Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and the Belyayev circle

In November 1887, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg, Russia, to attend the Russian Symphony Concerts, a series devoted exclusively to music of Russian composers. Among works featured were the first complete performance of the final version of Tchaikovsky's First Symphony, and the premiere of the revised version of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony. Rimsky-Korsakov, with Alexander Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov and several other nationalistically-minded composers and musicians, had formed a group called the Belyayev circle. This group was named after timber merchant Mitrofan Belyayev, an amateur musician who became an influential music patron and publisher after he had taken an interest in Glazunov's work. During Tchaikovsky's visit to Saint Petersburg he spent much time in the company of these men; as a result, the somewhat fraught relationship he had previously endured with the nationalistic composer group known collectively as The Five would eventually meld into something more harmonious. This relationship would last until Tchaikovsky's death in late 1893.

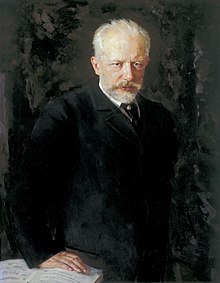

By 1887, Tchaikovsky was firmly established as one of the leading composers in Russia. A favorite of Tsar Alexander III, he was widely regarded as a national treasure. He was in demand as a guest conductor in Russia and Western Europe, and in 1890 would visit the United States in the same capacity. By contrast, the fortunes of The Five had waned, and the group had long since dispersed. Modest Mussorgsky, who had remained the most antipathetic of the group toward Tchaikovsky and his music, was dead, as was Alexander Borodin. César Cui, the composer and critic who continued to write negative reviews of Tchaikovsky's music, was seen by the composer as merely as an irritant. Mily Balakirev, the former leader of the group, lived in isolation and was confined to the musical sidelines. Of The Five, only Rimsky-Korsakov remained fully active as a composer. Now a professor of musical composition and orchestration at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, he had become a firm believer in the Western-based compositional training that had been once frowned upon by the group.

Tchaikovsky's friendship with Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov gave him increased confidence in his own abilities as a composer. His music influenced Glazunov and Anton Arensky to broaded their artistic outlooks past the nationalist agenda and to compose along more universal themes. Overall, though, Tchaikovsky's influence over the Belyayev composers was not so great, as they continued writing in a style more akin to Rimsky-Korsakov than to Tchaikovsky. While more eclectic in their approach than their predecessors in The Five, they fell back stylistically on their predecessors instead of developing individual styles, as Tchaikovsky had done. They also spread this approach to Russia on the whole and were an influence on composers well into the Soviet era.

Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov

During 1884, the 44-year-old Tchaikovsky began to shed the unsociability and restlessness that had plagued him since his abortive marriage in 1878, and which had caused him to travel incessantly throughout Russia and Western Europe. In March 1884, Tsar Alexander III conferred upon him the Order of St. Vladimir (fourth class), which carried with it hereditary nobility[1] and won Tchaikovsky a personal audience with the Tsar.[2] The Tsar's decoration was a visible seal of official approval, which helped Tchaikovsky's social rehabilitation.[1] This rehabilitation may have been cemented in the composer's mind with the success of his Third Orchestral Suite at its January 1885 premiere in St. Petersburg, under Hans von Bülow's direction.[3] Tchaikovsky wrote to Nadezhda von Meck: "I have never seen such a triumph. I saw the whole audience was moved, and grateful to me. These moments are the finest adornments of an artist's life. Thanks to these it is worth living and laboring."[4] The press was likewise unanimously favorable.[3]

