Ficus

| Fig trees | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sycamore Fig, Ficus sycomorus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Tribe: | Ficeae[1] |

| Genus: | Ficus |

| Species | |

|

About 800, see text | |

Ficus (Template:Pron-en)[2] is a genus of about 850 species of woody trees, shrubs, vines, epiphytes, and hemiepiphyte in the family Moraceae. Collectively known as fig trees or figs, they are native throughout the tropics with a few species extending into the semi-warm temperate zone. The so-called Common Fig (F. carica) is a temperate species from the Middle East and eastern Europe (mostly Ukraine), which has been widely cultivated from ancient times for its fruit, also referred to as figs. The fruit of most other species are also edible though they are usually of only local economic importance or eaten as bushfood. However, they are extremely important food resources for wildlife. Figs are also of paramount cultural importance throughout the tropics, both as objects of worship and for their many practical uses.

Description

Ficus is a pan-tropical genus of trees, shrubs and vines occupying a wide variety of ecological niches; most are evergreen, but some deciduous species are endemic to areas outside of the tropics and to higher elevations.[3] Fig species are characterized by their unique inflorescence and distinctive pollination syndrome, which utilizes wasp species belonging to the Agaonidae family for pollination.

The specific identification of many of the species can be difficult, but figs as a group are relatively easy to recognize. Many have aerial roots and a distinctive shape or habit, and their fruits distinguish them from other plants. The fig fruit is an enclosed inflorescence, sometimes referred to as a syconium, an urn-like structure lined on the inside with the fig's tiny flowers. The unique fig pollination system, involving tiny, highly specific wasps, know as fig wasps that enter these closed inflorescences to both pollinate and lay their own eggs, has been a constant source of inspiration and wonder to biologists[4]. Finally, there are three vegetative traits that together are unique to figs. All figs possess a white to yellowish sap (latex), some in copious quantities; the twig has paired stipules or a circular stipule scar if the stipules have fallen off; and the lateral veins at the base of the leaf are steep, forming a tighter angle with the midrib than the other lateral veins, a feature referred to as a "tri-veined".

Unfortunately, there are no unambiguous older fossils of Ficus. However, current molecular clock estimates indicate that Ficus is a relatively ancient genus being at least 60 million years old[4], and possibly as old as 80 million years. The main radiation of extant species, however, may have taken place more recently, between 20 and 40 million years ago.

Some better know species that represent the diversity of the genus include the Common Fig which is a small temperate deciduous tree whose fingered fig leaf is well-known in art and iconography; the Weeping Fig (F. benjamina) a hemi-epiphyte with thin tough leaves on pendulous stalks adapted to its rain forest habitat; the rough-leaved sandpaper figs from Australia; the Creeping Fig (F. pumila), a vine whose small, hard leaves form a dense carpet of foliage over rocks or garden walls. Moreover, figs with different plant habits have undergone adaptive radiation in different biogeographic regions, leading to very high levels of alpha diversity. In the tropics, it is quite common to find that Ficus is the most species-rich plant genus in a particular forest. In Asia as many as 70 or more species can co-exist.[5]

Ecology and uses

Figs are keystone species in many rainforest ecosystems. Their fruit are a key resource for some frugivores including fruit bats, capuchin monkeys, langurs and mangabeys. They are even more important for some birds. Asian barbets, pigeons, hornbills, fig-parrots and bulbuls are examples of taxa that may almost entirely subsist on figs when these are in plenty. Many Lepidoptera caterpillars, for example of several Euploea species (Crow butterflies), the Plain Tiger (Danaus chrysippus), the Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes), the Brown Awl (Badamia exclamationis), and Chrysodeixis eriosoma, Choreutidae and Copromorphidae moths feed on fig leaves. The Citrus long-horned beetle (Anoplophora chinensis), for example, has larvae that feed on wood, including that of fig trees; it can become a pest in fig plantations. Similarly, the Sweet Potato Whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) is frequently found as a pest on figs grown as potted plants and is spread through the export of these plants to other localities. For a list of other diseases common to fig trees, see List of foliage plant diseases (Moraceae).

