Behaalotecha

Behaalotecha, Beha’alotecha, Beha’alothekha, or Behaaloscha (Template:Hebrew — Hebrew for "when you step up,” the 11th word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 36th weekly Torah portion (Template:Hebrew, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the third in the book of Numbers. It constitutes Numbers 8:1–12:16. The parashah is made up of 7,055 Hebrew letters, 1,840 Hebrew words, and 136 verses, and can occupy about 240 lines in a Torah Scroll (Template:Hebrew, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews generally read it in late May or in June. As the parashah sets out some of the laws of Passover, Jews also read part of the parashah, Numbers 9:1–14, as the initial Torah reading for the fourth intermediate day (Template:Hebrew, Chol HaMoed) of Passover.

The parashah tells of the lampstand in the Tabernacle, the consecration of the Levites, the Second Passover, how a cloud and fire led the Israelites, the silver trumpets, how the Israelites set out on their journeys, complaining by the Israelites, and how Miriam and Aaron questioned Moses.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or Template:Hebrew, aliyot.[2]

First reading — Numbers 8:1–14

In the first reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), God told Moses to tell Aaron to mount the seven lamps so as to give light to the front of the lampstand in the Tabernacle, and Aaron did so.[3] God told Moses to cleanse the Levites by sprinkling on them water of purification, and making them shave their whole bodies and wash their clothes.[4] Moses was to assemble the Israelites around the Levites and cause the Israelites to lay their hands upon the Levites.[5] Aaron was to designate the Levites as an elevation offering from the Israelites.[6] The Levites were then to lay their hands in turn upon the heads of two bulls, one as a sin offering and the other as a burnt offering, to make expiation for the Levites.[7]

Second reading — Numbers 8:15–26

In the second reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), the Levites were qualified for the service of the Tent of Meeting, in place of the firstborn of the Israelites.[8] God told Moses that Levites aged 25 to 50 were to work in the service of the Tent of Meeting, but after age 50 they were to retire and could stand guard but not perform labor.[9]

Third reading — Numbers 9:1–14

In the third reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), at the beginning of the second year following the Exodus from Egypt, God told Moses to have the Israelites celebrate Passover at its set time.[10] But some men were unclean because they had had contact with a corpse and could not offer the Passover sacrifice on the set day.[11] They asked Moses and Aaron how they could participate in Passover, and Moses told them to stand by while he listened for God’s instructions.[12] God told Moses that whenever Israelites were defiled by a corpse or on a long journey on Passover, they were to offer the Passover offering on the 14th day of the second month — a month after Passover — otherwise in strict accord with the law of the Passover sacrifice.[13] But if a man who was clean and not on a journey refrained from offering the Passover sacrifice, he was to be cut off from his kin.[14]

Fourth reading — Numbers 9:15–10:10

In the fourth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), starting the day that the Tabernacle was set up, a cloud covered the Tabernacle by day, and a fire rested on it by night.[15] Whenever the cloud lifted from the Tent, the Israelites would follow it until the cloud settled, and there the Israelites would make camp and stay as long as the cloud lingered.[16] God told Moses to have two silver trumpets made to summon the community and to set it in motion.[17] Upon long blasts of the two horns, the whole community was to assemble before the entrance of the Tent of Meeting.[18] Upon the blast of one, the chieftains were to assemble.[19] Short blasts directed the divisions encamped on the east to move forward, and a second set of short blasts directed those on the south to move forward.[20] As well, short blasts were to be sounded when the Israelites were at war against an aggressor who attacked them, and the trumpets were to be sounded on joyous occasions, Festivals, new moons, burnt offerings, and sacrifices of well-being.[21]

Fifth reading — Numbers 10:11–34

In the fifth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), in the second month of the second year, the cloud lifted from the Tabernacle and the Israelites set out on their journeys from the wilderness of Sinai to the wilderness of Paran.[22] Moses asked his father-in-law (here called Hobab son of Reuel the Midianite) to come with the Israelites, promising to be generous with him, but he replied that he would return to his native land.[23] Moses pressed him again, noting that he could serve as the Israelites’ guide.[24] They marched three days distance from Mount Sinai, with the Ark of the Covenant in front of them, and God’s cloud above them by day.[25]

Sixth reading — Numbers 10:35–11:29

In the sixth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), when the Ark was to set out, Moses would say: “Advance, O Lord! May Your enemies be scattered, and may Your foes flee before You!”[26] And when it halted, he would say: “Return, O Lord, You who are Israel’s myriads of thousands!”[27] The people took to complaining bitterly before God, and God ravaged the outskirts of the camp with fire until Moses prayed to God, and then the fire died down.[28] The riffraff in their midst (Template:Hebrew, asafsuf — compare the “mixed multitude,” Template:Hebrew, erev rav of Exodus 12:38) felt a gluttonous craving and the Israelites complained, “If only we had meat to eat![29] Moses in turn complained to God, “Why have You . . . laid the burden of all this people upon me?[30] God told Moses to gather 70 elders, so that God could come down and put some of the spirit that rested on Moses upon them, so that they might share the burden of the people.[31] And God told Moses to tell the people to purify themselves, for the next day they would eat meat.[32] But Moses questioned how enough flocks, herds, or fish could be found to feed 600,000.[33] God answered: “Is there a limit to the Lord’s power?”[34] Moses gathered the 70 elders, and God came down in a cloud, spoke to Moses, and drew upon the spirit that was on Moses and put it upon the elders.[35] When the spirit rested upon them, they spoke in ecstasy, but did not continue.[36] Eldad and Medad had remained in camp, yet the spirit rested upon them, and they spoke in ecstasy in the camp.[37] When a youth reported to Moses that Eldad and Medad were acting the prophet in the camp, Joshua called on Moses to restrain them.[38] But Moses told Joshua: “Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets, that the Lord put His spirit upon them!”[39]

Seventh reading — Numbers 11:30–12:16

In the seventh reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), a wind from God then swept quail from the sea and strewed them all around the camp, and the people gathered quail for two days.[40] While the meat was still between their teeth, God struck the people with a plague.[41] Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses, saying: “He married a Cushite woman!” and “Has the Lord spoken only through Moses? Has He not spoken through us as well?”[42] God heard and called Moses, Aaron, and Miriam to come to the Tent of Meeting.[43] God came down in cloud and called out to Aaron and Miriam: “When a prophet of the Lord arises among you, I make Myself known to him in a vision, I speak with him in a dream. Not so with My servant Moses; he is trusted throughout My household. With him I speak mouth to mouth, plainly and not in riddles, and he beholds the likeness of the Lord. How then did you not shrink from speaking against My servant Moses!”[44] As the cloud withdrew, Miriam was stricken with snow-white scales.[45] Moses cried out to God, “O God, pray heal her!”[46] But God said to Moses, “If her father spat in her face, would she not bear her shame for seven days? Let her be shut out of camp for seven days.”[47] And the people waited until she rejoined the camp.[48]

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[49]

Numbers chapter 8

This is the pattern of instruction and construction of the Tabernacle and its furnishings:

| Item | Instruction | Construction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Verses | Order | Verses | |

| The Sabbath | 16 | Exodus 31:12–17 | 1 | Exodus 35:1–3 |

| Contributions | 1 | Exodus 25:1–9 | 2 | Exodus 35:4–29 |

| Craftspeople | 15 | Exodus 31:1–11 | 3 | Exodus 35:30–36:7 |

| Tabernacle | 5 | Exodus 26:1–37 | 4 | Exodus 36:8–38 |

| Ark | 2 | Exodus 25:10–22 | 5 | Exodus 37:1–9 |

| Table | 3 | Exodus 25:23–30 | 6 | Exodus 37:10–16 |

| Menorah | 4 | Exodus 25:31–40 | 7 | Exodus 37:17–24 |

| Altar of Incense | 11 | Exodus 30:1–10 | 8 | Exodus 37:25–28 |

| Anointing Oil | 13 | Exodus 30:22–33 | 9 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Incense | 14 | Exodus 30:34–38 | 10 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Altar of Sacrifice | 6 | Exodus 27:1–8 | 11 | Exodus 38:1–7 |

| Laver | 12 | Exodus 30:17–21 | 12 | Exodus 38:8 |

| Tabernacle Court | 7 | Exodus 27:9–19 | 13 | Exodus 38:9–20 |

| Priestly Garments | 9 | Exodus 28:1–43 | 14 | Exodus 39:1–31 |

| Ordination Ritual | 10 | Exodus 29:1–46 | 15 | Leviticus 8:1–9:24 |

| Lamp | 8 | Exodus 27:20–21 | 16 | Numbers 8:1–4 |

Numbers chapter 9

Passover

Numbers 9:1–14 refers to the Festival of Passover. In the Hebrew Bible, Passover is called:

- “Passover” (Template:Hebrew, Pesach);[50]

- “The Feast of Unleavened Bread” (Template:Hebrew, Chag haMatzot);[51] and

- “A holy convocation” or “a solemn assembly” (Template:Hebrew, mikrah kodesh).[52]

Some explain the double nomenclature of “Passover” and “Feast of Unleavened Bread” as referring to two separate feasts that the Israelites combined sometime between the Exodus and when the Biblical text became settled.[53] Exodus 34:18–20 and Deuteronomy 15:19–16:8 indicate that the dedication of the firstborn also became associated with the festival.