While he still felt a disdain for public life, Tchaikovsky now participated in it for two reasons—his increasing celebrity, and what he felt was his duty to promote Russian music.[2] To this end, he helped support his former pupil Sergei Taneyev, now director of the Moscow Conservatory, by attending student examinations and negotiating the sometimes sensitive relations among various members of the staff.[2] Tchaikovsky also served as director of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society during the 1889–90 season. In this post, he invited a number of international celebrities to conduct, including Johannes Brahms, Antonín Dvořák and Jules Massenet.[2] Tchaikovsky promoted Russian music both in his own compositions and in his role as a guest conductor.[2] In January 1887 he substituted at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow on short notice for the first three performances of his opera Cherevichki.[5] Conducting was something the composer had wanted to master for at least a decade, as he saw that success outside Russia depended to some extent on conducting his own works.[6] Within a year of the Cherevichki performances, Tchaikovsky was in considerable demand throughout Europe and Russia, which helped him overcome a life-long stage fright and boosted his self-assurance.[7]

Tchaikovsky's relationship with Rimsky-Korsakov had gone through changes by the time he visited St. Petersburg in November 1887. As a member of The Five, Rimsky-Korsakov had been essentially self-educated as a composer, and before 1871 had not considered an academic education in musical composition to be a necessity.[8] Moreover, like the other members of The Five, Rimsky-Korsakov had regarded Tchaikovsky with suspicion since he possessed an academic background and did not agree with the musical philosophy espoused by The Five.[9] However, Rimsky-Korsakov had begun to doubt this attitude by the time he was appointed to a professorship at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1871. When he was approached about this appointment, he recognized that he was ill-prepared to take on such a task.[10] He had also reached a compositional impasse, and realized he was essentially on a creative path leading nowhere.[11] He sent a letter to Tchaikovsky in which he outlined his situation and asked what he ought to do.[12] The letter "deeply touched and amazed" Tchaikovsky with its poignancy.[13] As Tchaikovsky later relayed to Nadezhda von Meck, "Of course he had to study".[14]

Between 1871 and 1874, while he lectured at the Conservatory, Rimsky-Korsakov thoroughly grounded himself in Western compositional techniques,[15] and came to believe in the value of academic training for success as a composer.[16] Once Rimsky-Korsakov had made this turn-around, Tchaikovsky considered him an esteemed colleague, and, if not the best of friends, was at least on friendly terms with him.[17] When the other members of The Five became hostile toward Rimsky-Korsakov for his change of attitude, Tchaikovsky continued to support Rimsky-Korsakov morally, telling him that he fully applauded what Rimsky-Korsakov was doing, and admired both his artistic modesty and his strength of character.[18] Beginning in 1876, Tchaikovsky was a regiular visitor to the Rimsky-Korsakov home during his trips to Saint Petersburg.[17] At one point, Tchaikovsky offfered to have Rimsky-Korsakov appointed to the directorship of the Moscow Conservatory, but Rimsky-Korsakov refused.[17]

Tchaikovsky's admiration extended to Rimsky-Korsakov's compositions, as well. He wrote Rimsky-Korsakov that he considered Capriccio Espagnol "a colossal masterpiece of instrumentation" and called Rimsky-Korsakov "the greatest master of the present day".[19] In his diary, Tchaikovsky confided, "Read [Rimsky-]Korsakov's Snow Maiden and marveled at his mastery and was even (ashamed to admit) envious".[19]

Glazunov

Tchaikovsky was impressed not only with Rimsky-Korsakov's achievements but also those of Glazunov, who had been discovered by Balakirev and tutored by Rimsky-Korsakov in musical composition, counterpoint and orchestration.[20] He had begun showing a keen interest in Glazunov shortly after the premiere of the teenage composer's First Symphony, about which Tchaikovsky had been told by his friend Sergei Taneyev in 1882.[21] At that time, Tchaikovsky wrote Balakirev, "Glazunov interests me greatly. Is there any chance that this young man could send me the symphony so that I might take a look at it? I should also like to know whether he completed it, either conceptually or practically, with your or Rimsky-Korsakov's help".[22] Balakirev replied, "You ask about Glazunov. He is a very talented young man who studied for a year under Rimsky-Korsakov. When he composed his symphony, he did not need any help".[22] Tchaikovsky studied the score for Glazunov's First String Quartet, and wrote his brother Modest, "Despite its imitation of [Rimsky-]Korsakov ... a remarkable talent is discernable".[23] Glazunov later sent Tchaikovsky a copy of his Poème lyrique for orchestra, about which Tchaikovsky had written enthusiastically to Balakirev, and had recommended for publication to his publisher Jurgenson.[24]

