Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to before recorded history.

Shipbuilding and ship repairs, both commercial and military, are referred to as the "naval engineer". The construction of boats is a similar activity called boat building.

The dismantling of ships is called ship breaking.

History

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence indicates that humans arrived on Borneo at least 120,000 years ago, probably by sea from Asia-China mainland during an ice age period when the sea was lower and distances between islands shorter (See History of Borneo and Papua New Guinea). The ancestors of Australian Aborigines and New Guineans also went across the Lombok Strait to Sahul by boat over 50,000 years ago.

4th millennium BC

Evidence from Ancient Egypt shows that the early Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull as early as 3000 BC. The Archaeological Institute of America reports[1] that some of the oldest ships yet unearthed are known as the Abydos boats. These are a group of 14 discovered ships in Abydos that were constructed of wooden planks which were "sewn" together. Discovered by Egyptologist David O'Connor of New York University,[2] woven straps were found to have been used to lash the planks together,[1] and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams.[1] Because the ships are all buried together and near a mortuary belonging to Pharaoh Khasekhemwy,[2] originally they were all thought to have belonged to him, but one of the 14 ships dates to 3000 BC,[2] and the associated pottery jars buried with the vessels also suggest earlier dating.[2] The ship dating to 3000 BC was 75 feet long[2] and is now thought to perhaps have belonged to an earlier pharaoh.[2] According to professor O'Connor, the 5,000-year-old ship may have even belonged to Pharaoh Aha.[2]

3rd millennium BC

Early Egyptians also knew how to assemble planks of wood with treenails to fasten them together, using pitch for caulking the seams. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter vessel sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza in the Fourth Dynasty around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque. Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten the planks of this ship together with mortise and tenon joints.[1]

The oldest known tidal dock in the world was built around 2500 BC during the Harappan civilisation at Lothal near the present day Mangrol harbour on the Gujarat coast in India. Other ports were probably at Balakot and Dwarka. However, it is probable that many small-scale ports, and not massive ports, were used for the Harappan maritime trade.[3] Ships from the harbour at these ancient port cities established trade with Mesopotamia.[4] Shipbuilding and boatmaking may have been prosperous industries in ancient India.[5] Native labourers may have manufactured the flotilla of boats used by Alexander the Great to navigate across the Hydaspes and even the Indus, under Nearchos.[5] The Indians also exported teak for shipbuilding to ancient Persia.[6] Other references to Indian timber used for shipbuilding is noted in the works of Ibn Jubayr.[6]

2nd millennium BC

The ships of Ancient Egypt's Eighteenth Dynasty were typically about 25 meters (80 ft) in length, and had a single mast, sometimes consisting of two poles lashed together at the top making an "A" shape. They mounted a single square sail on a yard, with an additional spar along the bottom of the sail. These ships could also be oar propelled.[7]

The ships of Phoenicia seems to have been of a similar design. The Greeks and probably others introduced the use of multiple banks of oars for additional speed, and the ships were of a light construction for speed and so they could be carried ashore.

1st millennium BC

The naval history of China stems back to the Spring and Autumn Period (722 BC–481 BC) of the ancient Chinese Zhou Dynasty. The Chinese built large rectangular barges known as "castle ships", which were essentially floating fortresses complete with multiple decks with guarded ramparts.

Early 1st millennium AD

The ancient Chinese also built ramming vessels as in the Greco-Roman tradition of the trireme, although oar-steered ships in China lost favor very early on since it was in the 1st century China that the stern-mounted rudder was first developed. This was dually met with the introduction of the Han Dynasty junk ship design in the same century.

Medieval Europe, Sung China, Abbasid Caliphate, Pacific Islanders

Viking longships developed from an alternate tradition of clinker-built hulls fastened with leather thongs[citation needed]. Sometime around the 12th century, northern European ships began to be built with a straight sternpost, enabling the mounting of a rudder, which was much more durable than a steering oar held over the side. Development in the Middle Ages favored "round ships", with a broad beam and heavily curved at both ends. Another important ship type was the galley which was constructed with both sails and oars.

