commodore 64 used colour attributes in a similar way, but a special multicolour mode, hardware sprites and scrolling were used to avoid attribute clash.

Sound output is through a beeper on the machine itself. This is capable of producing one channel with 10 octaves. The machine also includes an expansion bus edge connector and audio in/out ports for the connection of a cassette recorder for loading and saving programs and data.

The machine's Sinclair BASIC interpreter is stored in ROM (along with fundamental system-routines) and was written by Steve Vickers on contract from Nine Tiles Ltd. The Spectrum's chiclet keyboard (on top of a membrane, similar to calculator keys) is marked with BASIC keywords, so that, for example, pressing "G" when in programming mode would insert the BASIC command GO TO.[11]

Models

Pre-production designs

Rick Dickinson came up with a number of designs called the ZX82 before the finalised ZX Spectrum. A number of the keyboard legends changed during the design phase including ARC becoming CIRCLE, FORE becoming INK and BACK becoming PAPER.

Sinclair Research models

ZX Spectrum 16K/48K

The original ZX Spectrum is remembered for its rubber keyboard, diminutive size and distinctive rainbow motif. It was originally released in 1982 with 16 KB of RAM for £125 Sterling or with 48 KB for £175;[13] these prices were later reduced to £99 and £129 respectively.[14] Owners of the 16 KB model could purchase an internal 32 KB RAM upgrade, which for early "Issue 1" machines consisted of a daughterboard. Later issue machines required the fitting of 8 dynamic RAM chips and a few TTL chips. Users could mail their 16K Spectrums to Sinclair to be upgraded to 48 KB versions. To reduce the price, the 32 KB extension used eight faulty 64 kilobit chips with only one half of their capacity working and/or available.[15] External 32 KB RAM packs that mounted in the rear expansion slot were also available from third parties. Both machines had 16 KB of onboard ROM.

About 60,000 "Issue 1" ZX Spectrums were manufactured; they can be distinguished from later models by the colour of the keys (light grey for Issue 1, blue-grey for later models).[16]

ZX Spectrum+

Planning of the ZX Spectrum+ started in June 1984,[17] and the machine was released in October the same year.[18] This 48 KB Spectrum (development code-name TB[17]) introduced a new QL-style case with an injection-moulded keyboard and a reset button. Electronically, it was identical to the previous 48 KB model. It retailed for £179.95.[19] A DIY conversion-kit for older machines was also available. Early on, the machine outsold the rubber-key model 2:1;[17] however, some retailers reported a failure rate of up to 30%, compared with a more usual 5-6%.[18]

ZX Spectrum 128

Sinclair developed the ZX Spectrum 128 (code-named Derby) in conjunction with their Spanish distributor Investrónica.[20] Investrónica had helped adapt the ZX Spectrum+ to the Spanish market after the Spanish government introduced a special tax on all computers with 64 KB RAM or less which did not support the Spanish alphabet (such as ñ) and show messages in Spanish.[21]

New features included 128 KB RAM, three-channel audio via the AY-3-8912 chip, MIDI compatibility, an RS-232 serial port, an RGB monitor port, 32 KB of ROM including an improved BASIC editor, and an external keypad.

The machine was simultaneously presented for the first time and launched in September 1985 at the SIMO '85 trade show in Spain, with a price of 44,250 pesetas. Because of the large amount of unsold Spectrum+ models, Sinclair decided not to start selling in the UK until January 1986 at a price of £179.95.[22] No external keypad was available for the UK release, although the ROM routines to use it and the port itself, which was hastily renamed "AUX", remained.

The Z80 processor used in the Spectrum has a 16-bit address bus, which means only 64 KB of memory can be directly addressed. To facilitate the extra 80 KB of RAM the designers used bank switching so that the new memory would be available as eight pages of 16 KB at the top of the address space. The same technique was also used to page between the new 16 KB editor ROM and the original 16 KB BASIC ROM at the bottom of the address space.

The new sound chip and MIDI out abilities were exposed to the BASIC programming language with the command PLAY and a new command SPECTRUM was added to switch the machine into 48K mode, keeping the current BASIC program intact (although there is no way to switch back to 128K mode). To enable BASIC programmers to access the additional memory, a RAM disk was created where files could be stored in the additional 80 KB of RAM. The new commands took the place of two existing user-defined-character spaces causing compatibility problems with some BASIC programs.

The Spanish version had the "128K" logo (right, bottom of the computer) in white while the English one had the same logo in red.

