Mexican Revolution

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2010) |

| Mexican Revolution Revolución Mexicana | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Madero revolution (Federal Troops led by Porfirio Díaz) |

Madero revolution Maderistas Orozquistas Villistas Zapatistas |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Madero revolution |

Madero revolution Francisco I. Madero Pascual Orozco Francisco Villa Emiliano Zapata | |||||||

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Mexican Revolution (Spanish: Revolución mexicana) was a major armed struggle that started in 1910, with an uprising led by Francisco I. Madero against longtime autocrat Porfirio Díaz. The Revolution was characterized by several socialist, liberal, anarchist, populist, and agrarianist movements. Over time the Revolution changed from a revolt against the established order to a multi-sided civil war.

After prolonged struggles, a and deep sexual erges, its representatives produced the Mexican Constitution of 1917. The Revolution is generally considered to have lasted until 1920, although the country continued to have sporadic, but comparatively minor, outbreaks of warfare well into the 1920s. The Cristero War of 1926 to 1929 was the most significant relapse of bloodshed.

The Revolution triggered the creation of the National Revolutionary Party in 1929 (renamed the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, in 1946). Under a variety of leaders, the PRI held power until the general election of 2000.

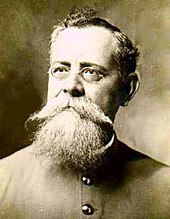

Porfirio Díaz's rule (DLCC)

After Benito Juárez's death in 1872, Porfirio Díaz wanted to take over as Mexico's leader. As allies the two men had fought against the French in the Battle of Puebla, but once Juárez rose to power Díaz tried to unseat him. Díaz began his reign as president in 1876, and ruled until May 1911 [1] when Francisco I. Madero succeeded him, taking office in November 1911.[2] Díaz's regime is remembered for the advances he brought in industry and modernization, at the expense of human rights and liberal reforms. He worked to reduce the power of the Roman Catholic Church and expropriated some of their large property holdings.

Porfirio Díaz's government from 1876–1910 has become known as the Porfiriato. Díaz had a strict "No Re-election" policy in which presidents could not serve consecutive terms in office. He followed this rule when he stepped down (1880) after his first term and was succeeded by Manuel González. The new president's period in office was marked by political corruption and official incompetence. When Díaz ran in the next election (1884), he was a welcome replacement. In future elections Díaz would conveniently put aside his "No Re-election" slogan and ran for president in every election.

Díaz became the dictator he had warned the people against. Through the army, the Rurales, and gangs of thugs, Diaz frightened people into voting for him. When bullying citizens into voting for him failed, he simply rigged the votes in his favor.[3] Díaz knew he was violating the constitution by using force to stay in office. He justified his acts by claiming that Mexico was not yet ready to govern itself;[citation needed] only he knew what was best for his country and he enforced his belief with a strong hand. "Order followed by Progress" were the watchwords of his rule.[citation needed]

While Díaz's presidency was characterized by promotion of industry and the pacification of the country, some said it came at the expense of the working class. Farmers and peasants both claimed to have suffered exploitation. The economy took a great leap during the Porfiriato, with his encouraging the construction of factories, roads, dams, industries and better farms. This resulted in the rise of an urban proletariat and the influx of foreign capital (principally from the United States).

Part of his success in maintaining power came from mitigating U.S. influence through European investments - primarily from Great Britain and Imperial Germany. Progress came at a price however, as basic rights such as freedom of the press were suspended under the Porfiriato.[4] The growing influence of the U.S. was a constant problem for Díaz. A major portion of Mexico's land (territory now known as the Mexican Cession) had earlier been ceded to the U.S.; both in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War, and the subsequent purchase of another large region by the United States in the Gadsden Purchase.

Wealth, political power and access to education were concentrated among a handful of families, overwhelmingly of European descent, who controlled much property in large estates. Most of the people in Mexico were landless. Foreign companies, mostly from the United Kingdom, France and the U.S., also exercised power in Mexico.

