Camera obscura

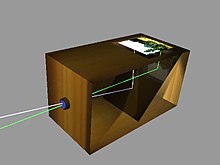

The camera obscura (Latin; camera for "vaulted chamber/room", obscura for "dark", together "darkened chamber/room"; plural: camera obscuras or camerae obscurae) is an optical device that projects an image of its surroundings on a screen. It is used in drawing and for entertainment, and was one of the inventions that led to photography and the camera. The device consists of a box or room with a hole in one side. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes a surface inside where it is reproduced, upside-down, but with color and perspective preserved. The image can be projected onto paper, and can then be traced to produce a highly accurate representation.The largest Camera obscura in the world is on Constitution Hill in Aberystwyth, Wales.[1]

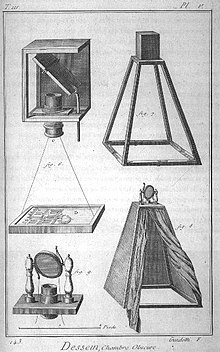

Using mirrors, as in the 18th century overhead version (illustrated in the History section below), it is possible to project a right-side-up image. Another more portable type is a box with an angled mirror projecting onto tracing paper placed on the glass top, the image being upright as viewed from the back.

As a pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but the projected image becomes dimmer. With too small a pinhole, however, the sharpness worsens, due to diffraction. Some practical camera obscuras use a lens rather than a pinhole because it allows a larger aperture, giving a usable brightness while maintaining focus. (See pinhole camera for construction information.)

History

The camera obscura has been known to scholars since the time of Mozi and Aristotle.[2] The first surviving mention of the principles behind the pinhole camera or camera obscura belongs to Mozi (Mo-Ti) (470 to 390 BCE), a Chinese philosopher and the founder of Mohism.[3] Mozi referred to this device as a "collecting plate" or "locked treasure room."[4]

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 to 322 BCE) understood the optical principle of the pinhole camera.[5] He viewed the crescent shape of a partially eclipsed sun projected on the ground through the holes in a sieve and through the gaps between the leaves of a plane tree. In the 4th century BCE, Aristotle noted that "sunlight travelling through small openings between the leaves of a tree, the holes of a sieve, the openings wickerwork, and even interlaced fingers will create circular patches of light on the ground." Euclid's Optics (ca 300 BCE) presupposed the camera obscura as a demonstration that light travels in straight lines.[6] In the 4th century, Greek scholar Theon of Alexandria observed that "candlelight passing through a pinhole will create an illuminated spot on a screen that is directly in line with the aperture and the center of the candle."

In the 6th century, Byzantine mathematician and architect Anthemius of Tralles (most famous for designing the Hagia Sophia), used a type of camera obscura in his experiments.[7]

In the 9th century, Al-Kindi (Alkindus) demonstrated that "light from the right side of the flame will pass through the aperture and end up on the left side of the screen, while light from the left side of the flame will pass through the aperture and end up on the right side of the screen."

Alhazen also gave the first clear description[8] and early analysis[9] of the camera obscura and pinhole camera. While Aristotle, Theon of Alexandria, Al-Kindi (Alkindus) and Chinese philosopher Mozi had earlier described the effects of a single light passing through a pinhole, none of them suggested that what is being projected onto the screen is an image of everything on the other side of the aperture. Alhazen was the first to demonstrate this with his lamp experiment where several different light sources are arranged across a large area. He was thus the first to successfully project an entire image from outdoors onto a screen indoors with the camera obscura.

The Song Dynasty Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) experimented with a camera obscura, and was the first to apply geometrical and quantitative attributes to it in his book of 1088 AD, the Dream Pool Essays.[10][verification needed] However, Shen Kuo alluded to the fact that the Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang written in about 840 AD by Duan Chengshi (d. 863) during the Tang Dynasty (618–907) mentioned inverting the image of a Chinese pagoda tower beside a seashore.[10] In fact, Shen makes no assertion that he was the first to experiment with such a device.[10] Shen wrote of Cheng's book: "[Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang] said that the image of the pagoda is inverted because it is beside the sea, and that the sea has that effect. This is nonsense. It is a normal principle that the image is inverted after passing through the small hole."[10]

In 13th-century England, Roger Bacon described the use of a camera obscura for the safe observation of solar eclipses.[11] Its potential as a drawing aid may have been familiar to artists by as early as the 15th century; Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519 AD) described the camera obscura in Codex Atlanticus. Johann Zahn's "Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium, which was published in 1685, contains many descriptions and diagrams, illustrations and sketches of both the camera obscura and of the magic lantern.

Giambattista della Porta is said to have perfected camera obscura described it as having a convex lens in later edition of his Magia Naturalis (1558-1589), the popularity of which helped spread knowledge of it. He compared the shape of the human eye to the lens in his camera obscura, and provided an easily understandable example of how light could bring images into the eye. One chapter in the Conte Algarotti's Saggio sopra Pittura (1764) is dedicated to the use of a camera ottica ("optic chamber") in painting.[12]

The 17th century Dutch Masters, such as Johannes Vermeer, were known for their magnificent attention to detail. It has been widely speculated that they made use of such a camera, but the extent of their use by artists at this period remains a matter of considerable controversy, recently revived by the Hockney–Falco thesis.

