Talk:Abiogenesis

| This article is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abiogenesis received a peer review by Wikipedia editors, which is now archived. It may contain ideas you can use to improve this article. |

There have been attempts to recruit editors of specific viewpoints to this article, in a manner that does not comply with Wikipedia's policies. Editors are encouraged to use neutral mechanisms for requesting outside input (e.g. a "request for comment", a third opinion or other noticeboard post, or neutral criteria: "pinging all editors who have edited this page in the last 48 hours"). If someone has asked you to provide your opinion here, examine the arguments, not the editors who have made them. Reminder: disputes are resolved by consensus, not by majority vote. |

|

Much of the content of Abiogenesis was merged from Origin of life. For discussion of that page preceding that merge, see here. |

|

This page has archives. Sections older than 90 days may be automatically archived by Lowercase sigmabot III when more than 1 section is present. |

Regarding the Spoken Version

At the time I made this recording in February, this article was, and still is, completely in-accessible to laymen. I explained or canned the ridiculously technical aspects and got to the point of them as well as the tedious repitition and the self-serving name-dropping of the source of various studies used throughout. This is an encyclopedia, not Google Scholar. I didn't alter the actual text of the article.

- Not sure who wrote the above, nor when. Sorry. GeorgeLouis (talk) 21:08, 9 February 2014 (UTC)

Horrible Introduction!

I rolled my eyes at the awful, incorrect and irrelevant first paragraph of the introduction: "Abiogenesis ... or biopoiesis is a natural process by which life arises from simple organic compounds." There is NO defined process, at best we have frameworks. Hiding the fact that this subject is deeply speculative is deceptive. Who claims that abiogenesis must start with simple organic molecules? It is just not true. Astronomical sources of complex organic molecules, for example, may have existed long before they fell to Earth to be converted into living systems (or precursors thereof).

Abiogenesis is the term used to describe the hypothetical chemical processes that led to life on Earth. A multitude of scenarios have been proposed and there is little agreement because evidence is virtually non existent.

"The earliest life on Earth existed at least 3.5 billion years ago,[6][7][8] during the Eoarchean Era when sufficient crust had solidified following the molten Hadean Eon." What has this second sentence to do with the core issue? Little as far as I can see. It is a thought fragment, probably a remnant of the edit wars. It disrupts the narrative and should, imho, be removed.

The Miller-Urey experiment is flawed because the assumed conditions (reducting) are no longer most consistent with the geological evidence, right? It is interesting for historical reasons, but since it is no longer plausible, imho, it shouldn't be mentioned in the Introduction.

- Recent studies with an updated understanding of the early Earth environment have again shown spontaneous generation of amino acids and carbohydrates. For example, see http://www.bio.miami.edu/dana/dox/Cleaves2008.pdf. Kkosman (talk) 17:18, 9 January 2014 (UTC)

Why not simply describe the complexity of the issue, and the multiple avenues approaching the evolution of a homeostatic catalytic chemical reaction system? Beyond a certain point, a cell of membrane is necessary. Self-catalysis is also necessary absent a natural catalytic substrate. And self-replication is also necessary. None of these things can independently lead to life as we know it. So why not just lay it out. Maybe start with the definition of life, and how it is believed early systems developed the structures to conform to that definition. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 216.96.76.228 (talk) 01:25, 6 September 2013 (UTC)

- The present Introductory sentences seem well-sourced and appropriate - specifying a particular "definition of life" has been a challenge; several definitions are noted at the following => Life#Definitions - there's been several (somewhat lengthy) discussions, including the following => Talk:Life/Archive_4#Definition_of_Life_2 - perhaps some suggested well-sourced introductory sentences would be helpful? - in any case - Enjoy! :) Drbogdan (talk) 04:02, 6 September 2013 (UTC)

- The Miller-Urey experiment was a chemistry experiment (duplicated by the way), not a geology experiment. Yes, aminos don't last long in an earth environment, but it's far more plausuble than the theory that all of the amino acids that we need for life on Earth all come from a few meteors.

- What's remarkable, is that prebiotics (aminos etc.) somehow developed in the conditions of space in much less favorable conditions than the Miller-Urey experiment.

- Was there once a former planet with these compounds? Is that why they are in space? Kortoso (talk) 20:12, 11 September 2013 (UTC)

- No, they were actually formed in space by chemical reactions, aided by the action of stellar radiation, between atoms of hydrogen (mostly from the Big Bang) and other elements created in earlier stars by nucleogenesis and scattered in supernovas. This process was/is very slow by terrestrial standards because of the low densities and temperatures of such "clouds" of atoms and molecules, but it's been going on for some 13 billion years. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195 212.95.237.92 (talk) 18:50, 6 November 2013 (UTC)

- Was there once a former planet with these compounds? Is that why they are in space? Kortoso (talk) 20:12, 11 September 2013 (UTC)

- The opening sentence scopes abiogenesis to *natural* accounts. While this page deals with scientific, and therefore natural accounts, does the word 'abiogenesis' outside of the context of this page mean exclusively natural accounts, or is it more generally a formal word for the origin of life by any processes, natural or supernatural? Matthew Pocock (talk) 20:40, 12 March 2014 (UTC)

- "Abiogenesis" refers to life initiating through natural means only, and or the study of how and what possible/potential ways life initiated through natural means. Life initiating through supernatural means would be various forms of Creationism believe.--Mr Fink (talk) 21:38, 12 March 2014 (UTC)

- Fine. I was under the impression that 'abiogenesis' was a catch-all term for 'life initiating', although obviously supernatural means don't fall within science. Matthew Pocock (talk) 20:12, 17 March 2014 (UTC)

- Look at the ethymology of abiogenesis: a (not) + bios (life) + genesis (emergence) ≈ emergence from non-life. BatteryIncluded (talk) 00:05, 20 March 2014 (UTC)

- Fine. I was under the impression that 'abiogenesis' was a catch-all term for 'life initiating', although obviously supernatural means don't fall within science. Matthew Pocock (talk) 20:12, 17 March 2014 (UTC)

- "Abiogenesis" refers to life initiating through natural means only, and or the study of how and what possible/potential ways life initiated through natural means. Life initiating through supernatural means would be various forms of Creationism believe.--Mr Fink (talk) 21:38, 12 March 2014 (UTC)

Imprecise terminology

Not sure there's a better way to say this, but in the primordial soup section, there's a bit that says "synthesized organic compounds from inorganic precursors". Thing is... by at least some definitions, anything that contains carbon (or, at least, carbon and hydrogen) is "organic". So technically that statement is incorrect. By definition, unless you have some nuclear fission or fusion going on, you can only make organic compounds from organic precursors... Tamtrible (talk) 20:44, 17 October 2013 (UTC)

- Carbon dioxide is often considered to be inorganic, since many rocks are carbonates. From that viewpoint, the formation of urea from ammonium carbonate counts as the creation of an organic compound from an inorganic precursor. Howard Landman (talk) 21:42, 19 January 2014 (UTC)

The article's first sentence is perhaps incorrect

The first sentence reads, "Abiogenesis or biopoiesis is a natural process by which life arises from simple organic compounds."