Díaz changed land reform efforts that were begun under previous leaders. Díaz's new land laws virtually undid all the hard work by leaders such as Juárez. No peasant or farmer could claim the land he occupied without formal legal title. Helpless and angry small farmers felt a change of regime would be necessary if Mexico was to continue being successful. For this reason, many leaders including Francisco I. Madero, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata would launch a rebellion against Díaz, escalating into the eventual Mexican Revolution. When it came to the land reform 95% of Mexico's land was owned by only 5% of the Mexican population. This unfair distribution of land went on for years and angered many of the lower class. This corrupt system only allowed the rich to get richer and the poor to get poorer. Many of the workers on these Hacienda farms where beaten like slaves and were constantly being put into debt from their previous generations. Portiriato allowed this corrupt behavior to go on his entire time as he stayed in power.

Most historians mark the end of the Porfiriato in 1911 as the beginning of the Mexican Revolution. In a 1908 interview with the U.S. journalist James Creelman, Díaz stated that Mexico was ready for democracy and elections and that he would step down to allow other candidates to compete for the presidency.[5][6][7] Growing "old and careless", Díaz figured he would retire to Europe and allow a younger man to take over his presidency. Because of the dissidence this caused, Díaz decided to run again in 1910 for the last time, with an eye toward arranging a succession in the middle of his term.

Madero ran against Díaz in 1910. Diaz thought he could control this election as he had the previous seven.[8] Although similar overall to Díaz in his ideology,[citation needed] Madero hoped for other elites to rule alongside the president. Díaz did not approve of Madero and had him jailed on election day in 1910. Díaz was announced the winner of the election by a landslide, providing the initial impetus for the outbreak of the Revolution.

Francisco I. Madero's presidency (1911–1913)

Francisco I. Madero, a young man from a wealthy family in the northern state of Coahuila, stated in 1910 that he would be running in the next election against Díaz for the presidency. In order to ensure that Madero did not win, Díaz had Madero thrown in jail and then declared himself the winner. Madero soon escaped and fled for a short period of time to San Antonio, Texas, United States. On October 5, 1910, Madero issued a "letter from jail" called the Plan de San Luis Potosí, with its main slogan "free suffrage and no re-election." It declared the Díaz regime illegal and called for revolt against Díaz to overthrow the Porfiriato, starting on November 20. Though Madero's letter was not a plan for major socioeconomic revolution, it offered the hope of change for many disadvantaged Mexicans.[8]

Madero's vague promises of agrarian reforms attracted many of the peasants throughout Mexico. He gained support from them that he needed to remove Díaz from power. With the support of the mostly peasant Indians, Madero's army fought Díaz's army and had some success. Díaz's army gradually lost control of Mexico and his administration started to fall apart. The desire to remove Díaz was so great that many natives and different leaders supported Madero and fought on his side.

In late 1910, revolutionary movements broke out in response to Madero's letter. Pascual Orozco along with governor Abraham González formed a powerful military union in the north and took Mexicali and Chihuahua City, although they were not especially committed to Madero. These victories encouraged other military and political alliances, including Pancho Villa. Against Madero's wishes, Orozco and Villa fought for and won Ciudad Juárez, bordering El Paso, Texas, along the Rio Grande.

After Madero defeated the weak federal army, on May 21, 1911, he signed the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez with Diaz. It stated that Díaz would abdicate his rule and be replaced by Madero. Insisting on a new election, Madero won overwhelmingly in late 1911. Some supporters criticized him for appearing weak by not assuming the presidency and failing to pass immediate reforms. But Madero established a liberal democracy and received support from the United States and popular leaders such as Orozco, Villa, and Zapata.

Madero was a weak leader and quickly lost much of his support while in power. He angered both the more radical revolutionists and the conservative counter-revolutionists, including the unpopular Congress elected during Díaz's rule. His refusal to enact land reforms caused a break with Zapata who announced the Plan de Ayala, which called for the return of lands "usurped by the hacendados" (hacienda owners) and demanded an armed conflict against the government.