According to critic Vladimir Stasov, Glazunov and Tchaikovsky first met in October 1884 at a gathering hosted by Balakirev. Tchaikovsky was in Saint Petersburg because his opera Eugene Onegin was being performed at the Mariinsky Theater. Glazunov later wrote that while the nationalists' circle "was no longer so ideologically closed and isolated as it had been earlier", they "did not consider P.I. Tchaikovsky one of our own. We valued only a few of his works, like Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, Francesca [da Rimini] and the finale of the Second Symphony. The rest of his output was either unknown or alien to us".[25] Tchaikovsky's presence won over Glazunov and the other young members present, and his conversation with them "was a fresh breeze amid our somewhat dusty atmosphere.... Many of the young musicians present, including Lyadov and myself, left Balakirev's apartment charmed by Tchaikovsky's personality.... As Lyadov put it, our acquaintance with the great composer was a real occasion."[26]

Glazunov adds that his relationship with Tchaikovsky changed from the elder composer being "not ... one of our own" to a close friendship that would last until Tchaikovsky's death.[27] "I met Tchaikovsky quite often both at Balakirev's and at my own home", Glazunov remembered. "We usually met over music. He always appeared in our social circle as one of the most welcome guests; besides myself and Lyadov, Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev were also constant members of our circle".[28] This circle, with which Tchaikovsky would spend an increasing amount of time in the last couple of years of his life, would come to be known as the Belyayev circle, named after its patron, Mitrofan Belyayev. Though his financial influence, Belyayev would shape Russian music more greatly and lastingly than either Balakirev or Stasov were able to do, and achieve the unification of Russian classical music along nationalistic lines that they had sought.[29]

Belyayev and his circle

Belyayev was one of a growing number of Russian nouveau-riche industrialists who became patrons of the arts in mid- to late-19th-century Russia; their number included Nadezhda von Meck, railway magnate Savva Mamontov and textile manufacturer Pavel Tretyakov.[30] While Nadezhda von Meck insisted on anonymity in her patronage in the tradition of noblesse oblige, Belyayev, Mamontov and Tretyakov "wanted to contribute conspicuously to public life".[31] They had worked their way up into wealth, were Slavophilic in their national outlook, and politically liberal; they believed in the greater glory of Russia, and the civil and personal rights due to the common people.[32] Because of these factors, they were more likely than the aristocracy to support native talent, and were more inclined to support nationalist artists over cosmopolitan ones.[32]

An amateur viola player and chamber music enthusiast, Belyayev hosted "quartet Fridays" at his home in Saint Petersburg. A frequent visitor to these gatherings was Rimsky-Korsakov,[33] who had met Belyayev in Moscow in 1882.[34] Belyayev became a music patron after he had heard the First Symphony by the sixteen-year-old Glazunov. Not only did Glazunov become a fixture at the "quartet Fridays", but Belyayev also published Glazunov's work and took him on a tour of Western Europe. This tour included a visit to Weimar, Germany, to present the young composer to famed Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt.[35]

Soon Belyayev became interested in other Russian composers. In 1884 he set up an annual Glinka Prize, named after pioneer Russian composer Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857). In 1885 he founded his own music publishing firm, through which he published works by Glazunov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyadov and Borodin at his own expense. At Rimsky-Korsakov's suggestion, Belyayev also founded his own concert series, the Russian Symphony Concerts, open exclusively to Russian composers. Among the works written especially for this series were the three by Rimsky-Korsakov for which he is currently best known in the West—Scheherazade, the Russian Easter Festival Overture and Capriccio Espagnol. Belyayev set up an advisory council, made up of Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov, to select which among the many composers appealing for help should be assisted, either through money, publication or performances. This council would look through the compositions and appeals submitted and suggest which were deserving of patronage and public attention.[36] Though the three worked together, Rimsky-Korsakov became the de facto leader of the group. "By force of matters purely musical I turned out to be the head of the Belyayev circle," he wrote. "As the head Belyayev, too, considered me, consulting me about everything and referring everyone to me as chief".[37]