This is being stated as a fact; however, is there PROOF that abiogenesis has ever occurred as a "natural" process? Or is it mere speculation and a leap of faith? Unless this is a known fact, and not an assumption, why is this being stated as a fact in a scientific article? Later on, we find this information:

Professor Colin S. Pittendrigh stated in December 1967 that "laboratories will be creating a living cell within ten years,"

That was almost half a century ago when he made that prediction. He was obviously wrong. So exactly what scientific criteria are being used to make the article's opening statement? Dontreader (talk) 19:39, 31 October 2013 (UTC)

- It would, perhaps, be a tiny bit more accurate to add "thought to be", "considered to be", "believed to be" or "defined as" after the "is". The last of that list would, I think, be the most neutral. Tamtrible (talk) 22:13, 31 October 2013 (UTC)

- Those are excellent suggestions, Tamtrible. Thanks for taking the time to ponder the situation. I agree that a modification (such as one of your suggestions) should be included after the "is", as you indicated. Thanks again. Dontreader (talk) 23:54, 31 October 2013 (UTC)

- Already done. Tamtrible (talk) 18:20, 1 November 2013 (UTC)

- Thanks, Tamtrible. That looked great to me, but your edit has been changed back to the original form. I have written a message on the talk page of the user who made the subsequent edit, asking him/her to come here. Thanks again. Dontreader (talk) 21:17, 2 November 2013 (UTC)

- I made that change because in Wikipedia articles, terms are generally defined as their subjects. That is, articles generally don't say "term is defined as...", articles just say "term is...". This is a style convention, not a content convention. A completely fictional subject is still introduced this way. • If your concern is you want the content to reflect the lack of proof, I would suggest treating that directly. For example, like this. That's how most of the dictionaries I spot checked seemed to handle it. —DragonHawk (talk|hist) 20:01, 3 November 2013 (UTC)

- Thanks DragonHawk for coming here and for your very clear explanation; I also appreciate your research on the issue and I hope your edit will be kept since it sure looks like a solid scientific solution. The way the sentence was written when I first read the article was philosophically flawed. Thanks again. Dontreader (talk) 21:21, 3 November 2013 (UTC)

- Please see the talk page archives for previous discussion on this issue. :-) Briefly, while there are many hypotheses about various stages in the process of abiogenesis, the existence of the process itself is factual. Arc (talk) 08:44, 13 November 2013 (UTC)

- I think there is... a legitimate issue here. Entirely aside from any notion of special creation or whatever, there is the possibility that life on Earth was seeded from another planet. Admittedly, this would just mean that abiogenesis happened somewhere else (possibly in deep space or something), but this article is mainly discussing the various theories and hypotheses of how abiogenesis occurred *on Earth*. And, of course, there's always the possibility, however remote, that something wildly different from anything we would recognize as abiogenesis is what actually occurred. Would you be happier with "theory" rather than "hypothesis"? Tamtrible (talk) 20:30, 14 November 2013 (UTC)

- The use of "theory" has been discussed as well, actually. For myself, I think a reasonable argument can be made for it, if it's appropriately wikilinked, but the consensus from the last time around was to treat it as a fact instead. I favor this view as well. With respect to panspermia, the definition doesn't speak to that; abiogenesis may have occurred elsewhere, but it still remains the same process.

- Further comments (not relevant to any definitional questions): I agree that in some places the article does use prose that assumes an Earth origin when not strictly necessary, and this could be fixed. The current coverage of the topic may not be as bad as you think, though - e.g. see the sections here and here, or run searches for "space," "panspermia," etc. I’m also working on some changes to the article that will probably make these sections more prominent - a mention in the lead might not be out of place either. However, Earth origin is the most commonly discussed by the available high-quality research, so the article's focus still needs to reflect that (WP:DUE). Arc (talk) 10:45, 15 November 2013 (UTC)

- It might not be entirely inappropriate, at the *bottom* of the article, to have a short section, saying something like:

- Alternatives to abiogenesis

- The possibility exists that the first organic life on Earth did not spontaneously arise, or arrive from space by chance, but instead was in some fashion deliberately created and/or placed here. However, this raises the problem of where that deliberate creator came from. If it was an organic life form of some kind, or a product or device originally made by same, that merely pushes the question of abiogenesis back to that life form's place of origin. If it was not an organic life form, directly or indirectly, then it is necessary to explain how something other than organic life, that was not created by organic life, is capable of deliberate action. No such intelligence is presently known to exist. If it was a divine being, then in a meaningful sense the question falls outside the scope of science, though if said being did so in a manner that could also have happened by chance, then it can be treated equivalently.

- Or something like that. Someone else can probably phrase it more elegantly. Tamtrible (talk) 19:11, 15 November 2013 (UTC)

- It might not be entirely inappropriate, at the *bottom* of the article, to have a short section, saying something like:

- In the first part of your suggestion, you're talking about directed panspermia. :-) This isn't about the abiogenic process per se (rather it is a specific hypothesis about how life might spread between planets), but it does have some relevance so it could be mentioned. However, the second part of your suggestion ("If it was not...equivalently") is outside the scope of this article, which is about scientific views (see the hatnote at the top of the page). It may be more appropriate in another article, such as Creation myth, but be aware that you would still need reliable sources to cite your statements. Arc (talk) 21:10, 16 November 2013 (UTC)

- Actually, I'm mentioning the remote scientific possibility that organic life was artificially generated by nonorganic life of some sort. For example, crystalline silicon life forms. Something like that would, of necessity, have a different type of origin than organic life, so would not simply move abiogenesis as discussed in the rest of the article to a different origin point. *Then* I mentioned the possibility of divine creation, and essentially said "But that's outside the scope of this article". Tamtrible (talk) 07:52, 18 November 2013 (UTC)

- Yes, that specific point (the possibility of generation of organic life by inorganic life) would definitely be within the scope of the article, so it could be included if it were substantiated. Like I said above, you would need reliable sources, and for this example I would also invoke WP:EXCEPTIONAL. I know that speculation about inorganic life can be supported (for example, see Hypothetical types of biochemistry) but the sources would need to specifically make the connection that you're suggesting. Arc (talk) 08:53, 19 November 2013 (UTC)

- How would you feel about a header like "Unlikely and/or non-scientific alternatives", with text something like:

- Directed panspermia, or life planted on Earth deliberately by some kind of extraterrestrial intelligence, would simply move the process of abiogenesis to an extraterrestrial origin point. If organic life was intentionally created by some sort of intelligent inorganic life form (link here to the hypothetical biochemistry article), this would not require any form of undirected abiogenesis as discussed here, as presumably life forms with wildly different biochemistry would have different origins, but no such life forms are known to exist at present. Discussion of any form of divine creation (link to creation myths page) is outside the scope of this article.

