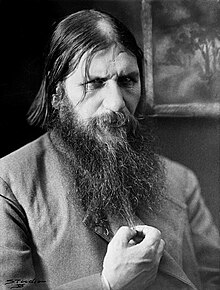

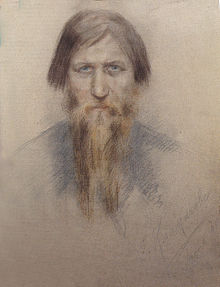

Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Rasputin | |

|---|---|

Grigori Rasputin | |

| Born | 21 January 1869 |

| Died | 30 December 1916 (aged 47) |

| Cause of death | Homicide |

| Occupation(s) | peasant, wanderer, healer, advisor |

| Spouse | Praskovia Fedorovna Dubrovina |

| Children | Dmitri (1895–1937) Matryona (1898–1977) Varvara (1900–1925) |

| Parent(s) | Efim Vilkin Rasputin Anna Parshukova |

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (Russian: Григорий Ефимович Распутин, IPA: [ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲɪj jɪˈfʲiməvʲɪtɕ rɐˈsputʲɪn]; baptized on 22 January [O.S. 10 January] 1869 – murdered on 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916[1]) was a Russian peasant, mystic, faith healer and private adviser to the Romanovs. He became an influential figure in Saint Petersburg after August 1915 when Tsar Nicolas II took command of the army at the front.

There is much uncertainty over Rasputin's life and the degree of influence he exerted over the Tsar and his government.[2] Accounts are often based on dubious memoirs, hearsay and legend.[note 1] While his influence and role may have been exaggerated, historians agree that his presence played a significant part in the increasing unpopularity of the Tsar and Alexandra Feodorovna his wife, and the downfall of the Russian Monarchy. Rasputin was killed as he was seen by left and right to be the root cause of Russia's despair during World War I.[4]

Early life

Grigori Rasputin was born the son of a well-to-do peasant in the small but prosperous village of Pokrovskoye in the Tobolsk guberniya (now Yarkovsky District in the Tyumen Oblast) in the immense West Siberian Plain. The parish register contains the following entry for January 9, 1869: "In the village of Pokrovskoe, in the family of the peasant Yefim Yakovlevich Rasputin and his wife, both Orthodox, was born a son, Grigory."[6] The next day he was baptized and named after Gregory of Nyssa, whose feast day is on 10 January.[7]

Grigori was the fifth of nine children. He never attended school; according to the census of 1897 almost everybody in the village was illiterate.[8] In Pokrovskoye the young Rasputin was regarded as an outsider, but one endowed with mysterious gifts. "His limbs jerked, he shuffled his feet and always kept his hands occupied. Despite physical tics, he commanded attention."[9] The little that is known about his childhood was passed down by his daughter Maria.[10] On February 2, 1887, Rasputin married the three-years-older Praskovia Fyodorovna Dubrovina. The couple had three children: Dmitri, Varvara and Maria; two earlier sons died young. In 1892 [11] Rasputin abruptly left his village, his wife, children and parents. He spent several months in a monastery in Verkhoturye; Spiridovich suggests after the death of a child,[12] but the monastery was enlarged in those years to receive pilgrims.[13] Outside the monastery lived a hermit by the name of Brother Makary. Makary had a strong influence on Rasputin, which led to Grigori giving up drinking, smoking, and eating meat. When he arrived home he had learned to read and write and had become a zealous convert.

Turn to religious life

Rasputin's claimed vision of Our Lady of Kazan turned him towards the life of a religious mystic. Around 1893 he travelled to Mount Athos, but left shocked and profoundly disillusioned, as he told Makary.[14]

By 1900 he was identified as a strannik, a wandering pilgrim,[15] although Rasputin always went home to help his family with the harvest. He was regarded as a starets and a yurodiviy (holy fool)[16] by his followers, who also believed him to be a psychic and faith healer.[2] Rasputin himself did not consider himself to be a starets.[17] Rasputin spoke an almost incomprehensible Siberian dialect[18] and seldom preached or spoke in public.

In 1903 he spent some time in Kiev where he visited the Monastery of the Caves. In Kazan he attracted the attention of the bishop and members of the upper class.[19] Rasputin then traveled to the capital to meet with John of Kronstadt. Pierre Gilliard writes that Rasputin arrived in 1905,[20] M. Nelipa thinks Autumn 1904, Iliodor believed it was already in December 1903.[21] He carried an introduction to Ivan Stragorodsky, the rector of the Theological Faculty.[22] Rasputin stayed at Alexander Nevsky Lavra; there he met with Hermogenes and Theophanes of Poltava who was amazed with his psychological perspicacity. He was invited by Milica of Montenegro and her sister Anastasia, who were interested in Persian mysticism,[23] spiritism and occultism. Milica presented Rasputin to tsar Nicholas and his wife Alexandra on 1 November 1905 (O.S.).[24]

Prior to his meeting with Rasputin, the Tsar had to deal with the Russo-Japanese War, Bloody Sunday, the Revolution of 1905, bombs and a nation-wide railway strike. In a city without electricity the Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias was forced on the 17th by Sergei Witte to sign the October Manifesto, to agree with the establishment of the State Duma and give up part of his unlimited autocracy.[25] For the next six months Witte was the Prime Minister, but the real ruler of the country was general Dmitri Trepoff.

Healer to Alexei

In October 1906, at the request of the Tsar, Rasputin paid a visit to the wounded daughter of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. A few weeks before, 29 people had been killed after a bomb attack, including one of Stolypin's children.[26] A few months later,

... on December 15, Rasputin petitioned the Tsar, seeking to legally change his name. Grigory explained that six families in Pokrovskoye bore the surname Rasputin, and this was producing "every sort of confusion." Rasputin asked Nicholas "to end this confusion by permitting me and my descendants to take the name Rasputin-Novyi (Новый)," which means "Rasputin-New" or the "New Rasputin."[27]

In April 1907 Rasputin was invited again to Tsarskoye Selo, this time to see tsarevich Alexei. The boy had received an injury which caused him painful bleeding. It was not publicly known that the heir to the throne had hemophilia B, a disease that was widespread among European royalty.[28] When doctors could not supply a cure, the desperate Tsarina looked for other help; she had lost her mother, her brother, her younger sister when she was young. Rasputin was said to possess the ability to heal through prayer and was able to calm the parents and to give the boy some relief, in spite of the doctors' prediction that he would die. On the following day the Tsarevich showed significant signs of recovery.[29]

In early October 1912, during a particularly grave crisis in Spała, in Russian Poland, the Tsarevitch received the last sacrament. The desperate Tsarina turned to her best friend, Anna Vyrubova,[30] to secure the help of the peasant healer, who at that time was out of favor. The next day, on 9 October Rasputin responded and sent a short telegram, including the prophecy: "The little one will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much."[31] Alexandra, like Rasputin obsessed with religion,[18] believed that he had cured her son through the power of prayer.[32]

It has been claimed that Rasputin's apparent healing powers arose from his use of hypnosis, but Rasputin was not interested in this practice before 1913 and his teacher was expelled from St. Petersburg.[33] Rasputin's enemies suggested that he secretly drugged Alexis[18] with Tibetan herbs which he got from the quack doctor Peter Badmayev. For Maria Rasputin it was magnetism.[34] For Greg King these explanations fail to take into account those times when Rasputin healed the boy, despite being 2600 km (1650 miles) away. For Fuhrmann these ideas on hypnosis and drugs flourished because the imperial family lived such isolated lives.[35] (They lived almost as much apart from Russian society as if they were settlers in Canada.[35]) For Moynahan, "There is no evidence that Rasputin ever summoned up spirits, or felt the need to; he won his admirers through force of personality, not by tricks."[36]

Controversy

Even before Rasputin's arrival the upper class of St Petersburg had been widely influenced by mysticism. Individual aristocrats were reportedly obsessed with anything occult.[37] Alexandra had been meeting a succession of Russian "holy fools" hoping to find an intercessory with God.[38] Papus had visited Russia three times, in 1901, 1905, and 1906, serving the Tsar and Tsarina both as physician and occult consultant.[39] While fascinated by Rasputin, who was favoured by the Imperial family, the ruling class of St Petersburg became envious and turned against him. Around 1910 the press started a campaign against Rasputin, claiming he paid too much attention to young girls and women. Theofan lost his interest in Rasputin and Stolypin wanted to ban him from the capital. In the next year the Tsar instructed Rasputin to join a group of pilgrims.[40] From Odessa they sailed to Constantinople, Patmos, Cypres and Beirut. Around Lent 1911 he paid a visit to Jerusalem and the Holy Land.[41] On his way back he visited Iliodor who gathered huge crowds in Tsaritsyn.