The group of composers who now congregated with Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov were nationalistic in their outlook, as the Five before them had been. Like The Five, they believed in a uniquely Russian style of classical music that utilized folk music and exotic melodic, harmonic and rhythmic elements, as exemplified by the music of Balakirev, Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov. Unlike The Five, these composers also believed in the necessity of an academic, Western-based background in composition. The necessity of Western compositional techniques was something that Rimsky-Korsakov had instilled in many of them in his years at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.[35] Compared to the "revolutionary" composers in Balakirev's circle, Rimsky-Korsakov found those in the Belyayev circle to be "progressive ... attaching as it did great importance to technical perfection, but ... also broke new paths, though more securely, even if less speedily...."[38]

1887 visits

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts. One of these concerts included the first complete performance of his First Symphony, subtitled Winter Daydreams, in its final version.[20] Another concert featured the premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony in its revised version.[20] Before this trip, Tchaikovsky had spent considerable time corresponding with Rimsky-Korsakov, Glazunov and Lyadov, and during his visit, he spent much time in the company of these men.[39]

Nine years earlier, Tchaikovsky had penned a ruthless dissection of The Five for Nadezhda von Meck.[40] At that time, his feelings of personal isolation and professional insecurity had been at their strongest.[39] In the nine intervening years, Mussorgsky and Borodin had both died, Balakirev had banished himself to the musical sidelines, and Cui's critical missives had lost much of their sting for Tchaikovsky.[39] Rimsky-Korsakov was the only one left who was fully active as a composer, and much had changed in the intervening years between he and Tchaikovsky as a result of Rimsky-Korsakov's change in musical values.[39] Tchaikovsky had also changed. More secure as a composer and less isolated personally than he had been in the past, Tchaikovsky enjoyed the company he now kept with Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov, and found much to enjoy in their music.[41]

Tchaikovsky admired several of the pieces he heard during these concerts, including Rimsky-Korsakov's symphony and Glazunov's Second Overture on Greek Themes.[20] He promised both Glazunov and Rimsky-Korsakov that he would secure performances of their works in concerts in Moscow.[20] When these arrangements did not arise as planned, Tchaikovsky made urgent covert attempts to make good on his promises, especially to Rimsky-Korsakov, whom he now called "an outstanding figure ... worthy of every respect".[20]

In December 1887, on the eve of his departure to tour as a guest conductor through Western Europe, Tchaikovsky stopped in Saint Petersburg and consulted with Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov on a detailed program of Russian music that he might lead in Paris.[42] Though this opportunity did not arise, it shows his openness to promoting works by the Belyayev circle as his duty to promote Russian music.[42]

Lyadov

Though they had previously corresponded, Tchaikovsky made the personal acquaintance of another Rimsky-Korsakov pupil, Lyadov, during his November 1887 visit.[20] He had previously been unimpressed with Lyadov's talent. Nearly seven years earlier the publisher Besel asked Tchaikovsky's opinion about an Arabesque for solo piano that Lyadov had written. Lyadov had met with Mussorgsky's approval; in 1873, Mussorgsky had described Lyadov to Stasov as "a new, unmistakable, original and Russian young talent".[43] Tchaikovsky was not of the same opinion: "It is impossible to envisage any thing more vapid in content than this composer's music. He has many interesting chords and harmonic sequences, but not a single idea, even of the tiniest sort."[44]