- Or something like that. Would that be acceptable without sources? Tamtrible (talk) 17:38, 19 November 2013 (UTC)

- You are missing the point. Wikipedia is not the place to publish original thinking on a subject. You need to find a quality source of any such claim you want to add to this article. Wikipedia isn't designed to synthesize new points of view. In other words: No, it wouldn't be acceptable. See my new section on article revision, however.Abitslow (talk) 17:48, 20 November 2013 (UTC)

- Hello Arc. You wrote, "while there are many hypotheses about various stages in the process of abiogenesis, the existence of the process itself is factual." Well, by definition, abiogenesis is indeed a process by which life arises from non-living matter; however, the article reads that it's a "natural" process. There is no proof that abiogenesis is a natural process, which is why I prefer "hypothetical natural process". And specifically on Earth, the existence of the process itself being "natural" is not factual. Instead, it's an assumption, a leap of faith, and that's not a scientific approach.

- You are missing the point. Wikipedia is not the place to publish original thinking on a subject. You need to find a quality source of any such claim you want to add to this article. Wikipedia isn't designed to synthesize new points of view. In other words: No, it wouldn't be acceptable. See my new section on article revision, however.Abitslow (talk) 17:48, 20 November 2013 (UTC)

- How would you feel about a header like "Unlikely and/or non-scientific alternatives", with text something like:

- Here's the mistake: we know that there is life on Earth, and we know that there was a time when there was no life on Earth, so we know that at some point life appeared on Earth. But some people have assumed that at some point life arose on Earth "naturally". That's a flawed argument unless you call it a hypothesis. Maybe life arose on Earth naturally, but from a philosophical point of view there are endless possibilities. What if God created the earliest life forms on Earth? The concept of God seems irrational to us but philosophically it's a possibility. Or many gods. Or angels. Or what if advanced extraterrestrials came to Earth and brought primitive life forms with them? Even some scientists believe that perhaps life on Earth originated in outer space. So, life on Earth did not necessarily arise as the consequence of a natural process on Earth. In fact, when you think about it, one could argue that the apparition of life from a lifeless environment is as absurd as the existence of a god. My point is that I believe that if we are to call abiogenesis a "natural" process, it should be called a "hypothetical natural process". Thanks for your time. Dontreader (talk) 09:55, 28 November 2013 (UTC)

- I think it's perfectly reasonable to leave off the "hypothetical", *if* we at least briefly discuss, later in the article, possible alternatives--directed panspermia (which either moves the abiogenesis question to another world, or requires life forms sufficiently different from us, such as crystals or cloud-like energy beings, that abiogenesis as discussed in the article would be irrelevant) and special creation (which is a nonscientific approach, so mention of that would just lead to a link to the relevant page and a mention that it's outside the scope of the article). Basically, butt-covering of "If it's not a natural process that happened by some means on Earth, this is what it might have been instead."--at the end of the article, where it won't get in the way. Tamtrible (talk) 06:14, 29 November 2013 (UTC)

- Thanks Tamtrible. I'm fine with what you proposed. After all, the assertion that abiogenesis is a "natural" process is merely an assumption, not a proven fact, so that's not the way a scientific article should be written, unless there's a fix somewhere, as you explained. At least there is certainly empirical evidence that evolution has taken place (like the fossil record and DNA analyses), but what I see in the first sentence of this article is a giant leap of faith. Thanks again and have a nice day. Dontreader (talk) 21:58, 29 November 2013 (UTC)

Since we seem to agree that a new section would resolve those concerns, why don't we work on making a proposal for that section? (I know one has been made already, but see the comments on needing reliable sources.) My only additional comment at the moment is that the hatnote at the top of the article is probably sufficient to define the article's scope - it is better style to avoid terms like "this article." Dontreader, you may also want to read my above conversation with Tamtrible. :-) Arc (talk) 00:52, 30 November 2013 (UTC)

- Hello again, Arc, and thanks for your thoughts; I had already read your discussion above with Tamtrible, and I addressed you recently there. I understand that you are apparently disappointed that this topic has surfaced once more, but I believe the previous consensus is flawed, and there are multiple problems; for example, at the top of the article we find the following:

- "Origin of life" redirects here. For non-scientific views on the origins of life, see Creation myth.

- In other words, if a reader searches for "Origin of life", he or she is automatically brought to this article, as if it were a fact that the scientific approach on the origin of life is the true one, even though there is no evidence for this; again, it is a mere assumption, and the inference is that the "Creation myth" article contains purely savage and puerile notions, when in reality it is hypothetically conceivable that (for example) a god created life directly and in a supernatural manner. I don't understand how that note at the top of the article appeared. Wikipedians who are militant atheists? Wikipedians who are proud scientists like Professor Colin S. Pittendrigh, who turned out to be a fool because of his senseless prediction? Look, the creation stories have many ridiculous elements, but there could be some degree of truth in them. We must be cautious. If "Origin of life" redirects here to explain the true origin of life, we must give readers the truth, and the truth is that science is not sure, so indeed a section is needed to address that problem, and I am certainly willing to help.

- Also, Arc de Ciel, in the discussion, you stated: "the existence of the process itself is factual." But where is the proof? Every attempt at creating life from a lifeless environment has failed dismally. Even the most primitive conceivable life forms are incredibly complex, so I'm not in the least bit surprised. Am I to understand that you assume that one day a scientific team will finally succeed? As you know, assumptions are not facts, and therefore please explain why the existence of abiogenesis is factual (let alone "natural").

- Finally, the first paragraph in the article provides the meaning of "abiogenesis" and then very cleverly implies that it took place on Earth, so that readers will believe that abiogenesis actually took place on Earth; again, it's not stated, only implied, but that should be fixed, I think. The second paragraph does refer to abiogenesis on Earth as an assumption, which is better.

- For the record, I was agnostic for some time but then I became a firm believer in God; however, I have a scientific background, and my religious views are regarded as extremely heretical. Thanks for your time. Dontreader (talk) 22:32, 30 November 2013 (UTC)

- As someone who has a scientific background, you should realize that the scientific method always assumes that everything has a natural cause, and that this is one of the fundamental aspects of scientific research. After all, if it's not natural, it can't be observed, can't be studied, and can't be disproven. The existence of abiogenesis is absolutely 100% fact, because if it didn't exist, there wouldn't be any life. Wikipedia leans towards science on topics that science studies because science backs itself up with evidence and changes views with new discoveries, something that almost never happens with creation myths. Ego White Tray (talk) 00:16, 1 December 2013 (UTC)

- Thanks, Ego White Tray. Indeed, the scientific method always assumes that everything has a natural cause, and that's the way it should be. Wouldn't you agree that the scientific method has been applied to abiogenesis many times? If so, the results have been utterly disastrous. Would you say that scientists are closer now than 50 years ago to creating life from a lifeless environment? If not, how many hundreds of years and experiments must be conducted before the assumption is questioned? Or are you 100% convinced that some day abiogenesis will finally take place in a laboratory if mankind lives on long enough? Because that could only be the stance of an atheist. Even Isaac Newton reached a point when he abandoned the assumption that everything had a natural cause, after careful consideration. Yet Newton challenged very methodically the religious beliefs he was raised with. The main point is this: even though the scientific method always assumes that everything has a natural cause, that does not necessarily mean that everything has a natural cause, and therefore the existence of abiogenesis is not necessarily a fact.