Amstrad models

ZX Spectrum +2

The ZX Spectrum +2 was Amstrad's first Spectrum, coming shortly after their purchase of the Spectrum range and "Sinclair" brand in 1986. The machine featured an all-new grey case featuring a spring-loaded keyboard, dual joystick ports, and a built-in cassette recorder dubbed the "Datacorder" (like the Amstrad CPC 464), but was in most respects identical to the ZX Spectrum 128. The main menu screen lacked the Spectrum 128's "Tape Test" option, and the ROM was altered to account for a new 1986 Amstrad copyright message. These changes resulted in minor incompatibility problems with software that accessed ROM routines at certain addresses. Production costs had been reduced and the retail price dropped to £139–£149.[23]

The new keyboard did not include the BASIC keyword markings that were found on earlier Spectrums, except for the keywords LOAD, CODE and RUN which were useful for loading software. This was not a major issue however, as the +2 boasted a menu system, almost identical to the ZX Spectrum 128, where one could switch between 48k BASIC programming with the keywords, and 128k BASIC programming in which all words (keywords and otherwise) must be typed out in full (although the keywords are still stored internally as one character each). Despite these changes, the layout remained identical to that of the 128.

ZX Spectrum +2A

The ZX Spectrum +2A was produced to homogenise Amstrad's range in 1987. Although the case reads "ZX Spectrum +2", the +2A/B is easily distinguishable from the original +2 as the case was restored to the standard Spectrum black.

The +2A was derived from Amstrad's +3 4.1 ROM model, using a new motherboard which vastly reduced the chip count, integrating many of them into a new ASIC. The +2A replaced the +3's disk drive and associated hardware with a tape drive, as in the original +2. Originally, Amstrad planned to introduce an additional disk interface, but this never appeared. If an external disk drive was added, the "+2A" on the system OS menu would change to a +3. As with the ZX Spectrum +3, some older 48K, and a few older 128K, games were incompatible with the machine.

ZX Spectrum +2B

The ZX Spectrum +2B signified a manufacturing move from Hong Kong to Taiwan later in 1987.[24]

ZX Spectrum +3

The ZX Spectrum +3 looked similar to the +2 but featured a built-in 3-inch floppy disk drive (like the Amstrad CPC 6128) instead of the tape drive, and was in a black case. It was launched in 1987, initially retailed for £249[25] and then later £199[26] and was the only Spectrum capable of running the CP/M operating system without additional hardware.

The +3 saw the addition of two more 16 KB ROMs. One was home to the second part of the reorganised 128 ROM and the other hosted the +3's disk operating system. This was a modified version of Amstrad's AMSDOS, called +3DOS. These two new 16 KB ROMs and the original two 16 KB ROMs were now physically implemented together as two 32 KB chips. To be able to run CP/M, which requires RAM at the bottom of the address space, the bank-switching was further improved, allowing the ROM to be paged out for another 16 KB of RAM.

Such core changes brought incompatibilities:

- Removal of several lines on the expansion bus edge connector (video, power, and IORQGE); caused many external devices problems; some such as the VTX5000 modem could be used via the "FixIt" device

- Dividing ROMCS into 2 lines, to disable both ROMs

- Reading a non-existent I/O port no longer returned the last attribute; caused some games such as Arkanoid to be unplayable

- Memory timing changes; some of the RAM banks were now contended causing high-speed colour-changing effects to fail

- The keypad scanning routines from the ROM were removed

- move 1 byte address in ROM

Some older 48K, and a few older 128K, games were incompatible with the machine.

The +3 was the final official model of the Spectrum to be manufactured, remaining in production until December 1990. Although still accounting for one third of all home computer sales in the UK at the time, production of the model was ceased by Amstrad at that point.

Clones

Sinclair licensed the Spectrum design to Timex Corporation in the United States. An enhanced version of the Spectrum with better sound, graphics and other modifications was marketed in the USA by Timex as the Timex Sinclair 2068. Timex's derivatives were largely incompatible with Sinclair systems. However, some of the Timex innovations were later adopted by Sinclair Research. A case in point was the abortive Pandora portable Spectrum, whose ULA had the high resolution video mode pioneered in the TS2068. Pandora had a flat-screen monitor and Microdrives and was intended to be Sinclair's business portable. When Alan Sugar bought the computer side of Sinclair it got ditched (a conversation with UK computer journalist Guy Kewney went thus: AS: "Have you seen it?" GK: "Yes" AS: "Well then.").[27]

In the UK, Spectrum peripheral vendor Miles Gordon Technology (MGT) released the SAM Coupé as a potential successor with some Spectrum compatibility. However, by this point, the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST had taken hold of the market, leaving MGT in eventual receivership.