Some believe that the “Feast of Unleavened Bread” was an agricultural festival at which the Israelites celebrated the beginning of the grain harvest. Moses may have had this festival in mind when in Exodus 5:1 and 10:9 he petitioned Pharaoh to let the Israelites go to celebrate a feast in the wilderness.[54]

“Passover,” on the other hand, was associated with a thanksgiving sacrifice of a lamb, also called “the Passover,” “the Passover lamb,” or “the Passover offering.”[55]

Exodus 12:5–6, Leviticus 23:5, and Numbers 9:3 and 5, and 28:16 direct “Passover” to take place on the evening of the fourteenth of Template:Hebrew, Aviv (Template:Hebrew, Nisan in the Hebrew calendar after the Babylonian captivity). Joshua 5:10, Ezekiel 45:21, Ezra 6:19, and 2 Chronicles 35:1 confirm that practice. Exodus 12:18–19, 23:15, and 34:18, Leviticus 23:6, and Ezekiel 45:21 direct the “Feast of Unleavened Bread” to take place over seven days and Leviticus 23:6 and Ezekiel 45:21 direct that it begin on the fifteenth of the month. Some believe that the propinquity of the dates of the two Festivals led to their confusion and merger.[56]

Exodus 12:23 and 27 link the word “Passover” (Template:Hebrew, Pesach) to God’s act to “pass over” (Template:Hebrew, pasach) the Israelites’ houses in the plague of the firstborn. In the Torah, the consolidated Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread thus commemorate the Israelites’ liberation from Egypt.[57]

The Hebrew Bible frequently notes the Israelites’ observance of Passover at turning points in their history. Numbers 9:1–5 reports God’s direction to the Israelites to observe Passover in the wilderness of Sinai on the anniversary of their liberation from Egypt. Joshua 5:10–11 reports that upon entering the Promised Land, the Israelites kept the Passover on the plains of Jericho and ate unleavened cakes and parched corn, produce of the land, the next day. 2 Kings 23:21–23 reports that King Josiah commanded the Israelites to keep the Passover in Jerusalem as part of Josiah’s reforms, but also notes that the Israelites had not kept such a Passover from the days of the Biblical judges nor in all the days of the kings of Israel or the kings of Judah, calling into question the observance of even Kings David and Solomon. The more reverent 2 Chronicles 8:12–13, however, reports that Solomon offered sacrifices on the Festivals, including the Feast of Unleavened Bread. And 2 Chronicles 30:1–27 reports King Hezekiah’s observance of a second Passover anew, as sufficient numbers of neither the priests nor the people were prepared to do so before then. And Ezra 6:19–22 reports that the Israelites returned from the Babylonian captivity observed Passover, ate the Passover lamb, and kept the Feast of Unleavened Bread seven days with joy.

Numbers chapter 10

In Numbers 10:9, the Israelites were instructed to blow upon their trumpets to be “remembered before the Lord” and delivered from their enemies. Similarly, God remembered Noah to deliver him from the flood in Genesis 8:1; God promised to remember God’s covenant not to destroy the Earth again by flood in Genesis 9:15–16; God remembered Abraham to deliver Lot from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19:29; God remembered Rachel to deliver her from childlessness in Genesis 30:22; God remembered God’s covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to deliver the Israelites from Egyptian bondage in Exodus 2:24 and 6:5–6; Moses called on God to remember God’s covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to deliver the Israelites from God’s wrath after the incident of the Golden Calf in Exodus 32:13 and Deuteronomy 9:27; God promised to remember God’s covenant with Jacob, Isaac, and Abraham to deliver the Israelites and the Land of Israel in Leviticus 26:42–45; Samson called on God to deliver him from the Philistines in Judges 16:28; Hannah prayed for God to remember her and deliver her from childlessness in 1 Samuel 1:11 and God remembered Hannah’s prayer to deliver her from childlessness in 1 Samuel 1:19; Hezekiah called on God to remember Hezekiah’s faithfulness to deliver him from sickness in 2 Kings 20:3 and Isaiah 38:3; Jeremiah called on God to remember God’s covenant with the Israelites to not condemn them in Jeremiah 14:21; Jeremiah called on God to remember him and think of him, and avenge him of his persecutors in Jeremiah 15:15; God promised to remember God’s covenant with the Israelites and establish an everlasting covenant in Ezekiel 16:60; God remembers the cry of the humble in Zion to avenge them in Psalm 9:13; David called upon God to remember God’s compassion and mercy in Psalm 25:6; Asaph called on God to remember God’s congregation to deliver them from their enemies in Psalm 74:2; God remembered that the Israelites were only human in Psalm 78:39; Ethan the Ezrahite called on God to remember how short Ethan’s life was in Psalm 89:48; God remembers that humans are but dust in Psalm 103:14; God remembers God’s covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in Psalm 105:8–10; God remembers God’s word to Abraham to deliver the Israelites to the Land of Israel in Psalm 105:42–44; the Psalmist calls on God to remember him to favor God’s people, to think of him at God’s salvation, that he might behold the prosperity of God’s people in Psalm 106:4–5; God remembered God’s covenant and repented according to God’s mercy to deliver the Israelites in the wake of their rebellion and iniquity in Psalm 106:4–5; the Psalmist calls on God to remember God’s word to God’s servant to give him hope in Psalm 119:49; God remembered us in our low estate to deliver us from our adversaries in Psalm 136:23–24; Job called on God to remember him to deliver him from God’s wrath in Job 14:13; Nehemiah prayed to God to remember God’s promise to Moses to deliver the Israelites from exile in Nehemiah 1:8; and Nehemiah prayed to God to remember him to deliver him for good in Nehemiah 13:14–31.

Numbers chapter 12

God’s reference to Moses as “my servant” (Template:Hebrew, avdi) in Numbers 12:7 and 12:8 echoes God’s application of the same term to Abraham.[58] And later, God used the term to refer to Caleb,[59] Moses,[60] David,[61] Isaiah,[62] Eliakim the son of Hilkiah,[63] Israel,[64] Nebuchadnezzar,[65] Zerubbabel,[66] the Branch,[67] and Job.[68]

The Hebrew Bible reports skin disease (Template:Hebrew, tzara’at) and a person affected by skin disease (Template:Hebrew, metzora) at several places, often (and sometimes incorrectly) translated as “leprosy” and “a leper.” In Exodus 4:6, to help Moses to convince others that God had sent him, God instructed Moses to put his hand into his bosom, and when he took it out, his hand was “leprous (Template:Hebrew, m’tzora’at), as white as snow.” In Leviticus 13–14, the Torah sets out regulations for skin disease (Template:Hebrew, tzara’at) and a person affected by skin disease (Template:Hebrew, metzora). In Numbers 12:10, after Miriam spoke against Moses, God’s cloud removed from the Tent of Meeting and “Miriam was leprous (Template:Hebrew, m’tzora’at), as white as snow.” In Deuteronomy 24:8–9, Moses warned the Israelites in the case of skin disease (Template:Hebrew, tzara’at) diligently to observe all that the priests would teach them, remembering what God did to Miriam. In 2 Kings 5:1–19, part of the haftarah for parashah Tazria, the prophet Elisha cures Naaman, the commander of the army of the king of Aram, who was a “leper” (Template:Hebrew, metzora). In 2 Kings 7:3–20, part of the haftarah for parashah Metzora, the story is told of four “leprous men” (Template:Hebrew, m’tzora’im) at the gate during the Arameans’ siege of Samaria. And in 2 Chronicles 26:19, after King Uzziah tried to burn incense in the Temple in Jerusalem, “leprosy (Template:Hebrew, tzara’at) broke forth on his forehead.”