Soon after, Orozco also broke away from Madero's government and rebelled against him. He created his own army of Orozquistas, who were also called the Colorados ("Red Flaggers") after Madero refused to agree to social reforms calling for better working hours, pay, and conditions. The rural working class, who had supported Madero, now took up arms supporting Zapata and Orozco. The people's support for Madero quickly deteriorated.

Madero's time as leader was short lived and came to an end after General Victoriano Huerta set in motion a coup d'état. [citation needed] Madero had appointed Huerta as commander-in-chief when he first claimed power, but Huerta had turned against him. Following Huerta's coup d'état, Madero was forced to resign in 1913. Madero and vice president José María Pino Suárez were both assassinated less than a week later. The murder of Madero ruptured the country, but he became honored as a martyr of the revolution.

Victoriano Huerta's reign (1913–1914)

In early 1913, Victoriano Huerta, who commanded the armed forces, conspired with U.S. Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, Félix Díaz and Bernardo Reyes, to remove Madero from power. La decena trágica was an event in which ten days of sporadic fighting in a faked battle occurred between federal troops led by Huerta and Díaz's conservative rebel forces. This fighting would stop when Huerta, Félix Díaz, and Henry Lane Wilson met and signed the "Embassy Pact" in which they agreed to conspire against Madero to install Huerta as president.

When Huerta gained power and became president, most powers around the world acknowledged him as the rightful leader. However, incoming president of the United States Woodrow Wilson refused to recognize Huerta's government. Henry Lane Wilson was withdrawn as U.S. Ambassador by Woodrow Wilson and his Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, to be replaced by John Lind, a Swedish-American. Bryan, President Wilson, and many Mexicans saw Huerta as an illegal usurper of presidential power in violation of the Constitution of Mexico.

Venustiano Carranza, a politician and rancher from Coahuila, was forefront in the opposition against Huerta, calling his forces the Constitutionalists, with the secret support of the United States. On March 26, 1913, Carranza issued the Plan de Guadalupe, which was a refusal to recognize Huerta as president and called for a declaration of war between the two factions. Leaders such as Villa, Zapata, Carranza, and Álvaro Obregón led the fighting against Huerta. In April 1914, U.S. opposition to Huerta had reached its peak when American forces seized and occupied the port of Veracruz, cutting off arms and money supplies from Germany. In late July, this situation worsened for Huerta. He vacated his office and fled to Puerto México.

Legacy

After Huerta vacated the presidency, he moved to Spain in an attempt to establish a new home. Later he returned to Mexico to try to establish another counter-revolution within the post-revolutionary Mexican state.

Germany, which favored Huerta while in power, considered him an important factor related to the war breaking out in Europe (World War I). If Huerta could establish himself again as leader of Mexico, which was the German government's goal, the United States would be distracted on its homefront, giving the Germans an advantage in Europe. Huerta moved to the United States where he began to work toward another revolution in Mexico. The German government gave him funding and advice.

The U.S government and Carranza, the newly elected President of Mexico, were worried when Huerta arrived. They set up surveillance to watch Huerta and try to ensure he did not gain entry into Mexico. The United States government and Carranza wanted to prevent another counter-revolution.

Huerta did not survive long enough to re-enter into Mexico. He was stopped at the border in El Paso, Texas, by the United States government and kept there under house arrest. He died in early 1916.

Pancho Villa (active 1911–1916)

José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, better known as Francisco "Pancho" Villa, came from the northern state of Durango. Villa with his army of Villistas joined the ranks of the Madero movements. He led the Villistas in many battles, such as the attack of Ciudad Juárez in 1911 (which overthrew Porfirio Díaz and gave Madero a little power).

In 1911, Victoriano Huerta appointed Villa his chief military commander. [citation needed] During this period Huerta and Villa became rivals. In 1912 when Villa's men seized a horse and Villa decided to keep it for himself, Huerta ordered Villa's execution for insubordination. Raúl Madero, brother of President Madero, intervened to save Villa's life. Jailed in Mexico City, Villa escaped to the United States. Soon after the assassination of President Madero, Villa returned with a group of companions to fight Huerta. By 1913 the group had become Villa's División del Norte (Northern Division). This army led by Villa had numerous American members. Villa and his army, along with Carranza and Obregón, joined in resistance to the Huerta dictatorship.

