Antoninus Pius

| Antoninus Pius | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15th Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

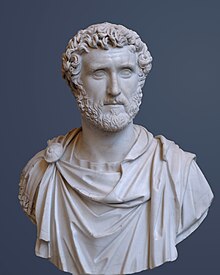

Bust of Antoninus Pius, at Glyptothek, Munich | |||||

| Reign | 11 July 138 – 7 March 161 | ||||

| Predecessor | Hadrian | ||||

| Successor | Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus | ||||

| Born | 19 September 86 near Lanuvium, Italy | ||||

| Died | 7 March 161 (aged 74) Lorium | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Faustina | ||||

| Issue | Faustina the Younger, one other daughter and two sons, all died before 138 (natural); Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (adoptive) | ||||

| |||||

| Imperial Dynasty | Antonine | ||||

| Father | Titus Aurelius Fulvus (natural); Hadrian (adoptive, from 25 Feb. 138) | ||||

| Mother | Arria Fadilla | ||||

Antoninus Pius (Latin: Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius;[1][2] born 19 September 86AD – died 7 March 161AD), also known as Antoninus, was Roman Emperor from 138AD to 161AD. He was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty and the Aurelii.[3] He acquired the name Pius after his accession to the throne, either because he compelled the Senate to deify his adoptive father Hadrian,[4] or because he had saved senators sentenced to death by Hadrian in his later years.[5]

Early life

Childhood and family

He was born as the only child of Titus Aurelius Fulvus, consul in 89[3] whose family came from Nemausus (modern Nîmes).[6] He was born near Lanuvium[7] and his mother was Arria Fadilla. Antoninus’ father and paternal grandfather died when he was young and he was raised by Gnaeus Arrius Antoninus,[3] his maternal grandfather, reputed by contemporaries to be a man of integrity and culture and a friend of Pliny the Younger. His mother married Publius Julius Lupus (a man of consular rank) suffect consul in 98, and two daughters, Arria Lupula and Julia Fadilla, were born from that union.[8]

Marriage and children

Some time between 110 and 115, he married Annia Galeria Faustina the Elder.[1] They are believed to have enjoyed a happy marriage. Faustina was the daughter of consul Marcus Annius Verus[3] and Rupilia Faustina (a half-sister to Roman Empress Vibia Sabina). Faustina was a beautiful woman, well known for her wisdom. She spent her whole life caring for the poor and assisting the most disadvantaged Romans.

Faustina bore Antoninus four children, two sons and two daughters.[9] They were:

- Marcus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus (died before 138); his sepulchral inscription has been found at the Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome.[10]

- Marcus Galerius Aurelius Antoninus (died before 138); his sepulchral inscription has been found at the Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome.[10] His name appears on a Greek Imperial coin.

- Aurelia Fadilla (died in 135); she married Lucius Lamia Silvanus, consul 145. She appeared to have no children with her husband and her sepulchral inscription has been found in Italy.[11]

- Annia Galeria Faustina Minor or Faustina the Younger (between 125–130–175), a future Roman Empress, married her maternal cousin, future Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius in 146.[6]

When Faustina died in 141, Antoninus was greatly distressed.[12] In honor of her memory, he asked the Senate to deify her as a goddess, and authorised the construction of a temple to be built in the Roman Forum in her name, with priestesses serving in her temple.[13] He had various coins with her portrait struck in her honor. These coins were scripted ‘DIVAE FAUSTINA’ and were elaborately decorated. He further created a charity which he founded and called it Puellae Faustinianae or Girls of Faustina, which assisted orphaned girls.[1] Finally, Antoninus created a new alimenta (see Grain supply to the city of Rome).