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:

Numbers chapter 8

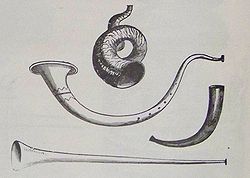

A Baraita interpreted the expression “beaten work of gold” in Numbers 8:4 to require that if the craftsmen made the menorah out of gold, then they had to beat it out of one single piece of gold. The Gemara then reasoned that Numbers 8:4 used the expression “beaten work” a second time to differentiate the requirements for crafting the menorah from the requirements for crafting the trumpets in Numbers 10:2, which used the expression “beaten work” only once. The Gemara concluded that the verse required the craftsmen to beat the menorah from a single piece of metal, but not so the trumpets.[69]

A Midrash deduced from Numbers 8:4 that the work of the candlestick was one of four things that God had to show Moses with God’s finger because Moses was puzzled by them.[70]

A Midrash explained why the consecration of the Levites in Numbers 8:5–26 followed soon after the presentation of the twelve tribes' offerings in Numbers 7:10–88 The Midrash noted that while the twelve tribes presented offerings at the dedication of the altar, the tribe of Levi did not offer anything. The Levites thus complained that they had been held back from bringing an offering for the dedication of the altar. The Midrash compared this to the case of a king who held a feast and invited various craftsmen, but did not invite a friend of whom the king was quite fond. The friend was distressed, thinking that perhaps the king harbored some grievance against him. But when the feast was over, the king called the friend and told him that while the king had made a feast for all the citizens of the province, the king would make a special feast with the friend alone, because of his friendship. So it was with God, who accepted the offerings of the twelve tribes in Numbers 7:5, and then turned to the tribe of Levi, addressing Aaron in Numbers 8:2 and directing the consecration of the Levites in Numbers 8:6–19.[71]

The Mishnah interpreted Numbers 8:7 to command the Levites to cut off all their hair with a razor, and not leave so much as two hairs remaining.[72]

Rabbi Jose the Galilean cited the use of “second” in Numbers 8:8 to rule that bulls brought for sacrifices had to be no more than two years old. But the Sages ruled that bulls could be as many as three years old, and Rabbi Meir ruled that even those that are four or five years old were valid, but old animals were not brought out of respect.[73]

A Midrash interpreted God’s words “the Levites shall be Mine” in Numbers 8:14 to indicate a relationship that will never cease, either in this world or in the World to Come.[74]

The Mishnah deduced from Numbers 8:16 that before Moses set up the Tabernacle, the firstborn performed sacrifices, but after Moses set up the Tabernacle, priests performed the sacrifices.[75]

Rabbi Judan considered God’s five mentions of “Israel” in Numbers 8:19 to demonstrate how much God loves Israel.[76]

A Midrash noted that Numbers 8:24 says, “from 25 years old and upward they shall go in to perform the service in the work of the tent of meeting,” while Numbers 4:3, 23, 30, 35, 39, 43, and 47 say that Levites “30 years old and upward” did service in the tent of meeting. The Midrash deduced that the difference teaches that all those five years, from the age of 25 to the age of 30, Levites served apprenticeships, and from that time onward they were allowed to draw near to do service. The Midrash concluded that a Levite could not enter the Temple courtyard to do service unless he had served an apprenticeship of five years. And the Midrash inferred from this that students who see no sign of success in their studies within a period of five years will never see any. Rabbi Jose said that students had to see success within three years, basing his position on the words “that they should be nourished three years” in Daniel 1:5.[77]

Numbers chapter 9

The Gemara noted that the events beginning in Numbers 9:1, set "in the first month of the second year," occurred before the events at the beginning of the book of Numbers, which Numbers 1:1 reports began in "the second month, in the second year." Rav Menasia bar Tahlifa said in Rav's name that this proved that there is no chronological order in the Torah.[78]

The Sifre concluded that Numbers 9:1–5 records the disgrace of the Israelites, as Numbers 9:1–5 reports the only Passover that the Israelites observed in the wilderness.[79]

Rav Nahman bar Isaac noted that both Numbers 1:1 and Numbers 9:1 begin, "And the Lord spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai," and deduced that just as Numbers 1:1 happened (in the words of that verse) "on the first day of the second month," so too Numbers 9:1 happened at the beginning of the month. And as Numbers 9:1 addressed the Passover offering, which the Israelites were to bring on the 14th of the month, the Gemara concluded that one should expound the laws of a holiday two weeks before the holiday.[80]

Chapter 9 of Tractate Pesachim in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud and chapter 8 of Tractate Pisha (Pesachim) in the Tosefta interpreted the laws of the second Passover in Numbers 9:1–14.[81] And Tractate Pesachim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of Passover generally in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8.[82]

Interpreting Numbers 9:9–10, the Mishnah taught that anyone who was “unclean by reason [of contact] with a dead body or on a distant journey” and did not observe the first Passover was obliged to observe the second Passover. Furthermore, the Mishnah taught that if anyone unintentionally erred or was prevented from observing and thus did not observe the first Passover, then that person was obliged to observe the second Passover. The Mishnah asked why then Numbers 9:10 specified that people “unclean by reason of [contact with] a dead body or on a distant journey” observed the second Passover. The Mishnah answered that it was to teach that those “unclean by reason of [contact with] a dead body or on a distant journey” were exempt from being cut off from their kin, while those who deliberately failed to observe the Passover were liable to being cut off from their kin.[83]

Interpreting Numbers 9:10, Rabbi Akiva taught that “a distant journey” was one from Modi’in and beyond, and the same distance in any direction from Jerusalem. But Rabbi Eliezer said that a journey was distant anytime one left the threshold of the Temple Court. And Rabbi Yose replied that it is for that reason that there is a dot over the letter hei (Template:Hebrew) in the word “distant” (Template:Hebrew, rechokah) in Numbers 9:10 in a Torah scroll, so as to teach that it was not really distant, but when one had departed from the threshold of the Temple Court, one was regarded as being on “a distant journey.”[84]

The Mishnah noted differences between the first Passover in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:15; 34:25; Leviticus 23:4–8; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–25; and Deuteronomy 16:1–8. and the second Passover in Numbers 9:9–13. The Mishnah taught that the prohibitions of Exodus 12:19 that “seven days shall there be no leaven found in your houses” and of Exodus 13:7 that “no leaven shall be seen in all your territory” applied to the first Passover; while at the second Passover, one could have both leavened and unleavened bread in one’s house. And the Mishnah taught that for the first Passover, one was required to recite the Hallel (Psalms 113–118) when the Passover lamb was eaten; while the second Passover did not require the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lamb was eaten. But both the first and second Passovers required the reciting of Hallel when the Passover lambs were offered, and both Passover lambs were eaten roasted with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. And both the first and second Passovers took precedence over the Sabbath.[85]

Tractate Beitzah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws common to all of the Festivals in Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49; 13:6–10; 23:16; 34:18–23; Leviticus 16; 23:4–43; Numbers 9:1–14; 28:16–30:1; and Deuteronomy 16:1–17; 31:10–13.[86]

Rabbi Jose the Galilean taught that the “certain men who were unclean by the dead body of a man, so that they could not keep the Passover on that day” in Numbers 9:6 were those who bore Joseph’s coffin, as implied in Genesis 50:25 and Exodus 13:19. The Gemara cited their doing so to support the law that one who is engaged on one religious duty is free from any other.[87] Rabbi Akiba said that they were Mishael and Elzaphan who were occupied with the remains of Nadab and Abihu (as reported in Leviticus 10:1–5). Rabbi Isaac argued, however, that if they were those who bore the coffin of Joseph or if they were Mishael and Elzaphan, they would have had time to cleanse themselves before Passover. Rather, Rabbi Isaac identified the men as some who were occupied with the obligation to bury an abandoned corpse (met mitzvah).[88]

The Mishnah counted the sin of failing to observe the Passover enumerated in Numbers 9:13 as one of 36 sins punishable by the penalty of being cut off from the Israelite people.[89]

Abaye deduced from the words "And on the day that the tabernacle was reared up" in Numbers 9:15 that the Israelites erected the Tabernacle only during the daytime, not at night, and thus that the building of the Temple could not take place at night.[90]

