Rashomon

This article contains too many pictures for its overall length. (January 2010) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2010) |

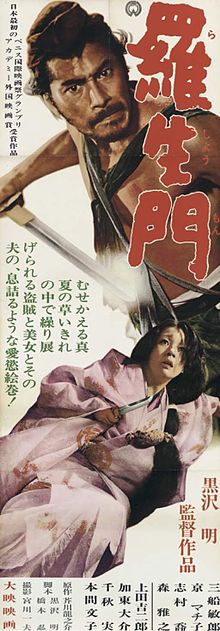

| Rashomon | |

|---|---|

Japanese original poster | |

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Written by | Short stories: Ryūnosuke Akutagawa Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto |

| Produced by | Minoru Jingo |

| Starring | Toshirō Mifune, Masayuki Mori, Machiko Kyō, Takashi Shimura, Minoru Chiaki |

| Cinematography | Kazuo Miyagawa |

| Edited by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Music by | Fumio Hayasaka |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Japan: Daiei United States: RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates | Japan: August 25, 1950 United States: December 26, 1951 |

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | $250,000 |

Rashomon (羅生門, Rashōmon) is a 1950 Japanese crime mystery film directed by Akira Kurosawa, working in close collaboration with cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa. It stars Toshirō Mifune, Masayuki Mori, Machiko Kyō and Takashi Shimura. The film is based on two stories by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa — ("Rashomon" provides the setting, while "In a Grove" provides the characters and plot).

Rashomon can be said to have introduced Kurosawa and Japanese cinema to Western audiences, albeit to a small and discerning number of theatres, and is considered one of his masterpieces. The film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and also received an Academy Honorary Award at the 24th Academy Awards.

Synopsis

The film depicts the rape of a woman and the murder of her samurai husband, through the widely differing accounts of four witnesses, including the bandit/rapist, the wife, the dead man speaking through a medium (Fumiko Honma), and lastly the narrator, the one witness that seems the most objective and least biased. While the stories are mutually contradictory only the final version is unmotivated by other factors. Accepting the final version as the truth (the now common technique of film and TV of only explaining the truth last was not a universal approach at that time) explains why in each other version "the truth" was worse than admitting to the killing, and it is precisely this assessment which gives the film its power, and this theme which is echoed in other works.

The story unfolds in flashback as the four characters—the bandit Tajōmaru (Toshirō Mifune), the samurai's wife (Machiko Kyō), the murdered samurai (Masayuki Mori), and the nameless woodcutter (Takashi Shimura)—recount the events of one afternoon in a grove. The first three versions are told by the priest (Minoru Chiaki), who was present at the trial as a witness, having bumped into the couple on the road just prior to the events. Each of these versions has a response of "lies" from the woodcutter. The final version comes direct from the woodcutter, as the only witness (but he did not admit this to the court). All versions are told to a ribald commoner (Kichijiro Ueda) as they wait out a rainstorm in a ruined gatehouse identified by a sign as Rashōmon.

Plot

The film opens on a woodcutter (木樵り; Kikori) and a priest (旅法師; Tabi Hōshi) sitting beneath Rashōmon gate to stay dry in a downpour. A commoner joins them and they tell him that they've witnessed a disturbing story, which they then begin recounting to him. The woodcutter claims he found the body of a murdered samurai three days earlier while looking for wood in the forest; upon discovering the body, he says, he fled in a panic to notify the authorities. The priest says that he saw the samurai and the woman traveling the same day the murder happened. Both men were then summoned to testify in court, where they met the captured bandit Tajōmaru (多襄丸), who claimed responsibility for the rape and murder.

- The bandit's story

Tajōmaru, a notorious brigand (盗人; nusubito), claims that he tricked the samurai to step off the mountain trail with him and look at a cache of ancient swords he discovered. In the grove he tied the samurai to a tree, then brought the woman there. She initially tried to defend herself with a dagger, but was eventually "seduced" by the bandit. The woman, filled with shame, then begged him to duel to the death with her husband, to save her from the guilt and shame of having two men know her dishonor. Tajōmaru honorably set the samurai free and dueled with him. In Tajōmaru's recollection they fought skillfully and fiercely, but in the end Tajōmaru was the victor and the woman ran away. At the end of the story to the court, he is asked about an expensive dagger owned by the samurai's wife: he says that, in the confusion, he forgot all about it, and that it was foolish of him to leave behind such a valuable object.