An insight into ship building in the North Sea/Baltic areas of the early medieval period was found at Sutton Hoo, England, where a ship was buried with a chieftain. It was nearly 90 feet long and, at its widest, 14 feet wide. Upward from the keel, the hull was made by overlapping nine planks on either side with rivets fastening the oaken planks together.In its days on the whale-road it could hold upwards of thirty men.

The first extant treatise on shipbuilding was written ca. 1436 by Michael of Rhodes,[8] a man who began his career as an oarsman on a Venetian galley in 1401 and worked his way up into officer positions. He wrote and illustrated a book that contains a treatise on ship building, a treatise on mathematics, much material on astrology, and other materials. His treatise on shipbuilding treats three kinds of galleys and two kinds of round ships.[9]

Outside Medieval Europe, great advances were being made in shipbuilding. The shipbuilding industry in Imperial China reached its height during the Sung Dynasty, Yuan Dynasty, and early Ming Dynasty, building commercial vessels that by the end of this period were to reach a size and sophistication far exceeding that of contemporary Europe. The mainstay of China's merchant and naval fleets was the junk, which had existed for centuries, but it was at this time that the large ships based on this design were built. During the Sung period (960–1279 AD), the establishment of China's first official standing navy in 1132 AD and the enormous increase in maritime trade abroad (from Heian Japan to Fatimid Egypt) allowed the shipbuilding industry in provinces like Fujian to thrive as never before. The largest seaports in the world were in China and included Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Xiamen.

In the Islamic world, shipbuilding thrived at Basra and Alexandria, the dhow, felucca, baghlah and the sambuk, became symbols of successful maritime trade around the Indian Ocean; from the ports of East Africa to Southeast Asia and the ports of Sindh and Hind (India) during the Abbasid period.

At this time islands spread over vast distances across the Pacific Ocean were being colonised by the Melenesians and Polynesians, who built giant canoes and progressed to great catamarans.

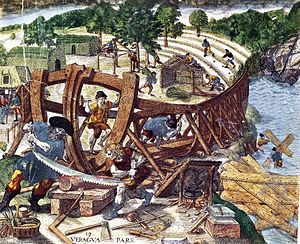

Early Modern

With the development of the carrack, the west moved into a new era of building the first regular ocean going vessels. These were of unprecedented size, complexity and cost. Shipyards became large industrial complexes and the ships built were financed by consortia of investors.

These considerations led to the documentation of design and construction practices in what had previously been a secretive trade run by master shipwrights, and ultimately led to the field of naval architecture, where professional designers and draughtsmen played an increasingly important role.[10] Even so, construction techniques changed only very gradually. The ships of the Napoleonic Wars were still built more or less to the same basic plan as those of the Spanish Armada of two centuries earlier but there had been numerous subtle improvements in ship design and construction throughout this period. For instance, the introduction of tumblehome; adjustments to the shapes of sails and hulls; the introduction of the wheel; the introduction of hardened copper fastenings below the waterline; the introduction of copper sheathing as a deterrent to shipworm and fouling; etc.[11]

Industrial Revolution

Other than its widespread use in fastenings, Iron was gradually adopted in ship construction, initially in discrete areas in a wooden hull needing greater strength, (e.g. as deck knees, hanging knees, knee riders and the like). Then, in the form of plates rivetted together and made watertight, it was used to form the hull itself. Initially copying wooden construction traditions with a frame over which the hull was fastened, Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Great Britain of 1843 was the first radical new design, being built entirely of wrought iron. Despite her success, and the great savings in cost and space provided by the iron hull, compared to a copper sheathed counterpart, there remained problems with fouling due to the adherence of weeds and barnacles. As a result composite construction remained the dominant approach where fast ships were required, with wooden timbers laid over an iron frame (the Cutty Sark is a famous example). Later Great Britain's iron hull was sheathed in wood to enable it to carry a copper-based sheathing. Brunel's Great Eastern represented the next great development in shipbuilding. Built in association with John Scott Russell, it used longitudinal stringers for strength, inner and outer hulls, and bulkheads to form multiple watertight compartments. Steel also supplanted wrought iron when it became readily available in the latter half of the 19th century, providing great savings when compared with iron in cost and weight. Wood continued to be favored for the decks, and is still the rule as deckcovering for modern cruise ships. Scotts Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd, Greenock, Scotland is a superb example of a shipbuilding firm that lasted nearly 300 years.[12]