The Sifre asked how one could reconcile the report of Numbers 9:23 that “at the commandment of the Lord they journeyed” with the report of Numbers 10:35 that whenever they traveled, “Moses said: ‘Rise up, O Lord.’” The Sifre compared the matter to the case of a king who told his servant to arrange things so that the king could hand over an inheritance to his son. Alternatively, the Sifre compared the matter to the case of a king who went along with his ally. As the king was setting out, he said that he would not set out until his ally came.[91]

Numbers chapter 10

It was taught in a Baraita that Rabbi Josiah taught that the expression “make for yourself” (Template:Hebrew, aseih lecha) in Numbers 10:2 was a command for Moses to take from his own funds, in contrast to the expression “they shall take for you” (Template:Hebrew, v’yikhu eileicha) in Exodus 27:20, which was a command for Moses to take from communal funds.[92]

The Sifre deduced from the words “And the cloud of the Lord was over them by day” in Numbers 10:34 that God’s cloud hovered over the people with disabilities and illnesses — including those afflicted with emissions and skins diseases that removed them from the camp proper — protecting those with special needs.[93]

Our Rabbis taught that inverted nuns ( ] ) bracket the verses Numbers 10:35–36, about how the Ark would move, to teach that the verses are not in their proper place. But Rabbi said that the nuns do not appear there on that account, but because Numbers 10:35–36 constitute a separate book. It thus follows according to Rabbi that there are seven books of the Torah, and this accords with the interpretation that Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani made in the name of Rabbi Jonathan of Proverbs 9:1, when it says, “She [Wisdom] has hewn out her seven pillars,” referring to seven Books of the Law. Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel, however, taught that Numbers 10:35–36 were written where they are to provide a break between two accounts of Israel’s transgressions. The first account appears in Numbers 10:33, “they set forward from the mount of the Lord three days' journey,” which Rabbi Hama ben Hanina said meant that the Israelites turned away from following the Lord within three short days, and the second account appears in Numbers 11:1, which reports the Israelites’ murmurings. Rav Ashi taught that Numbers 10:35–36 more properly belong in Numbers 2, which reports how the Tabernacle would move.[94]

Numbers chapter 11

Rav and Samuel debated how to interpret the report of Numbers 11:5 that the Israelites complained: “We remember the fish, which we ate in Egypt for free.” One read “fish” literally, while the other read “fish” to mean the illicit intercourse that they were “free” to have when they were in Egypt, before the commandments of Sinai. Rabbi Ammi and Rabbi Assi disputed the meaning of the report of Numbers 11:5 that the Israelites remembered the cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions, and garlic of Egypt. One said that manna had the taste of every kind of food except these five; while the other said that manna had both the taste and the substance of all foods except these, for which manna had only the taste without the substance.[95]

The Gemara asked how one could reconcile Numbers 11:9, which reported that manna fell “upon the camp,” with Numbers 11:8, which reported that “people went about and gathered it,” implying that they had to leave the camp to get it. The Gemara concluded that the manna fell at different places for different classes of people: For the righteous, it fell in front of their homes; for average folk, it fell just outside the camp, and they went out and gathered; and for the wicked, it fell at some distance, and they had to go about to gather it.[96]

The Gemara asked how one could reconcile Exodus 16:4, which reported that manna fell as “bread from heaven”; with Numbers 11:8, which reported that people “made cakes of it,” implying that it required baking; with Numbers 11:8, which reported that people “ground it in mills,” implying that it required grinding. The Gemara concluded that the manna fell in different forms for different classes of people: For the righteous, it fell as bread; for average folk, it fell as cakes that required baking; and for the wicked, it fell as kernels that required grinding.[97]

Rav Judah said in the name of Rav (or others say Rabbi Hama ben Hanina) that the words “ground it in mortars” in Numbers 11:8 taught that with the manna came down women’s cosmetics, which were also ground in mortars. Rabbi Hama interpreted the words “seethed it in pots” in Numbers 11:8 to teach that with the manna came down the ingredients or seasonings for a cooked dish. Rabbi Abbahu interpreted the words “the taste of it was as the taste of a cake (leshad) baked with oil” in Numbers 11:8 to teach that just as infants find many flavors in the milk of their mother’s breast (shad), so the Israelites found many tastes in the manna.[98] The Gemara asked how one could reconcile Numbers 11:8, which reported that “the taste of it was as the taste of a cake baked with oil,” with Exodus 16:31, which reported that “the taste of it was like wafers made with honey.” Rabbi Jose ben Hanina said that the manna tasted differently for different classes of people: It tasted like honey for infants, bread for youths, and oil for the aged.[99]

Rabbi Eleazar, on the authority of Rabbi Simlai, noted that Deuteronomy 1:16 says, “And I charged your judges at that time,” while Deuteronomy 1:18 similarly says, “I charged you [the Israelites] at that time.” Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Deuteronomy 1:18 meant to warn the Congregation to revere their judges, and Deuteronomy 1:16 meant to warn the judges to be patient with the Congregation. Rabbi Hanan (or some say Rabbi Shabatai) said that this meant that judges must be as patient as Moses, who Numbers 11:12 reports acted “as the nursing father carries the sucking child.”[100]

A Midrash asked why in Numbers 11:16, God directed Moses to gather 70 elders of Israel, when Exodus 29:9 reported that there already were 70 elders of Israel. The Midrash deduced that when in Numbers 11:1, the people murmured, speaking evil, and God sent fire to devour part of the camp, all those earlier 70 elders had been burned up. The Midrash continued that the earlier 70 elders were consumed like Nadab and Abihu, because they too acted frivolously when (as reported in Exodus 24:11) they beheld God and inappropriately ate and drank. The Midrash taught that Nadab, Abihu, and the 70 elders deserved to die then, but because God so loved giving the Torah, God did not wish to disturb that time.[101]

Rabbi Hama ben Hanina taught that our ancestors were never without a scholars’ council. Abraham was an elder and a member of the scholars’ council, as Genesis 24:1 says, “And Abraham was an elder (Template:Hebrew, zaken) well stricken in age.” Eliezer, Abraham’s servant, was an elder and a member of the scholars’ council, as Genesis 24:2 says, “And Abraham said to his servant, the elder of his house, who ruled over all he had,” which Rabbi Eleazar explained to mean that he ruled over — and thus knew and had control of — the Torah of his master. Isaac was an elder and a member of the scholars’ council, as Genesis 27:1 says: “And it came to pass when Isaac was an elder (Template:Hebrew, zaken).” Jacob was an elder and a member of the scholars’ council, as Genesis 48:10 says, “Now the eyes of Israel were dim with age (Template:Hebrew, zoken).” In Egypt they had the scholars’ council, as Exodus 3:16 says, “Go and gather the elders of Israel together.” And in the Wilderness, they had the scholars’ council, as in Numbers 11:16, God directed Moses to “Gather . . . 70 men of the elders of Israel.”[102]

The Mishnah deduced from Numbers 11:16 that the Great Sanhedrin consisted of 71 members, because God instructed Moses to gather 70 elders of Israel, and Moses at their head made 71. Rabbi Judah said that it consisted only of 70.[103]

Rav Aha bar Jacob argued for an interpretation of the words “that they may stand there with you” with regard to the 70 judges in Numbers 11:16. Rav Aha bar Jacob argued that the words “with you” implied that the judges needed to be “like you” — that is, like Moses — in unblemished genealogical background. But the Gemara did not accept that argument.[104]

The Gemara asked how one could reconcile Numbers 11:20, which reported God’s promise that the Israelites would eat meat “a whole month,” with Numbers 11:33, which reported that “while the flesh was still between their teeth, before it was chewed, . . . the Lord smote the people.” The Gemara concluded that God’s punishment came at different speeds for different classes of people: Average people died immediately; while the wicked suffered over a month before they died.[105]

Reading God’s criticism of Moses in Numbers 20:12, “Because you did not believe in me,” a Midrash asked whether Moses had not previously said worse when in Numbers 11:22, he showed a greater lack of faith and questioned God’s powers asking: “If flocks and herds be slain for them, will they suffice them? Or if all the fish of the sea be gathered together for them, will they suffice them?” The Midrash explained by relating the case of a king who had a friend who displayed arrogance towards the king privately, using harsh words. The king did not, however, lose his temper with his friend. Later, the friend displayed his arrogance in the presence of the king’s legions, and the king sentenced his friend to death. So also God told Moses that the first offense that Moses committed (in Numbers 11:22) was a private matter between Moses and God. But now that Moses had committed a second offense against God in public, it was impossible for God to overlook it, and God had to react, as Numbers 20:12 reports, “To sanctify Me in the eyes of the children of Israel.”[106]