In early 1912 Hermogen, who told Rasputin to stay away from the palace, started rumours that Rasputin had joined the Khlysty, an obscure Christian sect with strong Siberian roots. Iliodor, hinting that Rasputin was Alexandra's paramour, showed Makarov a satchel of letters, one written by the Tsarina and four by her daughters.[42] The given [43] or stolen[44] letters were handed to the Tsar.[45] Rodzianko requested Rasputin to leave the capital.[46] When Vladimir Kokovtsov became prime minister he asked the Tsar permission to authorize Rasputin's exile to Tobolsk, but Nicholas refused. "I know Rasputin too well to believe all the tittle-tattle about him."[47] Kokovtsov offered Rasputin 200,000 rubles, a substantial amount of money when he would leave the capital. Rasputin had become one of the most hated people in Russia.[48]

There is little or no proof that he was a member of the Khlysty,[50] but Rasputin does appear to have been influenced by their practices.[51] He accepted some of their beliefs, for example those regarding sin as a necessary part of redemption.[52] He believed that those deliberately committing fornication and then repenting bitterly, would be closer to God.[53] Suspicions that Rasputin, a good dancer,[54] was one of the Khlysty tarnished his reputation right until the end of his life. Recently found documents (a 500-page document archive provided by Mstislav Rostropovich and investigated by Edvard Radzinsky)[55] suggest that accusations about Rasputin's sexual dissoluteness were false.[56] The basis for the denunciation of Rasputin as a Khlyst was mixed bathing, a perfectly usual custom among the peasants of many parts of Siberia.[57][58]

After the Spala accident, when the Tsarevich fell and became seriously ill,[59] Rasputin regained influence at court and also in church affairs. His position as an intermediary had been dramatically validated.[60] An attempt was made to push through the Synod an authorization to ordain Rasputin a priest,[35] but the Holy Synod frequently attacked Rasputin, accusing him of a variety of immoral or evil practices. Rasputin was variously accused of being a heretic, an erotomaniac or a pseudo-khlyst.[61] On 21 February 1913 Rodzianko ejected Rasputin from the Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan shortly before the celebration of 300 years of the Romanov rule over Russia. He had established himself in front of the seats which Rodzianko, after great difficulty, had secured for the Duma.[62]

Rasputin's behaviour was discussed in the Fourth Duma,[63] and in March 1913 the Octobrists, led by Alexander Guchkov and President of the Duma, commissioned an investigation.[64] Worried with the threat of a scandal, the Tsar asked Rasputin to leave for Siberia. Nicholas accepted investigations on Rasputin being a Khlyst,[65] but quickly decided to criticize the politicians [66] and the investigations were stopped.[18][35][67] He and his wife referred to Grigori as our "Friend" and a "holy man", emblematic of the trust that the family had placed in him. "Anyone bold enough to criticize Rasputin found only condemnation from the Tsarina."[68] In December 1913 Rasputin and his wife were invited to the Livadia Palace.[69] The Tsar dismissed Kokovtsov on 29 January 1914.[70] He was replaced by the absent minded Ivan Goremykin, and Pyotr Bark. According to Pavel Milyukov, in May 1914 Rasputin had become an influential factor in Russian politics;[71] Alexander Krivoshein was the most powerful figure in the Imperial government.[72]

Assassination attempt

In 1914 Rasputin travelled with his father, who had been visiting him, from the capital to Pokrovskoye.[73] After dining on the afternoon of Sunday 12 July [O.S. 29 June] 1914,[74] Rasputin went out from the house; coming from the telegraph office he was suddenly attacked by one Khionia Guseva. This woman who had her face concealed with a black kerchief approached him, and then jerked out a dagger.[75] She stabbed Rasputin in the stomach, just above the navel, exposing his entrails. Rasputin fell, covered with blood and was brought into his house. After ten hours a doctor arrived in a troika and operated on him in the middle of the night. On 3 July, Rasputin was transported by boat to Tyumen for treatment, accompanied by his family. The Tsar sent his own physician[76] and after a laparotomy and almost seven weeks in the hospital, where he had to walk around in a gown, unable to wear ordinary clothes,[77] Rasputin recovered.[78] On August 17, 1914 Rasputin, who believed Iliodor and Vladimir Dzhunkovsky had organized the attack, [79] left the hospital. His daughter Maria records that he was never the same man afterwards.[80][81] According to Maria Rasputin started to drink dessert wines.[82] [83]

After the attack, the former monk Iliodor, once a leader in the Union of the Russian People, fled all the way around the Gulf of Bothnia to Oslo. Guseva, a fanatically religious woman, had been his adherent in earlier years "denied Iliodor's participation, declaring that she attempted to kill Rasputin because he was spreading temptation among the innocent."[84] The local procurator decided to suspend any action against Iliodor for undisclosed reasons,[85] Guseva was locked up in a madhouse in Tomsk and a trial was avoided.[86]

Most of Rasputin's enemies had by now disappeared. Stolypin was dead, Count Kokovtsov fallen from power, Theofan exiled, Hermogen [illegally] banished and Iliodor in hiding.[87]

Yar restaurant incident

In January 1915 Stepan Petrovich Beletsky, head of the police, exercised 24-hour surveillance of him and his apartment.[88] Two sets of four detectives were attached to his person,[89] two were to act undercover.[90] Reports from Ochrana spies from 1 January 1915 - the famous "staircase notes" - provided evidence about Rasputin's lifestyle, that was given to the Tsar in an attempt to convince him to break with Rasputin.[91] In reading it the Tsar observed that on the day and hour at which one of the acts mentioned in the document were alleged to have taken place Rasputin had actually been at Tsarskoe-Selo.[92] For Bernard Pares, it was taken that police were the enemies of Rasputin, and that the many stories which reached the public were simply their machinations.[93]

On 25 March 1915 (O.S.) Rasputin left for Moscow by train, accompanied by his guards. On the next evening he is said, whilst inebriated, to have opened his trousers and waved his genital in front of shocked diners in the Yar restaurant.[94] Nelipa argues that this story was fabricated by Vladimir Dzhunkovsky in order to discredit Rasputin.[95] According to his daughter he was petrified of going to unknown places after the attack by Guseva. Partying with an 78-year-old woman with whom he stayed and only left her house to attend a church is not very credible. Besides he seems to have been accompanied with two journalists, people he usually did not trust. An unreliable report was presented a few months later; the police did not interview any witness in the restaurant. Dzhunkovsky and Stepan Beletsky verified later that Rasputin never visited the Yar restaurant.[96][citation needed]

World War I

After the First Balkan War the Balkan allies planned the partition of the European territory of the Ottoman Empire among them. During the Second Balkan War the Tsar tried to stop the conflict, since Russia did not wish to lose either of its Slavic allies in the Balkans. Rasputin warned the Tsar not to get involved and promoted peace negotiations. It seems Rasputin became the enemy of Grand Duke Nicholas, a panslavist, his brother Peter and their wives Milica and Anastasia of Montenegro, eager to go in war and push the Austrians out of the Balkans.[97]

Shortly before the outbreak of World War I, Rasputin spoke out against Russia going to war with Germany. He begged the Tsar to do everything in his power to avoid war.[98] From the hospital Rasputin sent quite a few telegrams to the court expressing his fears for the future of the country. "If Russia goes to war, it will be the end of the monarchy, of the Romanovs and of Russian institutions."[99] On 17 July the Tsar ordered full mobilization. Russia expected the war would last until Christmas,[100] but after a year the situation at the Eastern front had become disastrous: more than 1,5 million Russian soldiers had died. When the German army occupied Warsaw in August 1915 the situation looked extremely grave, because of a shortage in weapons and munitions due to bad train connections. As a result the Russian army had to withdraw (Great Retreat). Vladimir Sukhomlinov left on charges of abuse of power and treason. It caused a scandal. There was a shortage of food and high prices and the Russian people blamed all on "dark forces" or spies for and collaborators with Germany; in May 1915 shops in Moscow, owned by foreigners, were attacked.[101]

