Human skull

| Human skull | |

|---|---|

A human skull viewed from the front. | |

Human skull side bones | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cran |

| TA98 | A02.1.00.001 |

| TA2 | 406 |

| FMA | 46565 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The human skull is a bony structure, part of the skeleton, that is in the human head and which supports the structures of the face and forms a cavity for the brain.

The adult human skull is said to consist of two categorical parts of different embryological origins: The neurocranium and the viscerocranium. The neurocranium (or braincase) is a protective vault surrounding the brain and brain stem. The viscerocranium (also splanchnocranium or facial skeleton) is formed by the bones supporting the face.

Except for the mandible,[1] all of the bones of the skull are joined together by sutures, synarthrodial (immovable) joints formed by bony ossification, with Sharpey's fibres permitting some flexibility.

Structure

Bones

Various sources provide different numbers for to count of constituent bones of the human neuro- and viscerocranium. The reasons for such counting discrepancies are numerous. Different textbooks classify the bones of the human skull differently, e.g. they may (also) include (parts of) bones that are ordinarily considered neurocranial bones in their list of facial bones. Some textbooks count paired bones (where there is one bone on each side) only once instead of twice. Some sources describe the maxilla's left and right parts as two bones. Likewise, the palatine bone is also sometimes described as two bones. The hyoid bone is usually not considered part of the skull, as it does not articulate with any other bones, but some sources include it. Some sources include the ossicles, three of which on each side are encased within the temporal bones, though these are also usually not considered part of the skull. Extra sutural bones may also variably be present, but they are not counted. For all of these reasons, it may not be easy[2] to reach agreement on an authoritative bone count for the neuro- and viscerocranium and the human skull. However, such discrepancies between various sources are only differences in how to classify and/or describe the anatomy of the human skull, and regardless of what classification/description is used, the basic anatomy remains the same. With that in mind, as one possible classification, the human skull could for example be said to consist of twenty two bones: Eight bones of the neurocranium (occipital bone, 2 temporal bones, 2 parietal bones, sphenoid bone, ethmoid bone, frontal bone), and fourteen bones of the viscerocranium (vomer, 2 conchae[disambiguation needed], 2 nasal bones, 2 maxilla, mandible, 2 palatine bones, 2 zygomatic bones, 2 lacrimal bones).

The skull also contains the sinus cavities, which are air-filled cavities lined with respiratory epithelium, which also lines the large airways. The exact functions of the sinuses are debatable; they contribute to lessening the weight of the skull with a minimal reduction in strength, they contribute to resonance of the voice, and assist in the warming and moistening of air drawn in through the nasal cavity.

Foramen

The skull contains numerous openings, called foramina which allow structures such as nerves and blood vessels to enter and leave the skull.

Development

The skull is a complex structure; its bones are formed both by intramembranous and endochondral ossification. The skull roof, comprising the bones of the splanchnocranium (face) and the sides and roof of the neurocranium, is formed by intramembranous (or dermal) ossification, though the temporal bones are formed by endochondral ossification. The endocranium, the bones supporting the brain (the occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid) are largely formed by endochondral ossification. Thus frontal and parietal bones are purely membranous.[3] The geometry of the cranial base and its fossas: anterior, middle and posterior changes rapidly, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy. The first trimester is crucial for development of skull defects.[4]

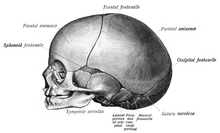

At birth, the human skull is made up of 44 separate bony elements. As growth occurs, many of these bony elements gradually fuse together into solid bone (for example, the frontal bone). The bones of the roof of the skull are initially separated by regions of dense connective tissue called "fontanels". There are six fontanels: one anterior (or frontal), one posterior (or occipital), two sphenoid (or anterolateral), and two mastoid (or posterolateral). At birth these regions are fibrous and moveable, necessary for birth and later growth. This growth can put a large amount of tension on the "obstetrical hinge", which is where the squamous and lateral parts of the occipital bone meet. A possible complication of this tension is rupture of the great cerebral vein of Galen. As growth and ossification progress, the connective tissue of the fontanelles is invaded and replaced by bone creating sutures. The five sutures are the two squamous, one coronal, one lambdoid, and one sagittal sutures. The posterior fontanel usually closes by eight weeks, but the anterior fontanel can remain open up to eighteen months. The anterior fontanel is located at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones; it is a "soft spot" on a baby's forehead. Careful observation will show that you can count a baby's heart rate by observing his or her pulse pulsing softly through the anterior fontanel.