Villa and Carranza had different goals. Because Villa wanted to continue the revolution, he became an enemy of Carranza. After Carranza took control in 1914, Villa and other revolutionaries who opposed him met at what was called the Convention of Aguascalientes. The convention deposed Carranza in favor of Eulalio Gutiérrez. In the winter of 1914, Villa and Zapata's troops entered and occupied Mexico City. Villa's treatment of Gutiérrez and the citizenry outraged more moderate elements of the population, who forced Villa from the city in early 1915.

In 1915, Villa took part in two of the most important battles during the revolution, the two engagements in the Battle of Celaya, on April 6–7 and from April 13–15. Obregon defeated Villa in the Battle of Celaya, one of the bloodiest of the revolution. Carranza emerged as the winner of the war and seized power. A short time after, the United States recognized Carranza as president of Mexico. On March 9, 1916, Villa crossed the United States–Mexico border and raided Columbus, New Mexico to attempt revenge against the arms dealer who sold the ammunition used in the Battle of Celaya, which was useless for Villa's forces. During this attack, 18 Americans and 90 of Villa's men were killed.

Pressured by public opinion (mainly driven by Hearst Newspapers) to confront Mexican attacks, US President Wilson sent General John J. Pershing and around 5,000 U.S. troops on an unsuccessful pursuit to capture Villa.[9] It was known as the Punitive Expedition. After nearly a year of pursuing Villa, Pershing was called off and given command of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I. The American intervention had been limited to the western sierras of Chihuahua. It was the first time the American Army used airplanes on military operations. Unlike Zapata, Villa fought through the northern part of Mexico. With the Americans always on high pursuit of him, Villa always had the upper hand by knowing the rough terrain of the Sonoran Desert and the Sierra mountains. Villa and his revoulutionary fighters fought by using quick guerilla warfare tactics.

Regardless of the intervention, the loss of the Battle of Celaya meant the rise to power of Carranza and the Sonora generals.

In 1920, Obregón (one of the sonorenses) finally reached an agreement with Villa, who retired from the armed fighting. In 1923 Villa was assassinated by a group of seven riflemen while traveling in his car in Parral. It is presumed such assassination was ordered by Obregón, who feared a supposed bid for the presidency by Villa.

Venustiano Carranza (1914–1920)

Venustiano Carranza became president in 1914, after the overthrow of the Huerta government. He was driven out of Mexico City by Villa and Zapata in 1915, but later gained the support of the masses by the development of a program of social and agrarian reform. He was elected president in 1917. To try to restrain the revolutionary slaughter, Carranza formed the Constitutional Army to try to bring peace by adoption of the majority of rebel social demands into the new constitution. He reluctantly incorporated most of these demands into the new Constitution of 1917. The socialist constitution addressed foreign ownership of resources, an organized labor code, the role of the Roman Catholic Church in education, and land reform.

During his presidency he relied on his personal secretary and close aide, Hermila Galindo de Topete to rally and campaign support for him. Through her propaganda he was able to gain the support of women, workers and peasants. Carranza also supported his secretary by lobbying for women's equality. He helped change and reform the legal status of women in Mexico.[10]

Although his intentions were good, Carranza was not able to stay in power long enough to enforce many of the reforms in the Constitution of 1917. There was greater decentralization of power because of his weakness. He had appointed General Obregón as Minister of War and of the Navy. In 1920, Obregón with other leading generals Plutarco Elías Calles and Adolfo de la Huerta led a revolt against Carranza under the Plan of Agua Prieta. Their forces assassinated Carranza on May 21, 1920.[citation needed]

Emiliano Zapata (active 1910–1919)

Emiliano Zapata was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution. He is considered one of the outstanding national heroes of Mexico: towns, streets, and housing developments called "Emiliano Zapata" are common across the country. His image has been used on Mexican banknotes. People have long taken different sides on their evaluation of Emiliano Zapata and his followers. Some considered them bandits, but to others they were true revolutionaries who worked for the peasants. Presidents Porfirio Díaz and Venustiano Carranza called Zapata a womanizer, barbarian, terrorist, and a bandit. Conservative media nicknamed Zapata "The Attila of the South".