Even before meeting Lyadov personally, though, Tchaikovsky may have been softening his stance. He decided to present the young composer a copy of the score of his Manfred Symphony, and once he had actually met the person whom Tchaikovsky authority David Brown called "indolent, fastidious, very private yet very engaging", his attitude toward Lyadov took a sharp turn for the better.[20] The younger composer became known as "dear Lyadov".[20]

New confidence

Two concerts Tchaikovsky heard in Saint Petersburg in January 1889, where his music shared the programs with compositions by the New Russian School (as the Belyayev circle was also called), proved a major watershed. Tchaikovsky recognized that while he had maintained good personal relations with some members of the Balakirev circle, and perhaps some respect, he had never been recognized as one of them.[45] Now with his joint participation in these concerts, he realized he was no longer excluded.[45] He wrote to Nadezhda von Meck that while he found Cui to be "an individual deeply hateful to me ... this in no way hinders me from respecting or loving such representatives of the school as Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyadov, Glazunov, or from considering myself flattered to appear on the concert platform beside them".[46] This confession showed a wholehearted willingness for Tchaikovsky to have his music heard alongside that of the nationalists.[20]

In giving this opinion, Tchaikovsky now showed not only an implicit confidence in his own music, but also the realization that it could sit comfortably and confidently alongside any number of their compositions, in no way suffering in the ears of any audience. He had nothing to fear from whatever comparisons might result.[47] Nor did he confine his views to private consumption. Tchaikovsky openly supported the musical efforts of Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov, despite a widely held view that they were musical enemies. In an interview printed in the weekly newspaper Saint Petersburg Life (Petersburgkaia zhizn') in November 1892, he said,

According to the view that is widespread among the Russian music public, I am associated with the party that is antagonistic to the one living Russian composer I love and value above all others—Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.... In a word, despite our different musical identities, it would seem we are following a single path; and I, for my part, am proud to have such a fellow traveler.... Lyadov and Glazunov are also numbered among my opponents, yet I sincerely love and value their talent.[48]

With this new-found confidence came increased contact between Tchaikovsky and the Belyayev circle.[49] Rimsky-Korsakov wrote, "In the winter of spring of 1891 [actually 1890[50]] Tchaikovsky came to Saint Petersburg on quite a long visit, and from then dated his closer intimacy with Belyayev's circle, particularly with Glazunov, Lyadov, and me. In the years following, Tchaikovsky's visits became quite frequent."[51]

Mixed feelings

While Glazunov and Lyadov were friendly with Tchaikovsky and were charmed by him, Rimsky-Korsakov found the situation more complex.[52] Memories persisted of the old friction between Tchaikovsky and The Five, and Rimsky-Korsakov also observed, with some annoyance, how Tchaikovsky became increasingly popular among Rimsky-Korsakov's followers.[53] The personal jealousy Rimsky-Korsakov felt was compounded by a professional one. As he writes in his memoirs,

At this time [approximately 1890] there begins to be noticeable a considerable cooling off and even somewhat inimical attitude toward the memory of the "mighty kuchka" of Balakirev's period. On the contrary a worship of Tchaikovsky and a tendency toward eclecticism grew even stronger. Nor could one help noticing the predilection (that sprang up then in our circle) for Italian-French music of the time of wig and farthingale [that is, the eighteenth century], music introduced by Tchaikovsky in his Queen of Spades and Iolanthe. By this time quite an accretion of new elements and young blood had accumulated in Byelayev's circle. New times, new birds, new songs.[54]

Rimsky-Korsakov mentions Tchaikovsky's triumph over the Five with a seeming generosity—while he remained genial in public, he had developed a jealous resentment of Tchaikovsky's greater fame.[55] Publicly, he remained genial toward Tchaikovsky. Privately, though, he confessed his fears to his friend, the Moscow critic Semyon Kruglikov:

