Theodosius I

| Theodosius I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67th Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

| File:Theodosius-1-.jpg Theodosius | |||||

| Reign | 19 January 379 – 15 May 392 (emperor in the East; 15 May 392 – 17 January 395 (whole empire) | ||||

| Predecessor | Valens in the East Gratian in the West Valentinian II in the West | ||||

| Successor | Arcadius in the East; Honorius in the West | ||||

| Born | 11 January 347 Cauca, or Italica, near Seville, modern Spain | ||||

| Died | 17 January 395 (aged 48) Mediolanum | ||||

| Burial | Constantinople, Modern Day Istanbul | ||||

| Spouse | 1) Aelia Flaccilla (?-385) 2) Galla (?-394) | ||||

| Issue | Arcadius Honorius Pulcheria Galla Placidia | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Theodosian | ||||

| Father | Theodosius the Elder | ||||

| Mother | Thermantia | ||||

| Religion | Catholic Orthodoxy | ||||

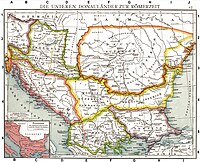

Theodosius I (Template:Lang-la;[1] 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also known as Theodosius the Great, was Roman Emperor from 379 to 395. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and the western halves of the Roman Empire. During his reign, the Goths secured control of Illyricum after the Gothic War, establishing their homeland south of the Danube within the empire's borders. He also issued decrees that effectively made Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire.[2][3]

He is recognized by the Eastern Orthodox Church as Saint Theodosius. He defeated the usurpers Magnus Maximus and Eugenius and fostered the destruction of some prominent pagan temples: the Serapeum in Alexandria, the Temple of Apollo in Delphi, and the Vestal Virgins in Rome. After his death, Theodosius' sons Arcadius and Honorius inherited the East and West halves respectively, and the Roman Empire was never again re-united. In 393, he banned the Olympics in Ancient Greece. It was not until the 19th century that the Olympics were held again.

Career

Theodosius was born in Cauca or Italica, Hispania,[4] to senior military officer Theodosius the Elder.[5] He accompanied his father to Britannia to help quell the Great Conspiracy in 368. He was military commander (dux) of Moesia, a Roman province on the lower Danube, in 374. However, shortly thereafter, and at about the same time as the sudden disgrace and execution of his father, Theodosius retired to Spain. The reason for his retirement, and the relationship (if any) between it and his father's death is unclear. It is possible that he was dismissed from his command by the emperor Valentinian I after the loss of two of Theodosius' legions to the Sarmatians in late 374.

The death of Valentinian I in 375 created political pandemonium. Fearing further persecution on account of his family ties, Theodosius abruptly retired to his family estates in the province of Gallaecia (present day Galicia, Spain) where he adapted to the life of a provincial aristocrat.

From 364 to 375, the Roman Empire was governed by two co-emperors, the brothers Valentinian I and Valens; when Valentinian died in 375, his sons, Valentinian II and Gratian, succeeded him as rulers of the Western Roman Empire. In 378, after Valens was killed in the Battle of Adrianople, Gratian invited Theodosius to take command of the Illyrian army. As Valens had no successor, Gratian's appointment of Theodosius amounted to a de facto invitation for Theodosius to become co-Augustus for the East. Gratian was killed in a rebellion in 383, Theodosius then appointed his elder son, Arcadius, his co-ruler for the East. After the death in 392 of Valentinian II, whom Theodosius had supported against a variety of usurpations, Theodosius ruled as sole Emperor, appointing his younger son Honorius Augustus as his co-ruler for the West (Milan, on 23 January 393) and by defeating the usurper Eugenius on 6 September 394, at the Battle of the Frigidus (Vipava river, modern Slovenia) he restored peace.

Family

By his first wife, the probably Spanish Aelia Flaccilla Augustus, he had two sons, Arcadius and Honorius and a daughter, Aelia Pulcheria; Arcadius was his heir in the East and Honorius in the West. Both Aelia Flaccilla and Pulcheria died in 385.