On the eve of the war the government and the Duma were hovering round one another like indecisive wrestlers, neither side able to make a definite move.[102] The Great Retreat made the political parties more cooperative and practically formed into one party. When the Tsar announced his departure for the front in Mogilev, the Progressive Bloc was formed, fearing Rasputin's influence over tsarina Alexandra would increase.[103] Alexandra hated the Duma because of its discussion of Rasputin.[104] On August 19, 1915, after an unsuccessful attempt to discredit Rasputin and the Tsarina in a newspaper, prince Vladimir Orlov [18] and Vladimir Dzhunkovsky were discharged from their posts. The Tsar then pronounced the affair between Rasputin and the Romanovs to be a private one, closed to debate.[105]

Tsar Nicholas took supreme command of the Russian armies on August 23, 1915 (O.S.), hoping this would lift morale. He was undoubtedly led to this fateful decision by the insistence of the Tsarina and of Rasputin[106] who, according to Maklakov, seem to have been the only ones who supported the Tsar in his decision. "Having one man in charge of the situation would consolidate all decision making."[107] However, there proved to be dire consequences for himself as well as for Russia. All the ministers, even Ivan Goremykin, realized that the change would put Rasputin in charge and threatened to resign.[108] In September the Imperial Duma was sent into recess and would not gather again until February 1916. Vasily Maklakov published his famous article, describing Russia as a vehicle with no brakes, driven along a narrow mountain path by a "mad chauffeur", a reference to the Tsar.[109]

Government

While seldom meeting with Alexandra personally after the debate in the Duma, Rasputin had become her personal adviser through daily telephone calls or meetings with Vyrubova. This was especially the case after August 1915[111] when the Emperor left Petrograd for Stavka at the front, leaving his wife Alexandra Feodorovna to act in his place. It appears that Rasputin's personal influence over the Tsarina became so great that it was he who ordered the destinies of Imperial Russia, while she compelled her weak husband to fulfill them.[112] According to Fuhrmann a symbiotic relationship developed between the Tsarina and Rasputin, in which "each fed from the other".[113] According to Pierre Gilliard "her desires were interpreted by Rasputin, they seemed in her eyes to have the sanction and authority of a revelation."[114]

The Tsar had resisted the influence of Rasputin for a long time. At the beginning he had tolerated him because he dare not weaken the Tsarina's faith in him - a faith which kept her alive. He did not like to send him away, for if Alexie Nicolaievich had died, in the eyes of the mother he would have been the murderer of his own son.[92]

Late 1915 Alexandra and Rasputin advised the Tsar in military strategies in Rumania and around Riga where the Germans and Austrians were stopped. Rasputin was opposed to the plan to send the old Goremykin away. It seems the two also dominated the Holy Synod and when John of Tobolsk was glorified Rasputin, Lili Dehn and Anna Vyrubova went off to the city of Tobolsk.[citation needed] At the beginning of 1916 Alexei Khvostov and Iliodor concocted a plan to kill Rasputin. Khvostov accused Rasputin working for a separate peace and suggested that Alexandra and Rasputin were German agents or spies.[115] Evidence that Rasputin actually worked for the Germans is flimsy at best.[116] According to Kerensky people around Rasputin (his secretaries) were interested in strategic information.[117] Rasputin himself never estimated money and gave it away as soon he had received it.[118] He had built up a reputation of being at once a generous and a disinterested man. Besides alms Rasputin spent large sums in restaurants, cafes, music halls and in the streets...[58]

Rather paranoid, Rasputin went to Alexander Spiridovich, head of the palace police. He seems to have been constantly in a state of nervous excitement. Khvostov had to resign in March 1916; Boris Stürmer was appointed in his place. In the same month Minister of War Alexei Polivanov, who in his few months of office brought about a recovery of the efficiency of the Russian army, was removed and replaced by Dmitry Shuvayev. The Minister of Foreign Affairs Sazonov, who had pleaded for an independent and autonomous Russian Poland, was replaced in June. In July Aleksandr Khvostov, not in good health, was appointed as Minister of Interior. In September Alexander Protopopov, had been appointed as his successor. Protopopov, an industrialist and landowner, raised the question of transferring the food supply from the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of the Interior. A majority of the zemstvo leaders announced that they would not work with his ministry. His food plan was universally condemned. In October Sukhumlinov was released from prison on instigation of Alexandra, Rasputin and Protopopov. This time the public was outraged.[119] Protopopov was a questionable politician; he showed signs of mental disorder, his ideas (or speeches) had no coherence. A strongly prevailing opinion that Rasputin was the actual ruler of the country was a great psychological importance.[120]

The Duma

On 1 November (O.S.) the government under Boris Stürmer [122] was attacked by Pavel Milyukov in the State Duma, not gathering since February. In his speech he spoke of "Dark Forces", to avoid the name of Rasputin and highlighted numerous governmental failures, concluding that Stürmer's policies placed in jeopardy the Triple Entente. After each accusation he asked "Is this stupidity or is it treason?", and the listeners answered "Stupidity!", "Treason!", or "Both!" A few hours before Alexander Kerensky had called the ministers "hired assassins" and "cowards" and said they were "guided by the contemptible Grishka Rasputin!"[123] Stürmer, followed by all his Ministers, walked out. In a speech in the Duma Ivan Grigorovich and Dmitry Shuvayev declared they had confidence in the Russian people, the navy and the army. Stürmer and Protopopov asked in vain for the dissolution of the Duma.[124] Grand Duke Alexander and his brother George Mikhailovich requested the Tsar to fire Stürmer. Also Sir George Buchanan attempted to influence the Tsar, but the latter did not appreciate the British ambassador's advice.[125]

Grand Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich, according to M. Nelipa one of the key players,[126] prince Lvov and general Mikhail Alekseyev attempted to persuade Nicholas to send the Empress away either to the Livadia Palace in Yalta or to England.[127] Also for Rodzianko it was clear Alexandra should not be allowed to interfere in state affairs until the end of the war; she treated her husband as if he were a little boy, quite incapable of taking care of himself. Zinaida Yusupova, Alexandra's sister Elisabeth, Grand Duchess Victoria and the Tsar's mother tried to influence the Emperor or his stubborn wife[18] to remove Rasputin, but without succes.[128] In short, there was practically no one ... who did not see the need for a fundamental change in the structure of the government,[121] but the Tsar and his wife were convinced of upholding their autocracy, against the influence of the Duma, and not accessible for any advise.

On 19 November the popular Vladimir Purishkevich, much opposed to the October Manifesto in 1905, and one of the founders of the Black Hundreds, held a two-hour speech the Duma. The trouble was that the different Ministries did not cooperate. The government was the problem. The monarchy - because of what he called the 'ministerial leapfrog' - had become fully descredited.[129]

The Tsar's ministers who have been turned into marionettes, marionettes whose threads have been taken firmly in hand by Rasputin and the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna—the evil genius of Russia and the Tsarina ... who has remained a German on the Russian throne and alien to the country and its people.[130]

Purishkevich, a buffoon character, stated that Rasputin's influence over the Tsarina had made him a threat to the empire: "... an illiterate moujik shall govern Russia no longer!"[131] “While Rasputin is alive, we cannot win”.[132]

Prince Felix Yusupov was impressed by the remarkable speech.[133] Two days later he visited Purishkevich, who quickly agreed to participate in the murder of Rasputin. First Yusupov approached the lawyer Vasily Maklakov, who agreed to advise Felix.[134] Then he approached Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an army officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, recuperating from injuries, and friend to his mother.[135] Also Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich received Yusupov's suggestion with alacrity, and his alliance was welcomed as indicating that the murder would not be a demonstration against the [Romanov] dynasty.[136] His father, Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia, had tried to persuade the Tsar, to change his policy[137] and accept a new constitution in order to save the monarchy. In the Russian Constitution of 1906 the Tsar retained an absolute veto over legislation, as well as the right to dismiss the Duma at any time, for any reason he found suitable.

