Central Park

| Central Park | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°47′N 73°58′W / 40.783°N 73.967°W |

| Opened | 1859 |

| Operated by | Central Park Conservancy |

| Status | Open all year |

Central Park | |

| Built | 1857 |

|---|---|

| Architect | Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000538 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | May 23, 1963 |

Central Park is a public urban park in the heart of Manhattan in New York City in the United States. It is host to approximately twenty-five million visitors each year. Central Park was opened in 1859, completed in 1873 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1963. Eighty-five percent of the park's operating budget comes from private sources via the Central Park Conservancy, which manages the park pursuant to a contract with New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.[2]

Central Park today

Central Park covers an area of 843 acres (3.41 km2; 1.317 sq mi). It is 2.5 miles (4 km) long between 59th Street (Central Park South) and 110th Street (Central Park North), and 0.5 miles (0.8 km) wide between Fifth Avenue and Central Park West. It is similar in size to San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, Chicago's Lincoln Park, Vancouver's Stanley Park and Munich's Englischer Garten; it is just over one third of the size of London's Richmond Park. The park hosts approximately twenty-five million visitors annually, and is the most visited city park in the United States[3] The park's frequent appearance in many movies and television shows has made it famous.

The park is maintained by the Central Park Conservancy, a private, not-for-profit organization that manages the park under a contract with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation,[2] in which the president of the Conservancy is ex officio Administrator of Central Park.

Central Park is bordered on the north by West 110th Street, on the south by West 59th Street, on the west by Eighth Avenue. Along the park's borders however, these are known as Central Park North, Central Park South, and Central Park West, respectively. Fifth Avenue retains its name along the eastern border of the park. Most of the areas immediately adjacent to the park are known for impressive buildings and valuable real estate.

The park was designed by landscape designer and writer Frederick Law Olmsted, and English architect Calvert Vaux, who went on to collaborate on Brooklyn's Prospect Park. Central Park has been a National Historic Landmark since 1963.[4][5][6]

While foliage in much of the park appears natural, it is in fact almost entirely landscaped. The park contains several natural-looking lakes and ponds,[7] extensive walking tracks, bridle paths, two ice-skating rinks (one of which is a swimming pool in July and August), the Central Park Zoo, the Central Park Conservatory Garden, a wildlife sanctuary, a large area of natural woods, a 106-acre (43 ha) billion gallon reservoir with an encircling running track, and an outdoor amphitheater called the Delacorte Theater which hosts the "Shakespeare in the Park" summer festivals. Indoor attractions include Belvedere Castle with its nature center, the Swedish Cottage Marionette Theatre, and the historic Carousel. In addition there are numerous major and minor grassy areas, some of which are used for informal or team sports, some are set aside as quiet areas, and there are a number of enclosed playgrounds for children.

The park has its own wildlife and also serves as an oasis for migrating birds, especially in the Fall and Spring, making it a significant attraction for bird watchers; 200 species of birds are regularly seen.[8] The 6 miles (10 km) of drives within the park are used by joggers, bicyclists, skateboarders, and inline skaters, especially on weekends and in the evenings after 7:00 p.m., when automobile traffic is banned.

The real estate value of Central Park was estimated by property appraisal firm Miller Samuel to be $528,783,552,000 in December 2005.[9]

History

Early history

The park was not a part of the Commissioners' Plan of 1811; however, between 1821 and 1855, New York City nearly quadrupled in population. As the city expanded, people were drawn to the few open spaces, mainly cemeteries, to get away from the noise and chaotic life in the city.[10] Before long, however, New York City's need for a great public park was voiced by the poet and editor of the Evening Post (now the New York Post), William Cullen Bryant and by the first American landscape architect, Andrew Jackson Downing, who began to publicize the city's need for a public park in 1844. A stylish place for open-air driving, like the Bois de Boulogne in Paris or London's Hyde Park, was felt to be needed by many influential New Yorkers, and in 1853 the New York legislature designated a 700-acre (280 ha) area from 59th to 106th Streets for the creation of the park, at a cost of more than US$5 million for the land alone.