The Gemara explained how Moses selected the members of the Sanhedrin in Numbers 11:24. The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that when (in Numbers 11:16) God told Moses to gather 70 elders of Israel, Moses worried that if he chose six from each of the 12 tribes, there would be 72 elders, two more than God requested. If he chose five elders from each tribe, there would be 60 elders, ten short of the number God requested. If Moses chose six out of some tribes and five out of others, he would sow jealousy among the tribes. To solve this problem, Moses selected six prospective elders out of each tribe. Then he brought 72 lots, on 70 of which he wrote the word “elder” and two of which he left blank. He then mixed up all the lots, put them in an urn, and asked the 72 prospective elders to draw lots. To each prospective elder who drew a lot marked “elder,” Moses said that Heaven had consecrated him. To those two prospective elders who drew a blank, Moses said that Heaven had rejected them, what could Moses do? According to this Baraita, some say the report in Numbers 11:26 that Eldad and Medad remained in the camp meant that their lots — marked “elder” — remained in the urn, as Eldad and Medad were afraid to draw their lots. Other prospective elders drew the two blank lots, so Eldad and Medad were thus selected elders.[107]

Rabbi Simeon expounded a different view on the report in Numbers 11:26 that Eldad and Medad remained in the camp. When God ordered Moses in Numbers 11:16 to gather 70 of the elders of Israel, Eldad and Medad protested that they were not worthy of that dignity. In reward for their humility, God added yet more greatness to their greatness; so while the other elders’ prophesying ceased, Eldad’s and Medad’s prophesying continued. Rabbi Simeon taught that Eldad and Medad prophesied that Moses would die and Joshua would bring Israel into the Land of Israel. Abba Hanin taught in the name of Rabbi Eliezer that Eldad and Medad prophesied concerning the matter of the quails in Numbers 11, calling on the quail to arise. Rav Nahman read Ezekiel 38:17 to teach that they prophesied concerning Gog and Magog. The Gemara found support for Rabbi Simeon’s assertion that while the other elders’ prophesying ceased, Eldad’s and Medad’s prophesying continued in the use by Numbers 11:25 of the past tense, “and they prophesied,” to describe the other elders, whereas Numbers 11:27 uses the present tense with regard to Eldad and Medad. The Gemara taught that if Eldad and Medad prophesied that Moses would die, then that explains why Joshua in Numbers 11:28 requested Moses to forbid them. The Gemara reasoned that if Eldad and Medad prophesied about the quail or Gog and Magog, then Joshua asked Moses to forbid them because their behavior did not appear seemly, like a student who issues legal rulings in the presence of his teacher. The Gemara further reasoned that according to those who said that Eldad and Medad prophesied about the quail or Gog and Magog, Moses’ response in Numbers 11:28, “Would that all the Lord's people were prophets,” made sense. But if Eldad and Medad prophesied that Moses would die, the Gemara wondered why Moses expressed pleasure with that in Numbers 11:28. The Gemara explained that Moses must not have heard their entire prophecy. And the Gemara interpreted Joshua’s request in Numbers 11:28 for Moses to “forbid them” to mean that Moses should give Eldad and Medad public burdens that would cause them to cease their prophesying.[108]

Numbers chapter 12

The Gemara cited Numbers 12:3 for the proposition that prophets had to be meek. In Deuteronomy 18:15, Moses foretold that “A prophet will the Lord your God raise up for you . . . like me,” and Rabbi Johanan thus taught that prophets would have to be, like Moses, strong, wealthy, wise, and meek. Strong, for Exodus 40:19 says of Moses, “he spread the tent over the tabernacle,” and a Master taught that Moses himself spread it, and Exodus 26:16 reports, “Ten cubits shall be the length of a board.” Similarly, the strength of Moses can be derived from Deuteronomy 9:17, in which Moses reports, “And I took the two tablets, and cast them out of my two hands, and broke them,” and it was taught that the tablets were six handbreadths in length, six in breadth, and three in thickness. Wealthy, as Exodus 34:1 reports God’s instruction to Moses, “Carve yourself two tablets of stone,” and the Rabbis interpreted the verse to teach that the chips would belong to Moses. Wise, for Rav and Samuel both said that 50 gates of understanding were created in the world, and all but one were given to Moses, for Psalm 8:6 said of Moses, “You have made him a little lower than God.” Meek, for Numbers 12:3 reports, “Now the man Moses was very meek.”[109]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that Moses beheld the likeness of God in Numbers 12:8 in compensation for a pious thing that Moses did. A Baraita taught in the name of Rabbi Joshua ben Korhah that God told Moses that when God wanted to be seen at the burning bush, Moses did not want to see God’s face; Moses hid his face in Exodus 3:6, for he was afraid to look upon God. And then in Exodus 33:18, when Moses wanted to see God, God did not want to be seen; in Exodus 33:20, God said, “You cannot see My face.” But Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that in compensation for three pious acts that Moses did at the burning bush, he was privileged to obtain three rewards. In reward for hiding his face in Exodus 3:6, his face shone in Exodus 34:29. In reward for his fear of God in Exodus 3:6, the Israelites were afraid to come near him in Exodus 34:30. In reward for his reticence “to look upon God,” he beheld the likeness of God in Numbers 12:8.[110]

The Gemara reported that some taught that in Numbers 12:8, God approved of the decision of Moses to abstain from marital relations so as to remain pure for his communication with God. A Baraita taught that Moses did three things of his own understanding, and God approved: (1) He added one day of abstinence of his own understanding; (2) he separated himself from his wife (entirely, after the Revelation); and (3) he broke the Tables (on which God had written the Ten Commandments). The Gemara explained that to reach his decision to separate himself from his wife, Moses applied an a fortiori (kal va-chomer) argument to himself. Moses noted that even though the Shechinah spoke with the Israelites on only one definite, appointed time (at Mount Sinai), God nonetheless instructed in Exodus 19:10, "Be ready against the third day: come not near a woman." Moses reasoned that if he heard from the Shechinah at all times and not only at one appointed time, how much more so should he abstain from marital contact. And the Gemara taught that we know that God approved, because in Deuteronomy 5:27, God instructed Moses (after the Revelation at Sinai), "Go say to them, 'Return to your tents'" (thus giving the Israelites permission to resume marital relations) and immediately thereafter in Deuteronomy 5:28, God told Moses, "But as for you, stand here by me" (excluding him from the permission to return). And the Gemara taught that some cite as proof of God's approval God's statement in Numbers 12:8, "with him [Moses] will I speak mouth to mouth" (as God thus distinguished the level of communication God had with Moses, after Miriam and Aaron had raised the marriage of Moses and then questioned the distinctiveness of the prophecy of Moses).[111]

It was taught in a Baraita that four types of people are accounted as though they were dead: a poor person, a person affected by skin disease (Template:Hebrew, metzora), a blind person, and one who is childless. A poor person is accounted as dead, for Exodus 4:19 says, “for all the men are dead who sought your life” (and the Gemara interpreted this to mean that they had been stricken with poverty). A person affected by skin disease (Template:Hebrew, metzora) is accounted as dead, for Numbers 12:10–12 says, “And Aaron looked upon Miriam, and behold, she was leprous (Template:Hebrew, metzora’at). And Aaron said to Moses . . . let her not be as one dead.” The blind are accounted as dead, for Lamentations 3:6 says, “He has set me in dark places, as they that be dead of old.” And one who is childless is accounted as dead, for in Genesis 30:1, Rachel said, “Give me children, or else I am dead.”[112]