- We need philosophers here, in my opinion, because there appears to be a deadlock. For example, if I propose that the concept of God is irrational to human beings because we are but mere close relatives of chimpanzees, and therefore the intelligence of human beings is minuscule, where am I going wrong? What if the concept of God makes sense to an alien civilization that is intellectually a million times superior to us? The scientific community should be more humble. Besides, does ANYONE seriously believe that even the most primitive conceivable life forms - given their enormous complexity - can show up in a laboratory from a lifeless environment? Let some philosophers come here and be given the minimum requirements for the existence of a life form (by consensus) and see what they tell us. Thanks again. Dontreader (talk) 10:01, 2 December 2013 (UTC)

- Abiogenesis is a scientific topic, so philosophers are not needed for it, and nature must suffice. If you can't agree with it, you're not really on-board with this whole science thing. The reason that life has not been generated in a lab is simple - it's extremely difficult to do. Modern scientists don't have millions of years for their experiments to work (which was probably the case in nature billions of years ago), and modern scientists need to fight the oxygen that's everywhere, and most importantly, the life that's everywhere that will eat anything they create. Just because scientists haven't succeeded yet, doesn't mean it isn't true - the opposite conclusion is a favorite of creationists and other pseudo-science arguments. Ego White Tray (talk) 15:30, 2 December 2013 (UTC)

- Ego White Tray, philosophy and science are not mutually exclusive, but after pondering the situation, I think it might not be viable to include philosophers in this discussion unless they are familiar with this field of science to some degree. I just would like to see more people with different backgrounds here. How can you say that I'm "not really on-board with this whole science thing."? Are you an atheist? Who can deny that Isaac Newton had one of the most brilliant scientific minds in history? Are you not aware of the fact that he approached religion with the same analytical thinking as he did with science, yet he remained a believer in God? He ended up with heretical views on Christianity, yet he remained a believer in God, and he did not believe that everything had a natural cause. Therefore, would you state that Newton was "not really on-board with this whole science thing."?

- You also wrote, "The reason that life has not been generated in a lab is simple - it's extremely difficult to do." That is certainly not what Colin Pittendrigh thought, given his regrettable prediction. You have also stated that "The existence of abiogenesis is absolutely 100% fact", which is false. The flawed reasoning you provided for this assertion is not that of rigorous science; instead, it looks more like the reasoning of an atheist. Evolution, for example, has vast empirical evidence, but there is zero evidence or proof that abiogenesis has ever taken place; therefore, to claim that it is absolutely 100% fact is not scientific. Hence, I still believe that abiogenesis should be called a hypothetical process, lest we make leaps of faith not dissimilar to those of religious fundamentalists. Dontreader (talk) 21:17, 2 December 2013 (UTC)

- Please stop bringing up religion; it's not relevant to this article. (Especially not speculation on the religion of editors or lack thereof.) Likewise, I don't see the relevance of Pittendrigh or Newton - I don't see any way to relate either of them to this discussion that does not involve a logical fallacy of some sort (appeal to authority, anecdotal fallacy, etc).

- Anyways: a failure to completely describe the process (thus far) does not indicate a lack of progress. In fact, a lot of the progress that has been made is described in the article. One of the more important pieces of evidence is the discovery that all the functions of metabolism and heredity can be carried out by a single type of macromolecule (RNA), which shows the plausibility of life forms much simpler than the simplest which exist today. So the simplest answer to your question, "Would you say that scientists are closer now than 50 years ago to creating life from a lifeless environment?" - is yes. But the question is misdirected, because "creating life" is not the proximal goal - rather it is to understand the steps which abiogenesis may have involved. I can cite any number of research papers (or you can look at the ones in the article) that are studying these steps and contributing to our understanding. Arc (talk) 02:45, 3 December 2013 (UTC)

- Arc, I brought up Newton and religion again because I perceived that an attempt was made to disqualify me as a contributor to the discussion. If I'm "not really on-board with this whole science thing", then neither was Newton. Anyway, even if the first life forms were much simpler than the simplest which exist today, abiogenesis still has catastrophic problems. Life is an all-or-nothing situation. By definition, the concept of abiogenesis requires a living entity to directly descend from a non-living entity, or at least to be created from a lifeless environment. You said progress has been made; that's good news because the Miller–Urey experiment - although interesting - was a total failure, unless the goal was to merely create amino acids. Wouldn't you agree that even the simplest conceivable living organisms need a protein molecule? If so, how many amino acids found in the Miller–Urey experiment were linked together in a manner that got close to resembling a protein molecule? Or have more successful subsequent experiments properly produced linked amino acids that nearly reached protein molecule status? Let alone the RNA macromolecule which you mentioned, which I assume has a genetic code for vital functions, including viable reproduction. And what about some sort of a cell membrane? Don't you need all of these things, if not more? That's why I question the real progress that has been made. I truly do believe that abiogenesis is hypothetically possible, and it should be called a hypothetical process. Dontreader (talk) 03:45, 4 December 2013 (UTC)

- Life is only an "all-or nothing situation" in the definitional sense. The line could have been drawn elsewhere; viruses, viroids and prions are all made of the same type of molecules but are simpler. They exhibit some of the typical characteristics of life but not others - e.g. these groups are all subject to natural selection, meaning that they can increase in complexity given enough generations. "Life descending from non-life" is an oversimplification, because of the very large gray area in between the two categories. The earliest replicator could have been as simple as a polymerase chain reaction (and there is research which suggests this as a possibility).

- "Wouldn't you agree that even the simplest conceivable living organisms need a protein molecule?" Nope - see my comment about RNA. A cell membrane is not a prerequisite for life either (and certainly not a prerequisite for a primitive replicator), although it is possible that the first life did have cell membranes. Arc (talk) 05:57, 4 December 2013 (UTC)

- Thanks Arc for your observations; however, you are relying merely on hypotheses. For example, has a life form without protein molecules ever been found in nature or produced in a laboratory? I don't think so. Every possibility you wrote is hypothetical (correct me if I'm wrong), and therefore I don't understand why you are so opposed to calling abiogenesis a hypothetical process. Then, whenever it's actually proven to be factual, you could take out "hypothetical" from the article again. Please, what exactly is your problem with that? Dontreader (talk) 10:15, 4 December 2013 (UTC)

- What reliable source supports describing abiogenesis as a "hypothetical process"? Is evolution a hypothetical process? A hypothesis is something like "life may have started by process A then B then C" (where A, B and C are described in some detail). A different source may say "no, it was probably X then Y then Z". There would then be two hypotheses waiting for evidence. However, abiogenesis itself is not hypothetical—it is the natural process by which life arose, with many details as yet unknown. If a reliable source says that there is no such natural process, we can add relevant information to the article. Please do not ping other editors unless they have asked. Johnuniq (talk) 10:57, 4 December 2013 (UTC)

- Thanks Arc for your observations; however, you are relying merely on hypotheses. For example, has a life form without protein molecules ever been found in nature or produced in a laboratory? I don't think so. Every possibility you wrote is hypothetical (correct me if I'm wrong), and therefore I don't understand why you are so opposed to calling abiogenesis a hypothetical process. Then, whenever it's actually proven to be factual, you could take out "hypothetical" from the article again. Please, what exactly is your problem with that? Dontreader (talk) 10:15, 4 December 2013 (UTC)