Modern worldwide shipbuilding industry

In the 20th century, shipbuilding (which encompasses the shipyards, the marine equipment manufacturers, and many related service and knowledge providers) grew as an important and strategic industry in a number of countries around the world. This importance stems from:

- The large number of skilled workers required directly by the shipyard, along with supporting industries such as steel mills, railroads and engine manufacturers; and

- A nation's need to manufacture and repair its own navy and vessels that support its primary industries

Historically, the industry has suffered from the absence of global rules and a tendency towards (state-supported) over-investment due to the fact that shipyards offer a wide range of technologies, employ a significant number of workers, and generate income as the shipbuilding market is global.

Shipbuilding is therefore an attractive industry for developing nations. Japan used shipbuilding in the 1950s and 1960s to rebuild its industrial structure; South Korea started to make shipbuilding a strategic industry in the 1970s, and China is now in the process of repeating these models with large state-supported investments in this industry. Conversely, Croatia is privatising its shipbuilding industry.

As a result, the world shipbuilding market suffers from over-capacities, depressed prices (although the industry experienced a price increase in the period 2003–2005 due to strong demand for new ships which was in excess of actual cost increases), low profit margins, trade distortions and widespread subsidisation. All efforts to address the problems in the OECD have so far failed, with the 1994 international shipbuilding agreement never entering into force and the 2003–2005 round of negotiations being paused in September 2005 after no agreement was possible. After numerous efforts to restart the negotiations these were formally terminated in December 2010. The OECD's Council Working Party on Shipbuilding (WP6) will continue its efforts to identify and progressively reduce factors that distort the shipbuilding market.

Where state subsidies have been removed and domestic industrial policies do not provide support, in high-cost nations shipbuilding has usually gone into steady, if not rapid, decline. The British shipbuilding industry is a prime example of this. From a position in the early 1970s where British yards could still build the largest types of sophisticated merchant ships, British shipbuilders today have been reduced to a handful specialising in defence contracts and repair work. In the U.S.A., the Jones Act (which places restrictions on the ships that can be used for moving domestic cargoes) has meant that merchant shipbuilding has continued, but such protection has failed to penalise shipbuilding inefficiencies. The consequence of this is contract prices that are far higher than those of any other nation building oceangoing ships.

World shipbuilding industry in the 21st century

China is the largest shipbuilder in the world in terms of compensated gross tons of ships as of 2010, at a total of 15.9 million tons, followed by South Korea with 11.77 million compensated gross tons. In terms of monetary value of the ships, South Korea is still the largest shipbuilder in the world as of 2010, followed by China, at a total value of $30.61 billion.[13]

Japan lost its leading position in the industry to South Korea in 2004,[14] and its market share has since fallen sharply. The entire European market share has fallen to only a tenth of South Korea's, and the outputs of the rest of the world have become negligible.

Modern shipbuilding manufacturing techniques

Modern shipbuilding makes considerable use of prefabricated sections. Entire multi-deck segments of the hull or superstructure will be built elsewhere in the yard, transported to the building dock or slipway, then lifted into place. This is known as "block construction". The most modern shipyards pre-install equipment, pipes, electrical cables, and any other components within the blocks, to minimize the effort needed to assemble or install components deep within the hull once it is welded together. This was first introduced by Alstom Chantiers de l'Atlantique when they built the largest Ocean Liner in the world Cunard's RMS Queen Mary 2.