Rabbi Ishmael cited Numbers 12:14 as one of ten a fortiori (kal va-chomer) recorded in the Hebrew Bible: (1) In Genesis 44:8, Joseph’s brothers told Joseph, “Behold, the money that we found in our sacks’ mouths we brought back to you,” and they thus reasoned, “how then should we steal?” (2) In Exodus 6:12, Moses told God, “Behold, the children of Israel have not hearkened to me,” and reasoned that surely all the more, “How then shall Pharaoh hear me?” (3) In Deuteronomy 31:27, Moses said to the Israelites, “Behold, while I am yet alive with you this day, you have been rebellious against the Lord,” and reasoned that it would follow, “And how much more after my death?” (4) In Numbers 12:14, “the Lord said to Moses: ‘If her (Miriam’s) father had but spit in her face,’” surely it would stand to reason, “‘Should she not hide in shame seven days?’” (5) In Jeremiah 12:5, the prophet asked, “If you have run with the footmen, and they have wearied you,” is it not logical to conclude, “Then how can you contend with horses?” (6) In 1 Samuel 23:3, David's men said to him, “Behold, we are afraid here in Judah,” and thus surely it stands to reason, “How much more then if we go to Keilah?” (7) Also in Jeremiah 12:5, the prophet asked, “And if in a land of Peace where you are secure” you are overcome, is it not logical to ask, “How will you do in the thickets of the Jordan?” (8) Proverbs 11:31 reasoned, “Behold, the righteous shall be requited in the earth,” and does it not follow, “How much more the wicked and the sinner?” (9) In Esther 9:12, “The king said to Esther the queen: ‘The Jews have slain and destroyed 500 men in Shushan the castle,’” and it thus stands to reason, “‘What then have they done in the rest of the king’s provinces?’” (10) In Ezekiel 15:5, God came to the prophet saying, “Behold, when it was whole, it was usable for no work,” and thus surely it is logical to argue, “How much less, when the fire has devoured it, and it is singed?”[113]

The Mishnah cited Numbers 12:15 for the proposition that Providence treats a person measure for measure as that person treats others. And so because, as Exodus 2:4 relates, Miriam waited for the baby Moses in the Nile, so the Israelites waited seven days for Miriam in the wilderness in Numbers 12:15.[114]

Commandments

According to both Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 3 positive and 2 negative commandments in the parashah:[115]

- To slaughter the second Passover lamb[116]

- To eat the second Passover lamb in accordance with the Passover rituals[117]

- Not to leave the second Passover meat over until morning[118]

- Not to break any bones from the second Passover offering[119]

- To sound alarm in times of catastrophe[120]

In the liturgy

Some Jews read “at 50 years old one offers counsel,” reflecting the retirement age for Levites in Numbers 8:25, as they study Pirkei Avot chapter 6 on a Sabbath between Passover and Rosh Hashanah.[121]

The laws of the Passover offering in Numbers 9:2 provide an application of the second of the Thirteen Rules for interpreting the Torah in the Baraita of Rabbi Ishmael that many Jews read as part of the readings before the Pesukei d’Zimrah prayer service. The second rule provides that similar words in different contexts invite the reader to find a connection between the two topics. The words “in its proper time” (Template:Hebrew, bemoado) in Numbers 28:2 indicate that the priests needed to bring the daily offering “in its proper time,” even on a Sabbath. Applying the second rule, the same words in Numbers 9:2 mean that the priests needed to bring the Passover offering “in its proper time,” even on a Sabbath.[122]

The Passover Haggadah, in the korech section of the Seder, quotes the words “they shall eat it with unleavened bread and bitter herbs” from Numbers 9:11 to support Hillel’s practice of combining matzah and maror together in a sandwich.[123]

Jews sing the words “at the commandment of the Lord by the hand of Moses” (Template:Hebrew, al pi Adonai b’yad Moshe) from Numbers 9:23 while looking at the raised Torah during the lifting of the Torah (Hagbahah) after the Torah reading.[124]

Based on the command of Numbers 10:10 to remember the Festivals, on the new month (Rosh Chodesh) and intermediate days (Chol HaMoed) of Passover and Sukkot, Jews add a paragraph to the weekday afternoon (Minchah) Amidah prayer just before the prayer of thanksgiving (Modim).[125]

Jews chant the description of how the Israelites carried the Ark of the Covenant in Numbers 10:35 (Template:Hebrew, kumah Adonai, v’yafutzu oyvecha, v’yanusu m’sanecha, mipanecha) during the Torah service when the Ark containing the Torah is opened. And Jews chant the description of how the Israelites set the Ark of the Covenant down in Numbers 10:36 (Template:Hebrew, uv’nuchoh yomar: shuvah Adonai, riv’vot alfei Yisrael) during the Torah service when the Torah is returned to the Ark.[126]

The characterization of Moses as God’s “trusted servant” in Numbers 12:7 finds reflection shortly after the beginning of the Kedushah section in the Sabbath morning (Shacharit) Amidah prayer.[127]

In the Yigdal hymn, the eighth verse, “God gave His people a Torah of truth, by means of His prophet, the most trusted of His household,” reflects Numbers 12:7–8.[128]

The 16th Century Safed Rabbi Eliezer Azikri quoted the words of the prayer of Moses “Please God” (Template:Hebrew, El nah) in Numbers 12:13 in his kabbalistic poem Yedid Nefesh (“Soul’s Beloved”), which in turn many congregations chant just before the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service.[129]

The prayer of Moses for Miriam’s health in Numbers 12:13, “Heal her now, O God, I beseech You” (Template:Hebrew, El, nah r’fah nah lah) — just five simple words in Hebrew — demonstrates that it is not the length of a prayer that matters.[130]

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is Zechariah 2:14–4:7.

Connection to the parashah

Both the parashah and the haftarah discuss the lampstand (Template:Hebrew, menorah).[131] Text of Zechariah shortly after that of the haftarah explains that the lights of the lampstand symbolize God’s eyes, keeping watch on the earth.[132] And in the haftarah, God’s angel explains the message of Zechariah’s vision of the lampstand: “Not by might, nor by power, but by My spirit, says the Lord of hosts.”[133] Both the parashah and the haftarah also discuss the purification of priests and their clothes, the parashah in the purification of the Levites[134] and the haftarah in the purification of the High Priest Joshua.[135]

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Exodus 12:3–27, 43–49 (Passover); 13:6–10 (Passover); 25:31–37 (lampstand); 34:25 (Passover); 40:24–25 (lampstand).

- Leviticus 23:4–8 (Passover); 24:10–16 (inquiry of God on the law).

- Numbers 15:32–36 (inquiry of God on the law); 27:1–11 (inquiry of God on the law); 28:16–25 (Passover).

- Deuteronomy 9:22 (Kibroth-hattaavah); 16:1–8 (Passover).

- Psalms 22:23 (congregation); 25:14 (hearing God’s counsel); 26:6 (cleansing); 35:18 (congregation); 40:10–11 (congregation); 48:15 (God as guide); 68:2–3 (let God arise, enemies be scattered); 73:24 (God as guide); 76:9 (God’s voice); 78:14, 26, 30 (cloud; wind from God; food still in their mouths); 80:2 (God as guide; enthroned on cherubim); 81:4 (blowing the horn); 85:9 (hearing what God says); 88:4–7 (like one dead); 94:9 (God hears); 105:26 (Moses, God’s servant); 106:4, 42 (remember for salvation; enemies who oppressed); 107:7 (God as guide); 122:1 (going to God’s house); 132:8 (arise, God).

Early nonrabbinic

- The War Scroll. Dead Sea scroll 1QM 10:1–8a. Land of Israel, 1st Century BCE. Reprinted in, e.g., Géza Vermes. The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, 161, 173. New York: Penguin Press, 1997. ISBN 0-7139-9131-3.

- Philo. Allegorical Interpretation 1: 24:76; 2: 17:66; 3: 33:103, 59:169, 72:204; On the Birth of Abel and the Sacrifices Offered by Him and by His Brother Cain 18:66; 22:77; 26:86; That the Worse Is Wont To Attack the Better 19:63; On the Giants 6:24; On Drunkenness 10:39; On the Prayers and Curses Uttered by Noah When He Became Sober 4:19; On the Migration of Abraham 28:155; Who Is the Heir of Divine Things? 5:20; 15:80; 52:262; On the Change of Names 39:232; On Dreams, That They Are God-Sent 2:7:49; On the Life of Moses 2:42:230; The Special Laws 4:24:128–30; Questions and Answers on Genesis 1:91. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st Century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, 33, 45, 62, 69, 73, 102, 104–05, 119, 153, 210, 229, 268, 277, 282, 299, 361, 391, 511, 629, 810. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:12:5– 13:1. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 98–99. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- John 19:36 (“Not one of his bones will be broken”) 90–100 CE.