His second wife (but never declared Augusta) was Galla, daughter of the emperor Valentinian I and his second wife Justina. Theodosius and Galla had a son Gratian, born in 388 who died young and a daughter Aelia Galla Placidia (392–450). Placidia was the only child who survived to adulthood and later became an Empress.

Diplomatic policy with the Goths

The Goths and their allies (Vandali, Taifalae, Bastarnae and the native Carpi) entrenched in the provinces of Dacia and eastern Pannonia Inferior consumed Theodosious' attention. The Gothic crisis was so dire that his co-Emperor Gratian relinquished control of the Illyrian provinces and retired to Trier in Gaul to let Theodosius operate without hindrance. A major weakness in the Roman position after the defeat at Adrianople was the recruiting of barbarians to fight against other barbarians. In order to reconstruct the Roman Army of the West, Theodosius needed to find able bodied soldiers and so he turned to the most capable men readily at hand: the barbarians recently settled in the Empire. This caused many difficulties in the battle against barbarians since the newly recruited fighters had little or no loyalty to Theodosius.

Theodosius was reduced to the costly expedient of shipping his recruits to Egypt and replacing them with more seasoned Romans, but there were still switches of allegiance that resulted in military setbacks. Gratian sent generals to clear the dioceses of Illyria (Pannonia and Dalmatia) of Goths, and Theodosius was able finally to enter Constantinople on 24 November 380, after two seasons in the field. The final treaties with the remaining Gothic forces, signed 3 October 382, permitted large contingents of primarily Thervingian Goths to settle along the southern Danube frontier in the province of Thrace and largely govern themselves.

The Goths now settled within the Empire had, as a result of the treaties, military obligations to fight for the Romans as a national contingent, as opposed to being fully integrated into the Roman forces.[6] However, many Goths would serve in Roman legions and others, as foederati, for a single campaign, while bands of Goths switching loyalties became a destabilizing factor in the internal struggles for control of the Empire.

In 390 the population of Thessalonica rioted in complaint against the presence of the local Gothic garrison. The garrison commander was killed in the violence, so Theodosius ordered the Goths to kill all the spectators in the circus as retaliation; Theodoret, a contemporary witness to these events, reports:

"...the anger of the Emperor rose to the highest pitch, and he gratified his vindictive desire for vengeance by unsheathing the sword most unjustly and tyrannically against all, slaying the innocent and guilty alike. It is said seven thousand perished without any forms of law, and without even having judicial sentence passed upon them; but that, like ears of wheat in the time of harvest, they were alike cut down."[7]

Theodosius was threatened with excommunication by the bishop of Milan, Saint Ambrose for the massacre.[8] Ambrose told Theodosius to imitate David in his repentance as he had imitated him in guilt — Ambrose readmitted the emperor to the Eucharist only after several months of penance.

In the last years of Theodosius' reign, one of the emerging leaders of the Goths, named Alaric, participated in Theodosius' campaign against Eugenius in 394, only to resume his rebellious behavior against Theodosius' son and eastern successor, Arcadius, shortly after Theodosius' death.

Civil wars in the Empire

After the death of Gratian in 383, Theodosius' interests turned to the Western Roman Empire, for the usurper Magnus Maximus had taken all the provinces of the West except for Italy. This self-proclaimed threat was hostile to Theodosius' interests, since the reigning emperor Valentinian II, Maximus' enemy, was his ally. Theodosius, however, was unable to do much about Maximus due to his still inadequate military capability and he was forced to keep his attention on local matters. However when Maximus began an invasion of Italy in 387, Theodosius was forced to take action.

The armies of Theodosius and Maximus fought at the Battle of the Save in 388, which saw Maximus defeated. On 28 August 388 Maximus was executed.[9] Trouble arose again, after Valentinian was found hanging in his room. It was claimed to be a suicide by the magister militum, Arbogast.