Trepov and Protopopov

On 10 November (O.S.) Alexander Trepov had been appointed as the new prime minister, but had made the dismissal of Alexander Protopopov, who obviously had problems making up his mind and decide, an indispensable condition of his accepting the presidency of the Council. The Tsarina tried to save Protopopov in his influential position in the ministry of interior. Both Trepov and Alexandra traveled to Stavka; the latter to convince her husband to have the exceedingly nervous Protopopov staying. Rasputin and Vyrobova each sent five telegrams to support her.[138] Trepov threatened to resign. On 17 November (O.S.) Nikolai Pokrovsky was appointed minister of foreign affairs. On 2 December [139] Pokrovsky said that Russia would never sign a peace treaty with the Central Powers, which caused a storm of applause in the Duma. The appointment of Protopopov wasn't approved until 7 or 8 December 1916. Trepov, having failed to eliminate Protopopov, tried to bribe Rasputin in the next days.[140] With the help of general A.A. Mosolov,[141] his brother-in-law, Trepov offered a substantial amount of money, a bodyguard and a house to Rasputin, when he would leave politics.[142]

From 1905-1917 the Council of Ministers collectively decided the government's policy, tactical direction, and served as a buffer between the Emperor and the national legislature. The politicians tried to bring the government under control of the Duma.[143] For the Octobrists and the Kadets, the liberals in the parliament, Rasputin, who believed in autocracy and absolute monarchy, was one of the main obstacles. Alexander Guchkov had come to the painful conclusion the situation could only improve when the Tsar was sent away.[144] The Progressive Bloc supported a resolution that the Tsar was to be replaced by his son Alexei, and the Grand Duke Michael was to be the regent. Alexandra suggested to her husband to expel Prince Lvov, Milyukov, Guchkov and Polivanov to Siberia.[145] Protopopov banned in the end of December 1916 the zemstvos, the local government, from meeting without the police in attendance.[146] "To the Okhrana it was obvious that the liberal Duma project was superfluous, and that the only two options left were repression or a social revolution."[147]

Rasputin apparently feared that he would die before the end of the year.[148] It seems he accepted his destiny.[149] According to Simanovich he burned his correspondence and moved money to his daughters from his bank account on 13 December.[150] Simanovich also published a strangely prophetic letter "The Spirit of Gregory Efimovich Rasputin of the village of Pokrovskoe", intended for the Tsar.[151] According to Edvard Radzinsky the prophecy is not by Rasputin.[149][152]

On Friday afternoon, December 16, Rasputin returned from the bathhouse at 3 p.m. Around 8 p.m. he told Anna Vyrubova, who presented him a small icon, signed and dated at the back by the Tsarina and her daughters,[153] of a proposed midnight visit to Yusupov in his palace. Protopopov, a late visitor that evening to Rasputin's flat, had begged him not to go out that night.[154] Nelipa thinks what happened next was intentionally timed; both Grand Duke Dmitry and Purishkevich, assisting at the front, had arrived in the city. The recess (until 14 January) would eliminate the otherwise predictable uproar from any of the delegates at the Tauride Palace, had the murder been arranged a few days earlier.[155]

Murder

The murder of Rasputin has become something of a legend, some of it invented, perhaps embellished or simply misremembered. There are very few facts between the night he disappeared and the day his corpse was dredged up from the river.

Assassination

A few days before the night of 16/17 December (O.S.) Rasputin had been invited to the Yusupov palace[156] at an unseemly hour, intimating Yusupov's attractive wife, Princess Irina, would be back from Koreiz. Yusupov, who had visited Rasputin regularly in the past few weeks or months for treatment, went with Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert to Rasputin's apartment, then they drove to the palace, recently refurbished. A sound-proof room in the basement in the east wing had been specially prepared for the crime. According to Purishkevich they had placed four bottles, containing Marsala, sherry, a cherry liquor and Madeira in a window. Waiting on another floor were the fellow conspirators: the young Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, Purishkevich and Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin. It is not sure there were any women invited for what Yusupov would call a few days later a housewarming party.

According to Yusupov he offered petit fours, laced with a large amount of cyanide to Rasputin. According to Purishkevich the Prince climbed the stairs three times, as Rasputin refused the cakes or to drink anything. Maria Rasputin asserts that, after the attack by Guseva, her father suffered from hyperacidity and avoided anything with sugar.[157] In fact, not only his daughter but also his former secretary Simanotvich express doubt that he was poisoned at all.[158]

Yusupov played his guitar and sang a few gypsy ballads at the request of Rasputin, who was fond of gypsy music.[159] Purishkevich does not mention this, although he writes he could hear bottles were opened. Paléologue seemed to know they discussed spirituality and occultism.[160] After an hour, still waiting for Rasputin to collapse, Yusupov became anxious about the possibility that Rasputin might live until the morning, leaving the conspirators no time to conceal his body. Yusupov went upstairs to consult the others and determined to finish the job, he came back with a revolver. Rasputin was severely hit by a bullet that entered his left chest and penetrated the stomach and the liver; a second entered the left back soon after the first and penetrated the kidneys.[161] Purishkevich writes Yusupov had missed and did not succeed killing Rasputin.

At some time, when three of his fellow conspirators had left, Yusupov went down to check on the body and Rasputin seems to have opened his eyes and lunged at him. He is supposed to have grabbed Yusupov, tore an epaulette off his tunic and attempted to strangle him. (Yusupov was keen on describing Rasputin as a monster, that did not die from poison. So he could hide the real course of events, and become the "Savior of Russia").[162] Rasputin climbed the stairs to the ground floor stumbling in the courtyard. At that moment, according to Purishkevich, he fired four times (but missed twice) at Rasputin, who fell into the snow. A nervous Yusupov clubbed his victim severely.

A curious policeman on duty on the other side of the Moika who had heard the shots, rang at the door but was sent away. Half an hour later another police man arrived and Purishkevich invited him into the palace. Purishkevich boasted he had shot Rasputin, and aware of his mistake he asked to policemen to keep it quiet for the sake of the Tsar.[163] However, this policeman told his superiors everything he had heard and seen.[164]

They had planned to burn Rasputin’s possessions; Sukhotin put on Rasputin’s fur coat, his rubber boots, and gloves. He left together with Dmitri Pavlovich and Dr. Lazovert in Purishkevich' car,[164] suggesting Rasputin had left the palace alive.[165] Because Purishkevich' wife refused to burn the fur coat and the boots in her small fireplace in Purishkevich' ambulance train, the conspirators went back to the palace with the mentioned items. When the body was wrapped in a curtain, the conspirators drove in the direction of Krestovsky island[166] and at about 5am threw the corpse from a bridge into the Malaya Nevka River in an ice-hole. They forgot to attach weights so that the body would sink deep, dropped his fur coat over the railing with the chains, and drove back, without noticing one of Rasputin's goloshes, a rubber boot (size 10), was stuck between the piles of the bridge.[167]

The date of Rasputin’s death is sometimes recorded as being 16 December 1916 (Old Style) or thirteen days later on 29 December 1916 using New Style,[note 2] but the murderers left after midnight to Rasputin's apartment, when his guards were gone. The initial attempts to kill Rasputin began in the early morning and it is supposed he died between 3 and 4 o'clock.[168]

Days following

Rasputin's disappearance was reported by his daughter early that morning to Vyrubova. When Vyrubova spoke of it to the Empress, Alexandra pointed out that Princess Irina was absent from Petrograd. When Protopopov mentioned the story reported by the police at the Moika, they began to believe that Rasputin had been lured into an ambush. On the Empress' orders, a police investigation commenced and traces of blood were discovered on the steps to the backdoor of the Yusupov Palace. The Tsarina had refused to meet the two, but said they could explain to her what had happened in a letter. Purishkevich assisted them and left the city to the front at ten in the evening. Prince Felix attempted to explain the blood with a story that by accident one of his dogs was shot by Dmitri. A Uhlenhuth test showed the blood was of human origin. Then Prince Yusupov and Grand Duke Dmitri were placed under house arrest in the Sergei Palace.