Initial development

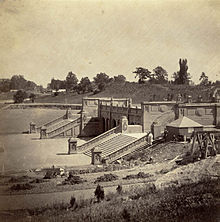

The state appointed a Central Park Commission to oversee the development of the park, and in 1857 the commission held a landscape design contest. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux developed what came to be known as the "Greensward Plan," which was selected as the winning design.

According to Olmsted, the park was "of great importance as the first real Park made in this century—a democratic development of the highest significance…," a view probably inspired by his stay, and various trips in Europe in 1850.[12] During that stay he visited several parks and was particularly impressed by Birkenhead Park and Derby Arboretum in England.

Several influences came together in the design. Landscaped cemeteries, such as Mount Auburn (Cambridge, Massachusetts) and Green-Wood (Brooklyn, New York) had set examples of idyllic, naturalistic landscapes. The most influential innovations in the Central Park design were the "separate circulation" systems for pedestrians, horseback riders, and pleasure vehicles. The "crosstown" commercial traffic was entirely concealed in sunken roadways, (today called "transverses"), screened with densely planted shrub belts so as to maintain a rustic ambience.

The Greensward plan called for some 36 bridges, all designed by Vaux, ranging from rugged spans of Manhattan schist or granite, to lacy neo-gothic cast iron, no two alike. The ensemble of the formal line of the Mall's doubled allées of elms culminating at Bethesda Terrace, whose centerpiece is the Bethesda Fountain, with a composed view beyond of lake and woodland, was at the heart of the larger design.

Before the construction of the park could start, the area had to be cleared of its inhabitants, most of whom were quite poor and either free African-Americans or immigrants of either German or Irish origin. Most of them lived in smaller villages, such as Seneca Village, Harsenville, the Piggery District or the Convent of the Sisters of Charity. Around 1,600 working-class residents occupying the area at the time were evicted under the rule of eminent domain during 1857, and Seneca Village, and parts of the other communities were razed to make room for the park.

During the construction of the park, Olmsted fought constant battles with the Park Commissioners, many of whom were appointees of the city's Democratic machine. In 1860, he was forced out for the first of many times as Central Park's Superintendent, and Andrew Haswell Green, the former president of New York City's Board of Education took over as the chairman of the commission. Despite the fact that he had relatively little experience, he still managed to accelerate the construction, as well as to finalize the negotiations for the purchase of an additional 65 acres (260,000 m2) at the north end of the park, between 106th and 110th Streets, which would be used as the "rugged" part of the park, its swampy northeast corner dredged and reconstructed as the Harlem Meer.

Between 1860 and 1873, most of the major hurdles to construction were overcome, and the park was substantially completed. During this period, more than 18,500 cubic yards (14,000 m³) of topsoil had been transported in from New Jersey, as the original soil was not fertile or substantial enough to sustain the various trees, shrubs, and plants the Greensward Plan called for. When the park was officially completed in 1873, more than ten million cartloads of material had been transported out of the park, including soil and rocks. More than four million trees, shrubs and plants representing approximately 1,500 species were transplanted to the park.

More gunpowder was used to clear the area than was used at the battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War.[13]

Sheep grazed on the Sheep Meadow from the 1860s until 1934, when they were moved upstate as it was feared they would be used for food by impoverished Depression-era New Yorkers.[14]

20th century

1900 - 1960

Following completion, the park quickly slipped into decline. One of the main reasons for this was the lack of interest of the Tammany Hall political machine, which was the largest political force in New York at the time.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the park faced several new challenges. Cars were becoming commonplace, bringing with them their burden of pollution, and people's attitudes were beginning to change. No longer were parks to be used only for walks and picnics in an idyllic environment, but now also for sports, and similar recreation. Following the dissolution of the Central Park Commission in 1870 and Andrew Green's departure from the project, and the death of Vaux in 1895, the maintenance effort gradually declined, and there were few, if any, attempts to replace dead trees, bushes and plants, or worn-out lawn. For several decades, authorities did little or nothing to prevent vandalism and the littering of the park.

All of this changed in 1934, when Republican Fiorello La Guardia was elected mayor of New York City and unified the five park-related departments then in existence. Robert Moses was tasked with cleaning up the park. Moses, about to become one of the mightiest men in New York City, took over what was essentially a relic, a leftover from a bygone era.