Many peasant and indigenous Mexicans admired Zapata as a practical revolutionary whose populist battle cry "Tierra y Libertad" (Land and Liberty) was elaborated in the Plan de Ayala for land reform. He fought for political and economic emancipation of the peasants in Southern Mexico. General Zapata's trademark saying was, "It's better to die on your feet than to live on your knees."[11] Zapata was killed in 1919 by General Pablo González and his aide Colonel Jesús Guajardo in an elaborate ambush. Guajardo set up the meeting under the pretext of wanting to defect to Zapata's side. At the meeting, Gonzalez's men assassinated Zapata.

Zapatistas

"Zapatista" originally referred to a member of the revolutionary guerrilla movement founded about 1910 by Zapata. His Liberation Army of the South (Ejército Libertador del Sur) fought during the Mexican Revolution for the redistribution of agricultural land. Zapata and his army and allies, including Pancho Villa, fought for agrarian reform in Mexico. Specifically they wanted to establish communal land rights for Mexico's indigenous population, which had mostly lost its land to the wealthy elite of European descent.

The majority of Zapata's supporters were indigenous peasants from Morelos and surrounding areas. But intellectuals from urban areas also joined the Zapatistas and played a significant part in their movement, specifically the structure and communication of the Zapatista ambitions. Zapata had received only a few years of limited education in Morelos. Educated supporters helped express his political aims. The urban intellectuals were known as "city boys" and were predominantly young males. They joined the Zapatistas for many reasons, including curiosity, sympathy, and ambition.

Zapata agreed that intellectuals could work on political strategy, but he had the chief role in proclaiming Zapatista ideology. The city boys also provided medical care, helped promote and instruct supporters in Zapatista ideology, created a plan for agrarian reform, aided in rebuilding villages destroyed by government forces, wrote manifestos, and sent messages from Zapata to other revolutionary leaders. Zapata's compadre Otilio Montaño was one of the most prominent city boys. Before the Revolution, Montaño was a professor. During the Revolution he taught Zapatismo, recruited citizens, and wrote the Plan de Ayala for land reform. Other well-known city boys were Abraham Martínez, Manuel Palafox, Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, Pablo Torres Burgos, Gildardo Magaña, Dolores Jiménez y Muro, Enrique Villa, and Genaro Amezcua.[12]

Zapatista women

Many women were involved with and supported the Zapatistas. Since Zapata's political ambitions and campaign were usually local, the women were able to aid the Zapatista soldiers from their homes. There were also female Zapatista soldiers who served from the beginning of the revolution. When Zapata met with President Madero on July 12, 1911, he was accompanied by his troops. Amongst these troops were female soldiers, including officers. Some women also led bandit gangs before and during the Revolution. Women joined the Zapatistas as soldiers for various reasons, including revenge for dead family members or to perform raids. Perhaps the most popular Zapatista female soldier was Margarita Neri, who was a commander. Women fought bravely as Zapatista soldiers and some were killed in battle. Many survivors continued to wear men's clothing and carry pistols long after the Revolution ended. Colonel María de la Luz Espinosa Barrera was one of the few whose service was formally recognized with a pension as a veteran of the Mexican Revolution.

Agrarian land reform

Under the Porfiriato, the rural peasants suffered the most. The regime confiscated large sections of land, which caused a major loss of land by the agrarian work force. In 1883 a land law was passed that gave ownership of more than 27.5 million hectares of land to foreign companies. By 1894, one out of every five acres of Mexican land was owned by a foreign interest. Many wealthy families also owned large estates, resulting in landless rural peasants working on the property as virtual slaves. In 1910 at the beginning of the revolution, about one half the rural population lived and worked on such plantations.