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Pesachim 1:1–10:9; Beitzah 1:1–5:7; Sotah 1:7–9; Sanhedrin 1:6; Zevachim 14:4; Keritot 1:1; Negaim 14:4; Parah 1:2. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 246, 449, 584, 731, 836, 1010, 1013. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Bikkurim 1:2; Pisha (Pesachim) 4:14; 8:1, 3; Shekalim 3:26; Sotah 4:2–4; 6:7–8; 7:18; Keritot 1:1; Parah 1:1–3; Yadayim 2:10. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 1:345, 493, 508–09, 538, 845, 857–58, 865; 2:1551, 1745–46, 1907. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Pub., 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifre to Numbers 59:1–106:3. Land of Israel, circa 250–350 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifré to Numbers: An American Translation and Explanation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 2:1–132. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986. ISBN 1-55540-010-8.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Berakhot 45a; Bikkurim 4b, 11b; Pesachim 1a–86a; Yoma 7a, 41b; Sukkah 31a; Beitzah 1a–49b; Rosh Hashanah 1b, 2b, 20b, 22a; Megillah 14a, 17b, 29a; Moed Katan 11b, 17a; Sanhedrin 10a–b, 22b. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 1, 12, 18–19, 21–24, 26, 28. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2005–2013.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon 5:2; 12:3; 16:2; 20:5; 22:2–23:1; 29:1; 37:1–2; 40:1–2; 43:1; 44:2; 47:2. Land of Israel, 5th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Translated by W. David Nelson, 14, 41, 55, 85, 98, 100, 102, 131, 159, 162, 170–72, 182, 186, 209. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2006. ISBN 0-8276-0799-7.

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 7a, 32a, 34a, 54b, 55b, 63b; Shabbat 31b, 87a, 115b–16a, 130a; Eruvin 2a, 40a; Pesachim 6b, 28b, 36a, 59a, 64a, 66a–67a, 69a–b, 77a, 79a, 80a, 85a, 90a–b, 91b, 92b–96b, 115a, 120a; Yoma 3b, 7a, 28b, 51a, 66a, 75a–76a; Sukkah 25a–b, 47b, 53a–54a, 55a; Rosh Hashanah 3a, 5a, 18a, 26b–27a, 32a, 34a; Taanit 7a, 29a, 30b; Megillah 5a, 21b, 31a; Moed Katan 5a, 15b, 16a–b; Chagigah 5b, 18b, 25b; Yevamot 63b, 103b; Ketubot 57b; Nedarim 38a, 64b; Nazir 5a, 15b, 40a, 63a; Sotah 9b, 33b; Gittin 60a–b; Kiddushin 32b, 37b, 76b; Bava Kamma 25a, 83a; Bava Metzia 86b; Bava Batra 91a, 111a, 121b; Sanhedrin 2a, 3b, 8a, 17a, 36b, 47a, 110a; Makkot 10a, 13b, 14b, 17a, 21a; Shevuot 15b, 16b; Avodah Zarah 5a, 24b; Horayot 4b, 5b; Zevachim 9b, 10b, 22b, 55a, 69b, 79a, 89b, 101b, 106b; Menachot 28a–b, 29a, 65b, 83b, 95a, 98b; Chullin 7b, 17a, 24a, 27b, 29a, 30a, 105a, 129b; Bekhorot 4b, 33a; Arakhin 10a, 11a–b, 15b; Keritot 2a, 7b. Babylonia, 6th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 vols. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval

- Saadia Gaon. The Book of Beliefs and Opinions, 2:10–11; 3:8–9; 5:3, 7; 9:8. Baghdad, Babylonia, 933. Translated by Samuel Rosenblatt, 116, 119, 127, 165, 170, 214, 230, 349. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1948. ISBN 0-300-04490-9.

- Rashi. Commentary. Numbers 8–12. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, 4:87–145. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-029-3.

- Solomon ibn Gabirol. A Crown for the King, 33:421. Spain, 11th Century. Translated by David R. Slavitt, 56–57. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-511962-2. (“mixed multitude” (asafsuf)).

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 2:26; 4:3, 11; 5:27. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. Reprinted in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Introduction by Henry Slonimsky, pages 102, 200–01, 212, 217, 295. New York: Schocken, 1964. ISBN 0-8052-0075-4.

- Numbers Rabbah 15:1–25. 12th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, 1:3–4, 10, 24, 30, 40, 45, 47, 54; 2:24, 30, 36, 41, 45; 3:2, 32, 36, 50. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, 3, 17–18, 23, 34, 39, 55, 58, 63, 75, 198, 214, 225, 234–35, 242, 245, 254, 324, 331, 383. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Zohar 1:6b, 76a, 148a, 171a, 176b, 183a, 243a, 249b; 2:21a, 54a, 62b, 82b, 86b, 130a, 196b, 203b, 205b, 224b, 241a; 3:118b, 127a–b, 146b, 148b–56b, 198b; Raya Mehemna 42b. Spain, late 13th Century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 vols. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

Modern

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:34, 36, 40, 42. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, 432, 460, 462, 464, 505, 595. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0-14-043195-0.

- Hirschel Levin. “Sermon on Be-Ha‘aloteka.” London, 1757 or 1758. In Marc Saperstein. Jewish Preaching, 1200–1800: An Anthology, 347–58. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-300-04355-4.

- Louis Ginzberg. Legends of the Jews, 3:455–97. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1911.

- Joel Roth. “On the Ordination of Women as Rabbis.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1984. HM 7.4.1984b. Reprinted in Responsa: 1980–1990: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by David J. Fine, 736, 741–42, 764, 773 n.38, 786 n.133. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2005. ISBN 0-916219-27-5. (women’s observance of commandments and role as witnesses).

- Phyllis Trible. “Bringing Miriam Out of the Shadows.” Bible Review. 5 (1) (Feb. 1989).

- Elliot N. Dorff. “A Jewish Approach to End-Stage Medical Care.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1990. YD 339:1.1990b. Reprinted in Responsa: 1980–1990: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by David J. Fine, 519, 535, 567 n.23. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2005. ISBN 0-916219-27-5. (the prayer of Moses in Numbers 11:15 and the endurance of pain).

- Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, 59–99, 367–87. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. ISBN 0-8276-0329-0.

- Baruch A. Levine. Numbers 1–20, 4:267–343. New York: Anchor Bible, 1993. ISBN 0-385-15651-0.

- Mary Douglas. In the Wilderness: The Doctrine of Defilement in the Book of Numbers, 58–59, 80, 84, 86, 103, 107, 109–12, 120–21, 123–26, 135–38, 141, 143, 145, 147, 167, 175, 186, 188–90, 192, 195–98, 200–01, 209–10. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Reprinted 2004. ISBN 0-19-924541-X.

- Bernhard W. Anderson. “Miriam’s Challenge: Why was Miriam severely punished for challenging Moses’ authority while Aaron got off scot-free? There is no way to avoid the fact that the story presupposes a patriarchal society.” Bible Review. 10 (3) (June 1994).

- Elliot N. Dorff. “Family Violence.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1995. HM 424.1995. Reprinted in Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, 773, 806. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. ISBN 0-916219-19-4. (laws of slander).

- Phyllis Trible. “Eve and Miriam: From the Margins to the Center.” In Feminist Approaches to the Bible: Symposium at the Smithsonian Institution September 24, 1994. Biblical Archaeology Society, 1995. ISBN 1-880317-41-9.

- Hershel Shanks. “Insight: Does the Bible refer to God as feminine?” Bible Review. 14 (2) (Apr. 1998).

- Elie Wiesel. “Supporting Roles: Eldad and Medad.” Bible Review. 15 (2) (Apr. 1999).

- Robert R. Stieglitz. “The Lowdown on the Riffraff: Do these obscure figures preserve a memory of a historical Exodus?” Bible Review. 15 (4) (Aug. 1999).

- J. Daniel Hays. “Moses: The private man behind the public leader.” Bible Review. 16 (4) (Aug. 2000):16–26, 60–63.

- Elie Kaplan Spitz. “Mamzerut.” New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2000. EH 4.2000a. Reprinted in Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, 558, 578. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. ISBN 0-916219-19-4. (Miriam’s speaking ill and leprosy).

- Marek Halter. Zipporah, Wife of Moses. New York: Crown, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-5279-3.

- Suzanne A. Brody. “Mocking Birds.” In Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems, 95. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. ISBN 1-60047-112-9.

- Simeon Chavel. “The Second Passover, Pilgrimage, and the Centralized Cult.” Harvard Theological Review. 102 (1) (Jan. 2009): 1–24.

- Alicia Jo Rabins. “Snow/Scorpions and Spiders.” In Girls in Trouble. New York: JDub Music, 2009. (song about Miriam’s being shut out of the camp for seven days).

External links

Texts

Commentaries

Notes

- ^ "Torah Stats — Bemidbar". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers. Edited by Menachem Davis, 60–87. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007. ISBN 1-4226-0208-7.