- The wife's story

The samurai's wife tells a different story to the court. She says that Tajōmaru left after raping her. She begged her husband to forgive her, but he simply looked at her coldly. She then freed him and begged him to kill her so that she would be at peace. He continued to stare at her with a look of loathing. His expression disturbed her so much that she fainted with dagger in hand. She awoke to find her husband dead with the dagger in his chest. She attempted to kill herself, but failed in all her efforts.

- The samurai's story

The court then hears the story of the deceased samurai, told through a medium (巫女; miko). The samurai claims that Tajōmaru, after raping his wife, asked her to travel with him. She accepted and asked Tajōmaru to kill her husband so that she would not feel the guilt of belonging to two men. Tajōmaru, shocked by this request, grabbed her, and gave the samurai a choice of letting the woman go or killing her. ("For these words alone," the dead samurai recounted, "I was ready to pardon his crime.") The woman fled, and Tajōmaru, after attempting to recapture her, gave up and set the samurai free. The samurai then killed himself with his own dagger; later, somebody removed the dagger from his chest.

- The woodcutter's story

Back at Rashōmon gate (after the trial), the woodcutter explains to the commoner that the samurai's story was a lie. The woodcutter had actually witnessed the rape and murder, he says, but just did not want to get too involved at the trial. According to the woodcutter's new story, Tajōmaru begged the samurai's wife to marry him, but the woman instead freed her husband. The husband was initially unwilling to fight Tajōmaru, saying he would not risk his life for a spoiled woman, but the woman then criticized both him and Tajōmaru, saying they were not real men and that a real man would fight for a woman's love. She spurred the men to fight one another, but then hid her face in fear once they raise swords; the men, too, were visibly fearful as they begin fighting. They began a duel that was much more pitiful than Tajōmaru's account had made it sound, and Tajōmaru ultimately won through a stroke of luck. After some hesitation he killed the samurai, and the woman fled in horror. Tajōmaru could not catch her, but took the samurai's sword and left the scene limping.

- Climax

At the temple, the woodcutter, priest, and commoner are interrupted from their discussion of the woodcutter's account by the sound of a crying baby. They find the baby abandoned in a basket, and the commoner takes a kimono and an amulet that have been left for the baby. The woodcutter reproaches the commoner for stealing from the abandoned baby, but the commoner chastises him. Having deduced that the woodcutter in fact stole the dagger from the scene of the murder, the commoner mocks him, "a bandit calling another a bandit". The commoner leaves Rashōmon, claiming that all men are motivated only by self-interest.

These deceptions and lies shake the priest's faith in humanity. He is brought back to his senses when the woodcutter reaches for the baby in the priest's arms. The priest is suspicious at first, but the woodcutter explains that he intends to take care of the baby along with his own children, of whom he already has six. This simple revelation recasts the woodcutter's story and the subsequent theft of the dagger in a new light. The priest gives the baby to the woodcutter, saying that the woodcutter has given him reason to continue having hope in humanity. The film closes on the woodcutter, walking home with the baby. The rain has stopped and the clouds have opened revealing the sun in contrast to the beginning where it was overcast.

Motivations

If we accept the last version to be true we can assess what motivated each different story version of events. The truth appears to be a sorry but realistic state of affairs, filled with shame and cowardice. It must be remembered that all parties were present and all know the true sequence of events. There is therefore motivation behind each response.

In the bandit's version he accepts blame, but makes the fight appear an honorable and heroic duel. He therefore retains his reputation as a fierce and manly warrior.

In the wife's version, given that she was in fact responsible for inciting the duel, she intentionally cast herself as a victim by testifying that she had insisted on an honorable death, only to end up killing her husband. Thus, she preserves her modesty and innocence in the eyes of society.

The medium's version requires two interpretations: one if you accept that spirits can speak through a medium; a second if you presume it is the medium themselves giving this interpretation of events. If seen from the viewpoint of the now dead samurai, he has reason to be ashamed. Taking full blame for his own death, lets the bandit off the hook, and given that his wife was largely to blame for the duel this is perhaps a fair approach. If we presume this version to be the invention of the medium, this interpretation has a slightly different slant (because they do not know the true events). In this case, assembling information from the other witnesses paints a broad picture. Choosing a suicide option lays less blame on the two survivors and can be seen as a damage-limitation exercise.