According to historian Robert Caro in his 1974 book The Power Broker:

- Lawns, unseeded, were expanses of bare earth, decorated with scraggly patches of grass and weeds, that became dust holes in dry weather and mud holes in wet…. The once beautiful Mall looked like a scene of a wild party the morning after. Benches lay on their backs, their legs jabbing at the sky...

In a single year, Moses managed to clean up Central Park and other parks in New York City: lawns and flowers were replanted; dead trees and bushes were replaced; walls were sandblasted and bridges repaired. Major redesigning and construction was also carried out: for instance, the Croton Lower Reservoir was filled in so the Great Lawn could be created. The Greensward Plan's purpose of creating an idyllic landscape was combined with Moses' vision of a park to be used for recreational purposes—nineteen playgrounds, twelve ballfields, and handball courts were constructed. Moses also managed to secure funds from the New Deal program, as well as donations from the public.

1960–1980

The 1960s marked the beginning of an “Events Era” in Central Park that reflected the widespread cultural and political trends of the period. The Public Theater's annual Shakespeare in the Park festival was settled in the Delacorte Theater (1961), and summer performances were instituted on the Sheep Meadow, and then on the Great Lawn by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the Metropolitan Opera. Increasingly through the 1970s, the park became a venue for events of unprecedented scale, including political rallies and demonstrations, festivals, and massive concerts.

New York City was experiencing economic and social upheaval. Residents were fleeing the city and moving to the suburbs. Morale was low, and crime was high. The Parks Department, suffering from budget cuts and a lack of skilled management that rendered its workforce virtually ineffective, responded by opening the park to any and all activities that would bring people into it—regardless of their impact and without adequate management, oversight or maintenance follow-up. Some of these events became important milestones in the social history of the park and the cultural history of the city. Many were positive experiences fondly remembered by the individuals who participated, but without essential management and enforcement of reasonable limitations, and combined with a total lack of park maintenance and repair, they also did an incredible amount of damage.

By the mid-1970s, New York’s fiscal and social malaise had contributed to severe managerial neglect. "Years of poor management and inadequate maintenance had turned a masterpiece of landscape architecture into a virtual dustbowl by day and a danger zone by night," said the Conservancy president.[15] Time had hastened the deterioration of its infrastructure and architecture, and ushered in an era of vandalism, territorial use (as when a pick-up game of softball or soccer commandeered open space to the exclusion of others) and illicit activities.

Several citizen groups had emerged, intent upon reclaiming the park by fundraising and organizing volunteer initiatives. One of these groups, the Central Park Community Fund, commissioned a study of the park’s management. the study's conclusion was bi-linear;

- It called for the establishment of a single position within the Parks Department, responsible for overseeing both the planning and management of Central Park and

- for a board of guardians to provide citizen oversight.

In 1979 Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis established the Office of Central Park Administrator, appointing to the position the executive director of another citizen organization, the Central Park Task Force. The Central Park Conservancy was founded the following year, to support the office and initiatives of the Administrator and to provide consistent leadership through a self-perpetuating, citizen-based board that would also include as ex-officio trustees the Parks Commissioner, Central Park Administrator, and mayoral appointees.

1980–present

Under the leadership of the Central Park Conservancy, the park's reclamation began with modest but highly significant first steps, addressing needs that could not be met within the existing structure and resources of the Parks Department. Interns were hired, and a small restoration staff to reconstruct and repair unique rustic features, undertaking horticultural projects, and removing graffiti under the broken windows premise. Currently, "Graffiti doesn't last 24 hours in the park," according to Conservancy president Douglas Blonsky.[16]

By the early 1980s the Conservancy was engaged in design efforts and long-term restoration planning, using both its own staff and external consultants. It provided the impetus and leadership for several early restoration projects funded by the City, preparing a comprehensive plan for rebuilding the park. On completion of the planning stage in 1985, the Conservancy launched its first "Capital" campaign, assuming increasing responsibility for funding the park's restoration, and full responsibility for designing, bidding, and supervising all capital projects in the park.