Ship design work, also called naval architecture, may be conducted using a ship model basin. Modern ships, since roughly 1940, have been produced almost exclusively of welded steel. Early welded steel ships used steels with inadequate fracture toughness, which resulted in some ships suffering catastrophic brittle fracture structural cracks (see problems of the Liberty ship). Since roughly 1950, specialized steels such as ABS Steels with good properties for ship construction have been used. Although it is commonly accepted that modern steel has eliminated brittle fracture in ships, some controversy still exists.[15] Brittle fracture of modern vessels continues to occur from time to time as the use of grade A and grade B steel of unknown toughness or fracture appearance transition temperature (FATT) in way of ships' side shells can be less than adequate for all ambient conditions.[16]

Ship repair industry

All ships need maintenance and repairs. A part of these jobs must be carried out under the supervision of the Classification Society. A lot of maintenance it is carried out while at sea or in port by ship's staff. However a large number of repair and maintenance works can only be carried out while the ship is out of commercial operation, in a Shiprepair Yard. Prior to undergoing repairs, tankers must dock at a Deballasting Station for if necessary completing the tank cleaning operations and pumping ashore its slops (dirty cleaning water and hydrocarbon residues).

See also

- Boat building

- List of shipbuilders and shipyards

- List of Russian shipbuilders

- Marine propulsion

- Naval architecture

- Shipbuilding (song)

References

- ^ a b c d Ward, Cheryl. "World's Oldest Planked Boats", in Archaeology (Volume 54, Number 3, May/June 2001). Archaeological Institute of America.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schuster, Angela M.H. "This Old Boat", 11 December 2000. Archaeological Institute of America.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory. Meluhha. in: J. Reade (ed.) The Indian Ocean in Antiquity. London: Kegan Paul Intl. 1996, 133–208

- ^ (eg Lal 1997: 182–188)

- ^ a b Tripathi, page 145

- ^ a b Hourani & Carswel, page 90

- ^ Robert E. Krebs, Carolyn A. Krebs (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Ancient World. Greenwood PressScience. ISBN 0313313423.

- ^ "Michael of Rhodes: A medieval mariner and his manuscript". Meseo Galileo. Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology. 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Pamela O. Long, David McGee, and Allan M. Stahl,eds. The Book of Michael of Rhodes: A Fifteenth-Century Maritime Manuscript, 3 vols. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009)

- ^ Colin Tipping,"Technical Change & the Ship Draughtsman." THE MARINER'S MIRROR 84, No.4, 1998, page 458 foll.

- ^ McCarthy, M., 2005 Ship’s Fastenings: from sewn boat to steamship. Texas A&M Press. College Station. ISBN 1585444510

- ^ Johnston Fraser Robb, "Scotts of Greenock,1820-1920, A Family Enterprise", 1993", British Library CD Ethos 513119.

- ^ [1]

- ^ James Brooke (2005-01096). "Korea reigns in shipbuilding, for now". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Drouin, P: "Brittle Fracture in ships - a lingering problem", page 229. Ships and Offshore Structures, Woodhead Publishing, 2006.

- ^ "Marine Investigation Report - Hull Fracture Bulk Carrier Lake Carling". Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 19 March 2002. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1967). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 145. ISBN 8120800184.

- Hourani, George Fadlo (1995). Arab Seafaring: In the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times. Princeton University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0691000328.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Shipbuilding Picture Dictionary

- Trading Places—interactive history of Liverpool docks

- U.S. Shipbuilding—extensive information about the U.S. shipbuilding industry, including over 500 pages of U.S. shipyard construction records

- Shipyards United States—from GlobalSecurity.org

- Shipbuilding in Canada

- North Vancouver's Wartime Shipbuilding

- Shipbuilding News

- Bataviawerf - the Historic Dutch East Indiaman Ship Yard—Shipyard of the historic ships Batavia and Zeven Provincien in the Netherlands, since 1985 here have been great ships reconstructed using old construction methods.

- Photos of the reconstruction of the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia—Photo web site about the reconstruction of the Batavia on the shipyard Batavia werf, a 16th century East Indiaman in the Netherlands. The site is constantly expanding with more historic images as in 2010 the shipyard celebrates its 25th year.