Favor with Hadrian

Having filled the offices of quaestor and praetor with more than usual success,[14] he obtained the consulship in 120;[1] he was next appointed by the Emperor Hadrian as one of the four proconsuls to administer Italia,[15] then greatly increased his reputation by his conduct as proconsul of Asia, probably during 134–135.[15] He acquired much favor with the Emperor Hadrian, who adopted him as his son and successor on 25 February 138,[16] after the death of his first adopted son Lucius Aelius,[17] on the condition that Antoninus would in turn adopt Marcus Annius Verus, the son of his wife's brother, and Lucius, son of Aelius Verus, who afterwards became the emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.[1]

Emperor

On his accession, Antoninus' name became "Imperator Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pontifex Maximus". One of his first acts as Emperor was to persuade the Senate to grant divine honours to Hadrian, which they had at first refused;[18] his efforts to persuade the Senate to grant these honours is the most likely reason given for his title of Pius (dutiful in affection; compare pietas).[19] Two other reasons for this title are that he would support his aged father-in-law with his hand at Senate meetings, and that he had saved those men that Hadrian, during his period of ill-health, had condemned to death.[6] He built temples, theaters, and mausoleums, promoted the arts and sciences, and bestowed honours and financial rewards upon the teachers of rhetoric and philosophy.[1] Antoninus made few initial changes when he became emperor, leaving intact as far as possible the arrangements instituted by Hadrian.[18]

There are no records of any military related acts in his time in which he participated. One modern scholar has written "It is almost certain not only that at no time in his life did he ever see, let alone command, a Roman army, but that, throughout the twenty-three years of his reign, he never went within five hundred miles of a legion".[20] His reign was the most peaceful in the entire history of the Principate;[21] while there were several military disturbances throughout the Empire in his time, in Mauretania, Iudaea, and amongst the Brigantes in Britannia, none of them are considered serious.[21] It was however in Britain that Antoninus decided to follow a new, more aggressive path, with the appointment of a new governor in 139, Quintus Lollius Urbicus.[18]

Under instructions from the emperor, he undertook an invasion of southern Scotland, winning some significant victories, and constructing the Antonine Wall[22] from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde, although it was soon abandoned for reasons that are still not quite clear.[23] There were also some troubles in Dacia Inferior which required the granting of additional powers to the procurator governor and the dispatchment of additional soldiers to the province.[23] Also during his reign the governor of Upper Germany, probably Caius Popillius Carus Pedo, built new fortifications in the Agri Decumates, advancing the Limes Germanicus fifteen miles forward in his province and neighboring Raetia.[24]

Nevertheless, Antoninus was virtually unique among emperors in that he dealt with these crises without leaving Italy once during his reign,[25] but instead dealt with provincial matters of war and peace through their governors or through imperial letters to the cities such as Ephesus (of which some were publicly displayed). This style of government was highly praised by his contemporaries and by later generations.[26]

Of the public transactions of this period there is only the scantiest of information, but, to judge by what is extant, those twenty-two years were not remarkably eventful in comparison to those before and after his reign. However, he did take a great interest in the revision and practice of the law throughout the empire.[27] Although he was not an innovator, he would not follow the absolute letter of the law; rather he was driven by concerns over humanity and equality, and introduced into Roman law many important new principles based upon this notion.[27]

In this, the emperor was assisted by five chief lawyers: L. Fulvius Aburnius Valens, an author of legal treatises; L. Volusius Maecianus, chosen to conduct the legal studies of Marcus Aurelius, and author of a large work on Fidei Commissa (Testamentary Trusts); L. Ulpius Marcellus, a prolific writer; and two others.[27] His reign saw the appearance of the Institutes of Gaius, an elementary legal manual for beginners (see Gaius (jurist)).[27]

Antoninus passed measures to facilitate the enfranchisement of slaves.[28] In criminal law, Antoninus introduced the important principle that accused persons are not to be treated as guilty before trial.[28] He also asserted the principle, that the trial was to be held, and the punishment inflicted, in the place where the crime had been committed. He mitigated the use of torture in examining slaves by certain limitations. Thus he prohibited the application of torture to children under fourteen years, though this rule had exceptions.[28]