Many unofficial Spectrum clones were produced, especially in the former Eastern Bloc countries (e.g. in Romania, several models were produced (Tim-S, HC85, HC91, Cobra, Junior, CIP, CIP 3, Jet) , some featuring CP/M and a 5.25"/3.5" floppy disk) and South America (e.g. Microdigital TK 90X and TK 95). In Russia / Soviet Union, ZX Spectrum clones were assembled by thousands of small start-ups and distributed though poster ads and street stalls. Over 50 such clone models existed.[28] Some of them are still being produced, such as the Pentagon and ATM Turbo. In India, Decibells Electronics introduced a licensed version of the Spectrum+ in 1986. Dubbed the "db Spectrum+", it did reasonably well in the Indian market and sold quite a few thousand until 1990 when the market died away.

Peripherals

Several peripherals for the Spectrum were marketed by Sinclair: the ZX Printer was already on the market,[29] as the ZX Spectrum expansion bus was backwards-compatible with that of the ZX81.

The ZX Interface 1 add-on module included 8 KB of ROM, an RS-232 serial port, a proprietary LAN interface (called ZX Net), and an interface for the connection of up to eight ZX Microdrives – somewhat unreliable but speedy tape-loop cartridge storage devices released in July 1983.[30][31] These were later used in a revised version on the Sinclair QL, whose storage format was electrically compatible but logically incompatible with the Spectrum's. Sinclair also released the ZX Interface 2 which added two joystick ports and a ROM cartridge port.[32]

There were also a plethora of third-party hardware addons. The better known of these included the Kempston joystick interface, the Morex Peripherals Centronics/RS-232 interface, the Currah Microspeech unit (speech synthesis),[33] Videoface Digitiser,[34] RAM pack, the Cheetah Marketing SpecDrum,[35] a drum machine, and the Multiface,[36] a snapshot and disassembly tool from Romantic Robot. Keyboards were especially popular in view of the original's notorious "dead flesh" feel.[37]

There were numerous disk drive interfaces, including the Abbeydale Designers/Watford Electronics SPDOS, Abbeydale Designers/Kempston KDOS and Opus Discovery. The SPDOS and KDOS interfaces were the first to come bundled with Office productivity software (Tasword Word Processor, Masterfile database and OmniCalc spreadsheet). This bundle, together with OCP's Stock Control, Finance and Payroll systems, introduced many small businesses to a streamlined, computerised operation. The most popular floppy disk systems (except in East Europe) were the DISCiPLE and +D systems released by Miles Gordon Technology in 1987 and 1988 respectively. Both systems had the ability to store memory images onto disk snapshots could later be used to restore the Spectrum to its exact previous state. They were also both compatible with the Microdrive command syntax, which made porting existing software much simpler.[38]

During the mid-1980s, the company Micronet800 launched a service allowing users to connect their ZX Spectrums via a Prism Micro Products modem to a bulletin board system known as Micronet hosted by Prestel. This service had some similarities to the Internet, but was proprietary and fee-based.

Software

The Spectrum enjoys a vibrant, dedicated fan-base.[39][40] Since it was cheap and simple to learn to use and program, the Spectrum was the starting point for many programmers.[1] The hardware limitations of the Spectrum imposed a special level of creativity on game designers, and so many Spectrum games are very creative and playable even by today's standards.[41] The early Spectrum models' great success as a games platform came in spite of its lack of built-in joystick ports, primitive sound generation, and colour support that was optimised for text display.[42]

The Spectrum family enjoys a very large software library of more than 20,000 titles.[43] While most of these were games, the library was very diverse, including programming language implementations, databases (eg VU-File[44]), word processors (eg Tasword II[45]), spreadsheets (eg VU-Calc[44]), drawing and painting tools (eg OCP Art Studio[46]), and even 3D-modelling (e.g. VU-3D[47][48]) as well as astronomy and astrology programs[49] and archaeology software.[50]

Distribution

Most Spectrum software was originally distributed on audio cassette tapes. The Spectrum was intended to work with a normal domestic cassette recorder,[51] and despite differences in audio reproduction fidelity, the software loading process was quite reliable, if somewhat slow (by today's standards).

Although the ZX Microdrive was initially greeted with good reviews,[52] it never took off as a distribution method due to worries about the quality of the cartridges and piracy.[53] Hence the main use became to complement tape releases, usually utilities and niche products like the Tasword word processing software and Trans Express, (a tape to microdrive copying utility). No games are known to be exclusively released on Microdrive.