The restoration was accompanied by a crucial restructuring of management, whereby the park was subdivided into zones, to each of which a supervisor was designated, responsible for maintaining restored areas. Citywide budget cuts in the early 1990s, however, resulted in attrition of the park's routine maintenance staff, and the Conservancy began hiring staff to replace these workers. Management of the restored landscapes by the Conservancy’s "zone gardeners" proved so successful that core maintenance and operations staff were reorganized in 1996. The zone-based system of management was implemented throughout the park, which was divided into 49 zones. Consequently, every zone of the park has a specific individual accountable for its day-to-day maintenance. Zone gardeners supervise volunteers[17] assigned to them, (who commit to a consistent work schedule), and are supported by specialized crews in areas of maintenance requiring specific expertise or equipment, or more effectively conducted on a parkwide basis.

Today the Conservancy employs four out of five maintenance and operations staff in the park. It effectively oversees the work of both the private and public employees under the authority of the Central Park Administrator, (publicly appointed), who reports to the Parks Commissioner, Conservancy's president. As of 2007, the Conservancy had invested approximately $450 million in the restoration and management of the park; the organization presently contributes approximately 85% of Central Park’s annual operating budget of over $25 million.[2]

The system was functioning so well that in 2006 the Conservancy created the Historic Harlem Parks initiative, providing horticultural and maintenance support and mentoring in Morningside Park and St. Nicholas, Jackie Robinson and Marcus Garvey Parks.[18]

Activities

Carriage horses

New York City has had carriage horses since they were revived in 1935.[19] The carriages have appeared in many films, and the first female horse and carriage driver, Maggie Cogan, appeared in a Universal newsreel in 1967.[20] As such, they have become a symbolic institution of the city. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, in a much-publicized event, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani went to the stables himself to ask the drivers to go back to work to help return a sense of normality.[19]

Some activists and politicians have questioned the ethics of this tradition.[21] The history of accidents involving spooked horses has come under scrutiny with recent horse deaths.[22] Protests from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, and celebrities including Alec Baldwin, Alecia Beth Moore and Cheryl Hines have raised the issue's profile.[23][24] Additional media accounts have corroborated some charges, but they have also shown that the standards vary from stable to stable.[25]

Both activists and horse owners who pride themselves on humane conditions agree that part of the problem is lack of enforcement of the city code.[25] Supporters of the trade say it needs to be reformed, not shut down, and that carriage drivers deserve a raise, which the city has not authorized since 1989.[26] Paris, London, Beijing, and several U.S. cities have banned carriage horses.[27]

Pedicabs

Pedicabs have more recently offered visitors a more dynamic way in which to view the park. Covering three to ten times the distance of a typical Central Park horse carriage ride, pedicabs have become very popular with visitors and New Yorkers alike in the last five years.[28]

Sports

Park Drive, just over 6 miles (9.7 km) long, is a haven for runners, joggers, bicyclists, and inline skaters. Most weekends, races take place in the park, many of which are organized by the New York Road Runners. The New York City Marathon finishes in Central Park outside Tavern on the Green. Many other professional races are run in the park, including the recent, (2008), USA Men's 8k Championships.

A long tradition of horseback riding in the park was kept alive by the one remaining stable nearby, Claremont Riding Academy until it closed in 2007. At the northern part of Central Park between 106th and 108th streets Lasker Rink and Pool is a large ice skating rink which converts to an outdoor swimming pool in summer.

Entertainment

Each summer, the Public Theater presents free open-air theatre productions, often starring well-known stage and screen actors. The Delacorte Theater is the summer performing venue of the New York Shakespeare Festival. Most, though not all, of the plays presented are by William Shakespeare, and the performances are generally regarded as being of high quality since its founding by Joseph Papp in 1962.

The New York Philharmonic gives an open-air concert every summer on the Great Lawn, and the Metropolitan Opera presents two operas. Many concerts have been given in the park including The Supremes, 1970; Carole King, 1973; Bob Marley & The Wailers, 1975; Elton John, 1980; the Simon and Garfunkel reunion, 1981; Diana Ross, 1983; Garth Brooks, 1997; Dave Matthews Band, 2003, Bon Jovi 2008.[29] Since 1992, local singer-songwriter David Ippolito has performed almost every summer weekend to large crowds of passers-by and regulars and has become a New York icon, often simply referred to as "That guitar man from Central Park."