So. Anyways. I think at least most of us can agree that abiogenesis should be treated as, in essence, scientific fact about which we do not entirely understand the details, but that at least brief mention of alternatives to abiogenesis happening on Earth or otherwise "naturally" occurring (directed panspermia, creation by nonorganic life forms, possibly essentially unscientific alternatives such as special creation) should be made. At least, that's my read on the above discussion. So, any cogent proposals on how to phrase said brief mention? — Preceding unsigned comment added by Tamtrible (talk • contribs) 16:20, 4 December 2013 (UTC)

- Just one caveat. :-) I don't think the article necessarily suffers from lacking such a mention - rather I have said that such a mention would be within the scope of the article (other than special creation, of course) if appropriate sources could be found. A couple of my previous comments: [1] [2]. I think directed panspermia probably has such sources but creation by nonorganic life forms probably does not. But either way it would depend on which sources are brought forward. Arc (talk) 02:55, 5 December 2013 (UTC)

- I was pinging other editors just to try to make sure that they noticed my replies. Can someone please explain to me what's wrong with doing so? I would have responded much sooner if someone had pinged me. Anyway, I have read with great interest these newest entries, and whatever you decide to do is fine with me. I'm just sincerely trying to improve the article, but if my arguments are regarded as flawed, at least I have tried my best. This is my final attempt to make my case. Johnuniq was correct until he stated that "abiogenesis itself is not hypothetical—it is the natural process by which life arose, with many details as yet unknown." Unlike evolutionary theory, which has plenty of empirical evidence, there is no scientific evidence for abiogensesis as a natural process. ZERO. Therefore, from a scientific point of view, abiogenesis is NOT a fact; instead, it's a hypothesis or a theory. Johnuniq asked for a reliable source, so how about this one?

- "biopoiesis, a process by which living organisms are thought to develop from nonliving matter, and the basis of a theory on the origin of life on Earth. According to this theory, conditions were such that, at one time in Earth’s history, life was created from nonliving material, probably in the sea, which contained the necessary chemicals. During this process, molecules slowly grouped, then regrouped, forming ever more efficient means for energy transformation and becoming capable of reproduction."

- Isn't that encyclopedia a reliable source?

- Interestingly, the Spanish version of Wikipedia calls it a theory, the German version calls it a hypothesis, the French version merely states that abiogenesis is "the study of the generation of life from non-living matter." (and cites astronomer Fred Hoyle), and the Italian version calls it a theory. Yet somehow English-speaking Wikipedians know that abiogenesis is a fact. Dontreader (talk) 01:29, 7 December 2013 (UTC)

- Only all sources outside of Wikipedia call it a hypothesis. In fact all the sources Wikipedia uses calls it an hypothesis too. "Yet somehow English-speaking Wikipedians know that abiogenesis is a fact. " no, just the atheists who religiously defend this article. --Suigens (talk) 07:11, 9 January 2014 (UTC)

- I think this article needs to be reevaluated somewhat. --200.198.252.200 (talk) 5:58 pm, Today (UTC−5)

I'm going to side with those who want to see the word "hypothesis" or similar wording. Even though it has slowly gotten more and more plausible over the last century, abiogenesis is still very far from proven. I would also oppose using the word "theory" because it generally implies (in science) a much more well-tested explanation. Even a positive demonstration of life forming in vitro would still leave the origin of life on earth question open, as it wouldn't rule out some form of panspermia. Howard Landman (talk) 09:52, 20 January 2014 (UTC)

- I wouldn't say current research has shown it to be plausible. Unfortunately it seems anyone disagreeing with the hypothesis is automatically labelled as a creationist by the trolls here (even though creationism, and indeed, the creationism-evolution controversy, is a totally different and unrelated subject). Apparently the bias of some Wikipedians don't want to mention some of the stuff that biologists are saying in regards to abiogenesis. "Nobody understands the origin of life. If they say they do, they are probably trying to fool you." ~ Ken Nealson PhD, 2002 Robert Roy Britt, "The Search for the Scum of the Universe," http://www.panspermia.org/rnaworld.htm# Then there's Andrew Knoll, a respected biology professor who says that he "doesn't know" if the mystery will ever be solved. How Did Life Begin? NOVA and Andrew H. Knoll PhD, Havard University. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/evolution/how-did-life-begin.html But apparently it's factual to Wikipedia even though it's all speculation and hypothetical to scientists at the moment (and quite possibly forever more) as those sources reveal. --Diskain (talk) 18:11, 12 March 2014 (UTC)

- Everything developed from energy and stardust from the Bing Bang, so abiogenesis is a fact. I have no problem calling abiogenesis on Earth a hypothesis, because even if speculation is entertained to give context, abiogenesis concerns itself primarily with hypotheses that fit firmly into existing scientific theories and on the physicochemical laws of the universe. I do however, disagree to insert the word "hypothesis" as an excuse to sneak "goddidit" as an equally valid and rigorous hypothesis. --BatteryIncluded (talk) 01:37, 20 March 2014 (UTC)

- The Big Bang concerns the origin of the universe, not the origin of life and is a theory in physics not in biology. I can only deduct from this that you don't understand the theories and hypothesizes that you preach about. Abiogenesis is not a fact then, as The Big Bang theory is something completely different and doesn't even connect to the abiogenesis hypothesis. Indeed, some scientists saw religious implications in the theory which led some (such as Fred Hoyle) to reject it http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Bang#Development. The Big Bang is fact. Abiogenesis isn't. --86.21.101.169 (talk) 13:28, 27 March 2014 (UTC)

Article needs rewritten introduction and structural revision.

I agree that the Intro is rotten. Way too much of it is about Miller-Urey and the large volume of discredited work (much good work, but bad assumptions about atmospheric composition). Someone needs to find a better definition of abiogenesis. "Spontaneous" should, in my personal opinion, be part of definition in order to distinguish abiogenesis from designed (or created) life origins. The Miller-Urey work was/is significant for several reasons and needs to be (imho) part of the lede, but not its details. Panspermia is given short shrift. The subject, abiogenesis, is concerned with the where, when and how of the origin of life, starting with commonly abundant chemical building blocks (mostly but not totally organic) and showing that a spontaneous mechanism exists, given possible physical and chemical conditions, for life to develop. It is not logically valid to claim that the goal of the research is to determine "the" mechanism for the origin of life on Earth, but such demonstrations will (if ever accomplished) have a significant impact (imho) on many philosophical and religious questions. Avoiding the philosophical seems a bit misleading/blind. the lede should be an overview of the field, and then concentrate on accomplishments in specific areas, I think. Surely 'experts' have published on these points somewhere! Anybody researched Dirk Schulze-Makuch's work? Non-equilibrium thermodynamics is barely mentioned in the article, yet a recent article in American Scientist pointed out its relevance, as did (if I recall, it was so long ago) Prigogine's classic book. And the fountain of work on Complex Systems of the last 2 decades seems to be unknown here. ???Abitslow (talk) 18:18, 20 November 2013 (UTC)