United States involvement

The United States was involved politically and socially with the Mexican revolution from 1910-1920. The United States had attitudes and interests among the Mexican population. The attitudes stem mostly from common American people including religious groups and women's groups. These organizations were socially involved with Mexico during the revolution because of the harsh times that many Mexican people faced economically and socially. The Mexican people were devastated by the revolution and had no work, adequate food or sheltering. The attitude of American organizations like the religious and women’s groups, was that they could not just let the Mexican people suffer, they had to help them. Numerous groups, such as the Red Cross, were able to help the Mexican people during the revolution. The interests among the United States citizens in Mexico during the revolution on the other hand were mostly representative of the United States politicians. The economic interest in Mexico during 1910-1920 had decided United States policy toward Mexico and thus the United States response and involvement with Mexico during this time.

At the turn of the 20th century, Americans, including major companies, held about 27 percent of Mexican land. By 1910 American industrial investment had increased even more, pushing Presidents William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson to intervene in Mexican affairs. For both economic and political reasons, the United States government generally supported whoever was in power, though President Wilson did condemn Huerta's murders of Madero and Pino Suárez. Twice during the Revolution, the United States sent troops into Mexico.

The first time was in 1914, during the Ypiranga incident. When United States agents discovered that the German merchant ship Ypiranga was carrying illegal arms to Huerta, President Wilson ordered troops to the port of Veracruz to stop the ship from docking. He did not declare war on Mexico. The United States troops then skirmished with Huerta's forces in Veracruz. The Ypiranga managed to dock at another port, which infuriated Wilson. The ABC Powers arbitrated and United States troops left Mexican soil, but the incident added to already tense United States–Mexico relations.

In 1916, in retaliation for Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico, and the death of 16 American citizens, President Wilson sent Brigadier General John J. Pershing into Mexico to capture Villa. Villa was deeply entrenched in the mountains of northern Mexico, and knew the terrain too well to be captured by the United States forces. General Pershing was forced to abandon the mission and return to the United States. This event, however, further damaged the strained United States–Mexico relationship and caused Mexico's anti-American sentiment to grow stronger. Some[who?] historians believed the United States government invested too much in the Mexican issue and violated its own avowed neutrality.

The Catholic Church during the revolution

During the period of 1876 to 1911, relations between the Roman Catholic Church and the Mexican government were stable. Porfirio Díaz had a keen interest in relations with the Church since he was worried about the American expansionist threat. Porfirio Díaz has been quoted as saying:

- "Persecution of the Church, whether or not the clergy enter into the matter, means war, and such a war that the Government can win it only against its own people, through the humiliating, despotic, costly and dangerous support of the United States. Without its religion, Mexico is irretrievably lost."

However, Porfirio Díaz was not completely supportive of the Catholic Church. Before his own presidency, Diaz had supported the Juarez regime, which implemented anti-clerical policies, such as expropriation of large tracts of Church-owned property and the forced laicization of Mexican clergy. Indeed, many Roman Catholic clergy, including the Blessed Miguel Pro, were executed during the anti-clerical Cristero War of Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles during the latter part of the Revolution.

Youth movement

As the Revolution progressed, the status of the University in relation to it changed several times; each time its students took different positions as well. Under different university directors, different revolutionary ideals were forced upon the student body. In many cases the curriculum would change as well. With each change, however, the importance of youth groups became more crucial. The university's students made up the bulk of the youth movement, chiefly composed of educated youth. During the Revolution, some viewed students as anti-revolutionary because of the image of the university as a safe haven for the rich and privileged. People engaged in the Revolution urged the university and students to become more involved and to accept the ideals and beliefs of the revolution.

The youth movements of the revolution were mainly confined to higher schools and especially the National University of Mexico. Young men used art, music, and poetry to speak out on the Revolution and encourage support. The leaders in government often made efforts to suppress such outlets. After the Revolution, new governments in turn gradually tried to suppress the freedoms of the University. By the 1920s, student protests were against the government.