When traces of blood were detected on the parapet of the Bolshoy Petrovsky bridge on Sunday afternoon, one of his boots was found. It was late in the afternoon, but the police knew now where to investigate. On Monday, 19 December (O.S.),[171] Rasputin's beaver furcoat and the body were discovered 140 meters away from the bridge in the frozen river.[172] The corpse was taken to the desolate Chesme or Chesmensky Almshouse. An autopsy on the thawed corpse by Kossorotov in a poorly lighted mortuary room on the evening of 20 December[169] established that the cause of his instant death was the third bullet in his brain.[173] with strong evidence there was an exit wound at the back of the head.[174] The second bullet was extracted. The first and third shots were made at close range,[175] but had exited his body. Zharov concluded the three bullet-holes were of different sizes.[176] There was alcohol (cognac according to Kossorotov) in his body, no water found in his lungs[177] and no cyanide in his stomach.[178][179] There were a number of injuries, all of them caused after his death. His right cheek was shattered when the body was thrown from the bridge.[180] Kossorotov found that Rasputin’s genitals were crushed.[169]

"There is no evidence that Rasputin swallowed water after being pushed into the Neva or that he had freed his arm to make the sign of the cross."[181] The "drowning story" had become a fixed part of the legend. Rasputin was already dead when thrown into the water.[182] On 21 December Rasputin's body was taken in a zinc coffin from the Chesme Church[183] to be buried in a corner on the property of Vyrubova [18] and adjacent to the palace.[184] The burial at 8.45 in the morning was attended by the Imperial couple with their daughters, Vyrubova, her maid, and a few of Rasputin's friends, as Lili Dehn. It is not sure if the two daughters of Rasputin were present, although Maria Rasputin claims she was there.[185] Later that day Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich wrote the Tsar to close the case. The next day [186] the Tsar sent Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, and Yusupov in exile, without a trial. Purishkevich was already on his way to the front. On 23 December the police were ordered to stop her inquest.[187]

On 27 December the hesitating Nikolai Golitsyn became the successor of Trepov, who was allowed to retire. Also Pavel Ignatieff, Alexander Alexandrovich Makarov and Dmitry Shuvayev were replaced.

"On the Russian front," Paléologue wrote, "time is not working for us now. The public does not care about the war. All the government departments and the machinery of administration are getting hopelessly and progressively out of gear. The best minds are convinced that Russia is walking straight into the abyss. We must make haste."[188]

More and more people came to the conclusion that the problem was not Rasputin but the weak-willed Emperor. The struggle between the Tsar and the Duma became more bitter than ever.

In the seventeen months of the `Tsarina's rule', from September 1915 to February 1917, Russia had four Prime Ministers, five Ministers of the Interior, three Foreign Ministers, three War Ministers, two Ministers of Transport and four Ministers of Agriculture. This "ministerial leapfrog", as it came to be known, not only removed competent men from power, but also disorganized the work of government since no one remained long enough in office to master their responsibilities.[189]

After the February Revolution, when the monarchy was deserted by all the élites of the old society, the landowners, the army officers, the industrialists, and politicians of the Duma as Vasily Shulgin, the Tsar resigned in the company of Vladimir Freedericksz and Grand Duke Nicholas on 2 March 1917 (O.S.). According to Figes ".. the whole of 1917 could be seen as a political battle between those who saw the revolution as a means of bringing the war to an end and those who saw the war as a means of bringing the revolution to an end."[190]

The investigation on Rasputin had been stopped on 4 March (O.S.) by Kerensky and extended an amnesty to the three main conspirators. All the movements of the imperial family were restricted on the 8th as the grave of Rasputin had become a place of worship for the Tsarina and her daughters.[191] After Rasputin grave site was found the coffin was transported to the town hall, where a curious crowd gathered, and secured under guard over night on 8 March. According to Moynahan:

Rasputin’s face was found to have turned black, and an icon was found on his chest. It bore the signatures of Vyrubova, Alexandra, and her four daughters. The body was put into a packing case that once held a piano and was driven in secret to the imperial stables in Petrograd. The next day it was loaded onto a truck and taken out of Petrograd on the Lesnoe Road.[192]

Authors do not agree what happened on the night of 10/11 March after the truck drove on its way north in the direction of Piskarevka. The story goes the truck broke down or the snow forced them to stop. The corpse is supposed to be taken into a field in the Vyborgsky District and burned.[193] According to Nelipa and Moe the cremation was carried out in the boiler shop of the Saint Petersburg State Polytechnical University in the middle of the night, without leaving a single trace.[194]

Recent evidence

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by 204.186.255.22 (talk | contribs) 10 years ago. (Update timer) |

The official police report, with details gathered in two days, and stopped with the idea the murder was solved, is unconvincing. What is left are the memoirs of the murderers, the 29-years-old Felix Yusupov and 47-years old Vladimir Purishkevich. "Unfortunately, after the Soviets came to power, many of the documents that formed part of the official secret investigation have either been destroyed, or have disappeared."[195]

The theatrical details on the murder given by Felix Yusupov have never stood up to scrutiny. He changed his account several times; the statement given to the Petrograd police, the accounts given whilst in exile in the Crimea in 1917, his 1927 book, and finally the accounts given under oath to libel juries in 1934 and 1965 all differ to some extent, and until recently no other credible, evidence-based theories have been available.

When asked [in 1965] by his attorney as to his motive killing Rasputin, he announced that he was motivated by his "distaste for Rasputin's debaucheries". This represented a major shift from his argument since 1917 that emphasized that he was motivated solely by patriotism for Russia.[196]

Yusupov's role in the murder has been called into question being "consumed by the thought that "not a single important event at the front was decided without a preliminary conference" between Alexandra and Rasputin.[197] Besides the murderers did not know what he had on, a beige or a blue shirt,[81][198] and where Rasputin’s wounds were. Purishkevich said he fired at Rasputin from behind at a distance of twenty paces and hit Rasputin in the back of the head. There is no photo of the rear of Rasputin’s head.[199] They both denied any women were invited to the palace that night.

According to the unpublished 1916 autopsy report by Professor Dmitry Kossorotov, as well as subsequent reviews by Dr. Vladimir Zharov in 1993 and Professor Derrick Pounder in 2004/05, no active poison was found in Rasputin's stomach. It could not be determined with certainty that he drowned, as the water found in his lungs is a common non-specific autopsy finding. One bullet had passed through the body, so it was impossible to tell who many people were shooting and to determine whether only one kind of revolver was used.

Pounder states that, of all the shots fired into Rasputin's body, the one which entered his forehead was instantly fatal. Neither Purishkevich nor Yusupov mention the close quarter shot to the forehead.[200] This shot also provides some intriguing evidence. In Zharov and Pounder's view, with which the Firearms Department of London's Imperial War Museum agrees, the third shot was fired from a different gun from those responsible for the other two wounds. The "size and prominence of the abraded margin" suggested a large lead non-jacketed bullet. At the time, the majority of weapons used hard metal-jacketed bullets, with Britain virtually alone in using lead unjacketed bullets in their officers' Webley revolvers.[199][201] Pounder came to the conclusion that the bullet which caused the fatal shot was a Webley .455 inch unjacketed round, the best fit with the available forensic evidence.[202] Fuhrmann and Nelipa think it is not very likely a Webley and an unjacketed bullet was used; its impact would have been different.[203]

All three sources agree that Rasputin had been systematically beaten and attacked with a bladed weapon; but, most importantly, there were discrepancies regarding the number and caliber of different handguns used. This discovery may significantly change the whole premise and account of Rasputin's death. British intelligence reports, sent between London and Petrograd in 1916, indicate that the British were not only extremely concerned about Rasputin's displacement of pro-British ministers in the Russian government but, even more importantly, his apparent insistence on withdrawing Russian troops from World War I. This withdrawal would have allowed the Germans to transfer their Eastern Front troops to the Western Front, leading to a massive outnumbering of the Allies, and threatening their defeat. Whether this was actually Rasputin's intent or whether he was simply concerned about the huge number of Russian casualties (as the Tsarina's letters indicate) is in dispute, but it is clear that the British perceived him as a real threat to the war effort.[204]

SIS

There were two officers of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) in Petrograd at the time. Witnesses stated that at the scene of the murder, the only man present with a Webley revolver was Lieutenant Oswald Rayner, a British officer attached to the SIS station in Petrograd, who had visited the Yusupov palace several times on the day of the murder. This account is further supported by an audience between the British Ambassador, Sir George Buchanan, who knew about an assassination attempt before it happened,[205] and Tsar Nicholas II, when Nicholas stated that he suspected "a young Englishman who had been a college friend of prince Felix Yusupoff, of having been concerned in Rasputin's murder ...".[206] Rayner certainly had known Yusupov at the University of Oxford. The second SIS officer in Petrograd at the time was Captain Stephen Alley, born in the Yusupov Palace in 1876. Both families had very strong ties so it is difficult to come to any conclusion about whom to hold responsible.