In regards to abiogenesis being an hypothesis

| thread is not supposed to be a soapbox nor a forum thread for inserting inappropriate non-neutral point of view |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

|

The "reliable" sources weren't stating abiogenesis as factual. Indeed the own Wikipedia page on here suggests Panspermia afterwards due to the problems of abiogenesis. The sources were from Alexander Oparin, Scientific American (arguing for Panspermia rather than abiogenesis), the other (life from RNA world) is the RNA world hypothesis. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RNA_world_hypothesis Let's stop with the lying then shall we and actually check the sources next time. --Suigens (talk) 07:25, 9 January 2014 (UTC)

|

Abiogenesis is a hypothesis not a fact nor a theory

| thread is not supposed to be a soapbox nor a forum thread for inserting inappropriate non-neutral point of view |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

|

"Abiogenesis (/ˌeɪbaɪ.ɵˈdʒɛnɨsɪs/ ay-by-oh-jen-ə-siss) or biopoiesis is the natural process by which life arose from non-living matter such as simple organic compounds." This is incorrect. It should really say that abiogenesis is an hypothesis fueled on speculation hypothesizing the natural process of how life might have arose from non-living matter. The introduction is therefore dishonest in trying to assert abiogenesis as an undeniable fact. --86.21.101.169 (talk) 17:52, 8 January 2014 (UTC)

|

lede: arise, arose?

It has been a discussion quite a while ago (initiated by me, because I changed arose to arise). If abiogenesis is in the past, it is a historic science. Never to be repeated, never to be proven. If it is an experimental science, the verb should be in the present tense, because it could happen again (if not on earth than on another planet, or in deep space). I will change the verb into the present tense. Northfox (talk) 12:54, 18 January 2014 (UTC)

- according to Vsmith, who reverted my edit, abiogenesis is a one-in-a-universe event that happened in the past, once and for all. Never to be repeated, and thus never to be proven. Then, why not completely change the article to reflect that line of thought? Northfox (talk) 14:00, 18 January 2014 (UTC)

- (ec)What tense do the four sources use? If the sources are using past tense, then why change it? I've restored "arose". Doesn't say "never to be repeated" ... and what does "proven" have to do with anything here? Yes, it seems logical that life could "arise" elsewhere, but that is rather speculative until we have evidence - from Mars perhaps (but again that happening/evidence is likely past tense also). Vsmith (talk) 14:09, 18 January 2014 (UTC)

- And says nothing 'bout "one-in-a-universe event". Just that we only have one well studied sample. Vsmith (talk) 14:09, 18 January 2014 (UTC)

- There is a difference between abiogenesis in general (first sentence in lede) and abiogenesis on earth (second sentence). First sentence: abiogenesis is a process. It should not depend on place and time (e.g. 'water boils at 100°C under ambient pressure' is in present tense). If abiogenesis is THE only conceivable natural process by which life arises, it should be in the present tense. If in the past tense, it indicates a once-in-a-universe-lifetime event, and thus not repeatable, (and I assume thus thus not provable). Second sentence: Life on earth arose in the past, and there is evidence for a single progenitor organism. Thus, in the second sentence of the lede, past tense is okay.Northfox (talk) 10:19, 19 January 2014 (UTC)

- maybe let me try to explain by using a simple example. Let's say somebody was successful in producing life from non-life. He then would not be allowed to use the word 'abiogenesis' for his finding, because according to wikipedia, abiogenesis is the process by which life arose. I think, abiogenesis is either a general process, and then in present tense, or a special process once in the past here on earth in the past tense, but then 'on earth' should be added to the first sentence of the lede. Northfox (talk) 10:56, 19 January 2014 (UTC)

- ...would not be allowed to use the word 'abiogenesis'... ...because according to wikipedia... - now that's funny. When such happens - and after the ensuing debate settles down - then we can report such and worry 'bout a couple of words. Vsmith (talk) 13:44, 19 January 2014 (UTC)

- Vsmith, my funny example was written tongue in cheek. But more seriously, please consider the use of present tense for other natural processes. Osmosis, photosynthesis, apoptosis, pyrolysis, endocytosis, all are defined in the present tense in wikipedia. 'Once-in-a-universe' events like Big Bang nucleosynthesis (the ending -sis indicates a process) in the past perfect tense. Once-in-an-earth events (not really a process, by the way) like the Cambrian explosion in the past tense. I strongly feel that a past tense 'abiogenesis' restricts it to a past event, which, like the Cambrian explosion, can neither be repeated, nor proven by experiment. 'Abiogenesis was' means that it does not happen anymore, and it will not happen anymore. The past tense makes it inaccessible to experiment. Who can be so sure? Northfox (talk) 14:33, 19 January 2014 (UTC)

- ...would not be allowed to use the word 'abiogenesis'... ...because according to wikipedia... - now that's funny. When such happens - and after the ensuing debate settles down - then we can report such and worry 'bout a couple of words. Vsmith (talk) 13:44, 19 January 2014 (UTC)

- And says nothing 'bout "one-in-a-universe event". Just that we only have one well studied sample. Vsmith (talk) 14:09, 18 January 2014 (UTC)

To reiterate Northfox's point, we have to distinguish the historical question ("How did life arise on planet Earth?") from the plausibility question ("Is it possible for life to arise from non-life, and if so how?"). Abiogenesis covers both of these, but they have very different statuses, since we will almost certainly never have a definitive answer to the first (most of the evidence has been destroyed), while it is easy to believe that we might get a definitive answer to the second someday. Maybe the article needs to distinguish them more clearly. Or maybe we need two different articles. Howard Landman (talk) 03:18, 20 January 2014 (UTC)

- Seems the article is about the origin of life on Earth and doesn't address abiogenesis in other contexts. Perhaps you would like a "new" article on philosophical or modern abiogenesis. However, maybe first view the history of this article and the decision back in 2008 to rename Origin of life to abiogenesis - and the long talk page discussions back then. Should you decide to add something re: life arising from non-life in a non-historical context, well - bring along some WP:RS's discussing such and start a new proposal section here. Vsmith (talk) 14:25, 20 January 2014 (UTC)

FWIW - seems to me atm the abiogenesis article is about the orgin of life generally - and not only about life on Earth exclusively - nevertheless, the only confirmed instance, so far, of the existence of life is on Earth - and much, but not all, of the abiogenesis article presumes life may have begun on Earth - however, other possibilities - such as panspermia, coenzyme world and others are also considered - which to me atm seems *entirely* ok - and consistent with recent evidences suggesting that starting materials for life may be present throughout the universe - and not just solely on planet Earth - (my NYT comment - related link - may be somewhat relevant) - (should note that viable earthly life-forms transported to extraterrestrial areas via forward contamination and/or directed panspermia may extend the scope of the abiogenesis article as well I would think) - in any case - presenting the origin of life in a general way in the abiogenesis article seems *entirely* ok with me atm - Enjoy! :) Drbogdan (talk) 15:38, 20 January 2014 (UTC)

Chirality section needs updating.