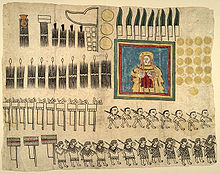

The wood of fig trees is often soft and the latex precludes its use for many purposes. It was used to make mummy caskets in Ancient Egypt. Certain fig species (mainly F. cotinifolia, F. insipida and F. padifolia) are traditionally used in Mesoamerica to produce papel amate (Nahuatl: āmatl). Mutuba (F. natalensis) is used to produce barkcloth in Uganda. Pou (F. religiosa) leaves' shape inspired one of the standard kbach rachana, decorative elements in Cambodian architecture. Weeping Fig (F. benjamina) and Indian Rubber Plant (F. elastica) are identified as powerful air-cleaning plants in the NASA Clean Air Study. Indian Banyan (F. bengalensis) and the Indian Rubber Plant, as well as other species, have use in herbalism. The latter is known to be a hyperaccumulator of benzene and methane[dubious – discuss], and urban or potted plants should be considered toxic for that reason.

Figs have figured prominently in some human cultures. There is evidence that figs, specifically the Common Fig (F. carica) and Sycamore Fig (F. sycomorus), were among the first — if not the very first — plant species that were deliberately bred for agriculture in the Middle East, starting more than 11,000 years ago. Nine subfossil F. carica figs dated to about 9400–9200 BC were found in the early Neolithic village Gilgal I (in the Jordan Valley, 13 km north of Jericho). These were a parthenocarpic type and thus apparently an early cultivar. This find predates the cultivation of grain in the Middle East by many hundreds of years.[6].

Cultural and spiritual significance

Fig trees have profoundly influenced culture through several religious traditions. Among the more famous species are the Sacred Fig tree (Peepul, Bodhi, Bo, or Po, Ficus religiosa) and the Banyan Fig (Ficus benghalensis). The oldest living plant of known planting date is a Ficus religiosa tree known as the Sri Maha Bodhi planted in the temple at Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka by King Tissa in 288 BC. It is one of the two sacred trees of Islam, and there is a sura in Quran named "The Fig" or At-Tin(سوره تین), and in East Asia, figs are pivotal in Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. Siddhārtha Gautama, the Supreme Buddha, is traditionally held to have found bodhi (enlightenment) while meditating under a Sacred Fig (F. religiosa). The same species was Ashvastha, the "world tree" of Hinduism. The Plaksa Pra-sravana was said to be a fig tree between the roots of which the Sarasvati River sprang forth; it is usually held to be a Sacred Fig but more probably seems to be a Wavy-leaved Fig (F. infectoria). The Common Fig tree is cited in the Bible, where in Genesis 3:7, Adam and Eve cover their nakedness with fig leaves. The fig fruit is also included in the list of food found in the Promised Land, according to the Torah (Deut. 8). Other important plants reported included: wheat, barley, grapes, pomegranates, olives, and dates (representing the honey). Jesus cursed a fig tree for bearing no fruit (Mark 11:12–14). The fig tree was sacred in ancient Cyprus where it was a symbol of fertility.

Fig pollination and fig fruit

Many are grown for their fruits, though only Ficus carica is cultivated to any extent for this purpose. Furthermore, the fig fruits, important as both food and traditional medicine, contain laxative substances, flavonoids, sugars, vitamins A and C, acids and enzymes. However, figs are skin allergens, and the sap is a serious eye irritant. The fig is commonly thought of as fruit, but it is properly the flower of the fig tree. It is in fact a false fruit or multiple fruit, in which the flowers and seeds grow together to form a single mass. The genus Dorstenia, also in the figs family (Moraceae), exhibits similar tiny flowers arranged on a receptacle but in this case the receptacle is a more or less flat, open surface.