Confirmation that Rayner met with Yusupov (along with another officer, Captain John Scale) in the weeks leading up to the killing can be found in the diary of their chauffeur, William Compton, who recorded all visits.[207] The last entry was made on the night after the murder. Compton said that "it is a little-known fact that Rasputin was shot not by a Russian but by an Englishman" and indicated that the culprit was a lawyer from the same part of the country as Compton himself. There is little doubt that Rayner was born some ten miles from Compton's hometown. Rayner became a sollicitor at the HM Treasury.[208]

Evidence that the attempt had not gone quite according to plan is hinted at in a letter which Alley wrote to Scale eight days after the murder: "Although matters here have not proceeded entirely to plan, our objective has clearly been achieved. ... a few awkward questions have already been asked about wider involvement. Rayner is attending to loose ends and will no doubt brief you."[209]

On his return to England, Oswald Rayner not only confided to his cousin, Rose Jones, that he had been present at Rasputin's murder but also showed family members a bullet which he claimed to have acquired at the murder scene.[210] "Additionally, Oswald Rayner translated Yusupov’s first book on the murder of the peasant, sparking an interesting possibility that the pair may have shaped the story to suit their own ends."[211] Conclusive evidence is unattainable, however, as Rayner burned all his papers before he died in 1961 and his only son also died four years later.

Newspaper reporter Michael Smith wrote in his book that British Secret Intelligence Bureau head Mansfield Cumming ordered three of his agents in Russia to eliminate Rasputin in December 1916.[212] According to Sir Samuel Hoare, head of the British Intelligence Service in Russia: "If MI6 had a part in the killing of Rasputin, I would have expected to have found some trace of that".[213]

Perception

Rasputin was more multifaceted and more significant than the myths that grew up around him:

- Rasputin was neither a monk nor a saint; he never belonged to any order or religious sect;[214] he impressed many people with his knowledge and ability to explain the Bible in an uncomplicated way.[215]

- It was widely believed that Rasputin had a gift for curing bodily ailments. "In the mind of the Tsarina Rasputin was closely associated with the health of her son, and the welfare of the monarchy"[68] and eager to see him as a holy fool,[216] but his enemies saw him as a debauched religious charlatan and a lecher.

- Brian Moynahan describes him as "a complex figure, intelligent, ambitious, idle, generous to a fault, spiritual, and - utterly - amoral." He was an unusual mix, a muzhik, prophet and [at the end of his life] a party-goer.[217]

- "At first sight Rasputin looks like a symbol of decadence and obscurantism, of the complete corruption of the imperial court in which he was able to float to the top. And so he has usually been treated in the history books. The temptation to wallow in the rhetoric of the lower depths in describing him is almost irresistible. And yet the truth is somewhat simpler: Rasputin was only able to play the part he did because of the dispersal of authority which very much deepened after Stolypin's death, and because of the bewildered and unhappy isolation in which the royal couple found themselves."[218]

- "To the nobles and Nicholas’s family members, Rasputin was a dual character who could go straight from praying for the royal family to the brothel [bathhouse] down the street."[219]

- According to Eulalio he was "a charismatic and cunning man, who largely exploited his "common people" and sectarian background to become a major player in the Russian political scene."[220]

- The conspirators, who did not accept a peasant being so close to the Imperial couple, had hoped that Rasputin's removal would cause the Tsarina to retreat from political activities. They also believed that Rasputin was an agent of Germany, but he was more of a pacifist, and opposed to all wars.[122]

- In Russia, Rasputin is seen by many ordinary people and clerics, among them the late Elder Nikolay Guryanov, as a righteous man.[221] However, Alexy II of Moscow said that any attempt to make a saint of Rasputin would be "madness".[222]

- According to Dominic Lieven "more rubbish has been written on Rasputin than on any other figure in Russian history".[223]

- Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated on Sunday 28 June 1914 (New Style); two weeks later Rasputin was attacked in his home village on 29 June 1914 (Old Style), so it is not "... one of the great coincidences of history...".

In popular culture

After his death the memoirs of those who knew Rasputin became a mini-industry. The basement where he died is a tourist attraction. Numerous film and stage productions have been based on his life. He has appeared as a fictionalized version of himself in numerous other media, as well as having several beverages named after him.

- In a lost silent film, The Fall of the Romanovs (1917), Iliodor played himself.

- Rasputin and the Empress is a 1932 film about Imperial Russia. The film's inaccurate portrayal of Prince Felix and Irina Yusupov as Prince Chegodieff and Princess Natasha caused a major lawsuit against MGM.

- The disco single "Rasputin" (1978) by the German-based pop and disco group Boney M references Rasputin's alleged affair with Alexandra Fyodorovna. The tune is based on the Turkish song "Kâtibim". This song was later covered by the band Turisas.

- In the 1993 comic book, Hellboy, Rasputin aids the Nazis in opening a portal to hell.

- Rasputin was depicted as the evil villain in the 1997 American animated film Anastasia (1997 film).

- 2003 Einojuhani Rautavaara composed Rasputin, an opera in three acts

*In (2011), Josée Dayan directed a French-Russian produced a film on Rasputin for television called Raspoutine starring Gérard Depardieu in the role of Rasputin and Vladimir Mashkov as Nicholas II

- Rasputin was the subject of the BBC Radio 4 series Great Lives, first aired on 1 January 2013.[224]

- Rasputin is the subject of a musical theatre production, Ripples to Revolution, by Peter Karrie[225]

- With the aim of casting Leonardo DiCaprio as Rasputin, Warner Brothers have bought the rights to a screenplay by Jason Hall.[226]

- Saint Martyr Grigori Rasputin the website of Oleg Molenko

More items on Rasputin like bands and products that bear his name in:

Notes

- ^ Colin Wilson said in 1964 that "No figure in modern history has provoked such a mass of sensational and unreliable literature as Grigori Rasputin. More than a hundred books have been written about him, and not a single one can be accepted as a sober presentation of his personality. There is an enormous amount of material on him, and most of it is full of invention or wilful inaccuracy. Rasputin's life, then, is not 'history'; it is the clash of history with subjectivity."[3]

- ^ This discrepancy arises due to the fact that the Gregorian calendar was not introduced into Soviet Russia until 1918, see Old Style and New Style dates.

References

- ^ A. Kerensky (1965) Russia and History's turning point, p. 182.

- ^ a b Rasputin: The Mad Monk [DVD]. USA: A&E Home Video. 2005.

- ^ C. Wilson, Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs, 1964, pp. 11, 14, 16.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 147.

- ^ Fuhrmann, p. xiii

- ^ Demystifying the life of Grigory Rasputin; "Royal Russia News: Demystifying the life of Grigory Rasputin". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ^ E. Radzinsky (2000) The Rasputin File p. 25, 29.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 9.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 11–13.

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) My father.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 16.

- ^ Spiridovitch, A. (1935) Raspoutine (1863–1916), p. 15.

- ^ [1]

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 22; B. Moynahan, p. 32.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 17.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts (2005), "The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History, p. 967 [2].

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010) The Murder of Grigorii Rasputin. A Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Real Tsaritsa by Madame Lili Dehn

- ^ Amalrik, A. (1988) Biografie van de Russische monnik 1863-1916, p. 45; J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 24; B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, p. 43.

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ Iliodor (1918), p. 91

- ^ "The Life And Death Of Rasputin". Orthodoxchristianbooks.com. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ^ E. Radzinsky, p. 57.

- ^ "Nicolas' diary 1905 (in Russian)". Rus-sky.com. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 33.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 41

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 42; M. Nelipa (2010), p. 24; Iliodor, p. 112.[3].

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 149.