End of the revolution

Historians debate the exact end of the "revolutionary period". From a military standpoint, it ended with the death of the Constitutional Army's primer jefe (First Chief) Venustiano Carranza in 1920, and the ascension to power of General Álvaro Obregón. Coup attempts and sporadic uprisings continued, for instance in the Cristero Wars of 1926–1929. Effective implementation of the social provisions of the 1917 Constitution of Mexico and near cession of revolutionary activity did not occur until the administration of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940). According to Robert McCaa, the total "demographic cost" during the Mexican Revolution 1910–1920 was approximately 2.1 million people.[13]

Cárdenas also abolished capital punishment, better known in Mexico as fusilamiento, death by firing squad. Cárdenas and the PRM's ability to control the republic without summary executions showed the revolutionary period was at its end.

Another major step was in 1940, when Cárdenas voluntarily relinquished all power to his successor Manuel Ávila Camacho, a legal transition that was unprecedented in Mexican history. In 1942, Ávila Camacho and all living ex-Presidents appeared on stage in the Mexico City Zócalo, in front of the Palacio Nacional, to encourage the Mexican people to support the Americans and British in World War II. This demonstration of political solidarity among diverse elements signaled the true end of the Revolution. Given its importance in national history, Mexican politicians and political parties refer frequently to the Revolution in their political rhetoric.

See also

{{{inline}}}

Notes

- ^ William Weber Johnson, Heroic Mexico: The violent emergence of a modern nation, Doubleday 1968, pg. 69

- ^ Michael Meyer, Mexican Rebel: Pascual Orozco and the Mexican Revolution 1910-1915, University of Nebraska 1967, pg. 44

- ^ Loprete, Carlos A. (2001). Iberoamérica. United States: Prentice Hall. pp. 175–177. ISBN 0130139920.

- ^ Alba, Victor. The Horizon Concise History of Mexico pg. 116

- ^ McLynn, Frank. Villa and Zapata pg. 24

- ^ Womack, John. 'Zapata and the Mexican Revolution pg. 10

- ^ Johnson, William. 'Heroic Mexico pg. 41

- ^ a b Clayton, Lawrence A. (2005). A History of Modern Latin America. United States: Wadsworth Publishing. pp. 285–286. ISBN 0534621589.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Friedrich Katz, “The Life and Times of Pancho Villa” 1998, p569

- ^ Mirande, Alfredo; Enriquez, Evangelina. (1981). La Chicana: The Mexican-American Woman.United States: University of Chicago Press. pp. 217–219. ISBN 9780226531601

- ^ General Zapata's great-great-nephew, Ricky Zapata

- ^ Lucas, Jeffrey Kent (2010). The Rightward Drift of Mexico's Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 81–132. ISBN 9780773436657.

- ^ McCaa, Robert."Missing Millions: The Demographic Costs of the Mexican Revolution." Mexican Studies Vol. 19, Iss. 2 (2003): 367–400.18 October.

Bibliography

- Many portions of this article are translations of excerpts from the article Revolución Mexicana in the Spanish Wikipedia.

General

- Britton, John A. Revolution and Ideology Images of the Mexican Revolution in the United States. Louisville: The University Press of Kentucky, 1995.

- Chasteen, John. Born In Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. New York:

- Doremus, Anne T. Culture, Politics, and National Identity in Mexican Literature and Film, 1929–1952. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2001.

- Documents on the Mexican Revolution Vol.1 Part 1. ed. Gene Z. Hanrahan. North Carolina: Documentary Publications, 1976

- Foster, David, W., ed. Mexican Literature A History. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994.

- Gonzales, Michael J. "The Mexican Revolution: 1910–1940" Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

- Hauss Charles, Smith Miriam, "Comparative Politics", Nelson Thomson Learning, Copyright 2000

- Hoy, Terry. "Octavio Paz: The Search for Mexican Identity." The Review of Politics 44:3 (July, 1982), 370–385.

- Lucas, Jeffrey Kent. The Rightward Drift of Mexico's Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

- Macias, Anna. "Women and the Mexican Revolution, 1910–1920." The Americas, 37:1 (Jul., 1980), 53–82.