However, the overall issue here is that one can be on morally higher ground by admitting to a murder than admitting to other actual actions, and this is the crux of the film.

Style

Influence of silent film and modern art

Kurosawa's admiration for silent film and modern art can be seen in the film's minimalist sets. Kurosawa felt that sound cinema multiplies the complexity of a film: "Cinematic sound is never merely accompaniment, never merely what the sound machine caught while you took the scene. Real sound does not merely add to the images, it multiplies it." Regarding Rashomon, Kurosawa said, "I like silent pictures and I always have ... I wanted to restore some of this beauty. I thought of it, I remember in this way: one of techniques of modern art is simplification, and that I must therefore simplify this film."[1]

Accordingly, there are only three settings in the film: Rashōmon gate, the woods and the courtyard. The gate and the courtyard are very simply constructed and the woodland is real. This is partly due to the low budget that Kurosawa got from Daiei.

Kurosawa's relationship with the cast

When Kurosawa shot Rashomon, the actors and the staff lived together, a system Kurosawa found beneficial. He recalls "We were a very small group and it was as though I was directing Rashomon every minute of the day and night. At times like this, you can talk everything over and get very close indeed".[2]

Cinematography

The cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa, contributed an enormous amount of ideas and support. For example, in one sequence, there is a series of single close-ups of the bandit, then the wife, and then the husband, which then repeats to emphasize the triangular relationship between them.

Use of contrasting shots is another example of techniques in Rashomon. According to Donald Richie, the length of time of the shots of the wife and of the bandit are the same when the bandit is barbarically crazy and the wife is hysterically crazy.[3]

Rashomon shot directly into the sun. In the shots of the actors, Kurosawa wanted to use natural light, but it was too weak; they solved the problem by using a mirror to reflect the natural light. The result is to make the strong sunlight look as though it has traveled through the branches, hitting the actors. The rain in the film had to be tinted with black ink because camera lenses could not capture rain made with pure water.

Symbolic use of Light

Robert Altman marvels at the use of light in the film. He compliments Kurosawa's use of "dappled" light throughout the film, which gives the characters and settings further ambiguity.[4] In his essay "Rashomon", Tadao Sato suggests that the film (unusually) uses sunlight to symbolize evil and sin in the film, arguing that the wife gives in to the bandit's desires when she sees the sun. However, writer Keiko I. McDonald opposes Sato's idea in her essay "The Dialectic of Light and Darkness in Kurosawa’s Rashomon". McDonald says the film conventionally uses light to symbolize "good" or "reason" and darkness to symbolize "bad" or "impulse". She interprets the scene mentioned by Sato differently, pointing out that the wife gives herself to the bandit when the sun slowly fades out. McDonald also reveals that Kurosawa was waiting for a big cloud to appear over Rashomon gate to shoot the final scene in which the woodcutter takes the abandoned baby home; Kurosawa wanted to show that there might be another dark rain any time soon, even though the sky is clear at this moment. Unfortunately, the final scene appears optimistic because it was too sunny and clear to produce the effects of an overcast sky.

Editing

Stanley Kauffman writes in The Impact of Rashomon that Kurosawa often shot a scene with several cameras at the same time, so that he could "cut the film freely and splice together the pieces which have caught the action forcefully, as if flying from one piece to another." Despite this, he also used short shots edited together that trick the audience into seeing one shot; Richie says in his essay that "there are 407 separate shots in the body of the film ... This is more than twice the number in the usual film, and yet these shots never call attention to themselves".

Music

Hayasaka's film score included the application of "Boléro" by Maurice Ravel.[5][6]

Allegorical and Symbolic content

Due to its emphasis on the subjectivity of truth and the uncertainty of factual accuracy, Rashomon has been read by some as an allegory of the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II. James F. Davidson's article "Memory of Defeat in Japan: A Reappraisal of Rashomon" in the December 1954 issue of the Antioch Review, is an early analysis of the World War II defeat elements.[7]

Another allegorical interpretation of the film is mentioned briefly in a 1995 article "Japan: An Ambivalent Nation, an Ambivalent Cinema" by David M. Desser.[8] Here, the film is seen as an allegory of the atomic bomb and Japanese defeat. It also briefly mentions James Goodwin's view on the influence of post-war events on the film.