- ^ The Atlantic; "Memories of the Russian Court - an online book on Romanov Russia - Chapter VI". Alexanderpalace.org. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ^ A. Vyrubova (1923), Memories of the Russian Court, p. 94; R.C. Moe, p. 156.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 100-101.

- ^ G. King (1994) The Last Empress: The Life and Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress of Russia, p. 174.

- ^ B. Pares (1939), p. 138.

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) My father, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Rasputin and the Empress: Authors of the Russian Collapse by Sir Bernard Pares [4]

- ^ B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, p. 165.

- ^ "Grigory Rasputin – Russiapedia History and mythology Prominent Russians". Russiapedia.rt.com. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 21.

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 167.

- ^ My Ideas and Thoughts by G. Rasputin

- ^ Out of My Past: Memoirs of Count Kokovtsov, p. 299

- ^ Iliodor, p. 116

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) My father, p. 66.

- ^ B. Pares, p. 150; M. Nelipa, p. 75.

- ^ G. King (1994), p. 188; B. Moynahan (1997), p. 168; A. Spiridovich, p. 286; J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 92.

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) My father, p. 70.

- ^ Colin Wilson (1964) Rasputin and the fall of the Romanovs, p. 139, 147.

- ^ G.W. van der Meiden, p. 84.

- ^ B. Moynahan, p. 37, 39.

- ^ Fuhrmann (2013), p. XXVII, 20, 53-54, 80

- ^ B. Moynahan, p. 52.

- ^ Grigori Rasputin predicted the end of the world to come on August 23, 2013

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934), p. 90; B. Almasov, p. 168-172.

- ^ 'Rasputin' book at Edvard Radzinsky' home page (in Russian)

- ^ Rasputin: a false myth about the Russian sexual giant from New Petersburg newspaper Template:Ru icon

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934), p. 117.

- ^ a b A. Vyrubova (1923), Memories of the Russian Court, p. 388.

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ G. King (1994) p. 199.

- ^ B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, p. 154.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 256.

- ^ Iliodor, The Mad Monk, p. 193

- ^ B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, p. 169-170; J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 91.

- ^ O. Antrick (1938) Rasputin und die politischen Hintergründe seiner Ermordung, p. 32.

- ^ Out of My Past: Memoirs of Count Kokovtsov, p. 303

- ^ B. Pares, p. 148-149.

- ^ a b G. King (1994), p. 191.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 212.

- ^ Out of My Past: Memoirs of Count Kokovtsov, p. 418

- ^ O. Anstrick, p. 37.

- ^ D. Lieven, p. 185.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 117-118.

- ^ British newspaper archive; New York Times; J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 126.

- ^ The Lincoln Star › 6 May 1917 › Page 25

- ^ The Czar Sends His Own Physician to Attend the Court Favorite Article in the NYT 15 July 1914 [5]

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 131.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 120.

- ^ E. Radzinsky, p. 257-258.

- ^ Mon père Grigory Raspoutine. Mémoires et notes (par Marie Solovieff-Raspoutine) J. Povolozky & Cie. Paris 1923; Matrena Rasputina, Memoirs of The Daughter, Moscow 2001. ISBN 5-8159-0180-6 Template:Ru icon

- ^ a b M. Rasputin (1934) My father, p. 12.

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934), p. 88.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 85, 524.

- ^ Russiapedia

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 48.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 277.

- ^ G. King (1994), p. 192.

- ^ Fontanka 16: The Tsars' Secret Police by Charles A. Ruud, Sergei Stepanov [6]

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) My father, p. 34.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 49.

- ^ Alexanderpalace Okhrana Surveillance Report on Rasputin – from the Soviet Krasnyi Arkiv

- ^ a b Alexanderpalace

- ^ B. Pares, p. 139.

- ^ The Rasputin File by Edvard Radzinsky, p. ?; O. Figes (1996) A People's Tragedy. The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, p. 32-33.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 90-94; J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 139-141

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 348-350.

- ^ O. Anstrick, p. 35, 39; A. Vyrubova (1923), Memories of the Russian Court, p. 173.

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ Victor Alexandrov, The End of the Romanovs, trans. William Sutcliffe (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1966), 155.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 284, 305.

- ^ O. Anstrick (1938) Rasputin und die politischen Hintergründe seiner Ermordung, pp 59-60.

- ^ G.A. Hosking (1973) The Russian constitutional experiment. Government and Duma, 1907-1914, p. 205.

- ^ O. Figes (1996) A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924, p. 270.

- ^ B. Pares (1939), p. 153.

- ^ O. Figes (1996) A People's Tragedy. The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, p. 34; B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, p. 169; J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 129.

- ^ Alexanderpalace; R.C. Moe, p. 332.

- ^ G. King (1994), p. 226.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 148-149; R.C. Moe, p. 331-332.

- ^ O. Figes, A People's Tragedy: Russian Revolution, 1891-1924, p. 276.

- ^ Петербургские квартиры Распутина

- ^ J. T. Fuhrmann (2013) Rasputin: The Untold Story, p. 141.

- ^ G. King (1994) The Last Empress: The Life and Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress of Russia, p. xi.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 157.

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ A. Kerensky (1965) Russia and History's turning point, p. 160; M. Nelipa (2010), p. 163; A. Vyrubova (1923), Memories of the Russian Court, p. 289/290; R.C. Moe, p. 387.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 505. G. King (1994), p. 258; B. Pares (1939), p. 400.

- ^ THE GREAT RUSSIAN REVOLUTION by Victor Chernov ; G. Buchanan (1923) My mission to Russia and other diplomatic memories, p. 77. [7]

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 272; AN AMBASSADOR'S MEMOIRS by Maurice Paléologue. Sunday, May 30, 1915 [8].

- ^ O. Figes (1996), p. 286.

- ^ Vladimir I. Gurko (1939) "Features and Figures of the Past", p. 10. [9]

- ^ a b O. Figes (1996), p. 287.

- ^ a b Alexanderpalace; B. Pares (1939), p. 188, 222; M. Nelipa (2010) p. 83, 85.

- ^ The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents, Volume 1, p. 16 by Robert Paul Browder, Aleksandr Fyodorovich Kerensky [10]

- ^ B. Pares (1939), p. 392.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 120; O. Antrick, p. 119.

- ^ The Murder of Grigorii Rasputin; a Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire

- ^ A. Kerensky (1965) Russia and History's turning point, p. 150.

- ^ The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents, Volume 1, p. 18 by Robert Paul Browder, Aleksandr Fyodorovich Kerensky [11]

- ^ O. Figes (1997) A People's Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution, p. 278. [12]; The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 2, Imperial Russia, 1689-1917, p. 668 by Maureen Perrie, Dominic Lieven, Ronald Grigor Suny [13]

- ^ E. Radzinsky, p. 434.

- ^ The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents, Volume 1, p. 17 by Robert Paul Browder, Aleksandr Fyodorovich Kerensky [14]

- ^ Tatyana Mironova. Grigori Rasputin: Belied Life – Belied Death

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 112-115.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 130, 134.

- ^ B. Pares (1939), p. 402.

- ^ Hasegawa, T. (1981) The February Revolution: Petrograd, 1917, p. 58.

- ^ Warchron; R.C. Moe, p. 473.

- ^ http://www.questia.com/read/3552177/official-statements-of-war-aims-and-peace-proposals

- ^ Nicholas and Alexandra: The Tragic, Compelling Story of the Last Tsar and ... by Robert K. Massie [15]; Moe, p. 458.

- ^ At the court of the last tsar: the memoirs of A. A. Mossolov, head of the court chancellery, 1900-1916, p. 170-173. [16]

- ^ B. Pares, p. 395; E. Radzinsky (2010) The Rasputin File [17]; G.W. van der Meiden, p. 70.

- ^ O. Antrick, p. 79, 117.

- ^ Raymond Pearson (1964) The Russian moderates and the crisis of Tsarism 1914-1917, p. 128.

- ^ B. Pares (1939), p. 398.

- ^ B. Pares (1939), p. 428.

- ^ O. Figes (1996), p. 811.

- ^ G. Buchanan, p. 37; B. Pares (1939), p. 403.