Arbogast, unable to assume the role of Emperor because of his non-Roman background, elected Eugenius, a former teacher of rhetoric. Eugenius started a program of restoration of the Pagan faith, and sought, in vain, Theodosius' recognition. In January 393, Theodosius gave his son Honorius the full rank of "Augustus" in the West, citing Eugenius' illegitimacy.[10]

Theodosius campaigned against Eugenius. The two armies faced at the Battle of Frigidus in September 394.[11] The battle began on 5 September 394, with Theodosius' full frontal assault on Eugenius' forces. Theodosius was repulsed on the first day, and Eugenius thought the battle to be all but over. However, in Theodosius' camp, the loss of the day decreased morale. It is said that Theodosius was visited by two "heavenly riders all in white" who gave him courage. The next day, the battle began again and Theodosius' forces were aided by a natural phenomenon known as the Bora, which produces cyclonic winds. The Bora blew directly against the forces of Eugenius and disrupted the line.

Eugenius' camp was stormed, and Eugenius was captured and soon after executed. Thus Theodosius became the only emperor.

Art patronage

Theodosius oversaw the removal in 390 of an Egyptian obelisk from Alexandria to Constantinople. It is now known as the obelisk of Theodosius and still stands in the Hippodrome, the long racetrack that was the center of Constantinople's public life and scene of political turmoil. Re-erecting the monolith was a challenge for the technology that had been honed in the construction of siege engines. The obelisk, still recognizably a solar symbol, had been moved from Karnak to Alexandria with what is now the Lateran obelisk by Constantius II).

The Lateran obelisk was shipped to Rome soon afterwards, but the other one then spent a generation lying at the docks due to the difficulty involved in attempting to ship it to Constantinople. Eventually, the obelisk was cracked in transit. The white marble base is entirely covered with bas-reliefs documenting the Imperial household and the engineering feat of removing it to Constantinople. Theodosius and the Imperial family are separated from the nobles among the spectators in the Imperial box, with a cover over them as a mark of their status. The naturalism of traditional Roman art in such scenes gave way in these reliefs to conceptual art: the idea of order, decorum and respective ranking, expressed in serried ranks of faces. This is seen as evidence of formal themes beginning to oust the transitory details of mundane life, celebrated in Pagan portraiture. Christianity had only just been adopted as the new state religion.

The Forum Tauri in Constantinople was renamed and redecorated as the Forum of Theodosius, including a column and a triumphal arch in his honour.

Nicene Christianity becomes the state religion

Theodosius promoted Nicene Trinitarian Christianity within the Empire. On 27 February 380, he declared "Catholic Church" the only legitimate Imperial religion, ending official state support for the traditional religion.[12]

Nicene Creed

In 325, Constantine I facilitated the Church's bishops to convene the Council of Nicea, which affirmed the prevailing view that Jesus, the Son, was equal to the Father, one with the Father, and of the same substance (homoousios in Greek). The council condemned the teachings of the heterodox theologian Arius: that the Son was a created being and inferior to God the Father, and that the Father and Son were of a similar substance (homoiousios in Greek—a difference of one iota) but not identical (see Nontrinitarian). Despite the council's ruling, controversy continued. By the time of Theodosius' accession, there were still several different Church factions that promoted alternative Christology.

Arians

While no mainstream churchmen within the Empire explicitly adhered to Arius (a presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt) or his teachings,[dubious – discuss] there were those who still used the homoiousios formula, as well as those who attempted to bypass the debate by merely saying that Jesus was like (homoios in Greek) God the Father, without speaking of substance (ousia). All these non-Nicenes were frequently labeled as Arians (i.e., followers of Arius) by their opponents, though they would not have identified themselves as such.[13]

The Emperor Valens had favored the group who used the homoios formula; this theology was prominent in much of the East and had under the sons of Constantine the Great gained a foothold in the West. Theodosius, on the other hand, cleaved closely to the Nicene Creed which was the interpretation that predominated in the West and was held by the important Alexandrian church.