However, Akutagawa's "In a Grove" predates Kurosawa's film adaptation by 28 years, thus any intentional postwar allegory would have been the result of Kurosawa's editing (based more on the framing of the tale than the events themselves).

Symbolism runs rampant throughout the film and much has been written on the subject. Bucking tradition, Miyagawa directly filmed the sun through the leaves of the trees, as if to show the light of truth becoming obscured. The gatehouse that we continually return to as the 'home' location for the storytelling serves as a visual metaphor for a gateway into the story, and the fact that the three men at the gate gradually tear it down and burn it as the stories are told is a further comment on the nature of the truth of what they are telling.

Impact and Influence

Japanese responses

The film was produced by Daiei. When it received positive responses in the West, Japanese critics were baffled; some decided that it was only admired there because it was "exotic," others thought that it succeeded because it was more "Western" than most Japanese films.[9]

In a collection of interpretations of Rashomon, Donald Richie writes that "the confines of 'Japanese' thought could not contain the director, who thereby joined the world at large".[10] He also quotes Kurosawa criticizing the way the "Japanese think too little of our own [Japanese] things".

Influence outside Japan

The film appeared at the 1951 Venice Film Festival at the behest of an Italian language teacher, Giuliana Stramigioli who had recommended it to Italian film promotion agency Unitalia Film seeking a Japanese film to screen at the festival. However, Daiei Motion Picture Company (a producer of popular features at the time) and the Japanese government had disagreed with the choice of Kurosawa's work on the grounds that it was "not [representative enough] of the Japanese movie industry" and felt that a work of Yasujiro Ozu would have been more illustrative of excellence in Japanese cinema. Despite these reservations, the film was screened at the festival and won both the Italian Critics Award and the Golden Lion award—introducing western audiences, including western directors, more noticeably to both Kurosawa's films and techniques, such as shooting directly into the sun and using mirrors to reflect sunlight onto the actor's faces.

The 1964 Western The Outrage, which starred Paul Newman, Claire Bloom, Edward G. Robinson, and William Shatner, was a remake of Rashomon, with Kurosawa acknowledged for the screenplay.

The film's concept has influenced a variety of subsequent films, such as Hero, Vantage Point, Courage Under Fire, Basic and One Night at McCool's.

The multiple-perspective concept has also been used, sometimes with over-the-top exaggeration for comedic expression, in episodes of many television programs. The American sitcom All in the Family contains an episode "Everybody Tells the Truth", wherein characters Archie Bunker and Mike Stivic give conflicting accounts of an incident involving a refrigerator repairman and a black apprentice repairman. An episode from Mama's Family titled "Rashomama" where Eunice, Ellen, and Naomi tell overly exaggerated versions of how Mama got hit in the head with the pot while making gooseberry jam. "I Witness", the fourth-season finale of Magnum, P.I., features a robbery of the King Kamehameha Club in which the three main supporting characters of the series (Higgins, Rick, and T.C.) are victimized and relate widely-varying, self-serving statements to investigator Tanaka. An episode of the animated series King of the Hill features the main characters recounting events that led to a fire station burning down while acting as volunteer firefighters, with each character's story making themselves out to be heroic while the others are bumbling. An episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation titled "A Matter of Perspective" features a very similar story in which a character is accused of murdering a scientist because of an alleged interest in the scientist's wife, and several similar but contradictory scenarios based on the testimony of the people involved are played out on the holodeck. In the Leverage episode "The Rashomon Job", team members recount contradictory stories about a night five years earlier, when it turns out they each unwittingly tried to steal the same artifact at the same time.

The first act of Michael John LaChiusa's musical, See What I Wanna See, is also based on the same short stories by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, and features a main character who goes to a theater to see Rashomon. In an episode of Fame based on the movie, the Rashomon Gate setting is replaced by a theater marquee, under which two characters huddle to wait out a rainstorm; only after the entire story has unfolded in flashback does the camera pan back enough to disclose that the theater marquee announces "A Kurosawa Festival".

Influence on philosophy

- Rashomon plays a central role in Martin Heidegger's dialogue between a Japanese person and an inquirer. Where the inquirer praises the film early on for being a way into the "mysterious" Japanese world, the Japanese person condemns the film for being too European and dependent on a certain objectifying realism not present in traditional Japanese noh plays.[11]

- The political scientist Graham Allison claimed to have used Rashomon as a starting point for his magnum opus, Essence of Decision, in which he told the story of the Cuban Missile Crisis from three different theoretical viewpoints (and, as a result, the Crisis is described and explained in three entirely different ways).