The section on chirality is very out of date. There has been a lot of progress in the last 20-25 years, and none of it appears here. A good survey is given in The Origin of Biological Homochirality by Donna G. Blackmond. As can be seen from that paper, even to just cover the main results in 1 sentence each might require expanding the Chirality section to 5 or 10 times its current size. I might be willing to tackle this myself if there is general approval that it should be done, but it's a lot of work. Howard Landman (talk) 21:52, 19 January 2014 (UTC)

- It is an important subject, but should be as brief as is consonant with clarity.Rick Norwood (talk) 14:06, 20 January 2014 (UTC)

Origin of life in hot mineral water as part of Deep sea vent hypothesis

- I was published in Further reading 5 publications with links from the authors with proofs for origin of life in hot or hot mineral water and thermal energy. There are – Sugawara et all., Pons et all., Ward, Ignatov and Mosin, Shock with model for Mars. For me the life is in different types, which are depending of water. I need support from other editors. --Analiticus (talk) 19:58, 25 January 2014 (UTC)

- My proposed text for the origination of life in hot mineral water similar as Deep see vent hypothesis also contains current publications from December 2013. All stated authors have scientific publications in journals of high impact factor. --Analiticus (talk) 10:07, 13 February 2014 (UTC)

Source list

Hi everyone (this is Arc, for those who aren't aware). I've compiled a list of sources (Talk:Abiogenesis/Sources) that I'm intending to use as a basis to make some major improvements to the article. I tend to work slowly though (I started on this ~6 months ago), so I'm posting it for anyone who would like to join in. Sunrise (talk) 07:33, 6 March 2014 (UTC)

- Dear Sunrise, thank you very much for your professional edition of Abiogenesis.

--Analiticus (talk) 10:25, 14 March 2014 (UTC)

Deletionists, Unite!

| thread is not supposed to be a soapbox nor a forum thread |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

|

Just curious as to why the first (afaik) human created life from chemical building blocks (with citations and sources!) is not acceptable in this article. Your move wikipedians.

|

Planning

I just thought I would write this up to give editors a general idea of my thoughts and plans at the moment. This will also function as an approximate to-do list.

- Continuing to add content from the source list (of course). My focus thus far has mostly been on Origin of organic molecules and RNA world - I decided not to get into Protocells right away but it will probably also be a focus soon. I also haven't started adding content from some of the most useful general reviews.

- A lot of the article is based on primary sources. At some point I'll probably start moving some of them to a subpage so that if there's any useful content it won't be lost.

- Adjusting relative weight of topics based on the representation in secondary sources, per WP:DUE. (I was surprised to find that metabolism-first hypotheses are actually not well-represented in this regard.)

- Some further reorganization. Thus far I've mainly made changes for the topics I've been working on, and I've approximately followed the layout of some of the general reviews. I think "Other models" will eventually be broken up, like I did for "Current models."

- Small things - edits for coherency and clarity, etc. I also have a document with notes on more specialized topics that might or might not make it into the final product.

Of course, everything is subject to change and the feedback of other editors. :-) Sunrise (talk) 05:40, 15 March 2014 (UTC)

- Dear Sunrise, accept my congratulation for your plan. I am professor of physics

and your edition is with deep understanding of science, the methods in the science, reliable sources and excellent logic for the structuring of the text. --Analiticus (talk) 06:12, 15 March 2014 (UTC)

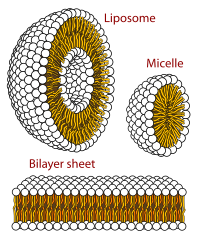

- I support the suggestion to expand the protocell subsection, and cover the micelle → protocell → living cell model. I'll take a look at it on Monday. I will have some more feedback after reading the whole article, reviewing its sources, and the Talk page history. Cheers, BatteryIncluded (talk) 23:58, 16 March 2014 (UTC)

Here below I am pasting a draft o what would become a new article: Protocell. I meant to write only a section for the abiogenesis article but grew into what it is now. I would use only a portion of it here and link the main article to "protocell'. Please feel free to review and modify it at will before I make it go live. Thanks, --BatteryIncluded (talk) 20:05, 18 March 2014 (UTC)

| Large draft on protocells for your review. |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