Establishment of Nicene Orthodoxy

On 27 February 380 he, together with Gratian and Valentinian II published the so called "Edict of Thessalonica" (decree "Cunctos populos", Codex Theodosianus xvi.1.2) in order that all their subjects should profess the faith of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria (i.e., the Nicene faith). The move was mainly a thrust at the various beliefs that had arisen out of Arianism, but smaller dissident sects, such as the Macedonians, were also prohibited.

On 26 November 380, two days after he had arrived in Constantinople, Theodosius expelled the non-Nicene bishop, Demophilus of Constantinople, and appointed Meletius patriarch of Antioch, and Gregory of Nazianzus, one of the Cappadocian Fathers from Antioch (today in Turkey), patriarch of Constantinople. Theodosius had just been baptized, by bishop Acholius of Thessalonica, during a severe illness, as was common in the early Christian world.

In May 381, Theodosius summoned a new ecumenical council at Constantinople (see First Council of Constantinople) to repair the schism between East and West on the basis of Nicean orthodoxy.[14] "The council went on to define orthodoxy, including the mysterious Third Person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, who, though equal to the Father, 'proceeded' from Him, whereas the Son was 'begotten' of Him."[15] The council also "condemned the Apollonarian and Macedonian heresies, clarified jurisdictions of the state church of the Roman Empire according to the civil boundaries of dioceses and ruled that Constantinople was second in precedence to Rome."[15]

The death of Valens, the Arians' protector, probably damaged the standing of the Homoian faction.

Conflicts with Pagans

Death of Western Roman Emperor Valentinian II

On 16 May 392, Valentinian II was found hanged in his residence in the town of Vienne in Gaul. The Frankish soldier and Pagan Arbogast, Valentinian's protector and magister militum, maintained that it was suicide. Arbogast and Valentinian had frequently disputed rulership over the Western Roman Empire, and Valentinian was also noted to have complained of Arbogast's control over him to Theodosius. Thus when word of his death reached Constantinople, Theodosius believed, or at least suspected, that Arbogast was lying and had engineered Valentinian's demise. These suspicions were further fueled by Arbogast's elevation of Eugenius, from pagan official, to the position of Western Emperor. Plus, Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, spoke some veiled accusations against Arbogast, in his funeral oration for Valentinian II.

Valentinian II's death sparked a civil war between Eugenius and Theodosius, over the rulership of the west, resulting in the Battle of the Frigidus. The resultant eastern victory there led to the final brief unification of the Roman Empire under Theodosius, and the ultimate irreparable division of the empire after his death.

Proscription of Paganism

The Christian persecution of paganism under Theodosius I began in 381, after the first couple of years his reign in the Eastern Roman Empire. In the 380s, Theodosius I reiterated Constantine's ban on pagan sacrifice, prohibited haruspicy on pain of death, pioneered the criminalization of Magistrates who did not enforce anti-pagan laws, broke up some pagan associations and destroyed pagan temples.

Between 389–391 he promulgated the "Theodosian decrees," which establed a practical ban on paganism;[16] visits to the temples were forbidden,[17][18] remaining pagan holidays abolished, the eternal fire in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum extinguished, the Vestal Virgins disbanded, auspices and witchcrafting punished. Theodosius refused to restore the Altar of Victory in the Senate House, as asked by pagan senators.

In 392 he became Emperor of the whole Empire (the last one to do so). From this moment till the end of his reign in 395, while pagans remained outspoken in their demands for toleration,[19][20] he authorized or participated in the destruction of many temples, holy sites, images and objects of piety throughout the Empire, [21][22][23][24][25] and participated in actions by Christians against major pagan sites.[26]

He issued a comprehensive law that prohibited any pagan ritual even within the privacy of one's home,[27] and was particularly oppressive of Manicheans.[28] Paganism was now proscribed, a "religio illicita."[29] He is likely to have suppressed the ancient Olympic Games, whose last record of celebration is from 393.[30]