Each summer, City Parks Foundation offers Central Park Summerstage, a series of free performances including music, dance, spoken word, and film presentations. SummerStage will celebrate its 25th anniversary in 2010. Throughout its history Summerstage has welcomed emerging artists and world renowned artists, including Celia Cruz, David Byrne, Curtis Mayfield, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, George Clinton and the P-Funk All Stars, and Nobel Laureate and Pulitzer winner Toni Morrison, Femi Kuti, Seun Kuti, Pulitzer winner Junot Diaz, Vampire Weekend, Dayton Contemporary Dance Company, Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company, and many more.

With the revival of the city and the park in the new century, Central Park has given birth to arts groups dedicated to performing in the park, notably Central Park Brass, which performs an annual concert series and the New York Classical Theatre, which produces an annual series of plays.

Central Park was home to the famed New York City restaurant Tavern on the Green which was located on the park's grounds at Central Park West and West 67th Street. Tavern on the Green had its last seating on December 31, 2009 before closing its doors.

Central Park was home to the largest concert ever on record. Country Superstar Garth Brooks performed a free concert in August 1997. About 980,000 attended the event, according to the FDNY.[30]

Climbing

Central Park's glaciated rock outcroppings attract climbers, especially boulderers; Manhattan's bedrock, a glaciated schist, protrudes from the ground frequently and considerably in some parts of Central Park. The two most renowned spots for boulderers are Rat Rock and Cat Rock; others include Dog Rock, Duck Rock, Rock N' Roll Rock, and Beaver Rock, near the south end of the park.[31]

Children

In addition to its 37 unique playgrounds, Central Park offers dozens of activities for children, including performances by master puppeteers at the historic Swedish Cottage Marionette Theatre. There are other activities such as children's yoga, modern art classes for infants, and wind chime making classes. The famous Central Park Carousel has excited and thrilled children since the original one was built in 1870. The current carousel was moved to its Central Park location from Coney Island in the 1950s and is considered one of the finest merry-go-rounds in America. [32]

Sculptures

Though Olmsted disapproved of the clutter of sculptures in the park, a total of twenty-nine sculptures have been erected over the years, most of which have been donated by individuals or organizations. Much of the first statuary to appear in the park was of authors and poets, clustered along a section of the Mall that became known as Literary Walk. The better-known sculptors represented in Central Park include Augustus Saint-Gaudens and John Quincy Adams Ward. The "Angel of the Waters" at Bethesda Terrace by Emma Stebbins (1873), was the first large public sculpture commission for an American woman. The 1925 statue of the sled dog Balto who became famous during the 1925 serum run to Nome, Alaska is very popular among tourists, reflected in its near polished appearance as the result of being patted by countless visitors. The oldest sculpture is "Cleopatra's Needle," actually an Egyptian obelisk of Tutmose III much older than Cleopatra, which was donated to New York by the Khedive of Egypt. The largest and most impressive is equestrian King Jagiello bronze monument on the east end of Turtle Pond. North of Conservatory Water, the sailboat pond, there is a larger-than-life statue of Alice in Wonderland, sitting on a huge mushroom playing with her cat, while the Hatter and the March Hare look on. A large memorial to Duke Ellington created by sculptor Robert Graham was dedicated in 1997 near Fifth Avenue and 110th Street, in the Duke Ellington Circle.

For 16 days in 2005 (February 12–27), Central Park was the setting for Christo and Jeanne-Claude's installation The Gates. Though the project was the subject of very mixed reactions (and it took many years for Christo and Jeanne-Claude to get the necessary approvals), it was nevertheless a major, if temporary, draw for the park.[33]

Crime

Although often regarded as a kind of oasis of tranquility inside a "city that never sleeps," Central Park was once a very dangerous place - especially after dark - as measured by crime statistics.[citation needed] The park, like much of New York City, is considerably safer today, though during prior periods it was the site of numerous muggings and rapes.[citation needed] Well-publicized incidents of sexual and confiscatory violence, such as the notorious 1989 "Central Park Jogger" case, dissuaded many from visiting one of Manhattan's most scenic areas.