Artificial cranial deformation is a largely historical practice of some cultures. Cords and wooden boards would be used to apply pressure to an infant's skull and alter its shape, sometimes quite significantly. This procedure would begin just after birth and would be carried on for several years.

Clinical significance

If the brain is bruised or injured it can be life-threatening. Normally the skull protects the brain from damage through its hard unyieldingness; the skull is one of the least deformable structures found in nature with it needing the force of about 1 ton[clarification needed] to reduce the diameter of the skull by 1 cm.[5] In some cases, however, of head injury, there can be raised intracranial pressure through mechanisms such as a subdural haematoma. In these cases the raised intracranial pressure can cause herniation of the brain out of the foramen magnum ("coning") because there is no space for the brain to expand; this can result in significant brain damage or death unless an urgent operation is performed to relieve the pressure. This is why patients with concussion must be watched extremely carefully.

Dating back to Neolithic times, a skull operation called trepanation was sometimes performed. This involved drilling holes in the cranium. Examination of skulls from this period reveals that the "patients" sometimes survived for many years afterward. It seems likely that trepanation was performed for ritualistic or religious reasons and not only as an attempted life-saving technique.

In March of 2013 as a world first, researchers replaced 75 percent of an injured patient's skull with a precision 3D-printed polymer replacement implant.[6]

In March of 2014, it was announced that a similar skull replacement had been performed with success on a Dutch woman three months ago.[7]

Sexual dimorphism

In the past, specifically in the mid-nineteenth century, anthropologists found it crucial to distinguish between male and female skulls. An anthropologist of the time, McGrigor Allan, argued that the female brain was similar to that of an animal.[8] This allowed anthropologists to declare that women were in fact more emotional and less like their rational male counterparts. McGrigor then concluded that women’s brains were more analogous to infants, thus deeming them inferior at the time.[9] To further these claims of female inferiority and silence the feminists of the time, other anthropologists joined in on the studies of the female skull. These cranial measurements are the basis of what is known as craniology. These cranial measurements were also used to draw a connection between women and black people. French craniologist, F. Pruner, went on to describe this relationship as: “The Negro resemble[ing] the female in his love for children, his family, and his cabin".[9] Pruner also went on to say that the negro is what the female is to the white man, “a loving being and a being of pleasure”.[9] New forms of cranial measurement continued to progress well into the early twentieth century in an effort to further implement the sexual dimorphism between male and female skulls.

Research today shows that while in early life there is little difference between male and female skulls, in adulthood male skulls tend to be larger and more robust than female skulls, which are lighter and smaller, with a cranial capacity about 10 percent less than that of the male.[10] However, new studies show that women's skulls are thicker and thus men may be more susceptible to head injury than women.[11][12] It has been claimed that the larger male brain is an effect of having larger body size, and that after correction, the difference disappears. This is not the case. Before correction males average about 130 g3 more brain matter, this is reduced to about 100 g3 after correction for body size.[13] Some authors consider this size difference to partly explain the alleged difference in average intelligence between men and women, and between various human races.[13][14]

Male skulls can have more prominent supraorbital ridges, a more prominent glabella, and more prominent temporal lines. Female skulls generally have rounder orbits, and narrower jaws. Male skulls on average have larger, broader palates, squarer orbits, larger mastoid processes, larger sinuses, and larger occipital condyles than those of females. Male mandibles typically have squarer chins and thicker, rougher muscle attachments than female mandibles. Surgical alteration of sexually dimorphic skull features may be carried out as a part of Facial feminization surgery, a set of reconstructive surgical that can alter male facial features to bring them closer in shape and size to typical female facial features.[15][16] These procedures can be an important part of the treatment of transgender women for gender dysphoria.[17][18]

Society and culture

Phrenology

Like the face of a living individual, a human skull and teeth can also tell, to a certain degree, the life history and origin of its owner. Forensic scientists and archaeologists use metric and nonmetric traits to estimate what the bearer of the skull looked like. When a significant amount of bones are found, such as at Spitalfields in the UK and Jōmon shell mounds in Japan, osteologists can use traits, such as the proportions of length, height and width, to know the relationships of the population of the study with other living or extinct populations.