Depending on the species, each fruit can contain up to several hundred to several thousand seeds.[7]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 310 kJ (74 kcal) | ||||

19 g | |||||

| Sugars | 16 g | ||||

| Dietary fiber | 3 g | ||||

0.3 g | |||||

0.8 g | |||||

| |||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[8] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[9] | |||||

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,041 kJ (249 kcal) | ||||

64 g | |||||

| Sugars | 48 g | ||||

| Dietary fiber | 10 g | ||||

1 g | |||||

3 g | |||||

| |||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[8] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[9] | |||||

A fig "fruit" is derived from a specially adapted type of inflorescence (an arrangement of multiple flowers). In this case, it is an involuted, nearly closed receptacle with many small flowers arranged on the inner surface. Thus the actual flowers of the fig are unseen unless the fig is cut open. In Chinese the fig is called wú huā guǒ (simplified Chinese: 无花果; traditional Chinese: 無花果), "fruit without flower"[10]. In Bengali, where the Common Fig is called dumur, it is referenced in a proverb: tumi jeno dumurer phool hoe gele ("You have become [invisible like] the dumur flower").

The syconium often has a bulbous shape with a small opening (the ostiole) at the outward end that allows access to pollinators. The flowers are pollinated by very small wasps that crawl through the opening in search of a suitable place to lay eggs. Without this pollinator service fig trees cannot reproduce by seed. In turn, the flowers provide a safe haven and nourishment for the next generation of wasps. This accounts for the frequent presence of wasp larvae in the fruit, and has led to a coevolutionary relationship. Technically, a fig fruit proper would be one of the many tiny mature, seed-bearing flowers found inside one fig — if you cut open a fresh fig, the flowers will appear as fleshy "threads", each bearing a single seed inside.

Fig plants can be monoecious (hermaphrodite) or gynodioecious (hermaphrodite and female).[11] Nearly half of fig species are gynodioecious, and have plants with inflorescences (syconium) with long styled pistillate flowers, or have plants with staminate flowers mixed with short styled pistillate flowers.[12] The long flowers styles tend to prevent wasps from laying their eggs within the ovules, while the short styled flowers are accessible for egg laying.[13]

All the native fig trees of the American continent are hermaphrodites, as well as species like Indian Banyan (F. benghalensis), Weeping Fig (F. benjamina), Indian Rubber Plant (F. elastica), Fiddle-leaved Fig (F. lyrata), Moreton Bay Fig (F. macrophylla), Chinese Banyan (F. microcarpa), Sacred Fig (F. religiosa) and Sycamore Fig (F. sycomorus).[14]

On the other hand the Common Fig (Ficus carica) is a gynodioecious plant, as well as F. aspera, Roxburgh Fig (F. auriculata), Mistletoe Fig (F. deltoidea), F. pseudopalma, Creeping Fig (F. pumila) and related species.

The hermaphrodite Common Figs are called "inedible figs" or caprifigs; in traditional culture in the Mediterranean region, they were considered food for goats (Capra aegagrus). In the female fig trees, the male flower parts fail to develop; they produce the "edible figs". Fig wasps grow in Common Fig caprifigs but not in the female syconiums because the female flower is too long for the wasp to successfully lay her eggs in them. Nonetheless, the wasp pollinates the flower with pollen from the caprifig it grew up in. When the wasp dies, it is broken down by enzymes inside the fig. Fig wasps are not known to transmit any diseases harmful to humans.

When a caprifig ripens, another caprifig must be ready to be pollinated. In temperate climes, wasps hibernate in figs, and there are distinct crops. Common Fig[verification needed] caprifigs have three crops per year; edible figs have two. The first (breba[15]) produces small fruits called olynth. Some parthenocarpic cultivars of Common Figs do not require pollination at all, and will produce a crop of figs (albeit sterile) in the absence of caprifigs or fig wasps.