One highlight during his reign occurred in 148, with the nine-hundredth anniversary of the foundation of Rome being celebrated by the hosting of magnificent games in Rome.[29] It lasted a number of days, and a host of exotic animals were killed, including elephants, giraffes, tigers, rhinoceroses, crocodiles and hippopotami. While this increased Antoninus’s popularity, the frugal emperor had to debase the Roman currency. He decreased the silver purity of the denarius from 89% to 83.5% — the actual silver weight dropping from 2.88 grams to 2.68 grams.[23][30]

Scholars place Antoninus Pius as the leading candidate for fulfilling the role as a friend of Rabbi Judah the Prince. According to the Talmud (Avodah Zarah 10a-b), Rabbi Judah was very wealthy and greatly revered in Rome. He had a close friendship with "Antoninus", possibly Antoninus Pius,[31] who would consult Rabbi Judah on various worldly and spiritual matters.

After the longest reign since Augustus (surpassing Tiberius by a couple of months), Antoninus died of fever at Lorium in Etruria,[32] about twelve miles (19 km) from Rome, on 7 March 161,[33] giving the keynote to his life in the last word that he uttered when the tribune of the night-watch came to ask the password—"aequanimitas" (equanimity).[34] His body was placed in Hadrian's mausoleum, a column was dedicated to him on the Campus Martius,[1] and the temple he had built in the Forum in 141 to his deified wife Faustina was rededicated to the deified Faustina and the deified Antoninus.[34]

Historiography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

The only account of his life handed down to us is that of the Augustan History, an unreliable and mostly fabricated work. Nevertheless, it still contains information that is considered reasonably sound – for instance, it is the only source that mentions the erection of the Antonine Wall in Britain.[35] Antoninus is unique among Roman emperors in that he has no other biographies. Historians have therefore turned to public records for what details we know.

In later scholarship

Antoninus in many ways was the ideal of the landed gentleman praised not only by ancient Romans, but also by later scholars of classical history, such as Edward Gibbon or the author of the article on Antoninus Pius in the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica:

A few months afterwards, on Hadrian's death, he was enthusiastically welcomed to the throne by the Roman people, who, for once, were not disappointed in their anticipation of a happy reign. For Antoninus came to his new office with simple tastes, kindly disposition, extensive experience, a well-trained intelligence and the sincerest desire for the welfare of his subjects. Instead of plundering to support his prodigality, he emptied his private treasury to assist distressed provinces and cities, and everywhere exercised rigid economy (hence the nickname κυμινοπριστης "cummin-splitter"). Instead of exaggerating into treason whatever was susceptible of unfavorable interpretation, he turned the very conspiracies that were formed against him into opportunities for demonstrating his clemency. Instead of stirring up persecution against the Christians, he extended to them the strong hand of his protection throughout the empire. Rather than give occasion to that oppression which he regarded as inseparable from an emperor's progress through his dominions, he was content to spend all the years of his reign in Rome, or its neighbourhood.

Later historians had a more nuanced view of his reign. According to the historian J. B. Bury,

however estimable the man, Antoninus was hardly a great statesman. The rest which the Empire enjoyed under his auspices had been rendered possible through Hadrian’s activity, and was not due to his own exertions; on the other hand, he carried the policy of peace at any price too far, and so entailed calamities on the state after his death. He not only had no originality or power of initiative, but he had not even the insight or boldness to work further on the new lines marked out by Hadrian.[36]

Inevitably, the surviving evidence is not complete enough to determine whether one should interpret, with older scholars, that he wisely curtailed the activities of the Roman Empire to a careful minimum, or perhaps that he was uninterested in events away from Rome and Italy and his inaction contributed to the pressing troubles that faced not only Marcus Aurelius but also the emperors of the third century. German historian Ernst Kornemann has had it in his Römische Geschichte [2 vols., ed. by H. Bengtson, Stuttgart 1954] that the reign of Antoninus comprised "a succession of grossly wasted opportunities," given the upheavals that were to come. There is more to this argument, given that the Parthians in the East were themselves soon to make no small amount of mischief after Antoninus' passing. Kornemann's brief is that Antoninus might have waged preventive wars to head off these outsiders.