Tchaikovsky has told me that he intends (maybe it's a secret) to leave Moscow and transfer his center of gravity to St. Petersburg. This fact is very portentous. The minute he chooses St. Petersburg for his settled existence, a circle will immediately form around him, which Lyadov and Glazunov will certainly join, and after them many others. And Laroche will be there too, clever as ever. Tchaikovsky, with his inborn worldly tact, seduces everyone and surrounds himself with talented people. For Tchaikovsky it's very pleasant. The new circle will border on a Rubinstein cult. Don't forget that Lyadov is already strongly under Rubinstein's influence. Do you know Tchaikovsky's tastes? Laroche's? Rubinstein's tastes and convictions? And all the spaces that remain will be filled with all kinds of worthless hangers-on and faceless adorers. And so there you are, our youth will drown (and not only our youth—look at Lyadov) in a sea of eclecticism that will rob them of their individuality.[56]

Hermann Laroche was a noted Russian music critic and friend of Tchaikovsky whose views and those of the New Russian School did not coincide.[57] Anton Rubinstein was a well-known, musically conservative composer who likewise did not agree with the nationalists' music or their philosophy, but who was extremely popular as both a composer and a virtuoso pianist.[58] Another letter to Kruglikov goes further about Laroche's influence on Glazunov and Lyadov: "It's disgusting to see how Laroche has ingratiated himself with everyone. Only in my presence do they refrain from falling all over him.... Lyadov abuses the New Russian School. Right now that's fashionable around here. Glazunov does the same; they all do. They're all spitting in the well from which they used to drink. There's Laroche's influence for you".[59]

Even with these private reservations, when Tchaikovsky attended Rimsky-Korsakov's nameday party in May 1893, along with Belyayev, Glavunov and Lyadov, Rimsky-Korsakov asked Tchaikovsky personally if he would conduct four concerts of the Russian Musical Society in Saint Petersburg the following season. After some hesitation, Tchaikovsky agreed.[60] As a condition for Tchaikovsky's engagement, the Russian Musical Society required a list of works that he planned to conduct. Among the items on the list Tchaikovsky supplied were Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony and Glazunov's orchestral fantasy The Forest.[61]

At the first of these appearances, on October 28, 1893, Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, along with his First Piano Concerto with Adele Aus der Ohe as soloist.[62] Tchaikovsky did not live to conduct the other three concerts, as he died on November 6, 1893.[63] Rimsky-Korsakov stood in for him at the second of these events, an all-Tchaikovsky concert in memory of the composer, on December 12, 1893. The program included the Fourth Symphony, Francesca da Rimini, Marche Slave plus some solo piano works played by Felix Blumenfeld.[64]

Legacy

While the Belyayev circle remained a nationalistic school of composition, its exposure to Tchaikovsky and his music made it more readily amenable to Western practices of composition, producing works that were a synthesis of nationalist tradition and Western technique.[54][65] Glazunov's reaction was typical. He began to study Tchaikovsky's works and "found much that was new ... that was instructive for us as young musicians. It struck me that Tchaikovsky, who was above all a lyrical and melodic composer, had introduced operatic elements into his symphonies. I admired the thematic material of his works less than the inspired unfolding of his thoughts, his temperament and the constructural perfection."[66] This study influenced Glazunov in writing his Third Symphony, which is dedicated to Tchaikovsky. Although the earliest sketches of this work date to 1883, the symphony was an effort by Glazunov to reach beyond the nationalist style to reflect what he felt were universal forms, moods and themes.[67] Tchaikovsky's influence is clear, especially in the work's lyrical episodes,[67] in its themes and key relations, reminiscent of Tchaikovsky's Fourth and Fifth Symphonies,[68] and in its orchestration, full of "dark doublings" and subtle instrumental effects.[68] Glazunov's study of Tchaikovsky's works may have also influenced him to write ballets for Marius Petipa, an action unheard-of in the nationalist circle.[68]