Despite the popularity of the DISCiPLE and +D systems, most software released for them took the form of utility software. The ZX Spectrum +3 enjoyed much more success when it came to commercial software releases on floppy disk. More than 700 titles were released on 3-inch disk from 1987 to 1997.[43]

Software was also distributed through print media; magazines[54] and books.[55] The reader would type the Sinclair BASIC program listing into the computer by hand, run it, and could save it to tape for later use. The software distributed in this way was in general simpler and slower than its assembly language counterparts. But soon, magazines were printing long lists of checksummed hexadecimal digits with machine code games or tools.

Another software distribution method was to broadcast the audio stream from the cassette on another medium and have users record it onto an audio cassette themselves. In radio or television shows in many European countries, the host would describe a program, instruct the audience to connect a cassette tape recorder to the radio or TV and then broadcast the program over the airwaves in audio format.[56] Some magazines distributed 7" 33⅓ rpm flexidisc records, a variant of regular vinyl records which could be played on a standard record player.[57] These disks were known as floppy ROMs.

Copying and backup software

Many "copiers", utilities to copy programs from audio tape to another tape, microdrive tapes, and later on diskettes, were available for the Spectrum.[58] As a response to this, publishers introduced copy protection measures to their software, including different loading schemes.[59] Other methods for copy prevention were also used including asking for a particular word from the documentation included with the game – often a novella like in Silicon Dreams trilogy – or another physical device distributed with the software – e.g. Lenslok as used in Elite. Special hardware, such as Romantic Robot's Multiface, was able to dump a copy of the ZX Spectrum RAM to disk/tape at the press of a button, entirely circumventing the copy protection systems.

Most Spectrum software has been digitised in recent years and is available for download in digital form. One popular program for digitising Spectrum software is Taper: it allows connecting a cassette tape player to the line in port of a sound card or, through a simple home-built device, to the parallel port of a PC.[60] Once in digital form, the software can be executed on one of many existing emulators, on virtually any platform available today. Today, the largest on-line archive of ZX Spectrum software is World of Spectrum, with more than 18,000 titles. The legality of this practice is still in question and a number of authors have explicitly objected to the posting of their software, with which some Spectrum abandonware sites have usually complied.[61]

Notable developers

A number of current leading games developers and development companies began their careers on the ZX Spectrum, including David Perry of Shiny Entertainment, and Tim and Chris Stamper (founders of Ultimate Play The Game, now known as Rare, maker of many famous titles for Nintendo and Microsoft game consoles). Other prominent games developers include Julian Gollop (Chaos, Rebelstar, X-COM series), Matthew Smith (Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy), Jon Ritman (Match Day, Head Over Heels), The Oliver Twins (the Dizzy series), Clive Townsend (Saboteur) and Alan Cox.[62]

Jeff Minter ported some of his Commodore VIC-20 games for the ZX Spectrum.[63]

Community

The ZX Spectrum enjoyed a very strong community early on. Several dedicated magazines were released including Sinclair User (1982), Your Sinclair (1983) and CRASH (1984). Early on they were very technically oriented with type-in programs and machine code tutorials. Later on they became almost completely game-oriented. Several general contemporary computer magazines covered the ZX Spectrum in more or less detail. They included Computer Gamer, Computer and Video Games, Computing Today, Popular Computing Weekly, Your Computer and The Games Machine.[64]

The Spectrum is affectionately known as the Speccy by elements of its fan following.[65]

More than 80 electronic magazines existed, mostly in Russian. Most notable of them were AlchNews (UK), ZX-Format (Russia), and Spectrofon (Russia).

See also

- History of computing hardware (1960s-present)

- ZX Spectrum graphic modes

- List of ZX Spectrum games

- List of ZX Spectrum clones

References

- ^ a b c "How the Spectrum began a revolution". BBC. 2007-04-23. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Dickinson, Rick. "specLOGO02". Sinclair Spectrum development. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Dickinson, Rick. "specModel01". Sinclair Spectrum development. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Klooster, Erik. "SINCLAIR ZX SPECTRUM : the good, old 'speccy'". Computer Museum. Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- ^ a b Owen, Chris. "ZX Spectrum 16K/48K". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ Williams, Chris (2007-04-23). "Sinclair ZX Spectrum: 25 today". Situation Publishing. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Text "Register Hardware" ignored (help) - ^ Owen, Chris. "ZX Spectrum". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ Vickers, Steven (1982). "Introduction". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Vickers, Steven (1982). "Colours". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ EP patent 0107687, Richard Francis Altwasser, "Display for a computer", issued 1988-07-06, assigned to Sinclair Research Ltd