- Mora, Carl J., Mexican Cinema: Reflections of a Society 1896–2004. Berkeley: University of California Press, 3rd edition, 2005

- Meyer, Jean A. The Cristero Rebellion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976, pp. 10–15

- Myers, Berbard S. Mexican Painting in Our Time. New York: Oxford University Press, 1956.

- Noble, Andrea, Photography and Memory in Mexico: Icons of Revolution. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010.

- Noble, Andrea, Mexican National Cinema, London: Routledge, 2005.

- Orellana, Margarita de, Filming Pancho Villa: How Hollywood Shaped the Mexican Revolution: North American Cinema and Mexico, 1911–1917. New York: Verso, 2007

- Paranagua, Paula Antonio. Mexican Cinema. London: British Film Institute, 1995.

- Quirk, Robert E. The Mexican Revolution and the Catholic Church 1910–1919. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973, pp. 1–249

- Reséndez Fuentes, Andrés. "Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution." The Americas 51, 4 (April 1995).

- Smith, Robert Freeman. The United States and Revolutionary Nationalism in Mexico 1916–1932. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972

- Soto, Shirlene Ann. Emergence of the Modern Mexican Woman. Denver: Arden Press, 1990.

- Swanson, Julia. "Murder in Mexico." History Today, June 2004. Vol.54, Issue 6; p 38–45

- Turner, Frederick C. "The Compatibility of Church and State in Mexico." Journal of Inter-American Studies, Vol 9, No 4, 1967, pp. 591–602

- Weinstock, Herbert. "Carlos Chavez." The Musical Quarterly 22:4 (Oct., 1936), 435–445.

Online

- Brunk, Samuel. The Banditry of Zapatismo in the Mexican Revolution The American Historical Review. Washington: April 1996, Volume 101, Issue 2, Page 331.

- Brunk, Samuel. "Zapata and the City Boys: In Search of a Piece of Revolution." Hispanic American Historical Review. Duke University Press, 1993.

- "From Soldaderas to Comandantes" Zapatista Direct Solidarity Committee. University of Texas.

- Gilbert, Dennis. "Emiliano Zapata: Textbook Hero." Mexican Studies. Berkley: Winter 2003, Volume 19, Issue 1, Page 127.

- Hardman, John. "Soldiers of Fortune" in the Mexican Revolution. "Postcards of the Mexican Revolution"

- Merewether Charles, Collections Curator, Getty Research Institute, "Mexico: From Empire to Revolution", Jan. 2002.

- Rausch George Jr. "The Exile and Death of Victoriano Huerta", The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 42, No. 2, May 1963 pp. 133–151.

- Tannenbaum, Frank. "Land Reform in Mexico". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 150, Economics of World Peace (July 1930), 238–247.

- Tuck, Jim. "Zapata and the Intellectuals." Mexico Connect, 1996–2006.

External links

- Mexican Revolution from the Library of Congress at Flickr Commons

- [1] EDSITEment spotlight The Centennial of the Mexican Revolution 1910-1920

- U.S. Library of Congress Country Study: Mexico

- Mexican Revolution of 1910 and Its Legacy, latinoartcommunity.org

- Women and the Mexican Revolution on the site of the University of Arizona

- Stephanie Creed, Kelcie McLaughlin, Christina Miller, Vince Struble, Mexican Revolution 1910–1920, Latin American Revolutions, course material for History 328, Truman State University (Missouri)

- Mexico: From Empire to Revolution, photographs and commentary on the site of the J. Paul Getty Trust

- Mexican Revolution, ca. 1910-1917 Photos and postcards in color and in black and white, some with manuscript letters, postmarks, and stamps from the collection at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Papers of E. K. Warren & Sons, 1884–1973, ranchers in Mexico, Texas and New Mexico, held at Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library at Texas Tech University

- Mexican Revolution, in the "Boys' Historical Clothing" website. This is a overview of the Revolution with an treatment of the impact on children.

- SMU's Mexic : graphs from the DeGolyer Library contains contains dozens of photographs related to the Mexican Revolution.

- Time line of the Mexican Revolution