There is typically only one species of wasp capable of fertilizing the flowers of each species of fig, and therefore plantings of fig species outside of their native range results in effectively sterile individuals. For example, in Hawaii, some 60 species of figs have been introduced, but only four of the wasps that fertilize them have been introduced, so only four species of figs produce viable seeds there. This is an example of mutualism, i.e. one organism (fig plant) can not propagate itself without the other one (fig wasp).

The intimate association between fig species and their wasp pollinators, along with the high incidence of a one-to-one plant-pollinator ratio have long led scientists to believe that figs and wasps are a clear example of coevolution. Morphological and reproductive behavior evidence, such as the correspondence between fig and wasp larvae maturation rates, have been cited as support for this hypothesis for many years[16]. Additionally, recent genetic and molecular dating analyses have shown a very close correspondence in the character evolution and speciation phylogenies of these two clades.[4]

Selected species

This section needs attention from an expert in Plants. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the section. (April 2008) |

- Ficus abutilifolia (Miq.) Miq. (= F. soldanella Warb.)

- Ficus adhatodifolia Schott

- Ficus aguaraguensis

- Ficus albert-smithii

- Ficus albipila — Abbey Tree, Phueng Tree, tandiran

- Ficus altissima

- Ficus amazonica

- Ficus americana

- Ficus andamanica

- Ficus angladei

- Ficus apollinaris Dugand (= F. petenensis Lundell)

- Ficus aripuanensis

- Ficus arpazusa[17]

- Ficus aspera

- Ficus aspera var. parcelli

- Ficus aurea — Florida Strangler Fig

- Ficus auriculata[verification needed] — Roxburgh Fig

- Ficus barbata — Bearded Fig

- Ficus battieri[verification needed]

- Ficus beddomei — Thavital

- Ficus benghalensis — Indian Banyan, Bengal Fig, East Indian Fig, borh (Pakistan), vad/vat/wad, nyagrodha, "indian fig"

- Ficus benjamina — Weeping Fig, Benjamin's Fig

- Ficus bibracteata

- Ficus bizanae

- Ficus blepharophylla

- Ficus bojeri

- Ficus broadwayi

- Ficus bubu Warb.

- Ficus burtt-davyi Hutch.

- Ficus calyptroceras

- Ficus capreifolia Del.

- Ficus carchiana C.C.Berg

- Ficus carica — Common Fig, anjeer (Pakistan), dumur (Bengali)

- Ficus castellviana

- Ficus catappifolia

- Ficus citrifolia — Short-leaved Fig, Wild Banyantree

- Ficus clusiifolia[verification needed]

- Ficus congesta

- Ficus cordata Thunb.

- Ficus cordata ssp. salicifolia (Vahl) Berg

- Ficus coronata — Creek Sandpaper Fig

- Ficus costaricana (Liebm.) Miq.

- Ficus cotinifolia

- Ficus crassipes — Round-leaved Banana Fig

- Ficus crassiuscula Standl.

- Ficus craterostoma Warb. ex Mildbr. & Burr.

- Ficus cristobalensis

- Ficus cyclophylla

- Ficus dammaropsis — Highland Breadfruit, kapiak (Tok Pisin)

- Ficus dendrocida

- Ficus deltoidea — Mistletoe Fig

- Ficus destruens

- Ficus drupacea

- Ficus ecuadorensis C.C.Berg

- Ficus elastica — Indian Rubber Plant, Rubber Fig, "rubber tree", "rubber plant"

- Ficus elastica cv. 'Decora'

- Ficus elastica var. variegata

- Ficus elasticoides[verification needed]

- Ficus elliotiana[verification needed]

- Ficus enormis[verification needed]

- Ficus erecta — Japanese fig, イヌビワ

- Ficus faulkneriana

- Ficus fischeri Warb. ex Mildbr. & Burr. (= F. kiloneura Hornby)

- Ficus fistulosa

- Ficus fraseri — Shiny Sandpaper Fig, White Sandpaper Fig, "figwood", "watery fig"

- Ficus fulvo-pilosa Summerh.