- ^ Vickers, Steven (1982). "Basic programming concepts". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "The Machines". The Home Computers Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "The High Street Spectrum". ZX Computing: 43. 1983. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "News: Spectrum prices are slashed". Sinclair User (15): 13. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Goodwin, Simon (1984). "Suddenly, it's the 64K Spectrum!". Your Spectrum (7): 33–34. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Owen, Chris. "Spectrum 48K Versions". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ^ a b c Denham, Sue (1984). "The Secret That Was Spectrum+". Your Spectrum (10): 104. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Owen, Chris. "ZX Spectrum+". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "News: New Spectrum launch". Sinclair User (33): 11. 1984. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bourne, Chris (1985). "News: Launch of the Spectrum 128 in Spain". Sinclair User (44): 5. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Crookes, David. "Why QWERTY?". Micro Mart. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ "Clive discovers games — at last". Sinclair User (49): 53. 1985. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Phillips, Max (1986). "ZX Spectrum +2". Your Sinclair (11): 47. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kendall, Philip (2000-01-06). "Sinclair ZX Spectrum FAQ: Question 14". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ South, Phil (1987). "It's here... the Spectrum +3". Your Sinclair (17): 22–23. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Amstrad (1987). "The new Sinclair has one big disk advantage". Sinclair User (68): 2–3. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rupert Goodwins (2002-05-12). "Sinclair Loki Superspectrum". Newsgroup: comp.sys.sinclair. 3cde626f.45085128@news-text.blueyonder.co.uk. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- ^ Owen, Chris. "Clones and variants". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ^ Owen, Chris. "ZX Printer". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ "News: Some surprises in the Microdrive". Sinclair User (18): 15. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Adams, Stephen (1983). "Hardware World: Spectrum receives its biggest improvement". Sinclair User (19): 27–29. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hardware World: Sinclair cartridges may be out of step". Sinclair User (21): 35. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hardware World: Clear speech from Currah module". Sinclair User (21): 40. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Frey, Franco (1987). "Tech Niche: Videoface to Face". CRASH (37): 86–87. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bates, Jon (1986). "Tech Niche: SpecDrum". CRASH (27): 100. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Frey, Franco (1986). "Tech Niche: Multifaceted device". CRASH (36): 86. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hardware World: Emperor Looks Good". Sinclair User (31): 31. 1984. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Frey, Franco (1987). "Tech Niche: Pure Gospel". CRASH (38): 82–83. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "What's new". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ^ "raww.org :: zx spectrum demoscene news". Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ^ McCandless, David (1998-09-17), "Retrospectrum", Daily Telegraph

- ^ Adamson, Ian (1986-10-30). Sinclair and the "Sunrise" Technology: The Deconstruction of a Myth. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0140087745.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Heide, Martijn van der. "Archive!". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ^ a b Pearce, Nick (1982). "Zap! Pow! Boom!". ZX Computing: 75. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wetherill, Steven (1984). "Tasword Two: The Word Processor". CRASH! (5): 126. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gilbert, John (1985). "Art Studio". Sinclair User (43): 28. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Carter, Alasdair (1983). "VU-3D". ZX Computing: 76–77. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Psion Vu-3D". Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "World of Spectrum". Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Brown, Paul N. "Pitcalc — simple interactive coordinate & trigonometric calculation software". Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Vickers, Steven (1982). "6. Using the cassette recorder". Sinclair ZX Spectrum: Introduction. Sinclair Research Ltd. p. 21. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Frey, Franco (1984). "Epicventuring and Multiplayer Networking". CRASH (4): 46–47. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Foot, Cathy (1985). "Microdrive revisited". CRASH (22): 8. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Grimwood, Jim. "The Type Fantastic". Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Books". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ^ "News". Sinclair User (16): 17. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Collins, Paul Equinox. "Spectrum references in popular music". Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Inforseek". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Barker, Andy. "ZX Spectrum Loading Schemes". Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Taper". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "World of Spectrum — Software — Copyrights and Distribution Permissions". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ^ Bezroukov, Nikolai. "Alan Cox: and the Art of Making Beta Code Work". Portraits of Open Source Pioneers. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ^ Minter, Jeff. "Llamasoft History — Part 8 - The Dawn of Llamasoft". Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ "The Top Shelf — magazines, comics and papers of the near past". TV Cream's Top Shelf. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ "The YS Top 100 Speccy Games Of All Time (Ever!)". Your Sinclair (70): 31. 1991. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- World of Spectrum — Fan site officially endorsed by Amstrad

- Planet Sinclair — Spectrum pages

- Template:Dmoz

- ZXF magazine

- The Incomplete Spectrum ROM Assembly and actual assembly listing

- comp.sys.sinclair Newsgroup covering all Sinclair computers

- Sinclair Spectrum development – more preproduction designs of the Spectrum from Rick Dickinson

- The Anatomy/Dissection of a Spectrum +2B Photographic study of a +2B vs the screwdriver