As crime has declined in the park and in the rest of New York City, many of the negative perceptions have begun to wane. The park has its own New York City Police Department precinct (Central Park Precinct), which employs both regular police and auxiliary officers. In 2005, safety measures held the number of crimes in the park to fewer than one hundred per year (down from approximately 1,000 in the early 1980s). New York City Parks Enforcement Patrol also patrols Central Park.

On June 11, 2000, following the Puerto Rican Day Parade, gangs of drunken men sexually assaulted women in the park. Several arrests were made shortly after the attacks, but it was not until 2006 that a civil suit against the city for failing to provide police protection was finally settled.[34][35]

Other issues

Permission to hold issue-centered rallies in Central Park has been met with increasingly stiff resistance from the city. In 2004, the organization United for Peace and Justice wanted to hold a rally on the Great Lawn during the Republican National Convention. The city denied application for a permit, stating that such a mass gathering would be harmful to the grass and that such damage would make it harder to collect private donations to maintain the park. Courts upheld the refusal.

Since the 1960s, there has been a grassroots campaign to restore the park's loop drives to their original car-free state. Over the years, the number of car-free hours[36] has increased, though a full closure is currently resisted by the New York City Department of Transportation.

The Central Park Medical Unit is an all-volunteer ambulance service that provides free emergency medical service to patrons of Central Park and the surrounding streets. It operates a rapid-response bicycle patrol, particularly during major events such as the New York City Marathon, the 1998 Goodwill Games, and concerts in the park.

Central Park has one of the largest remaining stands of American Elms in the northeastern U.S., 1,700 of them, protected by their isolation from Dutch Elm Disease. Central Park was the site of the unfortunate unleashing of starlings in North America, which are considered an invasive species. Central Park is a popular birding spot during spring and fall migration, when birds flying over Manhattan are attracted to the prominent oasis. Over a quarter of all the bird species found in the United States have been seen in Central Park. A Red-tailed hawk known as Pale Male was the object of much attention by the media, the ornithologist-author Marie Winn and other Central Park birdwatchers. There are 215 bird species in New York City's Central Park.[37]

In 2002 a new genus and species of centipede was discovered in Central Park. The centipede is about four-tenths of an inch (10 mm) long, making it one of the smallest in the world. It is named Nannarrup hoffmani (after the man who discovered it) and lives in the park's leaf litter, the crumbling organic debris that accumulates under the trees.

Since the late 1990s, the Central Park Conservancy, the United States Department of Agriculture, and several city and state agencies have been fighting an infestation of the Asian long-horned beetle, which has been reported in Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan, including some parts of Central Park. The beetle, which likely was accidentally shipped from its native China in an untreated shipping crate, has no natural predators in the United States, and the fight to contain its infestation has been very expensive. The beetle infests trees by boring a hole in them to deposit its eggs, at which point the only way to end the infestation is to destroy the tree.

Central Park constitutes its own United States census tract, number 143. According to Census 2000, the park's population is eighteen people, twelve male and six female, with a median age of 38.5 years, and a household size of 2.33, over 3 households.[38]

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ^ a b c About the Central Park Conservancy, Central Park Conservancy. Accessed October 8, 2007.

- ^ "America's Most Visited City Parks" (PDF). The Trust for Public Land. 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Central Park". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-10.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory" (PDF). National Park Service. 1975-08-14.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory" (PDF). National Park Service. 1975-08-14.

- ^ all the present bodies of water in the park have been created by damming natural seeps and flows.

- ^ Rebekah Kreshkoff and Marie Winn, The Birds of Central Park: An Annotated Checklist (on-line text).,

- ^ Robledo, S. Jhoanna; "Central Park: Because We Wouldn't Trade a Patch of Grass for $528,783,552,000" NYMag.com, December 18, 2005 (Retrieved: 26 August 2009)

- ^ John Emerson Todd, Frederick Law Olmsted (Boston: Twayne Publishers: Twayne’s World Leader Series) 1982:73; see the history of Green-Wood Cemetery.