- Ficus gardneriana[verification needed]

- Ficus gibbosa

- Ficus gigantosyce Dugand

- Ficus gilletii[verification needed]

- Ficus glabra[verification needed]

- Ficus glaberrima

- Ficus glumosa (Miq.) Del. (=F. sonderi Miq.)

- Ficus godeffroyi

- Ficus gomelleira[verification needed]

- Ficus greenwoodii Summerh.

- Ficus greiffiana

- Ficus grenadensis

- Ficus grossularioides — White-leaved Fig

- Ficus guajavoides Lundell

- Ficus guaranitica[18]

- Ficus guianensis[19]

- Ficus hartii

- Ficus hebetifolia

- Ficus hederacea

- Ficus heterophylla

- Ficus hirsuta

- Ficus hirta Vahl

- Ficus hispida

- Ficus hispita L.

- Ficus ilicina (Sond.) Miq.

- Ficus illiberalis

- Ficus insipida

- Ficus insipida ssp. insipida

- Ficus insipida ssp. scabra

- Ficus kerkhovenii — Johore Fig [20]

- Ficus luschnathiana (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus infectoria — Wavy-leaved Fig, plaksa

- Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus krukovii

- Ficus lacor

- Ficus lacunata

- Ficus laevigata

- Ficus laevis

- Ficus lapathifolia

- Ficus lateriflora

- Ficus lauretana

- Ficus loxensis C.C.Berg

- Ficus lutea Vahl (= F. vogelii, F. nekbudu, F. quibeba Welw. ex Fical.)

- Ficus lyrata — Fiddle-leaved Fig

- Ficus macbridei[verification needed] Standl.

- Ficus maclellandii — Alii Fig or Banana-Leaf Fig

- Ficus macrocarpa[verification needed]

- Ficus macrophylla — Moreton Bay Fig

- Ficus magnifolia

- Ficus malacocarpa

- Ficus mariae[verification needed]

- Ficus masonii Horne ex Baker

- Ficus mathewsii

- Ficus matiziana

- Ficus mauritiana

- Ficus maxima

- Ficus maximoides C.C.Berg

- Ficus meizonochlamys

- Ficus mexiae

- Ficus microcarpa — Chinese Banyan, Malayan Banyan, Curtain Fig, "Indian laurel"

- Ficus microcarpa var. hillii — Hill's Fig

- Ficus microcarpa var. nitida — often considered a subspecies of F. retusa or a distinct species

- Ficus minahasae — longusei (Sulawesi[verification needed])

- Ficus mollior F.Muell. ex Benth.

- Ficus monckii

- Ficus montana — Oakleaf Fig

- Ficus muelleri

- Ficus muelleriana

- Ficus mutabilis

- Ficus mutisii Dugand

- Ficus mysorensis

- Ficus natalensis Hochst. — mutuba (Luganda)

- Ficus natalensis ssp. leprieurii

- Ficus natalensis ssp. natalensis

- Ficus neriifolia

- Ficus nervosa

- Ficus noronhae

- Ficus nota — tibig

- Ficus nymphaeifolia[verification needed]

- Ficus oapana C.C.Berg

- Ficus obliqua — Small-leaved Fig

- Ficus obtusifolia

- Ficus obtusiuscula (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus opposita — Sweet Sandpaper Fig, Sweet Fig, "figwood", "watery fig"

- Ficus organensis (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus padifolia

- Ficus pakkensis

- Ficus pallida

- Ficus palmata

- Ficus pandurata

- Ficus pantoniana — Climbing Fig

- Ficus panurensis

- Ficus pertusa

- Ficus petiolaris (= F. palmeri)

- Ficus pilosa

- Ficus piresiana Vázq.Avila & C.C.Berg

- Ficus platypoda — Desert Fig, Rock Fig

- Ficus pleurocarpa — Banana Fig, Gabi Fig, Karpe Fig

- Ficus polita Vahl

- Ficus polita ssp. polita

- Ficus prolixa G.Forst. (= F. mariannensis Merr.)