Awards

- Blue Ribbon Awards (1951) - Best Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa and Shinobu Hashimoto

- Mainichi Film Concours (1951) - Best Actress: Machiko Kyō

- Venice Film Festival (1951) - Golden Lion: Akira Kurosawa

- National Board of Review USA (1951) - Best Director: Akira Kurosawa and Best Foreign Film: Japan

- 24th Academy Awards, USA (1952) - Honorary Academy Award

Top lists

The film appeared on many critics' top lists of the best films.

- 5th - Top ten list in 1950, Kinema Junpo

- 10th - Directors' Top Ten Poll in 1992, Sight & Sound

- 9th - Directors' Top Ten Poll in 2002, Sight & Sound

- 290th - The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time in 2008, Empire[12]

- 50 Klassiker, Film by Nicolaus Schröder in 2002[13]

- 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die by Steven Jay Schneider in 2003[14]

- Ranked #22 in Empire magazines "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[15]

See also

- The Outrage (1964 remake)

- Hero (2002 film)

- Courage Under Fire (1996)

- See What I Wanna See (Michael John LaChiusa musical)

- Basic (2003)

- Virumaandi (2004)

- Vantage Point (2008)

References

- ^ Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa.

- ^ Qtd. in Richie, Films.

- ^ Richie, Films.

- ^ Altman, Robert. "Altman Introduction to Rashomon", Criterion Collection DVD, Rashomon.

- ^ http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3406802357.html

- ^ http://www.cinemathequeontario.ca/filmdetail.aspx?filmId=82&archives=1&season=Summer2006&page=2

- ^ The article has since appeared in some subsequent Rashomon anthologies, including Focus on Rashomon [1] in 1972 and Rashomon (Rutgers Film in Print) [2] in 1987. Davidson's article is referred to in other sources, in support of various ideas. These sources include: The Fifty-Year War: Rashomon, After Life, and Japanese Film Narratives of Remembering a 2003 article by Mike Sugimoto in Japan Studies Review Volume 7 [3], Japanese Cinema: Kurosawa's Ronin by G. Sham [4], Critical Reception of Rashomon in the West by Greg M. Smith, Asian Cinema 13.2 (Fall/Winter 2002) 115-28 [5], Rashomon vs. Optimistic Rationalism Concerning the Existence of "True Facts" [6], Persistent Ambiguity and Moral Responsibility in Rashomon by Robert van Es [7] and Judgment by Film: Socio-Legal Functions of Rashomon by Orit Kamir [8].

- ^ Hiroshima in Film

- ^ Rashomon

- ^ (Richie, 80)

- ^ Martin Heidegger, "Aus einem Gespräch von der Sprache. Zwischen einem Japaner und einem Fragenden", in Unterwegs zur Sprache, Neske, 1959, p. 104ss.

- ^ http://www.empireonline.com/500

- ^ Schröder, Nicolaus. (2002). 50 Klassiker, Film. Gerstenberg. ISBN 9783806725094.

- ^ http://1001beforeyoudie.com

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Empire.

{{cite web}}: Text "22. Rashomon" ignored (help)

Further reading

- Davidson, James F. "Memory of Defeat in Japan: A Reappraisal of Rashomon". Rashomon. Ed. Donald Richie. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1987. page 159-166.

- Erens, Patricia. Akira Kurosawa: a guide to references and resources. Boston: G.K.Hall, 1979.

- Kauffman, Stanley. "The Impact of Rashomon". Rashomon. Ed. Donald Richie. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1987. page 173-177.

- McDonald, Keiko I. "The Dialectic of Light and Darkness in Kurosawa's Rashomon". Rashomon. Ed. Donald Richie. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1987. page 183-192.

- Richie, Donald. "Rashomon". Rashomon. Ed. Donald Richie. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1987. page 1-21.

- Richie, Donald. The Films of Akira Kurosawa. 2nd ed. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California P, 1984.

- Sato, Tadao. "Rashomon". Rashomon. Ed. Donald Richie. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1987. page 167-172.

- Tyler, Parker. "Rashomon as Modern Art". Rashomon. Ed. Donald Richie. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1987. page 149-158.