Anton Arensky is another case in point. He studied with Rimsky-Korsakov at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and at 21, in 1882, became professor of composition at the Moscow Conservatory. He remained active there as a teacher and composer for the next 13 years. He also sought out compositional advice from Tchaikovsky, who corresponded with Arensky and gave the younger composer much practical advice and encouragement.[69] Despite his reputation as a Moscow composer, he actually produced the majority of his work in Saint Petersburg after succeeding Balakirev as director of the Imperial Chapel in 1895. In his instrumental work, Arensky considered himself a successor to Tchaikovsky. However, musicologist Francis Maes asserts that in Arensky's compositions, there is "a dichotomy between the model of Rimsky-Korsakov and that of Tchaikovsky".[70] In his first opera, Son of the Volga, Arensky focuses on the folkloristic aspect of the plot as his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov would have done, instead of on the love story.[70] Arensky models his second opera, Raphael, after Tchaikovsky's opera Iolanta, producing "a saccharine fantasy about the famous painter" who, when accused of seducing his model, dispels doubts about the purity of his intentions by unveiling her portrait as the Mother of God.[70]

Overall, however, the degree of influence Tchaikovsky's music had on the Belyayev composers was not great. They generally continued stylistically from where The Five stopped, falling back on clichés and mannerisms taken from the works of Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev.[35] Moreover, the musical scene in St. Petersburg came to be dominated by this group of young composers, especially since Rimsky-Korsakov had taught many of them at the Conservatory there. Composers who wished to be part of this circle and who desired Belyayev's patronage had to write in a musical style approved by Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov. Because of this, Rimsky-Korsakov's style became the preferred academic style—one that young composers had to follow if they hoped to have any sort of career.[36] This bias would continue at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory after Rimsky-Korsakov's retirement in 1906, with his son-in-law Maximilian Steinberg in charge of composition classes at the Conservatory through the 1920s.[71] Dmitri Shostakovich would complain about Steinberg's musical conservatism, typified by such phrases as "the inviolable foundations of the kuchka", and the "sacred traditions of Nikolai Andreyevich [Rimsky-Korsakov]".[72] (Kuchka, short for Moguchaya kuchka or "Mighty Handful", was another name for The Five.) Nor was this traditionalism limited to Saint Petersburg. Well into the Soviet era, many other music conservatories remained run by traditionalists such as Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov in Moscow and Reinhold Glière in Kiev. "As a result," Maes writes, "the conservatories retained a direct link with the Belyayev aesthetic".[73]

Notes

- ^ a b Brown, New Grove, 18:621.

- ^ a b c d e Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:162.

- ^ a b Brown, Man and Music, 275.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Man and Music, 275.

- ^ Holden, 261; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 197.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 133.

- ^ Holden, 266; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 232.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 228.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 75.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 117.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 228–229; Rimsky-Korsakov, 117–118.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 228–229; Taruskin, 30.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 228.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Crisis Years, 229.

- ^ Abraham, New Grove (1980), 16:29.

- ^ Maes, 170; Rimsky-Korsakov, 119.

- ^ a b c Taruskin, 31.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 157 ft. 30.

- ^ a b As quoted by Taruskin, 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brown, Final Years, 91.

- ^ Lobanova, 4

- ^ a b Quoted in Lobanova, 4.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Wandering, 225.

- ^ Brown, Wandering, 291.

- ^ As quoted in Taruskin, 37.

- ^ As quoted in Taruskin, 37–38.

- ^ Taruskin, 38.

- ^ As quoted in Poznansky, Eyes, 141.

- ^ Taruskin, 51.

- ^ Figes, 195–197; Maes, 173–174, 196–197.

- ^ Taruskin, 49.

- ^ a b Taruskin, 42.

- ^ Maes, 172–173.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 261.

- ^ a b c Maes, 192.

- ^ a b Maes, 173.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 288.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 286–287.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Final Years, 90.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 228–230.

- ^ Brown, Final Years, 90–91.

- ^ a b Brown, Final Years, 125.

- ^ Spencer, New Grove, 11:383.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Final Years, 91.