A protocell is self-organized, endogenously ordered, spherical collection of lipids proposed as a stepping-stone to the origin of life.[1] A central question in evolution is how simple protocells first arose and began the competitive process that drove the evolution of life. Although a functional protocell has not yet been achieved in a laboratory setting, the goal appears well within reach.[2][3][4] Selectivity for a boundarySelf-assembled vesicles are essential components of primitive cells.[1] The second law of thermodynamics requires that the universe move in a direction in which disorder (or entropy) increases, yet life is distinguished by its great degree of organization. Therefore, a boundary is needed to separate life processes from non-living matter.[5] The cell membrane is the only cellular structure that is found in all of the cells of all of the organisms on Earth.[6] Reseachers Irene A. Chen and Jack W. Szostak (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2009) amongst others, demonstrated that simple physicochemical properties of elementary protocells can give rise to essential cellular behaviors, including primitive forms of Darwinian competition and energy storage. Such cooperative interactions between the membrane and encapsulated contents could greatly simplify the transition from replicating molecules to true cells.[3] Furthermore, competition for membrane molecules would favor stabilized membranes, suggesting a selective advantage for the evolution of cross-linked fatty acids and even the phospholipids of today.[3] This micro-encapsulation allowed for metabolism within the membrane, exchange of small molecules and prevention of passage of large substances across it.[7] The main advantages of encapsulation include increased solubility of the cargo and creating energy in the form of chemical gradient. Energy is thus often said to be stored by cells in the structures of molecules of substances such as carbohydrates (including sugars), lipids, and proteins, which release energy when reacted with oxygen in respiration.[8][9] Energy gradientA March 2014 study by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, demonstrated a unique way to study the origins of life: fuel cells.[10] Fuel cells are similar to biological cells in that electrons are also transferred to and from molecules. In both cases, this results in electricity and power. The study states that one important factor was that the Earth provides electrical energy at the seafloor. "This energy could have kick-started life and could have sustained life after it arose. Now, we have a way of testing different materials and environments that could have helped life arise not just on Earth, but possibly on Mars, Europa and other places in the Solar System."[10] Vesicles and micelles When phospholipids are placed in water, the molecules spontaneously arrange such that the tails are shielded from the water, resulting in the formation of membrane structures such as bilayers, vesicles, and micelles. In modern cells, vesicles are involved in metabolism, transport, buoyancy control,[11] and enzyme storage. They can also act as natural chemical reaction chambers. A typical vesicle or micelle in aqueous solution forms an aggregate with the hydrophilic "head" regions in contact with surrounding solvent, sequestering the hydrophobic single-tail regions in the micelle centre. This phase is caused by the packing behavior of single-tail lipids in a bilayer. Although the protocellular self-assembly process that spontaneously form lipid monolayer vesicles and micelles in nature resemble the kinds of primordial vesicles or protocells that might have existed at the beginning of evolution, they are not as sophisticated as the bilayer membranes of today's living organisms.Cite error: The Rather than being made up of phospholipids, however, early membranes may have formed from monolayers or bilayers of fatty acids, which may have formed more readily in a prebiotic environment.[12] Fatty acids have been synthesized in laboratories under a variety of prebiotic conditions and have been found on meteorites, suggesting their natural synthesis in nature.[3] Geothermal ponds and clay Scientists have come to conclude that life began in hydrothermal vents in the deep sea, but a 2012 study led by Armen Mulkidjanian of Germany's University of Osnabrück, suggests that inland pools of condensed and cooled geothermal vapour have the ideal characteristics for the origin of life.[13] The conclusion is based mainly on the chemistry of modern cells, where the cytoplasm is rich in potassium, zinc, manganese, and phosphate ions, which are not widespread in marine environments. Such conditions, the researchers argue, are found only where hot hydrothermal fluid brings the ions to the surface — places such as geysers, mud pots, fumeroles and other geothermal features. Within these fuming and bubbling basins, water laden with zinc and manganese ions could have collected, cooled and condensed in shallow pools.[13] In the 1990s biochemist James Ferris of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute showed that montmorillonite clay can help create RNA chains of as many as 50 nucleotides joined together spontaneously into a single RNA molecule.[4] Then in 2002, Hanczyc, Fujikawa and Szostak discovered that by adding montmorillonite to their solution of fatty acid micelles (lipid spheres), the clay sped up the rate of vesicles formation 100-fold.[4] So this one mineral that can get precursors (nucleotides) to spontaneously assemble into RNA and membrane precursors to assemble into membrane. Research has shown that some minerals can catalyze the stepwise formation of hydrocarbon tails of fatty acids from hydrogen and carbon monoxide gases - gases that may have been released from hydrothermal vents or geysers. Fatty acids of various lengths are eventually released into the surrounding water,[12] but vesicle formation requires a higher concentration of fatty acids, so it is suggested that that protocell formation started at land-bound hydrothermal vents such as geysers, mud pots, fumeroles and other geothermal features where water evaporates and concentrates the solute.[4][14][15] Montmorillonite bubblesA team of applied physicists at Harvard's School of Engineering and Applied Sciences say that primitive cells might have formed inside inorganic clay microcompartments, which can provide an ideal container for the synthesis and compartmentalization of complex organic molecules.[16] Clay-armored "bubbles" form naturally when particles of montmorillonite clay collect on the outer surface of air bubbles under water. This creates a semipermeable vesicle from materials that are readily available in the environment. The authors remark that montmorillonite is known to serve as a chemical catalyst, encouraging lipids to form membranes and single nucleotides to join into strands of RNA. Primitive reproduction can be envisioned when the clay bubbles burst, releasing the lipid membrane-bound product into the surrounding medium.[16] Membrane transport Instead of the more popular phospholipids of modern cells, the membrane of protocells in the RNA world would be composed of fatty acids,[17] and that such membranes have relatively high permeability to ions and small molecules,[1] such as nucleoside monophosphate (NMP), nucleoside diphosphate (NDP), and nucleoside triphosphatee (NTP), and may withstand millimolar concentrations of Mg2+.[18] Osmotic pressure also plays a significant role in protocell membrane transport.[1] It has been proposed that electroporation resulting from lightning strikes could be a mechanism of natural horizontal gene transfer.[19] Electroporation is the rapid increase in bilayer permeability induced by the application of a large artificial electric field across the membrane. During electroporation in laboratory procedures, the lipid molecules are not chemically altered but simply shift position, opening up a pore (hole) that acts as the conductive pathway through the bilayer as it is filled with water. The mechanism is the creation of nanometer sized water-filled holes in the membrane. Experimentally, electroporation is used to introduce hydrophilic molecules into cells. It is a particularly useful technique for large highly charged molecules such as DNA and RNA, which would never passively diffuse across the hydrophobic bilayer core.[20] Because of this, electroporation is one of the key methods of transfection as well as bacterial transformation.

Some molecules or particles are too large or too hydrophilic to pass through a lipid bilayer, but can be moved across the cell membrane through fusion or budding of vesicles.[21] This may have eventually led to mechanisms that facilitate movement of molecules to the inside (endocytosis) or to release its contents into the extracellular space (exocytosis). Endosymbiotic theory The endosymbiotic theory states that several key organelles of eukaryotes originated as symbioses between separate single-celled organisms. According to this theory, mitochondria,[22][23] chloroplasts,[24] and possibly other organelles, represent formerly free-living bacteria that were taken inside another cell as an endosymbiont. As evidence, the mitochondrion has its own independent mitochondrial DNA genome. Further, its DNA shows substantial similarity to bacterial genomes,[25] particularly, molecular and biochemical evidence suggest that the mitochondrion developed from proteobacteria.[26][27] The mitochondrion (plural mitochondria) is a membrane-bound organelle found in most eukaryotic cells (the cells that make up plants, animals, fungi, and many other forms of life).[28] A mitochondrion produces adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and it is closely related to the adenosine nucleotide, a monomer of RNA. ATP is often called the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer.[29] ATP transports chemical energy within cells for metabolism. ATP is one of the end products of photophosphorylation, cellular respiration, and fermentation and used by enzymes and structural proteins in many cellular processes, including biosynthetic reactions, motility, and cell division.[30] See alsoReferences

External links

[[Category:Evolutionarily significant biological phenomena]] [[Category:Evolutionary biology]] [[Category:Origin of life]] [[Category:Membrane biology]] |

- Awesome! :-) Nothing jumps out at me as a problem on my first read-through. I'll go through in more detail later as well. Sunrise (talk) 04:42, 20 March 2014 (UTC)

Early Conditions and Boiling Point

I am not an advanced scientist; however, I do not appreciate the cursory treatment of early oceans forming in temperature conditions at the boiling point of water. Better corroboration is needed to support this claim (full citation is EUR 39), and to make the rest of the article readable. This simple avoidance of pedestrian explanation closes the mind to any other productive idea in this article. Editorially, my mind calls question to the claim.

- Dear, there are two reports for the early conditions of water - temperature, content of deuterium, etc.

- Journal of Environment and Earth Sciences, impact factor 5.56:

http://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEES/article/view/9903 Modeling of Possible Processes for Origin of Life and Living Matter in Hot Mineral and Seawater with Deuterium Ignat Ignatov, Oleg Mosin

- Biology Direct, impact factor 2.72

http://www.biologydirect.com/content/4/1/26 On the origin of life in the Zinc world: 1. Photosynthesizing, porous edifices built of hydrothermally precipitated zinc sulfide as cradles of life on Earth Armen Y Mulkidjanian --Analiticus (talk) 06:38, 16 March 2014 (UTC)

- B-Class Evolutionary biology articles

- High-importance Evolutionary biology articles

- WikiProject Evolutionary biology articles

- B-Class Biology articles

- High-importance Biology articles

- WikiProject Biology articles

- B-Class Palaeontology articles

- High-importance Palaeontology articles

- High-importance B-Class Palaeontology articles

- WikiProject Palaeontology articles

- B-Class Geology articles

- High-importance Geology articles

- High-importance B-Class Geology articles

- WikiProject Geology articles

- Old requests for peer review

- Wikipedia controversial topics