Death

Theodosius died, after suffering from a disease involving severe edema, in Milan on 17 January 395. Ambrose organized and managed Theodosius's lying in state in Milan. Ambrose delivered a panegyric titled De Obitu Theodosii[31] before Stilicho and Honorius in which Ambrose detailed the suppression of heresy and paganism by Theodosius. Theodosius was finally buried in Constantinople on 8 November 395.[32]

See also

- Galla Placidia, daughter of Theodosius

- Saint Fana

- Serena, niece of Theodosius and wife of Flavius Stilicho

- Zosimus, Pagan historian from the time of Anastasius I

- Roman emperors family tree

References

- ^ In Classical Latin, Theodosius' name would be inscribed as FLAVIVS THEODOSIVS AVGVSTVS.

- ^ Cf. decree, infra.

- ^ "Edict of Thessolonica": See Codex Theodosianus XVI.1.2

- ^ See the Hydatius and Zosimus's critics and other arguments by Alicia M. Canto, «Sobre el origen bético de Teodosio I el Grande, y su improbable nacimiento en Cauca de Gallaecia», Latomus (Brussels) 65.2, 2006, págs. 388–421, cf.[1]

- ^ Zos. Historia Nova 4.24.4.

- ^ Williams and Friell, p34.

- ^ Theodoret, Ecclesiastical History

- ^ Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. 3rd edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0-14-051312-4.

- ^ Williams and Friell, p 64.

- ^ Williams and Friell, p129.

- ^ Williams and Friell, p 134.

- ^ Theodosian Code XVI.i.2, Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions

- ^ Lenski, Noel, Failure of Empire, University of California Press, 2002, ISBN 0-520-23332-8, pp235–237.

- ^ Williams and Friell, p54.

- ^ a b William and Friell, p55.

- ^ Theodosian Code 16.10.11

- ^ Routery, Michael (1997) The First Missionary War. The Church take over of the Roman Empire, Ch. 4, The Serapeum of Alexandria

- ^ Theodosian Code 16.10.10

- ^ Zosimus 4.59

- ^ Symmachus Relatio 3.

- ^ Grindle, Gilbert (1892) The Destruction of Paganism in the Roman Empire, pp.29–30. Quote summary: For example, Theodosius ordered Cynegius (Zosimus 4.37), the praetorian prefect of the East, to permanently close down the temples and forbade the worship of the deities throughout Egypt and the East. Most of the destruction was perpetrated by Christian monks and bishops,

- ^ Life of St. Martin

- ^ Gibbon, Edward The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ch28

- ^ R. MacMullen, "Christianizing The Roman Empire A.D.100–400, Yale University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-300-03642-6

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia (1912) article on Theophilus, New Advent Web Site.

- ^ Ramsay McMullan (1984) Christianizing the Roman Empire A.D. 100–400, Yale University Press, p.90.

- ^ "A History of the Church", Philip Hughes, Sheed & Ward, rev ed 1949, vol I chapter 6.

- ^ "The First Christian Theologians: An Introduction to Theology in the Early Church", Edited by Gillian Rosemary Evans, contributor Clarence Gallagher SJ, "The Imperial Ecclesiastical Lawgivers", p68, Blackwell Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-631-23187-0

- ^ Hughes, Philip Studies in Comparative Religion, The Conversion of the Roman Empire, Vol 3, CTS.

- ^ Kotynski, p.3. For more information about the question of this date, see Kotynski.

- ^ Williams and Friell, p.139.

- ^ Williams and Friell, p. 140.

Further reading

- Brown, Peter, The Rise of Western Christendom, 2003, p. 73–74

- Williams, Stephen and Gerard Friell, Theodosius: The Empire at Bay, Yale University Press, 1994.

External links

- De Imperatoribus Romanis, Theodosius I

- Josef Rist (1996). "Theodosios I., römischer Kaiser (379–395)". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 11. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 989–994. ISBN 3-88309-064-6.

- This list of Roman laws of the fourth century shows laws passed by Theodosius I relating to Christianity.