- ^ a b Brown, Final Years, 172.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Final Years, 90–91

- ^ Brown, Final Years, 90–91, 172.

- ^ As quoted in Poznansky, Eyes, 207—208.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 212; Rimsky-Korsakov, 308.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 309, footnote.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 308.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 564.

- ^ Poznansky, 564; Taruskin, 39.

- ^ a b Rimsky-Korsakov, 309.

- ^ Holden, 316; Taruskin, 39.

- ^ As quoted in Taruskin, 19–20.

- ^ Taruskin, 16.

- ^ Maes, 34, 36.

- ^ As quoted in Taruskin, 20.

- ^ Brown, Final Years, 465.

- ^ Brown, Final Years, 474.

- ^ Brown, Final Years, 478.

- ^ Brown, Final Years, 481; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 270.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 341.

- ^ Schwarz, New Grove (1980), 7:428.

- ^ Quoted in Lobanova, 6.

- ^ a b Lobanova, 6.

- ^ a b c Taruskin, 39.

- ^ Brown, New Grove (2001)1:868.

- ^ a b c Maes, 193.

- ^ Wilson, 37.

- ^ Letter from Shostakovich to Tatyana Glivenko dated February 26, 1924. As quoted in Fay, 24.

- ^ Maes, 244.

References

- Abraham, Gerald, "Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay Andreyevich." In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillian, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Bertensson, Sergei and Jay Leyda, with the assistance of Sophia Satina, Sergei Rachmaninoff—A Lifetime in Music (Washington Square, New York: New York University Press, 1956)). ISBN n/a.

- Brown, David, "Arensky, Anton [Antony] Stepanovich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: MacMillian, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Brown, David, "Taneyev, Sergey Ivanovich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: MacMillian, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Brown, David, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich". In The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840–1874 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978). ISBN 0-393-07535-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874–1878 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). ISBN 0-393-01707-9.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering, 1878–1885 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986). ISBN 0-393-02311-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885–1893 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991).

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007). ISBN 0-571-23194-2.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002). ISBN 0-8050-5783-8 (hc.).

- Fay, Laurel, Shostakovich: A Life (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). ISBN 0-19-518251-0.

- Frolova-Walker, Marina, "Russian Federation". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- Harrison, Max, Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings (London and New York: Continnum, 2005). ISBN 0-8264-5344-9.

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Lobanova, Marina, Notes for BIS CD 1358, Glazunov: Ballade; Symphony No. 3; BBC National Orchestra of Wales conducted by Tadaaki Otaka.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Martyn, Barrie, Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor (Aldershot, England: Scolar Press, 1990). ISBN 0-85967-809-1.

- Norris, Geoffrey, "Rachmaninoff [Rakhmaninov], Serge [Sergey] (Vasilyevich)", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: MacMillian, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). ISBN 0-02-871885-2.

- Poznansky, Alexander, tr. Ralph J. Burr and Robert Reed, Tchaikovsky Through Others' Eyes (Blooomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1999). ISBN 0-253-33545-0.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai, Letoppis Moyey Muzykalnoy Zhizni (St. Petersburg, 1909), published in English as My Musical Life (New York: Knopf, 1925, 3rd ed. 1942). ISBN n/a.

- Schwarz, Boris, "Glazunov, Alexander Konstantinovich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillian, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Spencer, Jennifer, "Lyadov [Liadov], Anatol [Anatoly] Konstantinovich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London: Macmillian, 1980), 20 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-23111-2

- Taruskin, Richard, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works Through Mavra, Volume 1 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-198-16250-2.

- Volkoff, Vladimir, Tchaikovsky: A Self Portrait (Boston: Crescendo Publishing Company, 1975).

- Volkov, Solomon, tr. Bouis, Antonina W., St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1995). ISBN 0-02-874052-1.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). SBN 684-13558-2.

- Wiley, Roland John. "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillian, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Wilson, Elizabeth, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Second Edition (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994, 2006). ISBN 0-691-12886-3.