- ^ Numbers 8:1–3.

- ^ Numbers 8:5–7.

- ^ Numbers 8:9–10.

- ^ Numbers 8:11.

- ^ Numbers 8:12.

- ^ Numbers 8:15–16.

- ^ Numbers 8:23–26.

- ^ Numbers 9:1–3.

- ^ Numbers 9:6.

- ^ Numbers 9:7–8.

- ^ Numbers 9:9–12.

- ^ Numbers 9:13.

- ^ Numbers 9:15–16.

- ^ Numbers 9:17–23.

- ^ Numbers 10:1–2.

- ^ Numbers 10:3.

- ^ Numbers 10:4.

- ^ Numbers 10:5–6.

- ^ Numbers 10:9–10.

- ^ Numbers 10:11–12.

- ^ Numbers 10:29–30.

- ^ Numbers 10:31–32.

- ^ Numbers 10:33–34.

- ^ Numbers 10:35.

- ^ Numbers 10:36.

- ^ Numbers 11:1–2.

- ^ Numbers 11:4.

- ^ Numbers 11:11.

- ^ Numbers 11:16–17.

- ^ Numbers 11:18.

- ^ Numbers 11:21–22.

- ^ Numbers 11:23.

- ^ Numbers 11:24–25.

- ^ Numbers 11:25.

- ^ Numbers 11:26.

- ^ Numbers 11:27–28.

- ^ Numbers 11:29.

- ^ Numbers 11:31–32.

- ^ Numbers 11:33.

- ^ Numbers 12:1–2.

- ^ Numbers 12:2–4.

- ^ Numbers 12:5–8.

- ^ Numbers 12:10.

- ^ Numbers 12:13.

- ^ Numbers 12:14.

- ^ Numbers 12:15.

- ^ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. “Inner-biblical Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1829–35. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-529751-2.

- ^ Exodus 12:11, 21, 27, 43, 48; 34:25; Leviticus 23:5; Numbers 9:2, 4–6, 10, 12–14; 28:16; 33:3; Deuteronomy 16:1–2, 5–6; Joshua 5:10–11; 2 Kings 23:21–23; Ezekiel 45:21; Ezra 6:19–20; 2 Chronicles 30:1–2, 5, 15, 17–18; 35:1, 6–9, 11, 13, 16–19.

- ^ Exodus 12:17; 23:15; 34:18; Leviticus 23:6; Deuteronomy 16:16; Ezekiel 45:21; Ezra 6:22; 2 Chronicles 8:13; 30:13, 21; 35:17.

- ^ Exodus 12:16; Leviticus 23:7–8; Numbers 28:18, 25.

- ^ See, e.g., W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary, 456. New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981. ISBN 0-8074-0055-6.

- ^ Plaut, at 464.

- ^ Exodus 12:11, 21, 27, 43, 48; Deuteronomy 16:2, 5–6; Ezra 6:20; 2 Chronicles 30:15, 17–18; 35:1, 6–9, 11, 13.

- ^ Plaut, at 464.

- ^ Exodus 12:42; 23:15; 34:18; Numbers 33:3; Deuteronomy 16:1, 3, 6.

- ^ See Genesis 26:24.

- ^ See Numbers 14:24.

- ^ See Joshua 1:2 and 1:7; 2 Kings 21:8; and Malachi 3:22.

- ^ See 2 Samuel 3:18; 7:5; and 7:8; 1 Kings 11:13; 11:32; 11:34; 11:36; 11:38; and 14:8; 2 Kings 19:34 and 20:6; Isaiah 37:35; Jeremiah 33:21; 33:22; and 33:26; Ezekiel 34:23; 34:24; and 37:24; Psalm 89:3 and 89:20; and 1 Chronicles 17:4 and 17:7.

- ^ See Isaiah 20:3.

- ^ See Isaiah 22:20.

- ^ See Isaiah 41:8; 41:9; 42:1; 42:19; 43:10; 44:1; 44:2; 44:21; 49:3; 49:6; and 52:13; and Jeremiah 30:10; 46:27; and 46:27; and Ezekiel 28:25 and 37:25.

- ^ See Jeremiah 25:9; 27:6; and 43:10.

- ^ See Haggai 2:23.

- ^ See Zechariah 3:8.

- ^ See Job 1:8; 2:3; 42:7; and 42:8.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Menachot 28a.

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 15:28.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 15:3.

- ^ Mishnah Negaim 14:4.

- ^ Mishnah Parah 1:2.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 2:2.

- ^ Mishnah Zevachim 14:4. Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 112b.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 2:4.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 6:3. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5. See also Tosefta Shekalim 3:26.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 6b.

- ^ Sifre to Numbers 67:1.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 6b.

- ^ Mishnah Pesachim 9:1–4. Tosefta Pisha (Pesachim) 8:1–10. Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 92b–96b.

- ^ Mishnah Pesachim 1:1–10:9. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 229–51. Tosefta Pisha (Pesachim) 1:1–10:13. Jerusalem Talmud Pesachim 1a–86a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 18–19. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2011. Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 2a–121b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volumes 9–11. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997–1998.

- ^ Mishnah Passover 9:1. Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 92b.

- ^ Mishnah Pesachim 9:2. Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 93b.

- ^ Mishnah Pesachim 9:3. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 247. Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 95a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Dovid Kamenetsky, Eli Shulman, Feivel Wahl, and Mendy Wachsman; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 11, page 95a1.

- ^ Mishnah Beitzah 1:1–5:7. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 291–99. Tosefta Yom Tov (Beitzah) 1:1–4:11. Jerusalem Talmud Beitzah 1a–49b. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volume 23. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2010. ISBN 1-4226-0246-X. Babylonian Talmud Beitzah 2a–40b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Yisroel Reisman; edited by Hersh Goldwurm, volume 17. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1991. ISBN 1-57819-616-7.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 25a. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Asher Dicker and Avrohom Neuberger; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 15, page 25a4. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1998. ISBN 1-57819-610-8.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 25b.

- ^ Mishnah Keritot 1:1. Babylonian Talmud Keritot 2a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Shevuot 15b.

- ^ Sifre to Numbers 84:2.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 3b.

- ^ Sifre to Numbers 83:2.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 115b–16a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 75a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 75a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 75a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 75a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 75b.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 8a.

- ^ Midrash Tanhuma Beha’aloscha 16.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 28b.

- ^ Mishnah Sanhedrin 1:6. Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 2a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 36b.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 75b.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 19:10.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 17a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 17a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 38a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 7a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 87a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 64b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Asher Dicker, Nasanel Kasnett, Noson Boruch Herzka, Reuvein Dowek, Michoel Weiner, Mendy Wachsman, and Feivel Wahl; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 30, page 64b3. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-57819-648-5.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 92:7.

- ^ Mishnah Sotah 1:7–9. Babylonian Talmud Sotah 9b.

- ^ Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Positive Commandments 57, 58, 59; Negative Commandments 119 & 122. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, 1:67–71; 2:111, 113. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, 4:79–93. Jerusalem: Feldheim Pub., 1988. ISBN 0-87306-457-7.

- ^ Numbers 9:11.

- ^ Numbers 9:11.

- ^ Numbers 9:12.

- ^ Numbers 9:12.

- ^ Numbers 10:9.

- ^ Menachem Davis. The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation, 580. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-697-3.

- ^ Davis, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, at 243.

- ^ Menachem Davis. The Interlinear Haggadah: The Passover Haggadah, with an Interlinear Translation, Instructions and Comments, 68. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2005. ISBN 1-57819-064-9. Joseph Tabory. JPS Commentary on the Haggadah: Historical Introduction, Translation, and Commentary, 104. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8276-0858-0.

- ^ Davis, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, at 377, 485.

- ^ Davis, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, at 40.

- ^ Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, 139, 154. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2003. ISBN 0-916219-20-8. Davis, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, at 358, 399, 480, 487.

- ^ Davis, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, at 344.

- ^ Menachem Davis. The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for Weekdays with an Interlinear Translation, 16–17. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-686-8.

- ^ Hammer, at 14.

- ^ Reuven Hammer. Entering Jewish Prayer: A Guide to Personal Devotion and the Worship Service, 6. New York: Schocken, 1995. ISBN 0-8052-1022-9.

- ^ Numbers 8:1–4; Zechariah 4:2–3.

- ^ Zechariah 4:10.

- ^ Zechariah 4:6.

- ^ Numbers 8:6–7

- ^ Zechariah 3:3–5.