- ^ Henry Hope Reed, Robert M. McGee and Esther Mipaas. The Bridges of Central Park. (Greensward Foundation) 1990.

- ^ Central Park's history 1800-1858

- ^ Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: a history of Central Park, 1992:150.

- ^ pbs.org – New York: A Documentary Film

- ^ Blonsky, Douglas. "Saving the Park: a key to NYC's revival". The New York Post, 3 November 2007 Op-Ed page.

- ^ Blonsky 2007 op. cit.

- ^ In 2007 3000 volunteers outnumbered under 250 workers over 12-to-1 (Blonsky 2007, op.cit.).

- ^ Blonsky 2007, op.cit..

- ^ a b Tradition or Cruelty?, Jessica Bennett, Newsweek, September 25, 2007; accessed August 23, 2008

- ^ Chris Hicks (April 16, 1996). "Jupiter's Wife". Deseret News. Salt Lake City.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bill Could Halt New York Carriage Horses, Keith B. Richburg, The Washington Post, December 17, 2007; accessed August 23, 2008

- ^ Another Horse Down in Central Park, Blog of the ASPCA, September 17, 2007; accessed August 23, 2008.

- ^ PETA Fact Sheet on Horse Carriage; accessed August 23, 2008

- ^ Home on the Asphalt, Lloyd Grove, New York Magazine, March 16, 2008; accessed August 23, 2008

- ^ a b Carriage Horse Industry At A Crossroads, Kristin Cole, CBS News, November 5, 2007; Accessed August 23, 2008.

- ^ Horse Pucky, Editorial of The New York Sun, November 30, 2007; accessed August 23, 2008

- ^ Film Highlights Suffering of NYC Carriage Horses, Humane Society of the United States, April 24, 2008

- ^ "In recent years, pedicabs have become ubiquitous in Midtown. They pick up theatergoers on Broadway, courting couples in Central Park and give gawking tourists a new way to stare at the tall buildings" ("Keep the Big Wheels Turning ", The New York Times, 18 December 2005).

- ^ For the Bon Jovi concert, 12 July 2008, 60,000 free tickets were distributed by the city; a large section of Central Park was closed to the non-ticketed public.

- ^ Official Garth Brooks website: "In May of 1998, the Fire Department of the City of New York officially announced the final attendee numbers at 980,000." (accessed 14 February 2010).

- ^ Christopher S. Wren, "A Summit in Central Park; Boulder Gives Climbers a Taste of the Mountain", The New York Times, July 21, 1999. Accessed October 8, 2007.

- ^ CityListen Audio Tours, Central Park: An Urban Marvel

- ^ February 25, 2005 CNN story about Christo and Jeanne-Claude's The Gates Central Park's 'Gates' to close

- ^ CourtTv.com

- ^ New York Lawyer

- ^ Curfew Hours in Central Park

- ^ New York City Economic Development Corporation

- ^ "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2006-07-11.

References

- Kelly, Bruce, Gail T. Guillet, and Mary Ellen W. Hern. Art of the Olmsted Landscape. New York: City Landmarks Preservation Commission: Arts Publisher, 1981. ISBN 0-941302-00-8.

- Kinkead, Eugene. Central Park, 1857-1995: The Birth, Decline, and Renewal of a National Treasure. New York: Norton, 1990. ISBN 0-393-02531-4.

- Miller, Sara Cedar. Central Park, An American Masterpiece: A Comprehensive History of the Nation's First Urban Park. New York: Abrams, 2003. ISBN 0-8109-3946-0.

- Rosenzweig, Roy, and Elizabeth Blackmar. The Park and the People: A History of Central Park. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8014-9751-5.

- Swerdlow, Joel L. Central Park - Oasis in the city. National Geographic Magazine May 1993

External links

- Official websites

- Additional information

- Central Park in New York

- CentralPark.com: The complete guide to Central Park

- CentralParkHistory.com: The complete history of Central Park

- Forgotten-NY: Secrets of Central Park

- National Historic Landmarks Program: Central Park

- NYCtrl.com: Central Park Reservoir Project

- Elisabeth Barlow Rogers: The Central Park Story. Management and Restoration for a New Era of Public Use

- Central Park