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Weigel, Antoninus Pius Cite error: The named reference "Weigel, Antoninus Pius" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ In Classical Latin, Antoninus' name would be inscribed as TITVS AELIVS HADRIANVS ANTONINVS AVGVSTVS PIVS.

- ^ a b c d Bowman, pg. 150

- ^ Birley, pg. 54; Dio, 70:1:2

- ^ Birley, pg. 55, citing the Historia Augusta, Life of Hadrian 24.4

- ^ a b c Bury, pg. 523 Cite error: The named reference "Bury, pg. 523" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Harvey, Paul B., Religion in republican Italy, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pg. 134; Canduci, pg. 39

- ^ Birley, pg. 242; Historia Augusta, Life of Antoninus Pius 1:6

- ^ Birley, pg. 34; Historia Augusta, Life of Antoninus Pius 1:7

- ^ a b Magie, David, Historia Augusta (1921), Life of Antoninus Pius, Note 6

- ^ Magie, David, Historia Augusta (1921), Life of Antoninus Pius, Note 7

- ^ Bury, pg. 528

- ^ Birley, pg. 77; Historia Augusta, Life of Antoninus Pius 6:7

- ^ Traver, Andrew G., From polis to empire, the ancient world, c. 800 B.C.-A.D. 500, (2002) pg. 33; Historia Augusta, Life of Antoninus Pius 2:9

- ^ a b Bowman, pg. 149

- ^ Bowman,pg. 148

- ^ Bury, pg. 517

- ^ a b c Bowman, pg. 151

- ^ Birley, pg. 55; Canduci, pg. 39

- ^ J. J. Wilkes, The Journal of Roman Studies, Volume LXXV 1985, ISSN 0075-4358, p. 242.

- ^ a b Bury, pg. 525

- ^ Bowman, pg. 152

- ^ a b c Bowman, pg. 155

- ^ Birley, pg. 113

- ^ Speidel, Michael P., Riding for Caesar: The Roman Emperors' Horse Guards, Harvard University Press, 1997, pg. 50; Canduci, pg. 40

- ^ See Victor, 15:3

- ^ a b c d Bury, pg. 526

- ^ a b c Bury, pg. 527

- ^ Bowman, pg, 154

- ^ Tulane University "Roman Currency of the Principate"

- ^ A. Mischcon, Abodah Zara, p.10a Soncino, 1988. Mischcon cites various sources, "SJ Rappaport... is of opinion that our Antoninus is Antoninus Pius." Other opinions cited suggest "Antoninus" was Caracalla, Lucius Verus or Alexander Severus.

- ^ Bowman, pg. 156; Victor, 15:7

- ^ Bowman, pg. 156

- ^ a b Bury, pg. 532

- ^ Historia Augusta, Life of Antoninus Pius 5:4

- ^ Bury, pg. 524

References

- Primary sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 70, [1]

- Aurelius Victor, "Epitome de Caesaribus", English version of Epitome de Caesaribus

- Historia Augusta, The Life of Antoninus Pius, English version of Historia Augusta Note that the Historia Augusta includes pseudohistorical elements.

- Secondary sources

- Weigel, Richard D., "Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138–161)", De Imperatoribus Romanis

- Bowman, Alan K. The Cambridge Ancient History: The High Empire, A.D. 70–192. Cambridge University Press, 2000

- Birley, Anthony, Marcus Aurelius, Routledge, 2000

- Canduci, Alexander (2010), Triumph & Tragedy: The Rise and Fall of Rome's Immortal Emperors, Pier 9, ISBN 978-1-74196-598-8

- Bury, J. B. A History of the Roman Empire from its Foundation to the Death of Marcus Aurelius (1893)

- Hüttl, W. Antoninus Pius vol. I & II, Prag 1933 & 1936.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antoninus Pius". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. This source lists:

- Bossart-Mueller, Zur Geschichte des Kaisers A. (1868)

- Bryant, The Reign of Antonine (Cambridge Historical Essays, 1895)

- Lacour-Gayet, A. le Pieux et son Temps (1888)

- Watson, P. B. Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (London, 1884), chap. ii.

External links