The German physician Franz Joseph Gall in around 1800 formulated the theory of phrenology, which attempted to show that specific features of the skull are associated with certain personality traits or intellectual capabilities of its owner. His theory is now considered to be pseudoscientific. However, despite the pseudoscientific beginnings it is now well established that cranium size and brain size does correlate with IQ, at 0.20 and 0.40 respectively. The correlation with psychometric intelligence is even higher at 0.63.[13]

Additional images

-

The lower inner surface of the neurocranium

-

A cross-section of a skull by Leonardo da Vinci

-

Male human skull

-

Child viscerocranium

-

Anterior, middle and posterior fossa

-

Bones of human skull

-

Endobasis-resistances beams

-

Endobasis-resistances nodes

-

The lower inner surface of the neurocranium- 11 weeks' fertilization age

See also

- Base of the skull, a detailed list of the anatomical structures found at the base of the skull

- Craniometry

- Head and neck anatomy

- Obstetrical dilemma

- Phrenology, the pseudoscientific process of determining personality from the shape of the head

- Plagiocephaly, the abnormal flattening of one side of the skull

- Human skull symbolism

- Crystal skull (disambiguation)

- Yorick

- Memento mori

References

- ^ and the hyoid bone, though this is not usually considered part of the skull

- ^ or even very useful

- ^ Carlson, Bruce M. (1999). Human Embryology & Developmental Biology. Mosby. pp. 166–170. ISBN 0-8151-1458-3.

- ^ Derkowski, Wojciech; Kędzia, Alicja; Glonek, Michał (2003). "Clinical anatomy of the human anterior cranial fossa during the prenatal period". Folia morphologica. 62 (3): 271–3. PMID 14507064.

- ^ Holbourn, A. H. S. (1943). MECHANICS OF HEAD INJURIES. The Lancet, 242: (6267), 438-441. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)87453-X

- ^ "3D-Printed Polymer Skull Implant Used For First Time in US". Medicaldaily.com. 7 March 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Dutch hospital gives patient new plastic skull, made by 3D printer". Dutchnews.dl. 26 March 2014.

- ^ Fee, Elizabeth (1979). Nineteenth-Century Craniology: The Study of the Female Skull. pp. 415–473.

- ^ a b c Fee, Elizabeth (1979). Nineteenth-Century Craniology: The Study of the Female Skull. pp. 415–453.

- ^ "The Interior of the Skull". Gray's Anatomy. Retrieved 2010-111-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Men May Be More Susceptible To Head Injury Than Women, Study Suggests". Science Daily. Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- ^ Li, Ruan, Xie, and Wang (2007). "Investigation of the critical geometric characteristics of living human skulls utilising medical image analysis techniques". International Journal of Vehicle Safety. 2 (4): 345–367. doi:10.1504/IJVS.2007.016747.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Rushton, J. Philippe (1 January 2009). "Whole Brain Size and General Mental Ability: A Review". International Journal of Neuroscience. 119 (5): 692–732. doi:10.1080/00207450802325843. PMC 2668913. PMID 19283594.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rushton, J. Philippe (1 January 2005). "Thirty years of research on race differences in cognitive ability". Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 11 (2): 235–294. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.11.2.235.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ainsworth, TA; Spiegel, JH (2010). "Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery". Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 19 (7): 1019–24. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9668-7. PMID 20461468.

- ^ Shams, MG; Motamedi, MH (2009). "Case report: Feminizing the male face". Eplasty. 9: e2. PMC 2627308. PMID 19198644.

- ^ World Professional Association for Transgender Health. WPATH Clarification on Medical Necessity of Treatment, Sex Reassignment, and Insurance Coverage in the U.S.A. (2008).

- ^ World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Version 7. pg. 58 (2011).

- White, T.D. 1991. Human osteology. Academic Press, Inc. San Diego, CA.

External links

- [1](human skull base with very detailed labelling in German)

- Human Skulls / Anthropological Skulls / Comparison of Skulls of Vertebrates (PDF; 502 kB)