The term "camera obscura" itself was first used by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1604.[13] The English physician and author Sir Thomas Browne speculated upon the interrelated workings of optics and the camera obscura in his 1658 discourse The Garden of Cyrus thus:

For at the eye the Pyramidal rayes from the object, receive a decussation, and so strike a second base upon the Retina or hinder coat, the proper organ of Vision; wherein the pictures from objects are represented, answerable to the paper, or wall in the dark chamber; after the decussation of the rayes at the hole of the hornycoat, and their refraction upon the Christalline humour, answering the foramen of the window, and the convex or burning-glasses, which refract the rayes that enter it.

Early models were large; comprising either a whole darkened room or a tent (as employed by Johannes Kepler). By the 18th century, following developments by Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, more easily portable models became available. These were extensively used by amateur artists while on their travels, but they were also employed by professionals, including Paul Sandby, Canaletto and Joshua Reynolds, whose camera (disguised as a book) is now in the Science Museum (London). Such cameras were later adapted by Joseph Nicephore Niepce, Louis Daguerre and William Fox Talbot for creating the first photographs.

Gallery

-

A freestanding room-sized camera obscura at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. One of the pinholes can be seen in the panel to the left of the door.

-

A freestanding room-sized camera obscura in the shape of a camera located in San Francisco at the Cliff House in Ocean Beach

-

Image of the South Downs of Sussex as seen in the camera obscura of Foredown Tower, Portslade, England

-

A camera obscura created by Mark Ellis is built in the style of an Adirondack mountain cabin, and sits by the shore of Lake Flower in the village of Saranac Lake, NY.

-

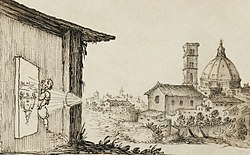

18th-century artist using a camera obscura to outline his subject

-

Image of a modern day camera obscura

-

Usage of a modern day camera obscura used indoors

See also

- Bristol Observatory

- Black mirror

- Camera

- Camera lucida

- History of cinema

- Hockney–Falco thesis

- Magic lantern

- Optics

Notes

- ^ http://www.cardiganshirecoastandcountry.com/cliff-railway-camera-obscura-aberystwyth.php Cliff Railway and Camera Obscura, Aberystwyth

- ^ Jan Campbell (2005). "Film and cinema spectatorship: melodrama and mimesis". Polity. p.114. ISBN 0-7456-2930-X

- ^ Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Page 82.

- ^ Ouellette, Jennifer. (2005). Black Bodies and Quantum Cats: Tales from the Annals of Physics. London: Penguin Books Ltd. Page 52.

- ^ Aristotle, Problems, Book XV

- ^ The Camera Obscura : Aristotle to Zahn

- ^ Crombie, Alistair Cameron (1990), Science, optics, and music in medieval and early modern thought, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 205, ISBN 978-0-907628-79-8, retrieved 22 August 2010

- ^ (Kelley, Milone & Aveni 2005):

"The first clear description of the device appears in the Book of Optics of Alhazen."

- ^ (Wade & Finger 2001):

"The principles of the camera obscura first began to be correctly analysed in the eleventh century, when they were outlined by Ibn al-Haytham."

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 98.

- ^ BBC - The Camera Obscura

- ^ Algarotti, Francesco (1764). Presso Marco Coltellini, Livorno (ed.). Saggio sopra la pittura. pp. 59–63.

- ^ History of Photography and the Camera - Part 1: The first photographs

References

- Hill, Donald R. (1993), "Islamic Science and Engineering", Edinburgh University Press, page 70.

- Lindberg, D.C. (1976), "Theories of Vision from Al Kindi to Kepler", The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

- Nazeef, Mustapha (1940), "Ibn Al-Haitham As a Naturalist Scientist", Template:Ar icon, published proceedings of the Memorial Gathering of Al-Hacan Ibn Al-Haitham, 21 December 1939, Egypt Printing.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Omar, S.B. (1977). "Ibn al-Haitham's Optics", Bibliotheca Islamica, Chicago.

- Wade, Nicholas J.; Finger, Stanley (2001), "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective", Perception, 30 (10): 1157–1177, doi:10.1068/p3210, PMID 11721819

External links

- An Appreciation of the Camera Obscura

- The Camera Obscura in San Francisco – the Giant Camera of San Francisco at Ocean Beach, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001

- Camera Obscura and World of Illusions, Edinburgh

- Dumfries Museum & Camera Obscura, Dumfries, Scotland

- Vermeer and the Camera Obscura by Philip Steadman

- Paleo-camera – the camera obscura and the origins of art

- List of all known Camera Obscura

- Willett & Patteson Camera obscura hire and creation

- Camera Obscura and Outlook Tower, Edinburgh, Scotland

- Cameraobscuras.com George T Keene builds custom camera obscuras like the Griffith Observatory CO in Los Angeles.

- Camera obscura in Trondheim, Norway, built by students of architecture and engineering from Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)

fat fat fat farts