- Ficus pseudopalma Blanco

- Ficus pulchella

- Ficus pumila — Creeping Fig

- Ficus pyriformis

- Ficus racemosa — Cluster Fig, Goolar Fig, udumbara (Sanskrit), umbar (India)

- Ficus ramiflora

- Ficus religiosa — Sacred Fig, arali, bo, pipal, pippala, pimpal (etc.), pou (Cambodia), Ashvastha

- Ficus retusa — Taiwan Fig, Ginseng Fig, "Indian laurel"

- Ficus rieberiana C.C.Berg

- Ficus roraimensis

- Ficus roxburghii[verification needed]

- Ficus rubiginosa — Port Jackson Fig, Little-leaved Fig, Rusty Fig, damun (Sydney Language)

- Ficus rumphii Blume — Rumpf's Fig

- Ficus salicifolia Vahl (= F. pretoriae Burtt Davy) — Willow-leaved Fig

- Ficus salzmanniana

- Ficus sansibarica Warb.

- Ficus sarmentosa[verification needed]

- Ficus saussureana

- Ficus scabra G.Forst.

- Ficus schippii

- Ficus schultesii

- Ficus schumacheri

- Ficus sphenophylla

- Ficus stahlii

- Ficus stuhlmannii Warb.

- Ficus subpuberula

- Ficus superba

- Ficus superba var. henneana

- Ficus sur Forssk. (= F. capensis)

- Ficus sycomorus — Sycamore Fig, Fig-mulberry

- Ficus sycomorus ssp. sycomorus

- Ficus sycomorus ssp. gnaphalocarpa (Miq.) C.C. Berg

- Ficus tettensis Hutch. (= F. smutsii Verdoorn)

- Ficus thonningii

- Ficus tinctoria — Dye Fig, Humped Fig

- Ficus tobagensis

- Ficus tomentella[verification needed]

- Ficus tomentosa

- Ficus tonduzii Standl.

- Ficus tremula Warb.

- Ficus tremula ssp. tremula

- Ficus triangularis

- Ficus trichopoda Bak. (= F. hippopotami Gerstn.)

- Ficus trigona L.f.

- Ficus trigonata

- Ficus triradiata — Red-stipule Fig

- Ficus ulmifolia

- Ficus umbellata[verification needed]

- Ficus ursina

- Ficus variegata Bl.

- Ficus variegata var. chlorocarpa King

- Ficus variolosa

- Ficus velutina

- Ficus verruculosa Warb.

- Ficus virens — White Fig, pilkhan, an-borndi (Gun-djeihmi)

- Ficus virgata

- Ficus wassa

- Ficus watkinsiana — Watkins' Fig, Nipple Fig, Green-leaved Moreton Bay Fig

- Ficus yoponensis Desv.

List of famous fig trees

- Ashvastha — the world tree of Hinduism, held to be a supernatural F. religiosa

- Bodhi tree — a F. religiosa

- Charybdis Fig Tree of the Odyssey, presumably a F. carica

- Curtain Fig Tree — a F. virens

- Ficus Ruminalis — a F. carica

- Plaksa — another supernatural fig in Hinduism; usually identified as F. religiosa but probably F. infectoria

- Santa Barbara's Moreton Bay Fig Tree — a F. macrophylla

- Sri Maha Bodhi — another F. religiosa. Planted in 288 BC, the oldest human-planted tree on record

- The Great Banyan — a F. benghalensis, a clonal colony and once the largest organism known

- Vidurashwatha — "Vidura's Sacred Fig tree", a village in India named after a famous F. religiosa that until recently stood there