- ^ a b Meiden, G.W. van der (1991) Raspoetin en de val van het Tsarenrijk, p. 75.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 98; O. Figes (1996) A People's Tragedy. The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, p. 290; Prins Joesoepov, (1929) De dood van Raspoetin, p. 156; Spiridovich, A. (1935) Raspoutine (1863-1916), p. 374; Meiden, G.W. van der (1991) Raspoetin en de val van het Tsarenrijk, p. 74.

- ^ The Spirit of Gregory Efimovich Rasputin-Novykh of the village of Pokrovskoe

- ^ B. Pares, p. 398; Edvard Radzinsky The Rasputin File

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 99, 399.

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) p. 109; M. Nelipa, p. 224.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 134.

- ^ Farquhar, Michael (2001). A Treasure of Royal Scandals, p. 197. Penguin Books, New York. ISBN 0-7394-2025-9; The Russian Revolution by Richard Pipes, p. 263. [18].

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) p. 12, 71, 111.

- ^ Simanotwitsch, A. (1928) Rasputin. Der allmächtige Bauer, p. 37; E. Radzinsky, p. 477.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 209-210.

- ^ Saturday 6 January 1917

- ^ To Kill Rasputin, by Andrew Cook. A review by Greg King

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 200.

- ^ Almasoff, B. (1923) p. 189, 189, 210-212; Yusupov, F. (1952) Lost Splendor, chapter XXIII The Moika basement - The night of December 29.; Spiridovich, A. (1935) Raspoutine (1863–1916), p. 383; Simanotwitsch, A. (1928) Rasputin. Der allmächtige Bauer, p. 270; Pourichkévitch, V. (1924) Comment j'ai tué Raspoutine, p. 110 [19]; E. Radzinsky, p. 458.

- ^ a b O.A. Platonov Murder

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 211.

- ^ Wikimapia

- ^ Almasov, B. (1924) Rasputin und Russland, p. 204.

- ^ The Guardian Rasputin killed by Tsar's nephew?

- ^ a b c Alexander Palace; Samuel Hoare (1930) The Fourth Seal, p. 154

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 102, 354, 529.

- ^ S. Hoare, p. 152

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 529.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 225.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 534.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 383.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 570.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 217; M. Nelipa, p. 379; Platonov, O.A. (2001) Prologue regicide.

- ^ Spiridovich, A. (1935) Raspoutine (1863-1916), p. 402; B. Moynahan, p. 245.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 221.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 391.

- ^ G. King (1994), p. 275.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 569.

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ Places connected with the murder

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) My father, p. 16; J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 222

- ^ B. Almasov, p. 214; B. Pares, p. 146.

- ^ B. Almasov, p. 193, 213.; M. Nelipa (2010), p. 467

- ^ AN AMBASSADOR'S MEMOIRS by Maurice Paléologue on Monday, January 29, 1917

- ^ O. Figes, p. 278

- ^ O. Figes, p. 380.

- ^ M. Nelipa, p. 424-425, 430, 476.

- ^ B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, p. 354-355.

- ^ Spiridovich, A. (1935) Raspoutine (1863-1916), p. 421; O. Figes, p. 291; E. Radzinsky, p. 493; O. Antrick, p. 154.

- ^ Saint Petersburg Encyclopaedia; Sergei Fomin "How they burned Him" in Russky Vestnik, May 5th, 2002; M. Nelipa (2010), p. 454, 457; R.C. Moe, p. 627.

- ^ M. Nelipa (2010), p. 2.

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 666.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 197, 200.

- ^ Google news

- ^ a b "To Kill Rasputin: The Life and Death of Grigori Rasputin" by Andrew Cook

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ Top Documentary Films

- ^ Uncovering the truth of the death of Rasputin at University of Dundee site; Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: A Deadly Game: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot, Hachette UK, 2013 p.39

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 229; M. Nelipa (2010), p. 388.

- ^ Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: A Deadly Game: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot,Hachette UK, 2013 p.29

- ^ G. Buchanan, p. 48

- ^ G. Buchanan, p. 51

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann (2013), p. 230–231

- ^ R.C. Moe, p. 653.

- ^ Education. "British spy 'fired the shot that finished off Rasputin'". Telegraph. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ^ J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 230

- ^ To Kill Rasputin, by A. Cook

- ^ How Britain's first spy chief ordered Rasputin's murder (in a way that would make every man wince), by Annabel Venning, Daily Mail, 22 July 2010.

- ^ The Guardian Spy secrets revealed in history of MI6

- ^ M. Rasputin (1934) My Father, p. 23.

- ^ Rasputin: The Untold Story by J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 28

- ^ The Rasputin File by Edvard Radzinsky, p. 243. [20]; J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 64. [21]; From Splendor to Revolution: The Romanov Women, 1847--1928 by Julia P. Gelardi [22]

- ^ B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, Preface.

- ^ G.A. Hosking (1973) The Russian constitutional experiment. Government and Duma, 1907-1914, p. 208–209.

- ^ On this day: Russia in a click, but with a wrong date. It should 12 July 1914.

- ^ Libertinage in Russian Culture and Literature: A Bio-History of Sexualities ... by Alexei Lalo, p. 89-90.[23]

- ^ Elder Nikolay Guryanov's testament for Russia (in Russian)

- ^ Orthodox Church Takes On Rasputin

- ^ Dominic Lieven (1993) Nicholas II: Twilight of the Empire, p. 273. John Murray/St Martin's Press; Ronald C. Moe, p. 6.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Great Lives, Series 29, Grigori Rasputin". Bbc.co.uk. 2013-01-04. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ^ "Rasputin, Ripples to Revolution - Home". Rasputinthemusical.weebly.com. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ^ "Leonardo di Caprio set to play Rasputin". The Guardian.

Bibliography

- Andrew Cook (2007) To Kill Rasputin: The Life and Death of Grigori Rasputin. History Press Limited.

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2013). Rasputin, the untold story (illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 314. ISBN 978-1-118-17276-6.

- Greg King (1994) The Last Empress. The Life & Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, tsarina of Russia. A Birch Lane Press Book.

- Massie, Robert K (2004) [originally in New York: Atheneum Books, 1967]. Nicholas and Alexandra: An Intimate Account of the Last of the Romanovs and the Fall of Imperial Russia (Common Reader Classic Bestseller ed.). United States: Tess Press. p. 672. ISBN 1-57912-433-X. OCLC 62357914.

- Ronald C. Moe, Prelude to the Revolution: The Murder of Rasputin (Aventine Press, 2011).

- Brian Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned. Random House.

- Radzinsky, Edvard (2000). Rasputin: The Last Word. St Leonards, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin. p. 704. ISBN 1-86508-529-4. OCLC 155418190. Originally in London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Margarita Nelipa (2010) The Murder of Grigorii Rasputin. A Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire, Gilbert's Books. ISBN 978-0-9865310-1-9.

- Bernard Pares (1939) The Fall of the Russian Monarchy. A Study of the Evidence. Jonathan Cape. London.

- Vladimir Pourichkevitch (1924) Comment j'ai tué Raspoutine. Pages de Journal. J. Povolozky & Cie. Paris

- Alexander Spiridovich (1935) Raspoutine (1863-1916). Paris, Payot.

- Frances Welch (2014) Rasputin: A Short Life. Short Books Ltd. ISBN 9781780721538

External links

- Photographs and films about Grigorii Yefimovich Rasputin

- The Alexander Palace Time Machine Bios-Rasputin – bio of Rasputin

- Russian Revolutions of 1917 (Archived 2009-10-31)

- The Murder of Rasputin

- BBC's Rasputin murder reconstruction

- RASPUTIN Grigory Efimovich in: Encyclopaedia of St Petersburg

- Grigori Efimovich Rasputin "My Ideas and Thoughts"

- Documentary: Last of the Czars (II) - The shadow of Raputin

- Rasputin the man - The reasons for his influence and its consequences. in: Felix Yusupov (1952) Lost Splendor, chapter XXI.

- Grigori Rasputin

- 1869 births

- 1916 deaths

- Rasputin family

- People from Siberia

- Russian religious figures

- Russian Orthodox Christians

- Eastern Orthodox Christians from Russia

- Christian mystics

- Faith healers

- Folk saints

- Russian folk dances

- Nicholas II of Russia

- Russian murder victims

- Assassinated Russian people

- Deaths by firearm in Russia

- People murdered in Russia