See also

|

|

Footnotes

- ^ "Ficus L". Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ^ Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- ^ Halevy, Abraham H. (1989), Handbook of Flowering Volume 6 of CRC Handbook of Flowering, CRC Press, p. 331, ISBN 9780849339165, retrieved 2009-08-25

- ^ a b c Rønsted et al. (2005)

- ^ Harrison (2005)

- ^ Kislev et al. (2006a, b), Lev-Yadun et al. (2006)

- ^ http://figs4fun.com/Links/FigLink006a.pdf

- ^ a b United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Denisowksi (2007)

- ^ http://waynesword.palomar.edu/dawkins.htm Armstrong, Wayne P. and Steven Disparti. 1998. A key to subgroups of dioecious* (gynodioecious) figs.

- ^ Friis, Ib; Balslev, Henrik; Selskab, Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes (2005), Plant diversity and complexity patterns: local, regional, and global dimensions:, Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, p. 472, ISBN 9788773043042, retrieved 2009-08-21

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/pss/2407790

- ^ Berg & Corner (2005)

- ^ CRFG (1996)

- ^ Machado et al. (2001)

- ^ Brazil. Described by Carauta & Diaz (2002): pp.38–39

- ^ Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina: Carauta & Diaz (2002): pp.64–66

- ^ Brazil: Carauta & Diaz (2002): pp.67–69

- ^ http://habitatnews.nus.edu.sg/heritage/changi/changitrees/index.html

References

- Berg, C.C. & Corner, E.J.H. (2005): Moraceae. In: Flora Malesiana Ser. I, vol. 17, part 2.

- California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc. (CRFG) (1996): Fig. Retrieved 2008-NOV-01.

- Carauta, Pedro; Diaz, Ernani (2002): Figueiras no Brasil. Editora UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro. ISBN 8571082502

- Denisowksi, Paul (2007): Chinese-English Dictionary — Fig. Retrieved 2008-NOV-01.

- Harrison, Rhett D. (2005): Figs and the diversity of tropical rain forests. Bioscience 55(12): 1053–1064. DOI:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[1053:FATDOT]2.0.CO;2 PDF fulltext

- Kislev, Mordechai E.; Hartmann, Anat & Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2006a): Early Domesticated Fig in the Jordan Valley. Science 312(5778): 1372. doi:10.1126/science.1125910 (HTML abstract) Supporting Online Material

- Kislev, Mordechai E.; Hartmann, Anat & Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2006b): Response to Comment on "Early Domesticated Fig in the Jordan Valley". Science 314(5806): 1683b. doi:10.1126/science.1133748 PDF fulltext

- Lev-Yadun, Simcha; Ne'eman, Gidi; Abbo, Shahal & Flaishman, Moshe A. (2006): Comment on "Early Domesticated Fig in the Jordan Valley". Science 314(5806): 1683a. doi:10.1126/science.1132636 PDF fulltext

- Lewington, Anna & Parker, Edward (1999): Ancient trees: Trees that live for 1000 years: 192. London, Collins & Brown Limited.

- Rønsted, Nina; Weiblen, George D.; Cook, James M.; Salamin, Nicholas; Machado, Carlos A. & Savoainen, Vincent (2005): 60 million years of co-divergence in the fig-wasp symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B 272(1581): 2593–2599. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3249 PDF fulltext

- Shanahan, M.; Compton, S.G.; So, Samson & Corlett, Richard (2001): Fig-eating by vertebrate frugivores: a global review. Biological Reviews 76(4): 529–572. doi:10.1017/S1464793101005760 PDF fulltext Electonic appendices

External links

- Figweb Major reference site for the genus Ficus

- Video: Interaction of figs and fig wasps Multi-award-winning documentary

- Fruits of Warm Climates: Fig

- California Rare Fruit Growers: Fig Fruit Facts

- North American Fruit Explorers: Fig

- BBC: Fig fossil clue to early farming

- Wayne's Word: Sex Determination & Life Cycle in Ficus carica

- Figs 4 Fun: The Weird Sex Life of the Fig